Abstract

The human pathogen Staphylococcus aureus is isolated and characterized using traditional culture and sensitivity methodologies that are slow and offer limited information on the organism. In contrast, DNA microarray technology can provide detailed, clinically relevant information on the isolate by detecting the presence or absence of a large number of virulence-associated genes simultaneously in a single assay. We have developed and validated a novel, cost-effective multiwell microarray for the identification and characterization of Staphylococcus aureus. The array comprises 84 gene targets, including species-specific, antibiotic resistance, toxin, and other virulence-associated genes, and is capable of examining 13 different isolates simultaneously, together with a reference control strain. Analysis of S. aureus isolates whose complete genome sequences have been determined (Mu50, N315, MW2, MRSA252, MSSA476) demonstrated that the array can reliably detect the combination of genes known to be present in these isolates. Characterization of a further 43 S. aureus isolates by the microarray and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis has demonstrated the ability of the array to differentiate between isolates representative of a spectrum of S. aureus types, including methicillin-susceptible, methicillin-resistant, community-acquired, and vancomycin-resistant S. aureus, and to simultaneously detect clinically relevant virulence determinants.

Staphylococcus aureus is a common human pathogen responsible for a plethora of infections, from superficial skin infections to life-threatening diseases such as endocarditis, sepsis, and pneumonia. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the hospital setting. The emerging threats of community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA) highlight the importance of rapid detection of such infections.

Most diagnostic microbiology laboratories continue to identify S. aureus using traditional culture and susceptibility methods that are slow (48 to 72 h) and provide only limited information. Molecular assays based on PCR have been reported for the detection of MRSA (4, 6, 7, 9, 10, 30), the identification of staphylococcal species (17, 20, 21), or the identification of specific virulence genes (5, 11, 14, 15, 18, 19, 22, 24, 26, 33). DNA microarrays can identify, subtype, and detect acquired antibiotic resistance determinants simultaneously (1, 23, 32, 35); however, their clinical value has been limited by a complicated methodology that is unsuitable for routine use in diagnostic microbiology laboratories.

We have developed an oligonucleotide-based microarray (designated VirEp, for virulence and epidemiology microarray) incorporating 84 clinically relevant gene targets for the characterization and molecular typing of clinical isolates of S. aureus in an economical, multiwell format enabling 13 S. aureus isolates to be analyzed simultaneously.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates and culture conditions.

The isolates used in this study (Table 1) were grown at 37°C for 16 h on brain heart infusion agar, except for the VRSA isolates, for which 6 μg/ml of vancomycin was added to the brain heart infusion agar.

TABLE 1.

S. aureus isolates used in this study

| Isolate | Sourcea | Originb | Site of isolation | Descriptionc | Disease association |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRSA252d,e | NARSA | United Kingdom | Blood | Sequenced epidemic MRSA | Septicemia |

| MSSA476d,e | NARSA | United Kingdom | N/K | Sequenced CA-MSSA | Osteomyelitis |

| Mu50d,e | NARSA | Japan | Wound/skin | GISA | Wound infection |

| MW2d,e | NARSA | North Dakota | Blood | Sequenced CA-MRSA | Septic arthritis |

| N315d,e | NARSA | Japan | Pharyngeal smear | Sequenced MRSA | N/K |

| NRS4d,e | NARSA | New Jersey | Blood | GISA | Peritonitis |

| NRS77d,e | NARSA | United Kingdom | N/K | MSSA | N/K |

| NRS111d,e | NARSA | United States | N/K | TSST-1-positive MSSA | N/K |

| NRS157d,e | NARSA | France | N/K | CA-MSSA | Necrotizing pneumonia |

| NRS176d,e | NARSA | France | Abscess | TSST-1-positive MSSA | Nonmenstrual TSS |

| NRS179d,e | NARSA | France | Blood | TSST-1-positive MSSA | Scarlet fever |

| NRS182d,e | NARSA | France | Blood | MSSA | Endocarditis |

| NRS188d,e | NARSA | France | Pus | MSSA | Osteomyelitis |

| NRS192d,e | NARSA | Minnesota | Hip/blood | CA-MRSA | Septic arthritis, pneumonia |

| NRS194d,e | NARSA | North Dakota | Pleural fluid | CA-MRSA | Necrotizing pneumonia |

| NRS229d,e | NARSA | France | Blood | CA-MSSA | Necrotizing pneumonia |

| NRS231d,e | NARSA | France | Bone/joint | MSSA | Arthritis |

| NRS233d,e | NARSA | France | Wound/skin | MSSA | Bulbous impetigo |

| NRS248d,e | NARSA | Minnesota | Bronchoalveolar fluid | CA-MRSA | Necrotizing pneumonia |

| NRS249d,e | NARSA | France | Blood | MRSA | Endocarditis |

| NRS265d,e | NARSA | Switzerland | Wound/skin | MRSA | Bulbous impetigo |

| NRS272d,e | NARSA | Belgium | Sputum | GISA | Pulmonary exacerbation |

| NRS283d,e | NARSA | United Kingdom | Blood | GISA | Endocarditis |

| VRS1d,e | NARSA | Michigan | Catheter exit site | VRSA | Wound infection |

| VRS2d,e | NARSA | Pennsylvania | Wound/skin | VRSA | Wound infection |

| VRS3d,e | NARSA | New York | Urine | VRSA | Urinary tract infection |

| CC7d,e | QMC | Nottingham, United Kingdom | Nose | MRSA | Carriage |

| CC356d,e | QMC | Nottingham, United Kingdom | Nose | MRSA | Carriage |

| RSS035d,e | QMC | Nottingham, United Kingdom | Vagina | TSST-1-positive MSSA | TSS |

| RSS092d,e | QMC | Nottingham, United Kingdom | Blood | MSSA | Septic arthritis |

| RSS136d,e | QMC | Nottingham, United Kingdom | Blood | MRSA | Endocarditis |

| RSS161d,e | QMC | Nottingham, United Kingdom | Blood | MSSA | Septic arthritis |

| RSS199d | QMC | Nottingham, United Kingdom | Blood | MRSA | Endocarditis |

| RSS230d,e | QMC | Nottingham, United Kingdom | Blood | MSSA | Osteomyelitis |

| RSS242d,e | QMC | Nottingham, United Kingdom | Blood | MSSA | Endocarditis |

| RSS254d,e | QMC | Nottingham, United Kingdom | Wound | EMRSA-15 variant B1 (PFGE) | N/K |

| RSS255d,e | QMC | Nottingham, United Kingdom | Sputum | EMRSA-15 variant B5 (PFGE) | N/K |

| RSS256d,e | QMC | United Kingdom | N/K | EMRSA-15 UK | N/K |

| RSS257d,e | QMC | United Kingdom | N/K | EMRSA-16 UK | N/K |

| RSS258d | QMC | Nottingham, United Kingdom | Sputum | EMRSA-15 new variant (PFGE) | N/K |

| RSS289d,e | QMC | Nottingham, United Kingdom | Wound | CA-MSSA | N/K |

| RSS291d,e | QMC | Nottingham, United Kingdom | Wound | MRSA | Destruction of skin grafts |

| MSSA32130d,e | J. E. Corkill | Liverpool, United Kingdom | N/K | Pre-MRSA | N/K |

| MRSA32344d,e | J. E. Corkill | Liverpool, United Kingdom | N/K | MRSA corresponding to pre- MRSA | N/K |

| ND96d | N. Day, S. Peacock | United Kingdom | N/K | MRSA | Invasive disease |

| ND3026d | N. Day, S. Peacock | United Kingdom | N/K | Carriage MRSA | Carriage |

| RSSmec1 | D. Morrison | N/K | N/K | MRSA containing SCCmec type I | N/K |

| RSSmec2 | D. Morrison | N/K | N/K | MRSA containing SCCmec type II | N/K |

| RSSmec3 | D. Morrison | N/K | N/K | MRSA containing SCCmec type III | N/K |

| RSSmec4 | D. Morrison | N/K | N/K | MRSA containing SCCmec type IV | N/K |

| WIS | T. Ito | N/K | N/K | MRSA containing SCCmec V | N/K |

| H034820381d | A. Kearns | United Kingdom | N/K | S. aureus outbreak isolate | N/K |

| H040380042d | A. Kearns | United Kingdom | N/K | S. aureus outbreak isolate | N/K |

| H040380045d | A. Kearns | United Kingdom | N/K | S. aureus outbreak isolate | N/K |

| H040680209d | A. Kearns | United Kingdom | N/K | S. aureus outbreak isolate | N/K |

| H040680232d | A. Kearns | United Kingdom | N/K | S. aureus outbreak isolate | N/K |

| H041000045d | A. Kearns | United Kingdom | N/K | S. aureus outbreak isolate | N/K |

| H042340013d | A. Kearns | United Kingdom | N/K | S. aureus outbreak isolate | N/K |

| H042340015d | A. Kearns | United Kingdom | N/K | S. aureus outbreak isolate | N/K |

| H055000318d | A. Kearns | United Kingdom | N/K | S. aureus outbreak isolate | N/K |

| H055000319d | A. Kearns | United Kingdom | N/K | S. aureus outbreak isolate | N/K |

| H055000320d | A. Kearns | United Kingdom | N/K | S. aureus outbreak isolate | N/K |

| H055180446d | A. Kearns | United Kingdom | N/K | S. aureus outbreak isolate | N/K |

| H060620441d | A. Kearns | United Kingdom | N/K | S. aureus outbreak isolate | N/K |

| H060620443d | A. Kearns | United Kingdom | N/K | S. aureus outbreak isolate | N/K |

| H060140520d | A. Kearns | United Kingdom | N/K | S. aureus outbreak isolate | N/K |

| H060140521d | A. Kearns | United Kingdom | N/K | S. aureus outbreak isolate | N/K |

| H060140523d | A. Kearns | United Kingdom | N/K | S. aureus outbreak isolate | N/K |

| H060480457d | A. Kearns | United Kingdom | N/K | S. aureus outbreak isolate | N/K |

NARSA, Network on Antimicrobial Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus, Focus Technologies Inc., Herndon, VA; QMC, Diagnostic Microbiology Laboratory, Queens Medical Centre, Nottingham, United Kingdom. The affiliations of individuals who supplied isolates are as follows: John E. Corkill, Department of Medical Microbiology, Royal Liverpool University Hospital, Liverpool, United Kingdom; Nick Day and Sharon Peacock, Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand; Donald Morrison, Scottish MRSA Reference Laboratory, Department of Microbiology, Stobhill Hospital, Glasgow, United Kingdom; Teruyo Ito, Department of Bacteriology, Juntendo University, Tokyo, Japan; and Angela M. Kearns, Staphylococcus Reference Laboratory, Centre for Infections, Health Protection Agency, London, United Kingdom.

N/K, not known.

TSST-1, toxic shock syndrome toxin 1.

Examined using the complete S. aureus microarray.

Examined by microarray and PFGE.

Oligonucleotide probe design and synthesis.

Oligonucleotide probes were designed using OligoArray 2.0 software (28) and were synthesized at a 10-nmol scale with amino C6 modification (Operon Biotechnologies). Three 45- to 46-mer oligonucleotides with calculated melting temperatures of 68 to 72°C and minimal internal structure were selected for each gene target (see Appendix S1 in the supplemental material). Where this was not possible, shorter or longer oligonucleotides were used.

Slide printing.

Oligonucleotides were printed onto amine silane-coated UltraGAPS slides (Corning B.V. Life Sciences) at a concentration of 20 μM in spotting buffer (3 × SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate], 1.5 M betaine) along with Universal ScoreCard controls (GE Healthcare UK Ltd.) and appropriate positive and negative controls (see the supplemental material). Fourteen replicates of the array were printed on each microarray slide using a QArray Lite robotic arrayer (Genetix Ltd.).

DNA extraction and labeling.

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from S. aureus cultures using the DNeasy tissue kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions with the addition of 5 μl of lysostaphin (0.5 mg/ml) and 2 μl of RNase A (100 mg/ml) to the lysis buffer. The concentration of gDNA was determined using a Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Nanodrop Technologies Inc.). gDNA and spike-in Universal controls (for details, see Appendix S3 in the supplemental material) were labeled with Cy3-dCTP using a protocol based on that described by Pearson et al. (27).

Hybridization.

Microarray slides were incubated in prehybridization solution (5× SSC, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin) for 60 min at 60°C, washed twice in 0.1× SSC for 5 min and once in purified water for 30 s at room temperature, and then dried by centrifugation. Prior to hybridization, ProPlate superstructures (Stratech Scientific Ltd.) were attached to the slides to create a multiwell format. Forty picomoles of Cy3-labeled gDNA in 50 μl of hybridization solution (5× SSC, 0.1% SDS, and 0.1 mg/ml herring sperm DNA) was denatured at 95°C for 5 min. Hybridization mixtures were then added to individual wells on the slide before wells were sealed. Slides were hybridized at 60°C for 16 h in the dark with gentle agitation before being washed in 2× SSC-0.1% SDS at 42°C once to remove the superstructure and once for 5 min. Slides were then washed twice for 5 min in 0.1× SSC-0.1% SDS, five times for 1 min in 0.1× SSC, and once for 10 s in 0.01× SSC. Arrays were dried by centrifugation at 1,600 × g for 2 min.

Data analysis.

Hybridized slides were scanned with an Axon 4000B slide scanner (Molecular Devices Corporation) using a resolution of 10 μm, and images were analyzed with GenePix Pro 6.0 software. Spots with a signal-to-noise ratio of ≥1 and a total median fluorescence at 532 nm of >1,000 after subtraction of the background fluorescence were classified as positive. For a gene target to be considered present, at least two-thirds of the spots corresponding to that gene target had to be positive. Microarray experiments were MIAME (minimum information about a microarray experiment) compliant, and experimental data were deposited in the ArrayExpress repository (2).

PFGE.

S. aureus chromosomal SmaI digests were prepared with the GenePath group 1 reagent kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories), and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) patterns were obtained with a contour-clamped homogeneous electric field apparatus (Bio-Rad) as described previously (13). PFGE images were analyzed with BioNumerics 2.0 software (Applied Maths). Dendrograms were generated using the Dice coefficient and the unweighted-pair group method using average linkages (UPGMA) with 1% tolerance and 0.5% optimization. A similarity cutoff of 80% and a difference of ≤6 bands were used to define clusters (29, 31). The presence and absence of genes determined by microarray analysis were recorded in a binary format and processed using Bionumerics 2.0 software, and the results were presented as a dendrogram.

Statistical analysis.

The reproducibility of microarray data was examined by calculating the coefficient of variation, which is the standard deviation divided by the normalized mean for replicates hybridized to different microarrays. The discriminatory power of the VirEp (virulence and epidemiology) microarray as a typing method was determined by calculating Simpson's index of diversity (8).

RESULTS

Validation of the complete multiwell format S. aureus oligonucleotide microarray by analysis of sequenced S. aureus isolates.

An initial list of 89 gene targets, including acquired antibiotic resistance determinants, toxins, adhesins, proteases, and other virulence genes, was selected on the basis of the significance of these genes in clinical disease and epidemiology. Four replicates of S. aureus isolates MW2, N315, MRSA252, MSSA476, and Mu50 (Table 1) were hybridized to UltraGAPS microarray slides printed with the VirEp microarray. Oligonucleotides for 84/89 genes examined generated the expected results compared to sequencing data. Five gene targets (sea, seg, sep, edin-B, and sdrD) gave discrepant results and were discarded. The specificity of oligonucleotides for staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) types I to V were confirmed by hybridizing gDNA from isolates containing each SCCmec element to the VirEp microarray (Table 1). The experimental coefficient of variation for the VirEp microarray was found to be 0.14 (14%), indicating that the data generated by the VirEp microarray are reproducible.

Application of the VirEp microarray to the identification and characterization of clinical isolates of S. aureus.

Labeled DNAs from a collection of 64 clinical isolates of S. aureus were hybridized to the VirEp microarray with the remaining 84 gene targets (Table 1). All isolates were correctly identified as S. aureus based on the presence of cap, coa, cpn60, femA, nuc, and tpi genes. Ten of ten (100%) isolates were correctly identified as MSSA (Table 2), and 30 of 38 (78.9%) isolates were correctly identified as MRSA (Table 2). However, false-negative results for the mecA gene were obtained for eight MRSA isolates from the United Kingdom. Six of the eight isolates were confirmed to possess the mecA gene by PCR. We assume that isolates RSS257 and RSS258, which were mecA negative by PCR, had lost their mec element upon storage at −80°C, which has been reported to be common among MRSA isolates (34). All four CA-MRSA isolates and all three Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL)-positive MSSA isolates were correctly identified by the microarray, as were each of six tst-positive MSSA isolates and each of three VRSA isolates tested.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of laboratory and VirEp microarray characterization for diagnosis of 64 clinical isolates of S. aureus

| Isolate identificationa | No. of isolates | No. (%) correctly assigned by ViREp microarray |

|---|---|---|

| MRSA (mecA positive) | 38 | 30 (78.9) |

| MSSA (mecA negative) | 10 | 10 (100) |

| tst+ | 6 | 6 (100) |

| vanA+ | 3 | 3 (100) |

| PVL+ | 7 | 7 (100) |

Determined using standard phenotypic and genotypic techniques in the laboratories where the isolates were collected.

Analysis of microarray results revealed that 36/84 gene targets were present in all 64 isolates analyzed while 12 gene targets were absent in all isolates examined (see Appendix S2 in the supplemental material). The conserved genes included the identification genes (11%), genes encoding adhesins (25%), proteases (22%), and toxins (16.5%), acquired antibiotic resistance determinants (16.5%), and molecular typing genes (9%). Additional genes associated with adherence, antibiotic resistance, gene regulation, or production of extracellular virulence factors were found in >96% of isolates examined (aapA, etc, hla, norA, sarA, spa). Of the 12 genes determined to be absent in all isolates tested, 42% encoded antibiotic resistance genes, 33% encoded SCCmec type specific genes, 17% encoded toxin genes, and 8% encoded biofilm-related genes. Eight additional genes representing antibiotic resistance determinants (ermB, msrB, smr, tet, tetM, and vanA [identified only in the known VRSA isolates]), SCCmec type I, and enterotoxin B were identified in <10% of the isolates studied.

Among the toxin genes, those encoding two exfoliative toxins (eta and etc), alpha-hemolysin (hla), beta-toxin (hlb), delta-toxin (hld), and gamma-hemolysin (hlgA, hlgB, hlgC) were found to be present in almost all of the isolates examined. The leukocidin encoded by lukD and lukE was present in 45.3% of isolates, and PVL, encoded by the lukS and lukF genes, was identified in 10.9% of isolates. Each enterotoxin gene included on the microarray was identified in 6.3% to 67.2% of the isolates examined.

The frequency of antibiotic resistance genes in the isolates studied differed greatly. Genes involved in trimethoprim resistance (dfrA and dfrB), penicillin resistance (fmt), sulfonamide resistance (folP), streptogramin A resistance (lsa, vga), and macrolide resistance (msrA) were identified in all isolates examined. Some antibiotic resistance genes (ereA, ereB, ermC, vat, and vgb) were absent from our study isolates, whereas others (e.g., blaZ) were found in the majority of isolates examined (87.5%). Of the three genes encoding components of multidrug efflux pumps screened, norA was identified in 98.4% of the isolates examined. In contrast, qacA and qacB were found in only 11%, and smr in only <2%, of the isolates. Although we have included a number of acquired antibiotic resistance genes among the gene targets used, we have not attempted at this stage to use them as predictors of antibiotic susceptibility, because considerable further work is required to confirm that the presence of a resistance gene is correlated with phenotypic resistance in S. aureus isolates.

Nine of eleven adhesins included on the microarray were identified in the study isolates. In addition, spa, encoding protein A, was found in 98.4% of isolates, and cna, encoding a collagen adhesin protein, was found in 75% of isolates. All six proteases included on the microarray were present in all study isolates. Of the three gene targets involved in biofilm formation, one (icaA) was present in all isolates, one (aapA) was present in 98.4% of isolates, and one (bap) was absent from the study isolates. The three genes linked to capsular polysaccharide synthesis (cap1A, cap5A, and cap8A) were identified in all the study isolates. The virulence gene regulator sarA was identified in 63 of 64 (98.4%) isolates.

Among the MRSA isolates examined, there were a number of discrepancies with the SCCmec types identified by the VirEp microarray. First, 19 of 38 MRSA isolates failed to hybridize with any of the SCCmec oligonucleotides included on the microarray. Second, for three isolates, oligonucleotides specific for both SCCmec types II and IVc were identified as positive (see Appendix S2 in the supplemental material). Third, five isolates determined to be mecA negative generated positive results for SCCmec type IVc. Finally, isolate MRSA32344, which was identified as possessing SCCmec type I (3), produced a positive result with oligonucleotides specific for SCCmec type IVa. The corresponding pre-MRSA isolate MSSA32130 was correctly identified as mecA negative, but the SCCmec element was not detected.

Analysis of the population structure of clinical S. aureus isolates using PFGE and the VirEp microarray.

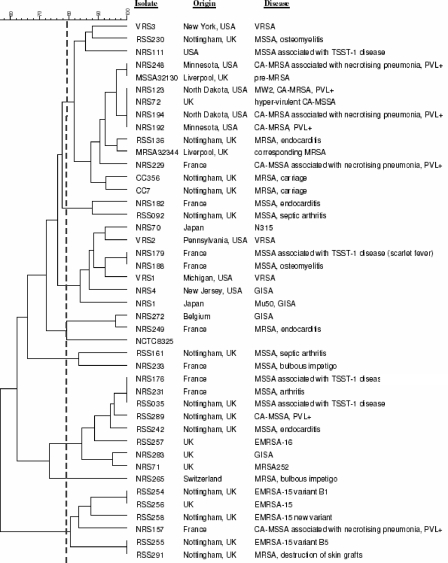

All replicates of the internal-control S. aureus isolate (NCTC8325) included in the PFGE analysis produced identical restriction fragment profiles clustering at 100% similarity, demonstrating the reproducibility of the method. The 43 test isolates generated 34 PFGE profiles according to the criteria of Tenover et al. (31) and were separated into seven clusters containing 41 out of 43 isolates (Fig. 1). Control isolate NCTC8325 and test isolate NRS265 were the only isolates found to be outliers. Cluster 1 contained 14 isolates (33%) from the United Kingdom, the United States, and France associated with a variety of diseases and included VRSA, MRSA, MSSA, CA-MRSA, and PVL-positive MSSA. Cluster 2 contained two isolates (5%): one from Nottingham, United Kingdom, associated with septic arthritis and one from France linked to endocarditis. Cluster 3 contained seven isolates (16%) from France, Japan, and the United States that were associated with different disease outcomes and included VRSA, glycopeptide-intermediate S. aureus (GISA), and MSSA. Cluster 4 consisted of two isolates (5%), one from France (MRSA) and one from Belgium (GISA). Cluster 5 was also made up of two isolates (5%), one from France and one from Nottingham, both MSSA. Cluster 6 contained eight isolates (19%) from France and the United Kingdom and included two epidemic MRSA-16 (EMRSA-16) isolates, as well as PVL-positive MSSA and MSSA isolates. Cluster 7 contained five EMRSA-15 isolates from the United Kingdom and one PVL-positive MSSA isolate from France.

FIG. 1.

Dendrogram of 43 S. aureus isolates examined by PFGE, produced with Bionumerics (version 2.0) software using the Dice coefficient and UPGMA. Isolates were clustered using the criteria of Tenover et al., where 80% similarity is the cutoff for differentiating closely related isolates (31). Clusters 1 through 7 are shown.

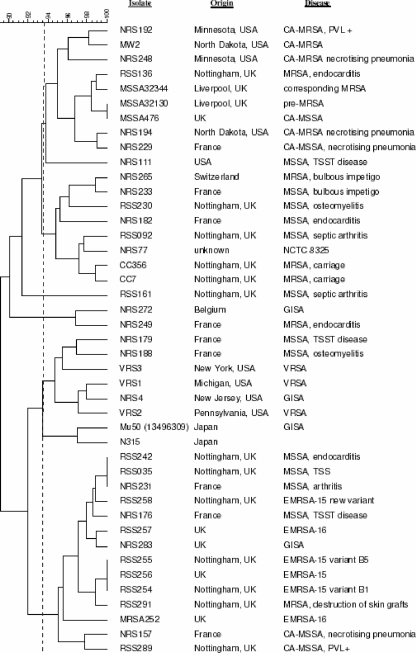

Replicates of sequenced isolates (Mu50, N315, MW2, MRSA252, and MSSA476) clustered together at 100% similarity when analyzed by the VirEp microarray, demonstrating the reproducibility of the assay. As expected, the closely related isolates Mu50 and N315, as well as isolates MW2 and MSSA476, were found to group together (16). The population structure of the 43 S. aureus clinical isolates as determined by the VirEp microarray is shown in Fig. 2. The similarity cutoff for distinguishing genotypes using the VirEp microarray (93.5%) was established by determining the percentage of similarity that grouped the sequenced S. aureus isolates correctly, as elucidated by PFGE (Fig. 2). Genotype A contained 10 isolates (23%), mainly CA-MRSA and MSSA from the United Kingdom, the United States, and France. Genotype B comprised eight MRSA and MSSA isolates (19%) from Nottingham, France, and Switzerland. Genotype C was composed of two isolates (5%), a GISA isolate from Belgium and a MRSA isolate from France. Genotype D contained eight isolates (19%), including all three VRSA, GISA, and MSSA isolates from the United States, France, and Japan. Finally, genotype E contained 14 isolates (33%) from the United Kingdom and France, including both EMRSA-15 and -16 isolates, PVL-positive MSSA, and MSSA.

FIG. 2.

Dendrogram of 43 clinical S. aureus isolates examined by the VirEp microarray, produced with Bionumerics (version 2.0) software using the Dice coefficient and UPGMA. A cutoff value of 93.5% was used to distinguish genotypes. Genotypes A through E were distinguished.

Analysis of 18 S. aureus outbreak isolates (Table 1) alone, using an arbitrary cutoff of 96% similarity, indicated that the isolates fall into two genotypes with one outlier. Comparison of microarray and PFGE results for these isolates revealed that 17 of the 18 isolates examined grouped in agreement (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Comparison of PFGE and VirEp microarray results for 18 S. aureus outbreak isolates

| Isolate | Result by:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| HPA PFGE (cluster)a | ViREp microarray (genotype)b | |

| H034820381 | 1 | E2 |

| H040380042 | 1 | E2 |

| H040380045 | 1 | E2 |

| H040680209 | 1 | E2 |

| H040680232 | 1 | E2 |

| H041000045 | 1 | E2 |

| H042340013 | 1 | E2 |

| H042340015 | 1 | E2 |

| H055000318 | 2 | E1 |

| H055000319 | 2 | E1 |

| H055000320 | 2 | E1 |

| H055180446 | 2 | E1 |

| H060620441 | 2 | E1 |

| H060620443 | 2 | E1 |

| H060140520 | 2 | E1 |

| H060140521 | 2 | Outlier |

| H060140523 | 2 | E1 |

| H060480457 | 2 | E1 |

Standard PFGE methodology was used at the Staphylococcus Reference Laboratory, Health Protection Agency (HPA), London, United Kingdom. Clusters were defined using the criteria of Tenover et al. (31).

Genotypes were differentiated using a 96% similarity cutoff.

DISCUSSION

The VirEp microarray described in this paper represents a new tool for the identification and characterization of S. aureus isolates. The benefit of the VirEp microarray for S. aureus lies in its ability to simultaneously identify numerous virulence genes while avoiding the complexities of high-density microarray analysis. The VirEp microarray successfully identified all PVL-positive isolates, all tst-positive isolates, and all VRSA isolates (Table 2), demonstrating that these clinically relevant S. aureus virulence genes can be detected by this assay. This contrasts with the limited number of genes that can be detected by PCR-based assays. While the presence of such genes does not necessarily equate with expression of the protein product, it does give a good indication to the clinician of the pathogenic potential of the isolate, which can be used to guide appropriate antimicrobial chemotherapy and infection control measures.

Furthermore, the fact that six of the eight MRSA isolates from the United Kingdom failed to hybridize to the mecA probes on the VirEp microarray yet contained the mecA gene by PCR indicated that the DNA sequences of mecA in the regions corresponding to the three probes are not conserved among all MRSA isolates. This suggests that for some genes, including mecA, sequence variation may be much greater in the wider population than among the few S. aureus isolates that have been sequenced to date. As a consequence, it is clear that further oligonucleotides are required to increase the robustness of mecA detection, a problem that is being encountered with all rapid MRSA detection systems.

The dendrogram generated from the VirEp microarray results illustrates that in general, the grouping of isolates was highly congruent with that observed with PFGE (Fig. 1 and 2). However, all three VRSA isolates were assigned to the same genotype as the EMRSA-15 and -16 isolates (Fig. 1 and 2). It is noteworthy that the percentage of similarity required to differentiate the sequenced S. aureus isolates by using the microarray results is 93.5%, whereas for PFGE it is 80% (31). This indicates that the microarray analysis provides slightly less discrimination than PFGE, probably due to the limited number of gene targets included in the microarray. This was confirmed when values for Simpson's index of diversity were calculated for the VirEp microarray and PFGE (0.771 versus 0.811). Unlike PFGE, however, the microarray provides biologically meaningful data in addition to the typing data. When isolates from two epidemiologically distinct outbreaks were examined by the VirEp microarray and PFGE, only a single incongruent isolate was found. The differences observed with this isolate were due to a difference in gene content (lukD positive, sem negative) (see Appendix S2 in the supplemental material) that could not be detected by PFGE. There were three differences in gene content between genotypes E1 and E2. Genotype E1 lacked the ermA, mupA, and tst genes, whereas genotype E2 possessed these genes (see Appendix S2 in the supplemental material). These data provide evidence that the VirEp microarray may be capable of distinguishing S. aureus isolates from different outbreaks. The VirEp microarray could be refined by the inclusion of additional selected targets that could improve the discriminatory power of the microarray. A recent study has demonstrated the potentially superior resolving power of microarrays compared to PFGE and multilocus sequence typing for typing of CA-MRSA isolates (12).

We anticipate that the VirEp assay could be used after presumptive staphylococci (gram-positive cocci in clusters) have been observed in a positive blood culture and species identification has been confirmed by an alternative methodology, such as a rapid PCR-based assay or fluorescence in situ hybridization with peptide nucleic acid probes (25). The inclusion in the array of oligonucleotides to detect coagulase-negative staphylococci would indicate if the blood culture was a mixture of S. aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci. Our current development work has been successful in reducing the time taken to perform the VirEp assay to <24 h.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Ph.D. studentship support of R.P.S. by the Medical Research Council, United Kingdom, and the University of Nottingham is gratefully acknowledged.

We thank Paddy Tighe, University of Nottingham, for helpful discussions concerning microarray technology and Katrina Levi, Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust, for assistance with PFGE and BioNumerics software. Nick Day, Angela Kearns, Sharon Peacock, Donald Morrison, John Corkill, Teruyo Ito, and the Network on Antimicrobial Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus (NARSA) are thanked for the provision of S. aureus clinical isolates.

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 February 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jcm.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anthony, R. M., A. R. Schuitema, L. Oskam, and P. R. Klatser. 2005. Direct detection of Staphylococcus aureus mRNA using a flow through microarray. J. Microbiol. Methods 6047-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brazma, A., P. Hingamp, J. Quackenbush, G. Sherlock, P. Spellman, C. Stoeckert, J. Aach, W. Ansorge, C. A. Ball, H. C. Causton, T. Gaasterland, P. Glenisson, F. C. Holstege, I. F. Kim, V. Markowitz, J. C. Matese, H. Parkinson, A. Robinson, U. Sarkans, S. Schulze-Kremer, J. Stewart, R. Taylor, J. Vilo, and M. Vingron. 2001. Minimum information about a microarray experiment (MIAME)—toward standards for microarray data. Nat. Genet. 29365-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corkill, J. E., J. J. Anson, P. Griffiths, and C. A. Hart. 2004. Detection of elements of the staphylococcal cassette chromosome (SCC) in a methicillin-susceptible (mecA gene negative) homologue of a fucidin-resistant MRSA. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 54229-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fang, H., and G. Hedin. 2003. Rapid screening and identification of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from clinical samples by selective-broth and real-time PCR assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 412894-2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Francois, P., G. Renzi, D. Pittet, M. Bento, D. Lew, S. Harbarth, P. Vaudaux, and J. Schrenzel. 2004. A novel multiplex real-time PCR assay for rapid typing of major staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec elements. J. Clin. Microbiol. 423309-3312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grisold, A. J., E. Leitner, G. Muhlbauer, E. Marth, and H. H. Kessler. 2002. Detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and simultaneous confirmation by automated nucleic acid extraction and real-time PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 402392-2397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huletsky, A., R. Giroux, V. Rossbach, M. Gagnon, M. Vaillancourt, M. Bernier, F. Gagnon, K. Truchon, M. Bastien, F. J. Picard, A. van Belkum, M. Ouellette, P. H. Roy, and M. G. Bergeron. 2004. New real-time PCR assay for rapid detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus directly from specimens containing a mixture of staphylococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 421875-1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunter, P. R., and M. A. Gaston. 1988. Numerical index of the discriminatory ability of typing systems: an application of Simpson's index of diversity. J. Clin. Microbiol. 262465-2466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaffe, R. I., J. D. Lane, S. V. Albury, and D. M. Niemeyer. 2000. Rapid extraction from and direct identification in clinical samples of methicillin-resistant staphylococci using the PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 383407-3412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jonas, D., M. Speck, F. D. Daschner, and H. Grundmann. 2002. Rapid PCR-based identification of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from screening swabs. J. Clin. Microbiol. 401821-1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klotz, M., S. Opper, K. Heeg, and S. Zimmermann. 2003. Detection of Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxins A to D by real-time fluorescence PCR assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 414683-4687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koessler, T., P. Francois, Y. Charbonnier, A. Huyghe, M. Bento, S. Dharan, G. Renzi, D. Lew, S. Harbarth, D. Pittet, and J. Schrenzel. 2006. Use of oligoarrays for characterization of community-onset methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 441040-1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumari, D. N., V. Keer, P. M. Hawkey, P. Parnell, N. Joseph, J. F. Richardson, and B. Cookson. 1997. Comparison and application of ribosome spacer DNA amplicon polymorphisms and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis for differentiation of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35881-885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lapierre, P., A. Huletsky, V. Fortin, F. J. Picard, P. H. Roy, M. Ouellette, and M. G. Bergeron. 2003. Real-time PCR assay for detection of fluoroquinolone resistance associated with grlA mutations in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 413246-3251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Letertre, C., S. Perelle, F. Dilasser, and P. Fach. 2003. Detection and genotyping by real-time PCR of the staphylococcal enterotoxin genes sea to sej. Mol. Cell. Probes 17139-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindsay, J. A., and M. T. Holden. 2004. Staphylococcus aureus: superbug, super genome? Trends Microbiol. 12378-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Louie, L., J. Goodfellow, P. Mathieu, A. Glatt, M. Louie, and A. E. Simor. 2002. Rapid detection of methicillin-resistant staphylococci from blood culture bottles by using a multiplex PCR assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 402786-2790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Løvseth, A., S. Loncarevic, and K. G. Berdal. 2004. Modified multiplex PCR method for detection of pyrogenic exotoxin genes in staphylococcal isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 423869-3872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martineau, F., F. J. Picard, L. Grenier, P. H. Roy, M. Ouellette, and M. G. Bergeron. 2000. Multiplex PCR assays for the detection of clinically relevant antibiotic resistance genes in staphylococci isolated from patients infected after cardiac surgery. The ESPRIT Trial. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 46527-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martineau, F., F. J. Picard, D. Ke, S. Paradis, P. H. Roy, M. Ouellette, and M. G. Bergeron. 2001. Development of a PCR assay for identification of staphylococci at genus and species levels. J. Clin. Microbiol. 392541-2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mason, W. J., J. S. Blevins, K. Beenken, N. Wibowo, N. Ojha, and M. S. Smeltzer. 2001. Multiplex PCR protocol for the diagnosis of staphylococcal infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 393332-3338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monday, S. R., and G. A. Bohach. 1999. Use of multiplex PCR to detect classical and newly described pyrogenic toxin genes in staphylococcal isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 373411-3414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monecke, S., and R. Ehricht. 2005. Rapid genotyping of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolates using miniaturised oligonucleotide arrays. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 11825-833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oliveira, D. C., and H. de Lencastre. 2002. Multiplex PCR strategy for rapid identification of structural types and variants of the mec element in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 462155-2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oliveira, K., G. W. Procop, D. Wilson, J. Coull, and H. Stender. 2002. Rapid identification of Staphylococcus aureus directly from blood cultures by fluorescence in situ hybridization with peptide nucleic acid probes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40247-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palladino, S., I. D. Kay, J. P. Flexman, I. Boehm, A. M. Costa, E. J. Lambert, and K. J. Christiansen. 2003. Rapid detection of vanA and vanB genes directly from clinical specimens and enrichment broths by real-time multiplex PCR assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 412483-2486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pearson, B. M., C. Pin, J. Wright, K. I'Anson, T. Humphrey, and J. M. Wells. 2003. Comparative genome analysis of Campylobacter jejuni using whole genome DNA microarrays. FEBS Lett. 554224-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rouillard, J. M., C. J. Herbert, and M. Zuker. 2002. OligoArray: genome-scale oligonucleotide design for microarrays. Bioinformatics 18486-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Struelens, M. J., A. Deplano, C. Godard, N. Maes, and E. Serruys. 1992. Epidemiologic typing and delineation of genetic relatedness of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by macrorestriction analysis of genomic DNA by using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 302599-2605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan, T. Y., S. Corden, R. Barnes, and B. Cookson. 2001. Rapid identification of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from positive blood cultures by real-time fluorescence PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 394529-4531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tenover, F. C., R. D. Arbeit, R. V. Goering, P. A. Mickelsen, B. E. Murray, D. H. Persing, and B. Swaminathan. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 332233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trad, S., J. Allignet, L. Frangeul, M. Davi, M. Vergassola, E. Couve, A. Morvan, A. Kechrid, C. Buchrieser, P. Glaser, and N. El-Solh. 2004. DNA macroarray for identification and typing of Staphylococcus aureus isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 422054-2064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tristan, A., L. Ying, M. Bes, J. Etienne, F. Vandenesch, and G. Lina. 2003. Use of multiplex PCR to identify Staphylococcus aureus adhesins involved in human hematogenous infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 414465-4467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Griethuysen, A., I. van Loo, A. van Belkum, C. Vandenbroucke-Grauls, W. Wannet, P. van Keulen, and J. Kluytmans. 2005. Loss of the mecA gene during storage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 431361-1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vernet, G., C. Jay, M. Rodrigue, and A. Troesch. 2004. Species differentiation and antibiotic susceptibility testing with DNA microarrays. J. Appl. Microbiol. 9659-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.