Adult Schistosoma mansoni parasites live in the vasculature of their vertebrate hosts where they consume blood. Ingested blood proteins are degraded by a proteolytic cascade that includes aspartic and cysteine proteases [1-3]. These proteases are considered important potential drug targets [4]. One of the best characterized schistosome proteases is cathepsin B1 (SmCB1 or Sm31) which is a papain-like cysteine proteinase [5, 6]. This protein is expressed at high levels in the parasite gut after invasion of the vertebrate host by infectious forms called cercariae [7, 8]. SmCB1 is reported to be the most abundant cysteine peptidase activity measurable both in whole adult schistosome extracts and in gastrointestinal content extracts [3]. SmCB1 is also found in the cercarial caecum and protonephridia [9]. Like mammalian cathepsin B enzymes, SmCB1 is first synthesized as a larger precursor form which is proteolytically cleaved to yield a mature cathepsin B [10 - 13]. The gene for SmCB1 encodes a putative signal sequence, pro-region and catalytic domain. The native 38kDa SmCB1 zymogen is processed to a mature 31 kDa protein [12, 13].

A second schistosome protease that has been the subject of much study is the asparaginyl endopeptidase SmAE (also known as Sm32, or schistosome legumain) [2,6]. SmAE is expressed in cercarial protonephridia as well as in the parasite gut [9, 14]. Rather than directly digesting blood proteins in the gut, it has been proposed that SmAE is involved in the proteolytic activation of other endopeptidases that perform this function [15, 16]. SmAE orthologs in plants and mammals are involved in a variety of processing events such as the conversion of zymogens to their mature and biologically active forms [3]. In schistosomes, it has been hypothesized that one function of SmAE is to process native SmCB1 to its mature form [15, 17]. Considerable support for this hypothesis was presented following the expression of recombinant SmCB1 and SmAE in the yeast Pichia pastoris [16, 18]. Recombinant activated SmAE was shown to trans-process SmCB1 into its mature, catalytic form in vitro [3]. In the present study, our aim was to test the hypothesis that in vivo SmAE likewise processes SmCB1 into its active form. If this hypothesis is correct then the suppression of SmAE expression using RNA interference (RNAi) should lead to an accumulation of unprocessed SmCB1 and a corresponding diminution in mature cathepsin B protein and cathepsin B enzyme activity in treated parasites. Since we find that a substantial suppression in SmAE protein levels has no effect on SmCB1 processing or activity, we conclude that SmAE is not essential for SmCB1 activation in vivo.

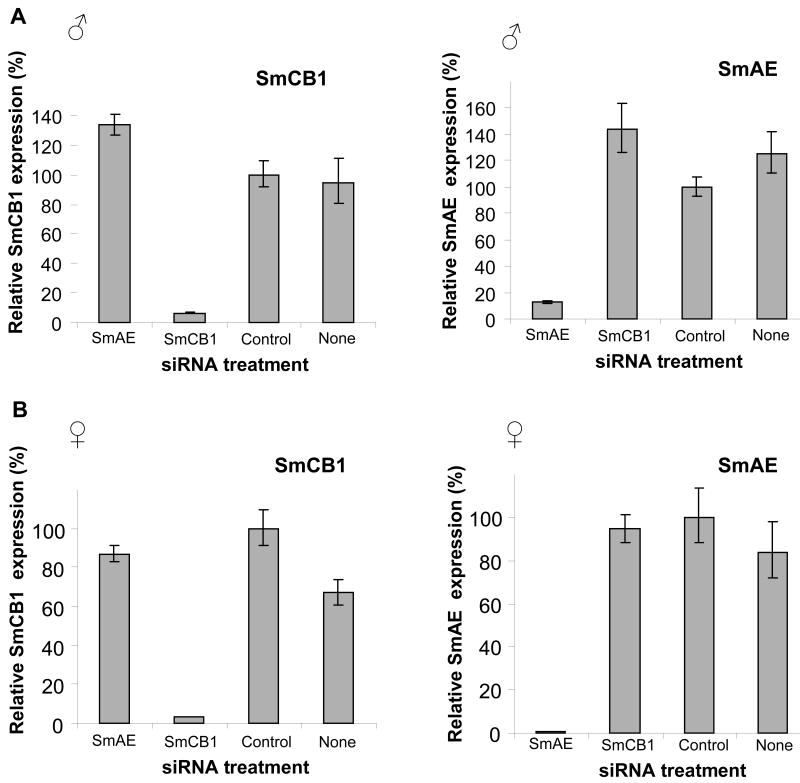

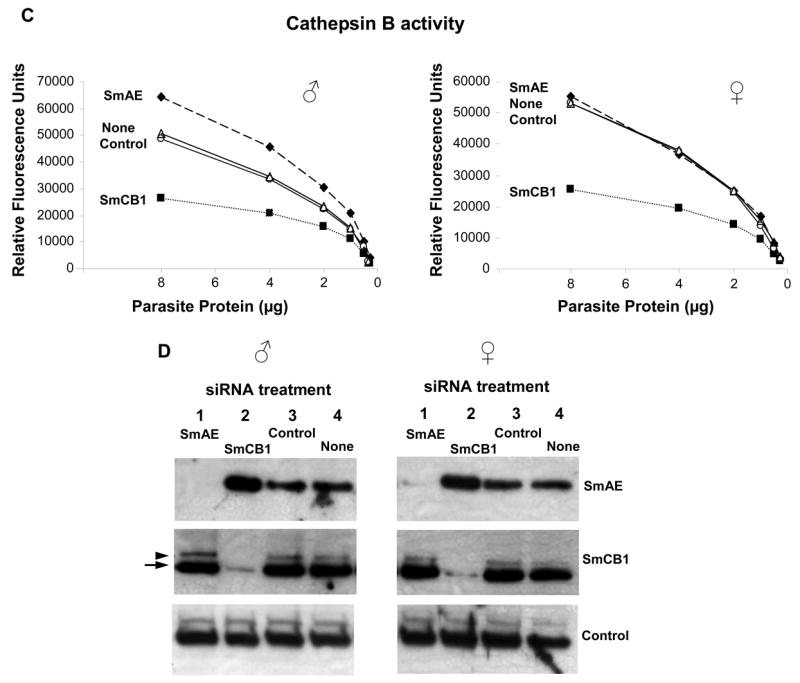

To test the hypothesis that SmAE is central to SmCB1 processing and activation, adult male schistosomes were first subjected to RNAi by exposure to either SmCB1 siRNA or SmAE siRNA or an irrelevant, non-schistosome siRNA. The siRNAs were synthesized commercially by Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT Inc., IA). The sequence of the SmCB1 siRNA is 5′-AAGCAAUGAGUGAUCGAAGCU-3′ (and spans position 370-391 of the cathepsin B mRNA). The SmAE siRNA sequence is 5′-AUACCAAAUACCAAGGCAACUAUCG -3′ (and spans position 1096-1118 of the SmAE mRNA). The control irrelevant siRNA is the off-the-shelf “DS Scrambled Neg” siRNA from IDT Inc., and this sequence does not exist in the S. mansoni genome [8]. Adult male and female parasites (15 per group) were electroporated with 10 μg of SmCB1, SmAE or control, siRNA in 100 μl electroporation buffer (Ambion, TX) as described [19]. Worms were then cultured for 7 days in complete RPMI medium, which was changed every two days. Following this treatment, the levels of expression of the SmCB1 and SmAE genes were assessed by quantitative real time-PCR, using alpha tubulin gene expression as the endogenous control, as previously described [8]. SmAE was detected using the following primers F5′-GGATTGTACAGAATCAGTCTATGAACAGT-3′, R5′-GAGTAGAAAAGTGCCCTCCAACT-3′ and probe 5′- FAM-TCACACTACAACAGGCTCC-3′. All other primers and probes are as described [8]. Results for SmCB1 gene suppression are shown in figure 1A and for SmAE gene suppression in figure 1B. In each group the target gene was specifically suppressed >90% relative to the other groups. Next, the impact of this suppression on cathepsin B enzyme activity was measured by adding serially diluted soluble extracts of siRNA-treated worms to a 200 μl reaction mixture containing 0.1 M sodium phosphate pH 6, 1 mM dithiothreitol and 20 μM of the fluorogenic substrate ZArg-Arg-NMec (Bachem, Inc.). After incubation at room temperature for 24 h in the dark, fluorescence emission due to hydrolysis of the substrate was measured using a Synergy HT spectrofluorometer (BIO-TEK Instruments, Inc.) at 360 nm excitation and 460 nm emission. Figure 1C illustrates the impact of SmCB1 or SmAE gene suppression on cathepsin B activity in the three groups. It is clear that parasite extracts derived from worms treated with SmCB1 siRNA have greatly diminished cathepsin B enzyme activity relative to the other treatment groups (Figure 1C). Other cathepsins whose genes were not targeted for suppression (e.g. SmCB2) likely contribute to the residual enzyme activity in the extracts of SmCB1 suppressed worms [20]. Of greater interest for the present study is the observation that extracts of worms treated with SmAE siRNA exhibit a cathepsin B activity profile comparable with that seen using extracts of control worms treated with an irrelevant siRNA (Figure 1C). This demonstrates that the substantial suppression of SmAE does not impact cathepsin B activation and is an indication that SmAE, contrary to expectations, is not central to the activation process.

Figure 1.

Suppression of SmCB1 and SmAE in 6-week old, adult male parasites 7 days after treatment with 10 μg SmCB1, SmAE or control siRNA. Relative SmCB1 (A) and SmAE (B) expression (mean ± S.E.) in the three treatment groups. C, Cathepsin B enzyme activity in protein extracts prepared from parasites treated with SmCB1, SmAE or control siRNA. D, Detection by western analysis of SmAE protein (top panel), SmCB1 protein (middle panel) and a control protein (SPRM1hc, bottom panel) in protein extracts prepared from parasites treated with SmAE (lane 1), SmCB1 (lane 2), or control (lane 3) siRNA. The arrow indicates the mature 31kDa cathepsin B protein and the arrowhead indicates the 38kDa unprocessed, procathepsin B.

Western blotting analysis was next undertaken in order to assess the impact of gene suppression on the protein levels of each target. For detection of SmCB1 and SmAE in siRNA-treated worms, 10 μg of soluble protein in 20 μl sample buffer was separated by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions, blotted onto PVDF membrane and blocked using detector block solution (KPL, Inc.) for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane was then probed overnight at 4°C with affinity purified rabbit immune-serum at 1:200 (directed against SmCB1 or SmAE recombinant protein [9] or against a control protein (SPRM1hc) [21]). Bound primary antibody was detected using horse radish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen, Inc.), diluted 1:5000, followed by incubation with the chemiluminescent substrate LumiGLO (KPL, Inc.) and membrane exposure to X-ray film.

The same membrane was probed three times to detect SmCB1, SmAE and control protein (SmPRM1hc, used as the loading control). For each re-use, the membrane was first incubated for 30 min with 2% SDS and 0.7% β-mercaptoethanol to strip bound antibody and was then washed in phosphate buffered saline for 30 min. The results of these western blot analyses are shown in figure 1D. The top panel shows that the suppression of SmAE gene expression resulted in a substantial diminution in SmAE protein levels such that the protein is undetectable in extracts of SmAE siRNA-treated parasites (Figure 1D, top panel, lane 1). In contrast, SmAE protein is easily detected in extracts of parasites treated with SmCB1 siRNA or with control, irrelevant siRNA, as determined by western blotting analysis (Figure 1D, top panel, lanes 2 and 3). The middle panel of figure 1D shows the levels of SmCB1 in all groups. As expected, the level of this protein in parasites treated with SmCB1 siRNA is diminished relative to the other groups (lane 2). Parasites treated with SmAE siRNA (lane 1) or with a control, irrelevant siRNA (lane 3) exhibit comparable levels of SmCB1 (Figure 1D, middle panel). Note that two forms of SmCB1 are detected; the major band (Figure 1D, arrow) represents the fully mature protein running at 31 kDa, while the minor band of higher molecular weight, (38 kDa, Figure 1D, arrowhead), represents the precursor, procathepsin B [13]. In parasite extracts virtually lacking SmAE (lane 1, Figure 1D), we detect no large accumulation of this immature, 38 kDa precursor form of SmCB1. These data show that, even in the absence of detectable SmAE, cathepsin B is fully processed (Figure 1D) and active (Figure 1C) and supports the assertion that SmAE does not activate SmCB1 in vivo. In the bottom panel, the amino acid permease protein SPRM1hc is detected in all extracts as a protein loading control to demonstrate that comparable levels of protein are present in each lane. Taken together, these data indicate that our original hypothesis is incorrect and that SmAE is not pivotal in the in vivo conversion of cathepsin B into its mature, active form. Our data show that cathepsin B is fully active in the absence of detectable SmAE.

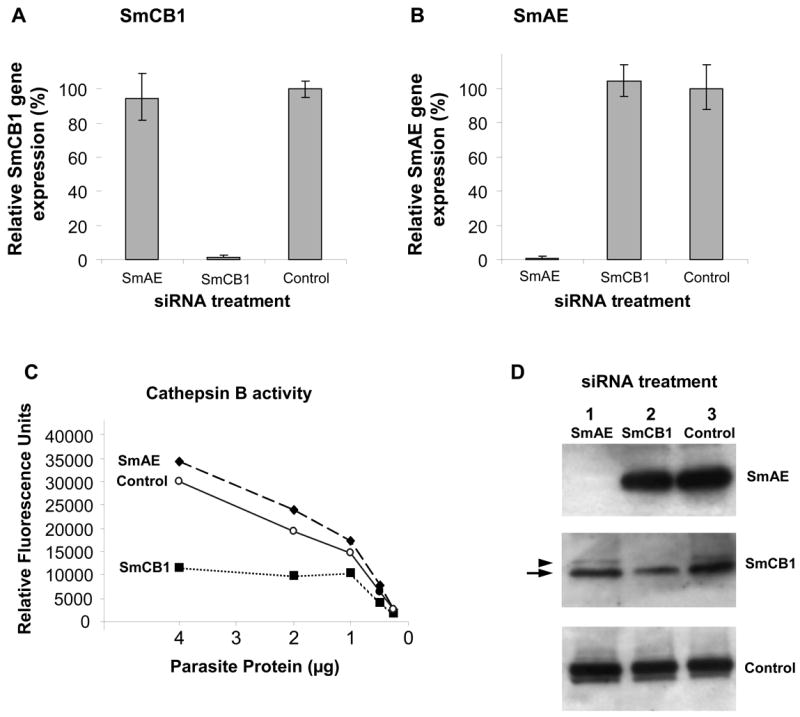

However, it could be argued that large amounts of SmAE present prior to the onset of suppression were responsible for the results seen. To test this notion, we repeated our analysis on worms that had been subjected to RNAi for a longer period of time – 15 days. In this experiment, both male and female worms were tested, and groups comprising parasites that were not treated with any siRNAs were included as additional controls. In agreement with results obtained 7 days after siRNA treatment, Figure 2 A and B show that substantial and specific suppression (>90%) of each target gene (SmCB1, left and SmAE, right) is also apparent in both males (A) and females (B), 15 days after siRNA treatment. As expected, cathepsin B activity is diminished in extracts of parasites subjected to SmCB1 suppression but not in extracts of the control groups, or in extracts of the group subjected to SmAE suppression (Figure 2C). This is the case for both male (left) and female (right) groups (Figure 2C). Western analysis of extracts of these parasites shows that SmAE levels are very low or undetectable in male or female worms treated with SmAE siRNA but not in the remaining groups (Figure 2D, top panels). In agreement with the cathepsin B activity measurements, substantially lower levels of SmCB1 protein are detected in extracts of parasites whose SmCB1 gene is suppressed (Figure 2D, middle panels, lanes 2). As in the earlier experiment, both the immature procathepsin B (arrowhead) and the mature enzyme (arrow) can be detected here also. In extracts of parasites treated with SmAE siRNA, which possess low or no SmAE protein, the vast majority of the SmCB1 detected is in the fully mature form (Figure 2D, middle panels, lanes 1) and is fully active (Figure 2C). It seems unlikely that trace amounts of SmAE are responsible for this conversion of procathepsin B into its more abundant, active form. Rather, the evidence strongly suggests that SmAE does not play an important role in cathepsin B zymogen processing and is not critical for activating SmCB1 in vivo. These data are in broad agreement with previous work in which SmAE gene expression was suppressed in 3-week-old male and female worms; extracts of these parasites exhibited a modest (∼20%) decline in cathepsin B activity [22] indicating that SmAE is not essential for cathepsin B1 activation. The fact that recombinant SmAE can trans-activate purified, recombinant SmCB1 under in vitro conditions [18] highlights the danger of extrapolating in vitro results to the in vivo situation. These results leave unclear both how SmCB1 is activated within living schistosomes, and the precise function of SmAE. Whether SmAE trans-activates other schistosome enzymes is unclear but this concept can now be tested using gene suppression in a manner similar to that described here for cathepsin B. It is possible that these results reflect redundancy in the activation pathway of SmCB1; perhaps SmAE does activate SmCB1 in vivo but, in its absence, other proteases perform this function. It appears unlikely that a second legumain enzyme fulfills this role, since earlier work showed that 6 days after suppressing SmAE gene expression in young adult parasites, there was an almost complete loss (98% decline) of legumain activity in extracts of these worms [22].

Figure 2.

Suppression of SmCB1 and SmAE in adult male parasites and adult female parasites 15 days after treatment with 10 μg SmCB1, SmAE, control or no siRNA. Relative SmCB1 and SmAE expression (mean ± S.E.) in the male groups (A) and the female groups (B). C, Cathepsin B enzyme activity in protein extracts prepared from male parasites (left) or female parasites (right) treated with SmCB1, SmAE, control or no siRNA. D, Detection by western analysis of SmAE protein (top panel), SmCB1 protein (middle panel) and a control protein (SPRM1hc, bottom panel) in protein extracts prepared from male parasites (left) or female parasites (right) treated with SmAE (lanes 1), SmCB1 (lanes 2), control (lanes 3) or no (lanes 4) siRNA. The arrow indicates the mature 31kDa cathepsin B protein and the arrowhead indicates the 38kDa unprocessed, procathepsin B.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by NIH-NIAID grant AI-056273. Schistosome-infected snails were provided by the Biomedical Research Institute through NIH –NIAID Contract N01-AI-30026. We thank David Ndegwa for technical assistance and Dr. Charles Shoemaker for critically reviewing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dalton JP, Clough KA, Jones MK, Brindley PJ. Characterization of the cathepsin-like cysteine proteinases of Schistosoma mansoni. Infect Immun. 1996;64(4):1328–34. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.4.1328-1334.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tort J, Brindley PJ, Knox D, Wolfe KH, Dalton JP. Proteinases and associated genes of parasitic helminths. Adv Parasitol. 1999:43161–266. doi: 10.1016/s0065-308x(08)60243-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caffrey CR, McKerrow JH, Salter JP, Sajid M. Blood ‘n’ guts: an update on schistosome digestive peptidases. Trends Parasitol. 2004;20(5):241–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abdulla MH, Lim KC, Sajid M, McKerrow JH, Caffrey CR. Schistosomiasis Mansoni: Novel Chemotherapy Using a Cysteine Protease Inhibitor. PLoS Med. 2007;4(1):e14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gotz B, Klinkert MQ. Expression and partial characterization of a cathepsin B-like enzyme (Sm31) and a proposed ‘haemoglobinase’ (Sm32) from Schistosoma mansoni. Biochem J. 1993;290(3):801–6. doi: 10.1042/bj2900801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klinkert MQ, Felleisen R, Link G, Ruppel A, Beck E. Primary structures of Sm31/32 diagnostic proteins of Schistosoma mansoni and their identification as proteases. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1989;33(2):113–22. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(89)90025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caffrey CR, Ruppel A. Cathepsin B-like activity predominates over cathepsin L-like activity in adult Schistosoma mansoni and S. japonicum. Parasitol Res. 1997;83(6):632–5. doi: 10.1007/s004360050310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krautz-Peterson G, Radwanska M, Ndegwa D, Shoemaker CB, Skelly PJ. Optimizing gene suppression in schistosomes using RNA interference. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2007;153(2):194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skelly PJ, Shoemaker CB. Schistosoma mansoni proteases Sm31 (cathepsin B) and Sm32 (legumain) are expressed in the cecum and protonephridia of cercariae. J Parasitol. 2001;87(5):1218–21. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2001)087[1218:SMPSCB]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steiner DF, Docherty K, Carroll R. Golgi/granule processing of peptide hormone and neuropeptide precursors: a minireview. J Cell Biochem. 1984;24(2):121–30. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240240204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Docherty K, Hutton JC, Steiner DF. Cathepsin B-related proteases in the insulin secretory granule. J Biol Chem. 1984;259(10):6041–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gotz B, Felleisen R, Shaw E, Klinkert MQ. Expression of an active cathepsin B-like protein Sm31 from Schistosoma mansoni in insect cells. Trop Med Parasitol. 1992;43(4):282–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghoneim H, Klinkert MQ. Biochemical properties of purified cathepsin B from Schistosoma mansoni. Int J Parasitol. 1995;25(12):1515–9. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(95)00079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.el Meanawy MA, Aji T, Phillips NF, Davis RE, Salata RA, Malhotra I, McClain D, Aikawa M, Davis AH. Definition of the complete Schistosoma mansoni hemoglobinase mRNA sequence and gene expression in developing parasites. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1990;43(1):67–78. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1990.43.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dalton JP, Brindley PJ. Schistosome asparaginyl endopeptidase Sm32 in hemoglobin digestion. Parasitol Today. 1996;12(3):125. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(96)80676-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caffrey CR, Mathieu MA, Gaffney AM, Salter JP, Sajid M, Lucas KD, Franklin C, Bogyo M, McKerrow JH. Identification of a cDNA encoding an active asparaginyl endopeptidase of Schistosoma mansoni and its expression in Pichia pastoris. FEBS Lett. 2000;466(23):244–8. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01798-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dalton JP, Hola-Jamriska L, Brindley PJ. Asparaginyl endopeptidase activity in adult Schistosoma mansoni. Parasitol. 1995;111(5):575–80. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000077052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sajid M, McKerrow JH, Hansell E, Mathieu MA, Lucas KD, Hsieh I, Greenbaum D, Bogyo M, Salter JP, Lim KC, Franklin C, Kim JH, Caffrey CR. Functional expression and characterization of Schistosoma mansoni cathepsin B and its trans-activation by an endogenous asparaginyl endopeptidase. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2003;131(1):65–75. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(03)00194-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Correnti JM, Brindley PJ, Pearce EJ. Long-term suppression of cathepsin B levels by RNA interference retards schistosome growth. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2005;143(2):209–15. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caffrey CR, Salter JP, Lucas KD, Khiem D, Hsieh I, Lim KC, Ruppel A, McKerrow JH, Sajid M. SmCB2, a novel tegumental cathepsin B from adult Schistosoma mansoni. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2002;121(1):49–61. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(02)00022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krautz-Peterson G, Camargo S, Huggel K, Verrey F, Shoemaker CB, Skelly PJ. Amino Acid Transport in Schistosomes: Characterization of the Permease Heavy Chain SPRM1hc. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(30):21767–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703512200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delcroix M, Sajid M, Caffrey CR, Lim KC, Dvorak J, Hsieh I, Bahgat M, Dissous C, McKerrow JH. A multienzyme network functions in intestinal protein digestion by a platyhelminth parasite. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(51):39316–29. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607128200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]