Abstract

Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) is highly enriched in excitatory synapses in the central nervous system and is critically involved in synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory. However, the precise temporal and spatial regulation of CaMKII activity in living cells has not been well described, due to lack of a specific method. Here, based on our previous work, we attempted to generate an optical probe for fluorescence lifetime imaging (FLIM) of CaMKII activity by fusing the protein with donor and acceptor fluorescent proteins at its amino- and carboxyl-termini. We first optimized the combinations of fluorescent proteins by taking advantage of expansion of fluorescent proteins towards longer wavelength in fluorospectrometric assay. Then using digital frequency domain FLIM (DFD-FLIM), we demonstrated that the resultant protein can indeed detect CaMKII activation in living cells. These FLIM versions of Camui could be useful for elucidating the function of CaMKII both in vitro and in vivo.

Keywords: Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II, fluorescence resonance energy transfer, fluorescence lifetime imaging, two-photon laser scanning microscopy, fluorescent proteins

INTRODUCTION

Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) is a serine/threonine protein kinase crucial for synaptic plasticity in the central nervous system [1]. Ca2+-influx through postsynaptic NMDA receptor triggers the activation of CaMKII by a series of autophosphorylation events catalyzed by both inter- and intrasubunit reactions. This enables activated CaMKII to stay activated, even in the absence of Ca2+, until all subunits are dephosphorylated. This process has been suggested as an underlying mechanism for persistent change in synaptic efficacy, represented by long-term potentiation (LTP). The elevated CaMKII activity likely remodels the postsynaptic protein complex, which eventually leads to an insertion of new AMPA receptors on dendritic spine surfaces, and enhances the synaptic transmission [2–4]. Although this model is widely accepted, there are surprisingly few studies that confirm the constitutive activation of CaMKII specific to the potentiated synapse [5–7]. To detect this activation, we previously designed an approach to observe CaMKII activity by detecting conformational change of CaMKII associated with its activation. This was accomplished by constructing a tandem fusion of YFP, CaMKII, and CFP, the engineered sensor named Camui, and measuring its fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) [8].

Camui showed FRET in its inactive state. In the presence of ATP and calmodulin, the stimulation with Ca2+ causes a rapid (<1 min) decrease of FRET. This change arises from a conformational change due to both binding with Ca2+/calmodulin and autophosphorylation. Even after the addition of EGTA, the change in FRET persists. This persistent, Ca2+-independent change in FRET is abolished by omitting ATP or by eliminating the kinase activity (K42R) with a point mutation at the catalytic core. Therefore, a process involving autophosphorylation is contributing to the persistent change, most likely the autophosphorylation at threonine 286 (T286) on the autoinhibitory domain. In fact, a phosphoblocking mutation (T286A) blocks the persistent change in FRET, whereas a phosphomimicking mutation (T286D) is sufficient to induce change in FRET without Ca2+ stimulation. Therefore, Camui detects the activation of CaMKII by the Ca2+/calmodulin binding and the subsequent autophosphorylation.

Recent studies pointed out certain advantages of FLIM imaging over other imaging modalities to detect protein interaction or conformational change using FRET [9–12]. FLIM imaging detects FRET-induced changes in nanosecond-order fluorescence decay-time of the donor fluorescence after excitation. The decay time-constant of donor fluorescence is independent of the concentration of the probe [10], and can circumvent some of the difficulties associated with the ratiometric imaging of FRET such as change in tissue scattering or absorption. However, the CFP-YFP pair, used for many FRET probes including our original Camui, is not suitable for FLIM because of a complex fluorescence decay-time of CFP [13]. Also, CFP is not the brightest of the GFP-family proteins, which makes the overall signal dim, and the spectral bleed-through reduces the dynamic range. In fact, a probe for FLIM-based FRET imaging requires different properties compared with the ratiometric FRET imaging. 1) The fluorescent decay-time of the donor is ideally single exponential. 2) The acceptor can be dim, or better, shows no fluorescence at all.

A recent expansion of GFP-related fluorescent protein family will allow us to explore the ideal combination of fluorescent proteins for a FLIM probe. In this study, motivated by the new additions of the family towards longer wavelength [14], we first tested various red-shifted fluorescent proteins as well as a novel quencher mDarkVenus as the acceptor proteins. This allowed us to use GFP or YFP as a donor, which both have single exponential fluorescence decay-time constant and are significantly brighter than CFP. After determining the optimum pairs with a fluorospectroscopic assay in cell homogenate, we tested the applicability of one of such pair to the FLIM imaging in live cells. Consequently, we identified several promising versions of Camui that could be useful for elucidating the function of CaMKII both in vitro and in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of Camui Series

YFP (Venus variant) [15] was a gift from Drs. T. Nagai (Hokkaido University) and A. Miyawaki (RIKEN); mRFP, mOrange, and mStrawberry from Dr. Roger Tsien (UCSD); pEGFP-C1, pDsRed2-C1 and pDsRed-monomer-C1 were purchased from Clontech; TagRFP from Evrogen (Moscow, Russia). All variants of Camui were constructed from rat CaMKIIα, with donor and acceptor fluorophore proteins fused at amino- and carboxyl-termini similarly to described [8] with standard molecular biological methods. They were in a mammalian expression vector based on Clontech’s pEGFP-C1 series downstream to the CMV promoter. We describe the constructs here by “N-terminal fluorophore/C-terminal fluorophore”. See Table. 1.

Table 1.

Constructs tested in this study

| Name (N-terminus/C terminus) | Förster distance (nm) | Excitation wavelength (nm) used | Donor emission peak (nm) | Acceptor emission peak (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Venus/CFP K26R/N164H | 5.21 | 433 | 477 | 528 |

| mRFP/GFP | 5.06 | 475 | 510 | 600 |

| GFP/mRFP | 5.06 | 475 | 510 | 600 |

| mOrange/GFP | 5.55 | 475 | 510 | 587 |

| mStrawberry/GFP | 5.66 | 475 | 510 | 608 |

| TagRFP/GFP | 5.05 | 475 | 510 | 577 |

| mRFP/Venus | 5.47 | 480 | 528 | 609 |

| mOrange/Venus | 5.67 | 480 | 528 | 557 |

| mStrawberry/Venus | 6.04 | 500 | 528 | 598 |

| TagRFP/Venus | 5.87 | 500 | 528 | 580 |

| DsRed monomer/Venus | 5.14 | 490 | 528 | 585 |

| mDarkYFP/mGFP | 5.81 | 457 | 510 | N.D.b |

| mDarkVenus/mGFP | N.D.a | 457 | 510 | N.D.b |

Förster distance was calculated as described [13] for each pair of donor and acceptor. The spectra for GFP, mOrange, mStrawberry, and Venus were obtained from the laboratory webpage of Dr. Roger Tsien; TagRFP from webpage of Evrogen (www.evrogen.com); others determined in-house. Quantum yield and extinction coefficient data for GFP, mOrange, mStrawberry, Venus, TagRFP, DsRed monomer from [14]; mRFP from [17]; CFP K26R/N164H by personal communication from Drs. Tomoo Ohashi and Harold P. Erickson (the extincition coefficient, 24,000 M−1cm−1 and the quantum yield, 0.63). Those for mDarkYFP have not been determined and the values for non-monomerized version (REACh2) were used [19].

Not determined due to lack of data the extinction coefficient of mDarkVenus.

None or negligible fluorescence emission.

Fluorospectrometric Measurement of FRET

Camui variants were transfected in HEK293T cells by a liposome-mediated method (Lipofectamine 2000, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). After 1–2 days, the cells were homogenized in CaMKII assay buffer composed of 40 mM HEPES-Na (pH 8.0), 0.1 mM EGTA, 5 mM magnesium acetate, 0.01% Tween-20, 1 mM DTT, and protease inhibitor cocktail (1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride; 260 µM N-α-p-tosyl-L-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride; 10 mM benzamidine). After centrifugation, the supernatant was used for measurement. Fluorescence spectra were obtained with a spectrofluorophotometer (RF-5301PC, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). To stimulate Camui, Ca2+ (1 mM) was added in the presence of 1 µM calmodulin and 50 µM ATP at room temperature. The reaction was stopped by 1.5 mM EGTA. Fluorescence intensity was adjusted according to the volume changes. Spectroscopic parameters are in Table 1.

Expression and Imaging of GFP

The coding region for GFP (EGFP, Clontech) was PCR-amplified and subcloned into the pET-21d vector (Novagen, San Diego, CA). GFP protein was expressed in BL21(DE3) cells and then purified to homogeneity by using the Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Imaging was done using 20 µM GFP in 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4).

Expression and Imaging of Camui in HEK293T cells

HEK293T cells were transfected as above. The cells were imaged as described [8]. Digital frequency domain FLIM (DFD-FLIM) images (Fig. 3 and 4) were taken with a custom-made, photon counting two-photon microscopy system [16], by digitally heterodyning emission photons with a 79.916 MHz frequency generated from the 80 MHz laser in a field-programmable gate array (FPGA) chip (Xilinx Spartan 3E, XC3S100E, San Jose, CA). The fluorescence emission was detected with photo-multiplier tube (PMT) (R7400U-04, Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan), amplified (ACA-4-35-N 35 dB; 1.8 GHz, Becker & Hickl, Berlin, Germany) and digitized (Model 6915, Philips Scientifics, Mahwah, NJ) prior to the heterodyning. The laser repetition signal was provided by the photodiode output on the Spectra-Physics 3930 unit, amplified and digitized (Model 6930, Philips Scientifics) before arriving at the FGPA chip. Excitation wavelength was set at 910 nm. GFP emission was detected with a band-pass filter 525/50 nm. The FLIM images were processed with Globals for Images software (Laboratory for Fluorescence Dynamics, University of California, Irvine).

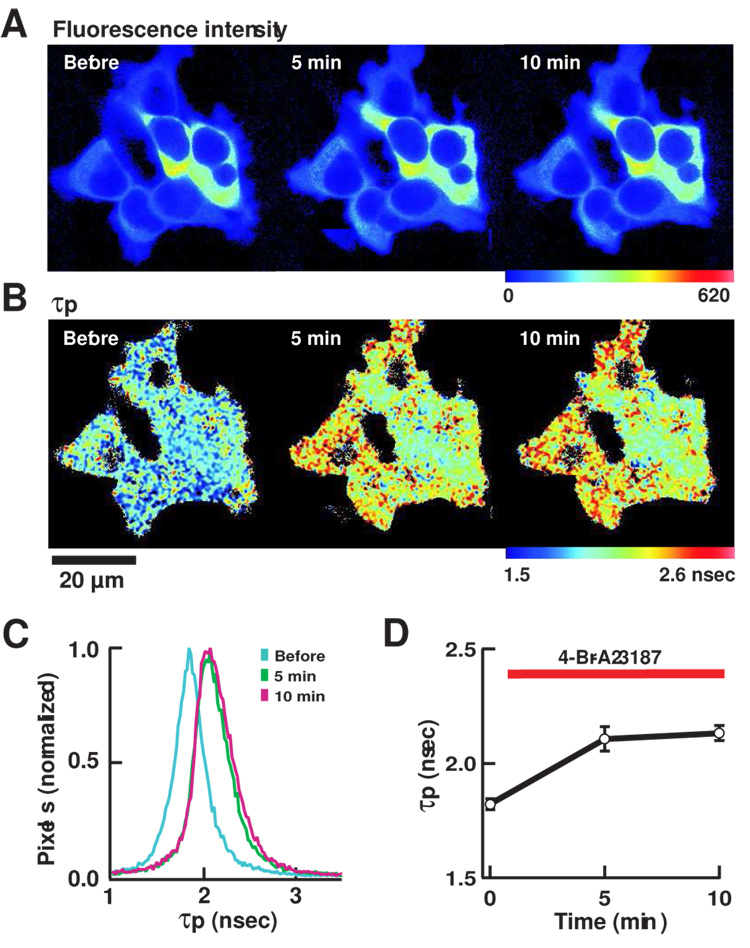

Figure 3. FLIM imaging of mRFP/GFP-Camui in HEK293T cells.

(A) Pseudocolor images of fluorescence intensity. Warmer hue corresponds to higher intensity. Time stamp indicates the time elapsed after the bath application of 4-Br-A23187. When the photon count reached a set value, the acquisition was stopped to maintain a similar standard deviation in measured fluorescence lifetime values. Therefore the brightness of image can be compared only within an image. (B) Pseudocolor image of τp. The warmer hue indicates longer τp. (C) A histogram of distribution of τp, before and after the application of 4-Br-A23187. (D) A plot of τp in 8 cells from 2 independent experiments. Results are average ± s.e.m.

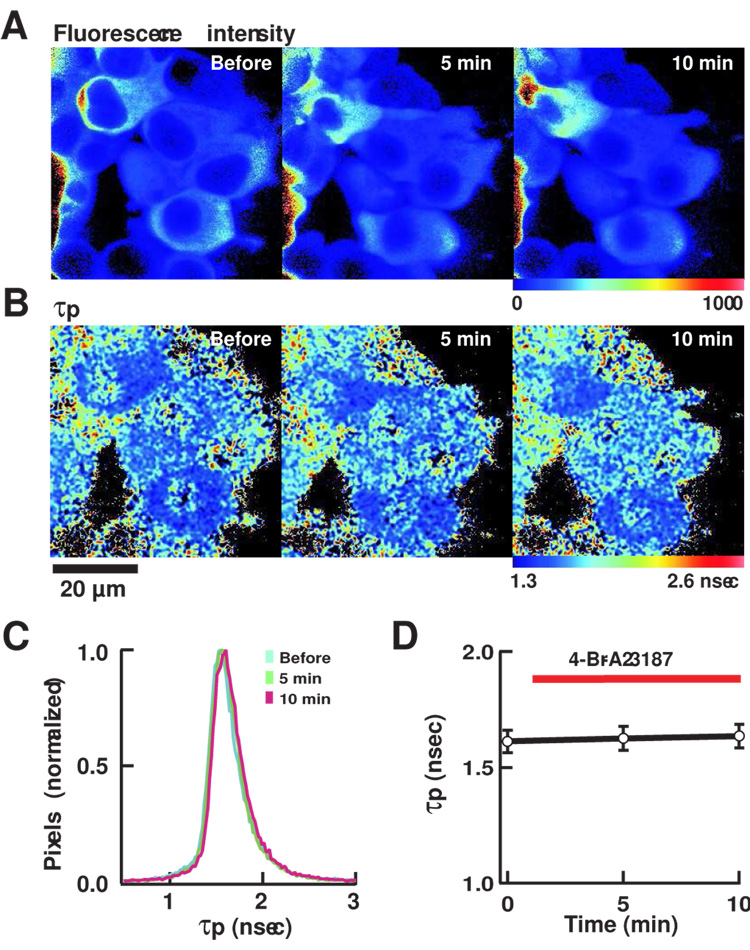

Figure 4. FLIM imaging of mRFP/GFP-Camui-T305D/T306D.

FLIM images of cells expressing mRFP/GFP-Camui with T305D/T306D mutations that render CaMKII insensitive to Ca2+/calmodulin. (A) Fluorescence intensity. (B) τp. (C) A histogram of distribution of τp. (D) A plot of τp in 6 cells shown in (A). See legend for Figure 3 for detail.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Improvement of Camui using GFP-mRFP Pair

We first used fluorospectrometry for testing constructs as it offers a quantitative comparison of FRET among multiple samples. The criteria we used are; (1) The extent of change in FRET efficiency in response to Ca2+-stimulation as measured by dequenching of donor channel. (2) The brightness of acceptor channel (darker is better).

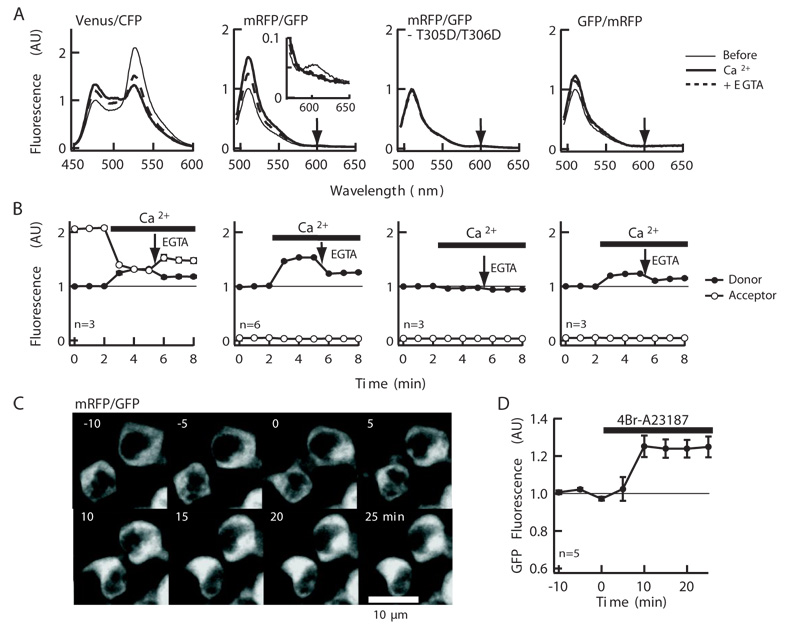

We employed a monomeric version of DsRed, monomeric red fluorescent protein (mRFP) [17] to construct mRFP/GFP- and GFP/mRFP-Camui, which is indeed reported as a fluorophore pair for FLIM imaging (Fig. 1A and B) [9, 10]. Observing transfected cells using fluorescent microscope at their optimum excitation wavelengths showed a reasonable green and red fluorescence (not shown). In the spectral analyses of the homogenate of the cells expressing these proteins upon GFP specific excitation at 475 nm, we could observe a distinct peak corresponding to GFP emission but the mRFP peak was very small, barely seen over the skew of GFP peak (Fig. 1A). Stimulation Ca2+ led to a rapid (<1 min) and stable increase in GFP peak by 53.2 ± 0.7% and eliminated the mRFP peak (Fig. 1A and B). After the addition of EGTA, the GFP peak decreased but to 25.8 ± 1.1% still above the initial level. Therefore, although mRFP peak was barely visible, FRET indeed occurred in mRFP/GFP-Camui and GFP was quenched by it. This is not surprising considering the modest extinction coefficient (44,000 M−1cm−1) and low fluorescence quantum yield (0.25) of mRFP [17]. This is, in fact, beneficial for application to FLIM imaging as it requires only the donor fluorescence and contamination with the acceptor fluorescence can distort the measured lifetime of the donor. Notably, the extent of donor dequenching in mRFP/GFP-Camui was larger than Venus/CFP-Camui under the same conditions, which was approximately 31.8 ± 2.0% by the addition of Ca2+ and 17.8 ± 1.9% after the chelation with EGTA (Fig. 1A and B). In a control construct where Ca2+/calmodulin binding site is mutated so that it does not bind with Ca2+/calmodulin complex (T305D/T306D of CaMKIIα)[8], the spectral profile was unchanged even after the addition of Ca2+/calmodulin (Fig. 1A and B). Therefore, this FRET change was associated with the activation of the CaMKII moiety of the construct through Ca2+/calmodulin binding. The reverse construct, GFP/mRFP-Camui exhibited an overall smaller response with the same manipulation, indicating that the steric arrangement of two fluorophores is important (Fig. 1A and B).

Figure 1. mRFP/GFP-Camui showed a significant dequenching upon stimulation.

(A) The emission spectra of the Venus/CFP-Camui, mRFP/GFP-Camui, mRFP/GFP-Camui with T305D/T306D mutations and GFP/mRFP-Camui made with the HEK293T cell lysate expressing each construct before, 3 min after the addition of 1 mM Ca2+, and 3 min after the addition of 1.5 mM EGTA, at the donor specific excitation. The expected positions of acceptor peaks are shown by downward arrows. A 10-fold magnification of the mRFP emission peak is shown in the inset for mRFP/GFP-Camui. (B) A plot of donor and acceptor peak intensity over time, normalized by the donor peak intensity before application of Ca2+. The response was monitored every 1 min. (C) GFP fluorescence image of HEK293T cells expressing mRFP/GFP-Camui. (D) A summary of GFP fluorescence intensity in HEK293T cells. Intensity was normalized to the average intensity prior to stimulation for each cell. The error bars are s.e.m.

We imaged HEK293T cells expressing mRFP/GFP-Camui and stimulated them with Ca2+-ionophore, 4-Br-A23187. Consistent with the observation from cell homogenates, there was an increase in GFP fluorescence by the stimulation (Fig. 1C and D). The response was slower than in cell homogenate, likely due to the time lag of the perfusing system and the drug effect. In fact, when we pre-permeabilize the cells expressing YFP/CFP-Camui with 4-Br-A23187 in Ca2+-free extracellular solution and locally puff-applied Ca2+-containing extracellular solution, the FRET started changing within 10 sec and reached maximum within 1 min (K. Takao and Y. Hayashi, unpublished).

Comparison among Spectral Variants of mRFP and GFP

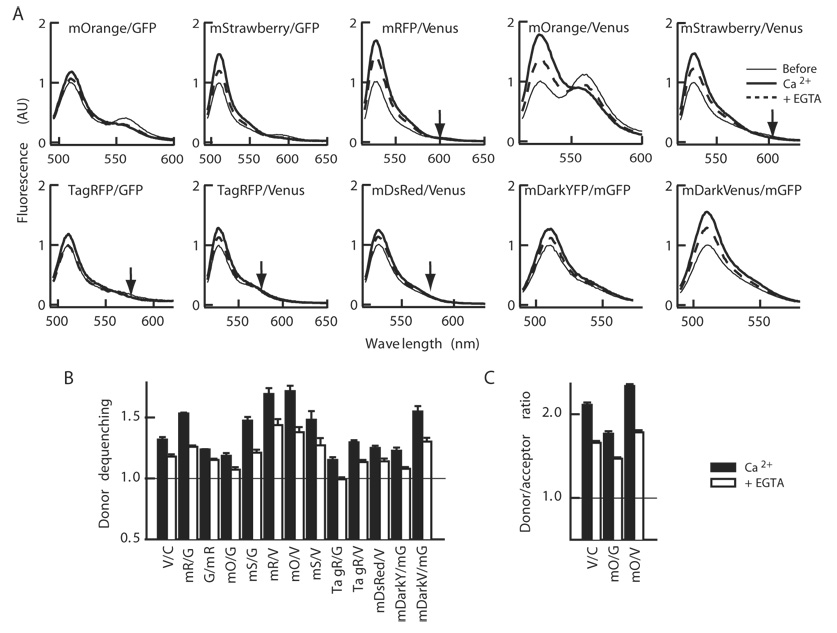

Recent expansion of the mRFP family encouraged us to explore additional members of the family [14]. We selected mOrange and mStrawberry to replace mRFP because of the better absorbance compared with the original mRFP (extinction coefficient, 71,000 and 90,000 M−1cm−1 for mOrange and mStrawberry, respectively[14]). Also, in order to improve the spectral overlap of donor emission with acceptor excitation, GFP was replaced with Venus version of YFP. We focused on the constructs with the acceptor and donor at the N- and C-termini respectively as mRFP/GFP showed better dequenching than GFP/mRFP. The junction sequence between fluorophore proteins and CaMKII were kept the same as mRFP/GFP-Camui to see the pure effects of changing the fluorophores. This yielded mOrange/GFP-, mStrawberry/GFP-, mRFP/Venus-, mOrange/Venus-, and mStrawberry/Venus-versions of Camui (Fig. 2A). The Förster distance of the pairs was calculated (Table 1).

Figure 2. Comparison of various color variants of Camui.

(A) The emission spectra of various color variants of Camui in response to Ca2+ and subsequent chelation with EGTA at donor specific excitation. Experiments were conducted similarly to Figure 1. (B and C) A summary of change in donor fluorescence intensity (B) and donor/acceptor ratio (C). Average ± s.e.m of 3–8 experiments.

Among the new mRFP family constructs, mOrange/Venus-Camui showed the best change upon stimulation with Ca2+/calmodulin; the donor fluorescence intensity was increased by 71.6 ± 4.4% and still 37.8 ± 4.2% above the baseline after chelation (Fig. 2A and B). However, the acceptor fluorescence observed may hamper the use in FLIM imaging though it may be suitable for ratiometric imaging as evidenced by a larger change in the ratio of donor and acceptor peaks (Fig. 2C). mOrange/GFP-Camui has a similar calculated Förster distance compared with mOrange/Venus-Camui (Table 1) but showed a smaller response (Fig. 2A–C).

Among the remaining probes, mRFP/Venus-Camui increased the donor peak by 69.3 ± 4.7% in response to the Ca2+ stimulation and 43.7 ± 5.0% above the baseline after the chelation of Ca2+ with EGTA (Fig. 2A and B). mStrawberry/GFP- and mStrawberry/Venus-versions also showed significant dequenching of donor which persisted after the chelation of Ca2+. Unlike mOrange, mRFP and mStrawberry peaks were negligible in these constructs. We also constructed DsRed-monomer/Venus-Camui, using DsRed-monomer (Clontech) which has been monomerized in a completely different trajectory of mutagenesis as well as TagRFP, a newly reported red fluorescent protein from sea anemone [18]. Both did not show satisfactory dequenching upon Ca2+ stimulation (Fig. 2A and B). TagRFP/GFP-Camui did not show persistent change after the addition of EGTA. We speculate this is due to the specific configuration of fluorophores in this construct or simply due to overall lower efficiency of FRET.

Application of Non-radiating YFP

As an additional effort, we employed mDarkYFP, a YFP variant with non-radiating mutations, Y145W/H148V [19], along with A206K mutation that prevents weak dimer formation [20] and mDarkVenus, a Venus variant with the same mutations, as acceptors, both with monomeric GFP (mGFP) as a donor. Among them, mDarkVenus/mGFP-Camui showed a good dequenching, 54.9 ± 4.4% above baseline upon stimulation and 30.2 ± 3.0% after chelation of Ca2+ (Fig. 2A and B) but the extent did not exceed that of mRFP- or mStrawberry-versions.

In summary, mRFP/GFP-, mStrawberry/GFP-, mRFP/Venus-, mStrawberry/Venus-, mDarkVenus/mGFP-Camui, appeared comparably promising as FLIM probes for CaMKII activity with a robust dequenching upon stimulation and barely visible acceptor fluorescence. Different versions responded differently in a way not readily predicted by the calculated Förster distance, underscoring the importance of actually testing different fluorophore combinations (Table 1, Fig. 2B). One reason for this dissociation might be the tolerance of the fluorescent protein fusing with another protein[14].

Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging of Camui Activation in HEK293T Cells

We chose the Camui with prototypical mRFP/GFP pair to perform FLIM imaging in living cells. We imaged mRFP/GFP-Camui in HEK293T cells (Fig. 3A–D). The averaged fluorescence lifetime was 1.82 ± 0.02 nsec (τp) and 2.62 ± 0.20 nsec (τm) (Fig. 3C–D), which was significantly smaller than the GFP (2.90 ± 0.44 nsec (τp) and 2.75 ± 0.23 nsec (τm)) indicating the occurrence of FRET. Upon stimulation with Ca2+-ionophore, 4-Br-A23187, the average fluorescence lifetime increased eventually to 2.13 ± 0.03 nsec (τp) and 2.83 ± 0.23 nsec (τm) after 10 min, consistent with a decrease in FRET seen in fluorospectroscopic assay (Fig. 3B–D). In order to see if this change was truly induced by Ca2+/calmodulin binding, we imaged mRFP/GFP-Camui with T305D/T306D mutations that abolish the binding with Ca2+/calmodulin. The mRFP/GFP-Camui mutant showed a much smaller fluorescence lifetime, 1.61 ± 0.05 nsec (τp) and 2.12 ± 0.03 nsec (τm) at the basal status and was unresponsive to Ca2+ stimulation (Fig. 4A–D), consistent with the idea that the change in time-constant seen in mRFP/GFP-Camui was indeed triggered by Ca2+/calmodulin.

FLIM has several advantages over ratiometric imaging for detecting FRET. It offers the ability to determine the absolute ratio of population showing FRET. Also, it does not depend on the fluorescence intensity or the acceptor channel. The latter feature makes FLIM ideal for in vivo imaging [9, 10]. In brain tissue, light is scattered significantly, depending on the depth of the tissue being imaged and the existence of local structures, such as vasculatures. Also, neuronal activity may change the scattering. If scattering affects donor and acceptor channels differently, it will give a pseudo-positive signal in the ratiometric imaging. This is no longer a concern in FLIM, however, because the scattering does not change the fluorescence lifetime. In addition, mRFP, mStrawberry, and mDarkVenus, are significantly dimmer than the donor (GFP or Venus), and therefore the emission from the acceptor is negligible (Fig. 1 and 2)[14]. This allows us to use a wider band pass filter for donor channel, thereby improving the effectiveness of photon detection, unlike ratiometric imaging that requires narrow band-pass filters to separate the two channels. Furthermore, GFP and Venus are both significantly brighter than CFP, which has been the popular donor choice for ratiometric imaging.

In addition to elucidating the physiological regulation of CaMKII in living cells, the FLIM Camui probe will allow us to identify synapses undergoing synaptic potentiation, thereby empowering us in studying the functional anatomy of local synaptic circuits. Together with recent developments of two-photon imaging techniques such as imaging in freely-moving animals and of imaging deep brain structures such as hippocampus using relay lens [21, 22], Camui will provide important information on the learning processes in unprecedented ways.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Ms. Min Deng, Mr. Kayi Lee, Drs. Ryohei Yasuda, Takeharu Nagai, Tomoo Ohashi, Harold P. Erickson, Mark Rizzo, Atsushi Miyawaki, Roger Tsien, and Kaoru Endo for valuable advices and sharing of resources, and Mr. John C. Howard and Ms. Marissa Stearns for editing. YH is supported by grants from RIKEN and NIH R01DA17310 and TH and EG from NIH PHS 5 P41 RR03155.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lisman J, Schulman H, Cline H. The molecular basis of CaMKII function in synaptic and behavioural memory. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002;3:175–190. doi: 10.1038/nrn753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shi SH, Hayashi Y, Petralia R, Zaman S, Wenthold R, Svoboda K, Malinow R. Rapid spine delivery and redistribution of AMPA receptors after synaptic NMDA receptor activation. Science. 1999;284:1811–1816. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5421.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayashi Y, Shi SH, Esteban JA, Piccini A, Poncer JC, Malinow R. Driving AMPA receptors into synapses by LTP and CaMKII: requirement for GluR1 and PDZ domain interaction. Science. 2000;287:2262–2267. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malinow R, Mainen ZF, Hayashi Y. LTP mechanisms: from silence to four-lane traffic. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2000;10:352–357. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00099-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ouyang Y, Rosenstein A, Kreiman G, Schuman EM, Kennedy MB. Tetanic stimulation leads to increased accumulation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II via dendritic protein synthesis in hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:7823–7833. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-18-07823.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fukunaga K, Muller D, Miyamoto E. Increased phosphorylation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II and its endogenous substrates in the induction of long-term potentiation. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:6119–6124. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.11.6119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ouyang Y, Kantor D, Harris KM, Schuman EM, Kennedy MB. Visualization of the distribution of autophosphorylated calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II after tetanic stimulation in the CA1 area of the hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:5416–5427. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-14-05416.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takao K, Okamoto K, Nakagawa T, Neve RL, Nagai T, Miyawaki A, Hashikawa T, Kobayashi S, Hayashi Y. Visualization of synaptic Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II activity in living neurons. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:3107–3112. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0085-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yasuda R, Harvey CD, Zhong H, Sobczyk A, van Aelst L, Svoboda K. Supersensitive Ras activation in dendrites and spines revealed by two-photon fluorescence lifetime imaging. Nat. Neurosci. 2006;9:283–291. doi: 10.1038/nn1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yasuda R. Imaging spatiotemporal dynamics of neuronal signaling using fluorescence resonance energy transfer and fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2006;16:551–561. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallrabe H, Periasamy A. Imaging protein molecules using FRET and FLIM microscopy. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2005;16:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gratton E, Breusegem S, Sutin J, Ruan Q, Barry N. Fluorescence lifetime imaging for the two-photon microscope: time-domain and frequency-domain methods. J Biomed Opt. 2003;8:381–390. doi: 10.1117/1.1586704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rizzo MA, Springer G, Segawa K, Zipfel WR, Piston DW. Optimization of pairings and detection conditions for measurement of FRET between cyan and yellow fluorescent proteins. Microsc Microanal. 2006;12:238–254. doi: 10.1017/S1431927606060235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaner NC, Steinbach PA, Tsien RY. A guide to choosing fluorescent proteins. Nat Methods. 2005;2:905–909. doi: 10.1038/nmeth819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagai T, Ibata K, Park ES, Kubota M, Mikoshiba K, Miyawaki A. A variant of yellow fluorescent protein with fast and efficient maturation for cell-biological applications. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002;20:87–90. doi: 10.1038/nbt0102-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colyer RA, Lee C, Gratton E. A novel fluorescence lifetime imaging system that optimizes photon efficiency. Microsc Res Tech. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20540. (In the press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campbell RE, Tour O, Palmer AE, Steinbach PA, Baird GS, Zacharias DA, Tsien RY. A monomeric red fluorescent protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:7877–7882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082243699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merzlyak EM, Goedhart J, Shcherbo D, Bulina ME, Shcheglov AS, Fradkov AF, Gaintzeva A, Lukyanov KA, Lukyanov S, Gadella TW, Chudakov DM. Bright monomeric red fluorescent protein with an extended fluorescence lifetime. Nat Methods. 2007;4:555–557. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ganesan S, Ameer-Beg SM, Ng TT, Vojnovic B, Wouters FS. A dark yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)-based Resonance Energy-Accepting Chromoprotein (REACh) for Förster resonance energy transfer with GFP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:4089–4094. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509922103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zacharias DA, Violin JD, Newton AC, Tsien RY. Partitioning of lipid-modified monomeric GFPs into membrane microdomains of live cells. Science. 2002;296:913–916. doi: 10.1126/science.1068539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Helmchen F, Fee MS, Tank DW, Denk W. A miniature head-mounted two-photon microscope. High-resolution brain imaging in freely moving animals. Neuron. 2001;31:903–912. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00421-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jung JC, Schnitzer MJ. Multiphoton endoscopy. Opt Lett. 2003;28:902–904. doi: 10.1364/ol.28.000902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]