Abstract

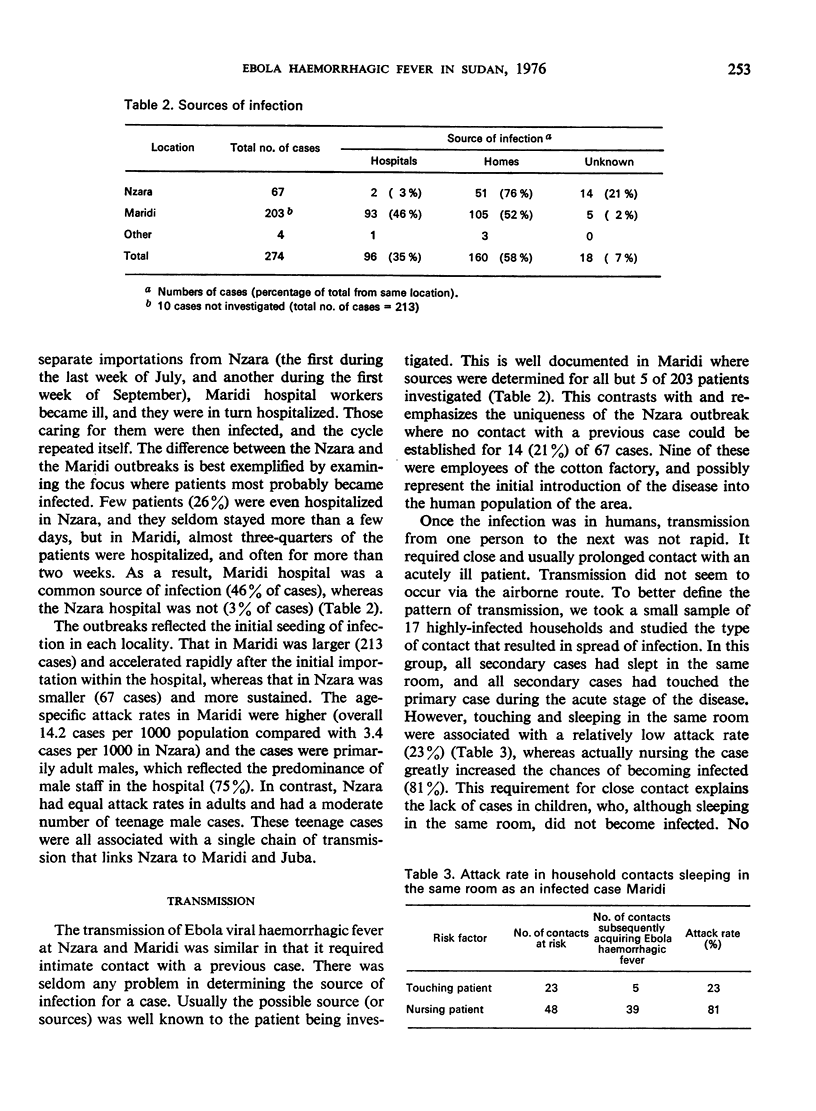

A large outbreak of haemorrhagic fever (subsequently named Ebola haemorrhagic fever) occurred in southern Sudan between June and November 1976. There was a total of 284 cases; 67 in the source town of Nzara, 213 in Maridi, 3 in Tembura, and 1 in Juba. The outbreak in Nzara appears to have originated in the workers of a cotton factory. The disease in Maridi was amplified by transmission in a large, active hospital. Transmission of the disease required close contact with an acute case and was usually associated with the act of nursing a patient. The incubation period was between 7 and 14 days. Although the link was not well established, it appears that Nzara could have been the source of infection for a similar outbreak in the Bumba Zone of Zaire.

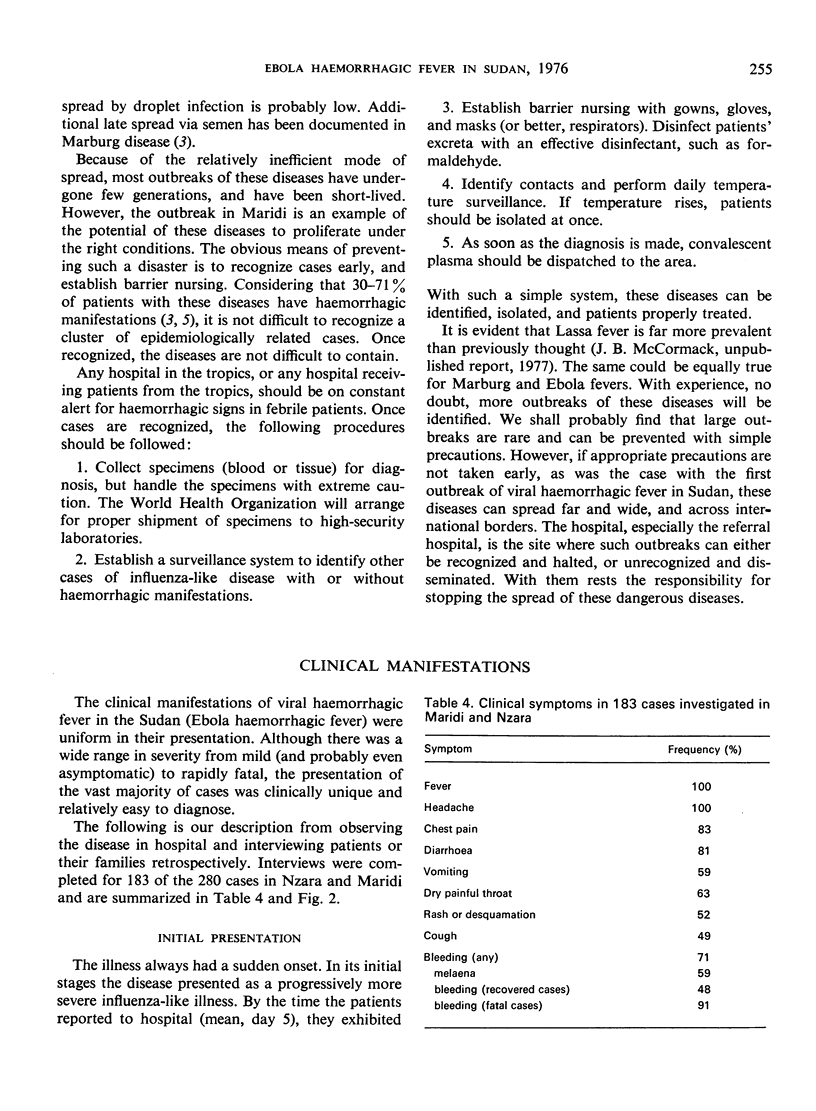

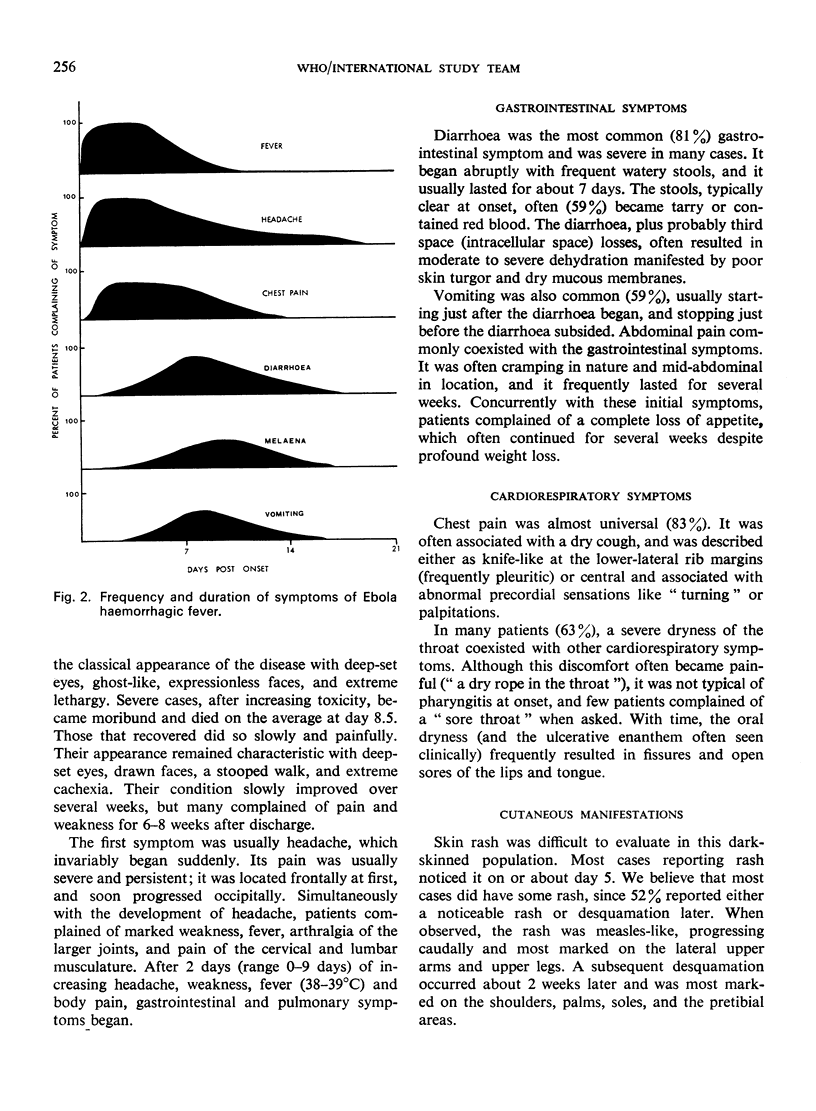

In this outbreak Ebola haemorrhagic fever was a unique clinical disease with a high mortality rate (53% overall) and a prolonged recovery period in those who survived. Beginning with an influenza-like syndrome, including fever, headache, and joint and muscle pains, the disease soon caused diarrhoea (81%), vomiting (59%), chest pain (83%), pain and dryness of the throat (63%), and rash (52%). Haemorrhagic manifestations were common (71%), being present in half of the recovered cases and in almost all the fatal cases.

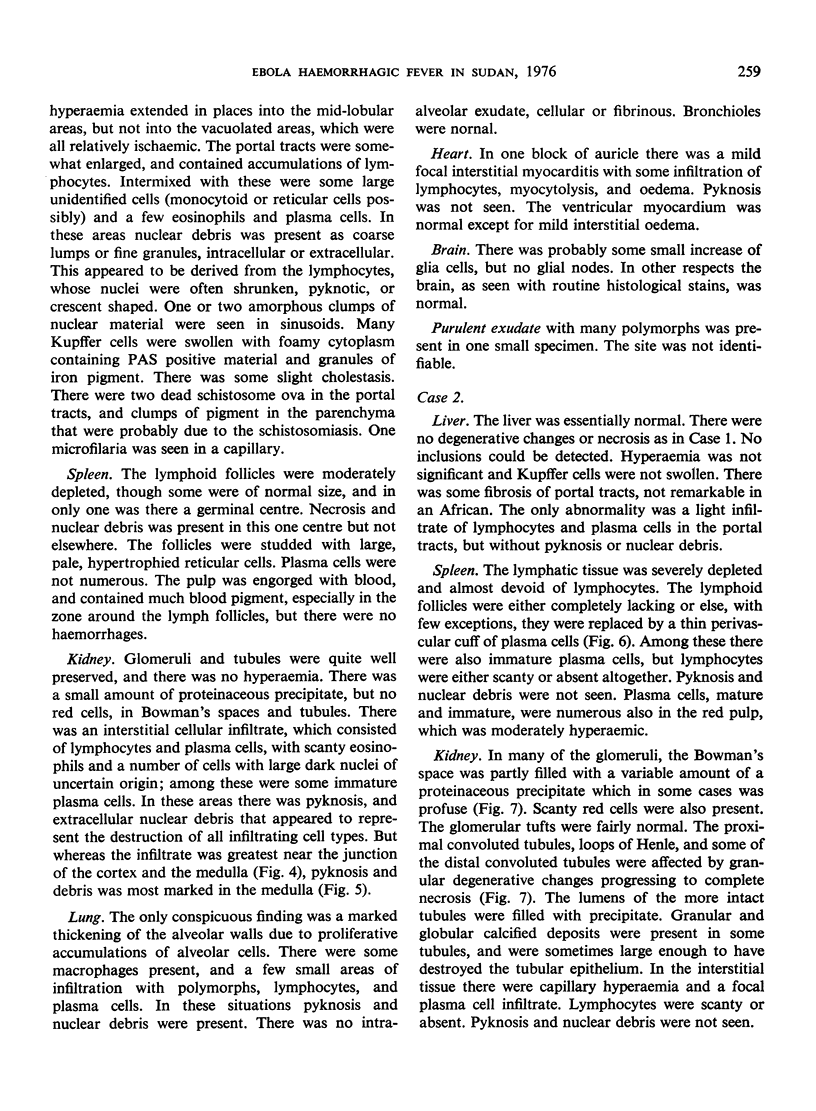

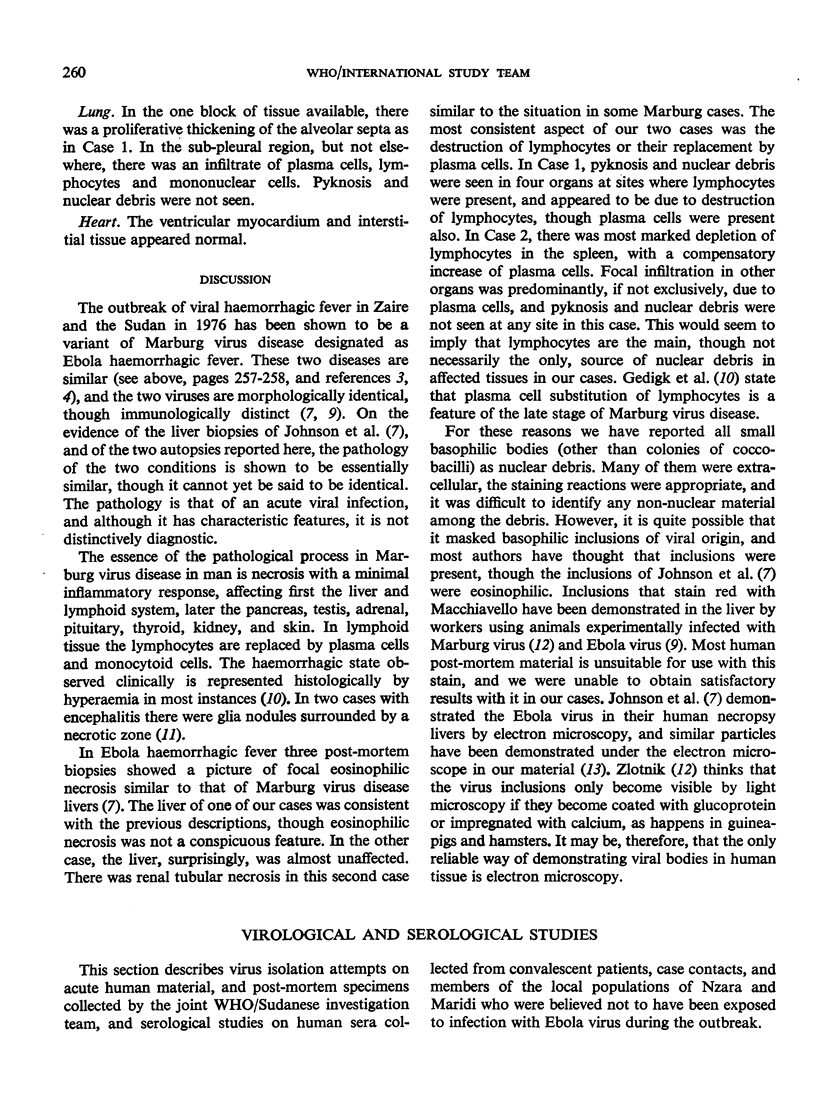

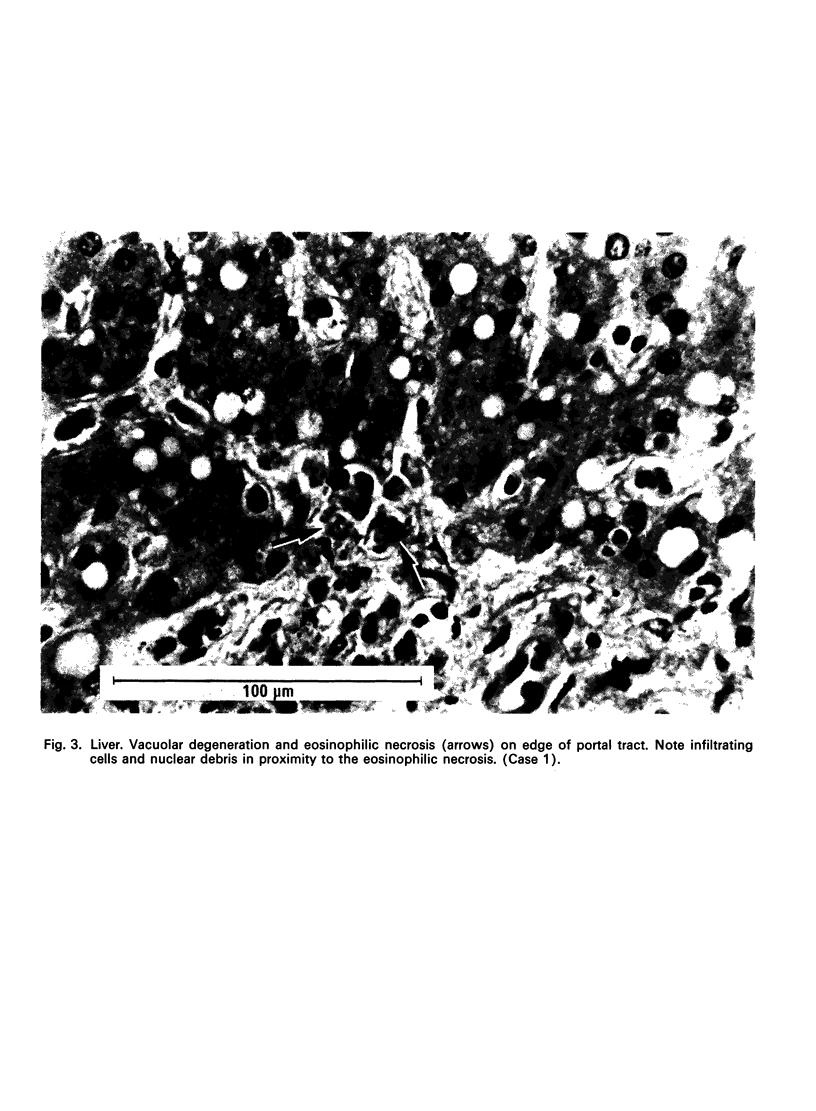

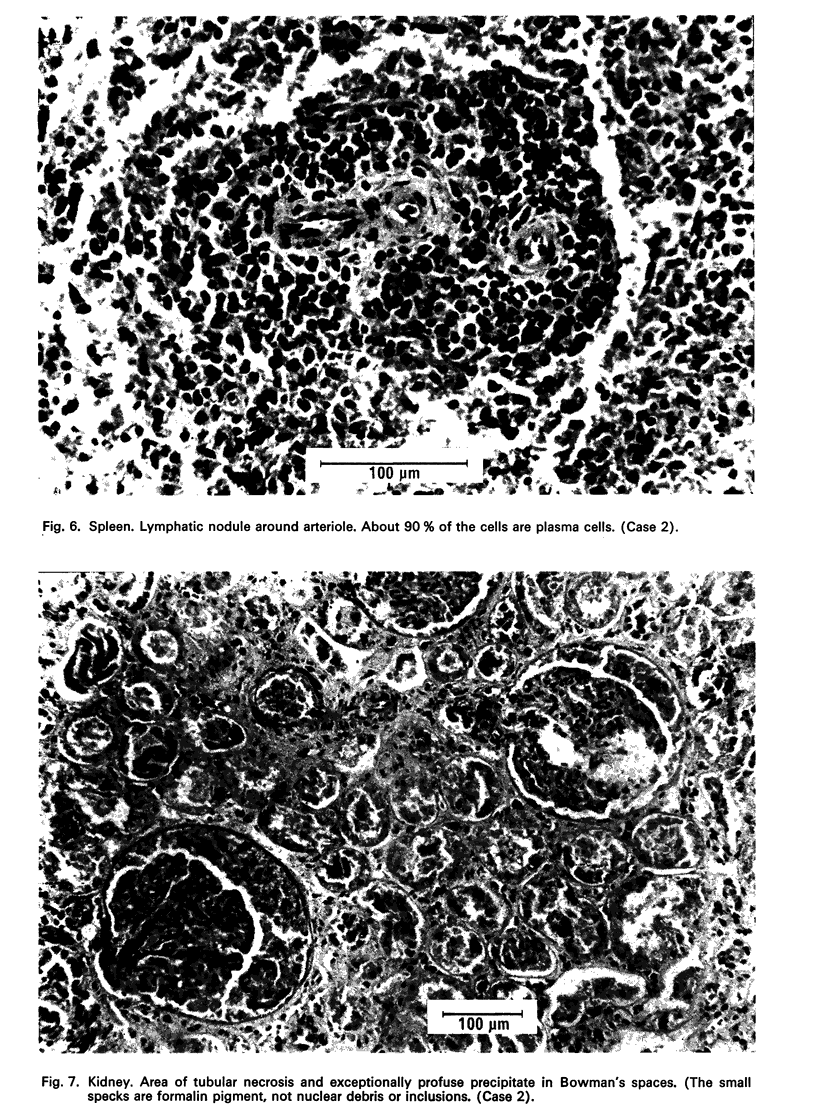

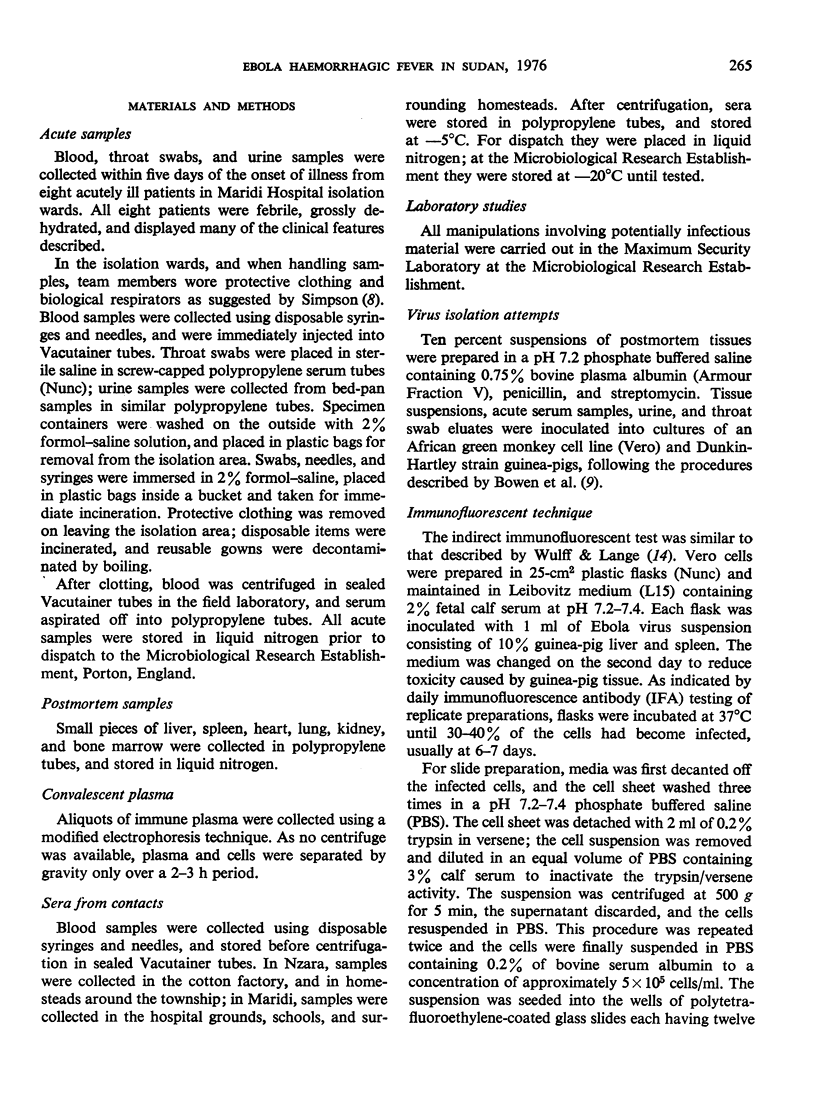

Two post mortems were carried out on patients in November 1976. The histopathological findings resembled those of an acute viral infection and although the features were characteristic they were not exclusively diagnostic. They closely resembled the features described in Marburg virus infection, with focal eosinophilic necrosis in the liver and destruction of lymphocytes and their replacement by plasma cells. One case had evidence of renal tubular necrosis.

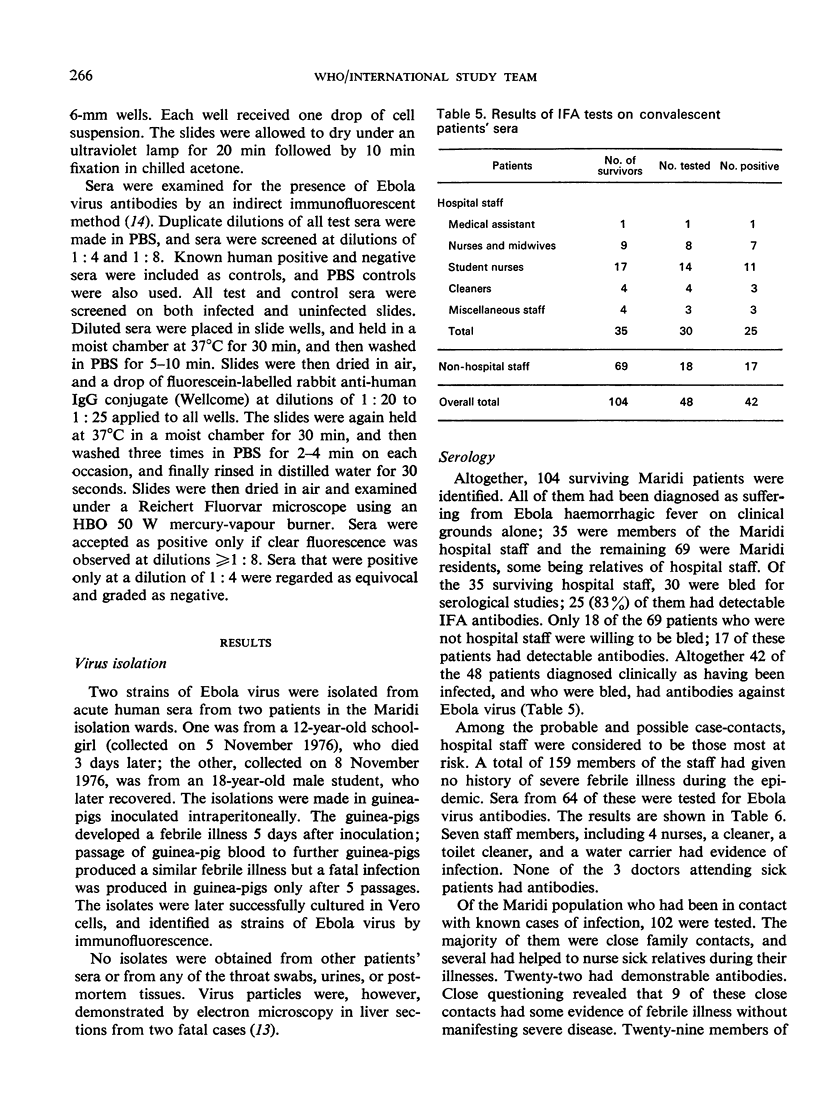

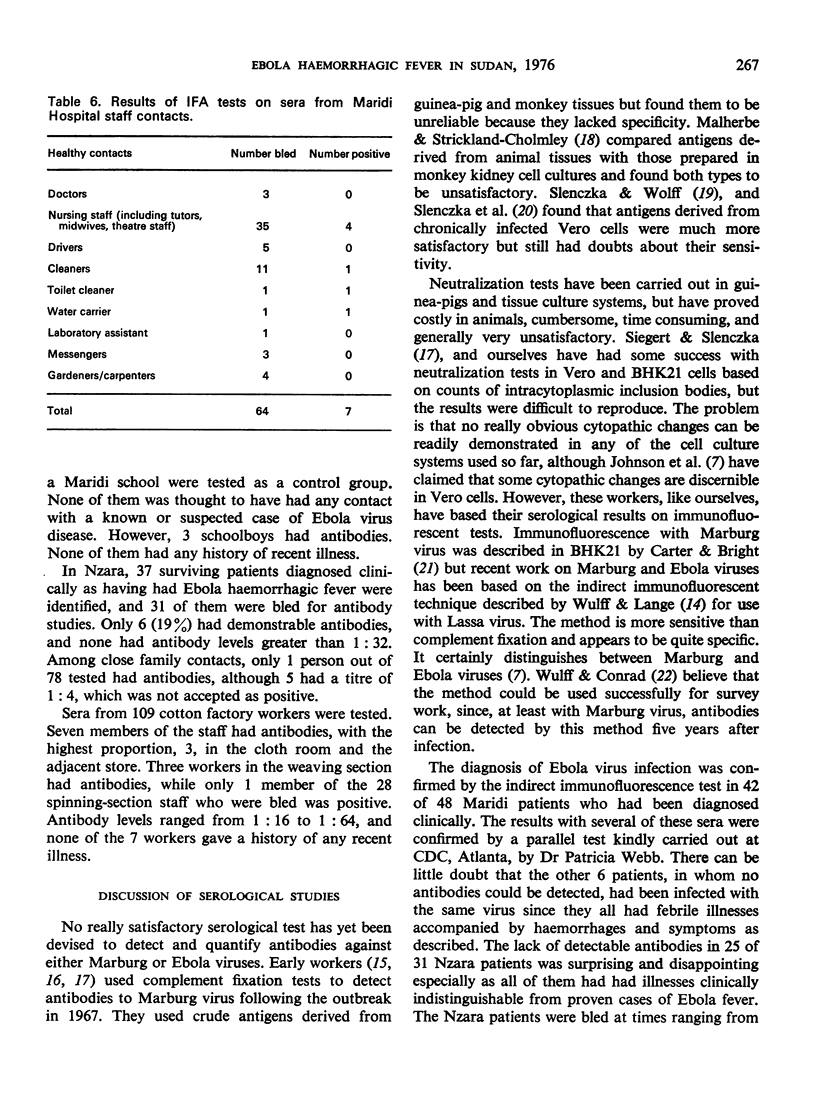

Two strains of Ebola virus were isolated from acute phase sera collected from acutely ill patients in Maridi hospital during the investigation in November 1976. Antibodies to Ebola virus were detected by immunofluorescence in 42 of 48 patients in Maridi who had been diagnosed clinically, but in only 6 of 31 patients in Nzara. The possibility of the indirect immunofluorescent test not being sufficiently sensitive is discussed.

Of Maridi case contacts, in hospital and in the local community, 19% had antibodies. Very few of them gave any history of illness, indicating that Ebola virus can cause mild or even subclinical infections. Of the cloth room workers in the Nzara cotton factory, 37% appeared to have been infected, suggesting that the factory may have been the prime source of infection.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bechtelsheimer H., Jacob H., Solcher H. The neuropathology of an infectious disease transmitted by African green monkeys (Cercopithecus aethiops). Ger Med Mon. 1969 Jan;14(1):10–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen E. T., Lloyd G., Harris W. J., Platt G. S., Baskerville A., Vella E. E. Viral haemorrhagic fever in southern Sudan and northern Zaire. Preliminary studies on the aetiological agent. Lancet. 1977 Mar 12;1(8011):571–573. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)92001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey D. E., Kemp G. E., White H. A., Pinneo L., Addy R. F., Fom A. L., Stroh G., Casals J., Henderson B. E. Lassa fever. Epidemiological aspects of the 1970 epidemic, Jos, Nigeria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1972;66(3):402–408. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(72)90271-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter G. B., Bright W. F. Immunofluorescent study of the vervet monkey disease agent. Lancet. 1968 Oct 26;2(7574):913–914. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(68)91080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K. M., Lange J. V., Webb P. A., Murphy F. A. Isolation and partial characterisation of a new virus causing acute haemorrhagic fever in Zaire. Lancet. 1977 Mar 12;1(8011):569–571. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)92000-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissling R. E., Robinson R. Q., Murphy F. A., Whitfield S. G. Agent of disease contracted from green monkeys. Science. 1968 May 24;160(3830):888–890. doi: 10.1126/science.160.3830.888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens P. E., Patton R., Baum J. J., Monath T. P. Clinical presentation of Lassa fever cases during the hospital epidemic at Zorzor, Liberia, March-April 1972. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1973 Nov;22(6):780–784. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1973.22.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monath T. P., Mertens P. E., Patton R., Moser C. R., Baum J. J., Pinneo L., Gary G. W., Kissling R. E. A hospital epidemic of Lassa fever in Zorzor, Liberia, March-April 1972. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1973 Nov;22(6):773–779. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1973.22.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slenczka W., Wolff G., Siegert R. A critical study of monkey sera for the presence of antibody against the Marburg virus. Am J Epidemiol. 1971 Jun;93(6):496–505. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C. E., Simpson D. I., Bowen E. T., Zlotnik I. Fatal human disease from vervet monkeys. Lancet. 1967 Nov 25;2(7526):1119–1121. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(67)90621-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troup J. M., White H. A., Fom A. L., Carey D. E. An outbreak of Lassa fever on the Jos plateau, Nigeria, in January-February 1970. A preliminary report. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1970 Jul;19(4):695–696. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1970.19.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulff H., Lange J. V. Indirect immunofluorescence for the diagnosis of Lassa fever infection. Bull World Health Organ. 1975;52(4-6):429–436. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]