Abstract

Objectives

Cervical cancer is the leading gynecological malignancy worldwide, and the incidence of this disease is very high in American Indian women. Infection with the Human Papillomavirus (HPV) is responsible for more than 95% of cervical squamous carcinomas. Therefore, the main objective of this study was to analyze oncogenic HPV infections in American Indian women residing in the Northern Plains.

Methods

Cervical samples were collected from 287 women attending a Northern Plains American Indian reservation outpatient clinic. DNA was extracted from the cervical samples and HPV specific DNA were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the L1 consensus primer sets. The PCR products were hybridized with the Roche HPV Line Blot assay for HPV genotyping to detect 27 different low and high-risk HPV genotypes. The chi-square test was performed for statistical analysis of the HPV infection and cytology diagnosis data.

Results

Of the total 287 patients, 61 women (21.25%) tested positive for HPV infection. Among all HPV-positive women, 41 (67.2%) were infected with high-risk HPV types. Of the HPV infected women, 41% presented with multiple HPV genotypes. Additionally, of the women infected with oncogenic HPV types, 20 (48.7%) were infected with HPV 16 and 18 and the remaining 21 (51.3%) were infected with other oncogenic types (i.e., HPV59, 39, 73). Women infected with oncogenic HPV types had significantly higher (p=0.001) abnormal Papanicolaou smear tests (Pap test) compared to women who were either HPV negative or positive for non-oncogenic HPV types. The incidence of HPV infection was inversely correlated (p<0.05) with the age of the patients, but there was no correlation (p=0.33) with seasonal variation.

Conclusions

In this study, we observed a high prevalence of HPV infection in American Indian women residing on Northern Plains Reservations. In addition, a significant proportion of the oncogenic HPV infections were other than HPV16 and 18.

Keywords: Human Papillomavirus, American Indian, Northern Plains, Cervical cancer, Cervical cancer diagnosis

Introduction

Statistical analyses released from the World Health Organization (WHO) suggest that cervical cancer is the second most common cancer in women worldwide [1–3]. It is estimated that each year approximately 493,000 new cases are diagnosed and 274,000 women die from cervical cancer worldwide [4]. The American Cancer Society estimates that in 2006, there will be 10,370 new diagnosed cases of cervical carcinoma and 3,710 deaths associated with cervical cancer in the United States alone [5]. The incidence of cervical carcinoma is substantially higher among women of low socioeconomic status. Although Pap smear screening has decreased the incidence of cervical cancer in the United States, there are still pockets of the population, such as the American Indian women of the Northern Plains, that have a significantly higher rate of cervical cancer [6, 7].

In the Northern Plains, the American Indian population is comprised of Lakota, Mandan, Omaha, and Chippewa tribes that reside in North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota, Nebraska, and Iowa. This population suffers from significant medical problems including cancer, diabetes, high infant mortality, alcoholism, and other chronic illnesses [8, 9]. Smoking rates and the incidence of sexually-transmitted infections are some of the highest in the country [9]. In addition, the women of this population suffer from high incidence of cervical carcinoma, which is a leading cause of cancer mortality in American Indian women [9]. There are marked regional differences in cervical cancer mortality rates among American Indian women in the United States. The Indian Health Service (IHS) of the Aberdeen area has calculated a female age-adjusted cervical cancer mortality rate of 15.6 per 100,000 people, which is 5 times that of the U.S. rate of 3.0 per 100,000 people [10]. While it is unclear why the cervical cancer mortality rate is so high in this area, the known risk factors for cervical carcinoma include multiparity, smoking, immunosuppression, poor nutrition, and Human Papillomavirus (HPV) infection [11]. However, the most important risk factors for cervical cancer are the persistence of an oncogenic HPV infection and a lack of timely screening [12–14].

The presence of HPV DNA in cervical tissues has implicated HPV as a causative agent in genital condylomatas, in lower female genital tract intraepithelial neoplasias, such as cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), and in invasive cervical carcinomas [15]. It has been demonstrated that HPV DNA can be detected in approximately 99% of all invasive cervical cancers [16]. In addition, HPV DNA is almost always present in condylomatas and high-grade dysplasias, such as CIN III [17]. HPV types 6 and 11 are known to induce exophytic condylomatas affecting the anogenital mucosa and lower vagina [18]. A subset of HPV types (types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, and 68) are regarded as oncogenic, or high-risk, HPV viral types. This subset represents the predominant HPV genotypes detected in high-grade intraepithelial lesions (CIN II and III) and in carcinomas of the lower female genital tract [16, 17, 19].

A basic understanding of the HPV epidemiology is required in order to understand the role of various HPV types in the development of cervical cancer and to design effective vaccine strategies against the virus. Different populations may harbor varying HPV genotypes in the genital tract [16]. Thus far, the Northern Plains American Indian population has not been studied regarding their prevalence of HPV genotypes. Before utilizing HPV vaccines for a particular population, it is imperative to have relevant HPV genotyping data in order to provide an optimal vaccine for providing the best possible care for that population. This study provides the baseline data that will be accessible to insure that this population can be appropriately included in vaccine trials in the future.

Materials and methods

Sample acquisition and methods for Papanicolaou tests

Over a two and one-half year time period, 287 cervical samples were collected from women attending a Northern Plains American Indian reservation outpatient clinic. An appropriate Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained prior to sample collection. Patients presenting at the gynecology clinic for a routine physical examination volunteered to participate in this study. The number of patients asked to participate varied because of time constraints of the practicing health care providers. Several times, the samples were collected during a general health care screening program that provided Pap tests and mammograms. A history collection and physical examination were performed on the patient and a conventional or liquid-based Pap smear was obtained. Cervical samples were obtained using a plastic broom-like collection device (Hardwood Product Co, Guilford, ME). For conventional Pap smear, samples were prepared on a glass slide. However, for the liquid based cytology, the collection device was rinsed into a vial of PreservCyt solution (Cytyc) and slides were prepared according to the procedure described earlier [20]. The Paps were diagnosed using the Bethesda system (TBS) in which the terms atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS), squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL, HSIL) are used [21].

Line Blot assay

An additional cervical sample was obtained for Line Blot assay with the Digene Hybrid Capture cervical specimen collector (Digene Diagnostics, Gaithersburg, MD) and was immediately placed in the specimen transport medium and stored at −20 °C. Specimens were batch shipped to our laboratory every two weeks for HPV analysis.

DNA isolation from cervical samples

Upon receipt, cervical samples were processed for DNA extraction according to the protocol previously described by Gravitt et al, 1998 [22]. The integrity of the extracted DNA was confirmed utilizing standard 1% agarose gel electrophoresis followed by staining with ethidium bromide. The DNA extracts were stored at −20 °C until amplification by polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and reverse hybridization for HPV genotyping

HPV DNA was amplified using the L1 consensus primer system (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Negative and positive controls were provided in the kit for PCR. Additionally, DNA samples obtained from HPV infected (Hela and Caski) and uninfected (C33-A) cervical cancer cell lines were also used as positive and negative controls. Each amplification contained 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 4mM MgCl2, 200 mM (each) dCTP dGTP and dATP, 600 µM dUTP, 7.5 U of AmpliTaq Gold, 100pmol each PGMY09 and PGMY11 primer blends, 5 pmol B PC04, 5 pmol B GH20 and 5 to 10 µl of digested sample. The reactions were amplified using a iCycler™ thermocycling system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). For HPV genotyping, 75µl of PCR product was denatured in 75 µl of 1.6% (w/w) NaOH solution and biotinylated. HPV genotyping strips were pre-incubated with hybridization buffer (4X SSPE [1X SSPE is 0.18 M NaCl, 10mM NaH2PO4, and 1mM EDTA] in 0.5% SDS) pre-warmed to 53 °C. Following the pre-incubation step, the denatured, biotinylated product was added to the strips and incubated in a shaking water bath at 53 °C for 30 minutes. The strips were washed with washing buffer (1 X SSPE, 0.1% SDS) followed by incubation with the streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (1:1000 dilution) at room temperature for 30 minutes. Hybridization was detected by incubating the strips in a 4:1 mixture of substrate A (hydrogen peroxide in sodium citrate buffer) and substrate B (3, 3’, 5, 5’-tetramethylbenzidine in dimethylformamide) for 5 minutes, followed by a water rinse and storage in citrate buffer. Interpretation of the strips (line blots) was performed using a labeled acetate overlay with lines indicating the position of each probe relative to a reference mark on the strip indicating high and low risk types.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Version 10.0 for Windows. The chi-square test was performed to assess the statistical significance of differences in the prevalence of HPV infection and in the frequency of multiple infections among different age groups. P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

High prevalence of HPV infection in American Indian women

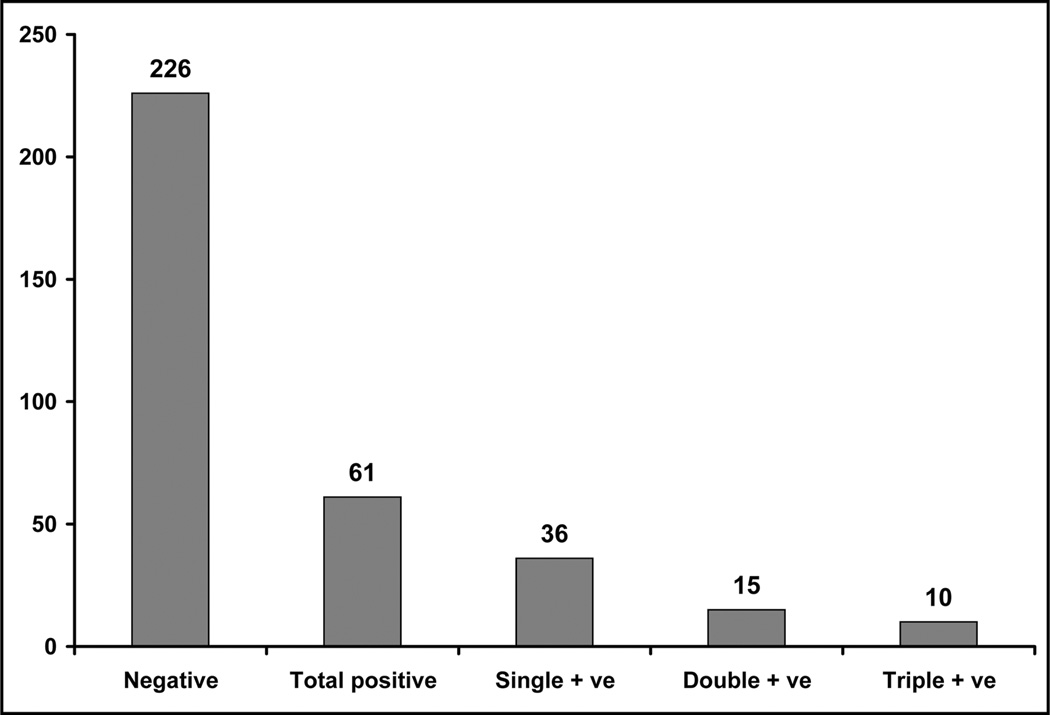

The participants included in this study were sexually active with no previous histological diagnosis or treatment and were seeking cervical cancer screening. In this study, we screened 287 cervical samples, collected from women residing on Northern Plains American Indian Reservations, to detect HPV infection. The age range of patients was 18–75 years, with an average age of 29.6 years at the time of testing. Of the total 287 patients, 61 women (21.25%) tested positive for HPV infection (Table 1A). Among all HPV-positive patients, 43% (25/61) exhibited multiple HPV infections, which were characterized by one patient being infected with two or more HPV types at the same time. Of the 61 HPV-positive women, 36, 15, and 10 women were positive for single, double, or triple infections, respectively (Fig. 1).

Table 1A.

Correlation between HPV infection and Pap smear test in American Indian women (n=287) of the Northern Plains

| HPV Status | Number of Women (Percentage of Total Women) | Pap Test Status at Sampling Time | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | ASCUS | SIL | ||||

| L | H | |||||

| HPV− | 226 (78.7%) | 195 | 22 | 4 | 1 | 0.001* |

| HPV+ | 61 (21.3%) | 31 | 13 | 8 | 9 | |

| Oncogenic HPV+ | 41 (14.3%) | 15 | 10 | 7 | 9 | 0.001** |

| Non-oncogenic HPV+ | 20 (7.0%) | 16 | 3 | 1 | 0 | |

Note: Pap smear data of four patients was not available

N=normal Pap, ASCUS= Atypical Squamous Cells of Undetermined Significance, SIL= Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion (H=High grade and L=low grade)

Statistical correlation between HPV infectivity and abnormal Pap test, p value <0.05 considered significant

Statistical correlation between high oncogenic HPV infectivity and abnormal Pap test, p value <0.05 considered significant

Fig. 1.

Graphical presentation of the distribution of single, double and multiple HPV infections among all HPV-positive American Indian women of the Northern Plains.

American Indian women exhibited presence of uncommon oncogenic HPV types

Among all HPV-infected women in our study, 67.2% (41/61) of the women were infected with oncogenic HPV types, and 32.8% (20/61) of the women were positive for non-oncogenic HPV types. The main types of HPV types identified in women on Northern Plains American Indian Reservations are shown in Table 1B. In American Indian women, HPV 16 was present in the most cases (n=13), and HPV 59 (n=8) was the second most prevalent HPV infection. Of the women infected with oncogenic HPV types, HPV 16/18 were collectively present in 20 women (48.7%); the remaining 21 women (51.2%) were positive for other oncogenic types of HPV. Overall, while the prevalence of oncogenic HPV types is similar to the pattern identified in other populations, where HPV 16 was reported as the most common oncogenic HPV types [16], women in our study had a higher prevalence of certain oncogenic types (notably HPV 59, 39 and 73). The degree of cytological abnormality in the Pap smear was significantly (p=0.001) correlated with the HPV infection (Table 1A). The incidence of ASCUS and SIL (LSIL, HSIL) in the Pap test was significantly (p=0.001) higher in women who were infected with high-risk HPV types compared to HPV negative or low-risk HPV types infected women (Table 1A).

Table 1B.

Incidence and frequency of oncogenic and non-oncogenic HPV genotypes and respective Pap smear test in American Indian women (n=287) of the Northern Plains

| HPV Genotype | Single Infection | Multiple Infection | Number of Women (Percentage of Total Women) | Percentage of Total (n=61) HPV Infected Women | Pap Test Status at Sampling Time | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | ASCUS | SIL | ||||||

| L | H | |||||||

| Oncogenic HPV types | ||||||||

| 16 | 3 | 10 | 13 (4.5%) | 21.3% | 5 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| 18 | 2 | 5 | 7 (2.4%) | 11.5% | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 59 | 2 | 6 | 8 (2.8%) | 13.1% | 3 | 2 | 3 | 0 |

| 39 | 4 | 3 | 7 (2.4%) | 11.5% | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 73 | 2 | 3 | 5 (1.7%) | 8.2% | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 58 | 2 | 2 | 4 (1.4%) | 6.6% | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 45 | 1 | 4 | 5 (1.7%) | 8.1% | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 31 | 1 | 3 | 4 (1.4%) | 6.6% | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 68 | 0 | 2 | 2 (0.7%) | 3.3% | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 56 | 0 | 2 | 2 (0.7%) | 3.3% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 52 | 0 | 2 | 2 (0.7%) | 3.3% | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 51 | 0 | 2 | 2 (0.7%) | 3.3% | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 82 | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.3%) | 1.6% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 35 | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.3%) | 1.6% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 66 | 2 | 0 | 2 (0.7%) | 3.3% | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Non-oncogenic HPV types | ||||||||

| 11 | 3 | 3 | 6 (2.1%) | 9.8% | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| 53 | 1 | 4 | 5 (1.7%) | 8.2% | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 72 | 3 | 1 | 4 (1.4%) | 6.6% | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 83 | 2 | 0 | 2 (0.7%) | 3.3% | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 71 | 2 | 0 | 2 (0.7%) | 3.3% | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 62 | 2 | 0 | 2 (0.7%) | 3.3% | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 61 | 1 | 1 | 2 (0.7%) | 3.3% | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 26 | 0 | 2 | 2 (0.7%) | 3.3% | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cand89 | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.3%) | 1.6% | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 81 | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.3%) | 1.6% | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 70 | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.3%) | 1.6% | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 67 | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.3%) | 1.6% | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 55 | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.3%) | 1.6% | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 42 | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.3%) | 1.6% | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Note: Because of multiple infections, the sum will exceed the total number of women

N=normal Pap, ASCUS= Atypical Squamous Cells of Undetermined Significance, SIL= Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion (H=High grade and L=low grade)

Higher prevalence of HPV infection in younger women

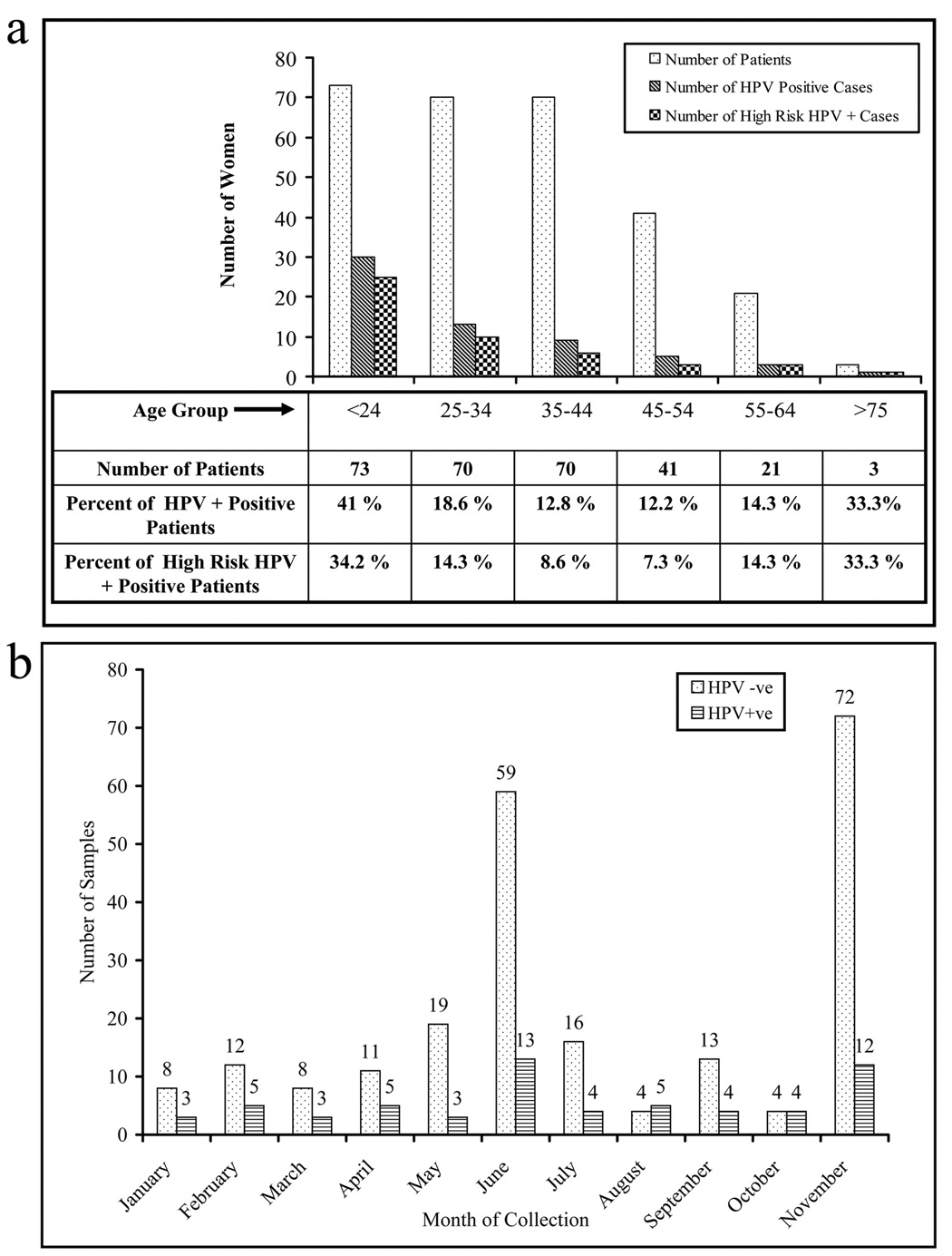

In order to analyze the correlation between the frequency of HPV infection and various age groups, all recruited women were divided into seven groups according to their age. The incidence of HPV infection was inversely correlated with the age. In younger women (< 24 years) HPV infection was significantly higher (41%, P<0.005) compared to all other age groups (Fig. 2a). In contrast, none of the women from the 65–74 age group exhibited HPV infection (Fig. 2a). Previous studies have indicated a seasonal correlation of HPV infection [23, 24]; however, in our study there was no correlation (p=0.33) between HPV infection and seasonal variation (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

The presence of HPV infection with age and seasonal variations. (a) The incidence of HPV infection was higher in younger women (<24 years) than in the other age groups. (b) Association of HPV infection with seasonal variations. There was no significant association between the seasonal variations and HPV infection in American Indian women of the Northern Plains.

Discussion

In Northern Plains American Indian women, cervical cancer has become a significant public health issue. In fact, as mentioned earlier, the IHS of the Aberdeen area has calculated a female age-adjusted cervical cancer-associated death rate five times higher than that of the average U.S. rate. This is primarily due to a lack of routine cervical cancer screening in a subset of the population. Additionally, the results of our study clearly demonstrate that the American Indian population of the Northern Plains suffers from an inordinate amount of HPV infection. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first community-based study to investigate the prevalence of HPV infection in American Indian women residing on the Northern Plains. In addition, our study also revealed the existence of several uncommon oncogenic, or high risk, HPV types in the American Indian population. Results of this study suggest that the high incidence of HPV infection leads to a high incident rate of cervical carcinoma (the leading cause of cancer-related deaths) in American Indian women of this area. This data also demonstrate that there are marked regional differences in HPV prevalence among women in the United States.

To conduct this community-based study, we collected cervical samples from 287 American Indian women residing on Northern Plains Reservations. Although the number of women who participated in this study may seem low, it is a substantial portion of the female American Indian population of the Northern Plains. Our results indicate a high prevalence of HPV infection. Additionally, a significant proportion of the HPV-infected women were positive for oncogenic HPV types. Fifty two percent of the women were positive for uncommon oncogenic HPV types and 48% of the women in this population were positive for HPV16 and HPV18, the most commonly found high risk HPV genotypes in cervical cancer patients. The presence of these uncommon oncogenic HPV types may be a crucial factor that contributes to the increased cervical cancer incidence and mortality in this population. The mean age of HPV-positive patients was significantly lower when compared to the HPV-negative women. Additionally, younger women have a higher rate of multiple infections compared to other age groups (data not shown). These findings are consistent with the findings of other investigators in different other geographic populations [16].

In Table 2, we compared the pattern of HPV infection with varying age groups and with the frequency of single and multiple infections in women from different geographical locations around the world, including the Northern Plains. In terms of the HPV prevalence and rates of multiple infections, the Northern Plains women are most similar to Sub-Saharan African women (Table 2 adopted from Clifford et al., a meta analysis of HPV prevalence in different populations) [16]. A Netherlands study (Hrushesky et. al) showed a seasonal correlation with HPV infection [24]. According to their study, there was a positive correlation between the summer time (UV light) and HPV infectivity. In our study, we did not observe a correlation between HPV infection and the time of sample collection. Our sample collection percentages ranged from 2.8% in October to 29.2% for November. In our study, the number of HPV-positive patients was higher in months where more samples were collected. These higher collection months generally took place during Cervical Cancer screening campaigns.

Table 2.

The comparative prevalence of HPV infection and the pattern of single and multiple infections in Sub-Saharan African, Asian, European and Northern Plains American Indian women. (Adapted from Clifford et al., 2005) [15]

| Age-group (years) | Multiple HPV | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area | 15–24 | 25–34 | 35–44 | 45–54 | 55–64 | 65–74 | Total | Single | 2 | ≥ 3 | Any HPV |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 113 | 174 | 125 | 172 | 151 | 91 | 826 | 16.5% | 5% | 3.3% | 24.7% |

| Asia | 796 | 1578 | 1331 | 1037 | 881 | 477 | 6100 | 6.3% | 3.2% | 0.6% | 8.2% |

| South America | 669 | 1088 | 871 | 442 | 322 | 154 | 3546 | 9.4% | 2.8% | 1.6% | 13.9 |

| Europe | 176 | 795 | 1379 | 1505 | 1064 | 222 | 5141 | 3.7% | .7% | 0.2% | 4.5% |

| Northern Plains | 73* | 70 | 70 | 41 | 21 | 9 | 284 | 12.5% | 5.3% | 3.5% | 21.1 |

| All areas | 1827 | 3705 | 3776 | 3197 | 2439 | 953 | 15897 | 6.8% | 2.4% | 0.9% | 9.4% |

Data collected on 18–24 year olds, inclusive.

In order to effectively utilize HPV vaccine(s) in American Indian women on the Northern Plains, it is imperative to determine the HPV prevalence and genotypes of this population. Therefore, in addition to determining the frequency of HPV infection, we also investigated the HPV genotypes of this population. In most studied populations, HPV16 and HPV 18 were the most predominant oncogenic genotypes. In the American Indian women of the Northern Plains, these two genotypes (HPV16 and HPV 18) were present in 48% of the oncogenic infections. The remaining 52% of women were infected with other oncogenic HPV genotypes, such as HPV59, the second most predominant genotype. In conclusion, this study suggests two main points: 1) there is a high HPV prevalence and spectrum of oncogenic genotypes in American Indian women of the Northern Plains. 2) While the current HPV16/18 vaccine will be beneficial, our study suggests that a substantial number of other high-risk oncogenic HPV types may cause cervical cancer in American Indian women of the Northern Plains.

Acknowledgements

The authors thankfully acknowledge the physicians and nursing staff of the general gynecologic clinics on Northern Plains American Indian Reservations for providing their constant support in cervical sample collections. We thank Diane Maher, PhD, and Cathy Christopherson for their careful review of the manuscript. We also thank the Director of Indian Health Services for providing access to collect the cervical samples. This study was supported by an American Cancer Society Midwest Division grant and by an NIH “Spirit of Eagles” grant.

This research was supported by an American Cancer Society Midwest Division grant as well as a NIH “Spirit of Eagles” grant.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pisani P, Bray F, Parkin DM. Estimates of the world-wide prevalence of cancer for 25 sites in the adult population. Int J Cancer. 2002;97:72–81. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pisani P, Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J. Estimates of the worldwide mortality from 25 cancers in 1990. Int J Cancer. 1999;83:18–29. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990924)83:1<18::aid-ijc5>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iihara K, et al. Prognostic significance of transforming growth factor alpha in esophageal carcinoma. Cancer. 1993;71:2902–2909. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930515)71:10<2902::aid-cncr2820711004>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cancer Facts and Figures. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cobb N, Paisano R. Cancer mortality among American Indians and Alaska Natives in the United States: regional differences in Indian Health. Rockville (MD): Indian Health Service; 1997. pp. 1989–1993. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leman RF, Espey D, Cobb N. Invasive cervical cancer among American Indian women in the Northern Plains, 1994–1998: incidence, mortality, and missed opportunities. Public Health Rep. 2005;120:283–287. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cancer in South Dakota. Pierre: South Dakota Department of Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burhansstipanov L. Continuing Educational Module. Denver, CO: Native Elder Health Care Resouce Center; 1996. Cancer among native American. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shalala DE, Trujillo MH, Harry RH, Skupien MB, D'Angelo AJ. Regional Differences in Indian Health. Indian Health Service; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoskins WJ, Perez CA, Young RC, editors. Principles and Practice of Gynecologic Oncology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Damasus-Awatai G, Freeman-Wang T. Human papilloma virus and cervical screening. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2003;15:473–477. doi: 10.1097/00001703-200312000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reid J. Women's knowledge of Pap smears, risk factors for cervical cancer, and cervical cancer. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2001;30:299–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castle PE, Shields T, Kirnbauer R, Manos MM, Burk RD, Glass AG, Scott DR, Sherman ME, Schiffman M. Sexual behavior, human papillomavirus type (HPV 16) infection, and HPV 16 seropositivity. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29:182–187. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200203000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castle PE, Hillier SL, Rabe LK, Hildesheim A, Herrero R, Bratti MC, Sherman ME, Burk RD, Rodriguez AC, Alfaro M, Hutchinson ML, Morales J, Schiffman M. An association of cervical inflammation with high-grade cervical neoplasia in women infected with oncogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:1021–1027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clifford GM, Gallus S, Herrero R, Munoz N, Snijders PJ, Vaccarella S, Anh PT, Ferreccio C, Hieu NT, Matos E, Molano M, Rajkumar R, Ronco G, de Sanjose S, Shin HR, Sukvirach S, Thomas JO, Tunsakul S, Meijer CJ, Franceschi S. Worldwide distribution of human papillomavirus types in cytologically normal women in the International Agency for Research on Cancer HPV prevalence surveys: a pooled analysis. Lancet. 2005;366:991–998. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67069-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richardson H, Franco E, Pintos J, Bergeron J, Arella M, Telier P. Determinants of low-risk and high-risk cervical human papillomavirus infectionsn in Montreal University students. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2000;27:79–86. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200002000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Franco E, editor. Obstetrics and Gynecology clinics of North America: Human Papillomavirus I. Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Sunders Company; 1996. Epidemiology of anogenital warts and cancer. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.ZurHausen H, Villiers Ed. Human papillomavirus. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1994;48:427–447. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biscotti CV, O'Brien DL, Gero MA, Gramlich TL, Kennedy AW, Easley KA. Thin-layer Pap test vs. conventional Pap smear. Analysis of 400 split samples. J Reprod Med. 2002;47:9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Apgar BS, Zoschnick L, Wright TC., Jr The 2001 Bethesda System terminology. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:1992–1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gravitt PE, Peyton CL, Apple RJ, Wheeler CM. Genotyping of 27 human papillomavirus types by using L1 consensus PCR products by a single-hybridization, reverse line blot detection method. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3020–3027. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.10.3020-3027.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hrushesky WJ, Sothern RB, Rietveld WJ, Du Quiton J, Boon ME. Season, sun, sex, and cervical cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1940–1947. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hrushesky WJ, Sothern RB, Rietveld WJ, Du-Quiton J, Boon ME. Sun exposure, sexual behavior and uterine cervical human papilloma virus. Int J Biometeorol. 2006;50:167–173. doi: 10.1007/s00484-005-0006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]