Abstract

Mice lacking the Stat1 interferon signaling gene were infected with herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) or an attenuated recombinant lacking virion host shutoff (Δvhs). Δvhs virus-infected Stat1−/− mice showed levels of replication equivalent to that of the wild-type virus-infected control mice but reduced relative to wild-type virus-infected Stat1−/− mice. Stat1 deficiency relieves the immunomodulatory deficiency of Δvhs virus, but not its inherent growth defect. Also Vhs is dispensable for reactivation.

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) is a ubiquitous human pathogen capable of causing frequent morbidity, although severe disease and mortality are relatively rare. Many of the severe and life-threatening cases of HSV infection are associated with immunocompromised individuals, such as those lacking Stat1 or having interferon (IFN) signaling defects (1, 3). This lends relevance and credence to the many studies demonstrating susceptibility of Stat1−/− mice to a variety of pathogens. The outcome of a viral infection is believed to be largely determined by the host immune response and viral gene products that act to counter it. HSV codes for a number of gene products that act to antagonize both the innate and adaptive immune responses. One example is the gene that encodes virion host shutoff (Vhs), a virus-encoded RNase capable of degrading both host and viral mRNAs (11). One model for Vhs function is that it aids viral infection through depletion of host cell mRNA, allowing viral mRNA synthesis and processing to occur without competition. Approximately 200 copies of Vhs are packaged into the viral tegument, and thereby Vhs is able to target host cell mRNAs for degradation immediately following infection and prior to de novo viral gene expression (4, 5). In cell culture, Vhs-null viruses have only minor defects in replication but have increased sensitivity to IFN and increased dendritic cell activation (20, 26). In vivo, however, Vhs deletion mutants are profoundly attenuated in terms of replication, virulence, and pathogenesis (22, 25). The significant attenuation of Vhs-null viruses led to the idea of their use as live attenuated vaccines (10, 15, 27, 28). In vivo, Vhs plays a role in the evasion of nonspecific and innate defenses, although the precise mechanisms remain obscure (2, 13). In order to better understand this attenuation, a variety of immune-deficient and congenic control mice were infected in this study with a Vhs-null virus and assayed for replication and virulence relative to a wild-type virus. Furthermore, given the interest in Vhs mutants as live attenuated vaccines, it was of interest to examine their pathogenesis in various immune-deficient mice to assess their potential safety in immunocompromised individuals.

Throughout this study, equal numbers of male and female mice were anesthetized and their corneas were bilaterally scarified and inoculated with either a wild-type (WT) virus (strain KOS) (21) or the Vhs-null virus (UL41NHB, herein referred to as Δvhs virus) (25) by adding 2 × 106 PFU/eye in a 5-μl volume. At the indicated time postinfection, mice were sacrificed and eye swab material, trigeminal ganglia, 6-mm biopsy punches of periocular skin, and brains were collected and assayed for virus by a standard plaque assay as previously described (17). Mice were housed and treated in accordance with all federal and university policies.

Previously, we reported that replication of an attenuated Vhs-null virus was not altered in RNase L-deficient or RNA-dependent protein kinase-deficient mice, and there was only a partial restoration of growth in mice lacking the type I and type II IFN receptors (13, 23). In the current study, the replication of Δvhs virus in the cornea was unaltered in either 129SvEv Rag2−/− mice (deficient for T and B cells) or BALB/c gld/lpr mice (Fas and Fas ligand deficient) relative to WT control mice (data not shown). The unaltered replication in the Rag2−/− mice was consistent with previous data (2).

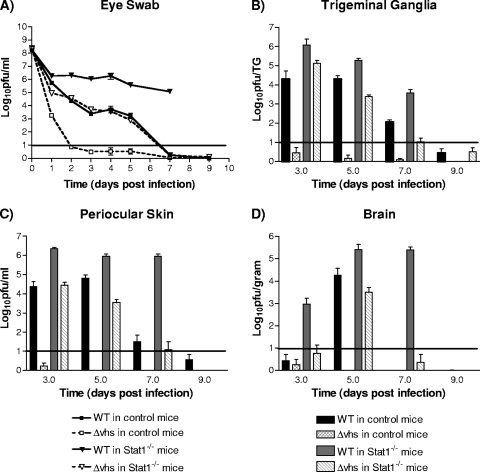

The rapid clearance of the Δvhs virus from mice lacking T and B cells, along with the fact that Vhs-null viruses are more sensitive to IFN, supported the idea that the innate immune response, rather than the adaptive immune response, was responsible for the attenuation of Δvhs virus. We next focused on mice lacking the IFN signaling factor Stat1 (14), a crucial component of the innate immune response. In corneas of 129 strain control mice, WT virus replicated to high titers in corneas (6 × 104 PFU per ml on day 2) out to 5 days postinfection (dpi) (Fig. 1A). In contrast, Δvhs virus only replicated to low titers (<1 × 101 PFU per ml on day 2) and was cleared rapidly from the corneas within 3 days. In Stat1−/− mice, the WT virus replication was enhanced (3 × 106 PFU per ml on day 2) and prolonged and mice succumbed to infection between 7 and 8 dpi. The replication of Δvhs virus, however, was also enhanced (7 × 104 PFU per ml on day 2), in contrast to its phenotype in control mice. Remarkably, these levels of Δvhs virus replication were comparable to those observed for WT virus in control mice.

FIG. 1.

Acute replication in corneas, trigeminal ganglia, periocular skin, and brain. Corneas of control 129 and Stat1−/− mice were scarified and inoculated with 2 × 106 PFU/eye. Titers were derived from tissues harvested from at least three separate lots of infected mice, with two to four mice harvested per time point. (A) Eye swabs were taken at indicated times postinfection, and titers were determined on Vero cells. Trigeminal ganglia (B), periocular skin (C), and brains (D) were harvested at the indicated times postinfection and homogenized, and viral titers were measured on Vero cells.

Similar patterns of viral replication were observed in the trigeminal ganglia and periocular skin tissues in the control and Stat1−/− mice (Fig. 1B and C). In Stat1−/− mice, the titer of WT virus was consistently 10-fold greater than that observed in the control mice. In control mice, Δvhs virus replication was scarcely detectable at any time point in either tissue, with titers at or below the limit of detection. In contrast, the peak Δvhs virus titers in Stat1−/− mice were significantly enhanced and comparable to titers of WT virus in control mice. The clearance of Δvhs virus from the Stat1−/− mice, however, was faster than that seen for WT virus infection of the control mice. Following corneal inoculation of the control mice, the WT virus was detectable in brain tissue on 5 dpi, while Δvhs virus was never detectable (Fig. 1D). In brains of Stat1−/− mice, WT virus was detected earlier than in control mice and the titers remained elevated out to 7 dpi. The Δvhs virus was detectable in Stat1−/− brains with titers similar to that of WT virus in the control mice. We also found that both the WT and Δvhs virus-infected Stat1−/− mice experienced severe disease with significant weight loss and periocular pathology, suggesting a role for Stat1 in controlling the host response (T. Pasieka et al., submitted for publication). Yet, it was notable that mortality was observed only in the WT virus-infected Stat1−/− mice, indicative of a role for Vhs in neurovirulence (data not shown). Taken together, these results demonstrate a crucial role for Stat1-dependent pathways in controlling the growth of an attenuated virus.

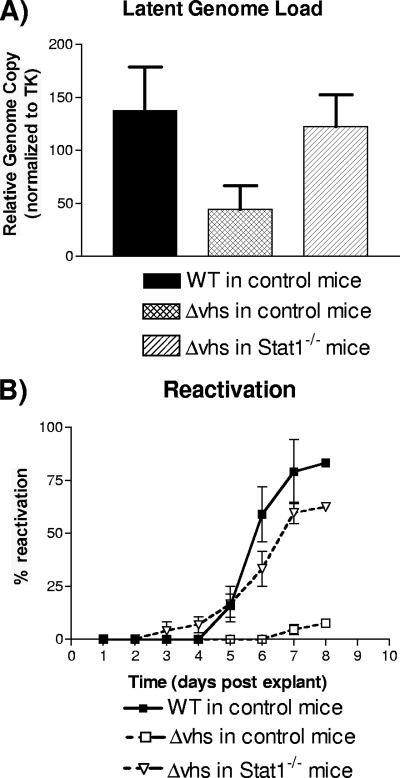

Previous work showed significantly reduced levels of establishment of and reactivation from latency by Δvhs virus following corneal inoculation compared to WT virus (25). It was not possible, therefore, to distinguish whether the failure of Δvhs virus to reactivate was a failure to establish latency or some inherent requirement for Vhs activity for reactivation from neurons. To address the contribution of Vhs to the establishment of or reactivation from latency, mice were again infected via the cornea. Establishment of latency was determined by real-time PCR to determine latent genome load in trigeminal ganglia as previously described (24). For normalization, mouse DNA standards were prepared from uninfected trigeminal ganglia, from which the copy number of the mouse adipsin gene was measured and used to normalize thymidine kinase copy number (24). Consistent with previous results (25), latently infected trigeminal ganglia from control mice infected with WT virus contained significantly more HSV genomes per cell than Δvhs virus-infected control mice (Fig. 2A). In the Stat1−/− mice, however, the Δvhs virus had copy numbers of latent virus genomes that were similar to those observed for WT virus in the control mice. The comparable copy numbers of latent WT virus genomes in the control mice and Δvhs genomes in the Stat1−/− mice provided a unique opportunity to assess the role of Vhs in reactivation. Reactivation of latent virus was measured by explant cocultivation as previously described (6). Using this assay, reactivation frequencies of the WT virus from the control mice and of the Δvhs virus from the Stat1−/− mice were similar (Fig. 2B). This assay confirms that Vhs is not inherently required for reactivation from latency. Rather, it is more likely that the apparent inability of Δvhs virus to reactivate stems from its inability to replicate robustly at the cornea and, as a result, its inability to establish WT virus levels of latent genomes.

FIG. 2.

Establishment of latency and reactivation from latency. Corneas of control 129 and Stat1−/− mice were scarified and inoculated with 2 × 106 PFU/eye. Trigeminal ganglia were harvested at 28 dpi. (A) Latent genome loads were measured in eight infected samples by real-time PCR of the thymidine kinase (TK) gene, using the mouse adipsin gene for normalization. (B) Reactivation of latent virus was measured from at least 18 mice, utilizing an explant cocultivation assay.

The inability of the Stat1−/− mice to initiate a proper IFN response leaves them highly susceptible to a variety of pathogens (9, 16), and the results presented herein are the first to show a restoration of the growth of a Δvhs virus to levels remarkably equivalent to those seen for WT virus in control mice. The replication of WT virus was also enhanced in Stat1−/− mice, further emphasizing the importance of Stat1-dependent pathways for controlling HSV infection. Perhaps the critical point, however, is that despite the loss of Stat1-dependent pathways, the Vhs-deleted virus remains attenuated compared to a WT virus. Together, these findings strongly suggest that loss of Stat1 relieves the loss of the immunomodulatory function of Vhs but cannot compensate for other inherent defects in this mutant. Many previous studies have noted the slight, yet highly reproducible, attenuation of a Vhs-null virus in vitro (12, 18, 19, 25). In a concurrent study, we found that Δvhs virus was attenuated in vitro during a multistep growth analysis in IFN-α/β/γR−/− mouse cells, further supporting our hypothesis of an inherent defect in Vhs-null viruses (16a). Further support comes from a recent study detailing changes in ICP4, ICP0, and glycoprotein trafficking in Vhs-null virus infected cells (8). Similar data were observed for a virus lacking ICP0, consistent with the multifunctional nature of these proteins (7).

A second key observation is that Vhs was dispensable for reactivation from latency. It is notable that previous studies showed that a virus lacking ICP0 was unable to reactivate from Stat1−/− trigeminal ganglia despite establishment of latency equivalent to that of a WT virus in control mice. ICP0 is required for efficient reactivation, and Stat1 deficiency could not overcome this requirement (7). This further supports our conclusion that Vhs is not required for reactivation but rather for the robust establishment of latency. Taken together, our observations of enhanced viral replication and induction of disease in Stat1−/− mice suggest that the virulence of even highly attenuated viruses may be a problem in certain immune-deficient populations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Patrick M. Stuart, Washington University, for providing the 129SvEv Rag2−/− and BALB/c Fas/FasL mice utilized in this study.

This work was supported by NIH grants to David Leib (EY10707), TracyJo Pasieka (1F32 AI65069-01A2), and the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences (P30EY02687). Support for the department from Research to Prevent Blindness and a Lew Wasserman Scholarship to David A. Leib is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 9 April 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Casrouge, A., S. Y. Zhang, C. Eidenschenk, E. Jouanguy, A. Puel, K. Yang, A. Alcais, C. Picard, N. Mahfoufi, N. Nicolas, L. Lorenzo, S. Plancoulaine, B. Senechal, F. Geissmann, K. Tabeta, K. Hoebe, X. Du, R. L. Miller, B. Heron, C. Mignot, T. B. de Villemeur, P. Lebon, O. Dulac, F. Rozenberg, B. Beutler, M. Tardieu, L. Abel, and J. L. Casanova. 2006. Herpes simplex virus encephalitis in human UNC-93B deficiency. Science 314308-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duerst, R. J., and L. A. Morrison. 2004. Herpes simplex virus 2 virion host shutoff protein interferes with type I interferon production and responsiveness. Virology 322158-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dupuis, S., E. Jouanguy, S. Al-Hajjar, C. Fieschi, I. Z. Al-Mohsen, S. Al-Jumaah, K. Yang, A. Chapgier, C. Eidenschenk, P. Eid, A. Al Ghonaium, H. Tufenkeji, H. Frayha, S. Al-Gazlan, H. Al-Rayes, R. D. Schreiber, I. Gresser, and J. L. Casanova. 2003. Impaired response to interferon-alpha/beta and lethal viral disease in human STAT1 deficiency. Nat. Genet. 33388-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feng, P., D. N. Everly, Jr., and G. S. Read. 2005. mRNA decay during herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections: protein-protein interactions involving the HSV virion host shutoff protein and translation factors eIF4H and eIF4A. J. Virol. 799651-9664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng, P., D. N. Everly, Jr., and G. S. Read. 2001. mRNA decay during herpesvirus infections: interaction between a putative viral nuclease and a cellular translation factor. J. Virol. 7510272-10280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gierasch, W. W., D. L. Zimmerman, S. L. Ward, T. K. Vanheyningen, J. D. Romine, and D. A. Leib. 2006. Construction and characterization of bacterial artificial chromosomes containing HSV-1 strains 17 and KOS. J. Virol. Methods 135197-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halford, W. P., C. Weisend, J. Grace, M. Soboleski, D. J. Carr, J. W. Balliet, Y. Imai, T. P. Margolis, and B. M. Gebhardt. 2006. ICP0 antagonizes Stat 1-dependent repression of herpes simplex virus: implications for the regulation of viral latency. Virol. J. 344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalamvoki, M., J. Qu, and B. Roizman. 2008. Translocation and colocalization of ICP4 and ICP0 in cells infected with herpes simplex virus 1 mutants lacking glycoprotein E, glycoprotein I, or the virion host shutoff product of the UL41 gene. J. Virol. 821701-1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karst, S. M., C. E. Wobus, M. Lay, J. Davidson, and H. W. Virgin IV. 2003. STAT1-dependent innate immunity to a Norwalk-like virus. Science 2991575-1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keadle, T. L., K. A. Laycock, J. L. Morris, D. A. Leib, L. A. Morrison, J. S. Pepose, and P. M. Stuart. 2002. Therapeutic vaccination with vhs(−) herpes simplex virus reduces the severity of recurrent herpetic stromal keratitis in mice. J. Gen. Virol. 832361-2365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwong, A. D., and N. Frenkel. 1987. Herpes simplex virus-infected cells contain a function(s) that destabilizes both host and viral mRNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 841926-1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwong, A. D., and N. Frenkel. 1989. The herpes simplex virus virion host shutoff function. J. Virol. 634834-4839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leib, D. A., T. E. Harrison, K. M. Laslo, M. A. Machalek, N. J. Moorman, and H. W. Virgin. 1999. Interferons regulate the phenotype of wild-type and mutant herpes simplex viruses in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 189663-672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meraz, M. A., J. M. White, K. C. Sheehan, E. A. Bach, S. J. Rodig, A. S. Dighe, D. H. Kaplan, J. K. Riley, A. C. Greenlund, D. Campbell, K. Carver-Moore, R. N. DuBois, R. Clark, M. Aguet, and R. D. Schreiber. 1996. Targeted disruption of the Stat1 gene in mice reveals unexpected physiologic specificity in the JAK-STAT signaling pathway. Cell 84431-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morrison, L. A., and D. M. Knipe. 1994. Immunization with replication-defective mutants of herpes simplex virus type 1: sites of immune intervention in pathogenesis of challenge virus infection. J. Virol. 68689-696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mumphrey, S. M., H. Changotra, T. N. Moore, E. R. Heimann-Nichols, C. E. Wobus, M. J. Reilly, M. Moghadamfalahi, D. Shukla, and S. M. Karst. 2007. Murine norovirus 1 infection is associated with histopathological changes in immunocompetent hosts, but clinical disease is prevented by STAT1-dependent interferon responses. J. Virol. 813251-3263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16a.Pasielka, T. J., B. Lu, S. D. Crosby, K. M. Wylie, L. A. Morrison, D. E. Alexander, V. D. Menachery, and D. A. Leib. 26 March 2008. Herpes simplex virus virion host shutoff attenuates establishment of the antiviral state. J. Virol. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02047-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Rader, K. A., C. E. Ackland-Berglund, J. K. Miller, J. S. Pepose, and D. A. Leib. 1993. In vivo characterization of site-directed mutations in the promoter of the herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcripts. J. Gen. Virol. 741859-1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Read, G. S., and N. Frenkel. 1983. Herpes simplex virus mutants defective in the virion-associated shutoff of host polypeptide synthesis and exhibiting abnormal synthesis of α (immediate early) viral polypeptides. J. Virol. 46498-512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Read, G. S., B. M. Karr, and K. Knight. 1993. Isolation of a herpes simplex virus type 1 mutant with a deletion in the virion host shutoff gene and identification of multiple forms of the vhs (UL41) polypeptide. J. Virol. 677149-7160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samady, L., E. Costigliola, L. MacCormac, Y. McGrath, S. Cleverley, C. E. Lilley, J. Smith, D. S. Latchman, B. Chain, and R. S. Coffin. 2003. Deletion of the virion host shutoff protein (vhs) from herpes simplex virus (HSV) relieves the viral block to dendritic cell activation: potential of vhs− HSV vectors for dendritic cell-mediated immunotherapy. J. Virol. 773768-3776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith, K. O. 1964. Relationship between the envelope and the infectivity of herpes simplex virus. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 115814-816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith, T. J., L. A. Morrison, and D. A. Leib. 2002. Pathogenesis of herpes simplex virus type 2 virion host shutoff (vhs) mutants. J. Virol. 762054-2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith, T. J., R. H. Silverman, and D. A. Leib. 2003. RNase L activity does not contribute to host RNA degradation induced by herpes simplex virus infection. J. Gen. Virol. 84925-928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strand, S. S., and D. A. Leib. 2004. Role of the VP16-binding domain of vhs in viral growth, host shutoff activity, and pathogenesis. J. Virol. 7813562-13572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strelow, L. I., and D. A. Leib. 1995. Role of the virion host shutoff (vhs) of herpes simplex virus type 1 in latency and pathogenesis. J. Virol. 696779-6786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzutani, T., M. Nagamine, T. Shibaki, M. Ogasawara, I. Yoshida, T. Daikoku, Y. Nishiyama, and M. Azuma. 2000. The role of the UL41 gene of herpes simplex virus type 1 in evasion of non-specific host defence mechanisms during primary infection. J. Gen. Virol. 811763-1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walker, J., K. A. Laycock, J. S. Pepose, and D. A. Leib. 1998. Postexposure vaccination with a virion host shutoff defective mutant reduces UV-B radiation-induced ocular herpes simplex virus shedding in mice. Vaccine 166-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walker, J., and D. A. Leib. 1998. Protection from primary infection and establishment of latency by vaccination with a herpes simplex virus type 1 recombinant deficient in the virion host shutoff (vhs) function. Vaccine 161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]