Abstract

We performed studies on murine models and human volunteers to examine the immunoenhancing effects of the naturally outdoor-cultivated fruit body of Agaricus brasiliensis KA21 (i.e. Agaricus blazei). Antitumor, leukocyte-enhancing, hepatopathy-alleviating and endotoxin shock-alleviating effects were found in mice. In the human study, percentage body fat, percentage visceral fat, blood cholesterol level and blood glucose level were decreased, and natural killer cell activity was increased. Taken together, the results strongly suggest that the A. brasiliensis fruit body is useful as a health-promoting food.

Keywords: A. brasiliensis, clinical research, cold water extract, NK activity, outdoor-cultivated, safety

Alternative medicine is the general term for ‘medicine and treatment that have not been verified scientifically or applied clinically in modern Western medicine’ (1–12). The range of alternative medicine varies widely to include traditional medicine and folk remedies as well as new therapies that are not covered by health insurance. Considering the current world population, the percentage of people utilizing modern Western medicine is surprisingly low, with the World Health Organization (WHO) indicating that 65–80% of health management is by traditional medicine. ‘Mibyou’ is a recently established term that means a half-sick person having clinical laboratory data that borders healthy individuals and patients. Education of the mibyou population about eating habits is also significantly important for maintaining public health by the government.

In Japan, an increasing number of people are turning to alternative medicine mainly in the form of health foods such as amino acids, lipids, carbohydrates, plants, seaweeds, insects, bacteria, yeasts and mushrooms. Such mushrooms as Lentinula edodes, Ganoderma lucidum and Grifola frondosa are commercially available. Agaricus brasiliensis (A. blazei ss. Heinemann) is a health food that has received recent attention. A. brasiliensis has been reported to improve symptoms of lifestyle-related diseases including obesity, hypertension and diabetes, and to have anti-inflammatory, antitumor, cancer inhibitory and immuno-enhancing effects (13–18). However, many reports were either animal studies or clinical studies with few cases.

Many mushrooms, also called as macrofungi, are classified as higher-order microorganisms, Basidiomycota. To discuss the functions of Basidiomycota, it is important to compare them under the same conditions, including not only the species but also the strain, as well as methods of cultivation and processing. Basidiomycota products involve mycelia, spores and fruit bodies in each species. The fruit body and the mycelium are distributed widely in foods. To maintain the manufacturing process, the mycelium is superior to the fruit body; however, its components are known to be quite different. There are many ways to obtain the fruit body, e.g. collecting naturally grown mushrooms from hills and fields, and outdoor or indoor cultivation.

Agaricus brasiliensis KA21 used in this study is a fruit body cultivated outdoors in Brazil. Fruit bodies were air dried by a ventilator with a blowing temperature lower than 60°C to maintain their enzyme activities. We have recently examined the structure and antitumor activity of polysaccharide fractions of the fruit body and concluded significant contribution of the highly branched 1,3-β-glucan moiety on the activity. We also prepared the cold and the hot water extracts (AgCWE and AgHWE) and examined on a murine diabetic model C57Bl Ksj-db/db, and found that AgCWE showed much stronger pharmacological activity to this model. These facts strongly suggested that pharmacological action of cold water extract differ from that of hot water extract. We have also shown that the cold water extract contains enzymes such as polyphenol oxidase and peroxidase (19–25). Table 1 shows the general constituents of A. brasiliensis KA21. KA21 has high protein and fiber content. It also has high levels of vitamins B1, B2, B6, niacin, pantothenic acid, folic acid and biotin. It contains many minerals including large amounts of iron, potassium, phosphorus, magnesium, zinc and copper, and certain amounts of manganese and selenium. In addition, it contains detectable concentrations of vitamin D as it is cultivated under the sunlight.

Table 1.

Composition of A. brasiliensis KA21

| Energy | 288.00 kcal |

| Protein | 38.50 g |

| Fat | 2.60 g |

| Carbohydrate | 27.70 g |

| β-glucan | 12.4 g |

| Fiber | 20.60 g |

| Sodium | 8.40 mg |

| Calcium | 22.50 mg |

| Iron | 10.10 mg |

| Potassium | 2920.00 mg |

| Phosphorus | 952.00 mg |

| Magnesium | 96.50 mg |

| Zinc | 7.87 mg |

| Copper | 7.67 mg |

| Manganese | 0.825 mg |

| Iodine | 0 |

| Selenium | 88.00 μg |

| Arsenicum | 0 .48 ppm |

| Cadmium | 2.01 ppm |

| Plumbum | 0.13 ppm |

| Hydrargyrum | 0.18 ppm |

| Total chromium | 0 μg |

| Vitamin in A (total caronene) | 0 |

| Vitamin B (total caronene) | |

| Vitamin B1 (Thiamin) | 0.63 mg |

| Vitamin B2 (Riboflavin) | 3.04 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 0.54 mg |

| Vitamin B12 | 0 μg |

| Niacin | 33.50 mg |

| Pantothenic acid | 22.90 mg |

| Folic acid | 230.00 μg |

| Biotin | 123.00 μg |

| Total vitamin C (Total c acid) | 0 mg |

| Vitamin D | 56.7 μg |

| Vitamin E (Total tocopherol) | 0 |

| Vitamin K1 loquinone) | 0 |

| Agaritine | 15.3 ppm |

Note: In 100 g dry weight, measured by Japan Food Research laboratories.

Agaritine was measured by MASIS laboratories by HPLC method.

To successfully achieve and maintain food safety for citizens, laws related to foods have become strictly controlled. Recently, medical doctors in National Cancer Center Hospital East in Japan reported three cases of severe hepatic damage, taking A. blazei extract (26). They mentioned it is necessary to evaluate many modes of complementary and alternative medicines, including the A. blazei extract, in rigorous, scientifically designed and peer-reviewed clinical trials. Very recently we have experienced evacuation of one health food originated from A. brazei, because of inducing genotoxicity in experimental animals. Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare reported it is only the case of one product and the molecular mechanisms are under investigation. It is also simultaneously reported that other related products did not show such toxicity. Agaritine is a well known toxic metabolite of agaricaceae, such as Agaricus bisporus, and the relationship between agaritine content and the toxicity has attracted attention. In any case, function as well as safety of products originated from macrofungi, especially agaricaceae should be precisely examined as much as possible.

Thus, to safely and effectively use alternative medicine including A. brasiliensis, analysis at the molecular level by basic research and proving their effects by clinical research are important. In a human safety study, we found that long-term intake of the fruit bodies of A. brasiliensis KA21 cultivated outdoors had no adverse effects (22). In the present study, we demonstrated the immunomodulating effect of A. brasiliensis KA21 both by animal and human studies. As described earlier, the fruit body contained many enzymes even after the drying process, and cold and hot water extracts were prepared and administered orally to examine immunomodulation in mouse models. Drinking such cold water extracts of A. brasiliensis is a traditional custom in Brazil. In the clinical study, we determined the weight, body mass index (BMI), percentage body fat, percentage visceral fat and blood biochemical levels [total protein, blood glucose, cholesterol, neutral fat, glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase (GOT), glutamate pyrvic transaminase (GPT) and glutamyl transferase (γ-GTP)], and natural killer (NK) cell activity before and after administration of A. brasiliensis KA21. Analysis of the data from the viewpoint of mibyou is also included.

Methods

Agaricus brasiliensis Fruit Bodies

Strain KA21 was cultivated outdoors in Brazil, and its fruit bodies were washed and dried using hot air at 60°C or lower.

Measurement of Ingredients

All ingredients except for agaritine were measured by Japan Food Research Laboratories, Shibuya, Tokyo using the standard protocols recommended by the Resources Council, the Science and Technology Agency of Japan. The concentration of agaritine was measured by HPLC/MS/MS by MASIS Inc, Minamitusgaru, Aomori.

Preparation of Hot Water Extract (AgHWE) and Cold Water Extract (AgCWE) of A. brasiliensis

The fruit bodies of KA21 (100 g each) were ground using a domestic coffee mill, suspended in 0.1 g/ml physiological saline (Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd), and extracted in an autoclave (120°C, 20 min) or with cold water (4°C, 1 day). The supernatant after centrifugation was designated as AgHWE or AgCWE. The extracts were kept frozen at −20°C until use.

Oral Administration to Mice

AgHWE and AgCWE prepared by the earlier-described method were administered to mice orally for 2 weeks, and cell count and cell population were determined.

Murine Tumor Model

Solid form tumor: Sarcoma 180 cells (1 × 106/mouse) were subcutaneously administered to the groin of ICR mice on day 0. AgHWE or AgCWE was orally administered (p.o.) daily for 35 days. Standard β-glucan, sonifilan (SPG) was administered intraperitoneally on days 7, 9 and 11. After 35 days, the mice were sacrificed and the weight of the solid tumor was measured.

Inflammatory Cytokine Production in Primed Mice

Balb/c mice were primed with a standard β-glucan, SCG (200 μg/mouse) from Sparassis crispa on day 0, and AgHWE or AgCWE was orally administered daily for 1 week. One week later, bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 10 μg/mouse) was administered intravenously, serum was collected 90 min after the LPS administration, and serum TNF-α and IL-6 expression levels were measured with ELISA. Antibodies and standards were purchased from Pharmingen Ltd.

Concanavalin A-Induced Hepatic Injury in Mice

AgHWE or AgCWE were orally administered for several days in mice. One day after the final administration, Concanavalin A (Con A) was intravenously administered to induce liver injury. Interleukin 6 levels in sera were measured 3 h after Con A administration. GOT and GPT were measured 24 h after Con A administration.

Clinical Research in Humans

Research was performed on 31 healthy subjects who were not taking any medication prior to or at the time of the study. We explained the study to them in writing, and obtained informed consent to use the test results. The subjects were divided into three groups, group 2 and group 3 (total 20 subjects) were administered the normal dose, and group 1 (11 subjects) were administered a 3-fold higher dose (safety clinical study group) of A. brasiliensis.

Group 1. For 6 months from May 31 to November 26, 2004, the 11 subjects (mean age 43.6 ± 12.6 years, male 6, female 5) were asked to take 30 tablets/day (divided into three administrations; each tablet contained 300 mg of A. brasiliensis), which is three times the normal dose. Then, we measured and analyzed the subjective changes in their condition, liver function (GOT, GPT, γ-GTP), renal function [blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine] and nutritional status (total protein).

Group 2. For 3 months from April 12 to July 8, 2005, 12 subjects (mean age 45.3 ± 8.1 years, male 9, female 3) were asked to take the normal dose of 10 tablets/day (divided into two administrations; each tablet contained 300 mg of A. brasiliensis). Then, we measured body weight, BMI, percentage body fat, percentage visceral fat and blood biochemical levels (total protein, blood glucose, cholesterol, neutral fat, GOT, GPT and γ-GTP).

Group 3. For 3 months from May to August, 2005, 8 subjects (mean age 22.3 ± 0.5 years, male 6, female 2) were asked to take the normal dose, and immune function (NK cell count, NK cell activity) was measured. In the measurement of immune function, we divided the eight subjects into two groups in a double-blind manner, A. brasiliensis group and placebo group, administered 10 tablets/day (divided into two administrations; each tablet contained 300 mg of A. brasiliensis) for 7 days, and determined NK cell count and NK cell activity in peripheral blood. After two-month drug withdrawal, the same study was conducted with the tablets exchanged (crossover). We analyzed the cell fraction in peripheral blood and regarded mononuclear cells with CD3−CD16 + CD56+ as NK cells. Following the usual method, we measured NK cell activity by 4 h 51Cr-release assay using K562 tumor cells as targets, at an effector/target ratio (E/T) = 20 or 10 (the mixing ratio of mononuclear cells and K562 cells is 20 or 10).

Statistical Analysis

Paired t-test was used to evaluate statistical significance. P < 0.05 was considered significant in all analyses.

Results

Chemical Analysis of A. brasiliensis KA21 for Safety Assessment

Before starting animal and human experiments, the chemical composition and additives were screened. The chemical composition and nutrients are shown in Table 1. Recently, a major toxic compound of agaricaceae ‘agaritine’ has attracted attention by showing tumor-promoting activity in rats. The agaritine content of A. brasiliensis KA21 was measured and it was as low as 15.3 ppm. Heavy metals, such as lead and mercury were lower than the detection limit. Three hundred types of pesticides were measured and none was detected (data not shown).

β-glucan content of A. brasiliensis KA21 was 12.4 g 100 g−1 measured by Japan food research laboratories. We have already precisely examined the structure of polysaccharide fractions of KA21, and the major structure of β-glucan showing immunomodulating activity was determined to be β-1,6-linked glucan with highly branched β-1,3-segment (20).

Vitamin D is a well known vitamin of macrofungi and KA21 contained 56.7 μg 100 g−1 (= ca. 2250 IU 100 g−1). Same strain, cultured inside the house did not contain detectable concentration of vitamin D (data not shown). It is well known that concentration of vitamin D is strongly dependent on sunlight exposure. Vitamin D content of KA21 well reflected the culture condition of outdoor and under the sunlight.

From these data, A. brasiliensis KA21 was found to be chemically and analytically safe for animal and human studies.

Parameters and Effects on Experimental Animals

Effect on Normal Inbred Strains of Mice

For the animal experiments, AgCWE, AgHWE were prepared and examined. When AgCWE or AgHWE was administered orally at the dose of 20 mg/mouse to healthy mice (C3H/HeN) for 2 weeks, cell count in the thymus was not changed (data not shown), but that in the spleen was increased in the AgCWE group (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Cell number and population of splenocytes from AgHWE or CWE p.o. mice. AgHWE, CWE or saline (200 μl/mouse, 1 day, 1 shot), was p.o. administered to C3H/HeN mice for 14 days. The splenocytes were collected from each group of mice on day 14. Total cell number was counted with a hemocytometer (left). CD4/CD8α were measured by flow cytometory (right). The results represent the means ± S.D. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared with control by Student's t-test.

Cells were doubly stained with CD4/CD8α, αβ/γδ, or CD3/B220, and the ratios of cell populations were calculated after measurement with a flow cytometer. No notable changes were seen in the thymus (data not shown), whereas the ratio of CD4+ in the spleen was increased significantly in the AgHWE group (Fig. 1).

Antitumor Activity of Orally Administered AgCWE and AgHWE in Sarcoma 180 Transplanted Mice

We evaluated the antitumor effect of A. brasiliensis on Sarcoma 180 solid tumor, which is the standard system to measure antitumor effects in mice. Sonifilan (SPG) was used as standard material. Oral administration of AgCWE or AgHWE for 35 days led to the suppression of tumor growth (Table 2).

Table 2.

Antitumor effect of A. brasiliensis extracts on solid form of Sarcoma 180 in ICR mice

| Name | Dose (mg) | Times | Route | CR/n | Tumor weight mean/SD (g) | % Inhibition | t-test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0/12 | 8.6 ± 4.3 | 0.0 | ||||

| SPG | 0.1 | 3 | i.p. | 7/11 | 0.4 ± 1.1 | 95 | <0.001 |

| Control | 0/10 | 15.0 ± 6.5 | 0 | ||||

| AgCWE | 2 | 35 | p.o. | 0/10 | 9.6 ± 6.5 | 36 | <0.05 |

| AgHWE | 2 | 35 | p.o. | 0/10 | 7.9 ± 2.5 | 47 | <0.01 |

Note: Dose, per mouse; times, day 7, 9, 11; CR/n, Number of tumor free mice/total mouse. SPG, Standard β-glucan as positive control.

Protection against Concanavalin A-Induced Liver Injury by Orally Administered AgCWE and AgHWE in Mice

The intravenous administration of Con A, a plant lectin, triggers acute hepatopathy in mice. We administered oral AgCWE or AgHWE as pretreatment, and then assessed the effects of Con A on hepatopathy. When 200 μl of AgCWE or AgHWE was administered for 7 days as pretreatment, GOT was found to decrease significantly in the AgCWE group. A similar trend was seen in the AgHWE group. When the dose was increased to 600 μl and administration was continued for 7 days, the effect became more notable (Fig. 2). GPT was decreased in a similar manner (data not shown). Similar studies were performed using different forms of administration and several mouse lines, and all cases showed a decreasing trend. Together, the results show that A. brasiliensis KA21 protects mice from hepatic injury.

Figure 2.

Effect of AgCWE or HWE p.o. on Con A-Induced liver injury. (Left) AgHWE or CWE (200 μl/mouse) was p.o. administered to Balb/c mice for 7 days. Con A (20 mg kg−1) was iv administered on day 7 and the sera were prepared 24 h later from each group of mice. Results are expressed as the mean ± SD *P < 0.05 compared with control by Student's t-test. (N = 7). (right) AgHWE or CWE (600 μl/mouse) was p.o. administered to Balb/c mice for 7 days. Con A (20 mg kg−1) was iv administered on day 7 and the sera were prepared 24 h later from each group of mice. Results are expressed as the mean ± SD ***P < 0.001 compared with control by Student's t-test. (N = 3).

Protection of Multiple Organ Failure Induced by Lipopolysaccharide by Oral Administration of A. brasiliensis KA21

Next, we investigated cytokine production induced by the administration of bacterial endotoxin, LPS, an agent that induces multiple organ failure in severe infections, to determine the hepatocellular protective effect of AgCWE and AgHWE. The levels of TNF-α and IL-6 generated by LPS administration were decreased in both groups (Fig. 3), indicating that A. brasiliensis controls the level of cytokine production to protect organs.

Figure 3.

Effect of oral A. brasiliensis on LPS-induced cytokine production. β-Glucan (SCG, 200 μg/mouse) was i.p. administered to Balb/c mice on day 0. AgHWE or CWE was p.o. administered to these mice for 7 days. LPS (10 μg/mouse) was iv administered as a triggering reagent on day 7 and the sera were prepared 1.5 h later from each group of mice. IL-6 and TNF-α was measured by ELISA. Results are expressed as the mean ± SD *P < 0.05 compared with control by Student's t-test. (left) TNF-α, (right) IL-6.

Clinical Research

Safety of A. brasiliensis

Before determining the safety of A. brasiliensis KA21, a normal dose was administered for 3 months to 13 subjects as a preliminary experiment and measured changes of general clinical parameters. Mean body weight (71.2 → 70.9 kg), size of waist (85.4 → 83.5 cm), percentage body fat (34.4–33.0%) and BMI (27.8–27.6) did not show any clinical sign of illness by taking it. Thus to precisely determine the safety of A. brasiliensis KA21, a dose of three times higher than the normal dose was administered for 6 months to 11 subjects (group 1, see ‘Methods’), and subjective changes in conditions, liver function, renal function and nutritional conditions were measured and analyzed. After measuring the biochemical parameters, we confirmed no statistically significant difference before and after administration, and no side effects caused by long-term administration (Table 3).

Table 3.

Safety of A. brasiliensis KA21 in human volunteers

| Biochemical parameters | Before (mean ± SD) | After (mean ± SD) | Statistics (P-value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total protein (g dl−1) | 7.50 ± 0.16 | 7.41 ± 0.25 | 0.31 |

| BUN (mg dl−1) | 15.81 ± 5.93 | 13.45 ± 2.25 | 0.12 |

| Creatinine (mg dl−1) | 0.92 ± 0.21 | 0.90 ± 0.20 | 0.19 |

| GOT (μ l−1) | 18.8 ± 4.75 | 19.8 ± 4.40 | 0.10 |

| GPT (μ l−1) | 15.7 ± 6.90 | 16.3 ± 4.90 | 0.52 |

| γ-GTP (μ l−1) | 35.4 ± 29.6GTP | 35.9 ± 30.1 | 0.89 |

(N = 11).

Effect of A. brasiliensis on Biochemical Parameters related to Adiposis and Diabetes

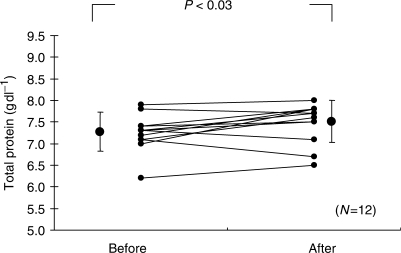

In order to evaluate the effect of A. brasiliensis KA21 on lifestyle-related diseases, the normal dose was administered to 12 subjects (group 2, see ‘Methods’) for 3 months and comparison of clinical biochemical data was made. The results are as follows: (i) Significant decreases were seen in body weight and BMI (P < 0.01 each) after administration (Figs 4 and 5). (ii) Significant decreases were observed in percentage body fat (P < 0.01) and percentage visceral fat (P < 0.01) after administration (Figs 6 and 7). (iii) Significant increase was found in total protein level (P < 0.03) after administration (Fig. 8). (iv) Significant reduction was seen in blood glucose level (P < 0.02) after administration (Fig. 9).

Figure 4.

Effect of A. brasiliensis on body weight. Experimental protocol was shown in ‘Methods’.

Figure 5.

Effect of A. brasiliensis on BMI. Experimental protocol was shown in ‘Methods’.

Figure 6.

Effect of A. brasiliensis on percentage body fat. Experimental protocol was shown in ‘Methods’.

Figure 7.

Effect of A. brasiliensis on percentage visceral fat. Experimental protocol was shown in ‘Methods’.

Figure 8.

Effect of A. brasiliensis on total protein level. Experimental protocol was shown in ‘Methods’.

Figure 9.

Effect of A. brasiliensis on blood glucose level. Experimental protocol was shown in ‘Methods’.

In order to analyze the data more precisely, the subjects were divided according to total cholesterol level into a normal value group (T-CHO < 200 mg/dl) and a mibyou (slightly sick) value group (T-CHO ≥ 200 mg/dl) for comparison. No change was observed in the T-CHO < 200 mg/dl group before and after administration, whereas a decrease was seen in the T-CHO ≥ 200 mg/dl group after administration (Fig. 10).

Figure 10.

Effect of A. brasiliensis on blood cholesterol level from the viewpoint of Mibyou. Experimental protocol was shown in ‘Methods’.

The subjects were divided according to blood neutral fat level into a normal value group (TG < 120 mg/dl) and a mibyou value group (TG ≥ 120 mg/dl) for comparison. No change was observed in the former, whereas a decrease was observed in the latter after administration (Fig. 11).

Figure 11.

Effect of A. brasiliensis on neutral fat level from the viewpoint of Mibyou. Experimental protocol was shown in ‘Methods’.

Improvement of Liver Function by A. brasiliensis

To determine liver function, we compared GOT, GPT and γ-GTP values of the earlier mentioned subjects shown in the previous section. When comparison was made among all 12 subjects, no differences were seen before and after administration (Fig. 12). By contrast, after the subjects were divided into normal and mibyou according to GOT level, the average value of GOT in the normal value group (GOT < 25 IU l−1) was found to increase slightly after administration, whereas that in the mibyou value group (GOT ≥ 25 IU l−1) was found to decrease after administration, although the difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 13). The average value of GPT was increased in the normal value group (GPT < 25 IUl−1) after administration, whereas that in the mibyou value group (GPT ≥ 25 IUl−1) was decreased slightly after administration, the difference being not statistically significant (Fig. 14). The average value of γ-GTP was decreased slightly in the normal value group (γ-GTP < 30 IU l−1) after administration, whereas that in the mibyou value group (γ-GTP ≥ 30 IU l−1) was almost unchanged (Fig. 15).

Figure 12.

Effect of A. brasiliensis on liver function. Experimental protocol was shown in ‘Methods’.

Figure 13.

Effect of A. brasiliensis on liver function (GOT Value) from the viewpoint of mibyou. Experimental protocol was shown in ‘Methods’.

Figure 14.

Effect of A. brasiliensis on liver function (GPT Value) from the viewpoint of mibyou. Experimental protocol was shown in ‘Methods’.

Figure 15.

Effect of A. brasiliensis on liver function (γ-GTP Value) from the viewpoint of mibyou. Experimental protocol was shown in ‘Methods’.

Taken together, we determined that both lipid and blood glucose levels showed a decreasing trend for lifestyle-related diseases. In addition, an improvement in liver function was noted.

Modulation of Natural Killer Cell by A. brasiliensis

In order to evaluate the effect of A. brasiliensis KA21 on immune function, NK cell number and function were examined by eight subjects in a double-blinded experimental protocol shown in ‘Methods’ (group 3, see ‘Methods’). The normal dose or placebo was administered to eight subjects for 7 days and NK cell number and activity in peripheral blood was compared as follows.

Effect of A. brasiliensis on NK Cell Count

Comparison of NK cell count before and after administration, and comparison between the A. brasiliensis group and placebo group were made, and no statistically significant differences were observed (Fig. 16).

Figure 16.

Comparison of NK cell count between groups before and after administration of A. brasiliensis. Experimental protocol was shown in ‘Methods’.

Augmentation of NK Cell Activity by A. brasiliensis KA21

Before administration, no significant differences were observed between A. brasiliensis group and placebo group (Fig. 17 left). After administration, there were significant differences between the two groups, with P < 0.01 for the E/T = 20% group and P < 0.001 for the E/T = 10% group (Fig. 17 right). Figs 18 and 19 show individual changes in NK cell activity after administration of A. brasiliensis (Fig. 18) and placebo (Fig. 19) groups. NK cell activity was increased significantly in A. brasiliensis groups, with P < 0.001 for the E/T = 20% group and P < 0.001 for the E/T = 10% group. Meanwhile, NK cell activity was not increased significantly in the placebo group after administration.

Figure 17.

Effect of A. brasiliensis on NK cell activity. (Comparison between A. blazei group and placebo group). Experimental protocol was shown in ‘Methods’.

Figure 18.

Comparison of NK cell activity before and after administration of A. brasiliensis. Experimental protocol was shown in ‘Methods’.

Figure 19.

Comparison of NK cell activity before and after administration of placebo. Experimental protocol was shown in ‘Methods’.

Discussion

Japan is rapidly becoming a super-aging society, and such issues as decreased workforce, consumption and tax revenues, and increased international competition among neighboring Asian nations are emerging. As a dramatic increase in the number of elderly patients is inevitable, the social security system is expected to become financially strained, and patient and consumer awareness of their rights will be enhanced because of the increased financial burden levied on them. Whereas genetic disposition is said to be involved in the development of lifestyle-related conditions and diseases, such as diabetes, hyperlipidemia and cancer, several other factors also determine their development; therefore, lifestyle is closely related to the development of such conditions and diseases. On the other hand, there is a need to reduce the significantly elevated medical expenses in the future. There are discussions as to whether we should pay medical expenses to aid people who do not practice a healthy lifestyle. The number of people who are not sick yet not healthy, that is, ‘in poor health’ or ‘mibyou’, is increasing at an accelerated pace (27,28). It is difficult to maintain regular eating habits in stress-laden daily life. Improvement of diet by consuming functional foods seems to contribute to the health improvement of people with poor health, as well as to the prevention of the development of lifestyle-related diseases.

There are many functional foods in Japan and they are expensive for customers, thus accurate information is needed to select the best food for each customer. All the parameters of safety, cost performance, evidence of function, as well as taste are important to disclose.

Mushrooms have been a part of oriental medicine for hundreds of years as being beneficial for health. Most traditional knowledge about the medicinal properties of mushrooms comes from the Far East, Japan, China, Korea and Russia. The most striking evidence is that lentinan from L. edodes, sonifilan from Schizophyllum commune and krestin from Coriorus versicolor have been approved for anticancer drugs mediated by immune stimulation. A great many mushroom products are on the market as health promoting foods, and basic and clinical researches of these products have been performed continuously (29–41).

Currently, there are 80 000 known fungal species in the world. It is surmised that 1 500 000 species exist, including undiscovered species. These fungi are classified by kingdom, phylum/division, class, genus and species. Many fungi are classified into Basidiomycota or Ascomycota, whereas others are also classified into the kingdom Protozoa or kingdom Chromista. Fungi include mushrooms, molds and yeasts, which have significantly different appearance and sizes. As mushrooms are too large to be considered microorganisms, they are referred to as macrofungi. Lichens of which two or more microorganisms live in a symbiotic relationship are also included. Fungi exhibit both the sexual form (for example, morphology of mushroom) and the asexual form for regeneration (for example, morphology of mycelium) and either form is used depending on surrounding environmental changes; however, the existence of both forms (holomorph) is not known for all fungi. Their nomenclature is also characteristic. The background of the discovery of a fungus is reflected in its name and different names may be given depending on whether the fungus exhibits the sexual form (teleomorph) or the asexual form (anamorph) of regeneration. Fungi, particularly mushrooms, are ‘cultivated’ and distributed products, and detailed analysis of their components has been performed. In the Standard Tables of Food Composition in Japan (Fifth Edition), 36 foods are classified as ‘mushrooms’. The representative nutritional composition of mushrooms includes fiber, glucose and sugar alcohols, organic acids, fatty acids, inorganic substances, vitamins, free amino acids, bitter and pungent components, flavor components, enzymes, biophylactic substances, pharmacologically active substances and toxic components. Moreover, molds and yeasts are related to some fermented foods. A variety of foods including sake (rice wine), miso (bean paste), soy sauce, cheese and katsuobushi (dried bonito) are manufactured with the help of eukaryotic microorganisms. Fungus produces many secondary metabolites that are used as drugs or raw material for drugs, an example of which is penicillin.

As regards edible mushrooms, some are consumed raw, and cultivated hypha and culture broth are distributed as supplements after processing. Although they are from the same fungus, there is no proof that they contain the same components as the cultivated fruit bodies. In the early 1980s, we performed animal studies to compare the macromolecular components of G. frondosa fruit bodies, mycelia and fermented products. That the quantities and quality of components contained in each extract differed considerably was also reflected in the activity (29–32). Grifola frondosa has been well studied in Japan and in other countries. Interestingly, the major active component differs depending on the study group (33–37). Comparing mushrooms and mycelia at the product level, it was found that live fungus differs from dried products. From the viewpoint of stable supply, the dried product is desirable, but its components change according to the drying method. It is likely that the components differ if the ‘fungal strain’ differs. Thus, one type of mushroom may vary greatly when processed as food or other products. When we want to discuss or evaluate components and pharmacologic action, we need to conduct comparisons under detailed conditions, especially if we perform animal experiments.

Agaritine (N-[γ-L-(+)-glutamyl]-4-hydroxymethylphenylhydrazine) was identified in fruit bodies of cultivated mushrooms belonging to the genus Agaricus, including commerce A. bisporus and closely related species (42–46). 4-(hydroxymethyl) benzenediazonium ion that had mutagenicity is believed to be formed when agaritine is metabolized. Agaritine is most prevalent, usually occurring in quantities between 200 and 400 μg g−1 as fresh weight, 1000–2500 μg g−1 as dry weight in cultivated mushroom. Recently, agaritine in A. brasiliensis (A. blazei) sample and products was measured. These samples contained 112–1791 μg g−1 of agaritine as dry weight (47). In the present study, we have detected only low concentrations of agaritine (15.3 ppm; 15.3 μg g−1) in the preparation made of A. brasiliensis KA21. This value was <1/100 of the quantity of average values of A. bisporus. Agaritine content is known to be significantly varied depending on processing. Household processing (e.g. boiling, frying, microwave heating or drying) will reduce the agaritine content in A. bisporus by up to 50% or even more (48). Also, agaritine has recently been shown to be degraded oxygen dependent in water (42,43). There have been long discussing the toxicity and carcinogenicity of agaritine (44,45). However, the conclusion is still controversial. Toth and co-workers (46,49–51) undertook the work to assess the possible carcinogenic activity of the phenylhydrazines and related compounds in A. bisporus. Their studies indicated that most of phenylhydrazine and related compounds in the mushroom are carcinogenic in Swiss albino mice. The only compound that was tested negative was agaritine, a finding that significantly muddled the interpretation of the carcinogenicity data. Also, these studies were the conservative risk model. In the absence of epidemiological data, no evaluation of carcinogenicity of agaritine to humans could be made.

We have analyzed A. brasiliensis KA21 from various aspects and reported the β-glucan, the enzymes of polyphenol oxidase, peroxidase and β-1,3-Glucanase. β-glucan content of A. brasiliensis KA21 was 12.4 g 100 g−1 measured by Japan food research laboratories. We have already precisely examined the structure of polysaccharide fractions of KA21, and the major structure of β-glucan showing immunomodulating activity was determined to be β-1,6-linked glucan with highly branched β-1,3-segment (20). During that study we have prepared hot water extract, cold alkaline extract, and hot alkaline extracts and analyzed polysaccharide structure of all these fractions. Of much interest, all the fraction showed quite similar structural features that major linkage is β-1,6-linked glucan. From these data, major polysaccharide component in A. brasiliensis is β-1,6-linked glucan, and it is consistent with the previous study. However, we have mentioned that antitumor activity needs β-1,3-linkages in addition to β-1,6-linkage based on the results of the limited chemical degradation study. However, this conclusion is still temporal and structural activity relations needed human studies.

This study showed that the fungus is rich in vitamins; as it is cultured outdoors, it contains detectable concentrations of vitamin D. Vitamin D is a well-known vitamin of macrofungi and KA21 contained 56.7 μg 100 g−1 dry weight. In the parallel experiments, vitamin D was contained lower than the detection limit (0.7 μg 100 g−1) in the mycelium of this fungi cultured in the liquid medium and the fruit body of A. blazei imported from China. Much differences of vitamin D in these products well reflected the culture condition of outdoors and under the sunlight. Relationship between vitamin D content and sunlight exposure has been demonstrated in various macrofungi (52). Based on the definition in the manual of Health Food Regulation in Japan, the food containing more than 1.5 μg 100 g−1 (= 60 IU 100 g−1) of vitamin D is defined as the food containing high vitamin D content. Considering the rule, KA21 is the food containing high concentration of vitamin D. Micronutrients such as vitamins and minerals promote the metabolism of waste products, carbohydrates and lipids via cellular activation, and improved insulin resistance by decreasing blood glucose. Fiber and unsaturated fatty acids decrease blood pressure and promote decholesterolization. KA21 also contained other micronutrients, thus it is good for health for variety of reasons.

Meanwhile, in an analysis of the active components in bupleurum root, a crude drug, we found that polyphenols polymerized by enzymes have a strong immunoenhancing effect (53–55). A. brasiliensis also has a number of enzymes related to the polymerization of polyphenols (23,24). Polyphenols polymerized by these enzymes may be active components in this fungus. In our clinical research, decreases in body weight, BMI, percentage body fat, percentage visceral fat and blood glucose level were noted and a tendency to decrease blood cholesterol level, blood neutral fat level, GOT, GPT and γ-GTP was observed in the mibyou value group. On the basis of the earlier results, among the components of this fungus, all the polysaccharides, enzymes, vitamins and minerals may be involved in the normalization of biochemical test results.

This study measured immune function in mice. When we compared the number and population of immunocompetent cells after administration of AgCWE or AgHWE to healthy mice orally for 2 weeks, it was found that the percentage of spleen CD4+T cells was increased in the AgHWE group and the number of spleen cells was increased in the AgCWE group. Furthermore, both AgCWE and AgHWE showed antitumor effects and AgCWE prevented Con A-induced hepatopathy and suppressed cytokine production induced by LPS. CD4+T cells are divided into type 1 helper T cells (Th1) and type 2 helper T cells (Th2) based on T-cell antigen stimulation, and Th1 is considered to be a more important contributor to the antitumor effect. Th1 is thought to infiltrate local sites well, demonstrate strong cytotoxicity and cytokine production ability, and induce complete tumor regression by locally inducing CTL, which has the ability to produce IFN-γ (56–58). It is likely that the antitumor effect of A. brasiliensis is closely related to the increase in CD4+T cell count. As changes in immunocytes were demonstrated by the oral administration of A. brasiliensis in healthy mice, it is expected that the daily intake of A. brasiliensis may have preventive effects on immunoregulation failure.

Agaricus brasiliensis suppressed organ dysfunction accompanied by blood with excessively high cytokine levels, which is related to multiple organ failure. It is desirable that cytokines be produced at certain levels as needed. In these models, such as LPS-elicited cytokine production, A. brasiliensis controlled excessive cytokine production (Fig. 3). A. brasiliensis can not only promote but also control immunity, which is considered a desirable effect.

Among the effects of A. brasiliensis on immune function, we examined changes in the ratio of NK cells to peripheral mononuclear cells and NK cell activity in humans. Both the A. brasiliensis group and the placebo group showed no significant changes in the ratio and number of NK cells to peripheral mononuclear cells after 1-week administration. On the other hand, comparing the A. brasiliensis and placebo groups, NK cell activity was significantly enhanced by the administration of A. brasiliensis. When individual cases were examined, almost all cases showed increasing NK cell activity with the administration of A. brasiliensis, although there were differences in the degree of increase (Fig. 18).

The measurement of NK cell activity has been most widely used in both animal and human experiments, because NK cells play a critical role in natural immunology, and measurement of cytotoxicity is reliable for evaluation with good reproducibility (5). The immune function is affected by NK cells as well as various lymphocyte and humoral factors including antibodies, complement and cytokines. There have been several publications demonstrating products of macrofungi enhanced NK activity (59–63).

The effect of A. brasiliensis on the degree of NK cell activity enhancement varied significantly among individuals. It was recently clarified that effectiveness as well as the appearance of side effects with each medication were significantly different in each individual. This is explained partly by polymorphism and the linkage of CYP-related genes, a drug-metabolizing enzyme group (64,65). On the other hand, many causative genes have been discovered in immunity-related diseases, some of which are polymorphic. It is possible that polymorphism may be related to individual differences observed in the effects of A. brasiliensis. Research into receptors for mushroom components is not extensive. Dectin-1 was recently determined to be the receptor for cell wall β-glucan, a major component of mushrooms (66–68). The relationship between polymorphism of the receptor for pathogens and disease has been elucidated (69,70). The effects of A. brasiliensis and receptor gene polymorphism may be related. Further analysis is necessary in the future.

Through basic and clinical research, we confirmed that A. brasiliensis can help to improve symptoms of lifestyle-related diseases because of its anti-inflammatory, antitumor and immunoenhancing effects, and that A. brasiliensis is a useful health food to treat mibyou (primary prevention).

Very recently we have experienced recall of one health food originated from A. brazei, because of inducing genotoxicity in experimental animals. Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare reported it is only the case of one product and the molecular mechanisms are under investigation. Based on the clinical examination shown in this study, KA21 is very safe for human health. Any adverse effect could not be detected in our study. We have also stated that content as well as pharmacological action is significantly influenced by culture conditions even in the same fungi, such as vitamin D content. In addition, proteins may be decomposed during processing. Much restricted regulation for each of the health foods might be needed for increasing human health. In any case, agaricaceae contained many species for functional foods, thus, much study should be needed continuously. This study helped to understand the mushrooms of agaricaceae are very safe and useful for human health.

Conclusion

In basic research using a mouse model, we determined that A. brasiliensis has antitumor, anti-inflammatory and hepatocellular protective effects. It was suggested that the increase in the number of helper T cells and the enhancement of NK cell activity are related to these effects.

In clinical research on human volunteers, we found that A. brasiliensis decreased body weight, BMI, percentage body fat, percentage visceral fat and blood glucose level significantly, and reduced obesity. It also decreased blood cholesterol level and neutral fat level, normalized liver function and activated the immune function in mibyou patients (people with poor health).

References

- 1.Kidd PM. The use of mushroom glucans and proteoglycans in cancer treatment. Altern Med Rev. 2000;5:4–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mayell M. Maitake extracts and their therapeutic potential. Altern Med Rev. 2001;6:48–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ventura C. CAM and cell fate targeting: molecular and energetic insights into cell growth and differentiation. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2005;2:277–83. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper EL. Bioprospecting: a CAM Frontier. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2005;2:1–3. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takeda K, Okumura K. CAM and NK cells. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2004;1:17–27. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shimazawa M, Chikamatsu S, Morimoto N, Mishima S, Nagai H, Hara H. Neuroprotection by Brazilian green propolis against in vitro and in vivo ischemic neuronal damage. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2005;2:201–7. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper EL. CAM. eCAM, bioprospecting: the 21st century pyramid. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2005;2:125–7. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindequist U, Timo H, Niedermeyer J, Jülich WD. The pharmacological potential of mushrooms. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2005;2:285–99. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Terasawa K. Evidence-based reconstruction of kampo medicine: Part I—Is kampo CAM? Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2004;1:11–16. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaminogawa S, Nanno M. Modulation of immune functions by foods. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2004;1:241–50. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atsumi K. is alternative medicine really effective? Alternative Medicine. 2000 (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atsumi K. Recommendations of Alternative Medicine. Japan Medical Planning. 2000 (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huan SJ, Mau JL. Antioxidant properties of methanolic extracts from Agaricus blazei with various doses of γ-irradiation. Food Sci Technol. 2006;39:707–16. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bellini MF, Angeli JPF, Matuo R, Terezan AP, Ribeiro LR, Mantovani MS. Antigenotoxicity of Agaricus blazei mushroom organic and aqueous extracts in chromosomal aberration and cytokinesis block micronucleus assays in CHO-k1 and HTC cells. Toxicol in Vitro. 2006;20:355–60. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhong M, Tai A, Yamamoto I. In vitro augmentation of natural killer activity and interferon-γ production in murine spleen cells with agaricus blazei fruiting body fractions. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2005;69:2466–9. doi: 10.1271/bbb.69.2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ellertsen LK, Hetland G, Johnson E, Grinde B. Effect of a medicinal extract from Agaricus blazei Murill on gene expression in a human monocyte cell line as examined by microarrays and immuno assays. Int Immunopharmacol. 2005;6:133–43. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kobayashi H, Yoshida R, Kanada Y, Fukuda Y, Yagyu T, Inagaki K, et al. Suppressing effects of daily oral supplementation of beta-glucan extracted from Agaricus blazei Murill on spontaneous and peritoneal disseminated metastasis in mouse model. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2005;131:527–38. doi: 10.1007/s00432-005-0672-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ker YB, Chen KC, Chyau CC, Chen CC, Guo JH, Hsieh CL, et al. Antioxidant capability of polysaccharides fractionated from submerge-cultured Agaricus blazei mycelia. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:7052–8. doi: 10.1021/jf0510034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohno N, Furukawa M, Miura NN, Adachi Y, Motoi M, Yadomae T. Antitumor beta-glucan from the cultured fruit body of Agaricus blazei. Biol Pharm Bulletin. 2001;24:820–8. doi: 10.1248/bpb.24.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohno N, Akanuma AM, Miura NN, Adachi Y, Motoi M. (1-3)-beta-glucan in the fruit bodoes of Agaricus blazei. Pharm Pharmacol Lett. 2001;11:87–90. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Motoi M, Ishibashi K, Mizukami O, Miura NN, Adachi Y, Ohno N. Anti beta-glucan antibody in cancer patients (preliminary report) Int J Med Mushrooms. 2004;6:41–48. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Y, Fukuwatari Y, Okumura K, Takeda K, Ohno N, Mori K, et al. Basic and clinical research on immunoregulatory activity of Agaricus blazei. Toho Igaku. 2004;20:29–36. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akanuma AM, Yamagishi A, Motoi M, Ohno N. Cloning and characterization of polyphenoloxidase DNA from Agaricus brasiliensis S. Wasser et al. (Agaricomycetideae) Int J Med Mushrooms. 2006;8:67–76. doi: 10.1615/intjmedmushr.v13.i1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hashimoto S, Akanuma AM, Motoi M, Imai N, Rodrignes CA, et al. Effect of culture conditions on chemical composition and biological activities of Agaricus braziliensis. Int J Med Mushrooms. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Furukawa M, Miura NN, Adachi Y, Motoi M, Ohno N. Effect of Agaricus brasiliensis on Murine Diabetic Model C57Bl/Ksj-db/db. Int J Med Mushrooms. 2006;8:115–28. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mukai H, Watanabe T, Ando M, Katsumata N. An alternative medicine, Agaricus blazei, may have induced severe hepatic dysfunction in cancer patients. J Clin oncology. 2006;36:808–10. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyl108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christine KC, Mark AR, Jay Olshansky S. The price of success: health care in an aging society. Health aff. 2002;21:87–99. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.11.2.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaneko H, Nakanishi K. Proof of the mysterious efficacy of ginseng: basic and clinical trials: clinical effects of medical Ginseng, Korean red Ginseng: specifically, its anti-stress action for prevention of disease. J Pharmacol Sci. 2004;95:158–62. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fmj04001x5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iino K, Ohno N, Suzuki I, Sato K, Oikawa S, Yadomae T. Structure-function relationship of antitumor beta-1,3-glucan obtained from matted mycelium of cultured Grifola frondosa. Chem Pharm Bull. 1985;33:4950–6. doi: 10.1248/cpb.33.4950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohno N, Adachi Y, Suzuki I, Oikawa S, Sato K, Ohsawa M, et al. Antitumor activity of a beta-1,3-glucan obtained from liquid cultured mycelium of Grifola frondosa. J Pharmacobiodyn. 1986;9:861–4. doi: 10.1248/bpb1978.9.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takeyama T, Suzuki I, Ohno N, Oikawa S, Sato K, Ohsawa M, et al. Host-mediated antitumor effect of grifolan NMF-5N, a polysaccharide obtained from Grifola frondosa. J Pharmacobiodyn. 1987;10:644–51. doi: 10.1248/bpb1978.10.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suzuki I, Takeyama T, Ohno N, Oikawa S, Sato K, Suzuki Y, et al. Antitumor effect of polysaccharide grifolan NMF-5N on syngeneic tumor in mice. J Pharmacobiodyn. 1987;10:72–7. doi: 10.1248/bpb1978.10.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kodama N, Asakawa A, Inui A, Masuda Y, Nanba H. Enhancement of cytotoxicity of NK cells by D-Fraction, a polysaccharide from Grifola frondosa. Oncol Rep. 2005; 13:497–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kodama N, Komuta K, Nanba H. Effect of maitake (Grifola frondosa) D-Fraction on the activation of NK cells in cancer patients. J Med Food. 2003;6:371–7. doi: 10.1089/109662003772519949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harada N, Kodama N, Nanba H. Relationship between dendritic cells and the D-fraction-induced Th-1 dominant response in BALB/c tumor-bearing mice. Cancer Lett. 2003;192:181–7. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00716-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kodama N, Komuta K, Nanba H. Can maitake MD-fraction aid cancer patients? Altern Med Rev. 2002;7:236–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Inoue A, Kodama N, Nanba H. Effect of maitake (Grifola frondosa) D-fraction on the control of the T lymph node Th-1/Th-2 proportion. Biol Pharm Bull. 2002;25:536–40. doi: 10.1248/bpb.25.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Masaki K, Hirotake K. Delayed cell cycle progression and apoptosis induced by hemicellulase-treated Agaricus blazei. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2006 doi: 10.1093/ecam/nel059. in press, available on-line. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kasai HL, He M, Kawamura M, Yang PT, Deng XW, Munkanta M, et al. IL-12 production induced by Agaricus blazei fraction H (ABH) involves toll-like receptor (TLR) Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2004;1:259–67. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Inagaki N, Shibata T, Itoh T, Suzuki T, Tanaka H, Nakamura T, et al. Inhibition of IgE-dependent mouse triphasic cutaneous reaction by a boiling water fraction separated from mycelium of Phellinus linteus. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2005;2:369–74. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Al-Fatimi MAA, Jülich W-D, Jansen R, Lindequist U. Bioactive components of the traditionally used mushroom podaxis pistillaris. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2006;3:87–92. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nek008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Andersson HC, Hajslova J, Schulzova V, Panovska Z, Hajkova L, Gry J. Agaritine content in processed foods containing the cultivated mushroom (Agaricus bisporus) on the Nordic and the Czech market. J Food Addit Contam. 1999;16:439–46. doi: 10.1080/026520399283830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schulzova V, Hajslova J, Peroutka R, Gry J, Andersson HC. Influence of storage and household processing on the agaritine content of the cultivated Agaricus mushroom. Food Addit Contam. 2002;19:853–62. doi: 10.1080/02652030210156340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Friederich U, Fischer B, Luthy J, Hann D, Schlatter C, Wurgler FE. The mutagenic activity of agaritine–a constituent of the cultivated mushroom Agaricus bisporus—and its derivatives detected with the Salmonella/mammalian microsome assay (Ames Test) Z Lebensm Unters Forsch. 1986;183:85–9. doi: 10.1007/BF01041921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Papaparaskeva C, Ioannides C, Walker R. Agaritine does not mediate the mutagenicity of the edible mushroom Agaricus bisporus. Mutagenesis. 1991;6:213–7. doi: 10.1093/mutage/6.3.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Toth B, Gannett P, Rogan E, Williamson J. Bacterial mutagenicity of extracts of the baked and raw Agaricus bisporus mushroom. In Vivo. 1992;6:487–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nagaokaa MH, Nagaoka H, Kondo K, Akiyama H, Maitani T. Measurement of a genotoxic hydrazine, agaritine, and its derivatives by HPLC with fluorescence derivatization in the agaricus mushroom and its products. Chem Pharm Bull. 2006;54:922–4. doi: 10.1248/cpb.54.922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hajslova J, Hajkova L, Schulzova V, Frandsen H, Gry J, Andersson HC. Stability of agaritine - a natural toxicant of Agaricus mushrooms. Food Addit Contam. 2002;19:1028–33. doi: 10.1080/02652030210157691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Toth B. Carcinogenic fungal hydrazines. In Vivo. 1991;5:95–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Toth B, Sornson H. Lack of carcinogenicity of agaritine by subcutaneous administration in mice. Mycopathologia. 1984;85:75–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00436706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Toth B, Taylor J, Mattson B, Gannett P. Tumor induction by 4-(methyl)benzenediazonium sulfate in mice. In vivo. 1989;3:17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stamets P. Notes on nutritional properties of culinary-medicinal mushrooms. Int J Med Mushrooms. 2005;7:103–10. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ohno N, Yadomae T. Mitogenic substances of Bupleuri radix, in traditional herbal medicines for modern times, Bupleurum species, scientific evaluation and clinical applications. In: Sheng-Li, editor. CRC Taylor & Francis; 2006. pp. 159–76. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Izumi S, Ohno N, Kawakita T, Nomoto K, Yadomae T. Wide range of molecular weight distribution of mitogenic substance(s) in the hot water extract of a Chinese herbal medicine, Bupleurum chinense. Biol Pharm Bull. 1997;20:759–64. doi: 10.1248/bpb.20.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ohtsu S, Izumi S, Iwanaga S, Ohno N, Yadomae T. Analysis of mitogenic substances in Bupleurum chinense by ESR spectroscopy. Biol Pharm Bull. 1997;20:97–100. doi: 10.1248/bpb.20.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kidd P. Th1/Th2 balance: the hypothesis, its limitations, and implications for health and disease. Altern Med Rev. 2003;8:223–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Okamoto M, Hasegawa Y, Hara T, Hashimoto N, Imaizumi K, Shimokata K, et al. T-helper type 1/T-helper type 2 balance in malignant pleural effusions compared to tuberculous pleural effusions. Chest. 2005;128:4030–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.6.4030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Knutson KL, Disis ML. Tumor antigen-specific T helper cells in cancer immunity and immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2005;54:721–8. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0653-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sarangi I, Ghosh D, Bhutia SK, Mallick SK, Maiti TK. Anti-tumor and immunomodulating effects of Pleurotus ostreatus mycelia-derived proteoglycans. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006;6:1287–97. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim GY, Lee JY, Lee JO, Ryu CH, Choi BT, Jeong YK, et al. Partial characterization and immunostimulatory effect of a novel polysaccharide-protein complex extracted from Phellinus linteus. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2006;70:1218–26. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70.1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ahn WS, Kim DJ, Chae GT, Lee JM, Bae SM, Sin JI, et al. Natural killer cell activity and quality of life were improved by consumption of a mushroom extract, Agaricus blazei Murill Kyowa, in gynecological cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2004;14:589–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1048-891X.2004.14403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kaneno R, Fontanari LM, Santos SA, Di Stasi LC, Rodrigues FE, Eira AF. Effects of extracts from Brazilian sun-mushroom (Agaricus blazei) on the NK activity and lymphoproliferative responsiveness of Ehrlich tumor-bearing mice. Food Chem Toxicol. 2004;42:909–16. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2004.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fujimiya Y, Suzuki Y, Oshiman K, Kobori H, Moriguchi K, Nakashima H, et al. Selective tumoricidal effect of soluble proteoglucan extracted from the basidiomycete, Agaricus blazei Murill, mediated via natural killer cell activation and apoptosis. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1998;46:147–59. doi: 10.1007/s002620050473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bosch TM, Meijerman I, Beijnen JH, Schellens JH. Genetic polymorphisms of drug-metabolising enzymes and drug transporters in the chemotherapeutic treatment of cancer. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2006;45:253–85. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200645030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Musana AK, Wilke RA. Gene-based drug prescribing: clinical implications of the cytochrome P450 genes. WMJ. 2005;104:61–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Netea MG, Gow NA, Munro CA, Bates S, Collins C, Ferwerda G, et al. Immune sensing of Candida albicans requires cooperative recognition of mannans and glucans by lectin and Toll-like receptors. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1642–50. doi: 10.1172/JCI27114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brown GD. Dectin-1: a signalling non-TLR pattern-recognition receptor. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:33–43. doi: 10.1038/nri1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Saijo S, Fujikado N, Furuta T, Chung S, Kotaki H, Seki K, et al. Dectin-1 is required for host defense against Pneumocystis carinii but not Candida albicans. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:39–46. doi: 10.1038/ni1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sutherland AM, Walley KR, Russell JA. Polymorphisms in CD14, mannose-binding lectin, and Toll-like receptor-2 are associated with increased prevalence of infection in critically ill adults. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:638–44. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000156242.44356.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mullighan CG, Heatley S, Doherty K, Szabo F, Grigg A, Hughes TP, et al. Mannose-binding lectin gene polymorphisms are associated with major infection following allogeneic hemopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2002;99:3524–9. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.10.3524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]