Abstract

We evaluated the effect of acupuncture on NSAID resistant dysmenorrhea related pain [measured according to Visual Analogue Scale (VAS)] in 15 consecutive patients. Pain was measured at baseline (T1), mid treatment (T2), end of treatment (T3) and 3 (T4) and 6 months (T5) after the end of treatment. Substantial reduction of pain and NSAID assumption was observed in 13 of 15 patients (87%). Pain intensity was significantly reduced with respect to baseline (average VAS = 8.5), by 64, 72, 60 or 53% at T2, T3, T4 or T5. Greater reduction of pain was observed for primary as compared with secondary dysmenorrhea. Average pain duration at baseline (2.6 days) was significantly reduced by 62, 69, 54 or 54% at T2, T3, T4 or T5. Average NSAID use was significantly reduced by 63, 74, 58 or 58% at T2, T3, T4 or T5, respectively, and ceased totally in 7 patients, still asymptomatic 6 months after treatment. Our findings suggest that acupuncture may be indicated to treat dysmenorrhea related pain, in particular in those subjects in whom NSAID or oral contraceptives are contraindicated or refused.

Keywords: acupuncture, dysmenorrhea, treatment

Introduction

Dysmenorrhea is a common symptom, reported by ∼25% of women, and by up to 90% of adolescents (1–4). It has been reported to impair current working activity (5,6) in 10% of cases, as well as quality of life (7) and is the main cause of non-attendance at school for adolescents (2,3,5,8), and the first cause for adolescents seeking medical advice (9). Dysmenorrhea is commonly categorized as ‘primary’, i.e. in absence of proven pelvic pathology, or ‘secondary’, i.e. in presence of pelvic pathology: the distinction has mainly a therapeutic purpose, as for cases of secondary dysmenorrhea (e.g. endometriosis or pelvic inflammatory disease) a specific treatment may be offered (10). Pain is the dominating symptom, not controlled by NSAID assumption in 20–25% of cases (11), and several other symptoms, contributing to the pre-menstrual syndrome, may be associated, reaching severe intensity in 3.5–5% of cases (12).

Non-conventional medicine has become very popular in western countries in recent years (13,14). Acupuncture, a traditional Chinese medicine procedure, is well tolerated and free of relevant side effects (15) and has been approved by FDA (16). Acupuncture is commonly used to treat chronic pelvic pain (17), and its use has been recently recommended by the National Institute of Health for the treatment of several diseases, including dysmenorrhea.

The aim of the present study was to assess the efficacy of acupuncture in a consecutive series of women affected by primary or secondary dysmenorrhea (painful menstrual cramps without or with evident pathology to account for them), not controlled by NSAID. Efficacy was measured in terms of pain control, impact on NSAID consumption, and cost-effectiveness.

Methods

Treated Series Characteristics and Treatment Modalities

Between December 2004 and March 2005, a consecutive series of 15 nulliparous patients (age range 13–35, average 27) was enrolled at the ‘Mario Tiengo’ Pain Control Clinic of the Mangiagalli-Regina Elena Hospital of Milan, Italy. Patients were suffering from moderate to severe dysmenorrhea since at least 1 year, had a poor response to NSAID and refused oral contraceptive therapy, which is currently employed as a first line treatment of dysmenorrhea (4,18,19). All patients underwent careful anamnesis, pain evaluation, transvaginal ultrasound (transabdominal if virgo), and CA125 dosage in the second part of menstrual cycle. Patients features at presentation are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patients characteristics

| Patient | Age | Menarche | Dysmenorrhea | Anamnesis | US | US report | Ca-125 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 33 | 12 | Secondary | Sterility | TVa | Endometriomac | 89 |

| 2 | 29 | 13 | Primary | Negative | TV | Negative | 13 |

| 3 | 35 | 14 | Secondary | Hyperthyroidism | TV | Endometriomac | 67 |

| Appendicectomy | |||||||

| 4 | 25 | 12 | Secondary | Negative | TV | Endometriomac | 78 |

| 5 | 27 | 12 | Primary | Negative | TV | Negative | 11 |

| 6 | 33 | 13 | Secondary | Appendicectomy | TV | Suspicious adhesive syndrome | 36 |

| Lumbar hernia | |||||||

| 7 | 35 | 14 | Secondary | Sterility | TV | Suspicious adenomioma | 35 |

| 8 | 25 | 12 | Primary | Chronic gastritis | TV | Negative | 10 |

| 9 | 13 | 10 | Primary | Appendicectomy | TAb | Negative | 6 |

| 10 | 27 | 12 | Secondary | Nervous anorexia | TV | Pelvic varicocele | 8 |

| 11 | 29 | 11 | Secondary | Appendicectomy | TV | Suspicious adhesive syndrome | 7 |

| 12 | 32 | 14 | Primary | Negative | TV | Negative | 19 |

| 13 | 35 | 15 | Primary | Negative | TV | Negative | 28 |

| 14 | 18 | 14 | Secondary | Appendicectomy | TV | Suspicious adhesive syndrome | 6 |

| 15 | 13 | 11 | Primary | Negative | TA | Negative | 7 |

aTV, transvaginal, bTA, transabdominal, cconfirmed at laparoscopy.

All patients were given 8 weekly acupuncture sessions, for a total duration of 2 months. Needle positioning was based on conventional diagnostic criteria of traditional Chinese medicine. Sterile needles were positioned for 30 min at a variety of acupoints, namely KI-3, LV-3, SP-4, ST-36, ST-25, ST-29, ST-30, REN-4, REN-6, BL-62, HT-7, LI-4, PC-6 and ZI GONG extra point. (20). No limitation to additional NSAID use was required, if necessary.

Results Assessment Methodology

The efficacy of acupuncture was assessed through Visual Analogue Scales (VAS), a self assessment scale ranging from 0 to 10, where the patient was requested to indicate the point most representative of pain intensity, from score 0 (no pain) to score 10 (pain as bad as it could be), chosen for its simplicity (21).VAS was determined at five different points in time, namely baseline (T1), mid treatment (T2), end of treatment (T3), and 3 (T4) and 6 months (T5) after the end of treatment. Overall NSAID use (number of assumed doses), and duration of pain (days), were determined at the same points in time. Cost analysis was attempted, based on average cost of baseline NSAID (Nimesulide®) use (€0.1563/single dose), assumed to be stable in absence of acupuncture, for a period of 8 months (equivalent to 2 months of acupuncture treatment + 6 months of follow-up), compared with (i) the cost of NSAID documented use since treatment started, plus (ii) the cost of the acupuncture procedure (€17.50 per session, according to Regional Health Service tariff).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance (P < 0.05) of observed results was determined by analyzing the distribution of pain intensity (VAS), pain duration and NSAID consumption at T1 (prior to treatment) as compared with T3 (end of treatment) or T5 (6 months after end of treatment) with Wilcoxon's signed rank test, using STATA 8.0 (www.stata.com) software.

Results

Treatment Effects on Pain

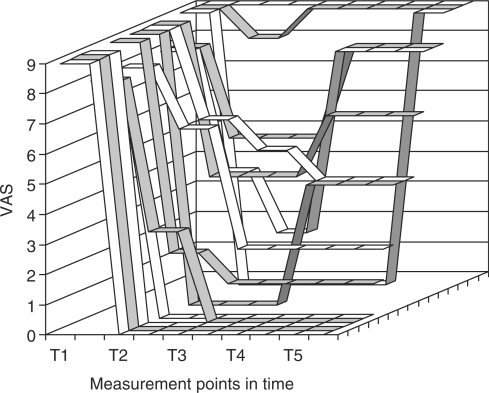

All patient's completed treatment and follow-up. Overall treatment response (substantial reduction of pain and NSAID assumption was observed in 13 of 15 patients (87%). Overall, pain remained unchanged, was only temporarily reduced, was permanently reduced or disappeared and did not recur in 2, 3, 3 or 7 patients, respectively. Detailed data on pain over time are given in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Pain response over time. Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) values in single patients at different points in time (T1 = baseline, T2 = mid treatment, T3 = end treatment, T4 = 3 months after treatment, T5 = 6 months after treatment).

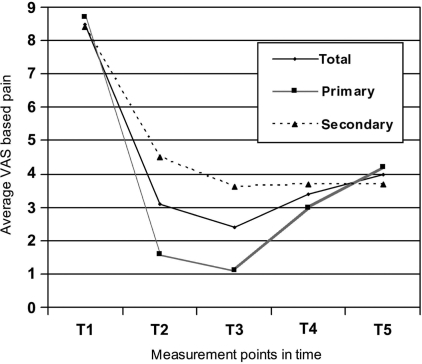

Figure 2 shows the average effects of treatment on pain at different time points: VAS based pain intensity was reduced with respect to baseline value (average VAS = 8.5), namely by 64, 72, 60 or 53% at T2, T3, T4 or T5, respectively. Greater reduction of pain was observed for primary (82, 88, 66 and 51%) as compared with secondary dysmenorrhea (47, 57, 56 and 56%). Pain intensity reduction with respect to T1 was statistically significant at T3 (P = 0.0008) and at T5 (P = 0.0022).

Figure 2.

Average results of treatment on pain, measured at VAS, at different points in time and according to dysmenorrhea type (primary or secondary).

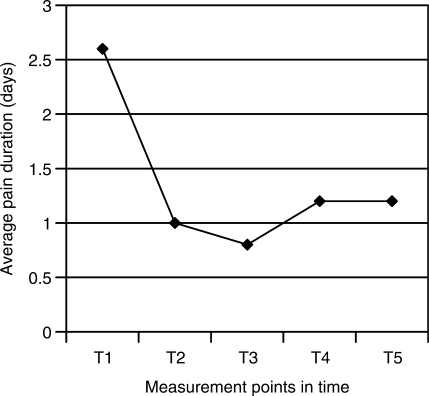

Figure 3 shows treatment results according to pain duration (days) at different points in time. Average pain duration at baseline (2.6 days) was reduced by 62, 69, 54 or 54% at T2, T3, T4 or T5, respectively. Pain duration with respect to T1 was significantly reduced at T3 (P = 0.0004) and at T5 (P = 0.0016).

Figure 3.

Results of treatment on average duration (days) of pain, at different points in time.

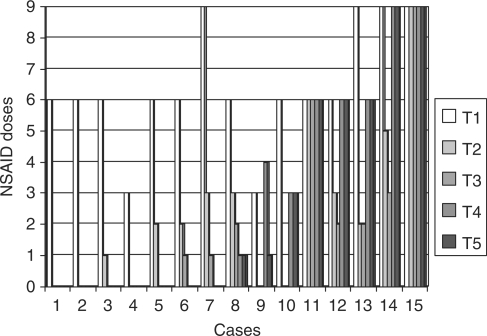

Treatment Effects on NSAID Consumption

NSAID use was recorded in all patients at baseline. Average NSAID use was reduced by 63, 74, 58 or 58% at T2, T3, T4 or T5, respectively, and ceased totally in 7 patients, still asymptomatic 6 months after treatment. Data are summarized in Fig. 4. NSAID average consumption with respect to T1 was significantly reduced at T3 (P = 0.0008) and at T5 (P = 0.0015).

Figure 4.

Total use of anti-pain drugs before, during, and after acupuncture treatment (T1 = baseline, T2 = mid treatment, T3 = end treatment, T4 = 3 months after treatment, T5 = 6 months after treatment).

No side effects of acupuncture were observed or reported by patients.

Cost Analysis

Although acupuncture substantially reduced NSAID use, cost analysis showed a higher cost for the acupuncture policy (€2,148.14) as compared with predicted cost of NSAID use (€120.03).

Discussion

The present study, though limited to a single treatment arm, shows a favorable effect of acupuncture in controlling the duration and intensity of moderate/severe dysmenorrhea related pain (VAS ≥ 6) over time, thus confirming previous reports of non-controlled studies (22) and of two controlled trials of acupuncture reported thus far (23,24).

Pain control (minor or absent, VAS ≤ 2) obtained at the end of treatment is maintained up to 6 months in approximately 50% of cases, which confirms that acupuncture obtains more than just a temporary symptomatic effect. As a placebo effect cannot be excluded, the observed effects might be at least partially attributed to patient's expectation. Nevertheless, the observed large, statistically significant, reduction of pain suggests a true therapeutic effect of acupuncture, as the placebo effect of any treatment is not likely to occur in more than 50% of cases.

Substantial reduction of NSAID use was also evidenced as a consequence of pain control by acupuncture: this may be a further benefit, as NSAID side effects (25) may be reduced. Overall costs, however, were not reduced, due to the higher cost of acupuncture as compared with NSAID. This confirms recent reports of a higher cost of acupuncture as compared with conventional treatments (26).

Our findings suggest that acupuncture may be indicated to treat dysmenorrhea related pain, in particular in those subjects in whom NSAID or oral contraceptives are contraindicated or refused, pain control being substantially higher than what might be expected only with a placebo effect. The definition of more precise criteria for treatment and its modalities (e.g. duration and intensity) should be the object of further studies allowing for a longer follow-up.

References

- 1.Latthe P, Latthe M, Say L, Gulmezoglu M, Khan KS. WHO systematic review of prevalence of chronic pelvic pain: a neglected reproductive health morbidity. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:177. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harel Z. A contemporary approach to dysmenorrhea in adolescents. Paediatr Drugs. 2002;4:797–805. doi: 10.2165/00128072-200204120-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slap GB. Menstrual disorders in adolescence. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2003;17:75–92. doi: 10.1053/ybeog.2002.0342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Durain D. Primary dysmenorrhea: assessment and management update. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2004;49:520–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dawood MY. Dysmenorrhea. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1990;33:168–78. doi: 10.1097/00003081-199003000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dawood MY. Primary dysmenorrhea: advances in phatogenesis and management. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:428–41. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000230214.26638.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Proctor M, Farquhar C. Diagnosis and management of dysmenorrhea. Br Med J. 2006;332:1134–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7550.1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones GL, Kennedy SH, Jenkinson C. Health related quality of life measurement in women with common benign gynaecologic conditions: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:501–11. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.124940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deligeoroglou E, Tsimaris P, Deliveliotou A, Christopoulos P, Creatsas G. Menstrual disorders during adolescence. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2006;3(Suppl 1):150–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tzafettas J. Painful menstruation. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2006;3(Suppl 1):160–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howard FM, Perry P, Carter J, El-Minawi AM. Pelvic Pain Diagnosis and Management. Philadelphia: Lippincot Williams and Wilkins; 2000. pp. 100–7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.American College of Obstetricians, & Gynecologist. ACOG committee opinion: premenstrual syndrome. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1995;50:80–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corney RH, Stanton R. A survey of 658 women who report symptoms of premenstrual syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 1991;35:471–82. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(91)90042-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fugh-Berman A, Kronenberg F. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in reproductive-age women: a review of randomized controlled trials. Reprod Toxicol. 2003;17:137–52. doi: 10.1016/s0890-6238(02)00128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adams K, Assefi N. Applications of acupuncture to women's health. Prim Care Update Ob/Gyns. 2001;8:218–25. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beal MW. Acupuncture and acupressure application to women's reproductive health care. J Nurs Midwifery. 1999;44:217–30. doi: 10.1016/s0091-2182(99)00054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Capodice JL, Bemis DL, Buttyan R, Kaplan SA, Katz AE. Complementary and alternative medicine for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2005;2:495–501. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braunstein JB, Hausfeld J, Hausfeld J, London A. Economics of reducing menstruation with trimonthly-cycle oral contraceptive therapy: comparison with standard-cycle regimens. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:699–708. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00738-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Proctor ML, Roberts H, Farquhar CM. Combined oral contraceptive pill as treatment for primary dysmenorrhea. Cochraine Database Syst Rev. 2001;4:CD002120. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beijing College of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Essential of Chinese Acupuncture. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press; 1980. pp. 375–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wyatt KM, Dimmock PW, Hayes-Gill B, Crowe J, O'Brien PM. Menstrual symptometrics: a simple computer-aided method to quantify menstrual cycle disorders. Fertil Steril. 2002;78:96–101. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)03161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsenov D. The effect of acupuncture in dysmenorrhea. Akush Ginekol (Sofia) 1996;35:24–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Helms JM. Acupuncture for the management of primary dysmenorrhea. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;69:51–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas M, Lundeberg T, Bjork G, Lundstrom-Lindstet V. Pain and discomfort in primary dysmenorrhea is reduced by preemptive acupuncture or low-frequency TENS. Eur J Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;4:71–6. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dawood MY. Dysmenorrhea. J Reprod Med. 1985;30:154–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Canter PH, Thompson Coon J, Ernst E. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. Cost-effectiveness of complementary therapies in the United Kingdom–a systematic review. doi:10.1093/ecam/nel044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]