Summary

Integrins are transmembrane heteromeric receptors that mediate interactions between cells and extracellular matrix (ECM). β1, the most abundantly expressed integrin subunit, binds at least 12 α subunits. β1 containing integrins are highly expressed in the glomerulus of the kidney; however their role in glomerular morphogenesis and maintenance of glomerular filtration barrier integrity is poorly understood. To study these questions we selectively deleted β1 integrin in the podocyte by crossing β1flox/flox mice with podocyte specific podocin-cre mice (pod-Cre), which express cre at the time of glomerular capillary formation. We demonstrate that podocyte abnormalities are visualized during glomerulogenesis of the pod-Cre;β1flox/flox mice and proteinuria is present at birth, despite a grossly normal glomerular basement membrane. Following the advent of glomerular filtration there is progressive podocyte loss and the mice develop capillary loop and mesangium degeneration with little evidence of glomerulosclerosis. By three weeks of age the mice develop severe end stage renal failure characterized by both tubulointerstitial and glomerular pathology. Thus, expression of β1 containing integrins by the podocyte is critical for maintaining the structural integrity of the glomerulus.

Keywords: kidney, development, basement membrane, receptors

Introduction

Integrins are heterodimeric transmembrane receptors composed of an α and a β subunit. Integrin β1, the most abundantly expressed subunit, heterodimerizes with at least 12 α subunits, forming dimers which are critical for cellular interactions with extracellular matrix (ECM) components (Hynes, 2002). Integrin α3β1 and α6β1 are major laminin binding receptors, while the predominant collagen receptors are integrins α1β1 and α2β1 (Hynes, 2002). These integrins are highly expressed in multiple organs, including the kidneys, where they are found in both the tubules and glomerulus (Kreidberg and Symons, 2000).

The glomerulus is the principal filtering unit of the kidney and its filtration barrier consists of endothelial cells and podocytes separated by a glomerular basement membrane (GBM) comprised primarily of collagen IV and laminins (Miner, 2005). Both the cellular components and the GBM are required to maintain the integrity of the filtration barrier, and perturbations of any of these components results in developmental or functional aberrations of the glomerulus. The importance of ECM components in glomerular development and integrity has been demonstrated in genetically engineered mice (Cosgrove et al., 1996; Miner and Li, 2000; Miner et al., 1997; Miner and Sanes, 1996; Noakes et al., 1995); however the role of integrins is far less clear.

α3β1 is the only integrin shown to play a significant role in glomerular development in vivo (Kreidberg et al., 1996). Mice lacking the integrin α3 subunit die in the neonatal period and have aberrations in glomerular capillary loops, a disorganized GBM and podocyte foot process abnormalities (Kreidberg et al., 1996). More recently, the integrin α3 subunit was specifically deleted in the podocyte (Sachs et al., 2006). These mice develop massive proteinuria in the first week of life and nephrotic syndrome by 5–6 weeks of age. The kidneys of the 6 week old mice contained sclerosed glomeruli, a disorganized GBM and prominent protein casts in dilated proximal tubules. Electron microscopy revealed complete effacement of podocyte foot processes in newborn mice and widespread lamination and protrusions of the GBM in 6 week-old mice. In contrast to these mice, the total integrin α6-null mice do not have a renal phenotype (Georges-Labouesse et al., 1996), although integrin α6β1 is expressed with its major ligands laminins-111, -511, and -521 (Aumailley et al., 2005) during various stages of glomerular development (Kreidberg and Symons, 2000; Miner, 1999). Furthermore, the total integrin α3/α6 double-deficient mice have a similar glomerular phenotype to that seen in the total α3-null mice (De Arcangelis et al., 1999), suggesting that the α6 subunit is dispensable for glomerular development. Integrins α1β1 and α8β1, both highly expressed in the glomerulus, play a minor role in glomerular development, as both integrin α1- and α8-null mice show subtle glomerular phenotypes characterized by increased glomerular collagen IV deposition and mesangial expansion or mesangial hypercellularity and matrix deposition, respectively (Chen et al., 2004; Haas et al., 2003; Hartner et al., 2002). Glomeruli of integrin α2-null mice do not exhibit any overt glomerular phenotypes (A. Pozzi and R. Zent, unpublished data)

Although integrin α3β1 is the major ECM receptor required for glomerular development, we hypothesized that deleting β1 integrin in podocytes would result in a more profound phenotype than that found in mice lacking theα3 integrin subunit in the podocytes as multiple αβ1 (αsβ1) integrins that interact with the GBM would not be expressed. In this context, ablation of the integrin α3 subunit in the skin only generated microblistering (DiPersio et al., 1997; DiPersio et al., 2000), whereas specific integrin β1 deletion in the epidermis resulted in severe skin blistering, massive failure of BM assembly/organization, hemidesmosome instability, and a failure of keratinocytes within the hair follicles to remodel BM and invaginate into the dermis (Brakebusch et al., 2000; Raghavan et al., 2000). These results suggest that in addition to α3β1, multiple αsβ1 integrins contribute to keratinocyte proliferation/differentiation, ECM assembly and BM formation. In addition, although integrin α3 and α6 subunits are expressed in mammary glands, deleting these subunits in mice did not result in any functional or developmental mammary gland abnormalities (Klinowska et al., 2001). However when β1 was deleted early in mammary gland development the alveoli were disorganized and contained clumps of epithelial cells bulging into what would normally be luminal space (Li et al., 2005; Naylor et al., 2005).

To determine the role of all the αsβ1 integrin heterodimers in glomerular development, we deleted β1 integrin selectively in glomerular podocytes by crossing integrin β1flox/flox mice (Raghavan et al., 2000) with the same podocin-Cre (pod-Cre) mice (Moeller et al., 2003) used to delete the integrin α3 subunit (Sachs et al., 2006). We provide evidence that pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice develop end stage renal failure by 3 to 5 weeks of age due to glomerular abnormalities characterized by podocyte loss followed by degeneration of the glomerulus. Thus, mice in which integrin β1 was deleted from the podocytes have for the most part a similar but worse phenotype than mice where only the α3 integrin subunit was deleted, suggesting that α3β1 is the principal but not the only podocyte integrin required to maintain the glomerular filtration barrier.

Material and Methods

Generation of pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice

All experiments were approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee and are housed in a pathogen free environment. Integrin β1flox/flox mice (generous gift of Dr. E. Fuchs, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, The Rockefeller University) (Raghavan et al., 2000) or integrin β1flox/flox mice, in which a promoterless lacZ reporter gene was introduced after the downstream loxP site (Brakebusch et al., 2000) were crossed with the podocin-Cre mice (pod-Cre) generated as previously described (Moeller et al., 2003). Mice varied between 4th and 6th generation C57BL6. Aged-matched littermates homozygous for the floxed integrin β1 gene, but lacking Cre (β1flox/flox mice), were used as negative controls for pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice. Mice were genotyped by PCR with the following primers: 5′-CGGCTCAAAGCAGAGTGTCAGTC-3′ and 5′-CCACAACTTTCCCAGTTAGCTCTC-3′ for verification of the β1flox/flox (Raghavan et al., 2000); 5′-AGGTGCCCTTCCCTCTAGA-3′ and 5′-GTGAAGTAGGTGAAAGGTAAC for verification of the integrin β1flox/flox mice with the promoter-less lacZ reporter gene (Brakebusch et al., 2000); and 5′-GCATAACCAGTGAAACAGCATTGCTG-3′ and 5′-GGACATGTTCAGGGATCGCCAGGCG-3′ for verification of the podocin cre (Moeller et al., 2003).

Clinical parameters and morphologic analysis

Proteinuria was determined by analyzing 2 μl of urine per mouse on 10% SDS-PAGE gels that were subsequently stained by Coomassie Brilliant Blue.

For morphological and immunohistochemical analysis, kidneys at different stages of development were removed immediately at sacrifice and fixed in 4% formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin, or embedded in OCT compound and stored at −80°C until use, or fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, post-fixed in OsO4, dehydrated in ethanol and embedded in resin. Paraffin tissue sections were stained with either hematoxylin and eosin or Periodic Acid Schiff’s (PAS) for morphological evaluation by light microscopy.

The mesangial cell number was evaluated in a blind fashion by a renal pathologist counting the number of mesangial cells in 100 random glomerular sections per mouse. Glomeruli were counted in 5 individual mice with a total of 500 glomeruli examined in each group. The mesangial cell number was expressed as a mean +/− standard deviation.

For electron microscopy, ultrastructural assessments of thin kidney sections were performed using a Morgagni transmission electron microscope (FEI, Eindhoven, The Netherlands). GBM thickness was assessed by point to point measurements using a 2K × 2K camera (Advanced Microscopy Techniques Corp., Danvers, MA) with the associated digital imaging software. Ten different segments of GBM per mouse from 3 mice were measured and values were expressed as mean +/− standard deviation.

The number of podocytes was determined by counting their number in 10 randomly chosen EM sections of glomeruli with 3 different mice per genotype analyzed. The number of podocytes was expressed as mean +/− standard deviation.

Immunostaining

Rat anti-mouse β1 integrin (MAB1997) was purchased from Chemicon. Rat anti-mouse laminin α1 mAb 8B3 was a gift from Dr. D. Abrahamson (St John et al., 2001) and rabbit anti-human podocin was a gift from Dr. Corinne Antignac (Roselli et al., 2002). Rabbit anti-laminin α5 (Miner et al., 1997), rabbit anti-sera specific for the mouse collagen type IV α4 chain (Miner and Sanes, 1994) and rabbit anti-nephrin (Holzman et al., 1999) have been described. Rabbit anti-chick integrin α3 was a gift from Mike Dipersio, Albany Medical College (DiPersio et al., 1995), CD2AP antibody was a gift from Andrey Shaw (St. Louis, Washington University); and ILK antibody (3862) was purchased from Cell Signaling. Anti-mouse CD31, rabbit polyclonal antibodies to WT1 and anti-VEGF antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Monoclonal antibodies to entactin (clone ELM1 Rat monoclonal) were purchased from Chemicon. Alexa 488- and Cy3- conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR) and Chemicon (Temecula, CA), respectively.

Seven μm kidney frozen sections were incubated with the antibodies described above diluted in PBS with 1% BSA followed by incubation with the appropriate secondary antibody. The sections were subsequently mounted in 90% glycerol containing 0.1X PBS and 1 mg/ml p-phenylenediamine and viewed under epifluorescence with a Nikon Eclipse 800 compound microscope. Images were captured with a Spot 2 cooled color digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI).

Podocyte apoptosis was determined on kidney paraffin sections utilizing Apoptag Apoptosis Detection Kit, as described by the manufacturer (Chemicon). Positive apoptotic cells were counted as podocytes when residing on the outer aspect of PAS-positive basement membrane. Apoptotic cells were determined in 25 random glomeruli per kidney with 4 different mice per genotype analyzed. The number of podocytes was expressed as mean +/− standard deviation.

In situ hybridization

Kidneys were dissected from mice on postnatal day 0, 10 and 21, washed briefly in RNase-free PBS and fixed overnight in DEPC-treated 4% paraformaldehyde. The tissues were then placed in 30% sucrose for 12–24 hours, embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT 4583 compound (Sakura Finetek USA Inc.) and snap frozen. Ten-micron tissue samples were cut on a Leica Jung cryostat (model CM3050; Leica Microsystems Inc.) and transferred to Superfrost microscope slides (Fisher Scientific Co.). The slides were stored at −20°C until needed. Digoxigenin-labeled VEGF-A (kind gift of A. Nagy, Samuel Lunenfeld Research Institute, Toronto, Canada) probes were prepared according to the Roche Molecular Biochemicals protocol (Roche Molecular Biochemicals).

Slides were dried at room temperature for 2 hours, treated with 15ng/ml proteinase K in depc-PBS at 37°C for 5 minutes, washed in depc PBS, fixed in 4% PFA at room temperature for 7 minutes and washed first in depc PBS and then in 2x SSC (PH 7) at room temperature. Slides were prehybridized in mailers for 1 hour at 60°C using hybridization buffer (2.5 ml - 20x SSC, 5 ml formamide, 250 μl – 20% CHAPS, 100 μl – 10% Triton X-100, 50 μl – 10 mg/ml yeast RNA, 25μl – 20 mg/ml Heparin, 100 μl –0.5 EDTA, 0.2 g blocking powder, 1.2 ml depc H2O) after which they were hybridized with the probe (1 ng/ml) diluted in hybridization buffer at 60°’C overnight. The next day the slides were washed sequentially in 0.2XSSC and formamide/0.2x SSC. The slides were blocked with blocking solution from Roche as per instructions and then incubated with anti-DIG antibody for 2 hours. Slides were washed and substrate was added as per instructions from Roche. Slides were washed again and then immersed in Fast Red, dehydrated and mounted.

Statistics

The Student’s t test was used for comparisons between two groups, and analysis of variance using Sigma Stat software was used for statistical differences between multiple groups. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Loss of β1 integrin in the podocyte results in massive proteinuria and end stage renal failure

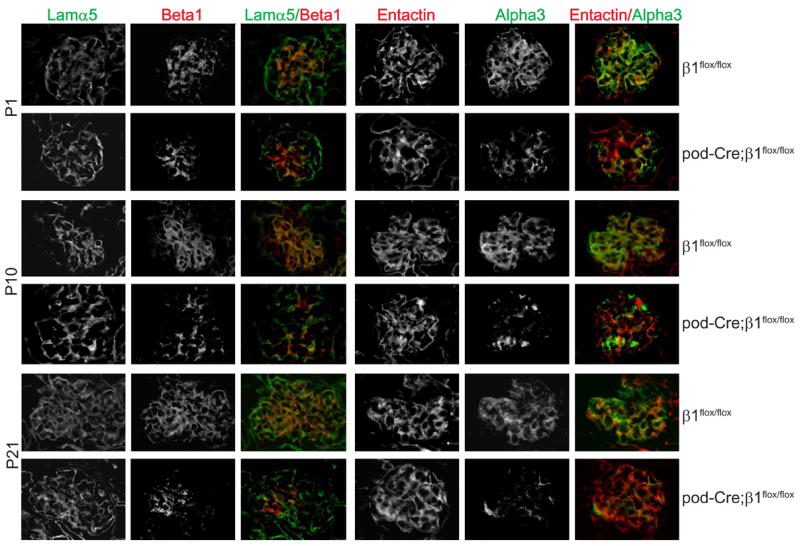

To determine the function of αsβ1 integrins expressed by podocytes in the glomerulus, mice carrying the floxed β1 integrin gene (β1flox/flox) (Raghavan et al., 2000) were crossed with mice expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the podocin promoter (pod-Cre) (Moeller et al., 2003), in which recombination occurs during the capillary loop stage in glomerular development. To verify that the β1 integrin subunit was deleted in the podocytes, we performed immunostaining for the β1 and α3 integrin subunits in P1, P10 and P21 mice. Expression of both of these subunits was significantly reduced in a segmental pattern in P1 pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice (Figure 1) and were further decreased in the glomeruli of P10 and P21 pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice. β1 integrin subunit deletion was verified by crossing pod-cre mice with another floxed β1 integrin mouse, in which a promoterless lacZ reporter gene was introduced after the downstream loxP site (Brakebusch et al., 2000) (data not shown).

Figure 1. β1 integrin subunit is deleted in pod-Cre;β1flox/flox mice.

Frozen sections of kidneys from P1, P10 and P21 β1flox/flox and pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice were co-stained with anti-mouse integrinβ1 (red) and anti laminin-α5 chain (green) or anti-mouse integrinα3 (green) and anti-entactin (red), respectively.

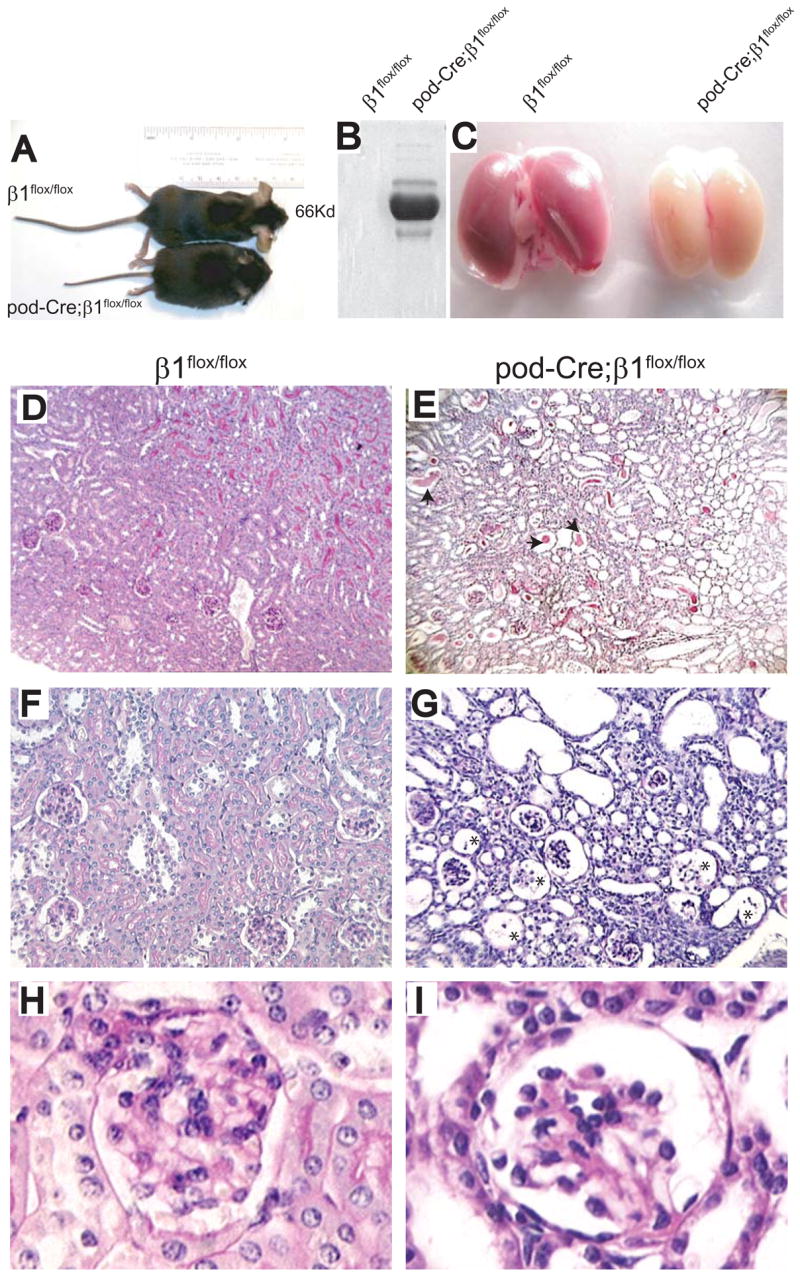

Pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice were born in the expected Mendelian ratio. There were no abnormalities observed in either the β1floxflox or the pod-Cre; β1flox/+ mice over time, however the pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice became less physically active than their littermate β1flox/flox controls and developed severe edema 3 weeks after birth. Ninety percent (18/20) of the pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice were euthanized between 4 and 5 weeks of age due to end stage renal failure and nephrotic syndrome and only 10% (2/20) survived to 6 weeks of age (Figure 2A). The six week old pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice had massive proteinuria, with the predominant band running at the molecular weight of albumin (~ 66Kd) (Figure 2B). Autopsy of the mutant mice revealed smaller and paler kidneys than those isolated from age matched control animals, which are characteristic features of end stage disease (Figure 2C). Numerous Bowmans capsules in pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice were either empty or had partially disintegrated glomeruli as shown in Figures 2G. Interestingly the mesangium was only mildly hypercellular with little matrix expansion (Figure 2I). In addition to the glomerular pathology, there was marked tubular dilatation and flattening of epithelial cells with extensive proteinaceous tubular casts (figure 2E). Thus, all the mutant mice developed end stage kidney disease characterized by pathological changes in the glomeruli and tubulointerstitium.

Figure 2. Six week old pod-Cre;β1flox/flox mice develop severe proteinuria and end stage renal disease.

(A–C) Six week old pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice are smaller with evidence of severe edema (A), albuminuria (2 μl urine/lane) (B) and end stage kidneys (C) compared to aged matched β1flox/flox mice. (D–I) PAS staining of kidneys derived from the mice described above showing glomerular and tubular interstitial abnormalities in the mutant group. The arrows in panel E show dilated tubules filled with hyaline material and the asterisks in panel G show the remnants of glomeruli in the pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice. (D, E = 100 ×; F, G = 200 ×; H, I =630 ×).

Glomerular capillary morphogenesis is normal in embryonic and newborn pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice but becomes abnormal 10 days after birth

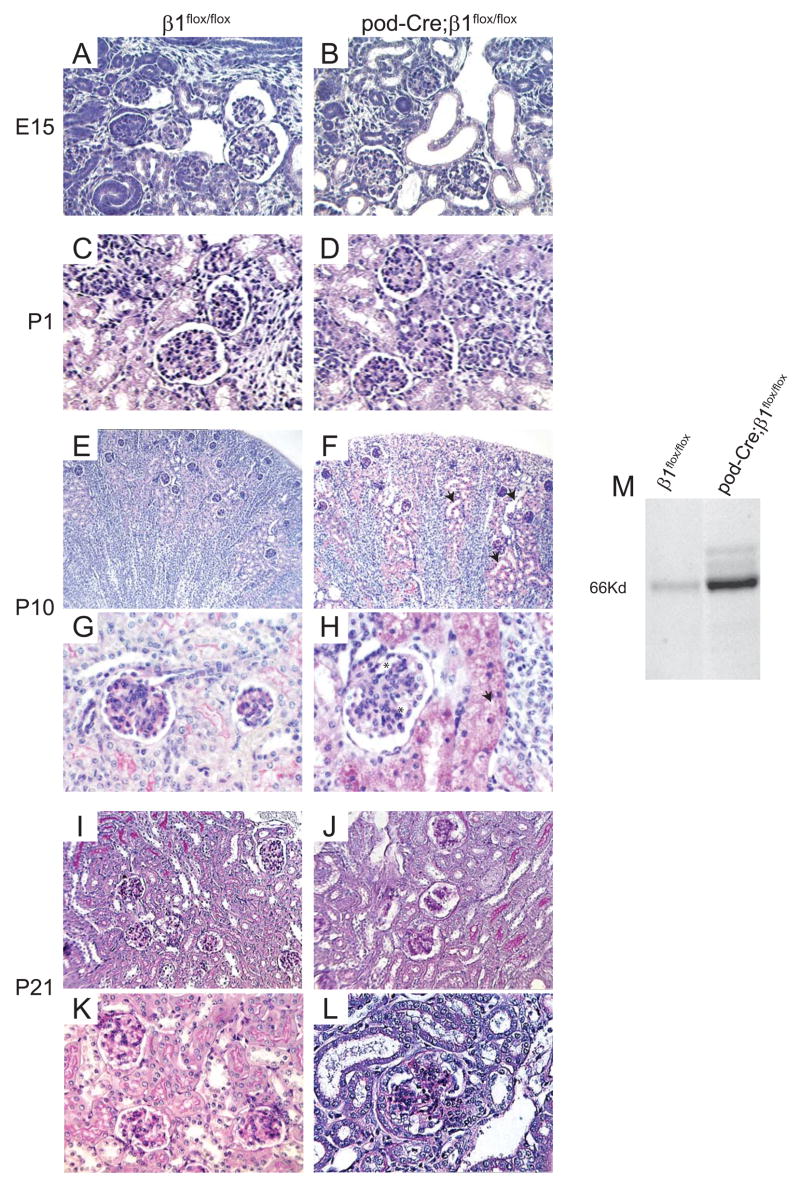

Due to the severity of the renal phenotype in the mutant mice we investigated when the abnormalities first became apparent. The podocin promoter is activated during the capillary formation stage (Moeller et al., 2003), so we initially determined the histology of kidneys derived from E15.5 embryos from 10 wild type and mutant mice. Glomeruli were indistinguishable from the wild type controls in all the pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice when visualized by light microscopy (Figures 3A and 3B). No overt abnormalities were apparent in mutant P1 (n=10) mice (Figures 3C and 3D), however even at this early age the mice exhibited proteinuria (Figure 3M) but no hematuria.

Figure 3. Kidneys from pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice exhibit severe abnormalities in the glomerulus and tubulointerstitium.

(A, B) PAS staining of kidneys derived from E15.5 β1flox/flox and pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice showing no significant differences between the two genotypes (200 ×). (C, D) PAS staining of kidneys derived from newborn β1flox/flox and pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice showing no overall significant differences between the two genotypes (200 ×). (E, F) PAS staining of kidneys derived from P10 β1flox/flox and pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice revealed tubulodilatation (arrow) in the mutant mice (100 ×). (G, H) In P10 mutant mice there was evidence of “ballooned” glomerular capillary loops (asterisk) and protein containing vacuoles (arrow) in the tubules of the pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice (400 ×). (I–L) PAS staining of kidneys derived from 3 week old β1flox/flox and pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice revealed dilated tubules, evidence of “ballooned” capillary loops and mesangial hypercellularity (I, J = 200 ×; K, L= 400 ×). (M) Coomassie staining of urine (2 μl/lane) from newborn β1flox/flox and pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice showing albuminuria in the latter group.

In contrast to controls, kidneys from mutant P10 mice demonstrated tubular dilatation and multiple cytoplasmic vacuoles within the tubular epithelial cells (Figures 3E-H), which are consistent with heavy proteinuria. In addition, some glomeruli from mutant mice showed segmentally “ballooned” capillary lumens (Figures 3H). By 3 weeks of age the tubules showed increased dilatation and there were more “ballooned” capillary loops and mesangial hypercellularity (Figures 3J and 3L). When mesangial cell number was assessed, there were significantly more in the pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice compared to the β1flox/flox mice (17.1 +/− 3.6, vs 11.3 +/− 2.3. p < 0.05).

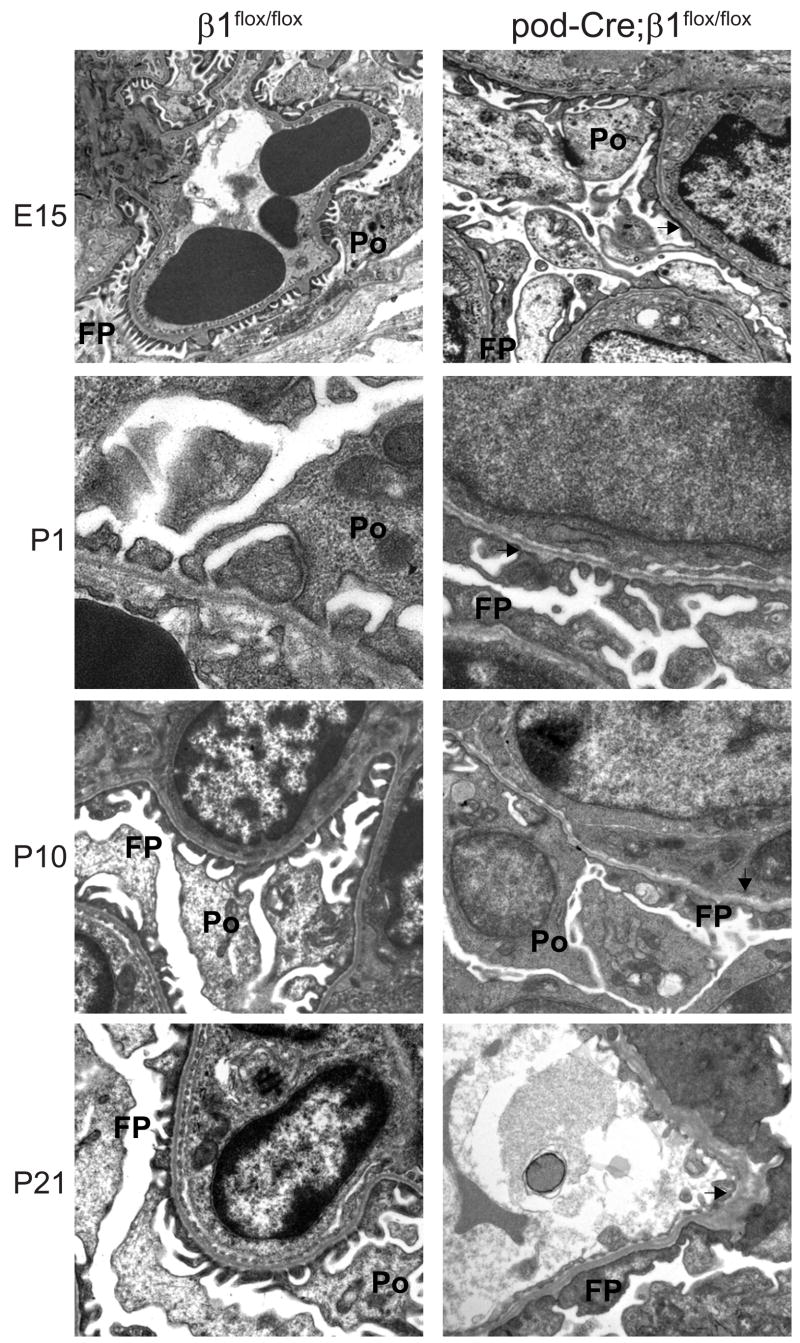

Deletion of β1 integrin in the podocyte results in foot process effacement

To evaluate the integrity of the glomerular filtration barrier, glomeruli of mice at various ages were subjected to examination by electron microscopy. At E15 there was evidence of foot process effacement in the pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice but surprisingly the GBM was intact in both genotypes (Figure 4). Similar ultrastructural findings were present in the kidneys isolated from E17.5 and E19.5 (data not shown) as well as P1 mice (Figure 4). There was no significant difference in thickness of the GBM in β1flox/flox and pod-Cre; β1flox/flox P1 mice (130 +/− 25.9 nm vs. 143 +/− 39.5: p=0.16). Extensive foot process effacement and early segmental splitting of the GBM was observed in P10 pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice and these features became were more evident in the P21 mutant mice (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Glomeruli from pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice demonstrate podocyte foot process effacement.

EM analysis was performed on kidneys of mice at various ages. In the E15 mutant mice there is evidence of foot process effacement of the podocytes but the GBM (arrow) was normal. Similar findings are present in P1 kidneys. In P10 mice, in addition to the foot process effacement, there was evidence of very mild segmental splitting of the GBM (arrow) which progressed by day P21. Abbreviations: FP=Foot Process; Po=Podocyte

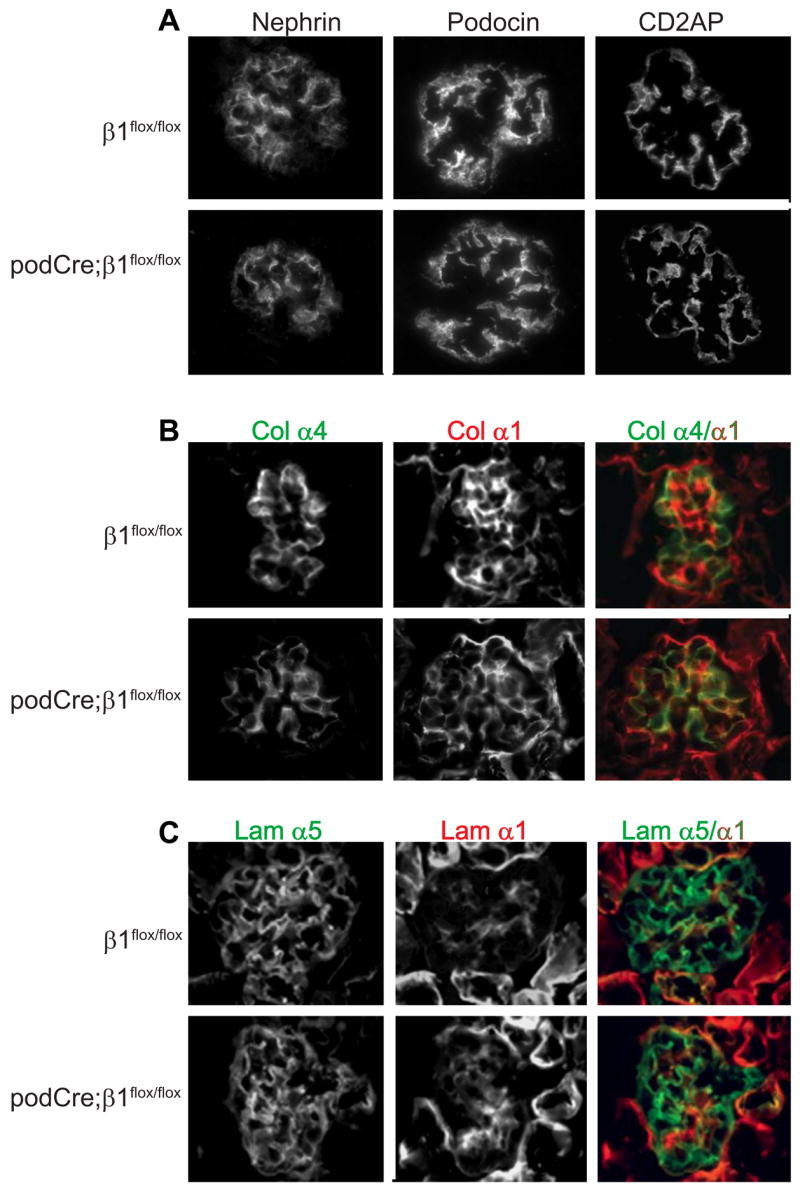

To determine whether the abnormalities in the filtration barrier in newborn mice was due to altered expression or localization of proteins involved in slit diaphragm formation or structural proteins known to be associated with nephrotic syndrome, immunofluorescence was performed for nephrin, podocin, CD2AP (Figure 5A) and synaptopdodin (not shown). Expression and localization of these proteins was similar in control and mutant mice by immunofluorescence. Similar results, with respect to mRNA expression, were found when in situ hybridization assays were performed (data not shown). As integrins are thought to be critical for normal BM development, we examined expression of collagen IV and laminins in glomeruli. Unexpectedly, no differences in collagen IV α1, α3, α4, α5 and α6 chain expression were observed (Figure 5B). Similarly, expression of both laminin α1 and α5 chains as well as α2 and β2 chains (data not shown) was similar in both genotypes (Figure 5C and data not shown). As morphogenesis of the glomerular capillaries appeared to be normal at this stage and no alterations in GBM components were present, we determined whether compensation by overexpression of other receptors for GBM components had occurred. However, once again, no differences in expression of integrin αv, α6 and β4 subunits or dystroglycan were detected in the mutant mice (data not shown).

Figure 5. Glomeruli from newborn pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice demonstrate normal expression of podocyte-specific structural proteins glomerular basement membrane components.

Frozen sections of kidneys derived from newborn mice were stained with antibodies to (A) Nephrin, podocin or CD2AP, (B) the α4 (green) or α1 (red) chains of collagen IV and (C) the α5 (green) orα1 (red) laminin chains.

Taken together these data suggest that during embryogenesis lack of integrin β1 results in podocyte abnormalities characterized by dysmorphic foot processes, with no gross abnormalities in GBM composition or ultrastructure.

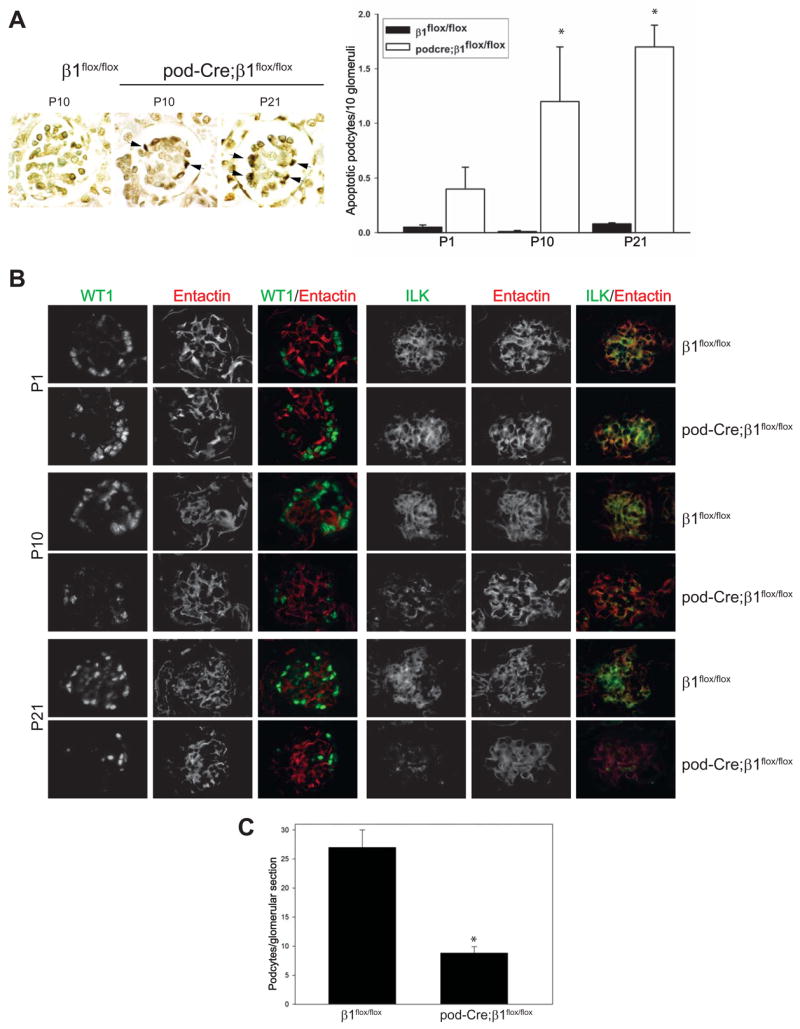

Podocyte apoptosis occurs in pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice within 10 days of birth

Based on the phenotypes of the P21 and 6 week old pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice, where there were dilated glomerular capillaries and subsequent glomerular disintegration, we determined whether the podocytes in the mutant mice were undergoing apoptosis. As seen in Figure 6A, a significant number of apoptotic podocytes were present in the P10 and P21 mutant mice. Furthermore, when expression of the specific podocyte markers WT1 (Figure 6B), podocin, CD2AP and synaptopodin (data not shown) was determined by immunofluoresence, they were significantly decreased in P10 and P21 mutant glomeruli suggesting the possibility of podocyte loss in the pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice.

Figure 6. Podocytes of pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice undergo apoptosis.

(A) Examples of apoptosis, as determined by TUNEL assay, detected in the glomeruli of β1flox/flox or pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice at the time points indicated. The number of apoptotic podocytes expressed per 10 glomeruli is demonstrated graphically. The (*) indicates significant differences (p < 0.01) between the two genotypes. (B) Frozen sections of glomeruli were co-stained for WT-1 (green) and entactin (red) or ILK (green) and entactin (red) as described in the Methods. (C) The number of podocytes in EM sections were evaluated as described in the Methods and expressed as mean +/− SD. (*) indicates significant differences (p < 0.05) between P21 β1flox/flox and P21 pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice.

As deletion of the β1 integrin binding protein, integrin linked kinase (ILK), in podocytes results in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and alteration in the distribution of integrin α3β1 starting at 4 weeks of age (Dai et al., 2006; El-Aouni et al., 2006), we investigated whether deleting the β1 integrin subunit from podocytes altered glomerular ILK expression. As shown in Figure 6B, no differences in glomerular ILK expression were observed in the glomeruli of P1 mutant and control mice. However, by P10 the mutant mice showed a marked decrease in glomerular ILK expression and virtually no ILK was detected in glomeruli by P21. The pattern and time course of ILK expression in the mutant mice was very similar to that seen for β1 integrin (Figure 1), suggesting that expression of the β1 integrin subunit might play a specific role in regulating ILK expression in the podocyte.

To specifically confirm podocyte loss in the P21 pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice, the number of podocytes per glomerular section was determined utilizing electron microscopy. When formally quantified, P21 pod-Cre; β1flox/flox had about one third of the number podocytes compared to their β1flox/flox litter mates (Figure 6C). All together, these data suggest that there are significantly less podocytes in the P21 pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice.

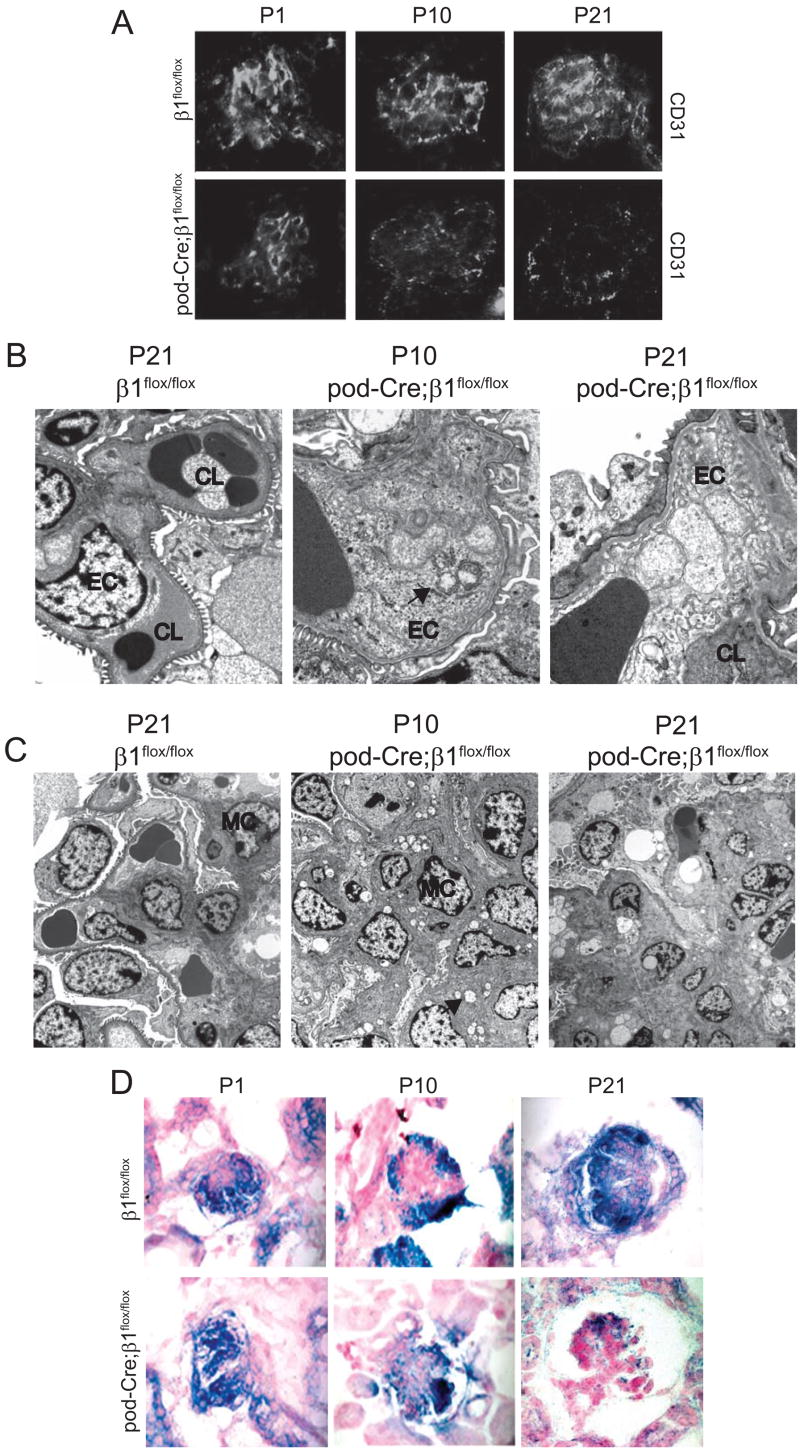

Deletion of β1 integrin in the podocyte results in abnormalities of both capillary loops and the mesangium

One of the most surprising findings of this study was that despite the obvious abnormalities of the podocytes, the principal lesions seen in P21 mutant mice was degeneration of the capillary loops and mesangium with little glomerulosclerosis. To determine the possible mechanism underlying these capillary loop abnormalities, we initially investigated the integrity of the endothelium by staining the kidneys with antibody to CD31, a specific endothelial cell marker. As shown in Figure 7A, the intensity and distribution of CD31 positive cells was similar in P1 β1flox/flox and pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice. By P10 there was significantly less CD31 staining in the glomeruli of mutant mice and by P21 the CD31 staining was virtually undetectable in the mutant mice, suggesting that endothelial cells had undergone cell death during this time period. To verify these findings, electron microscopy was performed on the glomerular capillary loops. The capillary loops in newborn, P10, and P21 β1flox/flox (Figure 7B) as well as newborn pod-Cre; β1flox/flox (data not shown) were normal. However at day 10 significant vacuolation, a sign of cell damage, was present in the endothelial cells of mutant mice (Figure 7B), which was much worse by 3 weeks of age (Figure 7B).

Figure 7. Glomerular capillary and mesangium injury in pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice.

(A) Frozen sections of kidneys derived from newborn, P10 and P21 mice were stained with CD31 antibodies to visualize the glomerular vasculature. (B) EM of kidneys from P21 β1flox/flox (3,000x) as well as P10 (11,000x) and P21 (11,000x) pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice revealed normal morphology of endothelial cells in the β1flox/flox mice. Vacuoles (arrow) in the endothelial cells (arrow) were evident in the P10 and P21 mutant mice. Abbreviations: EC = endothelial cells; CL = capillary loops; (C) EM of kidneys emphasizing the mesangium. Note the presence of vesicles (arrow) in the mesangial cells of mutant mice by P10 (8,900 ×) and the increased mesangial matrix in the P21 pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice (4th panel) (2,200 ×). Abbreviations: MC= mesangial cell. (D) In situ hybridizations on kidneys of newborn, P10 and P21 day old mice showing VEGF mRNA expression.

As mesangial injury was evident in the mutant mice starting at 3 weeks of age (Figure 3), the mesangium was studied in detail by EM. Electron microscopy of the mesangium from newborn, P10, and P21 β1flox/flox (Figure 7C) as well as newborn pod-Cre; β1flox/flox (data not shown) were normal; however there were multiple cytoplasmic vacuoles, indicative of cellular damage, in the mesangial cells of mutant mice starting at 10 days of age (Figure 7C). By 3 weeks there was evidence of increased mesangial matrix with focal defects. These results suggest that the mesangium, like the endothelium, was injured in the mutant mice.

Vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF), which is primarily produced by the podocytes, is a growth factor required for both normal capillary loop development as well as mesangial cell survival (Eremina et al., 2006; Eremina et al., 2003). In this context, mice lacking podocyte-produced VEGF, develop grossly abnormal glomerular capillary loops (Eremina et al., 2003). Furthermore, in mice hypomorphic for podocyte-produced VEGF, there is ballooning of the glomerular capillaries and mesangiolysis (Eremina et al., 2006). This finding suggests that VEGF is required for the normal development and maintenance of glomerular integrity, especially with respect to the capillary loops and the mesangium. As the pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice reduce podocyte number with time, the levels of VEGF were analyzed in the glomeruli of β1flox/flox and pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice. While the mRNA of this growth factor was similar in both genotypes at birth (Figure 7D), decreased mRNA expression was observed in 10 days old mutant mice (Figure 7D) and by 3 weeks significantly less VEGF message was detected in the glomeruli of the pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice (Figure 7D). Thus, the timing of glomerular degeneration correlates with the lack of VEGF expression by the podocytes.

Discussion

β1 integrins are highly expressed in the glomerulus of the kidney (Kreidberg and Symons, 2000); however their role in glomerular morphogenesis and maintenance of the integrity of the glomerular filtration barrier is poorly understood. Recently the integrin α3 subunit was selectively deleted in the podocyte, which resulted in mice that developed massive proteinuria in the first week of life and nephrotic syndrome by 5–6 weeks of age (Sachs et al., 2006). Newborn mice had complete podocyte foot process effacement and the glomeruli of the 6 week old mice were severely sclerosed, demonstrated a disorganized GBM and prominent protein casts in dilated proximal tubules. In this study we show that selectively deleting αsβ1 integrins in the podocyte resulted in 1) normal morphogenesis of the glomerulus, despite podocyte abnormalities; 2) a defective glomerular filtration barrier present at birth; 3) podocytes loss over time; 4) capillary loop and mesangium degeneration with little evidence of glomerulosclerosis and 5) the development of end stage kidneys characterized by both tubulointerstitial and glomerular pathology by 3 to 6 weeks of age. Taken together these results demonstrate that although the injury in the β1 integrin null mouse is more severe and has some differences in pattern, the overall phenotype is similar to that found in mice where the α3 integrin subunit is selectively deleted in podocytes. This suggests that integrin α3β1 is the principal integrin required to maintain the structural integrity of the glomerulus and other αsβ1 integrins play a relatively minor role.

The end stage kidneys of the pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice were characterized by severe tubulointerstitial disease in addition to the glomerular pathology. This was likely a consequence of the heavy glomerular proteinuria that results in interstitial mononuclear cell accumulation and activation of interstitial fibroblasts to deposit collagens in the tubulointerstitial compartment of the kidney (Eddy, 1994; Remuzzi, 1995; Remuzzi et al., 1997). As the defects in the GBM also correlated with the decreased number of podocytes and proteinuria, it is probable that the GBM changes result from podocyte loss and heavy proteinuria, rather than lack of β1 integrin function by the podocytes per se during GBM development.

In contrast to the newborn total integrin α3-null mouse, where in addition to the podocyte abnormalities the GBM was disorganized and capillary loop numbers were reduced (Kreidberg et al., 1996), the mutant mice in this study showed normal glomerular morphogenesis, GBM formation as well as expression of slit diaphragm and key cytoskeletal proteins. The differences in glomerular morphogenesis between these two mice may be because: i) sufficient αsβ1 integrins are expressed by the podocytes prior to Cre-mediated excision, as podocin is expressed at the S-shape body stage of development (Moeller et al., 2003) ii) αsβ1 integrins might still be expressed by the podocytes following cre expression due to inefficient deletion of β1 integrin; iii) GBM might be predominantly derived from and/or organized by the endothelial cells in the pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice, as both podocytes and the endothelium are known to contribute to formation of the GBM (Abrahamson, 1985; St John and Abrahamson, 2001); and iv) over-expression of αv- or β4-containig integrins or dystroglycan might compensate for the lack of αsβ1 integrins. This possibility, however, appears unlikely as expression of these receptors was similar in both pod-Cre; β1flox/flox and β1flox/flox mice (not shown).

Although the overall phenotypes of the podocyte specific α3- and β1-null mice were similar, there were some discrepancies. The earlier onset and increased severity of injury in the pod-Cre; β1flox/flox could be due to the loss of interactions of podocytes with the GBM via the collagen binding receptors, integrins α1β1and α2β1 and the laminin receptor integrin α6β1 which are expressed by podocytes during development (Korhonen et al., 1990; Rahilly and Fleming, 1992). Furthermore, we recently demonstrated that integrin α3β1 transdominantly inhibits integrin αvβ3-dependent function (Borza et al., 2006) and podocytes express integrin αvβ3 in vivo (Borza et al in press J. Am. Soc. Neph.). Thus deleting integrin α3β1 integrin might enhance podocyte adhesion to the GBM by increasing integrin αvβ3 affinity and avidity.

One of the striking and surprising differences in phenotype between our mice and the pod-Cre; α3flox/flox mice is that the GBM in our mice is relatively normal compared to the thickening and severe lamellations seen in that mouse. Furthermore our results in the GBM contrast with the improperly deposited epidermal BM in mice null for β1 integrin in keratinocytes (Brakebusch et al., 2000; Raghavan et al., 2000), however these changes might be organ specific as the BM is normal in mice where the β1 integrin was specifically deleted in the mammary gland (Li et al., 2005). A possible explanation for the discrepancy in results between the pod-Cre; α3flox/flox and the pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice is that integrin α3β1 might negatively regulate integrin α2β1-dependent glomerular collagen production. This hypothesis is based on the observation that integrin α2β1 is a positive regulator of collagen synthesis (Ivaska et al., 1999); integrin α2β1 function can be negatively regulated by the expression of other integrin family members; and deleting integrin α2β1 results in diminished collagen IV production in models of glomerular injury (Pozzi and Zent unpublished data).

The abnormality of the glomerular filtration barrier was present at birth when only abnormal foot process formation was present and this phenotype worsened with time and correlated with podocyte apoptosis and loss. We were unable to determine whether the loss of podocytes was due to lack of β1 integrin-dependent cell adhesion to the GBM or due to cell injury and apoptosis as a consequence of lack of β1 integrin. However the temporal association of podocyte loss with increased hydrostatic pressure due to urinary flow following birth suggests the increase in force exerted on the podocytes may have induced podocyte detachment and subsequent apoptosis.

One of the most interesting features of the podocyte β1-null mouse was the rapidity with which the glomeruli degenerated and the lack of glomerular fibrosis relative to the glomerular injury. This contrasts with mice deficient for specific collagen IV chains required for normal GBM formation, where glomerulosclerosis and proteinuria occurred (Cosgrove et al., 1996; Miner and Sanes, 1996) but the mice lived significantly longer than the podocyte integrinβ1-null mice. Similarly, mice deficient for ILK (R. Zent, unpublished data) (Dai et al., 2006; El-Aouni et al., 2006) or the integrin α3 subunit in the podocytes (Sachs et al., 2006) as well as lacking proteins required for normal slit diaphragm formation (i.e. podocin and CD2-associated protein) (Roselli et al., 2004) (Shih et al., 1999) also had foot process effacement, proteinuria, and developed severe glomerulosclerosis prior to developing end stage kidney. In addition to these genetic models, when 40% of podocytes were destroyed in rats by diphtheria toxin, the primary lesion observed was glomerulosclerosis (Wharram et al., 2005), which is consistent with the theory that if sufficient podocytes detach leaving a naked GBM, a circumscribed region of focal segmental sclerosis will initially form and eventually result in global glomerulosclerosis (Kriz, 2002). Thus foot process and slit diaphragm abnormalities or loss of up to 40% of podocytes in glomeruli does not explain why pod-Cre; β1flox/flox did not develop glomerulosclerosis.

In an attempt to explain the lack of glomerulosclerosis and the severe mesangiolysis in our mouse model, we noted that the glomerular phenotype of the pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice at 3 weeks of age had many features similar to those seen in mice expressing one hypomorphic VEGF-A allele (Eremina et al., 2006). Both these mice have dilated capillary loops and severe abnormalities within the mesangium. The phenotype in the VEGF hypomorphic mouse is proposed to be due to a requirement of podocyte-dependent VEGF production for both endothelial cell proliferation and survival, and disruption of the endothelial compartment leads to the mesangial defects (Eremina et al., 2006). Since the pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice demonstrate significant podocyte loss and the principal source of VEGF in the glomerulus is the podocytes, we postulate that when sufficient podocytes are lost in this mouse, the endothelial cells undergo apoptosis due to their dependence on this angiogenic factor, or other factors produced by the podocyte, for survival. The lack of VEGF would not explain the mesangium phenotype as mesangial cells do not express receptors for VEGF (Eremina et al., 2006). However mesangial cells do require PDGF-β secretion by endothelial cells for their survival (Bjarnegard et al., 2004). Thus with progressive podocyte loss in the pod-Cre; β1flox/flox, we propose that the glomerulus loses VEGF and probably other podocyte-specific growth factors production, which results in endothelial cell death. The loss of growth factor production from both these cells types subsequently results in the inability of the glomerulus to maintain integrity of the mesangium.

In conclusion we provide evidence that podocyte expression of αsβ1 integrins is required for the normal formation and integrity of the glomerular filtration barrier. Although the GBM appears to form relatively normally in newborn pod-Cre; β1flox/flox mice, podocyte foot process effacement and proteinuria is seen. With the increase in glomerular hydrostatic pressure, podocytes are lost from the glomerulus, which promotes rapid destruction of the capillary loops and mesangium with little glomerulosclerosis. The rapidly degenerating glomeruli promote tubulointerstitial disease which is likely due to the increased proteinuria. This phenotype is for the most part similar but more severe than that seen in mice lacking the α3 integrin subunit in podocytes, where proteinuria and glomerulosclerosis are the primary features (Sachs et al., 2006), suggesting that in addition to integrin α3β1, other αsβ1 integrins play a role in maintaining the glomerular filtration barrier.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Elaine Fuchs for providing the integrin β1flox/flox mice. This work was supported by R01-CA94849 (AP); R01-DK74359 (AP); O’Brien Center Grant P50-DK39261-16 (AP, RZ, RCH); P01 DK65123 (DBB, BGH, RZ, AP, JHM), RO1-DK69921 (RZ); R01-DK064687 (JHM), RO1-DK51265 (RCH), Merit award from the Department of Veterans Affairs (RZ, RCH), Established Investigator Award from the American Heart Association (JHM), Grant in Aid American Heart Association (RZ), Research Grant from the National Kidney Foundation of Eastern Missouri and Metro East (GJ).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abrahamson DR. Origin of the glomerular basement membrane visualized after in vivo labeling of laminin in newborn rat kidneys. J Cell Biol. 1985;100:1988–2000. doi: 10.1083/jcb.100.6.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aumailley M, et al. A simplified laminin nomenclature. Matrix Biol. 2005;24:326–332. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjarnegard M, et al. Endothelium-specific ablation of PDGFB leads to pericyte loss and glomerular, cardiac and placental abnormalities. Development. 2004;131:1847–57. doi: 10.1242/dev.01080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borza CM, et al. Integrin alpha3beta1, a novel receptor for alpha3(IV) noncollagenous domain and a trans-dominant Inhibitor for integrin alphavbeta3. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:20932–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601147200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brakebusch C, et al. Skin and hair follicle integrity is crucially dependent on beta 1 integrin expression on keratinocytes. Embo J. 2000;19:3990–4003. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.15.3990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, et al. Lack of integrin alpha1beta1 leads to severe glomerulosclerosis after glomerular injury. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:617–30. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63326-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove D, et al. Collagen COL4A3 knockout: a mouse model for autosomal Alport syndrome. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2981–92. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.23.2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai C, et al. Essential role of integrin-linked kinase in podocyte biology: Bridging the integrin and slit diaphragm signaling. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2164–75. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006010033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Arcangelis A, et al. Synergistic activities of alpha3 and alpha6 integrins are required during apical ectodermal ridge formation and organogenesis in the mouse. Development. 1999;126:3957–3968. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.17.3957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPersio CM, et al. alpha3beta1 Integrin is required for normal development of the epidermal basement membrane. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:729–42. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.3.729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPersio CM, et al. alpha 3A beta 1 integrin localizes to focal contacts in response to diverse extracellular matrix proteins. J Cell Sci. 1995;108(Pt 6):2321–36. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.6.2321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPersio CM, et al. (α)3(β)1 and (α)6(β)4 integrin receptors for laminin-5 are not essential for epidermal morphogenesis and homeostasis during skin development [In Process Citation] J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 17):3051–3062. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.17.3051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy AA. Experimental insights into the tubulointerstitial disease accompanying primary glomerular lesions. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1994;5:1273–87. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V561273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Aouni C, et al. Podocyte-specific deletion of integrin-linked kinase results in severe glomerular basement membrane alterations and progressive glomerulosclerosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:1334–44. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005090921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eremina V, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor a signaling in the podocyte-endothelial compartment is required for mesangial cell migration and survival. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:724–35. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005080810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eremina V, et al. Glomerular-specific alterations of VEGF-A expression lead to distinct congenital and acquired renal diseases. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:707–16. doi: 10.1172/JCI17423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georges-Labouesse E, et al. Absence of integrin alpha 6 leads to epidermolysis bullosa and neonatal death in mice. Nat Genet. 1996;13:370–373. doi: 10.1038/ng0796-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas CS, et al. Glomerular and renal vascular structural changes in alpha8 integrin-deficient mice. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:2288–96. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000082999.46030.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartner A, et al. The alpha8 integrin chain affords mechanical stability to the glomerular capillary tuft in hypertensive glomerular disease. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:861–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64909-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzman LB, et al. Nephrin localizes to the slit pore of the glomerular epithelial cell. Kidney Int. 1999;56:1481–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes R. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110:673–87. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivaska J, et al. Integrin alpha2beta1 mediates isoform-specific activation of p38 and upregulation of collagen gene transcription by a mechanism involving the alpha2 cytoplasmic tail. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:401–16. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.2.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinowska TC, et al. Epithelial development and differentiation in the mammary gland is not dependent on alpha 3 or alpha 6 integrin subunits. Dev Biol. 2001;233:449–67. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korhonen M, et al. The alpha 1-alpha 6 subunits of integrins are characteristically expressed in distinct segments of developing and adult human nephron. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:1245–1254. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.3.1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreidberg JA, et al. Alpha 3 beta 1 integrin has a crucial role in kidney and lung organogenesis. Development. 1996;122:3537–3547. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.11.3537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreidberg JA, Symons JM. Integrins in kidney development, function, and disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2000;279:F233–42. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.279.2.F233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriz W. Podocyte is the major culprit accounting for the progression of chronic renal disease. Microsc Res Tech. 2002;57:189–95. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, et al. Beta1 integrins regulate mammary gland proliferation and maintain the integrity of mammary alveoli. Embo J. 2005;24:1942–53. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner JH. Renal basement membrane components. Kidney Int. 1999;56:2016–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner JH. Building the glomerulus: a matricentric view. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:857–61. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004121139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner JH, Li C. Defective glomerulogenesis in the absence of laminin alpha5 demonstrates a developmental role for the kidney glomerular basement membrane. Dev Biol. 2000;217:278–89. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner JH, et al. The laminin alpha chains: expression, developmental transitions, and chromosomal locations of alpha1-5, identification of heterotrimeric laminins 8–11, and cloning of a novel alpha3 isoform. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:685–701. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.3.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner JH, Sanes JR. Collagen IV alpha 3, alpha 4, and alpha 5 chains in rodent basal laminae: sequence, distribution, association with laminins, and developmental switches. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:879–91. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.3.879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner JH, Sanes JR. Molecular and functional defects in kidneys of mice lacking collagen alpha 3(IV): implications for Alport syndrome. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:1403–13. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.5.1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller MJ, et al. Podocyte-specific expression of cre recombinase in transgenic mice. Genesis. 2003;35:39–42. doi: 10.1002/gene.10164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor MJ, et al. Ablation of beta1 integrin in mammary epithelium reveals a key role for integrin in glandular morphogenesis and differentiation. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:717–28. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200503144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noakes PG, et al. The renal glomerulus of mice lacking s-laminin/laminin beta 2: nephrosis despite molecular compensation by laminin beta 1. Nat Genet. 1995;10:400–6. doi: 10.1038/ng0895-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan S, et al. Conditional ablation of beta1 integrin in skin. Severe defects in epidermal proliferation, basement membrane formation, and hair follicle invagination. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:1149–60. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.5.1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahilly MA, Fleming S. Differential expression of integrin alpha chains by renal epithelial cells. J Pathol. 1992;167:327–34. doi: 10.1002/path.1711670311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remuzzi G. Abnormal protein traffic through the glomerular barrier induces proximal tubular cell dysfunction and causes renal injury. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 1995;4:339–42. doi: 10.1097/00041552-199507000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remuzzi G, et al. Understanding the nature of renal disease progression. Kidney Int. 1997;51:2–15. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roselli S, et al. Podocin localizes in the kidney to the slit diaphragm area. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:131–9. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64357-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roselli S, et al. Early glomerular filtration defect and severe renal disease in podocin-deficient mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:550–60. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.2.550-560.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs N, et al. Kidney failure in mice lacking the tetraspanin CD151. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:33–9. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200603073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih NY, et al. Congenital nephrotic syndrome in mice lacking CD2-associated protein. Science. 1999;286:312–5. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5438.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St John PL, Abrahamson DR. Glomerular endothelial cells and podocytes jointly synthesize laminin-1 and -11 chains. Kidney Int. 2001;60:1037–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.0600031037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St John PL, et al. Glomerular laminin isoform transitions: errors in metanephric culture are corrected by grafting. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;280:F695–705. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.280.4.F695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wharram BL, et al. Podocyte depletion causes glomerulosclerosis: diphtheria toxin-induced podocyte depletion in rats expressing human diphtheria toxin receptor transgene. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:2941–52. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005010055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]