Abstract

The angiogenic, neovascular proliferative retinopathies, proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR), and age-dependent macular degeneration (AMD) complicated by choroidal neovascularization (CNV), also termed exudative or “wet” AMD, are common causes of blindness. The antidiabetic thiazolidinediones (TZDs), rosiglitazone, and troglitazone are PPARγ agonists with demonstrable antiproliferative, and anti-inflammatory effects, in vivo, were shown to ameliorate PDR and CNV in rodent models, implying the potential efficacy of TZDs for treating proliferative retinopathies in humans. Activation of the angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1-R) propagates proinflammatory and proliferative pathogenic determinants underlying PDR and CNV. The antihypertensive dual AT1-R blocker (ARB), telmisartan, recently was shown to activate PPARγ and improve glucose and lipid metabolism and to clinically improve PDR and CNV in rodent models. Therefore, the TZDs and telmisartan, clinically approved antidiabetic and antihypertensive drugs, respectively, may be efficacious for treating and attenuating PDR and CNV humans. Clinical trials are needed to test these possibilities.

1. INTRODUCTION

Angiogenesis and neovascularization involve formation and proliferation of new blood vessels and have a vital role normal growth and development, such as embryogenesis, wound healing, tissue repair [1, 2]. However, in pathological neovascularization, angiogenesis is aberrant and unregulated resulting in the formation of dysfunctional blood vessels [3]. The latter occurs in proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) and choroidal neovascularization (CNV), “wet” or exudative age-dependent macular degeneration (AMD), wherein pathological neovascular vessels proliferate and leak fluid leading to retinal edema, subretinal and retinal/vitreous hemorrhage, retinal detachment, and blindness. In the United States, PDR is the most common preventable cause of blindness in adults <50 years [4], whereas CNV/AMD is the leading cause of blindness among people of European origin >65 years [5]. Both retinopathies are progressively destructive, leading to eventual and irreversible blindness. PDR is a serious microvascular complication of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes [6]. Type 2 diabetes is rapidly expanding worldwide and is estimated to reach 380 million by 2025 [7, 8]. PDR is progressive and compounded by persistent and substandard control of hyperglycemia, and concomitant cardiovascular risk factors, especially hypertension [9–11]. Nearly, all type 1 diabetics and >60% of type 2 diabetics have significant retinopathy after 20 years, emphasizing the need for more cost-effective therapy [6, 10, 11]. Hyperglycemia, advanced glycation end-products (AGEs), and hypoxia are believed to induce pathological angiogenesis and neovascularization within the retina [12]. Prevention of end-organ damage by early and aggressive diabetes management is the best approach to treating diabetic retinopathy (DR) [6, 12].

Visual acuity depends on a functional macula, located at the center of the retina where cone photoreceptors are most abundant. Exudative (wet) AMD is complicated by CNV, involving activation and migration of macrophages, and normally quiescent retinal pigment epithelial cells from the choroid and invasion of defective neovascular blood vessels into the subretinal space [13, 14]. Bleeding and lipid leakage from these immature vessels damage the retina and lead to severe vision loss and blindness [14, 15]. Current therapies of AMD are limited to treating the early stages of the disease, and include laser photocoagulation, photodynamic therapy, surgical macular translocation, and antiangiogenesis agents [13–16]. These invasive procedures are expensive, require repetition, whereas pharmacologic approaches could simplify therapy and reduce cost.

The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) class of nuclear receptors (PPARα, PPARβ/δ, and PPARγ) belongs to the nuclear receptor superfamily that include the steroid, thyroid hormone, vitamin D, and retinoid receptors [17, 18]. In 1995, Lehmann et al. [19] discovered that PPARγ was the intracellular high affinity receptor for the insulin-sensitizing, antidiabetic thiazolidinediones (TZDs), the activation of which also promotes growth arrest of preadipocytes, differentiation, adipogenesis, and differentiation into mature adipocytes [20]. Ligand activation of PPARγ also downregulates the transcription of genes encoding inflammatory molecules, inflammatory cytokines, growth factors, proteolytic enzymes, adhesion molecules, chemotactic, and atherogenic factors [21–25] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, and other proinflammatory mediators downregulated by PPARγ activation. PDGF-BB, platelet-derived growth factor-BB homodimer; AP-1, activated protein-1; NF-κB = nuclear factor-κB; NFAT = nuclear factor of activated T lymphocytes; STAT = signal transducer and activator of transcription; ICAM, intracellular adhesion molecule; VCAM, vascular cell adhesion molecule; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase. (Adapted with permission from: B. Staels, “PPARγ and atherosclerosis.” Current Medical Research and Opinion, vol. 21, Suppl. 1, pp. S13-S20, 2005; H. A. Pershadsingh, “Dual peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha/gamma agonists : in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus and the metabolic syndrome.” Treatments in Endocrinology, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 89-99, 2006.)

| Growth factors | Cytokines | Chemokines | Nuclear transcription factors | Other molecules |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATII | IL-1β | IL-8 | AP-1 | IFN-γ |

| TGF-β | IL-2 | MCP-1 | NF-κB | iNOS |

| ET-1 | IL-6 | RANTES | STAT | PAI-1 |

| bFGF | TNF-α | NFAT | MMP-2 | |

| PDGF-BB | MMP-9 | |||

| EGF | VCAM-1 | |||

| VEGF | ICAM-1 | |||

| E-selectin |

Angiotensin II (AII) and components of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) are expressed in the retina [26, 27]. AII promotes retinal leukostasis by activating the angiotensin type 1 receptor (AT1-R) pathway that propagates proinflammatory, proliferative mediators (Table 2) leading to the development and progression of PDR [28–30] and CNV [31]. By selectively blocking the AT1-R, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) or “sartans,” for example, valsartan and telmisartan have been shown to confer neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects in animal models of retinal angiogenesis and neovascularization [32–36]. Among the seven approved ARBs, telmisartan and irbesartan were recently shown to constitute a unique subset of ARBs also capable of activating PPARγ [37–39]. Valsartan and the remaining ARBs were inactive in the PPARγ transactivation assay. In fact, telmisartan was shown to downregulate AT1 receptors through activation of PPARγ [40]. Telmisartan was shown to provide therapeutic benefits in rodent models of PDR [33, 41–44] and CNV [45] but data with irbesartan is unavailable. Therefore, telmisartan and possibly irbesartan (data unavailable) may have enhanced efficacy in treating proliferative retinopathies. ARBs are safe and have beneficial cardiometabolic, anti-inflammatory, and antiproliferative effects. Among these telmisartan and irbesartan may have improved efficacy for targeting proliferative retinopathies. Table 3 provides relevant information on the various drugs described herein.

Table 2.

Growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, and other proinflammatory mediators upregulated by angiotensin II stimulation. ET-1, endothelin-1; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; CTGF, connective tissue growth factor; bFGF, basic fibroblast growth factor; PDGF-AA, platelet-derived growth factor-AA homodimer; EGF, epidermal growth factor; VEGF, vascular endothelial cell growth factor; IL, interleukin; GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; MIP, macrophage inflammatory protein; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; NFAT, nuclear factor of activated T lymphocytes; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription; RANTES, regulated on activation, normal T-cell expressed and secreted; IFN-γ, interferon-γ; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1; AP-1, activated protein-1. (Adapted with permission from: R. E. Schmieder, K. F. Hilgers, M. P. Schlaich, B. M. Schmidt, “Renin-angiotensin system and cardiovascular risk.” Lancet, vol. 369, no. 9568, pp. 1208-1219, 2007.)

| Growth factors | Cytokines | Chemokines | Other proinflammatory molecules |

|---|---|---|---|

| ET-1 | IL-1β | IL-8 | IFN-γ |

| TGF-β | IL-6 | MCP-1 | Tissue factor |

| CTGF | IL-18 | MIP-1 | PAI-1 |

| bFGF | GM-CSF | RANTES | |

| PDGF-AA | TNF-α | ||

| EGF | |||

| VEGF |

Table 3.

Comparison of pharmacological and other relevant properties of thiazolidinedione (TZD) full PPARγ agonists and dual angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker/selective PPARγ modulator (ARB/SPPARγM).

| Parameter | TZDs† | ARBs* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Troglitazone | Pioglitazone | Rosiglitazone | Telmisartan | Irbesartan | |

| Primary pharmacological target | PPARγ | PPARγ | PPARγ | AT1-R | AT1-R |

| Type of PPARγ agonists | Full PPARγ agonists | Selective PPARγ modulator (SPPARγM) | |||

| Drug class (common names) | Thiazolidinedione (TZDs) | Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) | |||

| PPARγ activation (EC50 in μM) | 0.55 | 0.58 | 0.043 | 4.5 | 27 |

| Therapeutic indication | Treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus | Treatment of hypertension | |||

| Primary therapeutic mechanism | Increase insulin sensitivity | Lower blood pressure | |||

| Serious adverse effect (Black box warning) | Fluid retention/weight gain/heart failure | None | None | ||

| Supplier/Pharmaceutical Co. | Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo, USA | Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America, Deerfield, Ill, USA | GlaxoSmithKline, NC, USA | Boehringer- Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Ridgefield, Conn, USA | Sanofi-Aventis, Bridgewater, NJ, USA |

†Thiazolidinedione full PPARγ agonists; troglitazone was withdrawn from the market (1998) because of association with rare cases of fatal hepatic failure. Rosiglitazone and pioglitazone have no such known association.

*Other FDA-approved ARBs had EC50 values > 100μM (see [37, 38]). EC50 values shown were determined using the standard PPARγ-GAL4 transactivation assays.

2. TISSUE DISTRIBUTION PPARγ

Four PPARγ mRNA isoforms have been identified [46] that encode two proteins, PPARγ1 and PPARγ2 [47, 48]. PPARγ1 is the principal subtype expressed in diverse tissues, whereas PPARγ2 predominates in adipose tissue [49, 50]. The PPARγ2 protein differs from PPARγ1 by the presence of 30 additional amino acids [49]. Tissue-specific distribution of isoforms and the variability of isoform ratios raise the possibility that isoform expression might be modulated by or reflect disease states in which PPARγ activation or inactivation has a role. In humans, PPARγ is most abundantly expressed mainly in white adipose tissue and large intestine, and to a significant degree in kidney, heart, small intestine, spleen, ovary, testis, liver, bone marrow, bladder, epithelial keratinocytes, and to a lesser extent in skeletal muscle, pancreas, and brain [51].

2.1. PPARγ expression in the eye

PPARγ is heterogeneously expressed in the mammalian eye [51–53]. PPARγ was found to be most prominent in the retinal pigmented epithelium, photoreceptor outer segments, choriocapillaris, choroidal endothelial cells, corneal epithelium, and endothelium, and to a lesser extent, in the intraocular muscles, retinal photoreceptor inner segments and outer plexiform layer, and the iris [52]. Ligand-dependent activation of PPARγ evokes potent inhibition of corneal angiogenesis and neovascularization [53–55]. The prominent expression of PPARγ in selected tissues of the retina [52–54] provides the rationale for pharmacotherapeutic targeting of PPARγ for treating ocular inflammation and proliferative retinopathies [53–56].

2.2. Importance of PPARγ in proliferative retinopathy

To determine whether endogenous PPARγ played a role in experimental DR, Muranaka et al. [54] evaluated retinal leukostasis and retinal (vascular) leakage in streptozotocin-induced diabetic C57BL/6 mice deficient in PPARγ expression (heterozygous genotype, PPARγ+/−) after 120 days. Retinal leukostasis and leakage were greater (205% and 191%, resp.) in the diabetic PPARγ+/− mice, compared to diabetic wild-type (PPARγ+/+) mice. In streptozotocin-induced diabetic Brown Norway rats, oral administration of the TZD PPARγ ligand, rosiglitazone for 21 days (3 mg/kg body weight/day, initiated post-streptozotocin injection) resulted in suppression of retinal leukostasis by 60.9% (P < .05), and retinal leakage by 60.8% (P < .05) [54]. Expression of the inflammatory molecule. ICAM-1 protein was upregulated in the retina of the rosiglitazone-treated group, though the levels of VEGF and TNF-α were unaffected [54]. These findings provide strong evidence for a role of PPARγ activity in the pathogenesis of DR and provide novel genomic information that therapeutic targeting of PPARγ with a known PPARγ ligand, the TZD rosiglitazone, can attenuate the progression of PDR. Whether a similar effect may apply to the prevention or attenuation of CNV is currently unknown and should be explored.

3. ANTIDIABETIC THIAZOLIDINEDIONES (TZDs) AND PROLIFERATIVE RETINOPATHIES

The insulin-sensitizing TZDs, rosiglitazone, and pioglitazone are approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Because they increase target tissue sensitivity to insulin without increasing insulin secretion [57], there is no risk of hypoglycemia, though there is a risk fluid retention in diabetic patients, especially those with coexisting heart failure, or at risk for developing CHF [58].

By activating PPARγ, TZDs modulate groups of genes involved in energy metabolism [59], inflammation, and cellular differentiation [60–64] by down-regulating the activity of the proinflammatory nuclear receptors (NF-κB, AP-1, STAT, NFAT), and inhibiting the activity and expression of inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6), iNOS, proteolytic enzymes (MMP-3 and MMP-9), and growth factors (VEGF, PDGF-BB, bFGF, EGF, TGF-β) (Table 1). Because of these broadly beneficial and protective actions of PPARγ agonists, TZDs have been under development for the treatment of conditions beyond type 2 diabetes, including atherosclerosis [64, 65], psoriasis [66], inflammatory colitis [67], nonalcoholic steatohepatitis [68], and Alzheimer’s disease [69]. More recently, TZDs have been found to protect against glutamate cytotoxicity in retinal ganglia and have antioxidant properties [70] suggesting that PPARγ agonists could prove valuable in targeting retinal complications [71].

3.1. Therapeutic effects on proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR)

Retinal capillaries consist of endothelial cells, basement membrane neovascularization, and intramural pericytes within the basement membrane which are important in vascular development and maturation [44]. Selective loss of pericytes from the retinal capillaries characteristically occurs early in diabetic retinopathy (DR) [72]. Diabetic macular edema (DME), often associated with PDR, involves breakdown of the blood-retinal barrier and leakage of plasma from blood vessels in the macula causing macular edema and impaired vision [73, 74]. Resorption of the fluid from plasma leads to lipid and lipoprotein deposition forming hard exudates [75]. In PDR, inflammation leads to endothelial dysfunction, retinal vascular permeability, vascular leakage, and adhesion of leukocytes to the retinal vasculature (leukostasis), progressive capillary nonperfusion, and DME [12]. Intraretinal microvascular abnormalities and progressive retinal ischemia lead to neovascular proliferation within the retina, bleeding, vitreous hemorrhage, fibrosis, and retinal detachment [74–76]. Despite advancements in ophthalmologic care and the management of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes, PDR remains a leading cause of preventable blindness [5–7]. Primary interventions, especially intensive glycemic and blood pressure control, and management of other cardiovascular risk factors are essential [6, 73–75]. Focal laser photocoagulation remains the only surgical option for reducing significant visual loss in eyes with macular edema [6, 9–12]. The risk of blindness with untreated PDR is currently greater than 50% at 5 years, but can be reduced to less than 5% with appropriate therapy [5–7]. At present, there is insufficient evidence for the efficacy or safety of pharmacological interventions, including therapy targeting vascular endothelial growth factor (i.e., anti-VEGF antibody therapy), though intravitreal glucocorticoids may be considered when conventional treatments have failed [6, 12].

Troglitazone and rosiglitazone were shown to attenuate VEGF-induced retinal endothelial cell proliferation, migration, tube formation, and signaling, in vitro [55] by arresting the growth cycle of endothelial cells [62]. Local intrastromal implantation of micropellets containing pioglitazone into rat corneas significantly decreased the density of VEGF-induced angiogenesis, an accepted animal model of retinal neovascularization [53].

Adverse conditions that contribute to macular edema and retinal degeneration in PDR include generation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs), local ischemia, oxidative reactions, and hyperglycemia-induced toxicity [72, 75, 76]. In PPARγ-expressing retinal endothelial cells, troglitazone, and rosiglitazone inhibited VEGF-stimulated proliferation, migration, and tube formation [55, 77]. The effects of troglitazone and rosiglitazone were also evaluated in the oxygen-induced ischemia murine model of retinal neovascularization, an experimental model of PDR [77]. Although the model lacks specific metabolic abnormalities found in diabetes, it isolates the VEGF-driven process in which neovascularization is stimulated by increased VEGF expression in the inner retina [77]. Both troglitazone and rosiglitazone decreased the number of microvascular tufts induced on the retinal surface, suggesting inhibition of an early aspect of neovascularization. The inhibitory effects were dose-dependent (IC50 ≃ 5 μmo1/L) [77]. These findings support the proposal that TZDs may have beneficial effects by reducing or delaying the onset of PDR in diabetic patients. Prospective clinical trials are required to demonstrate clinical efficacy.

3.2. Therapeutic effects on choroidal neovascularization (CNV)

AMD complicated with CNV involves angiogenesis and neovascularization in the choroid with hemorrhage in the subretinal space, fluid accumulation beneath the photoreceptors within the fovea, and neural cell death in the outer retina [13–16]. CNV is present with vascular inflammation, unbridled vascular proliferation, aberrant epithelial and endothelial cell migration, and inappropriate production of proinflammatory cytokines, inducible nitric oxide synthase, growth factors, proteolytic enzymes, adhesion molecules, chemotactic factors, atherogenic, and other mediators that propagate defective blood vessel proliferation [5, 13–16, 78]. Elevated blood pressure, serum lipids, smoking, and insulin resistance also have an etiological role in CNV development [78]. Therefore, control of cardiometabolic risk factors is important in palliative management of CNV [79, 80]. Recently, therapy for early exudative AMD has been directed toward intravitreal injection of VEGF-directed antibodies or fragments thereof [14–16]. However, excessive cost ($1,950/dose) is a major issue [http://www.globalinsight.com/SDA/SDADetail6273.htm]. Monthly treatments are difficult for patients to tolerate, and the risk of serious adverse effects increases over time [16]. On the other hand, synthetic, nonpeptide PPARγ agonists [81, 82] are straightforward to synthesize, inexpensive to formulate.

CNV comprises the underlying pathology of exudative AMD, principally involving the subretinal vasculature and choriocapillaris, leading to capillary closure and retinal ischemia, angiogenesis, retinal neovascularization, bleeding into the vitreous, retinal detachment and degeneration, and eventually vision loss [13–16]. PPARγ is expressed in the choriocapillaris, choroidal endothelial cells, retinal endothelial cells, and retinal pigmented epithelium [52, 83]. VEGF is a potent inducer of retinal [13–16] angiogenesis and neovascularization. In their landmark study, Murata et al. [83] demonstrated the expression of PPARγ1 in human retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells and bovine choroidal endothelial cells (CECs), and that application of the TZDs troglitazone or rosiglitazone (0.1–20 μmol/L) inhibited VEGF-induced proliferation and migration of RPE and CEC cells, and neovascularization [83]. Moreover, in the eyes of rat and cynomolgus monkeys in which CNV was induced by laser photocoagulation, intravitreal injection of troglitazone markedly inhibited CNV compared to control eyes (P < .001). The treated lesions showed significantly less fluorescein leakage and were histologically thinner in troglitazone-treated animals, without adverse effects in the adjacent retina or in control eyes [83]. These findings suggest that pharmacological activation of PPARγ by TZDs appear to have a palliative or therapeutic effect on experimental CNV. Again, clinical trials are required to demonstrate efficacy in the clinical setting.

3.3. Adverse effects of TZDs: fluid retention and macular edema

Pioglitazone and rosiglitazone are generally safe though, in type 2 diabetic patients, there is a risk of weight gain (1–3 kg) and fluid retention [58]. The incidence of peripheral edema is greater in those concurrently taking exogenous insulin, increasing from 3.0–7.5% to 14.7–15.3% [58]. The edema may be related to TZD-induced vasodilation, increased plasma volume secondary to renal sodium reabsorption, and reflex sympathetic activation [58]. The association of rosiglitazone treatment with development of macular edema has been reported [84]. In a case review of 11 patients who developed peripheral and macular edema, while on the TZD therapy [85] 8 patients experienced resolution of macular edema with improved vision, without laser treatment, 3 months to 2 years after TZD cessation. Therefore, DME should be considered in type 2 diabetic patients treated with a TZD, especially those with peripheral edema, or other symptoms or risk factors of CHF, or concurrently taking exogenous insulin or nitrates. Drug cessation usually results in rapid resolution of both peripheral and macular edema [85].

4. ANTIHYPERTENSIVE ANGIOTENSIN RECEPTOR BLOCKERS (ARBs) THAT ACTIVATE PPARγ

In their search for PPARγ agonists that lack the adverse effects of TZDs, Benson et al. [37] screened the active forms of all currently available antihypertensive “sartans” (ARBs): losartan, valsartan eprosartan, irbesartan, candesartan, telmisartan, and olmesartan, using the standard GAL-4 cell-based PPARγ transactivation assay. Only telmisartan and irbesartan [37, 38] activated PPARγ and promoted adipogenesis, intracellular lipid accumulation and differentiation of preadipocyte fibroblasts into mature adipocytes, in vitro, hallmark properties of PPARγ agonists [19]. The EC50 values for transactivation of PPARγ by telmisartan and irbesartan were 4.5 μmol/L and 27 μmol/L, respectively [37–39] (Table 3). Although the PPARγ transactivation assay may not recapitulate conditions in vivo, based on pharmacokinetic considerations, concentrations of these ARBs required to activate PPARγ in vivo are achievable by standard dosing [86, 87]. By functioning as partial PPARγ agonists this unique subset of ARBs may provide added end-organ benefits in certain patient populations such patients with the metabolic syndrome [87] and other cardiometabolic risk factors, including atherosclerosis, atherogenesis, and may have palliative effects on proliferative retinopathies.

ARBs bear an acidic group (tetrazole or carboxyl group) at the ortho position on the terminal benzene ring of the biphenyl moiety, which is essential for AT1 receptor binding. Telmisartan bears a carboxyl and irbesartan, a tetrazole [87, 88]. The active forms of all other ARBs have two acidic groups at opposite molecular poles. This second acidic group limits accessibility, and hinders binding to the hydrophobic region of the PPARγ receptor [87, 88]. Therefore, among currently available ARBs, the molecular dipole appears to be an important structure-functional determinant of ligand binding to the PPARγ receptor [87]. Compared to all other ARBs, telmisartan has a uniquely long elimination half-life (24 hours), and the largest volume of distribution (500 L, and >10-fold in excess of other ARBs) which greatly increases central bioavailability upon oral dosing [86]. Furthermore, telmisartan has been shown to have significant anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity, which may enhance its effectiveness in attenuating the progression of proliferative retinopathies [89–91].

4.1. Full versus partial PPARγ agonists

The PPARγ receptor is composed of five different domains, an N-terminal region or domain A/B, a DNA binding domain C (DBD), a hinge region (domain D), a ligand binding domain E (LBD), and a domain F [81, 92, 93]. The A/B domain contains an activation function-1 (AF-1) that operates in absence of ligand. The DBD confers DNA binding specificity. PPARγ controls gene expression by binding to specific DNA sequences or peroxisome proliferation-responsive elements (PPREs) in the regulatory region of PPAR-responsive genes. The large LBD (∼1300 Å3) allows the receptor to interact with a broad range of structurally distinct natural and synthetic ligands [81, 92, 93]. The receptor protein contains 13 helices, and the activation function, AF-2 helix located in the C terminus of the LBD is intimately integrated with the receptor's coactivator binding domain [81]. Ligand-dependent stabilization is required for activation of the downstream transcriptional machinery [81, 92, 93].

Thiazolidinedione full agonists (TZDfa), for example, rosiglitazone and pioglitazone permit certain coactivators to interact with the PPAR-LBD in an agonist-dependent manner and are oriented by a “charge clamp” formed by residues within helix 3 and the AF-2 arm of helix 12 in the LBD [45, 93]. Based on protease digest patterns and crystallographic findings, the PPARγ non-TZD partial agonist (nTZDpa) [94] and PPARγ partial agonist/antagonist, GW0072 [95] are mainly stabilized by hydrophobic interactions with helixes H3 and H7.

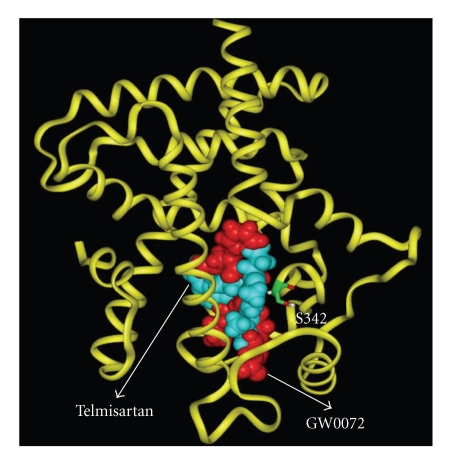

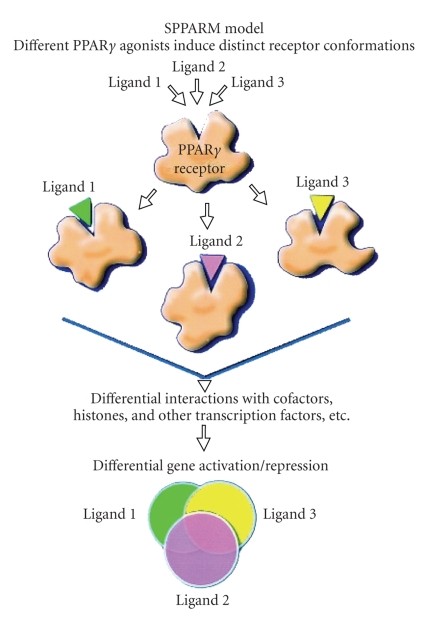

The antihypertensive ARBs telmisartan and irbesartan have been shown to function as partial PPARγ agonists, similar to the previously identified nTZDpa [94]. Based on molecular motifs, telmisartan appears to occupy a region in proximity with helix 3, with key interactions between the carboxylic acid group of the ligand and Ser342 near the entrance of the PPARγ pocket [37] (Figure 1). Telmisartan and irbesartan appear to cause an alteration in the conformation of these helixes similar to that induced by nTZDpa [37, 39], promoting differences in receptor activation and target gene expression that confer a low adipogenic potential compared with full agonists (TZDfa) like rosiglitazone and pioglitazone, which are known to have a high adipogenic potential and promote weight gain [58, 81, 94]. Differential binding motifs reflecting full versus partial PPARγ agonism are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Telmisartan (blue) superimposed on the co-crystal structure of GW0072 (red) bound within the PPARγ-LBD. Telmisartan and GW0072 are Van der Waals space-filling representations, and the protein backbone by the yellow ribbon. Formation of hydrogen bonds and interactions between both ligands and the amide proton of Ser342 contribute toward stabilization of the partial agonists within the PPARγ-LBD. (Kindly provided by Dr. P.V. Desai & Professor M.A. Avery, Department of Medicinal Chemistry, University of Mississippi, USA.)

Figure 2.

Selective PPARγ modulator (SPPARγM) model of PPARγ ligand action. PPARγ is a multivalent receptor whose ligand binding domain can accommodate different PPARγ ligands. Ligands 1, 2, or 3 (e.g., full agonist, partial agonist, or SPPARγM) are capable of inducing distinct receptor combinations leading to selective gene expression. Each ligand-receptor complex assumes a somewhat different three-dimensional conformation, leading to unique and differential interactions with cofactors, histones (acetylases/deacetylases), and other transcription factors. Consequently, each PPARγ ligand-receptor complex leads to a differential, but overlapping, pattern of gene expression. Thus, each ligand will activate, or repress multiple genes leading to differential overlapping expression of different sets of genes. (Adapted with permission from: J. M. Olefsky, “Treatment of insulin resistance with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonists.” Journal of Clinical Investigation, vol. 106, no. 4, pp. 467-472, 2000); H. A. Pershadsingh, “Treating the metabolic syndrome using angiotensin receptor antagonists that selectively modulate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma.” International Journal of Biochemistry and Cellular Biology, vol. 38, nos 5-6, pp. 766-781, 2006.)

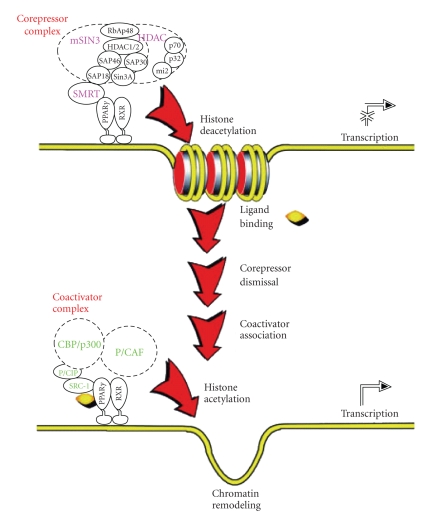

Several coactivators, including CREB-binding protein complex, CBP/p300, steroid receptor coactivator (SRC)-1, nuclear receptor corepressor (NcoR), DRIP204, PPAR binding protein (PBP)/TRAP220, and PPARγ coactivator-1 (PGC-1), among others, interface functionally between the nuclear receptor and the transcription initiation machinery in ways not well understood [94]. Differential ligand-induced initiation of transcription is the consequence of differential recruitment and release of selective coactivators and corepressors [96] (Figure 3). For example, NcoR a silencing mediator when bound to PPARγ suppresses adipogenesis in the absence of ligand. Activation by TZDfa ligands causes release of NcoR and recruitment of the nuclear receptor coactivator complex, NcoA/SRC-1 which promotes adipogenesis and lipid storage [94].

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of the mechanisms of PPARγ action. In the unliganded state (top), the PPARγ receptor exists as a heterodimer with the RXR nuclear receptor and the heterodimer is located on a PPAR response element (PPRE) of a target gene. The unliganded receptor heterodimer complex is associated with a multicomponent corepressor complex, which physically interacts with the PPARγ receptor through silencing mediator for retinoid and thyroid hormone receptors (SMRT). The corepressor complex contains histone deacetylase (HDAC) activity, and the deacetylated state of histone inhibits transcription. After PPARγ ligand binding, the corepressor complex is dismissed, and a coactivator complex is recruited to the heterodimer PPARγ receptor (bottom). The coactivator complex contains histone acetylase activity, leading to chromatin remodeling, facilitating active transcription. (Adapted with permission from: J. M. Olefsky, “Treatment of insulin resistance with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonists.” Journal of Clinical Investigation, vol. 106, no. 4, pp. 467-472, 2000); C. K. Glass, M. G. Rosenfeld, “The coregulator exchange in transcriptional functions of nuclear receptors”. Genes & Development,vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 121-141, 2000.)

Demonstration of direct interaction between telmisartan or irbesartan with PPARγ protein, by analyzing migration patterns of ligand-PPARγ protein fragments in trypsin digestion experiments, indicated that both ARBs downregulated PPARγ mRNA and protein expression in 3T3-L1 human adipocytes, a known property of PPARγ ligands in adipocytes [39]. In fact, both telmisartan and irbesartan caused release of NCoR and recruitment of NCoA/DRIP205 to PPARγ in a concentration-dependent manner [39]. The transcription intermediary factor 2 (TIF-2), an adipogenic coactivator implicated in PPARγ-mediated lipid uptake and storage, which increased the transcriptional activity of PPARγ, was potentiated by pioglitazone but not by the ARBs [39]. Moreover, irbesartan and telmisartan also induced PPARγ activity in an AT1R-deficient cell model (PC12W), demonstrating that their effects on PPARγ activity were independent of their AT1-R blocking actions [38]. These data demonstrate the functional relevance of selective cofactor docking by the ARBs, and compared to pioglitazone, identify telmisartan and irbesartan as unique selective PPARγ modulators (SPPARγMs) that can retain the metabolic efficacy of PPARγ activation, while reducing adverse effects, in parallel AT1-R blockade [37–39, 88]. Therefore, as dual ARB/SPPARγM ligands, telmisartan and irbesartan have important differential effects on PPARγ-dependent regulation of gene transcription, without the limitations of fluid retention and weight gain, providing improved therapeutic efficacy by combining potent antihypertensive, antidysmetabolic, anti-inflammatory, and antiproliferative actions in the treatment of the proliferative retinopathies.

4.2. Expression of the renin-angiotensin system in the eye

The RAS evolved to maintain volume homeostasis and blood pressure through vasoconstriction, sympathetic activation, and salt and water retention [97]. AII binds and activates two primary receptors, AT1-R, and AT2-R. In adult humans, activation of the AT1-R dominates in pathological states, leading to hypertension, atherosclerosis, cardiac failure, end-organ demise (e.g., nephropathy), and proliferative retinopathies. AT2-R activation generally has beneficial effects, counterbalancing the actions propagated through AT1-R. ARBs selectively block AT1-R, leaving AII to interact with the relatively beneficial AT2-R. AII is generated in cardiovascular, adipose, kidney, adrenal tissue, and the retina; and through AT1-R activation promotes cell proliferation, migration, inflammation, atherogenesis, and extracellular matrix formation [97].

AII and genes enconding angiotensinogen, renin, and angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) have been identified in the human neural retina [98]. Prorenin and renin have been identified in diabetic and nondiabetic vitreous, and intravitreal prorenin is increased in PDR [99]. Angiotensin I and AII were found to be present in ocular fluids of diabetic and nondiabetic patients [100]. AII and VEGF have been identified in the vitreous fluid of patients with PDR [101], and AT1 and AT2 were identified in the neural retina [102]. Furthermore, AT1 and AT2, AII, and its bioactive metabolite Ang-(1–7) were identified in blood vessels, pericytes, and neural (Müller) cells suggesting that these glial cells are able to produce and process AII [102]. Thus, AII signaling via the AT1 pathway within the retina may mediate autoregulation of neurovascular activity, and the onset and severity of retino-vascular disease [103].

4.3. Pathophysiological role of AT1 activation in proliferative retinopathies

AT1 activation participates in the pathogenesis of PDR, involving inflammation, oxidative stress, cell hypertrophy and proliferation, angiogenesis, and fibrosis [101, 103]. The RAS is upregulated concomitant with hypoxia-induced retinal angiogenesis [102–104] and is linked to AII-mediated induction of inflammatory mediators and growth factors, including VEGF and PDGF [103–106]. AT1 blockade with candesartan inhibited pathological retinopathy in spontaneously diabetic Torii rats by reducing the accumulation of the advanced glycation end-product (AGE) pentosidine [34]. AGEs contribute to vascular dysfunction by increasing the activity of VEGF and reactive oxygen species [34]. Treatment with candesartan reduced the accumulation pentosidine and VEGF gene expression in the diabetic rat retina [34]. AT1-R, AT2-R, and AII were shown to be expressed in the vascular endothelium of surgical samples from human CNV tissues and chorioretinal tissues from mice in which CNV was laser-induced [40]. Therefore, the retinal RAS appears to have an important pathophysiological role in proliferative retinopathies.

4.4. Therapeutic effects of telmisartan on PDR and CNV

AII is among the most potent vasopressive hormones known and contributes to the development of leukostasis in early diabetes [29]. Hypertension increases retinal inflammation and exacerbates oxidative stress in experimental DR [34, 107], and in diabetic hypertensive rats, prevention of hypertension abrogaItes retinal inflammation and leukostasis in early DR [108]. Therefore, RAS blockade by the dual ARB/PPARγ agonists, telmisartan or irbesartan, may have enhanced effects for abrogating inflammatory and other pathological events that contribute to or exacerbate PDR and CNV/AMD. In clinical studies, reduction of hypertension by any means reduces the risk of development and the progression of DR [109]. ARBs are widely used antihypertensive agents clinically.

Induction of diabetes by streptozotocin injection in C57BL/6 mice caused significant leukostasis and increased retinal expression and production of AII, AT1-R, and AT2-R [30]. Intraperitoneal administration of telmisartan inhibited diabetes and glucose-induced retinal expression of ICAM-1 and VEGF, and upregulation of ICAM-1 and MCP-1, via inhibition of nuclear translocation of NF-κB [33]. There have been no reports on the effects of irbesartan on PDR or CNV/AMD.

In the laser-induced mouse model of CNV, new vessels from the choroid invade the subretinal space after photocoagulation, reflecting the choroidal inflammation and neovascularization seen in human exudative AMD. Based a recent suggestion [110], Nagai et al. [45] evaluated and compared the effects of telmisartan with valsartan, an ARB lacking significant PPARγ activity [38, 39], and suitable control to evaluate the role of telmisartan PPARγ activity. Both ARBs have identical affinities for the AT1-R (∼10 nmo1/L) [97]. Telmisartan (5 mg/kg, i.p.) or valsartan (10 mg/kg, i.p.) significantly suppressed CNV in mice [45]. Simultaneous administration of the selective PPARγ antagonist GW9662, partially (22%) but significantly reversed the suppression of CNV in the group receiving telmisartan but not the group receiving valsartan [45], indicating separate beneficial contributions via AT1 blockade and PPARγ activation, respectively [45]. Using GW9662, similar findings were obtained identifying participation of PPARγ in the suppressive effect of telmisartan on the inflammatory mediators, ICAM-1, MCP-1, VEGFR-1 in b-End3 vascular endothelial cells, and VEGF and in RAW264.7 macrophages, unrelated to AT1 blockade [45]. These findings confirm that the beneficial effects of telmisartan are derived from a combination of AT1 blockade and PPARγ activation. The inhibitory effects of valsartan were insensitive to the presence of GW9662. This is the first known demonstration of PPARγ-dependent inhibitory actions of a non-TZD PPARγ agonist on CNV. There have been no reports on the effects of irbesartan on PDR or CNV.

4.5. Therapeutic potential of dual ARB/SPPARγMs

Reduction in the cardiometabolic risk profile by lowering high blood pressure, improving insulin sensitivity, normalizing the lipid profile, and inhibiting inflammatory pathways are known to impede the pathological evolution of proliferative retinopathies. The dual ARB/SPPARγM ligands, telmisartan has been shown to be effective in this regard in the rodent model, though irbesartan has yet to be tested experimentally. PPARγ activation has beneficial effects by lowering hyperglycemia and improving the metabolic profile in individuals with type 2 diabetes and the metabolic syndrome. The fact that both AT1-R blockade and PPARγ activation by telmisartan had independent synergistic effects in the murine model of laser-induced CNV is an important finding [40]. It would be useful to test whether irbesartan has effects similar to those of telmisartan in animal models of PDR and CNV/AMD [28, 31–34, 40], as both ARBs similarly attenuate inflammation, proliferation, and improve the metabolic syndrome [111, 112]. Also, unlike TZDs, telmisartan (but not valsartan) increases caloric expenditure and protects against weight gain and hepatic steatosis [113]. With its high lipid solubility, large volume of distribution, and other favorable pharmacokinetic properties [86–88], telmisartan may be effective when administered orally. If oral delivery proves therapeutically ineffective, the drug may be formulated for administration via implant or transscleral application for local delivery to the posterior segment [114–116].

5. CONCLUDING REMARKS

Hypertension, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and risk for atherosclerosis and atherogenesis, all components of the metabolic syndrome, comprise significant epidemiologic risk factors for neovascular, proliferative retinopathies [6, 9, 12, 117, 118]. Photodynamic and anti-VEGF therapy, current treatments for CNV/AMD are cost-intensive. Treatments for PDR are limited to surgical options in advanced disease when the visual function is irreversibly affected [3–6, 14–16]. Therefore, alternative, low cost, prophylactic and/or palliative pharmacotherapeutic approaches are attractive and desirable. The currently approved antidiabetic TZD, rosiglitazone (a full PPARγ agonist), and the antihypertensive ARB, telmisartan (a partial PPARγ agonist) have both shown promise in animal models of proliferative retinopathies. The potential efficacies of irbesartan in proliferative retinopathies remain to be determined. Administration of TZDs may, in patients with AMD, slow the progression to CNV, and in patients with diabetic retinopathy attenuate the progress to PDR, provided that: (1) their risk of macular edema is low, (2) they lack symptoms of CHF or cardiomyopathy, and (3) are not taking insulin or nitrates. The efficacy and safety limitations of the TZDs are well understood [119–123] and their use would require careful benefit-to-risk analysis. Because these drugs have been in use clinically for a decade, well-designed retrospective analyses in carefully selected patient populations may reveal useful information regarding their clinical potential.

Several SPPARγMs currently which are under development for treating type 2 diabetes [124] could be screened in animal models of PDR and CNV to determine their potential efficacy for treating proliferative retinopathies. Long-term, prospective clinical trials are needed to demonstrate the efficacy of currently approved TZDs and ARBs (Table 3). Notably, three large prospective phase III trials are underway to evaluate the effect of the ARB, candesartan on retinopathy in normotensive type 1 and type 2 diabetes patients, the diabetic REtinopathy candesartan trials (DIRECTs) Programme [125]; estimated study completion date: June 2008. These studies will provide important insight into the potential efficacy of ARBs in general in the treatment of DR. With their capacity for activating PPARγ and improving the metabolic profile, the clinical efficacy of telmisartan and possibly irbesartan could be evaluated in patients at risk for developing PDR and CNV, especially those with deficiencies in carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. Moreover, with their unique structure/activity profile, these compounds may provide a drug discovery platform for designing therapeutic agents for treating proliferative retinopathies.

References

- 1.Eming SA, Brachvogel B, Odorisio T, Koch M. Regulation of angiogenesis: wound healing as a model. Progress in Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. 2007;42(3):115–170. doi: 10.1016/j.proghi.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta K, Zhang J. Angiogenesis: a curse or cure? Postgraduate Medical Journal. 2005;81(954):236–242. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.023309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dorrell M, Uusitalo-Jarvinen H, Aguilar E, Friedlander M. Ocular Neovascularization: basic mechanisms and therapeutic advances. Survey of Ophthalmology. 2007;52(1) supplement 1:S3–S19. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2006.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kempen JH, O'Colmain BJ, Leske MC, et al. The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy among adults in the United States. Archives of Ophthalmology. 2004;122(4):552–563. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedman DS, O'Colmain BJ, Muñoz B, et al. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the United States. Archives of Ophthalmology. 2004;122(4):564–572. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohammedamed Q, Gillies MC, Wong TY. Management of diabetic retinopathy: a systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;298(8):902–916. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.8.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National diabetes fact sheet: general information and national estimates on diabetes in the United States. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, Ga, USA 2005.

- 8.International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas. 2003, http://www.eatlas.idf.org/webdata/docs/atlas%202003-summary.pdf.

- 9.Klein BEK. Overview of epidemiologic studies of diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmic Epidemiology. 2007;14(4):179–183. doi: 10.1080/09286580701396720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matthews DR, Stratton IM, Aldington SJ, Holman RR, Kohner EM. Risks of progression of retinopathy and vision loss related to tight blood pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus: UKPDS 69. Archives of Ophthalmology. 2004;122(11):1631–1640. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.11.1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sjølie AK, Stephenson J, Aldington S, et al. Retinopathy and vision loss in insulin-dependent diabetes in Europe: the EURODIAB IDDM Complications Study. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(2):252–260. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30327-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ciulla TA, Amador AG, Zinman B. Diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema: pathophysiology, screening, and novel therapies. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(9):2653–2664. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.9.2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zarbin MA. Current concepts in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Archives of Ophthalmology. 2004;122(4):598–614. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donati G. Emerging therapies for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: state of the art. Ophthalmologica. 2007;221(6):366–377. doi: 10.1159/000107495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nowak JZ. Age-related macular degeneration (AMD): pathogenesis and therapy. Pharmacological Reports. 2006;58(3):353–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emerson MV, Lauer AK. Emerging therapies for the treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration and diabetic macular edema. BioDrugs. 2007;21(4):245–257. doi: 10.2165/00063030-200721040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mangelsdorf DJ, Thummel C, Beato M, et al. The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade. Cell. 1995;83(6):835–839. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kliewer SA, Forman BM, Blumberg B, et al. Differential expression and activation of a family of murine peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1994;91(15):7355–7359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lehmann JM, Moore LB, Smith-Oliver TA, Wilkison WO, Willson TM, Kliewer SA. An antidiabetic thiazolidinedione is a high affinity ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270(22):12953–12956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.12953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Altiok S, Xu M, Spiegelman BM. PPARγ induces cell cycle withdrawal: inhibition of E2F/DP DNA-binding activity via down-regulation of PP2A. Genes & Development. 1997;11(15):1987–1998. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.15.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pershadsingh HA. Pharmacological peroxisome proliferator-activated receptorγ ligands: emerging clinical indications beyond diabetes. Expert Opinion in Investigational Drugs. 1999;8(11):1859–1872. doi: 10.1517/13543784.8.11.1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gelman L, Fruchart J-C, Auwerx J. An update on the mechanisms of action of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) and their roles in inflammation and cancer. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 1999;55(6-7):932–943. doi: 10.1007/s000180050345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chinetti G, Fruchart J-C, Staels B. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and inflammation: from basic science to clinical applications. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders. 2003;27(supplement 3):S41–S45. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Michalik L, Wahli W. Involvement of PPAR nuclear receptors in tissue injury and wound repair. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2006;116(3):598–606. doi: 10.1172/JCI27958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kostadinova R, Wahli W, Michalik L. PPARs in diseases: control mechanisms of inflammation. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2005;12(25):2995–3009. doi: 10.2174/092986705774462905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarlos S, Wilkinson-Berka JL. The renin-angiotensin system and the developing retinal vasculature. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2005;46(3):1069–1077. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Senanayake P, Drazba J, Shadrach K, et al. Angiotensin II and its receptor subtypes in the human retina. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2007;48(7):3301–3311. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagai N, Noda K, Urano T, et al. Selective suppression of pathologic, but not physiologic, retinal neovascularization by blocking the angiotensin II type 1 receptor. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2005;46(3):1078–1084. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen P, Scicli GM, Guo M, et al. Role of angiotensin II in retinal leukostasis in the diabetic rat. Experimental Eye Research. 2006;83(5):1041–1051. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clermont A, Bursell S-E, Feener EP. Role of the angiotensin II type 1 receptor in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy: effects of blood pressure control and beyond. Journal of Hypertension. 2006;24(supplement 1):S73–S80. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000220410.69116.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagai N, Oike Y, Izumi-Nagai K, et al. Suppression of choroidal neovascularization hy inhibiting angiotensin-converting enzyme: minimal role of bradykinin. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2007;48(5):2321–2326. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kurihara T, Ozawa Y, Shinoda K, et al. Neuroprotective effects of angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R) blocker, telmisartan, via modulating AT1R and AT2R signaling in retinal inflammation. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2006;47(12):5545–5552. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagai N, Izumi-Nagai K, Oike Y, et al. Suppression of diabetes-induced retinal inflammation by blocking the angiotensin II type 1 receptor or its downstream nuclear factor-κB pathway. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2007;48(9):4342–4350. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sugiyama T, Okuno T, Fukuhara M, et al. Angiotensin II receptor blocker inhibits abnormal accumulation of advanced glycation end products and retinal damage in a rat model of type 2 diabetes. Experimental Eye Research. 2007;85(3):406–412. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilkinson-Berka JL, Tan G, Jaworski K, Ninkovic S. Valsartan but not atenolol improves vascular pathology in diabetic Ren-2 rat retina. American Journal of Hypertension. 2007;20(4):423–430. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Phipps JA, Wilkinson-Berka JL, Fletcher EL. Retinal dysfunction in diabetic Ren-2 rats is ameliorated by treatment with valsartan but not atenolol. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2007;48(2):927–934. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benson SC, Pershadsingh HA, Ho CI, et al. Identification of telmisartan as a unique angiotensin II receptor antagonist with selective PPARγ-modulating activity. Hypertension. 2004;43(5):993–1002. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000123072.34629.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schupp M, Janke J, Clasen R, Unger T, Kintscher U. Angiotensin type 1 receptor blockers induce peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ activity. Circulation. 2004;109(17):2054–2057. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000127955.36250.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schupp M, Clemenz M, Gineste R, et al. Molecular characterization of new selective peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ modulators with angiotensin receptor blocking activity. Diabetes. 2005;54(12):3442–3452. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.12.3442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Imayama I, Ichiki T, Inanaga K, et al. Telmisartan downregulates angiotensin II type 1 receptor through activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ . Cardiovascular Research. 2006;72(1):184–190. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamagishi S-I, Amano S, Inagaki Y, et al. Angiotensin II-type 1 receptor interaction upregulates vascular endothelial growth factor messenger RNA levels in retinal pericytes through intracellular reactive oxygen species generation. Drugs under Experimental and Clinical Research. 2003;29(2):75–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amano S, Yamagishi S-I, Inagaki Y, Okamoto T. Angiotensin II stimulates platelet-derived growth factor-B gene expression in cultured retinal pericytes through intracellular reactive oxygen species generation. International Journal of Tissue Reactions. 2003;25(2):51–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamagishi S-I, Takeuchi M, Matsui T, Nakamura K, Imaizumi T, Inoue H. Angiotensin II augments advanced glycation end product-induced pericyte apoptosis through RAGE overexpression. FEBS Letters. 2005;579(20):4265–4270. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamagishi S-I, Matsui T, Nakamura K, Inoue H. Pigment epithelium-derived factor is a pericyte mitogen secreted by microvascular endothelial cells: possible participation of angiotensin II-elicited PEDF downregulation in diabetic retinopathy. International Journal of Tissue Reactions. 2005;27(4):197–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nagai N, Oike Y, Izumi-Nagai K, et al. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor-mediated inflammation is required for choroidal neovascularization. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2006;26(10):2252–2259. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000240050.15321.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou J, Wilson KM, Medh JD. Genetic analysis of four novel peroxisome proliferator receptor-γ splice variants in monkey macrophages. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2002;293(1):274–283. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00138-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Elbrecht A, Chen Y, Cullinan CA, et al. Molecular cloning, expression and characterization of human peroxisome proliferator activated receptors γ1 and γ2. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1996;224(2):431–437. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vidal-Puig AJ, Considine RV, Jimenez-Liñan M, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gene expression in human tissues: effects of obesity, weight loss, and regulation by insulin and glucocorticoids. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1997;99(10):2416–2422. doi: 10.1172/JCI119424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fajas L, Auboeuf D, Raspé E, et al. The organization, promoter analysis, and expression of the human PPARγ gene. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(30):18779–18789. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.30.18779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Braissant O, Foufelle F, Scotto C, Dauca M, Wahli W. Differential expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs): tissue distribution of PPAR-α, -β, and -γ in the adult rat. Endocrinology. 1996;137(1):354–366. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.1.8536636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Michalik L, Desvergne B, Dreyer C, Gavillet M, Laurini RN, Wahli W. PPAR expression and function during vertebrate development. International Journal of Developmental Biology. 2002;46(1):105–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pershadsingh HA, Benson SC, Marshall B, et al. Ocular diseases and peroxisome proliferatoractivated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) in mammalian eye. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. 1999;25, part 2 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sarayba MA, Li L, Tungsiripat T, et al. Inhibition of corneal neovascularization by a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ ligand. Experimental Eye Research. 2005;80(3):435–442. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Muranaka K, Yanagi Y, Tamaki Y, et al. Effects of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ and its ligand on blood-retinal barrier in a streptozotocin-induced diabetic model. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2006;47(10):4547–4552. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xin X, Yang S, Kowalski J, Gerritsen ME. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ ligands are potent inhibitors of angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(13):9116–9121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.9116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Giaginis C, Margeli A, Theocharis S. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ ligands as investigational modulators of angiogenesis. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 2007;16(10):1561–1572. doi: 10.1517/13543784.16.10.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fujita T, Sugiyama Y, Taketomi S, et al. Reduction of insulin resistance in obese and/or diabetic animals by 5-[4-(1-methylcyclohexylmethoxy)benzyl]-thiazolidine-2,4-dione (ADD-3878, U-63,287, ciglitazone), a new antidiabetic agent. Diabetes. 1983;32(9):804–810. doi: 10.2337/diab.32.9.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nesto RW, Bell D, Bonow RO, et al. Thiazolidinedione use, fluid retention, and congestive heart failure: a consensus statement from the American Heart Association and American Diabetes Association. Circulation. 2003;108(23):2941–2948. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000103683.99399.7E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rocchi S, Auwerx J. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma: a versatile metabolic regulator. Annals of Medicine. 1999;31(5):342–351. doi: 10.3109/07853899908995901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Delerive JC, Fruchart JC, Staels B. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in inflammation control. Journal of Endocrinology. 2001;169(3):453–459. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1690453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gervois P, Fruchart J-C, Staels B. Drug insight: mechanisms of action and therapeutic applications for agonists of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Nature Clinical Practice Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2007;3(2):145–156. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Touyz RM, Schiffrin EL. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in vascular biology-molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Vascular Pharmacology. 2006;45(1):19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Debril M-B, Renaud J-P, Fajas L, Auwerx J. The pleiotropic functions of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ . Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2001;79(1):30–47. doi: 10.1007/s001090000145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Glass CK. Potential roles of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ in macrophage biology and atherosclerosis. Journal of Endocrinology. 2001;169(3):461–464. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1690461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pfützner A, Weber MM, Forst T. Pioglitazone: update on an oral antidiabetic drug with antiatherosclerotic effects. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 2007;8(12):1985–1998. doi: 10.1517/14656566.8.12.1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Varani J, Bhagavathula N, Ellis CN, Pershadsingh HA. Thiazolidinediones: potential as therapeutics for psoriasis and perhaps other hyperproliferative skin disease. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 2006;15(11):1453–1468. doi: 10.1517/13543784.15.11.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wada K, Nakajima A, Blumberg RS. PPARγ and inflammatory bowel disease: a new therapeutic target for ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2001;7(8):329–331. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(01)02076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Harrison SA. New treatments for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Current Gastroenterology Reports. 2006;8(1):21–29. doi: 10.1007/s11894-006-0060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Watson GS, Cholerton BA, Reger MA, et al. Preserved cognition in patients with early Alzheimer disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment during treatment with rosiglitazone: a preliminary study. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2005;13(11):950–958. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.11.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Giannini S, Serio M, Galli A. Pleiotropic effects of thiazolidinediones: taking a look beyond antidiabetic activity. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation. 2004;27(10):982–991. doi: 10.1007/BF03347546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Aoun P, Simpkins JW, Agarwal N. Role of PPAR-γ ligands in neuroprotection against glutamate-induced cytotoxicity in retinal ganglion cells. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2003;44(7):2999–3004. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hammes H-P. Pericytes and the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. Hormone and Metabolic Research. 2005;37(supplement 1):S39–S43. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-861361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Klein R, Klein BEK, Moss SE, Cruickshanks KJ. The Wisconsin epidemiologic study of diabetic retinopathy: XVII. The 14-year incidence and progression of diabetic retinopathy and associated risk factors in type 1 diabetes. Ophthalmology. 1998;105(10):1801–1815. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)91020-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Davidson JA, Ciulla TA, McGill JB, Kles KA, Anderson PW. How the diabetic eye loses vision. Endocrine. 2007;32(1):107–116. doi: 10.1007/s12020-007-0040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Aiello LM. Perspectives on diabetic retinopathy. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2003;136(1):122–135. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(03)00219-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Joussen AM, Smyth N, Niessen C. Pathophysiology of diabetic macular edema. Developments in Ophthalmology. 2007;39:1–12. doi: 10.1159/000098495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Murata T, Hata Y, Ishibashi T, et al. Response of experimental retinal neovascularization to thiazolidinediones. Archives of Ophthalmology. 2001;119(5):709–717. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.5.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schlingemann RO. Role of growth factors and the wound healing response in age-related macular degeneration. Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 2004;242(1):91–101. doi: 10.1007/s00417-003-0828-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bourla DH, Young TA. Age-related macular degeneration: a practical approach to a challenging disease. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2006;54(7):1130–1135. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hogg RE, Woodside JV, Gilchrist SE, et al. Cardiovascular disease and hypertension are strong risk factors for choroidal neovascularization. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.07.031. Ophthalmology. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Willson TM, Brown PJ, Sternbach DD, Henke BR. The PPARs: from orphan receptors to drug discovery. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2000;43(4):527–550. doi: 10.1021/jm990554g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wexler RR, Greenlee WJ, Irvin JD, et al. Nonpeptide angiotensin II receptor antagonists: the next generation in antihypertensive therapy. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 1996;39(3):625–656. doi: 10.1021/jm9504722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Murata T, He S, Hangai M, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ ligands inhibit choroidal neovascularization. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2000;41(8):2309–2317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Colucciello M. Vision loss due to macular edema induced by rosiglitazone treatment of diabetes mellitus. Archives of Ophthalmology. 2005;123(9):1273–1275. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.9.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ryan EH, Jr., Han DP, Ramsay RC, et al. Diabetic macular edema associated with glitazone use. Retina. 2006;26(5):562–570. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200605000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kirch W, Horn B, Schweizer J. Comparison of angiotensin II receptor antagonists. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2001;31(8):698–706. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2001.00871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pershadsingh HA. Treating the metabolic syndrome using angiotensin receptor antagonists that selectively modulate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ . International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 2006;38(5-6):766–781. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kurtz TW. Treating the metabolic syndrome: telmisartan as a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ activator. Acta Diabetologica. 2005;42(supplement 1):s9–s16. doi: 10.1007/s00592-005-0176-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cianchetti S, Del Fiorentino A, Colognato R, Di Stefanoa R, Franzonic F, Pedrinellia R. Anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant properties of telmisartan in cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis. 2008;198(1):22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Shao J, Nangaku M, Inagi R, et al. Receptor-independent intracellular radical scavenging activity of an angiotensin II receptor blocker. Journal of Hypertension. 2007;25(8):1643–1649. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328165d159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gohlke P, Weiss S, Jansen A, et al. AT1 receptor antagonist telmisartan administered peripherally inhibits central responses to angiotensin II in conscious rats. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2001;298(1):62–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kliewer SA, Xu HE, Lambert MH, Willson TM. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: from genes to physiology. Recent Progress in Hormone Research. 2001;56:239–263. doi: 10.1210/rp.56.1.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Berger J, Moller DE. The mechanisms of action of PPARs. Annual Review of Medicine. 2002;53:409–435. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.53.082901.104018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Berger JP, Petro AE, Macnaul KL, et al. Distinct properties and advantages of a novel peroxisome proliferator-activated protein γ selective modulator. Molecular Endocrinology. 2003;17(4):662–676. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Oberfield JL, Collins JL, Holmes CP, et al. A peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ ligand inhibits adipocyte differentiation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(11):6102–6106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.McKenna NJ, O'Malley BW. Minireview: nuclear receptor coactivators—an update. Endocrinology. 2002;143(7):2461–2465. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.7.8892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.de Gasparo M, Catt KJ, Inagami T, Wright JW, Unger T. International union of pharmacology. XXIII. The angiotensin II receptors. Pharmacological Reviews. 2000;52(3):415–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wagner J, Danser AHJ, Derkx FH, et al. Demonstration of renin mRNA, angiotensinogen mRNA, and angiotensin converting enzyme mRNA expression in the human eye: evidence for an intraocular renin-angiotensin system. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 1996;80(2):159–163. doi: 10.1136/bjo.80.2.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Danser AHJ, van den Dorpel MA, Deinum J, et al. Renin, prorenin, and immunoreactive renin in vitreous fluid from eyes with and without diabetic retinopathy. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1989;68(1):160–167. doi: 10.1210/jcem-68-1-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Danser AH, Derkx FH, Admiraal PJ, Deinum J, de Jong PT, Schalekamp MA. Angiotensin levels in the eye. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 1994;35(3):1008–1018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Funatsu H, Yamashita H, Nakanishi Y, Hori S. Angiotensin II and vascular endothelial growth factor in the vitreous fluid of patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2002;86(3):311–315. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.3.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Senanayake P, Drazba J, Shadrach K, et al. Angiotensin II and its receptor subtypes in the human retina. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2007;48(7):3301–3311. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wilkinson-Berka JL. Angiotensin and diabetic retinopathy. International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 2006;38(5-6):752–765. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Otani A, Takagi H, Oh H, et al. Angiotensin II-stimulated vascular endothelial growth factor expression in bovine retinal pericytes. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2000;41(5):1192–1199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Castellon R, Hamdi HK, Sacerio I, Aoki AM, Kenney MC, Ljubimov AV. Effects of angiogenic growth factor combinations on retinal endothelial cells. Experimental Eye Research. 2002;74(4):523–535. doi: 10.1006/exer.2001.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Paques M, Massin P, Gaudric A. Growth factors and diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes & Metabolism. 1997;23(2):125–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pinto CC, Silva KC, Biswas SK, Martins N, Lopes de Faria JB, Lopes de Faria JM. Arterial hypertension exacerbates oxidative stress in early diabetic retinopathy. Free Radical Research. 2007;41(10):1151–1158. doi: 10.1080/10715760701632816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Silva KC, Pinto CC, Biswas SK, Souza DS, Lopes de Faria JB, Lopes de Faria JM. Prevention of hypertension abrogates early inflammatory events in the retina of diabetic hypertensive rats. Experimental Eye Research. 2007;85(1):123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wong TY, Mitchell P. The eye in hypertension. The Lancet. 2007;369(9559):425–435. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60198-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Pershadsingh HA. Telmisartan, PPAR-γ and retinal neovascularization. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2006 Feb; Letter to the Editor, http://www.iovs.org/cgi/eletters/46/3/1078. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Derosa G, Cicero AFG, D'Angelo A, et al. Telmisartan and irbesartan therapy in type 2 diabetic patients treated with rosiglitazone: effects on insulin-resistance, leptin and tumor necrosis factor-α . Hypertension Research. 2006;29(11):849–856. doi: 10.1291/hypres.29.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Derosa G, Fogari E, D'Angelo A, et al. Metabolic effects of telmisartan and irbesartan in type 2 diabetic patients with metabolic syndrome treated with rosiglitazone. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 2007;32(3):261–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2007.00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sugimoto K, Qi NR, Kazdová L, Pravenec M, Ogihara T, Kurtz TW. Telmisartan but not valsartan increases caloric expenditure and protects against weight gain and hepatic steatosis. Hypertension. 2006;47(5):1003–1009. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000215181.60228.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Geroski DH, Edelhauser HF. Transscleral drug delivery for posterior segment disease. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2001;52(1):37–48. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00193-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Myles ME, Neumann DM, Hill JM. Recent progress in ocular drug delivery for posterior segment disease: emphasis on transscleral iontophoresis. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2005;57(14):2063–2079. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Hsu J. Drug delivery methods for posterior segment disease. Current Opinion in Ophthalmology. 2007;18(3):235–239. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e3281108000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.van Leeuwen R, Ikram MK, Vingerling JR, Witteman JCM, Hofman A, de Jong PT. Blood pressure, atherosclerosis, and the incidence of age-related maculopathy: the Rotterdam Study. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2003;44(9):3771–3777. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Klein R, Klein BE, Tomany SC, Cruickshanks KJ. The association of cardiovascular disease with the long-term incidence of age-related maculopathy: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2003;110(6):1273–1280. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00599-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Nissen SE, Wolski K. Effect of rosiglitazone on the risk of myocardial infarction and death from cardiovascular causes. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;356(24):2457–2471. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Home PD, Pocock SJ, Beck-Nielsen H, et al. Rosiglitazone evaluated for cardiovascular outcomes—an interim analysis. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357(1):28–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Lago RM, Singh PP, Nesto RW. Congestive heart failure and cardiovascular death in patients with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes given thiazolidinediones: a meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. The Lancet. 2007;370(9593):1129–1136. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61514-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Erdmann E, Dormandy JA, Charbonnel B, et al. The effect of pioglitazone on recurrent myocardial infarction in 2,445 patients with type 2 diabetes and previous myocardial infarction: results from the PROactive (PROactive 05) study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007;49(17):1772–1780. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Dormandy JA, Charbonnel B, Eckland DJ, et al. Secondary prevention of macrovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes in the PROactive Study (PROspective pioglitAzone Clinical Trial In macroVascular Events): a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2005;366(9493):1279–1289. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67528-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Zhang F, Lavan BE, Gregoire FM. Selective modulators of PPAR-γ activity: molecular aspects related to obesity and side-effects. PPAR Research. 2007;2007:7 pages. doi: 10.1155/2007/32696. Article ID 32696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Sjølie AK, Porta M, Parving HH, et al. The DIabetic REtinopathy Candesartan Trials (DIRECT) Programme: baseline characteristics. Journal of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System. 2005;6(1):25–32. doi: 10.3317/jraas.2005.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]