Abstract

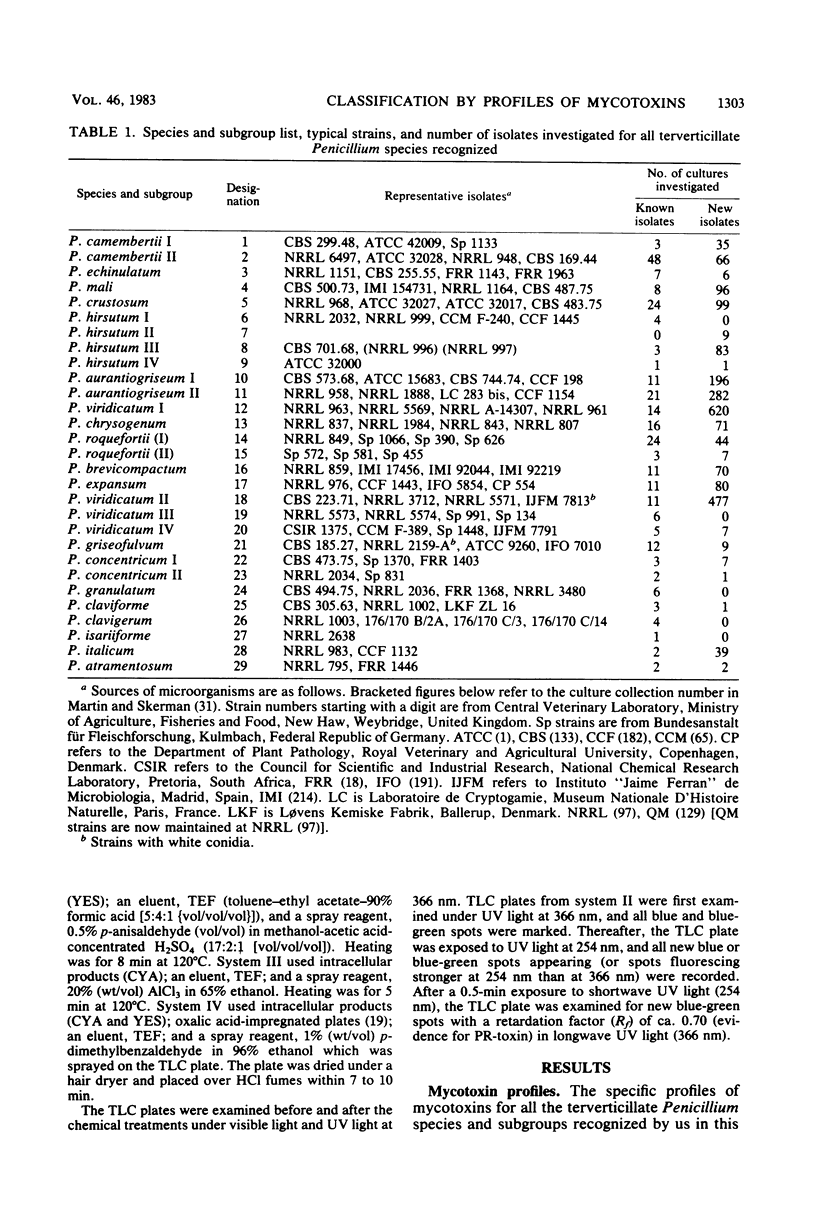

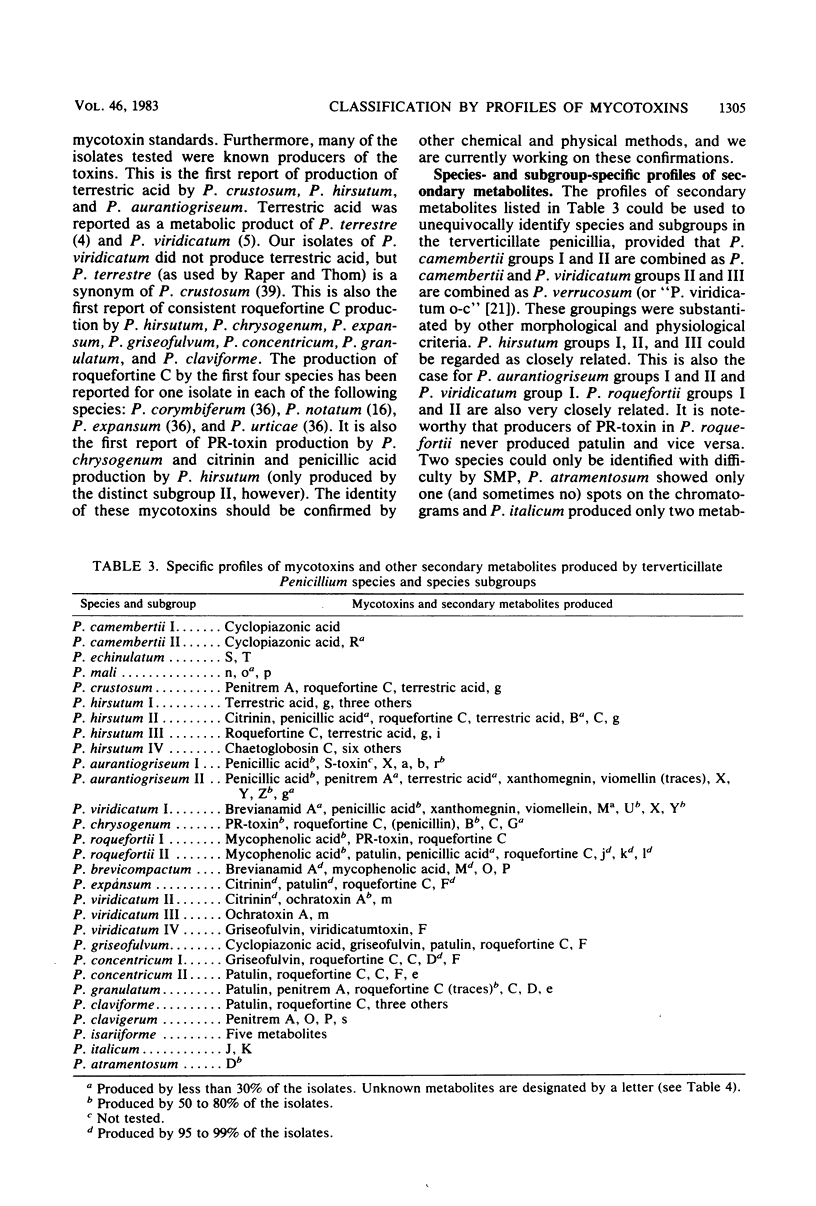

Strains of available terverticillate penicillium species and varieties were analyzed for profiles of known mycotoxins and other secondary metabolites produced on Czapek yeast autolysate agar (intracellular metabolites) and yeast extract-sucrose agar (extracellular metabolites) by using simple thin-layer chromatography screening techniques. These strains (2,473 in all) could be classified into 29 groups based on profiles of secondary metabolites. Most of these profiles of secondary metabolites were distinct, containing several biosynthetically different mycotoxins and unknown metabolites characterized by distinct colors and retardation factors on thin-layer chromatography plates. Some species (P. italicum and P. atramentosum) only produced one or two metabolites by the simple screening methods. The 29 groups based on profiles of secondary metabolites were known species or subgroups thereof. These species and subgroups were independently identifiable by using morphological and physiological criteria. The species accepted, the number of isolates in each species investigated, and the mycotoxins they produced were: P. atramentosum, 4; P. aurantiogriseum, 510 (group I: penicillic acid and S-toxin and group II: penicillic acid, penitrem A [low frequency], terrestric acid [low frequency], viomellein, and xanthomegnin); P. brevicompactum, 81 (brevianamid A and mycophenolic acid); P. camembertii group I, 38, and group II, 114 (cyclopiazonic acid); P. chrysogenum, 87 (penicillin, roquefortine C, and PR-toxin); P. claviforme, 4 (patulin and roquefortine C); P. clavigerum, 4 (penitrem A); P. concentricum group I, 10 (griseofulvin and roquefortine C), and group II, 3 (patulin and roquefortine C); P. crustosum, 123 (penitrem A, roquefortine C, and terrestric acid); P. echinulatum, 13; P. expansum, 91 (citrinin, patulin, and roquefortine C); P. granulatum, 6 (patulin, penitrem A, and roquefortine C [traces]); P. griseofulvum, 21 (cyclopiazonic acid, griseofulvin, patulin, and roquefortine C); P. hirsutum, 100 (group I: terrestric acid; group II: citrinin, penicillic acid , roquefortine C, and terrestric acid; and group III: roquefortine C and terrestric acid), P. hirsutum group IV, 2 (chaetoglobosin C); P. isariiforme, 1; P. italicum, 41; P. mali, 104; P. roquefortii, 78 (group I: mycophenolic acid, PR-toxin, and roquefortine C and group II: mycophenolic acid, patulin, penicillic acid [low frequency], and roquefortine C); P. viridicatum group I, 634 (brevianamid A [low frequency], penicillic acid, viomellein, and xanthomegnin), P. viridicatum group II and III, 494 (citrinin and ochratoxin A), P. viridicatum group IV, 12 (griseofulvin and viridicatumtoxin). It is proposed that profiles of secondary metabolites be strongly emphasized in any future revision of the penicillia.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- BIRKINSHAW J. H., SAMANT M. S. Studies in the biochemistry of micro-organisms. 107. Metabolites of Penicillium viridicatum Westling: viridicatic acid (ethylcarlosic acid). Biochem J. 1960 Feb;74:369–373. doi: 10.1042/bj0740369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird B. A., Remaley A. T., Campbell I. M. Brevianamides A and B Are Formed Only After Conidiation Has Begun in Solid Cultures of Penicillium brevicompactum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1981 Sep;42(3):521–525. doi: 10.1128/aem.42.3.521-525.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkinshaw J. H., Raistrick H. Studies in the biochemistry of micro-organisms: Isolation, properties and constitution of terrestric acid (ethylcarolic acid), a metabolic product of Penicillium terrestre Jensen. Biochem J. 1936 Dec;30(12):2194–2200. doi: 10.1042/bj0302194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CUNNINGHAM K. G., FREEMAN G. G. The isolation and some chemical properties of viridicatin, a metabolic product of Penicillium viridicatum Westling. Biochem J. 1953 Jan;53(2):328–332. doi: 10.1042/bj0530328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciegler A., Fennell D. I., Sansing G. A., Detroy R. W., Bennett G. A. Mycotoxin-producing strains of Penicillium viridicatum: classification into subgroups. Appl Microbiol. 1973 Sep;26(3):271–278. doi: 10.1128/am.26.3.271-278.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciegler A., Pitt J. I. Survey of the genus Penicillium for tremorgenic toxin production. Mycopathol Mycol Appl. 1970 Dec 28;42(1):119–124. doi: 10.1007/BF02051832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel G., von Milczewski K. E., Prokopek D., Teuber M. Strain-Specific Synthesis of Mycophenolic Acid by Penicillium roqueforti in Blue-Veined Cheese. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982 May;43(5):1034–1040. doi: 10.1128/aem.43.5.1034-1040.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filtenborg O., Frisvad J. C., Svendsen J. A. Simple screening method for molds producing intracellular mycotoxins in pure cultures. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983 Feb;45(2):581–585. doi: 10.1128/aem.45.2.581-585.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisvad J. C. A selective and indicative medium for groups of Penicillium viridicatum producing different mycotoxins in cereals. J Appl Bacteriol. 1983 Jun;54(3):409–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1983.tb02636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisvad J. C. Physiological criteria and mycotoxin production as AIDS in identification of common asymmetric penicillia. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1981 Mar;41(3):568–579. doi: 10.1128/aem.41.3.568-579.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghani H. M., Lancaster J. H., Larsh H. W. Chromatographic separation of pigments produced by Arthroderma benhamiae. Sabouraudia. 1975 Mar;13(Pt 1):89–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha-Huy-Kê, Luckner M. Structure and function of the conidiospore pigments of Penicillium cyclopium. Z Allg Mikrobiol. 1979;19(2):117–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison R. D., Steyn P. S., Van Rensburg S. J. Viridicatumtoxin, a new mycotoxin from Penicillium viridicatum Westling. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1973 Mar;24(3):507–509. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(73)90057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh P., Hasselager E., Friis P. Studies on fungal nephrotoxicity. 2. Isolation of two nephrotoxic compounds from Penicillium viridicatum Westling: citrinin and oxalic acid. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand B Microbiol Immunol. 1970;78(4):401–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson R. A., Eckardt C., Orth R. The taxonomy of Penicillium species from fermented cheeses. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1977;43(3-4):341–350. doi: 10.1007/BF02313761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott P. M., Lawrence J. W., van Walbeek W. Detection of mycotoxins by thin-layer chromatography: application to screening of fungal extracts. Appl Microbiol. 1970 Nov;20(5):839–842. doi: 10.1128/am.20.5.839-842.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stack M. E., Mislivec P. B. Production of xanthomegnin and viomellein by isolates of Aspergillus ochraceus, Penicillium cyclopium, and Penicillium viridicatum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1978 Oct;36(4):552–554. doi: 10.1128/aem.36.4.552-554.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson B. J., Yang D. T., Harris T. M. Production, isolation, and preliminary toxicity studies of brevianamide A from cultures of Penicillium viridicatum. Appl Microbiol. 1973 Oct;26(4):633–635. doi: 10.1128/am.26.4.633-635.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Walbeek W., Scott P. M., Harwig J., Lawrence J. W. Penicillium viridicatum Westling: a new source of ochratoxin A. Can J Microbiol. 1969 Nov;15(11):1281–1285. doi: 10.1139/m69-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]