Abstract

Data from a survey of 200 young adults assessed whether the early nonshared environment, specifically parental differential treatment, was associated with romantic relationship distress through its effects on sibling jealousy, attachment styles, and self-esteem. Individuals who received equal affection from their parents in comparison to their sibling reported equal jealousy between themselves and their sibling, had higher self-esteem, more secure attachment styles, and less romantic relationship distress. Receiving differential parental affection, regardless of whether the participant or their sibling was favored, was associated with more negative models of self and others, which in turn were associated with greater romantic relationship distress. Results indicate that early within-family experiences may be particularly relevant for later healthy romantic relationship functioning.

The achievement of intimacy in close relationships is considered a central developmental task in the early years of adulthood (W. A. Collins & Sroufe, 1999; Conger, Cui, Bryant, & Elder, 2000; Erikson, 1968). The failure to establish and maintain such high-quality relationships is associated with poorer well-being. In particular, individuals in unhappy relationships are more likely to suffer poor physical and mental health, even if their romantic relationships are stable (Beach, Katz, Kim, & Brody, 2003; Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001). Given the importance of romantic relationship quality for well-being, researchers have sought to understand the developmental roots of the ability to both initiate and maintain high-quality romantic relationships (Conger et al., 2000). Research has demonstrated that experiences in the early familial environment contribute to romantic relationship functioning, such that individuals who grow up in families characterized by nurturing parenting have higher quality romantic relationships as adults than do individuals who grow up with parents characterized as distant or cold (Black & Schutte, 2006; Donnellan, Larsen-Rife, & Conger, 2005).

Although research has recognized the importance of early childhood experiences for the development of competence in intimate relationships, only recently have researchers begun to examine the sibling relationship as being a significant aspect of the early family environment (L. R. Brody, Copeland, Sutton, Richardson, & Guyer, 1998). The roots of this emerging interest in sibling influences can be traced to the investigation of the developmental impact of the nonshared environment, defined as any environmental experience that differs for children growing up in the same family (i.e., being treated differently by parents and one's own siblings; Baker & Daniels, 1990; Daniels & Plomin, 1985). These differences can be quite pronounced as the differential experiences of children within the same family are often greater than the experiences of children from different families (Plomin & Daniels, 1987). These differences, whether perceived or actual, have important implications for individual adjustment at multiple developmental stages and in multiple domains (L. R. Brody et al., 1998; Sheehan & Noller, 2002; Volling & Elins, 1998). Despite the importance of the early nonshared environment for development, there is a comparative absence of research examining how the early nonshared environment is associated with romantic relationship adjustment. This link may be especially relevant, given that the sibling relationship may provide an important context in which young adults learn social skills and interaction styles that aid in the development and maintenance of satisfying interpersonal relationships (Yeh & Lempers, 2004).

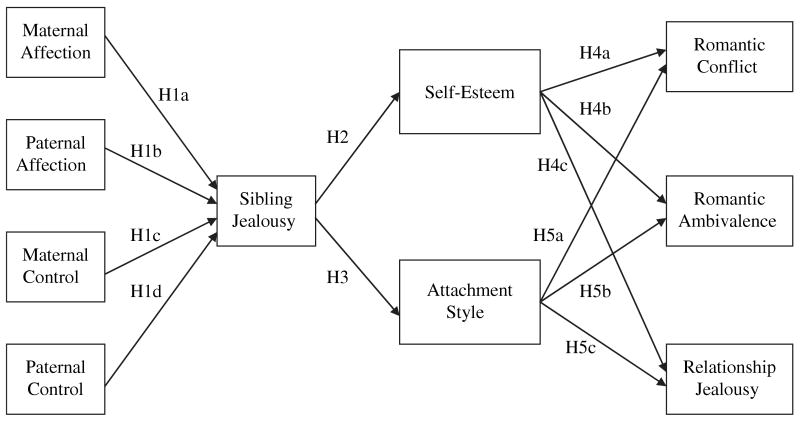

Utilizing both attachment theory and research regarding self-esteem, the current study seeks to address this gap by testing the hypothesis that the early nonshared environment may affect later romantic relationship distress through affective (self-esteem) and cognitive (attachment style) pathways. Toward this end, the remainder of this introduction is organized into three sections. The first offers a brief review of the literature on how individuals internalize experiences in the early family environment. The second examines how these early experiences within the family come to be associated with romantic relationship distress through these internalized models. The final section provides an overview of the current study, which draws upon a survey of young adults to evaluate the proposed model between the early nonshared environment and romantic relationship distress (see Figure 1). The current study focuses on the developmental period of early adulthood because of its significance in the formation of romantic relationships (W. A. Collins, 2003; Erikson, 1968).

Figure 1.

Proposed model of the pathways from early family experience to romantic relationship distress in young adulthood.

Internalization of the early familial environment

Developmental theories have long underscored the importance of early childhood experiences for the development of romantic relationships in adulthood (Freud, 1905/1962), but it has only been within the past two decades that researchers have identified the mechanisms through which the early family environment influences adult romantic relationships. Research on both attachment theory and self-esteem suggest that individuals internalize early experiences within the family and that these internal models inform the individual both of their own value and the value of being in a close, interpersonal relationship (W. A. Collins & Sroufe, 1999; Crocker & Park, 2004; Hazan & Shaver, 1987; Steinberg, Davila, & Fincham, 2006).

Internalization of early family experiences

Attachment theory proposes that models of self and others are a result of early childrearing histories, in particular experiences in the caregiver–child relationship (Bowlby, 1969–1973). These internal working models of attachment are extremely influential for adult romantic relationship development (Hazan & Shaver, 1987), whereby “individuals enter new relationships with a history of interpersonal experiences and a unique set of memories, beliefs, and expectations that guide how they interact with others and how they construe their social world” (N. L. Collins, Cooper, Albino, & Allard, 2002, p. 966). Researchers often classify these attachment styles based on how positively or negatively the individuals view themselves and others. For example, Bartholomew and Horowitz (1991) delineated four attachment styles that represent adults' views of themselves and others: secure, dismissing, preoccupied, and fearful. In their framework, secure individuals had positive models of both self and other; dismissing individuals viewed the self positively, and viewed others negatively, preoccupied individuals viewed the self negatively and viewed others positively, and fearful individuals had negative working models of both the self and others.

Also suggesting that early adult models of self and others are constructed through early childhood experiences is Crocker's recent research on contingencies of self-worth and self-esteem (Crocker & Park, 2004; Park, Crocker, & Mickelson, 2004). According to Crocker and Park, self-esteem is constructed throughout childhood and into adulthood, and begins with the children's emotional experiences with caregivers. Potentially threatening or frightening experiences in caregiver–child relationships (e.g., fear of abandonment, rejection) may mean the child forms mental models of others (e.g., cannot be counted on in times of stress) and whether they are worthy of love and care (i.e., a sense of self-worth). Crocker and Park suggest that the domains in which people choose to invest their self-worth are not necessarily those in which they are successful but rather they are the domains in which if they did succeed, it would make them feel safe and protected from the perceived threats of their childhood. Contingencies of self-worth (CSWs), then, are those affective domains that an individual seeks to satisfy in an effort to feel worthy and, in turn, safe and secure. Not surprisingly, family support is a central CSW for self-worth and reflects the self-esteem one derives from the love, support, and protection offered by family members.

Internalization of early nonshared experiences

The early caregiving environment is seen as crucial for the development of internal models of self and others in both attachment theory and the work on self-esteem, yet Sheehan and Noller (2002) recently argued that it is the within-family differences in parental differential treatment (PDT) in comparison to between-family differences that explain individual differences in working models of self and others. They suggested it is the continued experience of differential parenting that adversely affects the individual's internal model, with the disfavored sibling developing more negative expectations about the availability and sensitivity of others than the favored sibling. Further, Sheehan and Noller found that experiencing greater parental control and less affection in comparison to their sibling led to disfavored siblings having lower self-esteem. Consistent with this finding, Zervas and Sherman (1994) found that young adults who reported being disfavored had lower self-esteem than did the no-favoritism (meaning equal treatment) individuals, and lower self-esteem regarding their family relationships than either the favored or the equal-treatment participants. They also found that participants who reported equal treatment had higher self-esteem regarding their social skills and interactions with their peers than even the favored individuals.

Given that children are aware of the behaviors a parent directs toward their sibling from an early age (Dunn & Kendrick, 1982), it is clear that we must expand our focus regarding the internalization of early family experiences to include how individuals' models of self and others are influenced by their experiences of the early nonshared environment. In light of this, we propose that being the recipient of less parental affection and greater control in comparison to one's sibling may engender negative views not only of the self but also of others (Sheehan & Noller, 2002; Zervas & Sherman, 1994). These negative models are likely to manifest themselves both cognitively and affectively, such that disfavored individuals not only think about relationships differently than do favored individuals but also feel unloved and suffer low self-esteem as a result. It should be noted that although mothers' and fathers' differential treatment of their children have been shown to be moderately related (Volling, 1997; Volling & Belsky, 1992), McHale, Crouter, McGuire, and Updegraff (1995) found that many parents reported incongruent differential treatment patterns (e.g., mother reports favoring the younger sibling and father reports equal treatment). This suggests that mothers' and fathers' differential treatment may be differentially associated with developmental outcomes and should be treated as separate processes in the current study as they relate to individuals' models of self and others.

The role of sibling jealousy

Although these studies assume that PDT is directly associated with adjustment and cognitive and affective internal models, recent research has found that siblings' perceptions of differential parenting were more consistently associated with well-being than was the actual PDT itself (Kowal, Kramer, Krull, & Crick, 2002; McHale, Updegraff, Jackson-Newsom, Tucker, & Crouter, 2000). Even when parents work hard to treat their children equally, negative implications can still emerge if the children perceive the treatment to be unequal. A likely consequence of this perceived unfairness in treatment by parents is sibling jealousy (G. H. Brody, 1998). Jealousy is defined here as an organized complex of emotions, cognitions, and behaviors that result from a threat to or loss of a beloved relationship to a rival (Volling, McElwain, & Miller, 2002). With regard to the sibling relationship, the beloved is one's parent and the rival in question is one's own sibling. Jealousy in the sibling relationship has often been viewed as the product of differential parenting (G. H. Brody, 1998), whereby one child receives preferential treatment compared to another less favored child. The present study hypothesizes that experiencing less maternal affection (H1a) and paternal affection (H1b), as well as greater maternal control (H1c) and paternal control (H1d), will be associated with an individual reporting greater feelings of jealousy toward one's sibling.

Given that Sharpsteen and colleagues (Sharpsteen, 1995; Sharpsteen & Kirkpatrick, 1997) have argued that attachment processes are activated in jealousy-provoking situations, sibling jealousy in particular may provide a window into an individual's working model of attachment. Utilizing N. L. Collins et al.'s (2002) understanding of attachment styles as being constructed based on a history of interpersonal experiences is suggestive of why siblings would be a relevant other for most individuals. In families with multiple children (80% of families in the United States, where we conducted the current study), the sibling represents one of the first others that an individual will have continued experience with, thereby making it likely that the individual will evaluate themselves and their own treatment based on comparisons with their sibling's treatment. Individuals who perceive themselves to be less favored than their sibling should be more likely to develop an insecure view of themselves in comparison to individuals who perceive themselves as worthy of affection and love in comparison to their sibling. Further, individuals who are jealous of their sibling may see others as competitors and potential enemies rather than sources of support and as a result focus more on the self and less on others in an effort to maintain their self-esteem (see Crocker & Park, 2004). Together, these findings suggest that the continued experience of PDT will be associated with an individual's internal affective and cognitive models through its effects on sibling jealousy, such that individuals who report experiencing more sibling jealousy will report lower self-esteem (H2) and be classified as insecurely attached (H3).

How these early experiences influence romantic relationship distress in early adulthood

How do early experiences of the family environment come to be associated with romantic relationship outcomes in young adulthood? The current study proposes that the cognitive and affective models that are engendered by the early nonshared environment offer two separate but related pathways between the early familial environment and young adult romantic relationships. The relationship between these two pathways is illustrated by work showing that individuals with different attachment styles invest their self-esteem in different CSWs. Park et al. (2004) found that secure individuals were more likely to base their self-esteem on family support than were fearful and dismissing individuals. On the other hand, individuals with preoccupied attachments were more likely, and dismissing individuals the least likely, to seek self-esteem based on other's approval. Although this research reveals the close ties between attachment and self-esteem, attachment styles reflect a cognitive model that guides how individuals evaluate and react to new relationships (N. L. Collins et al., 2002), whereas self-esteem reflects an emotional, affective evaluation of oneself as either good or bad. Both offer potential mechanisms through which the early environment influences romantic relationship distress in young adulthood.

In general, individuals with negative internal models have greater difficulty establishing loving, trusting relationships as young adults (Guerrero, 1998; Volling, Notaro, & Larsen, 1998). Regarding the cognitive pathway, a substantial body of research has documented differences in romantic relationship outcomes as a function of attachment styles. Secure attachments are associated with less romantic relationship distress than are preoccupied, fearful, and dismissing attachment styles (e.g., Bartholomew, 1990; Feeney & Noller, 1990; Pistole, 1989; Volling et al., 1998). With regard to the affective pathway, research demonstrates that individuals' self-esteem is strongly associated with their experiences in romantic relationships, such that individuals who feel badly about themselves and their own value as a romantic partner have greater difficulty establishing happy, healthy romantic relationships. For example, Buunk (1997) found self-esteem to be inversely related to jealousy in romantic relationships. Similarly, self-esteem was found to be inversely associated with engaging in more negative conflict behaviors in young adult romantic relationships (Gurung, Sarason, & Sarason, 1997). Therefore, we test the hypothesis that having lower self-esteem and being insecurely attached will be associated with the experience of more romantic conflict (H4a, H5a), more ambivalence (H4b, H5b), and more romantic jealousy (H4c, H5c).

The current study

When considered together, these disparate bodies of research indicate that experiences with the early nonshared environment may result in differing levels of self-esteem and attachment security between siblings within the same family, and these internal models may in turn be related to romantic relationship distress in young adulthood. Given that the role of the early nonshared environment in later romantic relationship distress has not been examined to date, the goal of the current study was to examine if and how early experiences with the nonshared environment come to be associated with romantic relationship distress. We chose to examine young adults because developmental theories posit that the period between the ages of 18 and 25 is characterized by profound role changes (Arnett, 2000; Chen et al., 2006). One of the most important changes for young adults is renegotiating their role in the family of origin as an independent adult in order to establish and maintain relationships with friends and romantic partners. Therefore, studying individuals at this age should allow a unique window into how early family experiences are associated with later romantic relationship distress.

Toward this end, the present study examined three dimensions of relationship distress that the literature has identified as contributing to lower quality romantic relationships: conflict, jealousy, and ambivalence. W. A. Collins (2003) identified distressed young adult romantic relationships as being characterized by notably high levels of conflict. Researchers have also found that many young adults struggle with feelings of jealousy in their early romantic relationships (Larson, Clore, & Wood, 1999), and work with premarital couples indicated that relationship distress arose for those individuals who were ambivalent regarding continuing on their current relationship (Kelley, Huston, & Cate, 1985).

To date, research has identified several additional factors that are likely to influence romantic relationship distress. Age is one potential covariate in that older individuals may have more serious romantic relationships and, as a result, may experience more serious conflict and greater feelings of jealousy at the real or perceived loss of their romantic relationship (W. A. Collins, 2003). Cramer (2000) also found that the frequency of conflict was positively associated with romantic relationship duration in young adulthood. Finally, Buunk (1997) found that birth order was associated with romantic distress, such that later-born children experienced greater jealousy than did firstborn children. The current study will examine age, birth order, and the duration of one's romantic relationship as potential covariates that might explain the links between the nonshared environment and romantic relationship distress.

Method

Participants

Our goal was to examine young adults who experienced varying levels of relationship distress in their dating relationships. We therefore recruited participants from an introductory developmental psychology course at a large, competitive state university in the Midwestern region of the United States. Utilizing this sample takes advantage of the diverse population of young adults found in this particular campus setting, while keeping the cost of conducting the research within reason. The sample consisted of 200 young adults, composed of 152 (76%) females and 48 (24%) males who ranged in age from 18 to 22 (M = 20.25, SD = .92). The ethnic distribution of the sample was 79.5% Caucasian, 5.5% Asian American, 4.5% African American, 4.5% Latino, and 6% other. We collected data on 273 individuals but excluded 73 participants from the analyses: 21 only children, 4 married individuals, 44 individuals who had never had a romantic relationship, and 6 with same-sex partners. Of the remaining 200 participants, 59.5% were currently involved in a romantic relationship and 40.5% had previously been involved in a romantic relationship.

With regard to sibling characteristics, 50% of the sample had one sibling, 28% had two siblings, and 22% had three or more siblings. Further, 43% of the sample was firstborns, 40% was second borns, and 17% was third or later borns. For the measures of PDT, we instructed the participants to compare themselves with their closest age sibling: 51.5% of the sample reported on their older sibling, whereas 48.5% answered regarding their younger sibling. Further, 54.5% reported with respect to brothers and 45.5% with respect to sisters. There were 40.5% female participant and brother dyads, 35.5% female participant and sister dyads, 13.5% male participant and brother dyads, and 10.5% male participant and sister dyads. Finally, 92.5% of the sample reported on a full biological sibling, 4.5% reported on a half-sibling, and 2% reported on a stepsibling.

Procedures

The researchers informed the participants at the end of a developmental psychology class that they had the opportunity to participate voluntarily in a study for course credit regarding early family experiences and current romantic relationship adjustment. Questionnaires included a cover sheet that indicated that in completing the questionnaire, the participant was giving consent.

Measures

Differential parenting

The four differential parental treatment subscales of the Sibling Inventory of Differential Experience (SIDE; Daniels & Plomin, 1985) assessed experiences of differential parenting. Participants rated how much of the particular behavior they experienced relative to their closest age sibling during childhood on a 5-point Likert scale, with lower scores reflecting that the sibling received more of the parental behavior in comparison to the participant and higher scores reflecting that the participant received more of the parental behavior in comparison to their sibling (1 = toward the sibling much more than me; 3 = same; 5 = toward me much more than the sibling). The questionnaire consists of four subscales that assessed separately feelings of differential affection (five items) from the mother and the father (e.g., “Was proud of the things we did”) and differential control (four items) from the mother and the father (e.g., “Was strict with us”). We assessed the inter-item reliability using Cronbach's alphas, which ranged from .69 to .78.

Sibling jealousy

The six-item sibling jealousy subscale of the SIDE (Daniels & Plomin, 1985) assessed participants' experiences of sibling jealousy in childhood. Participants evaluated jealousy with respect to their closest age sibling on a 5-point scale (1 = sibling much more; 3 = equally jealous; 5 = me much more) whether they had been more that way, their sibling was more that way, or both were equally that way (e.g., “In general, who was more likely to get jealous of the other?”; α = .82).

Self-esteem

Participants completed the 10-item Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1979). Participants rated on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly agree to 5 = strongly disagree) how much they agreed with general feelings about themselves (e.g., “All in all, I am inclined to feel that I am a failure”; α = .90).

Models of attachment

Participants completed the forced-choice Relationship Questionnaire (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991). Individuals chose one of the following four vignettes regarding their attachment style with reference to their romantic relationships: secure (“It is easy for me to become emotionally close to others. I am comfortable depending on others and having others depend on me. I don't worry about being alone or having others not accept me.”; 53% of sample), dismissing (“I am comfortable without close emotional relationships. It is very important to me to feel independent and self-sufficient, and I prefer not to depend on others or have others depend on me.”; 12%), preoccupied (“I want to be completely emotionally intimate with others, but I often find that others are reluctant to get as close as I would like. I am uncomfortable being without close relationships, but sometimes worry that others don't value me as much as I value them.”; 16%), or fearful (“I am uncomfortable getting close to others. I want emotionally close relationships, but I find it difficult to trust others completely, or to depend on them. I worry that I will be hurt if I allow myself to become too close to others.”; 19%).

Hazan and Shaver (1987) have found forced-choice measures to be both reliable and valid, such that respondents who chose the forced-choice descriptions differed in predicted ways in their romantic experiences, self-perceptions, and childhood experiences. Further, Cassidy (2003) noted that the continuous model of individual differences explained almost virtually identical amounts of variance as did the categorical model in Fraley and Spieker's (2003) article on categorical versus continuous models of attachment patterns, suggesting that both assessments are valid. In addition, the categorical approach eliminates the possibility that individuals would rate themselves as being similar to multiple vignettes (e.g., they could be classified equally well as either securely attached or having a dismissing attachment). Utilizing the forced-choice measure ensures that the individuals choose the attachment classification that they believe is most representative of how they approach their intimate relationships. Finally, given the extremely high correlations between romantic jealousy and the attachment anxiety scale (r = .80–.85; Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, 1998), we chose to use the categorical attachment measure.

Romantic relationship distress

Participants completed the 25-item Braiker and Kelley (1979) Intimate Relations Scale to assess distress in their current relationship. Individuals rated on a 9-point scale the degree to which each statement was characteristic of their romantic relationship with their partner (1 = very little or not at all to 9 = extremely or very much). The questionnaire consists of four subscales: love, maintenance, conflict, and ambivalence. Given our interest in romantic relationship distress, we chose to examine only the five-item conflict scale (e.g., “How often do you and your partner argue with one another?”; α = .76) and the five-item ambivalence scale (e.g., “How confused are you about your feelings toward your partner?”; α = .79). Participants also completed the six-item Relationship Jealousy Scales (White, 1981) to assess romantic jealousy in their current or most recent romantic relationship. Individuals rated on a 5-point scale (1 = not very much to 5 = very much) the degree to which the item pertained to their romantic relationship (e.g., “How much is your jealousy a problem in your relationship with your partner?”; α = .88).

Results

Analysis plan

The results are presented in three sections. First, descriptive and preliminary analyses were conducted. Second, we examined the affective model linking differential parenting to current romantic relationship distress through its effects on sibling jealousy and self-esteem. Third, we analyzed the cognitive model by examining the paths between differential parenting, sibling jealousy, attachment style (i.e., working models of self and others), and current romantic relationship distress.

Because there were more females than males in our sample (152 women and 48 men), we examined whether results differed by gender using multigroup structural equation modeling for the affective pathway. To test whether the proposed links predicting relationship distress on the basis of self-esteem differed as a function of gender, we compared two path models, one with free parameters and one with parameters fixed across groups (Muthén & Muthén, 2004). A chi-square difference test revealed that the path model in which the parameters were allowed to vary freely was not significantly different from the path model in which the parameters were constrained to be equal, χ2(9 df) = 13.78, p > .10, indicating that men and women could be considered as a single population in the present analyses. Further, we found no significant main effects of gender or Gender × Attachment interactions for the model predicting relationship distress on the basis of attachment status. Therefore, the more parsimonious single-group analysis of 200 individuals was chosen for the presentation of the following results.

Descriptive statistics and preliminary analyses

Tables 1 and 2 show the means and standard deviations for the study variables and the correlations among them. The preliminary analyses examined the variables central to the analysis and their associations with the following potential covariates: age, relationship duration, and birth order. In addition, we examined whether or not the participant was reporting on a current or past relationship, and if it was a past relationship, how long ago was the previous relationship. Only birth order and relationship duration showed significant associations with the variables of interest. Later-born siblings were more likely to report conflict in their romantic relationships, r = .14, p < .05, than firstborn siblings. In addition, romantic relationship duration was associated with reports of romantic conflict, r = .31, p < .01. There were no statistical differences for any of the variables of interest based on whether the participant was reporting on a current or past relationship (e.g., all ps > .05). We therefore collapsed the current versus past relationship groups and ran analyses on the full sample. We ran subsequent analyses controlling for birth order and romantic relationship duration.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

| Measures | M | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parental differential treatment | |||

| Maternal affection | 3.05 | 0.43 | 1.8–5 |

| Paternal affection | 3.08 | 0.49 | 1.4–5 |

| Maternal control | 3.10 | 0.63 | 1.25–5 |

| Paternal control | 2.94 | 0.67 | 1–5 |

| Sibling jealousy | 3.00 | 0.78 | 1.33–4.67 |

| Self-esteem | 3.50 | 0.71 | 1.25–4.50 |

| Romantic relationship distress | |||

| Conflict | 4.30 | 1.38 | 1–9 |

| Ambivalence | 4.31 | 1.15 | 1.40–7.60 |

| Relationship jealousy | 2.32 | 0.86 | 1–5 |

| Relationship duration (in months) | 7.38 | 5.52 | 1–24 |

Table 2. Partial correlations between romantic relationship quality, self-esteem, and differential parenting.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Romantic conflict | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 2. Romantic ambivalence | .23** | 1.0 | |||||||

| 3. Romantic jealousy | .25** | −.11 | 1.0 | ||||||

| 4. Sibling jealousy | .15* | −.05 | .06 | 1.0 | |||||

| 5. Self-esteem | −.25** | −.11 | −.20** | −.26** | 1.0 | ||||

| 6. Maternal affection | −.08 | .05 | −.06 | −.25** | .16* | 1.0 | |||

| 7. Paternal affection | −.10 | .07 | −.07 | −.21** | .07 | −.29** | 1.0 | ||

| 8. Maternal control | .07 | .00 | .07 | .02 | −.11 | −.27** | .07 | 1.0 | |

| 9. Paternal control | .17* | −.03 | .22** | .05 | −.11 | −.05 | −.23** | .32** | 1.0 |

Note. Controlling for birth order and relationship length.

p < .05.

p < .01.

The affective pathway

We predicted that PDT would be linked to sibling jealousy (H1a to d) and that sibling jealousy would be associated with self-esteem (H2). We, in turn predicted that self-esteem was associated with romantic relationship distress (H4a to c). We tested these predictions using path analysis in Mplus Version 3.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 2004), with the four indicators of differential parenting as exogenous variables; the variables of sibling jealousy, self-esteem, and the three indicators of romantic relationship distress as endogenous variables; and birth order and romantic relationship duration as controls. We tested two models to determine whether PDT was indirectly associated with romantic relationship distress through its effects on sibling jealousy and self-esteem or if PDT was directly associated with sibling jealousy, self-esteem, and romantic relationship distress. We evaluated goodness of model fit for both the indirect effects and the direct effects models using the chi-square statistic (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1984), the comparative fit index (CFI; Bentler, 1990), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; Bentler, 1995).

The overall chi-square goodness of fit test for the indirect effects model yielded a non-signficant chi-square value, χ2(19 df) = 20.19, p > .10, signifying the fit of the model to the data. We confirmed the goodness of fit with both the CFI and the RMSEA (CFI = .987, RMSEA = .018). A chi-square difference test between the nested indirect effects model and the direct effects model was nonsignificant, χ2(16 df) = 16.98, p > .10, indicating that a model that required Mplus to mediate all effects on romantic relationship distress fit as well as a model that included direct paths between PDT and the endogenous variables. Given that the models did not significantly differ, we considered the more parsimonious model (the indirect effects model) to better capture the relations among the constructs (Fincham, Paleari, & Regalia, 2002). The resulting indirect effects model and the path coefficients are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Final model of the affective pathway from early family experience to romantic relationship distress in young adulthood.

Note. Significant paths between variables are represented with bold lines. Nonsignificant paths are represented with dashed lines.

As predicted, parental differential affection was significantly related to sibling jealousy, such that increases in maternal and paternal affection were associated with decreases in jealousy of one's sibling. Contrary to our predictions, however, neither maternal nor paternal differential control was related to sibling jealousy. Consistent with our hypothesis, sibling jealousy was significantly negatively associated with self-esteem, such that increases in sibling jealousy were associated with decreases in self-esteem. Finally, as predicted, decreases in self-esteem were associated with increases in romantic conflict, romantic ambivalence, and relationship jealousy.

The cognitive pathway

Given that the previous analyses demonstrated the paths between parental differential affection and sibling jealousy were significant, we begin with the results for the next set of paths in the sequence. Specifically, we tested whether sibling jealousy would predict working models of attachment and whether these attachment models would, in turn, predict current romantic relationship distress. We conducted multinomial logistic regression analyses to test the association between sibling jealousy and working models of attachment (H3). The overall model of sibling jealousy predicting attachment styles was marginally significant, χ2(3 df) = 6.61, p < .10 (see Table 3). Given Guerrero's (1998) findings that individuals with preoccupied attachment report more jealousy, we used the preoccupied group as a referent group in follow-up analyses, which revealed significant comparisons for the secure and fearful groups and a marginal difference for the dismissing group. The preoccupied group differed from all three other attachment groups on sibling jealousy, such that for every unit increase in sibling jealousy, individuals were 46% less likely to be classified as secure, 47% less likely to be classified as dismissing, and 51% less likely to be classified as fearful than they were to be classified as preoccupied (see Table 3).

Table 3. Multinomial logistic regression analyses predicting attachment status from sibling jealousy.

| Outcome | b | SE | Wald | p | eb | Confidence interval (odds) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secure | −.62 | .27 | 5.32 | .02 | .54 | 0.32–0.91 |

| Dismissing | −.64 | .36 | 3.11 | .08 | .53 | 0.26–1.07 |

| Fearful | −.71 | .32 | 4.88 | .03 | .49 | 0.26–0.92 |

Note. Preoccupied attachment status used as a referent group in the above analyses. eb, odds ratio = the increase in odds of membership for a one-unit increase in the predictor while controlling for the other predictors in the model.

To further investigate the association between sibling jealousy and inner working models of attachment, we conducted a chi-square analysis, χ2(6 df) = 20.49, p < .01, using a three-level variable of sibling jealousy (see Table 4). This variable separated individuals into three groups: a group in which the sibling was more jealous (n = 71), a group in which siblings were equally jealous (n = 70), and a group in which the respondent was more jealous (n = 55). Consistent with the logistic regression analyses, preoccupied individuals reported that they were more jealous than their siblings in childhood. Individuals were more likely to have secure attachments if they reported equal sibling jealousy in childhood, whereas dismissing-avoidant and fearful-avoidant individuals reported their sibling was more jealous than they were.

Table 4. Crosstab results of attachment status by reports of sibling jealousy.

| Sibling jealousy | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Attachment status | Sib more (n = 71) | Equal (n = 70) | Me more (n = 55) |

| Secure (n = 104) | 32 | 49 | 23 |

| Dismissing (n = 23) | 11 | 4 | 8 |

| Preoccupied (n = 32) | 8 | 9 | 15 |

| Fearful (n = 37) | 20 | 8 | 9 |

Finally, to examine the associations between inner-working models of attachment and current romantic relationship distress (H5a to c), we conducted a multivariate analysis of variance with attachment groups as the between-subjects factor, birth order and relationship length as covariates, and romantic conflict, ambivalence, and relationship jealousy as the dependent variables. There was an overall main effect for attachment status on romantic relationship adjustment, F(3,187) = 3.74, p < .01. Using (partial eta squared) as a measure of strength of association, it was found that attachment status accounted for between 4% and 8% of the variability in romantic relationship distress. We found significant univariate main effects for attachment status for all indicators of romantic relationship distress (see Table 5). Both secure and dismissing individuals reported less conflict in their romantic relationships than did either preoccupied or fearful individuals. Secure individuals reported significantly less romantic ambivalence than dismissing or preoccupied individuals. In addition, fearful individuals reported significantly less romantic ambivalence than did dismissing individuals. Finally, secure individuals reported the lowest levels of romantic jealousy compared to the preoccupied or fearful groups.

Table 5. Means (and standard errors) of outcomes as a function of attachment controlling for birth order and relationship duration.

| Attachment status | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Secure (n = 104) |

Dismissing (n = 23) |

Preoccupied (n = 32) |

Fearful (n = 37) |

F(3,190) | ||

| Romantic conflict | 4.07 (0.13)a | 4.07 (0.27)a | 4.78 (0.23)b | 4.76 (0.22)b | 4.17** | .08 | |

| Romantic ambivalence | 4.08 (0.11)a | 4.98 (0.24)c | 4.58 (0.20)b,c | 4.30 (0.19) a,b | 5.14** | .06 | |

| Relationship jealousy | 2.18 (0.08)a | 2.25 (0.17)a,b | 2.58 (0.14)b | 2.53 (0.14)b | 2.79* | .04 | |

Note. Different subscripts indicate significant group comparisons.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

Discussion

The current study explored the developmental correlates of romantic relationship distress in young adulthood using retrospective reports of childhood experiences with parents and siblings. Specifically, we considered the possibility that experiences with differential parenting and sibling jealousy in the family of origin would predispose individuals to stable affective self-evaluations and cognitive attachment styles that would then carry over and affect their romantic relationships in young adulthood. Our findings appeared to support our proposed model of the pathways from early family experiences to current romantic relationship functioning. Parental differential affection from both mothers and fathers, not differential control, was strongly related to feeling jealousy toward one's sibling. Sibling jealousy, in turn, was significantly associated with an individual's affective and cognitive internal models. Finally, these models were consistently related to young adults' romantic relationship distress. These findings are addressed in greater detail below.

Developmental correlates of romantic relationship adjustment in young adulthood

In examining the pathways between childhood experiences and young adult romantic relationships, the results revealed an interesting constellation of characteristics among individuals who reported they received more or less affection from their parents in comparison to their sibling. In line with previous theory, receiving less affection from their mothers and fathers in comparison to one's sibling was associated with greater sibling jealousy (G. H. Brody, 1998). This greater sibling jealousy was associated with lower self-esteem and a preoccupied attachment style. These negative cognitive and affective models were in turn linked to increases in conflict, ambivalence, and jealousy in young adults' romantic relationships.

If being the recipient of less parental affection seems to be detrimental to a sense of self and romantic relationships, what about the individual who is the beneficiary of more affection? Looking only at self-esteem, the results suggest that being the favored child was beneficial as increases in parental affection were associated with increases in self-esteem. Yet, the higher self-esteem did not reflect a more secure attachment style. Instead, these favored individuals who reported that their sibling was more jealous of them endorsed both the dismissing and fearful classifications more than did those individuals who were equally jealous or more jealous of a sibling. The dismissing and fearful classifications were each in their own way associated with poorer romantic relationship adjustment. For dismissing individuals, their romantic relationship profile of less conflict but greater ambivalence suggests that the dismissing individuals' negative model of others was associated with a reluctance to form close, loving relationships in young adulthood. On the other hand, fearful individuals appeared to have stormy, yet committed relationships, in that they reported greater conflict and jealousy but did not report ambivalence about their relationship.

It is worth noting that although there was a direct association between differential paternal control and romantic relationship distress in the correlational analyses, with more differential paternal control positively associated with reports of conflict and romantic jealousy, there were no associations between reports of differential parental control and sibling jealousy. Sheehan and Noller (2002) have suggested that parental differential control, as measured by the SIDE (Daniels & Plomin, 1985), may be unable to differentiate more positive forms of parental control, such as rule formation and monitoring, from more coercive forms of control. Receiving more coercive, punitive parental control is likely to be more closely associated with greater sibling jealousy in comparison to receiving more parental attention in the form of monitoring. Thus, although differential parental control has a direct association with romantic relationship adjustment, it does not appear to be linked via sibling jealousy.

In sum, reporting less parental affection in comparison to one's sibling, but not more parental control, was associated with increases in sibling jealousy, decreases in self-esteem, a greater likelihood of reporting a preoccupied attachment style, and greater romantic relationship distress. On the other hand, reporting more parental affection in comparison to one's sibling, but not less parental control, was associated with decreases in sibling jealousy, increases in self-esteem, but also with increases in reports of romantic relationship distress. Only the individuals who reported that both they and their sibling were equally jealous in childhood had positive internal models, which were associated with better romantic relationship outcomes.

The importance of studying within-family processes

We should take a moment to talk about why individuals reporting that their sibling was more jealous than they were more likely to endorse both the dismissing and fearful descriptions of attachment. Both attachment styles represent a form of avoidance and both have negative models of others, but the dismissing individual has a positive model of the self, whereas the fearful individual has a negative model of self. Although dismissing and fearful individuals have very different models of self, Levy, Blatt, and Shaver (1998) found that both fearful and dismissive individuals perceived their parents as punitive and malevolent.

How do we reconcile these earlier findings with our research reporting that individuals who were the recipients of more parental affection than their siblings were more likely to endorse dismissing and fearful attachments? The vast majority of research to date on attachment relationships, whether in infancy or adulthood, presumes that the only “parenting” that matters in the development of attachments and the consequent internal models of self and others is a result of the direct, one-on-one parenting received from caregivers. But in families with two or more children (approximately 80% of families in the United States), the definition of what constitutes parenting must be broadened to include not only the direct parenting a child receives but also the parenting that is also being received by other children in the family (Feinberg, Neiderhiser, Simmens, Reiss, & Hetherington, 2000). Even toddlers and preschoolers are sensitive to the behavior a parent directs to a sibling (Dunn & Kendrick, 1982) and this attention to parenting “within the family,” not just toward one's self, no doubt continues well into adulthood (Bedford & Volling, 2004). When an individual is the recipient of more love and affection than a sibling, they can still perceive their parent as capable of less love and affection through observing how the parent relates to their brother or sister. Perhaps, they internalize an insecure model reflecting “Yes, I am lovable for now, but my parent is unfair, inconsistent, and rejecting of my sibling. What prevents them from being the same with me at some later point in time?”

These findings present an interesting picture of how within-family socialization processes may come to be associated with very different developmental outcomes, particularly later social outcomes, for two children in the same family. Although we did not have reports from the siblings of our respondents, the findings have implications for understanding how the nonshared family environment can influence children differently. Here we have a case where two children in the same family, one the recipient of more parental affection and the other the recipient of less, may report different levels of childhood jealousy, have higher or lower levels of self-esteem, and identify with very different working models of attachment. Not only does it appear given the findings of the present study that siblings who experience differential affection may be more likely to report insecure attachments but they also report different types of insecure attachments that have very different associations with romantic relationship distress, with one preoccupied with relationships and the other potentially dismissing or fearful of close, intimate relationships.

Considered together, the complex associations between PDT and young adults' romantic relationship distress underscore the importance of examining the effects of early experiences within the nonshared environment not only on how individuals feel about themselves but also on how they evaluate and react to new relationships. It is only when looking at the findings from the combined affective and cognitive models that we find support for Zervas and Sherman's (1994) conclusion that individuals who receive equal treatment are better adjusted than individuals who were either favored by their parents or who felt that their sibling was favored. The current study suggests that individuals who grow up in families in which parental affection is perceived to be a contested commodity, even when the individual perceives themselves to be the beneficiary of more affection in comparison to their sibling, may have greater difficulty establishing secure, loving relationships as young adults.

Limitations of the study and considerations for future research

Our confidence in these results is enhanced by our examination of both the affective and the cognitive pathways in our model. This combined model enabled us to understand the whole picture with regard to the processes through which the early nonshared environment comes to be associated with romantic relationship distress in young adulthood. Despite the strength of our combined model, there are several methodological issues in the present study that warrant mentioning. These results are based on retrospective reports of childhood experiences of differential parenting and sibling jealousy. It is unclear whether similar findings would emerge if longitudinal data were available that followed individuals through childhood and into adulthood. Although there are several longitudinal studies examining the prediction of adolescent romantic relationship functioning from childhood indicators of peer relationships (Connolly, Furman, & Konarski, 2000; Furman & Schaffer, 2003; Zimmer-Gembeck, 2002), this is not the case with respect to childhood experiences of sibling jealousy. Given that few developmentalists study jealousy in childhood, there are no studies currently available that can address with longitudinal data the links between childhood sibling jealousy and later romantic relationship development. The links we found here seem encouraging for future longitudinal work to consider the sibling relationship, in particular sibling jealousy, as an important part of the early familial environment.

Although it seems theoretically plausible that childhood indicators of sibling jealousy and differential parenting would precede and predict later relationship functioning as presented in Figure 1, the current data were both correlational and cross-sectional, so we are not in a position to discuss causality or the direction of effects. Although differential parental affection may indeed lead to more sibling jealousy, and in turn, poorer self-esteem and insecure attachments, it is also possible that parents respond to certain characteristics of the child, such as low self-esteem, and this behavior, in turn, gives rise to differential parental affection. In addition, individuals with insecure working models of attachment may misconstrue or exaggerate the differences in parenting or favoritism within their family. It is worth noting that a model testing the reverse causal pathway for the affective pathway, specifically that self-esteem contributed to PDT, did not fit the data, suggesting that the pathways illustrated in Figure 1 were more appropriate in the present study. Again, however, there is a need for longitudinal research to validate the pathways of influence proposed in the current study.

Another possible limitation of the current study was our measurement of sibling jealousy. Because the current study was interested in individuals' differential experiences of childhood jealousy, these analyses cannot speak to the overall amount of jealousy experienced in childhood. For example, both an individual who was minimally jealous and an individual who was extremely jealous would be similarly classified if they reported that they were more jealous than their sibling, regardless of how disparate the jealousy experiences were of the two participants in childhood. Including assessments of overall experienced jealousy in future studies may enable us to understand how the amount of jealousy influences individuals' later social development. In addition, although the current study was interested in young adults' perceptions of PDT and sibling jealousy, future research may want to include reports from both siblings to fully capture how jealous the nonparticipating sibling felt.

Regarding our sample characteristics, the disproportionate number of women to men in our sample may suggest that the findings reported here are more representative of women's experiences in relationships than men's. Although we did not find evidence of different models across gender, we must remain alert to the possibility that different processes may be at work in the development of jealousy for men and women (Pines & Friedman, 1998). In addition, our sample was a convenience sample of young adults in one setting; replications will be necessary to determine whether these findings are generally applicable to all young adults pursuing higher education. Although we speculate that these results would generalize to other young adults' pursuing higher education in other settings (e.g., smaller universities, universities in another country), we are unable to state this definitively without replicating this study in a variety of university contexts.

Finally, although our distribution of attachment styles was in line with previous work (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991; Hazan & Shaver, 1987), the small cell sizes of the insecure attachment styles should be considered as a limitation. The effect sizes for the associations between attachment styles and romantic relationship distress were relatively small, suggesting that our assessment of attachment may not have fully captured the influence of attachment styles on romantic relationship distress in young adulthood.

Despite these caveats, the current research makes a significant contribution to the current literature on the developmental correlates of romantic relationship functioning by extending current understanding of how the early nonshared environment is associated with social development in young adulthood. The findings also provide empirical support for the importance of sibling jealousy as a link between PDT and adjustment, both with respect to individual well-being and romantic relationship functioning. Considering the well-being implications of being in distressed romantic relationships (Beach et al., 2003; Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001), understanding the early precursors to variations in young adult romantic relationship adjustment and the mechanisms through which these occur is crucial.

Given the current government drive to promote the formation and maintenance of high-quality marriages (Karney & Bradbury, 2005), there has been renewed interest in the literature in identifying the early roots of successful functioning in intimate relationships. The present study suggests that within-family variation in parenting and sibling experiences during one's childhood may be a particularly fruitful and important area for understanding how early family experiences affect the quality of romantic relationships in early adulthood. Therefore, efforts to improve the quality of young adults' current and future romantic relationships should focus in part on helping them better understand and potentially resolve lingering negative feelings they may have regarding their early experiences of the family environment. Early experiences in the family lay the foundation for subsequent social and emotional development in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood, and growing up in family environments characterized by differential treatment, regardless of who the beneficiary is, may undermine individuals' sense of security and self-worth and consequently their functioning in later romantic relationships.

Acknowledgments

This Child Health and Human Development paper was written while the first author was supported by a predoctoral fellowship from the National Institute of Development (NICHD) Developmental Training Grant awarded to the University of Michigan (T32 HD007109). The second author was supported by an Independent Scientist Award (K02 HD047423) from NICHD. The authors wish to thank Justin Jager and Laura Klem for their invaluable assistance with statistical analyses. Portions of this work were presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research on Child Development (Atlanta, April 2005).

References

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55:469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker L, Daniels D. Nonshared environmental influences and personality differences in adult twins. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58:103–110. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.58.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew K. Avoidance of intimacy: An attachment perspective. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1990;7:147–178. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew K, Horowitz LM. Attachment styles among young adults: A test of the four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:226–244. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach SRH, Katz J, Kim S, Brody GH. Prospective effects of marital satisfaction on depressive symptoms in established marriages: A dyadic model. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2003;20:355–371. [Google Scholar]

- Bedford VH, Volling BL. A dynamic ecological systems perspective on emotion regulation within the sibling relationship context. In: Lang FR, Fingerman KL, editors. Growing together: Personal relationships across the lifespan. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2004. pp. 76–102. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. EQS structural equations program manual, multivariate software. Encino, CA: Multivariate Software; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Black KA, Schutte ED. Recollections of being loved: Implications of childhood experiences with parents for young adults' romantic relationships. Journal of Family Issues. 2006;27:1459–1480. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss. 1–2. New York: Basic Books; 1969–1973. [Google Scholar]

- Braiker H, Kelley HH. Conflict in the development of close relationships. In: Burgess RL, Huston TL, editors. Social exchange in developing relationships. New York: Academic Press; 1979. pp. 135–168. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan KA, Clark CL, Shaver PR. Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In: Simpson JA, Rholes WS, editors. Attachment theory and close relationships. New York: Guilford; 1998. pp. 46–76. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH. Sibling relationship quality: Its causes and consequences. Annual Review of Psychology. 1998;49:1–24. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody LR, Copeland AP, Sutton LS, Richardson DR, Guyer M. Mommy and daddy like you best: Perceived family favoritism in relation to affect, adjustment and family process. Journal of Family Therapy. 1998;20:269–291. [Google Scholar]

- Buunk BP. Personality, birth order, and attachment styles as related to various types of jealousy. Personality and Individual Differences. 1997;23:997–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J. Continuity and change in the measure of infant attachment: Comment on Fraley and Spieker. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:409–412. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Cohen P, Kasen S, Johnson JG, Ehrensaft M, Gordon K. Predicting conflict within romantic relationships during the transition to adulthood. Personal Relationships. 2006;13:411–427. [Google Scholar]

- Collins NL, Cooper ML, Albino A, Allard L. Psychosocial vulnerability from adolescence to adulthood: A prospective study of attachment style differences in relationship functioning and partner choice. Journal of Personality. 2002;70:965–1008. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.05029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA. More than myth: The developmental significance of romantic relationships during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2003;13:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Sroufe LA. Capacity for intimate relationships: A developmental construction. In: Furman W, Brown BB, editors. The development of romantic relationships in adolescence Cambridge studies in social and emotional development. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1999. pp. 125–147. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Cui M, Bryant CM, Elder GH. Competence in early adult romantic relationships: A developmental perspective on family influences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:224–237. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly J, Furman W, Konarski R. The role of peers in the emergence of heterosexual romantic relationships in adolescence. Child Development. 2000;71:1395–1408. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer D. Relationship satisfaction and conflict style in romantic relationships. Journal of Psychology. 2000;134:337–341. doi: 10.1080/00223980009600873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Park LE. The costly pursuit of self-esteem. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130:392–414. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels D, Plomin R. Differential experiences of siblings in the same family. Developmental Psychology. 1985;21:747–760. [Google Scholar]

- Donnellan MB, Larsen-Rife D, Conger RD. Personality, family history, and competence in early adult romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:562–576. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn J, Kendrick C. Siblings: Love, envy, and understanding. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Feeney JA, Noller P. Attachment style and romantic love: Relationship dissolution. Australian Journal of Psychology. 1990;44:69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg M, Neiderhiser JM, Simmens S, Reiss D, Hetherington EM. Sibling comparison of differential parental treatment in adolescence: Gender, self-esteem, and emotionality as mediators of the parenting-adjustment association. Child Development. 2000;71:1611–1628. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, Paleari FG, Regalia C. Forgiveness in marriage: The role of relationship quality, attributions, and empathy. Personal Relationships. 2002;9:27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, Spieker SJ. Are infant attachment patterns continuously or categorically distributed? A taxometric analysis of strange situation behavior. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:387–404. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freud S. In: Three essays on the theory of sexuality. Strachey J, translator. New York: Basic Books; 1962. Original work published 1905. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Schaffer L. The role of romantic relationships in adolescent development. In: Florsheim P, editor. Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2003. pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero LK. Attachment-style differences in the experience and expression of romantic jealousy. Personal Relationships. 1998;5:273–291. [Google Scholar]

- Gurung RAR, Sarason BR, Sarason IG. Personal characteristics, relationship quality, and social support perceptions and behavior in young adult romantic relationships. Personal Relationships. 1997;4:319–339. [Google Scholar]

- Hazan C, Shaver P. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52:511–524. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog KC, Sörbom D. LISREL VI: Analysis of linear structural relationships by the method of maximum likelihood. Chicago: National Educational Resources; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Bradbury TN. Contextual influences on marriage: Implications for policy and intervention. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005;14:171–174. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley C, Huston TL, Cate RM. Premarital relationship correlates of the erosion of satisfaction in marriage. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1985;2:167–178. [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Newton TL. Marriage and health: His and hers. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:472–503. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.4.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowal A, Kramer L, Krull JL, Crick NR. Children's perceptions of the fairness of parental preferential treatment and their socioemotional well-being. Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16:297–305. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson RW, Clore GL, Wood GA. The emotions of romantic relationships: Do they wreak havoc on adolescents? In: Furman W, Brown BB, Feiring C, editors. The development of romantic relationships in adolescence. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1999. pp. 19–49. [Google Scholar]

- Levy KN, Blatt SJ, Shaver PR. Attachment styles and parental representations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:407–419. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.5.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Crouter AC, McGuire SA, Updegraff KA. Congruence between mothers' and fathers' differential treatment of siblings: Links with family relations and children's well-being. Child Development. 1995;66:116–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Updegraff KA, Jackson-Newsom J, Tucker CJ, Crouter AC. When does parent's differential treatment have negative implications for siblings? Social Development. 2000;9:149–172. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus users' guide, software. Los Angeles: Authors; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Park LE, Crocker J, Mickelson KD. Attachment styles and contingencies of self-worth. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2004;30:1243–1254. doi: 10.1177/0146167204264000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pines AM, Friedman A. Gender differences in romantic jealousy. Journal of Social Psychology. 1998;138:54–71. doi: 10.1080/00224549809600353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pistole MC. Attachment in adult romantic relationships: Style of conflict resolution and relationship satisfaction. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1989;6:505–512. [Google Scholar]

- Plomin R, Daniels D. Why are children in the same family so different from one another? Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1987;10:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Conceiving the self. New York: Basic Books; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpsteen DJ. The effects of self-esteem threats and relationship threats on the likelihood of romantic jealousy. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1995;12:89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpsteen DJ, Kirkpatrick LA. Romantic jealousy and adult romantic attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;72:627–640. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.72.3.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan G, Noller P. Adolescent's perceptions of differential parenting: Links with attachment style and adolescent adjustment. Personal Relationships. 2002;9:173–190. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg SJ, Davila J, Fincham FD. Adolescent marital expectations and romantic experiences: Associations with perceptions about parental conflict and adolescent attachment security. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35:314–329. [Google Scholar]

- Volling BL. The family correlates of maternal and paternal perceptions of differential treatment in early childhood. Family Relations. 1997;46:227–236. [Google Scholar]

- Volling BL, Belsky J. The contribution of mother-child and father-child relationships to the quality of sibling interaction: A longitudinal study. Child Development. 1992;63:1209–1222. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volling BL, Elins JL. Family relationships and children's emotional adjustment as correlates of maternal and paternal differential treatment: A replication with toddler and preschool siblings. Child Development. 1998;69:1640–1656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volling BL, McElwain NL, Miller AL. Emotion regulation in context: The jealousy complex between young siblings and its relations with child and family characteristics. Child Development. 2002;73:581–600. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volling BL, Notaro PC, Larsen JJ. Adult attachment styles: Relations with emotional well-being, marriage, and parenting. Family Relations. 1998;47:355–367. [Google Scholar]

- White GL. A model of romantic jealousy. Motivation and Emotion. 1981;5:295–310. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh H, Lempers JD. Perceived sibling relationships and adolescent development. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2004;33:133–147. [Google Scholar]

- Zervas L, Sherman M. The relationship between perceived parental favoritism and self-esteem. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 1994;155:25–33. doi: 10.1080/00221325.1994.9914755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer-Gembeck MJ. The development of romantic relationships and adaptations in the system of peer relationships. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31:216–225. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00504-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]