Abstract

We have developed a simplified, efficient approach for the 3D reconstruction and analysis of mammalian cells in toto by electron microscope tomography (ET), to provide quantitative information regarding ‘global’ cellular organization at ~15–20 nm resolution. Two insulin-secreting beta cells - deemed ‘functionally equivalent’ by virtue of their location at the periphery of the same pancreatic islet - were reconstructed in their entirety in 3D after fast-freezing/freeze-substitution/plastic embedment in situ within a glucose-stimulated islet of Langerhans isolated intact from mouse pancreata. These cellular reconstructions have afforded several unique insights into fundamental structure-function relationships among key organelles involved in the biosynthesis and release of the crucial metabolic hormone, insulin, that could not be provided by other methods. The Golgi ribbon, mitochondria and insulin secretory granules in each cell were segmented for comparative analysis. We propose that relative differences between the two cells in terms of the number, dimensions and spatial distribution (and for mitochondria, also the extent of branching) of these organelles per cubic micron of cellular volume reflects differences in the two cells’ individual capacity (and/or readiness) to respond to secretagogue stimulation, reflected by an apparent inverse relationship between the number/size of insulin secretory granules versus the number/size of mitochondria and the Golgi ribbon. We discuss the advantages of this approach for quantitative cellular ET of mammalian cells, briefly discuss its application relevant to other complementary techniques, and summarize future strategies for overcoming some of its current limitations.

Keywords: cellular tomography, 3D reconstruction, mammalian, insulin secretion, beta cell, islets of Langerhans, montaging, segmentation, automation, transforms, insulin, electron microscope tomography, Golgi, pancreas, secretory granules, trans-Golgi, endocrine, exocytosis, cytoskeleton

INTRODUCTION

Studying cell biology/physiology at the electron microscopic (EM) level, particularly in the context of intact native tissue with biomedical relevance to human/public health, has emerged as a major goal of the complex systems and computational biology research communities over the past few years (Arita et al., 2005; Bork and Serrano, 2005; Burrage et al., 2006; Coggan et al., 2005). Moreover, building on a precise spatio-temporal scaffold in all four dimensions (4D) is increasingly regarded as a basic tenet to developing a sufficient understanding of the cell as a unitary complex system, and as a prerequisite for in silico efforts at cell simulation (Bork and Serrano, 2005; Lehner et al., 2005; Nickell et al., 2006). Indeed, much of the work carried out over the past 40 years or so to elucidate the insulin biosynthetic pathway within the beta cells of the endocrine pancreas has relied heavily on a rigorous structure-function based approach using conventional 2D EM techniques as well as rudimentary 3D studies of serial paraffin sections (Bonner-Weir, 1988; Bonner-Weir, 1989; Bonner-Weir and Orci, 1982; Greider et al., 1969; Howell and Tyhurst, 1974; Howell et al., 1969; Orci, 1974; Orci, 1976a; Orci, 1976b; Orci, 1985; Orci et al., 1984).

Together, these studies have contributed significantly to our overall understanding of the key steps involved in insulin manufacture and release. However, real gaps still remain in our basic knowledge of the insulin biosynthetic pathway from molecule-to-cell, and from cell-to-tissue. This led us several years ago to develop techniques for the improved preservation and subsequent 3D imaging of insulin-secreting cells by EM tomography (ET), first using immortalized beta cell lines (Marsh et al., 2001b), then with beta cells still resident in situ in pancreatic islets isolated from mice (Marsh et al., 2004). Although the tomograms generated from these studies have provided (and continue to provide) exciting new insights into structure-function relationships among organelles of the insulin biosynthetic pathway at comparatively high (~5–7 nm) resolution (Marsh et al., 2001a; Marsh et al., 2004; Marsh et al., 2001b; Mogelsvang et al., 2004), they are limited in that they normally only allow the detailed examination of a relatively small percentage (i.e. ≤1%) of the total cell volume due to the significant technical challenges associated with high-resolution ET of large cellular volumes (Marsh, 2005; Marsh, 2007).

To both qualitatively and quantitatively assess relationships among the key organelles involved in insulin production in the context of the whole cell, we recently undertook the development and application of an expedited ET approach that would allow us to image, reconstruct and analyze entire pancreatic beta cells in detail (≤20 nm) in 3D, at an order of magnitude better resolution than standard light microscopy (LM) and at least twice the resolution of the most promising approaches in 3D and 4D LM (Egner et al., 2004; Hara et al., 2006; Ma et al., 2004; Michael et al., 2004). While limited by the fact that when compared to live cell imaging we are restricted to viewing a single static “3D snapshot”, we retain the advantage of having sufficient resolution to visually/morphologically distinguish most compartments/organelles of interest at once (based on a wealth of elegant ultrastructural studies of mammalian membrane traffic over the past six decades), as opposed to only being able to visualize those compartments that traffic and/or house a protein(s) of interest tagged with a fluorophore(s). Our primary criteria for establishing an appropriate schema was that it must provide a means for comparative whole cell studies of islet/beta cell biology by ET in a way that was fiscally/temporally practical, and would lend itself to attempts at automation. Thus, we imaged and reconstructed two beta cells from the same glucose-stimulated mouse islet by single-axis, serial section ET at magnifications of 4700× and 3900×, respectively, that resulted in whole cell tomograms with a final resolution of ~15–20 nm. In addition, we developed several new methods for the abbreviated segmentation of cellular organelles/compartments that allowed us to segment the entire Golgi ribbon as well as both cells’ full complement of mitochondria and insulin secretory granules for comparative analysis, on a timescale of weeks rather than months. We propose that although relatively crude, this approach affords important new insights into global cellular organization and comparative cell biology in 3D that cannot be attained by other methods.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Islet isolation and culture

Islets of Langerhans were isolated intact from mouse pancreas by intra-ductal collagenase injection/digestion and purified as previously described (Gotoh et al., 1985; Marsh et al., 2004; Nicolls et al., 2002). After manually picking individual islets to minimize exocrine tissue contamination, islets were cultured in RPMI medium containing 10% (v/v) newborn calf serum (NCS) or fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen, Australia) and 7 mM D-glucose equilibrated with 5% CO2 at 37°C. The medium was additionally supplemented with L-glutamine and 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA). Following culture for 2–3 hours for tissue recovery and to promote re-initiation of protein synthesis, islets were transferred to RPMI medium containing low glucose (3 mM) and cultured overnight. Islets were then transferred to medium containing a physiologically-relevant stimulatory concentration (11 mM) of D-glucose for one hour before high pressure freezing to maximally upregulate proinsulin biosynthesis.

High-pressure freezing and freeze-substitution fixation

Islet cultures were maintained at 37°C in HEPES -buffered (10mM) RPMI medium (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) containing either NCS or FBS 10% (v/v) (Invitrogen, Australia) prior to freezing. Immediately prior to freezing, 10–30 islets (depending on size) were manually transferred by pipette into interlocking brass planchettes (Swiss Precision Inc., CA, USA), also pre-warmed to 37°C, under a dissecting microscope (Olympus, Australia). Islets were high-pressure frozen using a Balzers HPM010 high-pressure freezer (BAL-TEC AG, Liechtenstein) and stored under liquid nitrogen. Specimens were freeze-substituted and plastic-embedded essentially as described previously (Marsh et al., 2001b).

Microtomy and preparation for EM

Ribbons of thin (40–60 nm) or thick (300–400 nm) sections were cut on a microtome (Leica-Microsystems) for conventional 2D survey at 80–100 keV to assess the quality of islet preservation or for 3D studies by ET at 300 keV on Tecnai T12 and F30 microscopes, respectively (FEI Company). Typically, ribbons of serial thick sections collected onto formvar-coated copper (2 × 1 mm) slot grids (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and post-stained with 2% aqueous uranyl acetate (UA) and Reynold’s lead citrate require an additional carbon-coating step to minimize charging/movement in the electron beam, particularly when tilted for tomography (Marsh, 2005; Marsh, 2007). Slot grids are normally used because they have - to date - afforded the maximal possible unobstructed viewing area when the specimen is tilted beyond 60° in the EM. However, since ribbons of serial sections are essentially laid down the length of the grid parallel to the slot itself, tomographic ‘tilt series’ collected around the orthogonal axis are often limited to tilt angles lower than 60° because the metal of the specimen support grid obstructs the electron beam at high tilt. The limiting factor to using grids that provide larger viewing areas for high tilt tomography has had to do with the strength and durability of the plastic support films that are commercially available.

In the present study, we have also extensively trialed and employed a new “gridless” aperture/support film combination in which polyimide plastic support films (tested at thicknesses of 388 Å or 605 Å) span an “open aperture” of uniform 2 mm diameter (Luxel Corp., Friday Harbor, WA, USA). The polyimide support film was also tested at thicknesses of 388 Å, 400 Å, 552 Å, 605 Å and 741 Å using standard 1×2 mm slot grids. Most notably, the dramatically reduced shift/drift/charging we have been afforded through use of these “gridless”/open aperture supports (typically <0.8 pixel with successive measurements) in the EM at all tilts – in the absence of carbon coating - when compared to sections from the same specimen blocks prepared in parallel and imaged on regular formvar-coated slot grids carbon-coated both sides, provided us with (1) a significant improvement in efficiency (an overall 2–4-fold improvement in speed of tilt series acquisition) for semi-automated image data collection for ET and (2) the ability to reproducibly tilt to angles beyond 60° essentially regardless of the positioning of the ribbon(s) of serial sections. These factors played an important role in facilitating the rapid acquisition of tilt series data for an entire cell. Colloidal gold particles of 10 nm diameter were then deposited on both surfaces of these sections for use as fiducial markers during subsequent image alignment (Marsh et al., 2001b).

Whole cell tomography

Initially, over 40 serial thick sections through a well-preserved mouse islet were surveyed in 2D by stage-shifted montaging of 12×12 images at 4700× magnification using the data acquisition program SerialEM (Mastronarde, 2003; Mastronarde, 2005). These montages allowed us to identify a number of candidate cells for further study by whole cell ET and to determine how many sections each cell spanned. In addition, it allowed us to check what magnification and orientation were necessary to encompass each cell fully in cross-section within a single 2K × 2K CCD image (4K × 4K CCD, binned×2), and to check that sections were not damaged or contaminated in a way that would prevent potential ‘target’ cells from being imaged in toto.

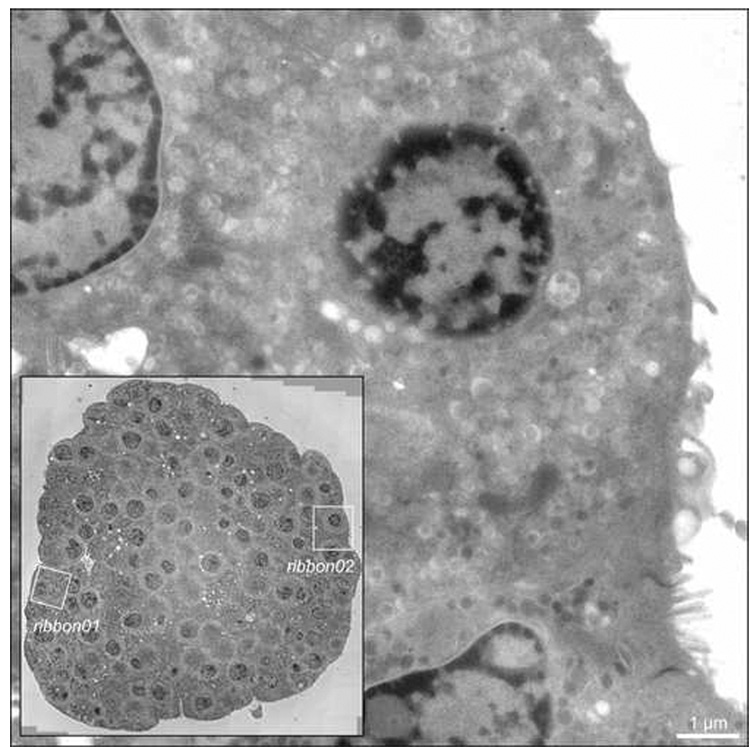

3D reconstruction by ET of each of the two beta cells (designated ‘ribbon01’ and ‘ribbon02’) was accomplished by single-axis tomography of 46 and 27 consecutive serial thick (300–400 nm) sections imaged at magnifications of 4700× or 3900×, respectively, using a Tecnai F30 intermediate voltage EM (FEI Company) and motorized tilt-rotate specimen holders (Models 650 and CT3500TR; GATAN Inc.) (Fig. 1). Tilt series data were digitally recorded using semi-automated methods for CCD (charge-coupled device) image montaging, data acquisition and image alignment as the sections were serially tilted by 2° increments over a range of ±62° using the microscope control program SerialEM. For ribbon01, a total of 46 adjacent serial thick sections were imaged at 4700× magnification (pixel size = 5.156 nm) to generate a final single volume spanning ~10×10×20 µm3 (Fig. 2A and Fig. 3). Tilt series image data for ribbon02 was collected in a similar manner from 27 serial thick sections (Fig. 2B and Fig. 4). However, because the cell was wider in X and Y, the magnification used in the tilt series was reduced down one step to 3900× (pixel size = 6.066 nm). The timecourse for tilt series data acquisition and reconstruction was between 2–3 weeks in total for each cell.

Fig. 1.

Intact islets of Langerhans isolated from adult mice were cultured overnight in vitro, stimulated with elevated extracellular glucose (11 mM) for 60 mins, and preserved for EM by high-pressure freezing, freeze-substitution and plastic embedding. Inset: 2D survey showing the whole islet in cross-section, acquired by stage-shifted montaging of 12×12 images at 4700× magnification using the data acquisition program SerialEM (Mastronarde, 2003; Mastronarde, 2005). Boxed regions highlight the two islet beta cells (designated ‘ribbon01’ and ‘ribbon02’) in the islet imaged and reconstructed by ET. Main image: 0° (untilted) view taken from one of the tilt series of islet beta cell ribbon02. Scale bar: 1 µm.

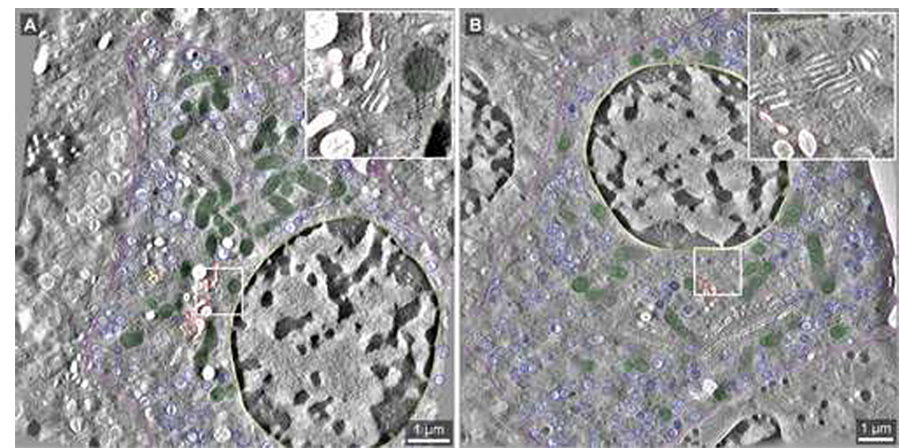

Fig. 2.

Tomographic slices extracted from the whole cell tomograms generated for datasets ribbon01 and ribbon02. The boxed areas reveal the relative membrane clarity for each of the two datasets at higher magnification (inset). A: Slice 939 of 2217 from the dataset ribbon01 (pixel size = 5.156 nm; imaged at 4700× magnification) shows segmentation of the Golgi ribbon (grey), TGN (red), mitochondria (green), mature insulin granules (dark blue), nucleus (yellow), and plasma membrane (purple). B: Slice 556 of 1153 from ribbon02 (pixel size = 6.066 nm; imaged at 3900× magnification). The color coding scheme is as described above for A. Scale bars: 1 µm.

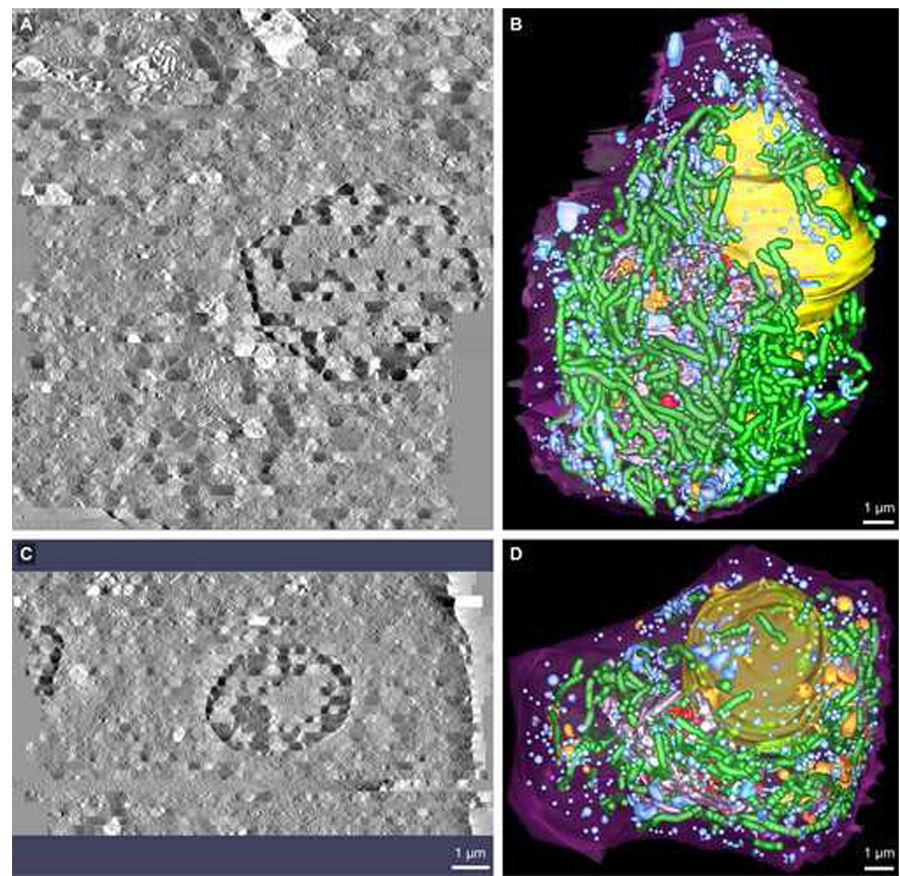

Fig. 3.

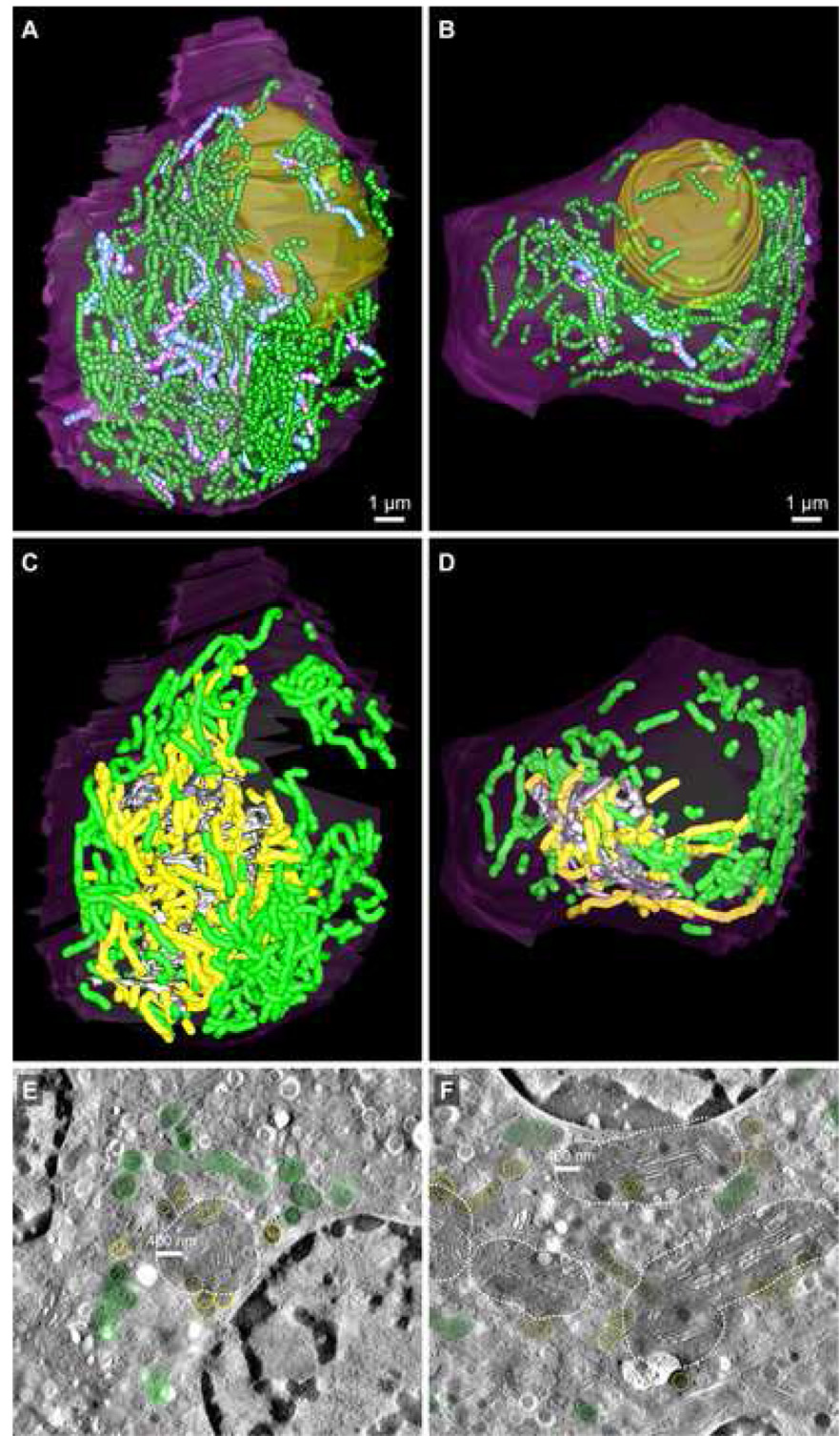

Comparison views along the X–Z axis of the surface-rendered 3D model data segmented following serial section ET reconstruction of ribbon01 and ribbon02. A & C: Tomographic volumes that encompassed each of the beta cells designated ribbon01 and ribbon02 were generated by joining 46 and 27 serial section tomograms, respectively. B & D: 3D models revealing key compartments involved in insulin production and release by beta cells were generated for each of ribbon01 and ribbon02 using an expedited segmentation approach that allowed for the efficient yet accurate mark-up of organelles such as the Golgi ribbon and TGN, mitochondria and insulin granules (both immature and mature). Here, however, the 3D model data are presented with the dark blue spheres demarking the mature insulin granule populations omitted so that the other compartments such as immature granules and multi-granular/vesicular bodies can be more readily seen (for detailed visualization of mature insulin granules, see Fig. 4). Shown is the: plasma membrane (purple), nucleus (yellow), main Golgi ribbon (grey), trans-most Golgi cisterna (red), penultimate trans-Golgi cisterna (gold), mitochondria (green), multi-vesicular bodies (orange) and immature granules (light blue). Scale bars: 1 µm.

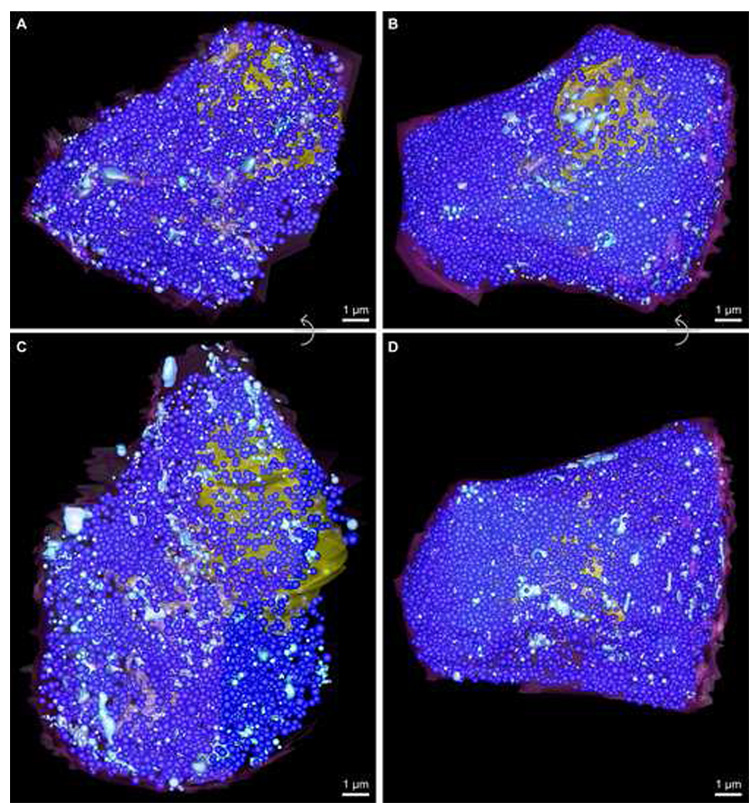

Fig. 4.

Figure panel showing the relative number and distribution of both mature and immature insulin granules in both beta cell reconstructions. Mature insulin granules are demarked as dark blue spheres, while immature secretory granules are colored light blue (for unobstructed views of the number and distribution of immature granule pools in each cell, see Fig. 3; due to the crowded appearance of the cytosol because of the numerous insulin granules, this figure panel is best viewed electronically). A and C show top and side views, respectively, for ribbon01, which contained 3370 mature insulin granules (average diameter 280 nm) and ~700 immature granules. Likewise, B and D reveal top and side views, respectively, for ribbon02, which contained 8250 mature insulin granules (average diameter 245 nm) and ~520 immature secretory granules. Scale bars: 1 µm.

Tilt series images (2K × 2K) acquired to an UltraScan™ 4000 (USC4000, Model 895; GATAN Inc.) were first brought into register with one another by cross-correlation. Tracking a limited number (~40) of the 10 nm gold fiducial markers on both surface(s) of the sections across the entire field of view became an absolute prerequisite so that the program TILTALIGN could be used to solve for global fiducial alignment and distortion correction. Fiducial-less alignment procedures generally resulted in grossly distorted and uninterpretable tomograms because of the significant and inherent geometrical changes and distortions across such large cellular areas. Tomograms from each of the serial sections through the cell(s) calculated by R-weighted backprojection from each set of aligned tilts were joined along the Z-axis essentially as described previously (Ladinsky et al., 1999; Marsh et al., 2001b; Shoop et al., 2002; Sosinsky et al., 2005) using the interactive program MIDAS to generate a general linear transform that accounted for rotation, translation and stretch of one section relative to its nearest neighbor. 3D cellular reconstructions generated in this way using the IMOD software package incorporating the eTomo and 3dmod graphical user interfaces were then analyzed (Kremer et al., 1996).

Segmentation and quantitative 3D analysis

Compartments/organelles within the tomographic volumes were segmented, extracted and viewed using IMOD software package (Kremer et al., 1996). To quantify membrane surface area and volume for the entire Golgi ribbon in each cell expeditiously (Fig. 6), only every third slice in Z was modeled for cis-medial cisternae (which were segmented/modeled as a single object) and likewise for trans-Golgi cisternae, the latter frequently/collectively referred to as the trans-Golgi network (TGN). In ribbon01, the penultimate trans-Golgi cisterna and trans-most Golgi cisterna were modeled as separate objects to demarcate functional exit sites along the length of the Golgi ribbon.

Fig. 6.

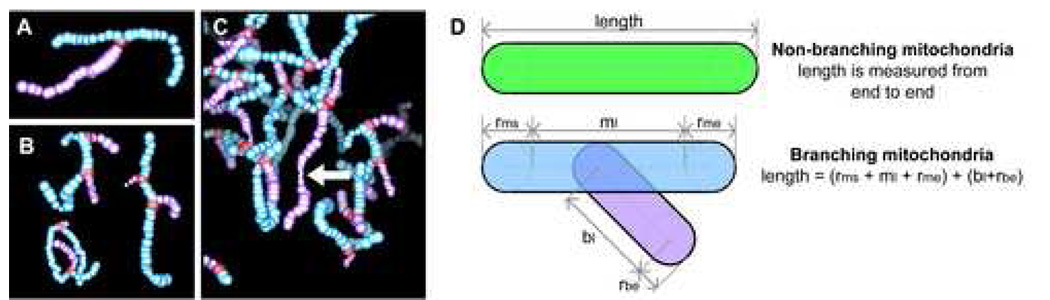

Variations in mitochondrial morphology are presented by way of example from ribbon01. As described in ‘Materials and Methods’, mitochondria were segmented using an abbreviated approach aimed at expediting analysis whilst still providing important and accurate quantitative information indicative of changes in mitochondrial structure-function relationships in situ. Consequently, both intra- and inter-cellular variations were quantified with regard to the extent of mitochondrial branching, length and diameter. For visual simplification, the main lengths of mitochondria are shown here in light blue, while branches are colored mauve so that they can be readily distinguished; mitochondrial branch points are highlighted in red. A–C: Representative examples are provided for either single (A) or multiple (B) mitochondrial branches, and for regions where the mitochondrial diameter thins dramatically (C), suggestive of active mitochondrion fission or fusion. D: A cartoon demonstrating how mitochondrial length and branching was assessed and measured.

The plasma cell membrane (purple) and nucleus (yellow) were delineated using only ~4 contours per section, but still provided a clear definitiion of their boundaries. Mitochondria were segmented by drawing a series of connected spheres centered along the length of each. In this way, we were able to mark-up all of the mitochondria in less than 15 hours per cell. The numerous mature granules (blue) were segmented by precisely fitting a sphere. However, for immature granules (light blue), approximately half were segmented as a sphere while those more irregular in shape were segmented using contours (~1 in every 6 slices), as were multi-vesicular compartments. All spheres - including those used to approximate mitochondria - were centered as accurately as possible and individually resized.

Spatial relationships (such as the proximity distribution analysis between mitochondria and the surface of the Golgi ribbon presented in Fig. 8) among the modeled objects in 3D were assessed and quantified essentially as described elsewhere using the program mtk (Marsh et al., 2001b). Because sections cut from plastic (epon) resin are known to collapse by ~40% in the EM on initial exposure to the electron beam (Luther et al., 1988), the 3D surface-rendered model data were re-expanded by a factor of 1.7 in Z to more accurately represent the original topology of subcellular structures under study in the plastic section prior to imaging in the EM (Marsh et al., 2001b). Membrane surface area and volumes were computed from the contours and triangular meshes essentially as described previously (Marsh et al., 2001a; Marsh et al., 2001b).

Fig. 8.

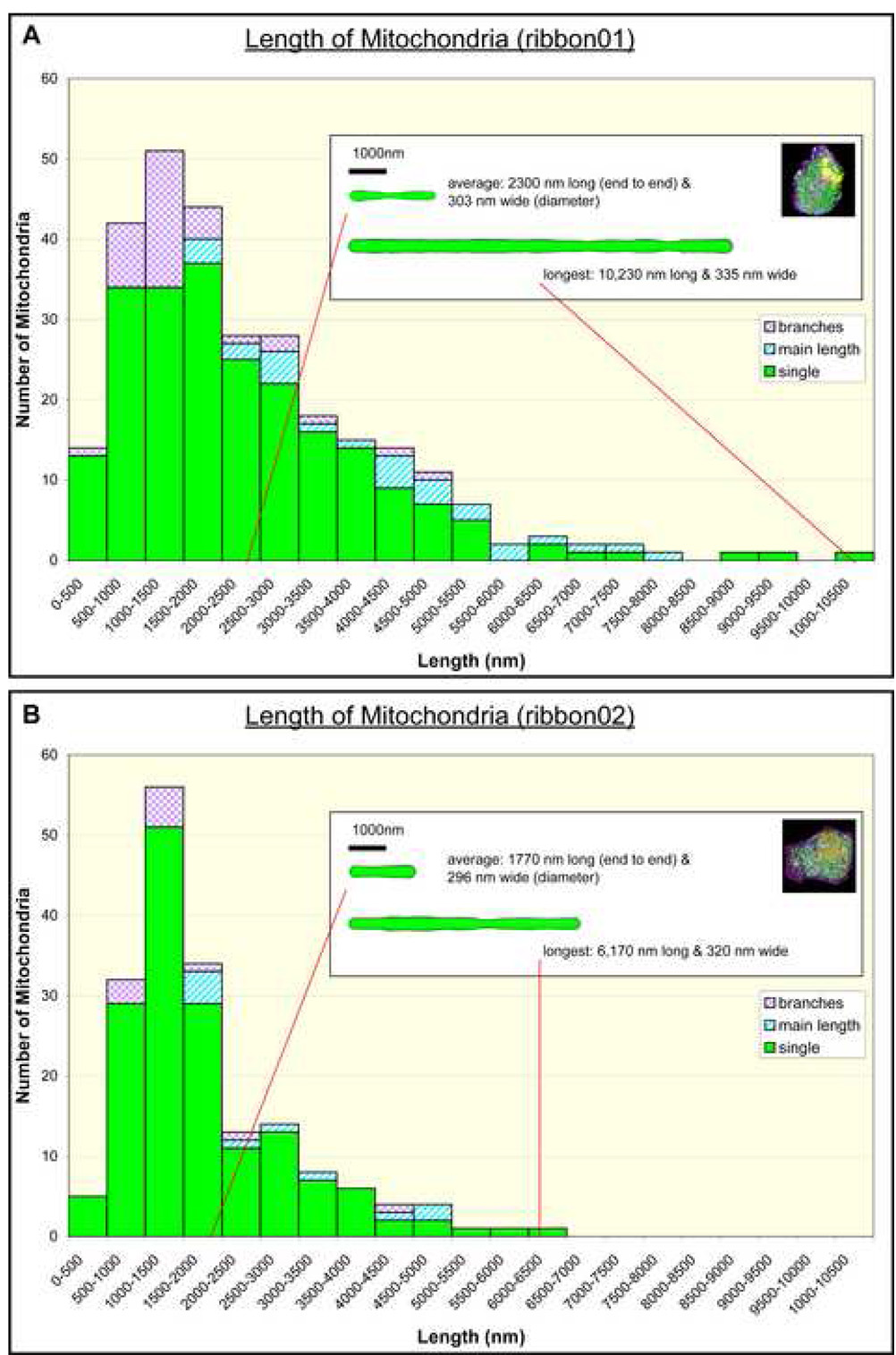

A comparative analysis of the variation in mitochondrial length between ribbon01 (A) and ribbon02 (B). Please note that the length of individual branches has been graphed separately to the main lengths of mitochondria; also see Table 2 for a summary of additional quantitative data related to branched versus non-branched mitochondria in ribbon01 versus ribbon02. Inset: The cartoon shows how the profile of a mitochondrion of average length compares to the longest mitochondrion measured for each cell if they were straightened.

Supplementary material and multimedia file generation

Additional figures and movies provided as supporting material for the data presented in Figure 1–Figure 8 accompany the online version of this article. Movies of the 3D data were compiled using Apple’s QuickTime® software from sequences of individual TIF files generated using the 3dmod viewer in IMOD, and files average around 10MB each in size. For videos of tomograms and/or overlaid model/segmentation contours, images were generated as the tomogram was advanced in Z. For movies of the 3D surface-rendered models generated from segmented tomographic data, 3D models were typically incrementally rotated 360° around the y- and/or x-axis to provide unambiguous views of the structures.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using the program ‘R’ (http://www.r-project.org) by unpaired Students t-test, where p <0.05 was considered significant.

Database deposition/accession information

Original EM tilt series image stacks, together with the resulting tomographic reconstructions and 3D surface-rendered model data associated with this work have been deposited in the Cell Centered Database (CCDB; http://ncmir.ucsd.edu/CCDB/) (Martone et al., 2002). Associated QuickTime® movies and high-resolution images derived from the tomograms and 3D rendered models published here are publicly available for download directly from the CCDB or from the Journal of Structural Biology website, or can be provided from the authors on CD-ROM or DVD-ROM on request.

RESULTS

Although cellular ET has now almost reached the status of a ‘mainstream’ research tool, much remains to be learned about how best to utilize this powerful technique to answer significant research questions in mammalian cell and molecular biology. In our case, we have to date avoided imaging our insulin-secreting beta cells at lower magnifications (and thus, lower resolutions) to accommodate larger cellular areas for analysis, because the bulk of our studies – like many in the 3D EM community – have relied heavily on working toward developing the capacity to simultaneously visualize both organelles and large macromolecular protein complexes, etc., together in situ in 3D within the same high-resolution tomograms, to bridge the resolution gap with molecular microscopy and x-ray crystallography (Marsh, 2006; Medalia et al., 2002; Nickell et al., 2006). However, single axis tomography of serial thick (1–2 µm) sections cut from mammalian cells and tissue has in the past proved extremely useful for bridging the resolution gap in the other direction: from cell-to-tissue (Soto et al., 1994; Wilson et al., 1992). Moreover, efforts to directly correlate EM data in 2D and/or 3D over a range of resolutions against image data from the light microscope (LM) (both live cell imaging and indirect immunofluorescence data) promise to emerge as increasingly important as we move toward developing a more “holistic” understanding of how changes at the molecular level manifest at the level of cell and/or tissue (Biel et al., 2003; Gaietta et al., 2006; Höög et al., 2007; Kurner et al., 2005; Medalia et al., 2007; Sosinsky et al., 2007).

3D reconstruction of whole islet cells at ~15–20 nm resolution – an acceptable compromise between information quality and efficiency?

Recently, in an effort to understand how basic changes in beta cell/islet physiology are reflected in terms of organelle number, size and distribution at the level of the whole cell – and to work toward a schema that would lend itself to a rapid, automated approach for the comparative analysis of multiple whole tissue cells in the future - we carried out serial sectioning/single-axis ET of two entire beta cells from the same pancreatic islet of Langerhans that allowed us to image, reconstruct and analyze key aspects of cellular organization in 3D on the timescale of weeks (Fig. 1). Moreover, because we undertook these studies of different cells within the same unit tissue but at different magnifications, it afforded us the opportunity to directly compare the quality of the data generated, to determine a ‘minimum’ magnification requirement for upcoming whole cell studies by ET (Fig. 2).

Although we initially aimed to use fiducial-less alignment for the rapid reconstruction of individual volumes for the 46 and 27 serial sections that were imaged for each of ribbon01 and ribbon02, respectively, it became apparent that we absolutely needed to track a small number (~40) of the fiducials to solve for global alignment so that distortion in the final tomograms was reduced to a point where the data were of sufficient quality for a robust and accurate analysis (Supplemental Data S1). However, at a magnification of 3900× used to image ribbon02, the 10 nm gold fiducials were often difficult to visualize and track. A combination of less accurate tracking of fiducial beads, together with a reduced magnification, resulted in final tomograms of noticeably lower clarity for ribbon02 when compared with ribbon01 (Fig. 2). Although the use of fiducial markers with a larger diameter (e.g. 15 nm) could circumvent some aspects of the difficulties we experienced with bead tracking at a magnification of 3900×, it is worth noting that at a magnification of 4700× we experienced almost no difficulties tracking the 10 nm colloidal gold particles. Since one of the aims of this study was to develop a schema that would promote efforts to work with the same cells/tissue across multiple scales/resolutions by ET, the use of fiducial gold beads of a single diameter (10 nm) amenable to tracking at both low and high magnification was preferred.

Although the quality of reconstructions was substantially worse than can be obtained with high-resolution dual-axis tomograms that we routinely collect at 20000× or higher magnification, we estimated that the final resolution was still in target range of ~15–20 nm. At this resolution, and despite limiting data collection to a single axis, we were still able to clearly see and identify most of the organelles that we typically study in our higher resolution tomograms (Marsh et al., 2004; Marsh et al., 2001b), with the notable exception of microtubules. By way of example, individual cisternae of the Golgi ribbon were easily distinguished in each slice (Fig. 2 inset), although segmenting them through Z was less trivial. As a consequence, we have more recently attempted to find sets of imaging parameters that would allow us to image whole mammalian cells by ET quickly yet maintaining sufficient resolution to adequately visualize and track microtubules (data not shown). To this end, we have collected data at a number of intermediate magnifications (e.g. 9400× and 12000×) in combination with limited tiling/montaging (necessary to capture entire cells in cross-section at these magnifications) and additional image binning (to expedite electronic data readout from the CCD). Unfortunately, however, we have not managed to identify imaging parameters that would facilitate tomographic reconstruction of mammalian cells in toto in a suitably rapid manner as well as provide sufficient detail to track microtubules reliably. Any potential benefits of data collection at the higher magnifications were lost as a consequence of over-binning the tilt series images in order to acquire the montaged data in a temporally practical manner. This notion is reinforced by an excellent recent study by Höög and co-workers that specifically focused on elucidating microtubule organization in whole (fission) yeast cells by ET, and required them to collect tilt series data with a pixel size of ~1.5 nm (Höög et al., 2007). This compares well with our own experience tracking microtubules reliably in high-resolution reconstructions with pixel sizes of ~2.5 nm or smaller. In our own trials outlined above, we were able to follow microtubules in single axis tomograms from data collected at 9400× magnification (binned×3; final pixel size of 3.94 nm) more easily than in dual-axis tomograms from tilt series collected at 12000× magnification (binned×4; final pixel size of 4.17 nm) (data not shown).

Although the effective resolution in Z was considerably (~1.7 times) worse than the resolution in X and Y, a more significant problem during segmentation resulted from misalignment of adjacent sections. Due to uneven specimen collapse in the EM together with heterogeneous section thinning and distortion during tilt series acquisition (Kremer et al., 1990; Luther et al., 1988; Marsh, 2005; van Marle et al., 1995), the anisotropic distortions from one section to the next made it impossible to perfectly align serial sections using uniform transformations (Fig. 3; Supplemental Data S2). This problem is primarily an inherent consequence of our abbreviated approach, since sectional misalignment has been negligible (less than a few nm) in our previous high-resolution ET studies where dual-axis tomograms have been joined from serial thick sections essentially without issue (Ladinsky et al., 1999; Marsh et al., 2001a; Marsh et al., 2001b; McEwen and Marko, 1999). Here, in our lower resolution reconstructions of cellular areas >10 µm2 in X and Y, the problem of anisotropic distortion of sections was greatly exacerbated due to the size of the areas captured and as a consequence of employing single rather than dual-axis ET data. For example, in ribbon02 many organelles are offset by up to 90 nm (~15 pixels) between adjacent section boundaries in the worst-case scenarios. For these poorly aligned sections, additional care had to be taken to track organelles reliably (Fig. 3; Supplemental Data S2). However, in most instances, the alignment of serial section tomograms was sufficiently accurate that even convoluted membrane-bound organelles, such as mitochondria and the Golgi ribbon, could be followed unambiguously for reliable segmentation over their entire length and in Z.

Abbreviated segmentation techniques for rapid insights into 3D cell biology

Over the past few years, many discussions have taken place in our group with regard to the potential merits of using a heavily abbreviated approach for the rapid segmentation of large cellular volumes. After all, even ‘stick and ball’ models of atomic structure convey vital clues about the structure-function characteristics of molecules. In the current study, we decided to trial an expedited scheme for the segmentation of different organelles/compartments of interest that would allow us to extract crucial spatial and volumetric information about those structures as fast as possible, without sacrificing important information regarding differences/changes in compartment morphology.

The development of tools for the expedited segmentation and analysis of complex 3D cellular data has mostly failed to keep pace with the development of data acquisition hardware and reconstruction software. As demonstrated here, an enormous volume of ET data (several hundred gigabytes of raw data encompassing several hundred µm3 of cellular volume) can now be acquired and reconstructed relatively quickly (i.e. 2–3 weeks), but methods for extracting useful spatial and quantitative information from such data have remained relatively slow. Normally, to extract valuable information regarding structure-function relationships for and among organelles, the tomogram is typically segmented manually to delineate cellular compartments; outlining objects of interest on every successive tomographic slice allows one to generate a ‘contour map’ of subcellular topology which is then converted into a high fidelity 3D meshed model. This process represents the major bottleneck in our ET ‘processing pipeline’ for cellular data as it typically takes weeks to months per tomogram. The 3.1×3.2×1.2 µm3 volume of part of the Golgi region in an insulin-secreting HIT-T15 cell reconstructed at ~5–7 nm resolution in a previous study (Marsh et al., 2001b) required approximately 9 months of manual segmentation followed by ~3 months of additional editing for detailed analysis. Although this represents one of the largest tomographic volumes reconstructed from a mammalian cell at comparatively high (~5 nm) resolution, the mean volume of a murine beta cell volume has been estimated at ~1400 µm3 (Dean, 1973). Taken together, this reiterates the need for a ‘multi-resolution’ approach to segmenting 3D cellular data that depends on the biological question at hand.

In the present study, we were able to readily segment most membrane-bound organelles of interest in both cells, with the notable exception of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), small vesicles and microtubules (Fig. 3 & Fig. 4; Supplemental Data S3). Although both beta cells were selected based on equivalent locations (Fig. 1 inset) on opposite sides at the periphery of the same pancreatic islet, their organization was quite different. Ribbon01 was ~610 µm3 in volume and had an estimated total surface area of 683 µm2, with less than 10% (~5.3%) of the total plasma membrane facing the ‘extra-islet space’ (Fig. 1 inset). In contrast, ribbon02 was ~698 µm3 in volume (1.14× larger than ribbon01), with a total surface area of ~490 µm2, of which a comparatively large proportion (~23%) of the plasma membrane faced the islet’s exterior (Fig. 1 inset; Supplemental Data S2).

Comparative quantification of insulin granule number, size and distribution

Each mature insulin granule was segmented by fitting and re-sizing a sphere that approximated its surface area and volume in 3D as described previously (Marsh et al., 2001b) (Fig. 4; Supplemental Data S3). Surprisingly, although ribbon01 and ribbon02 had similar cell volumes (~610 µm3 versus ~698 µm3), ribbon01 contained 2.4× fewer mature granules (3370 = 5.54 per µm3) than ribbon02 (8250 = 11.8 per µm3). In addition, the average diameter of individual granules was 1.14× larger in ribbon01 than in ribbon02 (mean diameters of 280 nm versus 245 nm, respectively) (Table 1). Consequently, although ribbon01 contained fewer mature granules, the cytoplasmic volume occupied by those (mature) granules was disproportionately large in ribbon01 (8.5%) compared to ribbon02 (14%), even though total granule number was significantly lower for ribbon01 (Table 1; Supplemental Data S5).

Table 1.

A comparative summary of quantitative data derived for insulin granules, multi-vesicular bodies and the Golgi ribbon in datasets ribbon01 and ribbon02

| ribbon01 | ribbon02 | |

|---|---|---|

| Mature granules: Total number | 3370 | 8250 |

| Mean diametera | 280 ± 0.84 nm | 245 ± 0.43 nm |

| Estimated total volume | 42.6 µm3 | 68.4 µm3 |

| Immature granules: Total number | 700 | 520 |

| Estimated total volume | 5.6 µm3 | 5.0 µm3 |

| Multi-vesicular bodies: Total number | 28 | 12 |

| Estimated total volume | 0.39 µm3 | 3.7 µm3 |

| Golgi: Estimated volume of main stack | 3.6 µm3 | 3.1 µm3 |

| Estimated volume of penultimate trans cisterna | 0.35 µm3 | NA |

| Estimated volume of trans-most cisterna | 1.9 µm3 | 0.53 µm3 |

| Estimated total volume | 5.8 µm3 | 3.7 µm3 |

| Estimated membrane SA of main Golgi ribbon b | 310 µm2 | 230 µm2 |

| Estimated membrane SA of penultimate trans cisterna | 13.4 µm2 | NA |

| Estimated membrane SA of trans-most cisterna | 52.7 µm2 | 30.4 µm2 |

| Estimated total membrane SA | 380 µm2 | 260 µm2 |

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM

Typically, islet beta cells each contain ~9000 mature granules (Dean, 1973; Olofsson et al., 2002; Rorsman and Renstrom, 2003), with an estimated half-life of ~3–5 days (Halban, 1991; Halban and Wollheim, 1980). Moreover, it’s predicted that beta cells secrete only 1–2% of their insulin granule content per hour under stimulatory conditions (Rorsman and Renstrom, 2003). Although we had not predicted such differences in mature granule number and size between beta cells within the same islet, evidence exists for functional heterogeneity at the level of an individual islet beta cell’s capacity to exocytose insulin granules in response to stimulation with elevated extracellular glucose (Bennett et al., 1996; Heimberg et al., 1993; Leung et al., 2005). Inversely, ribbon01 contained more (1.35×) immature insulin granules than ribbon02 (~700 versus ~520) (Supplemental Data S3). Multi-granular/-vesicular bodies – compartments of lysosomal origin that function in the intracellular degradation/dynamic turnover of ‘aged’ insulin granules - were more abundant (2.33×) in ribbon02 relative to ribbon01 (28 versus 12, respectively) (Bommer et al., 1976; Borg and Schnell, 1986; Halban, 1991; Halban and Wollheim, 1980; Halban et al., 1980; Halban et al., 1987; Orci et al., 1984) (Table 1; Supplemental Data S5).

Organization of the Golgi ribbon

The Golgi ribbon – assessed here in toto in 3D at ~15–20 nm resolution by ET for the first time in mammalian cells - exhibited a similar reticulated morphology overall in ribbon01 and ribbon02 (Fig. 5; Supplementary Data S3). In each case, the Golgi ribbon resembled a complex fenestrated structure in which the trans-face of the Golgi was oriented inward, while the cis-Golgi was usually oriented facing the plasma membrane. To expedite segmentation of the entire Golgi ribbon in each cell whilst still providing general information with regard to total membrane surface area and volume for the Golgi ribbon, the main stack - comprised of cis-medial cisternae (grey mesh; green model contours in the Fig. 5 inset) - was segmented as a single object using bounding polygons on every third tomographic slice. To more accurately calculate the approximate volume and surface area of the main Golgi ribbon, 50 slices in each cell were randomly selected and all cisternae were individually segmented (Fig. 5B inset) to provide a more accurate estimate of cisternal volume versus bounding volume and cisternae surface area versus bounding surface area. Thus, this ‘limited sampling’ approach helped guide and refine the accuracy of our measurements for the Golgi ribbon without requiring us to segment every individual cisterna.

Fig. 5.

The 3D organization of the entire Golgi ribbon was analysed in both glucose-stimulated islet beta cells reconstructed in toto. Membranes of the Golgi complex were segmented in ribbon01 (A) and ribbon02 (B) to distinguish between the main Golgi ribbon (i.e. the ‘ribbon proper’), comprised of stacked cis- and medial cisternae (grey), the trans-most Golgi cisterna (red) and the penultimate trans-cisterna (gold). The nucleus (yellow) is partially visible in the figure background for reference; the orientation of the Golgi relative to the cell is the same for ribbon01 and ribbon02 as for Fig. 3 and Fig. 4, respectively. B, inset: A portion of the segmented stacked cis-medial Golgi cisternae (highlighted in green) shows how the main Golgi ribbon was segmented.

In ribbon01, the Golgi had a total estimated volume (V) of approximately 5.8 µm3 and membrane surface area (SA) of 380 µm2 - calculated by summing together the main stack (V ≈ 3.6 µm3, SA ≈ 310 µm2), penultimate trans-cisterna (V ≈ 0.35 µm3, SA ≈ 13.4 µm2) and trans-most cisterna (V ≈ 1.9 µm3, SA ≈ 52.7 µm2). In contrast, in ribbon02 the Golgi ribbon comprised an estimated total volume of approximately 3.7 µm3 and membrane SA of 260 µm2–as calculated by summing together the main stack (V ≈ 3.1 µm3, SA ≈ 230 µm2) plus trans-most cisterna (V ≈ 0.53 µm3, SA ≈ 30.4 µm2). The penultimate Golgi in ribbon02 was not segmented separately from the main stacks/ribbon because it could not be identified reliably as was the case for ribbon01, both due to reduced resolution in ribbon02 and because the cisterna itself was ‘sparse’ (Table 1). Significantly, the Golgi ribbon accounted for almost twice (1.85×) the total non-nuclear/cytoplasmic cell volume in ribbon01 compared to ribbon02 (1.15% versus 0.62%, respectively).

Mitochondria: relating structure to function

In the present study, each mitochondrion was segmented by drawing a series of connected spheres along its length rather than our usual lengthy process of manually drawing contours tomographic slice by slice (Marsh et al., 2001b) (Supplemental Data S3 & Supplemental Data S4). For consistency, individual non-branched mitochondria as well as the main lengths of the branched mitochondria are colored light blue (Fig. 6 and Fig. 7A & B). For branched mitochondria, the branches themselves are colored mauve and the branch points have been highlighted in red (Fig. 6 and Fig. 7A & B). The main length was defined as the straightest path along the length of a given mitochondrion. However, it should be noted that sometimes the classification of main length versus branch(es) was arbitrary. For example, in Fig. 6A it is unclear exactly which portion of the mitochondrion could be considered the branch. Moreover, it remains somewhat open for debate whether these kinds of mitochondria should be considered as a single mitochondrion, two mitochondria in the process of fusion or fission, or three separate mitochondrial lengths (Chen and Chan, 2005; Frazier et al., 2006; Karbowski and Youle, 2003; Okamoto and Shaw, 2005; Perkins and Frey, 2000).

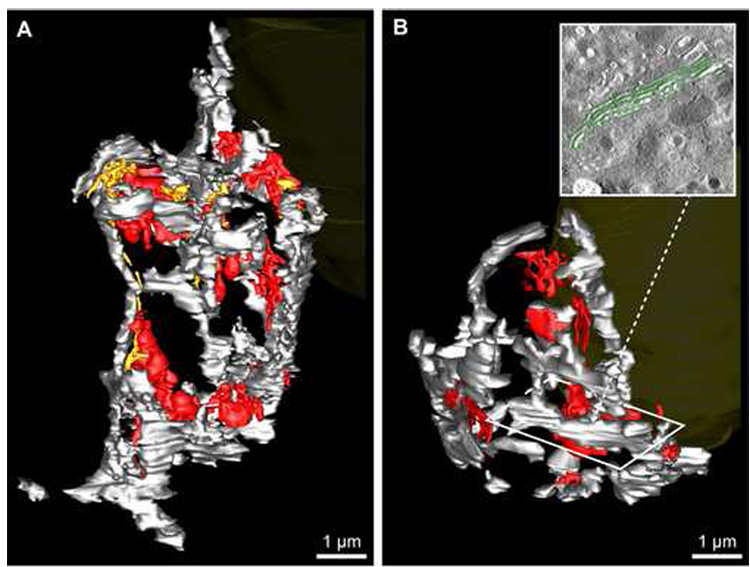

Fig. 7.

Mitochondrial organization and distribution in ribbon01 (A, C, E) and ribbon02 (B, D, F). A & B: The relative number and distribution of branched (main lengths: light blue; branches: mauve) versus non-branched (green) mitochondria are shown; branch points are highlighted with red spheres. Also refer to Table 2. Scale bars: 1 µm. C–F: A proximity-distribution analysis of mitochondria versus the Golgi ribbon was undertaken to assess relative differences in the extent of mitochondrial clustering to the Golgi between cells. C & D: The subset of mitochondria that came within an arbitrary (400 nm) zone of close approach to any surface of the Golgi ribbon are highlighted in yellow, while the remainder are colored green. E & F: Tomographic slices from ribbon01 (E) and ribbon02 (F) that show the arbitrary 400 nm proximity zone around the Golgi ribbon (shaded; dotted white line). The segmented Golgi (grey), proximal (yellow) and distal (green) mitochondria are visible. Scale bars: 400 nm.

Here, for the purposes of simplicity, we count the total number of mitochondria per cell as the number of single (unbranched) mitochondria (S) plus the number of main lengths (M) for the branched mitochondria. For a branched mitochondrion with n branches, we calculate its length as equal to the end-to-end length of the main length (m) end plus the length of all its branches (b1+ … +bn) (Fig. 6D).

A summary of quantitative data derived for mitochondria in ribbon01 and ribbon02 has been compiled in Table 2. In ribbon01, there were a total of 249 mitochondria, of which 10% had branches. Of the 26 branched mitochondria, most (17; 65%) had only a single branch (Fig. 6A); 8 (31%) had two branches (Fig. 6B) but only one (4%) had three branches. In ribbon02, there were 168 mitochondria, of which only 6% had branches. Of these 10 branched mitochondria, 9 had only a single branch while just one had two branches. The significant difference in the relative proportion of branched mitochondria per cell and the average number of branches per branched mitochondrion between the two cells suggests that the mitochondrial population in ribbon01 were more functionally active with a higher rate of fission/fusion than ribbon02 (Chen and Chan, 2005; Chen et al., 2005) (Table 2). Notably, the average cumulative length of branched mitochondria was considerably greater than that of non-branched mitochondria for both cells (2.5× versus 3.7× for ribbon01 and ribbon02, respectively), consistent with the idea that shorter (single) mitochondria are more stable and less likely to be involved in fusion/fission events, whereas longer (branched) mitochondria provide a greater surface where they can potentially form new branches or merge/fuse with other mitochondria (Chen et al., 2005) (Fig. 8). It is also noteworthy that the length of branched as well as non-branched mitochondria was significantly greater for ribbon01 than ribbon02 (1.35× versus 1.97×), suggesting that the increased proportion of branched mitochondria in ribbon01 itself does not account for the difference in mitochondrial length between the two cells (Fig. 8; Table 2; Supplemental Data S4).

Table 2.

A comparative summary of quantitative data derived for mitochondria in ribbon01 and ribbon02

| ribbon01 | ribbon02 | |

|---|---|---|

| Total number of mitochondria | 249 | 168 |

| Number of branched mitochondria | 26 (10%) | 10 (6%) |

| Mean number of branches per branched mitochondria | 1.38 | 1.1 |

| Mean length of non-branched mitochondria a,b | 2300 ± 107 nm | 1170 ± 86 nm |

| Mean diameter of non-branched mitochondria | 304 ± 2.8 nm | 296 ± 3.18 nm |

| Mean length of branched mitochondria | 5870 ± 468 nm | 4320 ± 635 nm |

| Mean diameter of branched mitochondria | 297 ± 4.0 nm | 280 ± 7.2 nm |

| Estimated total volume of all mitochondria | 49 µm3 | 21 µm3 |

| Estimated membrane SA of all mitochondria | 635 µm2 | 301 µm2 |

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM

indicates a significant difference in the length of branched mitochondria in ribbon01 versus ribbon02 (p < 0.0005)

As noted elsewhere and above, mitochondria are in a constant state of dynamic flux between fusion and fission events, with mitochondrial respiration and metabolism spatially and temporally regulated by the morphology and positioning of the organelle (Chen et al., 2005; McBride et al., 2006). With its increased proportion of branching mitochondria and presumably increased incidence of fission/fusion, ribbon01 provided us with a number of opportunities to identify sites along the lengths of mitochondria that thinned considerably – and tentatively represent static ‘snapshots’ of such events (Fig. 6C).

The global organization of mitochondria within each of the cells was itself quite striking (Fig. 7; Supplemental Data S4). In ribbon01, a large proportion of the mitochondria were closely apposed to the Golgi ribbon; 95 (~38%) of all mitochondria in the cell clustered within 400 nm of the Golgi (Fig. 7C & E; Supplemental Data S4), despite the fact that this space only accounts for ~14% of the cytoplasmic volume. In comparison, in ribbon02, only 35 (~20%) mitochondria approached within 400 nm of the Golgi ribbon (Fig. 7D & F; Supplemental Data S4).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we have employed methods for efficient tomographic reconstruction and analysis of whole cells to compare structure-function relationships between two ‘equivalent’ insulin-secreting beta cells (designated ‘ribbon01’ and ‘ribbon02’) that were similar in size (~610 µm3 and ~698 µm3, respectively) and located at comparable positions at the periphery of an (intact) isolated mouse islet of Langerhans. This was important, since functional heterogeneity in terms of responsiveness to stimulation with elevated extracellular glucose as well as capacity for the rapid exocytic release of insulin granules has been reported for beta cells of different sizes and/or positions within the same pancreatic islet (Leung et al., 2005; Rocheleau et al., 2004).

Collectively, our data demonstrating the relative differences between the two cells in terms of the number, dimensions and distribution of insulin granules, mitochondria and the Golgi strongly suggest inverse relationships among these organelles depending on the level of biosynthetic activity within the cell. Moreover, our data provide structure-function evidence that upon comparison of the two cells, ribbon01 represents a beta cell that has responded more vigorously to glucose-stimulation and appears to have discharged a large proportion (>60%) of its intracellular insulin granule stores (based on previous estimates of islet beta cell granule content) (Dean, 1973; Olofsson et al., 2002; Rorsman and Renstrom, 2003). Conversely, ribbon02 appears to have discharged <10% of its total insulin granule stores.

In addition, it is important to note that insulin secreted from the beta cell is rapidly replaced due to a specific glucose-induced increase in (pro)insulin biosynthesis (Rhodes, 2004). Typically, i.e. following short-term glucose stimulation (<4 hours), (pro)insulin synthesis occurs exclusively at the translational level (Wicksteed et al., 2003). Indeed, the fact that the threshold glucose concentration required to stimulate (pro)insulin biosynthesis (2–4 mM) is lower than that required to stimulate insulin granule exocytosis (4–6 mM) ensures that insulin production is maintained under conditions where insulin secretion is negligible (Ashcroft, 1980), and promotes the beta cell’s bias towards continual replenishment of its insulin stores (Ashcroft, 1980; Rhodes, 2004). Notably, the ratio of mature : immature granules was approximately 5:1 and 16:1 for ribbon01 and ribbon02, respectively.

Here, taken together with our finding that the intracellular granule pool in ribbon01 appears substantially depleted compared to ribbon02, the marked increase between the two cells in terms of the difference in Golgi volume/membrane surface area (5.8 µm3; 380 µm2 versus 3.7 µm3; 260µm2), particularly with respect to trans-Golgi cisternae alone (2.25 µm3; 66.1 µm2 versus 0.53 µm3; 30.4 µm2) (Supplemental Data S5), strongly indicated an upregulation of protein biosynthetic activity in ribbon01. Likewise, the relative increases in mitochondrial number, length, extent of branching as well as the proportion of mitochondria that were clustered in close proximity to the Golgi ribbon in ribbon01 compared to ribbon02 were all commensurate with an increased level of mitochondrial function/activity in response to additional energy demands stemming from elevated (pro)insulin biosynthesis (Fig. 8; Supplemental Data S5). Indeed, in ribbon01 mitochondria accounted for 8.0% (2.2× more) of the cytoplasmic volume compared with 3.6% in ribbon02 (see Supplemental Data S5).

Finally - consistent with the idea that regulated secretory cells such as the beta cells of the endocrine pancreas must dynamically regulate the balance between the biosynthesis of new insulin granules versus the exocytic/extracellular release of insulin or the intracellular digestion of older granules (Bommer et al., 1976; Borg and Schnell, 1986; Halban, 1991; Halban and Wollheim, 1980; Halban et al., 1980; Halban et al., 1987; Orci et al., 1984) to ensure that cellular insulin stores are maintained at appropriate levels - it is noteworthy that the number of identifiable degradative compartments in ribbon02 is more than 2-fold greater than ribbon01 (Supplemental Data S5) . Also consistent with the notion that ribbon02 housed a ‘more mature’ granule population was our finding that the average diameter of insulin granules was smaller in ribbon02 than in ribbon01 (245 nm versus 280 nm), since it has been reported elsewhere that insulin granules shrink as they age (Hutton, 1989).

Taken together, our data suggest that ribbon01 had discharged the bulk of its insulin granule stores in response to stimulation with extracellular glucose and was in the throes of preparing for subsequent rounds of new insulin granule production at the time the islet was frozen. In contrast, ribbon02 appeared not to have responded strongly to the glucose stimulus prior to islet freezing, with its Golgi ribbon and mitochondrial population apparently maintained under steady-state conditions.

CONCLUSIONS

We have successfully developed an expedited approach (on a timescale of weeks rather than months) that has allowed us to reconstruct and view mammalian cells in detail (at ~15–20 nm resolution) in their entirety in 3D by ET. In parallel, we have developed/applied a number of abbreviated segmentation techniques that have enabled us to extract useful quantitative and spatial information regarding structure-function relationships of organelles at a cellular level on a timescale of months rather than years. Taken together, these approaches for the efficient 3D reconstruction and analysis of whole mammalian cells provide us with a set of tools that – although comparatively crude relative to conventional methods for subcellular tomography – offer a level of insight into the complex 3D organization of mammalian cells not currently afforded by other techniques. Notably, these methods are not intended to replace high-resolution ET approaches that yield 3D cellular information at approximately 5 nm resolution or better, but with concomitant demands on time and resources.

That said, we continue to explore a number of options for improving the accuracy of quantitative data obtained from future cellular reconstructions, but with the aim of maintaining a compromise between the efficiency of whole cell tomographic data collection and resolution (Marsh, 2005). First, to improve isotropy whilst minimizing the strength of noise artifacts that originate from data collected around a single-axis, we propose to assess the contribution of a limited set of tilts from a second tilt series orthogonal to the first (Mastronarde, 1997; Penczek et al., 1995). Second, to minimize the extent to which errors accumulate as a consequence of using uniform transforms to align volumes generated from large sections, we are currently testing methods for non-uniform distortion and alignment of serial volumes. Third, we are developing additional tools to compensate for missing material that typically occurs at the top and bottom of tomograms following 3D reconstruction through the addition of ‘ghost’ tomographic slices to substitute for missing cellular volume. Finally, we are working to implement a number of ‘smart’ yet interactive interpolative tools that will offer both improved speed and accuracy for segmentation on a day-to-day basis.

Supplementary Material

Three separate QuickTime® movies that show fiducial-less reconstructions generated from one of the section volumes for direct comparison against a reconstruction of the same tilt series data generated by fine alignment/global distortion correction using only 40 fiducial markers are presented. In S1_Fiducial01.mov, both low and high zoom views of a selected subset of slices from the fiducial-less reconstruction (left) can be compared side by side with the matched subset of slices from the fiducially aligned tomogram (right) of the same data. In particular, attention should be drawn to the differences in clarity of membrane-bound structures and fiducial beads in the high zoom view from each tomogram. In S1_Fiducial02.mov, the entire range of tomographic slices is presented from the fiducial-less reconstruction at high zoom to demonstrate the patterns of distortion that can most clearly be seen in slices at the top and bottom of the reconstruction. S1_Fiducial03.mov shows the entire tomogram from the fiducially aligned data for comparison/evaluation with S1_Fiducial02.mov.

QuickTime® movies revealing the complete cellular volumes for ribbon01 and ribbon02 viewed after serial section ET reconstruction using 46 and 27 serial tomograms (S2_ribbon01_reconstruct.mov and S2_ribbon02_reconstruct.mov, respectively). Separate movies of the cellular reconstructions ribbon01 and ribbon02 that show some of the model contours generated during segmentation of the compartments defined in Fig. 3 are presented as S2_ribbon01_contours.mov and S2_ribbon01_contours.mov

QuickTime® movie (S3_ribbon01_whole_cell.mov) showing the 3D model of the whole-cell reconstruction of the beta cell ribbon01. The first quarter of the movie illustrates the apparent crowdedness of the cytoplasm, in this case due primarily to the large number of mature granules (dark blue), immature granules (light blue) and mitochondria. The second quarter of the movie showcases the complex fenestrated structure of the main Golgi stack (grey), penultimate trans-Golgi cisterna (gold) and trans-most Golgi cisterna (red). Consistent with our previous studies with insulin-secreting cell lines (Marsh et al., 2001a; Marsh et al., 2001b), the exit sites/trans-face of the Golgi stacks are oriented ‘inwards’ rather than toward the cell surface. The second half of the movie provides a close-up view of the snake-like mitochondria (green), which cluster close to the Golgi ribbon.

QuickTime® movie (S4_Mitochondria.mov) showing a comparison between the mitochondria in beta cell ribbon01 (left) and ribbon02 (right). The first half of the movie highlights the differences between the two cells with regard to the number and distribution of branched mitochondria, colored light blue (for the main length) and purple (for the branches) with red spheres identifying branch points. Note that branched mitochondria are significantly (p < 0.0005) longer and more numerous in ribbon01 versus ribbon02. The second half of the movie highlights the subset of mitochondria closest to the Golgi. Mitochondria that approached within 400 nm of the surface of the Golgi ribbon are shown in yellow, the rest in green. Notice many of the mitochondria in ribbon02 also crowd against the far right side of the cell (opposite the Golgi ribbon), which represents the plasma membrane open to the extra-islet space. Both cells are shown at the same scale.

A graphical breakdown of the relative contributions for each of the compartments segmented in this study (the Golgi, nucleus, mitochondria, insulin granules, multi-vesicular compartments) with respect to total cell volume. Relative differences between ribbon01 (A) and ribbon02 (B) are highlighted in red. The category ‘other’ for both cells comprises that portion of the cell volume not included within the boundaries of that subset of cellular compartments/organelles listed above that were segmented in our analysis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Pamela Hollis from the Luxel Corporation (Friday Harbor, WA, USA), who has orchestrated collaborative support in the form of provision and quality control of new specimen supports for testing for cryo-EM and ET. This work was supported by an Australian Postgraduate Award (APA) scholarship to ABN, and grants from the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation International (2-2004-275) and the National Institutes of Health (DK-71236) to BJM. BJM is a Senior Research Affiliate of the ARC Special Research Centre for Functional and Applied Genomics. The Advanced Cryo-Electron Microscopy Laboratory housed at the Institute for Molecular Bioscience is a major node of the National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy-funded ‘National Facility for Advanced Microscopy and Microanalysis’, and is jointly supported by the Queensland State government’s ‘Smart State Strategy’ initiative. We thank nanoTechnology Systems (Greensborough, VIC, Australia) for critical maintenance and upgrades of the 300 keV Tecnai F30 EM within the laboratory. The Cell Centered Database (CCDB) is supported by NIH grants from NCRR RR04050, RR RR08605 and the Human Brain Project DA016602 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering and the National Institute of Mental Health. Finally, we sincerely thank the three anonymous reviewers for their time and constructive criticisms that led to an improved final manuscript.

Abbreviations

- 3D

three dimensions/-dimensional

- 2D

two-dimensions/-dimensional

- EM

electron microscope/microscopy/microscopic

- ET

electron microscope tomography

- TGN

trans-Golgi network

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- keV

kilo electron volts

- NCS

newborn calf serum

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- LM

light microscope/microscopy/microscopic

- SA

surface area

- V

volume

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Arita M, Robert M, Tomita M. All systems go: launching cell simulation fueled by integrated experimental biology data. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2005;16:344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft SJ. Glucoreceptor mechanisms and the control of insulin release and biosynthesis. Diabetologia. 1980;18:5–15. doi: 10.1007/BF01228295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett BD, Jetton TL, Ying G, Magnuson MA, Piston DW. Quantitative subcellular imaging of glucose metabolism within intact pancreatic islets. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3647–3651. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.7.3647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biel SS, Kawaschinski K, Wittern KP, Hintze U, Wepf R. From tissue to cellular ultrastructure: closing the gap between micro- and nanostructural imaging. J Microsc. 2003;212:91–99. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2818.2003.01227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bommer G, Schafer HJ, Kloppel G. Morphologic effects of diazoxide and diphenylhydantoin on insulin secretion and biosynthesis in B cells of mice. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol. 1976;371:227–241. doi: 10.1007/BF00433070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner-Weir S. Morphological evidence for pancreatic polarity of beta-cell within islets of Langerhans. Diabetes. 1988;37:616–621. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.5.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner-Weir S. Pancreatic islets: morphology, organization, and physiological implications. In: Draznin B, et al., editors. Molecular and Cellular Biology of Diabetes Mellitus. New York: Alan. R. Liss, Inc.; 1989. pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Bonner-Weir S, Orci L. New perspectives on the microvasculature of the islets of Langerhans in the rat. Diabetes. 1982;31:883–889. doi: 10.2337/diab.31.10.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borg LA, Schnell AH. Lysosomes and pancreatic islet function: intracellular insulin degradation and lysosomal transformations. Diabetes Res. 1986;3:277–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bork P, Serrano L. Towards cellular systems in 4D. Cell. 2005;121:507–509. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrage K, Hood L, Ragan MA. Advanced computing for systems biology. Brief Bioinform. 2006;7:390–398. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbl033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Chan DC. Emerging functions of mammalian mitochondrial fusion and fission. Hum Mol Genet 14 Spec No. 2. 2005:R283–R289. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Chomyn A, Chan DC. Disruption of fusion results in mitochondrial heterogeneity and dysfunction. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:26185–26192. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503062200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coggan JS, Bartol TM, Esquenazi E, Stiles JR, Lamont S, Martone ME, Berg DK, Ellisman MH, Sejnowski TJ. Evidence for ectopic neurotransmission at a neuronal synapse. Science. 2005;309:446–451. doi: 10.1126/science.1108239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean PM. Ultrastructural morphometry of the pancreatic b-cell. Diabetologia. 1973;9:115–119. doi: 10.1007/BF01230690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egner A, Verrier S, Goroshkov A, Soling HD, Hell SW. 4Pi-microscopy of the Golgi apparatus in live mammalian cells. J Struct Biol. 2004;147:70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier AE, Kiu C, Stojanovski D, Hoogenraad NJ, Ryan MT. Mitochondrial morphology and distribution in mammalian cells. Biol Chem. 2006;387:1551–1558. doi: 10.1515/BC.2006.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaietta GM, Giepmans BN, Deerinck TJ, Smith WB, Ngan L, Llopis J, Adams SR, Tsien RY, Ellisman MH. Golgi twins in late mitosis revealed by genetically encoded tags for live cell imaging and correlated electron microscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17777–17782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608509103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotoh M, Maki T, Kiyoizumi T, Satomi S, Monaco AP. An improved method for isolation of mouse pancreatic islets. Transplantation. 1985;40:437–438. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198510000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greider MH, Howell SL, Lacy PE. Isolation and properties of secretory granules from rat islets of Langerhans. II. Ultrastructure of the beta granule. J Cell Biol. 1969;41:162–166. doi: 10.1083/jcb.41.1.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halban PA. Structural domains and molecular lifestyles of insulin and its precursors in the pancreatic beta cell. Diabetologia. 1991;34:767–778. doi: 10.1007/BF00408349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halban PA, Wollheim CB. Intracellular degradation of insulin stores by rat pancreatic islets in vitro. An alternative pathway for homeostasis of pancreatic insulin content. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:6003–6006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halban PA, Wollheim CB, Blondel B, Renold AE. Long-term exposure of isolated pancreatic islets to mannoheptulose: evidence for insulin degradation in the beta cell. Biochem Pharmacol. 1980;29:2625–2633. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(80)90077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halban PA, Mutkoski R, Dodson G, Orci L. Resistance of the insulin crystal to lysosomal proteases: implications for pancreatic B-cell crinophagy. Diabetologia. 1987;30:348–353. doi: 10.1007/BF00299029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara M, Dizon RF, Glick BS, Lee CS, Kaestner KH, Piston DW, Bindokas VP. Imaging pancreatic beta-cells in the intact pancreas. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;290:E1041–E1047. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00365.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimberg H, De Vos A, Vandercammen A, Van Schaftingen E, Pipeleers D, Schuit F. Heterogeneity in glucose sensitivity among pancreatic beta-cells is correlated to differences in glucose phosphorylation rather than glucose transport. Embo J. 1993;12:2873–2879. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05949.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höög JL, Schwartz C, Noon AT, O'Toole ET, Mastronarde DN, McIntosh JR, Antony C. Organization of interphase microtubules in fission yeast analyzed by electron tomography. Dev Cell. 2007;12:349–361. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell SL, Tyhurst M. Cryo-ultramicrotomy of islets of Langerhans. Some observations on the fine structure of mammalian islets in frozen sections. J Cell Sci. 1974;15:591–603. doi: 10.1242/jcs.15.3.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell SL, Kostianovsky M, Lacy PE. Beta granule formation in isolated islets of langerhans: a study by electron microscopic radioautography. J Cell Biol. 1969;42:695–705. doi: 10.1083/jcb.42.3.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton JC. The insulin secretory granule. Diabetologia. 1989;32:271–281. doi: 10.1007/BF00265542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karbowski M, Youle RJ. Dynamics of mitochondrial morphology in healthy cells and during apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:870–880. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer JR, Mastronarde DN, McIntosh JR. Computer visualization of three-dimensional image data using IMOD. J Struct Biol. 1996;116:71–76. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer JR, O'Toole ET, Wray GP, Mastronarde DN, Mitchell SJ, McIntosh JR. Characterization of beam-induced thinning and shrinkage of semi-thick sections in the HVEM; Proc. XII Int. Congr. Electr. Microsc., Vol. 3; 1990. pp. 752–753. [Google Scholar]

- Kurner J, Frangakis AS, Baumeister W. Cryo-electron tomography reveals the cytoskeletal structure of Spiroplasma melliferum. Science. 2005;307:436–438. doi: 10.1126/science.1104031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladinsky MS, Mastronarde DN, McIntosh JR, Howell KE, Staehelin LA. Golgi structure in three dimensions: functional insights from the normal rat kidney cell. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:1135–1149. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.6.1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehner B, Tischler J, Fraser AG. Systems biology: where it's at in 2005. Genome Biol. 2005;6:338. doi: 10.1186/gb-2005-6-8-338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung YM, Ahmed I, Sheu L, Tsushima RG, Diamant NE, Hara M, Gaisano HY. Electrophysiological characterization of pancreatic islet cells in the mouse insulin promoter-green fluorescent protein mouse. Endocrinology. 2005;146:4766–4775. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luther PK, Lawrence MC, Crowther RA. A method for monitoring the collapse of plastic sections as a function of electron dose. Ultramicroscopy. 1988;24:7–18. doi: 10.1016/0304-3991(88)90322-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Bindokas VP, Kuznetsov A, Rhodes C, Hays L, Edwardson JM, Ueda K, Steiner DF, Philipson LH. Direct imaging shows that insulin granule exocytosis occurs by complete vesicle fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9266–9271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403201101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh BJ. Lessons from tomographic studies of the mammalian Golgi. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1744:273–292. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh BJ. Toward a "Visible Cell"… and beyond. Australian Biochemist. 2006;37:5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh BJ. Reconstructing mammalian membrane architecture by large area cellular tomography. Methods Cell Biol. 2007;79C:193–220. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(06)79008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh BJ, Mastronarde DN, McIntosh JR, Howell KE. Structural evidence for multiple transport mechanisms through the Golgi in the pancreatic beta-cell line, HIT-T15. Biochem Soc Trans. 2001a;29:461–467. doi: 10.1042/bst0290461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh BJ, Volkmann N, McIntosh JR, Howell KE. Direct continuities between cisternae at different levels of the Golgi complex in glucose-stimulated mouse islet beta cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:5565–5570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401242101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh BJ, Mastronarde DN, Buttle KF, Howell KE, McIntosh JR. Organellar relationships in the Golgi region of the pancreatic beta cell line, HIT-T15, visualized by high resolution electron tomography. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001b;98:2399–2406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051631998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martone ME, Gupta A, Wong M, Qian X, Sosinsky G, Ludascher B, Ellisman MH. A cell-centered database for electron tomographic data. J Struct Biol. 2002;138:145–155. doi: 10.1016/s1047-8477(02)00006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastronarde DN. Dual-axis tomography: an approach with alignment methods that preserve resolution. J Struct Biol. 1997;120:343–352. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1997.3919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastronarde DN. SerialEM: A program for automated tilt series acquisition on Tecnai microscopes using prediction of specimen position. Microsc Microanal. 2003;9:1182–1183. [Google Scholar]

- Mastronarde DN. Automated electron microscope tomography using robust prediction of specimen movements. J Struct Biol. 2005;152:36–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride HM, Neuspiel M, Wasiak S. Mitochondria: more than just a powerhouse. Curr Biol. 2006;16:R551–R560. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BF, Marko M. Three-dimensional transmission electron microscopy and its application to mitosis research. Methods Cell Biol. 1999;61:81–111. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61976-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medalia O, Weber I, Frangakis AS, Nicastro D, Gerisch G, Baumeister W. Macromolecular architecture in eukaryotic cells visualized by cryoelectron tomography. Science. 2002;298:1209–1213. doi: 10.1126/science.1076184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medalia O, Beck M, Ecke M, Weber I, Neujahr R, Baumeister W, Gerisch G. Organization of actin networks in intact filopodia. Curr Biol. 2007;17:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael DJ, Geng X, Cawley NX, Loh YP, Rhodes CJ, Drain P, Chow RH. Fluorescent cargo proteins in pancreatic beta-cells: design determines secretion kinetics at exocytosis. Biophys J. 2004;87:L03–L05. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.052175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogelsvang S, Marsh BJ, Ladinsky MS, Howell KE. Predicting function from structure: 3D structure studies of the mammalian Golgi complex. Traffic. 2004;5:338–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9219.2004.00186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickell S, Kofler C, Leis AP, Baumeister W. A visual approach to proteomics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:225–230. doi: 10.1038/nrm1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolls MR, Coulombe M, Beilke J, Gelhaus HC, Gill RG. CD4-dependent generation of dominant transplantation tolerance induced by simultaneous perturbation of CD154 and LFA-1 pathways. J Immunol. 2002;169:4831–4839. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.4831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto K, Shaw JM. Mitochondrial morphology and dynamics in yeast and multicellular eukaryotes. Annu Rev Genet. 2005;39:503–536. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.093019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olofsson CS, Gopel SO, Barg S, Galvanovskis J, Ma X, Salehi A, Rorsman P, Eliasson L. Fast insulin secretion reflects exocytosis of docked granules in mouse pancreatic B-cells. Pflugers Arch. 2002;444:43–51. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0781-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orci L. A portrait of the pancreatic B-cell. The Minkowski Award Lecture delivered on July 19, 1973, during the 8th Congress of the International Diabetes Federation, held in Brussels, Belgium. Diabetologia. 1974;10:163–187. doi: 10.1007/BF00423031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orci L. The microanatomy of the islets of Langerhans. Metabolism. 1976a;25:1303–1013. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(76)80129-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orci L. Some aspects of the morphology of insulin-secreting cells. Acta Histochem. 1976b;55:147–158. doi: 10.1016/S0065-1281(76)80103-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orci L. The insulin factory: a tour of the plant surroundings and a visit to the assembly line. The Minkowski lecture 1973 revisited. Diabetologia. 1985;28:528–546. doi: 10.1007/BF00281987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orci L, Ravazzola M, Amherdt M, Yanaihara C, Yanaihara N, Halban P, Renold AE, Perrelet A. Insulin, not C-peptide (proinsulin), is present in crinophagic bodies of the pancreatic B-cell. J Cell Biol. 1984;98:222–228. doi: 10.1083/jcb.98.1.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penczek P, Marko M, Buttle K, Frank J. Double-tilt electron tomography. Ultramicroscopy. 1995;60:393–410. doi: 10.1016/0304-3991(95)00078-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins GA, Frey TG. Recent structural insight into mitochondria gained by microscopy. Micron. 2000;31:97–111. doi: 10.1016/s0968-4328(99)00065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes CJ. Processing the insulin molecule. In: LeRoith D, et al., editors. Diabetes Mellitus. A Fundemental and Clinical Text. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 2004. pp. 27–50. [Google Scholar]

- Rocheleau JV, Walker GM, Head WS, McGuinness OP, Piston DW. Microfluidic glucose stimulation reveals limited coordination of intracellular Ca2+ activity oscillations in pancreatic islets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:12899–12903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405149101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorsman P, Renstrom E. Insulin granule dynamics in pancreatic beta cells. Diabetologia. 2003;46:1029–1045. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1153-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoop RD, Esquenazi E, Yamada N, Ellisman MH, Berg DK. Ultrastructure of a somatic spine mat for nicotinic signaling in neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:748–756. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-00748.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosinsky GE, Giepmans BN, Deerinck TJ, Gaietta GM, Ellisman MH. Markers for correlated light and electron microscopy. Methods Cell Biol. 2007;79:575–591. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(06)79023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosinsky GE, Deerinck TJ, Greco R, Buitenhuys CH, Bartol TM, Ellisman MH. Development of a model for microphysiological simulations: small nodes of ranvier from peripheral nerves of mice reconstructed by electron tomography. Neuroinformatics. 2005;3:133–162. doi: 10.1385/NI:3:2:133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]