Abstract

Objectives

With significant differences in risks of renal failure in different ethnic/racial groups in the U.S., we sought to determine if disparities exist in reporting lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in Non-Hispanic White (NHW), Mexican American (MA), and African American (AA) men. Epidemiological studies in AA men suggest they may have more LUTS compared to NHWs, but little is known about symptom prevalence among MA men.

Methods

Data were collected from a prospective, community-based cohort assembled to study risk factors associated with prostate cancer. Measures included demographics, prostate specific antigen (PSA), body mass index (BMI), and family history of prostate cancer. LUTS severity was assessed in 2,804 (1,485 NHW, 964 MA, 355 AA) men without prostate cancer using the American Urological Association Symptom Index (AUASI).

Results

No significant difference (p = 0.998) was seen in prevalence of moderate or severe LUTS in NHW (34%), MA (34%), and AA (33%) men. No differences were found in either obstructive or irritative symptoms among the three groups. Age, PSA level, BMI, and family history did not affect symptom severity.

Conclusions

Rates of moderate to severe LUTS symptoms in this cohort were similar to those in other community-based populations of NHW men. Lower rates of moderate/severe symptoms were noted in AA men than previously reported. MA men had similar degrees of LUTS as the general population, and with their increased risk for diabetes and renal disease, in-depth study of this population is warranted.

Keywords: ethnicity, lower urinary tract symptoms, men

INTRODUCTION

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a ubiquitous condition of American men and is often associated with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS).1 The presence of LUTS has been found to adversely affect quality of life and lead men to seek medical and surgical therapy.2, 3

Few studies have examined severity of LUTS among ethnic groups of community-dwelling men. Among Non-Hispanic White (NHW) men, the natural progression of LUTS measured by American Urological Association Symptom Index (AUASI) score is manifested by an increase in symptoms with age: 0.18 points per year of follow-up.4 In an analysis of a population-based sample in Michigan where African American (AA) men (n= 369) were compared to NHW men (n = 2111), 41% of the AA men had moderate to severe AUASI scores compared to 34% of NHW men.5 Potential risk factors for increased LUTS in AA men include smoking, alcohol use, hypertension, diabetes, and low income. 6 Little is known about severity of LUTS in Hispanic American men, specifically Mexican American (MA) men, in comparison to other ethnic groups. Most published reports suffer from selection bias due to inclusion of men referred from Urology clinics or the highly-selected men included in placebo arms of treatment trials.

BPH may be a risk factor for chronic renal failure.7 A population-based study demonstrated that chronic kidney disease was associated with bladder outlet obstruction (low peak flow rates, high LUTS reporting, and high post void residual volumes), but no association was seen when taking into account prostatic size (measured by prostate volume and serum PSA).8 Proposed mechanisms for chronic kidney disease in men with BPH may be related to bladder outlet obstruction which results in bladder changes caused by acute or chronic urinary retention and recurrent urinary tract infections.7 Evidence that pharmacologic therapy with finasteride reduces the risk of clinical progression of BPH raises the intriguing question whether such therapy could reduce the risk of renal disease related to LUTS. 9 Among AA men in whom LUTS may be differentially manifested, there are increased rates of end stage renal disease.10 With the significantly-increased risk of diabetes in Hispanic and AA men, it is possible that a similar rates of LUTS may contribute to the high risk of diabetic nephropathy in this ethnic group.11 These disparities may be exacerbated by ethnic-specific rates of access to health care services.10, 12 We therefore assessed the frequency of LUTS among three ethnic groups in the subject cohort of the San Antonio Center of Biomarkers of Risk for Prostate Cancer (SABOR).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

SABOR was established in March 2001 as a Clinical and Epidemiologic Validation Center (CEVC) of the Early Detection Research Network (EDRN), funded through the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The objectives of the EDRN CEVC's are to expand and develop existing biorepositories and associated clinical databases to develop and test the performance of new biomarkers for cancer. The goal of SABOR is to establish a large multiethnic population to study behavioral, genetic, and other markers of risk of prostate cancer. Healthy men without a history of prostate cancer are eligible for participation. SABOR is approved through The University of Texas Health Science Center's Institutional Review Board. After informed consent, participants complete a series of instruments that collect demographical data, diet, family history, racial/ethnicity determination, and AUASI.13 Men with Spanish language preferences were given the instruments in Spanish.14

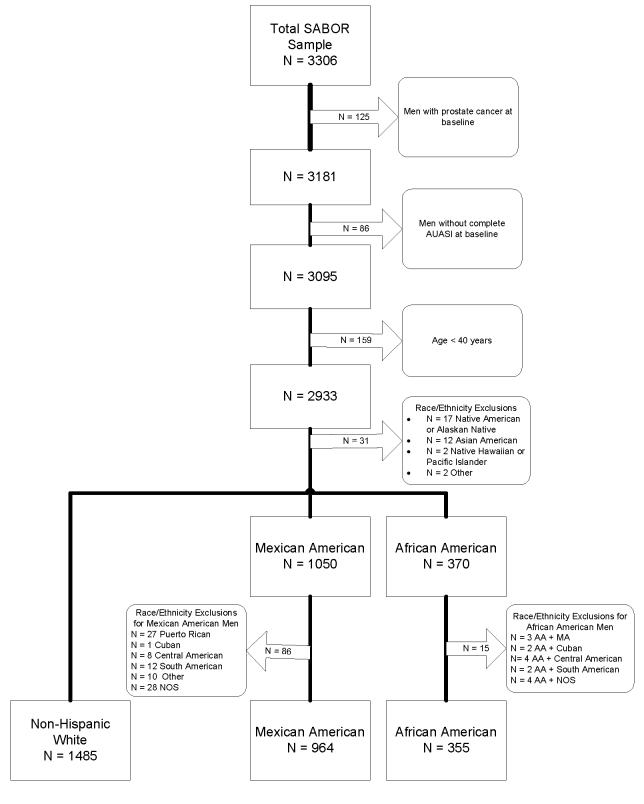

SABOR participants self-selected one or more of the following racial categories based on the United States Census Bureau designations. The final study population is outlined in Figure 1. Men were excluded if they had biopsy-confirmed prostate cancer at baseline or at the follow-up visit (n=125, 3.9%), had incomplete baseline AUASI scores (n = 86, 2.7%), or were under 40 years of age (n= 159) yielding 2804 men for analysis, comprising 1485 NHW, 964 MA, and 355 AA. Men of multi-racial and mixed ethnicity were also excluded (n = 101) from the final analyses (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram for Inclusion of Participants for SABOR

Measurements

The primary outcome measure in this study was LUTS severity as measured by the AUASI scores for each ethnic sub-group (NHW, MA, AA).13 Subjects' self-reported data were used for the AUASI.15 AUASI scores were then categorized as mild (7 or less), moderate (8 to 19), and severe (20 or more).13 Storage and emptying subscores of the AUASI were also analyzed for differences according to race/ethnicity. Questions on storage symptoms included symptoms of urgency, frequency, and nocturia. Questions used to quantify emptying symptoms included concepts of straining, difficulty with emptying, intermittency, and having a weak urinary stream. Subjects also provided biologic samples which included PSA serum testing (Abbott IMX assay) and prostate biopsy/prostatectomy samples (for individuals with an indication for prostate biopsy or diagnosed with prostate cancer). All men underwent a clinical physical examination including digital rectal exam (DRE), height, and weight. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as kg/m2. Subjects self-reported any first-degree relative family history of prostate cancer, defined as whether a father or brother was ever diagnosed with prostate cancer.

Statistical Analysis

Total AUASI scores were calculated and evaluated for differences by race and age categories using univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA). The Kruskal-Wallis chi-square rank sum test was used to perform the corresponding dependence on age and race in the analyses of AUASI severity scores, defined as Mild: ≤ 7, Moderate 8—19, and Severe ≥ 20. Stratified (subset) analyses for racial differences in different age groups for the AUASI total scores and severity scores were similarly performed using ANOVA and the chi-square test. Multivariable linear regression was used to evaluate the effect of race/ethnicity on total AUASI, adjusting for age, PSA, family history as well as potential interactions between these confounders. Mean PSA values were used in the analyses as a proxy for prostate volume.16 All statistical analyses were performed with STATA 8.2 (College Station, Texas) at the 0.05 significance level.

RESULTS

Characteristics for the 2804 SABOR participants used in the analysis are given in Table 1. Significant differences among the three ethnic groups comprising 1485 NHW, 964 MA, and 355 AA included age, mean PSA, and prevalence of family history for prostate cancer. The average age of men in this study was 57.5 years, NHW men being significantly (p<0.001) older (60.1 years) in average age than either AA (52.8 years) or MA men (55.3 years). Perhaps due to these differences, AA men had significantly (p=0.011) lower mean PSA scores (1.1 ng/mL) compared to NHWs (1.4 ng/mL) and MA (1.4 ng/mL). NHW men had a higher prevalence (20%) of a family history of prostate cancer than did AA (17%) or MA (16%) men (p=0.023).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics and AUASI scores by race/ethnicity

| Characteristic | All (n=2804) |

Non-Hispanic Whites (n=1485) |

Mexican Americans (n=964) |

African Americans (n=355) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD | 57.5 ± 9.8 | 60.1 ± 9.8 | 55.3 ± 9.1 | 52.8 ± 8.5 | <0.001* |

| Age by decade | |||||

| 40-49 years, n (%) | 614 (21.9) | 194 (13.1) | 279 (28.9) | 141 (39.7) | <0.001† |

| 50-59 years, n (%) | 1068 (38.1) | 558 (37.6) | 373 (38.7) | 137 (38.6) | |

| 60-69 years, n (%) | 766 (27.3) | 467 (31.5) | 239 (24.8) | 60 (16.9) | |

| 70-79 years, n (%) | 302 (10.8) | 224 (15) | 62 (6.4) | 16 (4.5) | |

| 80+ years, n (%) | 54 (1.9) | 42 (3) | 11 (1.1) | 1 (0.3) | |

| BMI., mean ± SD | 28.9 ± 4.8 | 28.8 ± 4.9 | 29.1 ± 4.8 | 29.0 ± 4.6 | 0.166* |

| PSA (ng/mL), mean ± SD |

1.4 ± 1.6 | 1.4 ± 1.6 | 1.4 ±1.6 | 1.1 ± 1.3 | 0.012* |

| Family history of prostate cancer, n (%) |

503 (18) | 294 (20) | 150 (16) | 59 (17) | 0.023† |

| AUASI by categories | |||||

| Mild, n (%) | 1863 (66.4) | 986 (66.4) | 639 (66.3) | 238 (67.0) | 0.998† |

| Moderate, n (%) | 786 (28.0) | 416 (28.0) | 272 (28.2) | 98 (27.6) | |

| Severe, n (%) | 156 (5.6) | 84 (5.7) | 53 (5.5) | 19 (5.4) | |

| AUASI, mean ± SD | 6.9 ± 6.2 | 6.9 ±6.2 | 7.0 ±6.3 | 6.8 ±6.0 | 0.812† |

| Emptying AUASI scores, mean ± SD |

3.8 ± 2.9 | 3.6 ±3.0 | 3.8 ±2.9 | 3.8 ± 2.9 | 0.874† |

| Storage AUASI scores, mean ± SD |

3.1 ± 4.0 | 3.0 ±3.9 | 3.2 ±4.1 | 3.0 ± 3.4 | 0.475† |

KEY: BMI = Body mass index, kg/m2; AUASI = American Urological Association Symptom Index; PSA = prostate specific antigen, SD = standard deviation

Tests of significant differences calculated by one-way ANOVA testing between races.

Tests of significant differences in frequencies based on chi-square test for differences by race.

One-third of men in each ethnic group in this community-dwelling population had moderate to severe lower urinary tract symptoms (34% in NHW, 34% in MA, and 33% in AA). No difference was found among the three ethnic groups in the storage and emptying symptom subscores of the AUASI. No significant difference in distributions of mild, moderate, and severe symptoms, using the AUASI, was found among ethnic groups nor was there a difference in mean scores (Table 1).

In subgroup analyses, no significant differences were seen in either mean AUASI score according to age decade or AUASI score according to symptoms severity (Table 2). AA men aged 70-79 years had higher mean AUASI scores than the NHW or MA men in this age group, but the difference was not significant (p = 0.07). AUASI scores varied in all other age decades and did not increase linearly with age (p = 0.8) or by race/ethnicity (p = 0.8). In the regression model with total AUASI score adjusted for age and racial/ethnic group, the interaction between age and racial/ethnic group was also not significant (p = 0.7).

Table 2.

Mean total American Urological Association Symptom Index scores and severity in SABOR stratified by race and age

| Total, n = 2804 | 40-49 years, n = 614 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHW n=1485 |

MA n=964 |

AA n=355 |

p value | NHW n=194 |

MA n=279 |

AA n= 141 |

p value | ||

| AUASI score, mean ±SD |

6.9 ±6.2 | 7.0 ±6.3 | 6.8 ±6.0 | 0.8* | 6.2 ±5.2 | 6.9 ±6.5 | 7.0 ±6.3 | 0.3* | |

| AUASI severity | |||||||||

| Mild (≤7) | 986 (66) | 639 (66) | 238 (67) | 0.9† | 137 (71) | 187 (67) | 96 (68) | 0.7† | |

| Moderate (8-19) | 416 (28) | 272 (28) | 98 (28) | 53 (27) | 79 (28) | 36 (26) | |||

| Severe (≥20) | 84 (6) | 53 (6) | 19 (5) | 4 (2) | 13 (5) | 9 (6) | |||

| 50-59 years, n = 1068 | 60-69 years, n = 766 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHW n= 558 |

MA n=373 |

AA n=137 |

p value | NHW n=467 |

MA n=239 |

AA n=60 |

p value | ||

| AUASI score, mean ±SD |

7.2 ±6.4 | 7.0 ±6.4 | 6.7 ±5.6 | 0.7* | 6.9 ±6.3 | 7.0 ±6.1 | 5.8 ±5.3 | 0.4* | |

| AUASI severity | |||||||||

| Mild (≤7) | 357 (64) | 248 (66) | 91 (66) | 0.7† | 311 (67) | 158 (66) | 43 (72) | 0.7† | |

| Moderate (8-19) | 164 (29) | 104 (28) | 40 (29) | 129 (28) | 68 (29) | 15 (25) | |||

| Severe (≥20) | 37 (7) | 21 (6) | 6 (5) | 27 (6) | 13 (5) | 2 (8) | |||

| 70-79 years, n = 302 | 80+ years, n = 54 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHW n=224 |

MA n=62 |

AA n=16 |

p value | NHW n=42 |

MA n=11 |

AA n=1 |

p value | ||

| AUASI score, mean ±SD |

6.5 ±6.2 | 7.5 ±6.5 | 10.1 ±7.4 | 0.07* | 6.8 ±5.5 | 6 ±6.6 | 7 | 0.9* | |

| AUASI severity | |||||||||

| Mild (≤7) | 154 (69) | 38 (61) | 7 (44) | 0.2† | 27 (64) | 8 (73) | 1 (100) | 0.8† | |

| Moderate (8-19) | 56 (25) | 19 (31) | 7 (44) | 13 (31) | 2 (18) | 0 (0) | |||

| Severe (≥20) | 14 (6) | 5 (8) | 2 (13) | 2 (5) | 1 (9) | 0 (0) | |||

Key: NHW = Non-Hispanic Whites, MA = Mexican Americans, AA = African Americans, AUASI = American Urological Association Symptom Index, SD = standard deviation

Tests of significant differences calculated by one-way ANOVA testing between races by age categories.

Tests of significant differences calculated by Kruskal-Wallis chi-square test for AUASI severity based within age categories.

The majority of participants (66%) had mild symptoms (≤ 7), with moderate symptoms (8-19) in 28%, and severe symptoms (≥20) in 6%. When further examining the individual AUASI questions from the men, frequency and nocturia were the most common symptoms reported. No significant differences were noted in nocturia reporting by age decade (p = 0.07) or for any of the other symptoms according to age group (data not shown). It is interesting to note that men 80 years of age did not report symptoms of storage (urgency and frequency) more often than other age groups.

COMMENT

Of 2,804 participants in this analysis, including a large percentage of AA men (12.7%) and MA men (34.4%), we found no significant difference in the rate of LUTS compared to NHW. Age did not appear to impact symptom severity among the three ethnic groups when analyzed by age decade. Overall, symptom severity was similar to other population and community-based studies in NHW.1 Moderate or severe symptoms were reported in 34% of NHW, 34% of MA, and 33% of AA in this cohort. By comparison, other studies have reported a greater degree of symptoms in AA men (41%) than in NHW men (34%).5 In a national study of health professionals, there was no increased risk for BPH in AAs compared to NHWs and no difference in symptom severity in age-adjusted relative risk among AA and Asian Americans in comparison to NHW.17 Very little is known about symptom severity in MAs.

In an analysis of age-specific prevalence of LUTS in this cross-sectional study, we found no significant increases in symptom severity by age decade. This may be due to the relatively small number men over 70 years old in the study and within the different race/ethnicity as well as age-decade groups. Although NHW men had increased mean AUASI scores in the middle age decades and MA men had increased mean AUASI scores among each age decade, these differences were small in magnitude and not statistically significant (p = 0.822). In particular, no significant trend was seen among AA men according to age decade in this study. In another longitudinal study of AA men, mean AUASI scores at baseline and follow-up were not statistically different, although a progression of symptom severity was noted across all ages.5

To our knowledge, this is the first community-based study that examines the prevalence of LUTS symptoms in these three ethnic groups. Although the MA men in this study were younger than NHW, we hypothesized that MA would have lower symptoms than either of the other two ethnic groups. Surprisingly, they had equal degrees of LUTS severity as NHW men, even after adjusting for age, which did not impact on severity of symptoms. With the greater risk of diabetes in MAs and faster progression rates of chronic renal impairment to end-stage renal disease among AAs, these ethnic groups may therefore be at higher risk of BPH-related chronic renal failure.10, 11, 18 Despite changes in guidelines, eliminating the requirement for monitoring of serum creatinine in men presenting for evaluation for BPH, it may be important to screen certain high risk patients for renal function changes to further evaluate for bladder outlet obstruction.8, 10, 19 In both AAs and MAs, other factors could contribute to the similarities seen in symptom reporting in comparison to NHWs.

Limitations to this study include data on the socioeconomic status or health status of the men in this study. The men in both minority groups, AA and MAs, may not have discussed their urologic symptoms with their physicians and may not recognize how their symptoms relate to risk of prostate cancer. This effect may artificially lower symptom score reporting in these two groups. However, if these men were more likely to participate because of the degree of LUTS, they may more likely to report higher AUASI scores. In contrast, others have found that sociodemographic and health status factors may not influence AUASI scores in men with LUTS.20 In the US among AA men, those with higher incomes were less likely to report LUTS.6 We were unable to ascertain if certain participation biases existed for enrollment in this study.

Another limitation of this study is the inclusion of men regardless of treatment (medication or prior surgery for BPH). Given that prevalence rates of BPH are high and treatments are common, this may affect the overall AUASI scores by reducing actual differences, especially due to treatment. If health disparities exist in access to care in this community setting, more NHW men may have been treated for BPH and thus may report lower AUASI scores than prior to treatment. However, our results show similar rates of symptom severity reported on the AUASI for NHW men in comparison to other studies where men who had treatment for BPH were eliminated from the analysis.1,5 Conversely, due to perceived risk of prostate disease, AA men may have been more likely to seek evaluation and treatment for LUTS. We were unable to determine the impact of treatment for BPH in this cohort.

We were also unable to identify risk factors for men with more severe symptoms. Other studies have proposed that the presence of co-morbid diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease may have a role in LUTS, as well as smoking and alcohol consumption, which would require larger sample sizes than here to adequately assess.6

CONCLUSIONS

In this cross-sectional, community-based prospective study for risk of developing prostate cancer, we demonstrated no racial disparities in reporting LUTS among NHW, AA, and MA participants. Our observations may lead to further evaluation for racial disparities in MA men and further data are needed related to longitudinal symptom progression in this group. Clinical practice and guidelines for screening men presenting with BPH may require modification if LUTS reporting is the same among ethnic groups who may have increased rates of other co-morbidities.

Acknowledgements

Supported by NCI grant #5UO1CA86402-04

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jacobsen SJ, Girman CJ, Lieber MM. Natural history of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. 2001;58(6 Suppl 1):5–16. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Girman CJ, Jacobsen SJ, Tsukamoto, et al. Health-related quality of life associated with lower urinary tract symptoms in four countries. Urology. 1998;51(3):428–436. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00717-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberts RO, Chute CG, Rhodes T, et al. Natural history of prostatism: Worry and embarrassment from urinary symptoms and health care-seeking behavior. Urology. 1994;43:621–628. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(94)90174-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobsen SJ, Girman CJ, Guess HA, et al. Natural history of prostatism: longitudinal changes in voiding symptoms in community dwelling men. J Urol. 1996;155(2):595–600. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)66461-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarma AV, Wei JT, Jacobson DJ, et al. Comparison of lower urinary tract symptom severity and associated bother between community-dwelling black and white men: the Olmsted County Study of Urinary Symptoms and Health Status and the Flint Men's Health Study. Urology. 2003;61(6):1086–1091. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00154-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joseph MA, Harlow SD, Wei JT, et al. Risk factors for lower urinary tract symptoms in a population-based sample of African-American men. Am J of Epidemiol. 2003;157(10):906–914. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rule AD, Lieber MM, Jacobsen SJ. Is benign prostatic hyperplasia a risk factor for chronic renal failure? J Urol. 2005;173:691–696. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000153518.11501.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rule AD, Jacobson DJ, Roberts RO, et al. The association between benign prostatic hyperplasia and chronic kidney disease in community-dwelling men. Kidney International. 2005;67:2376–2382. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McConnell JD, Roehrborn CG, Bautista OM, et al. The long-term effect of doxazosin, finasteride, and combination therapy on the clinical progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2387–2398. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clase CM, Garg AX, Kiberd BA. Prevalence of low glomerular filtration rate in nondiabetic Americans: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1338–1349. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000013291.78621.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris MI, Flegal KM, Cowie CC, et al. Prevalence of diabetes, impaired fasting glucose, and impaired glucose tolerance in U.S. adults. The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(4):518–522. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.4.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ifudu O, Dawood M, Iofel Y, et al. Delayed referral of black, Hispanic, and older patients with chronic renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999;33:728–733. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(99)70226-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barry MJ, Fowler FJ, Jr, O'Leary MP, et al. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol. 1992;148:1549–1557. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36966-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Badia X, Garcia-Losa M,, Dal-Re, et al. Validation of a harmonized Spanish version of the IPSS: evidence of equivalence with the original American scale. Urology. 1998;52:614–620. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rhodes T, Girman CJ, Jacobsen SJ, et al. Does the mode of questionnaire administration affect the reporting of urinary symptoms? Urology. 1995;46:341–345. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(99)80217-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roehrborn CG, Boyle P, Gould AL, Waldstreicher J. Serum prostate-specific antigen as a predictor of prostate volume in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. 1999;53:581–589. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00655-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Platz EA, Kawachi I, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Giovannucci E. Race, ethnicity and benign prostatic hyperplasia in the health professionals follow-up study. J Urol. 2000;163:490–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsu CY, Lin F, Vittinghoff E, Shlipak MG. Racial differences in the progression from chronic renal insufficiency to end-stage renal disease in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:2902–2907. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000091586.46532.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Committee, AUAPG AUA guideline on management of benign prostatic hyperplasia (2003). Chapter 1: Diagnosis and treatment recommendations. J Urol. 2003;170:530–547. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000078083.38675.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Badia X, Rodriguez F, Carballido J, et al. Influence of sociodemographic and health status variables on the American Urological Association symptom scores in patients with lower urinary tract symptoms. Urology. 2001;57:71–77. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00894-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]