Abstract

In response to ocular herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) infection in mice a rapid induction or increase in the local expression of chemokines including CXCL10 is found. The present study investigated the role of the receptor for CXCL10, CXCR3, in the host response to corneal HSV-1 infection. Mice deficient in CXCR3 (CXCR3−/ −) were found to have an increase in infectious virus in the anterior segment of the eye by day 7 post infection. Coinciding with the increase, selective chemokines including CCL2, CCL3, CCL5, CXCL9, and CXCL10 were elevated in the anterior segment of the HSV-1-infected CXCR3−/− mice. In contrast, there was a time-dependent reduction in the recruitment of NK cells (NK1.1+CD3−) into the anterior segment of CXCR3 −/− mice. A reduction in NK cells residing in the anterior segment of mice following anti-asialo GM1 antibody treatment resulted in an increase in infectious virus. No other leukocyte populations infiltrating the tissue were modified in the absence of CXCR3. Collectively, the loss of CXCR3 expression specifically reduces NK cell mobilization into the cornea in response to HSV-1.

Keywords: HSV-1, CXCR3, NK cell

INTRODUCTION

The host response to ocular herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) infection includes the recruitment of leukocytes into the infected tissue and subsequent release of soluble mediators including pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, matrix metalloproteinases, and angiogenic factors that lead to corneal scarring and angiogenesis of the avascular tissue.1 Promoting the infiltration of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) and mononuclear cells are chemokines including macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (MIP-2, CXCL2), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1, CCL2), RANTES (CCL5), and IFN-inducible protein (IP) 10/ CXC chemokine ligand (CXCL)10.2 Of these, CXCL10 is one of the first detectable chemokine expressed within the cornea following HSV-1 infection, and neutralization of this chemokine suppresses the inflammatory cascade as measured by infiltrating leukocytes and production of chemokines including CCL5, and macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α, CCL3).3 This observation has led to the hypothesis that CXCL10 is a (the) sentinel chemokine within the cornea that orchestrates the inflammatory cascade associated with ocular herpes infection.4

Similar to CXCL10, monokine induced by IFN- γ (Mig, CXCL9) and IFN-inducible T cell α chemoattractant (I-TAC, CXCL11) share the same receptor, CXCR3, which is preferentially expressed on activated T lymphocytes of the Th1 phenotype.5,6 Not only do CXCR3 ligands direct Th1 cell migration but they also have been found to recruit plasmacytoid dendritic cells to inflamed tissue.7 These specialized antigen presenting cells are a rich source of IFN-α in response to virus infection.8 Cytokine expression to ocular HSV-1 infection seems to dictate the degree of resistance to the virus.

Specifically, the Th1 cytokine IFN- γ is associated with resistance to HSV-1 whereas Th2 cytokines including IL-4 or IL-10 are thought to promote infection or suppress the inflammatory response suggesting Th1 cytokine expression may benefit the host by suppressing HSV-1 replication.9–13 Based on these observations, we hypothesized CXCR3 deficient (CXCR3 −/−) mice would be more susceptible to HSV-1 infection in terms of an increase in infectious virus recovered in the tissue associated with a drop in Th1 cytokine production. Our results suggest the absence of CXCR3 is conducive to HSV-1 replication in the anterior segment of the eye in a time-dependent fashion which is associated with a reduction in recruitment of NK cells but not CD4+ T cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus and cells

Propagation of and plaque assays using African green monkey kidney fibroblasts (Vero cells, ATCC CCL-81, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were carried out in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, gentamicin (Invitrogen, Calsbad, CA.) and antibiotic-antimycotic solution (Invitrogen) at 37° C, 5% CO2, and 95% humidity as previously described.14 HSV-1 stocks (McKrae strain) were propagated in Vero cells. Stocks were stored at −80° C at a concentration of 1x108 plaque forming units (pfu) and diluted in RPMI-1640 immediately before use.

Mice

Male and female wild type (WT) C57BL/6 mice obtained from The Jackson Labs (Bar Harbor, ME) and CXCR3 deficient mice on a C57BL/6 background (CXCR3 −/−)15 were used to establish a colony in the vivarium at the Dean A. McGee Eye Institute (Oklahoma City, OK). CXCR3 −/− mice were genotyped to validate the absence of CXCR3 gene expression using sense (5′-AAGCTTCGACAGATATCTGAG-3′) and anti-sense (5′-TAGTTGGCTGATAGGTAGATG-3′) oligonucleotide primers to amplify a product of 135 bp by end point PCR (1 cycle at 94° for 6 min followed by 35 cycles of 94° C/30 sec, 55° C/60 sec, and 72° C/60 sec followed by 72° C for 6 min). The cornea of anesthetized age (5–8 weeks old) and sex-matched (male and female) C57BL/6 and CXCR3 −/− mice were scarified using a 25-gauge needle, and 500 plaque forming units (pfu) of HSV-1 was applied in a volume of 3.3 μl in RPMI-1640. At the indicated time post infection (p.i.), the mice were euthanized and perfused with PBS (pH 7.4). The anterior segments (corneas and iris) were removed and placed in PBS containing 1X protease inhibitor cocktail set I (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) for detection of chemokines and cytokines by ELISA or RPMI 1640 medium for determination of virus quantity by plaque assay. The tissue was homogenized in 500 μl of solution and the supernatant was clarified (10,000xg, 1 min) and stored at −80° C or used immediately for the detection of virus (by plaque assay) or chemokine/cytokine content (by ELISA). All procedures were approved by The University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center and Dean A McGee Eye Institute animal use committees.

Viral plaque assay

Clarified supernatant from homogenized tissue was serially diluted and placed (100 μl) onto Vero cell monolayers in 96-well cultured plates. After a 1-hr incubation at 37° C in 5% CO2, and 95% humidity, the supernatants were discarded, and 75 μl of an overlay solution (0.5% methylcellulose in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, gentamicin, and antibiotic/antimycotic solution) was added on top of the monolayer. The cultures were incubated at 37° C in 5% CO2, and 95% humidity for 28–32 h to observe plaque formation, and the amount of infectious virus was reported as pfu/tissue. Supernatants obtained from uninfected mice rendered no detectable plaques.

ELISA and suspension array analysis

The detection of CXCL9, CXCL10, and TNF-α was performed using commercially available kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The sensitivity for the detection of the chemokines/cytokines ranged from 2.0–13.0 pg/tissue. Each sample was assayed in duplicate along with a standard provided in the kit to generate a standard curve used to determine the unknown amount of targeted cytokine/chemokine. Standard curves did not fall below a correlation coefficient of .9950. The detection of CXCL1, CCL2, CCL3, and CCL5 were performed using a suspension array system (Bioplex, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Samples were analyzed in duplicate along with a standard provided. The weight of each tissue was used to normalize amount of cytokine/chemokine per milligram (mg) of tissue weight.

Preparation of anterior segment single cell suspensions

At 3, 5, or 7 days p.i. anesthetized mice were perfused with PBS, and the anterior segments were removed and incubated in a 3 mg/ml solution of collagenase type I (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) at 37° C. Every twenty min for 60–90 min, the tissue was triturated using a p1000 pipetman. Following the incubation period, the digested tissue was passed through a 70 μm cell strainer (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA), and the cell strainer was flushed with 5.0 ml of RPMI-1640 containing 10% FBS. Cells were washed twice with PBS containing 1% BSA. Each cornea from each eye constituted one sample analysis that was divided in thirds for subsequent analysis by flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry

Single cell suspensions from the anterior segment were incubated with four μl of anti-mouse CD16/CD32 (Fc γ III/II receptor) (2.4G2) (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) for 20 min to prevent non-specific binding of fluoresceinated mAbs. The cells were then washed with 1.0 ml of PBS/1% BSA and resuspended in 100 μl PBS/1% BSA in which single cell suspensions were triple-labeled with PE-conjugated anti-CD3 or Gr1, FITC-conjugated anti-CD4, −CD8, −F4/80, or −NK1.1, and PE-Cy5-conjugated anti-CD45 (clone 30-F11, BD Pharmingen). The cells were incubated for 30 min on ice in the dark, washed twice with 1 ml PBS containing 1% BSA (300xg, 5 min at 4° C), and resuspended in 1% paraformaldehyde (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO). After a 60 min incubation at room temperature, the cells were centrifuged (300xg, 5 min at 4° C) and resuspended in 1.0 ml PBS containing 1% BSA. Prior to analysis 30 μl of a solution containing 20,800 CountBright counting beads (Invitrogen, Eugene, Oregon) was added to each sample. Single Cell suspensions were analyzed on a Coulter Epics XL flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL) and the data analyzed using EXPO 32 ADC software (Beckman Coulter). The samples were gated on CD45 expressing cells, and the percentages of CD4 T cells, NK cells, F4/80+ cells, and Gr-1+ cells were determined under this gate setting. Samples were analyzed for 1100 sec with the absolute number of leukocytes (CD45high) contained within the tissue determined by the number of events within the established gate normalized to the reference bead count/sample. Isotypic control antibodies were included in the analysis to establish background fluorescence levels.

Whole mount staining for CXCR3 expression

At day 7 p.i., WT and CXCR3 −/− mice were anesthetized, exsanguinated, and the eyes were removed and placed into 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes containing 0.5 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma) in PBS. After a 15 min incubation, the corneas were removed from the eyes, placed in 4% paraformaldehyde and incubated overnight at room temperature. Corneas were then washed 3x with 1.0 ml PBS containing 1% Triton X-100 (Sigma) for 10 min. After the final wash, corneas were incubated PBS containing 10% goat serum for 60 min at room temperature. Next, the corneas were incubated with 1–2 μg rabbit anti-CXCR3 polyclonal antibody (Zymed, South San Francisco, CA) in 100 μl PBS for 180 min at 37° C. After the incubation period, the corneas were washed 3x in PBS containing 1% Triton X-100 and 1–2 μg of FITC conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (Zymed) and Alexa fluor 647 conjugated anti-CD3 antibody (BD Pharmingen) was added in 100 μl PBS. Following a 180 min incubation at 37° C in the dark, the corneas were washed 3x in PBS containing 1% Triton X-100. Next, 50 μl mounting medium containing DAPI (4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Vector Laboratories) was added to the corneas and samples were incubated at 4° C overnight in the dark. The following day, corneas were placed onto coverslips and an incision was made in each cornea, encompassing approximately 50% of the tissue (to facilitate flattening of the tissue). Slides were placed on top of the coverslip. The slides were kept at 4° C in the dark until analysis by confocal microscopy.

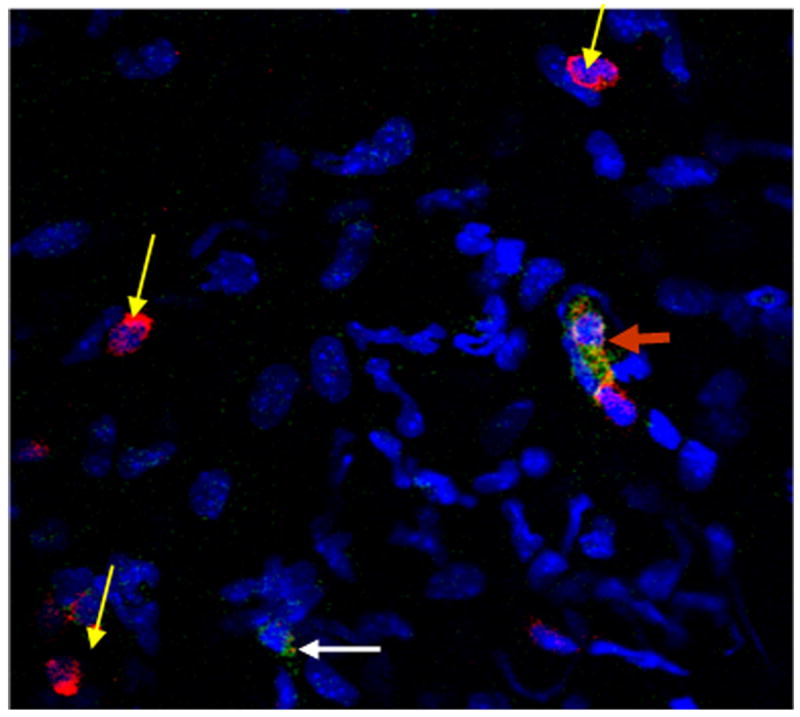

Confocal microscopy

Corneas (n=2) were imaged using an Olympus IX81-FV500 epifluorescence/confocal laser-scanning microscope with a UApo 40x water immersion lens. Samples were excited at 405, 488, and 633 nm wavelength lasers. Scanning images were taken with a step size of 5 μm, and image analysis was performed using FLUOVIEW software (Olympus).

Depletion of NK cells

One day prior and 3 days post HSV-1 infection, rabbit anti-mouse asialoGM1 polyclonal antibody or normal rabbit serum was administered retro-orbitally into mice in a total volume of 40 μl per dose administered. Mice were exsanguinated 7 days p.i. and the corneas were collected and assessed for NK cell (defined as NK1.1+CD3−) content by flow cytometry or assayed for viral content by plaque assay.

Statistics

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Scheffe’s post-hoc multiple comparison test were used to determine significance (p<.05) of differences between the wild type and gene knockout mice. All statistical analysis was performed using the GBSTAT program (Dynamic Microsystems, Silver Springs, MD).

RESULTS

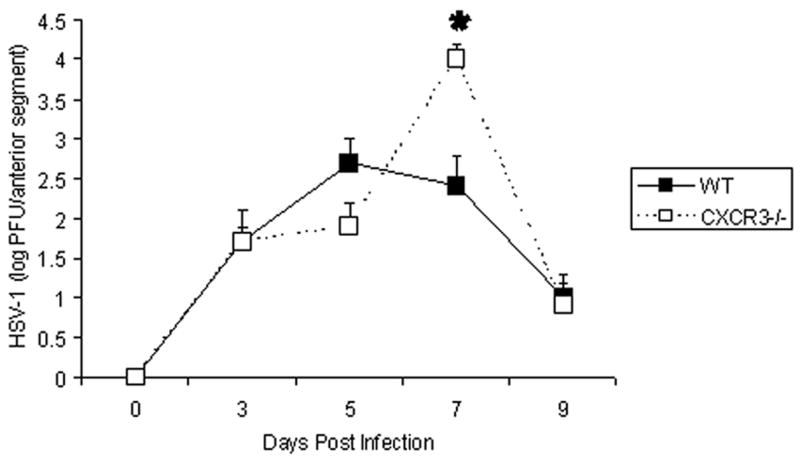

CXCR3 deficient mice possess higher virus titers in the anterior segment following corneal infection

CXCR3 transcript expression is elevated in the eye following infection with HSV-1.3 To determine the impact of CXCR3 expression on local virus replication and spread, C57BL/6 WT or CXCR3 −/− mice were infected with HSV-1. The loss of CXCR3 expression did not affect virus replication during the initial stages of acute infection (day 3 or day 5 post infection, p.i.) (Fig. 1). However, by day 7 p.i., an increase in infectious virus was recovered in the anterior segment of CXCR3 −/− mice (Fig. 1). The increase was only transient since both WT and CXCR3 −/− mice had similar levels by day 9 p.i. (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

CXCR3 deficient mice possess elevated viral titers seven days post infection. C57BL/6 (WT) and CXCR3 deficient (CXCR3 −/−) mice (n=9–18 mice/group) were infected with 500 pfu/eye HSV-1. At day 0–9 post infection, the mice were euthanized and the anterior segments (cornea and iris) were removed using a dissecting microscope, homogenized, and assayed for infectious virus by plaque assay. The data are expressed as the mean log PFU HSV-1 ± SEM and are pooled from 3–6 experiments with n=3 mice/group/experiment. *p<.05 for comparison of the WT to CXCR3 −/− mice.

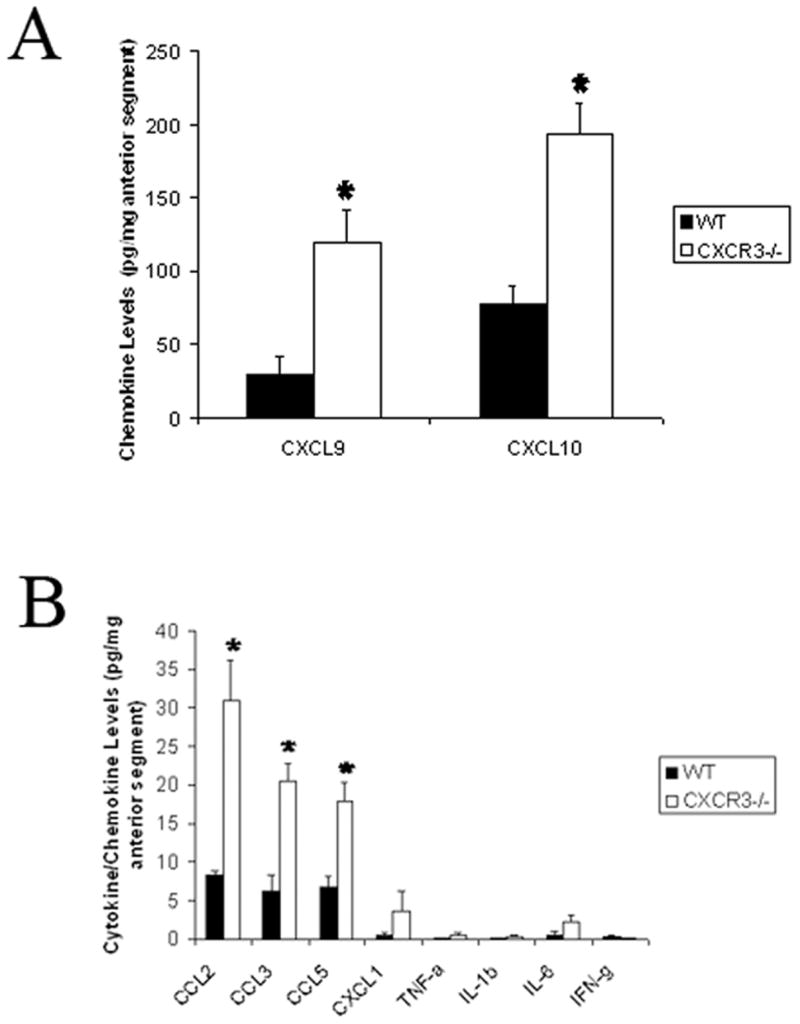

Chemokine levels are elevated in the eye of CXCR3 −/− mice

Since virus titers were increased in the CXCR3 −/− mice following HSV-1 infection, we next evaluated the expression of inflammatory molecules including monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (CCL2), macrophage inflammatory protein 1α (CCL3), regulated upon activation, normal T expressed (RANTES, CCL5), KC (CXCL1), monokine induced by interferon- γ (Mig, CXCL9), IFN-inducible protein 10 kilodaltons (CXCL10), IFN-γ and TNF-α that had previously been found to be expressed in the eye following HSV-1 infection.2,3 At the earlier time points p.i., there was no significant difference in the expression of CCL2, CCL3, CCL5, CXCL1, CXCL9, or CXCL10 in the anterior segment comparing the C57BL/6 WT to CXCR3 −/− mice (data not shown). By day 7 p.i., all chemokines analyzed were increased in the anterior segment of CXCR3 −/−mice. Specifically, the CXCR3 ligands CXCL9 and CXCL10 were increased 2–4 fold in the CXCR3 −/− mice (Fig. 2A) whereas CCL2, CCL3, and CCL5 were elevated 3–4 fold in the CXCR3 −/− mouse anterior segment (Fig. 2B). CXCL1 was also elevated in the CXCR3 −/− mouse anterior segment by 6 fold but the variability negated significance (Fig. 2B). By comparison, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α were not significantly elevated in the CXCR3 −/− mice in comparison to WT mice (Fig. 2B). Likewise, IFN- γ levels were increased in the WT mouse anterior segment in comparison to the CXCR3 −/− group but the levels did not reach significance. Based on these results, we surmise the increase in virus found in the anterior segment of the eye may influence the expression of some chemokines produced by resident cells and infiltrating leukocytes in response to HSV-1 infection.

FIG. 2. Chemokine expression in the anterior segment of CXCR3 −/− mice is elevated following HSV-1 infection.

C57BL/6 (WT) and CXCR3 deficient (CXCR3 −/−) mice (n=9–13 mice/group/chemokine) were infected with 500 pfu/eye HSV-1. At day 0–7 post infection, the mice were euthanized and the anterior segments were removed using a dissecting microscope, homogenized, and assayed for the indicated chemokine/cytokine by ELISA or suspension array. The data are expressed as the mean pg/mg ± SEM and are pooled from 3–4 experiments with n=3–4 mice/group/experiment. *p<.05 for comparison of the WT to CXCR3 −/− mice.

Changes in NK cell recruitment to the cornea of HSV-1-infected CXCR3 −/− mice

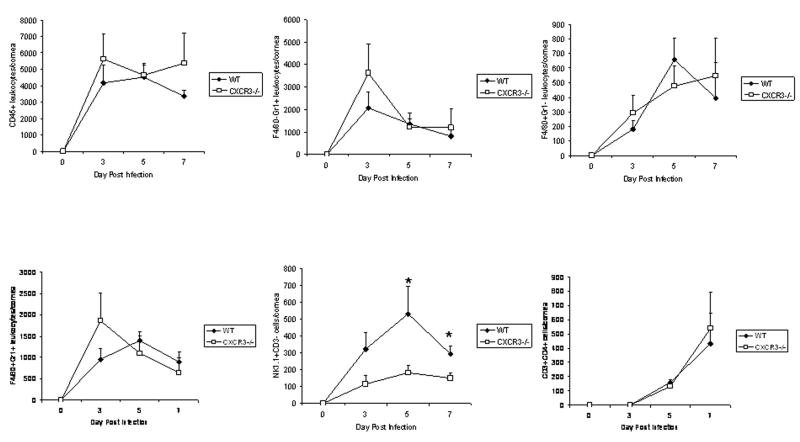

Since changes were noted in chemokine expression in the anterior segment of CXCR3 −/−mice following HSV-1 infection, one possible outcome might be reflected by leukocytes recruited to the site of infection. Confocal microscopy revealed the presence of CXCR3-expressing cells residing in the cornea following HSV-1 infection (Fig. 3). CXCR3-expressing cells were not detected in CXCR3 −/− mice. To quantify the levels of leukocytes infiltrating the cornea of mice, single cell suspensions from dissociated corneas were analyzed for leukocyte populations by flow cytometry. The results show no difference in the number of total leukocytes (CD45high), neutrophils (F4/80−Gr1+), macrophages (F4/80+Gr1−), or CD4+ T cells residing in the cornea following HSV-1 infection comparing WT to CXCR3 −/− mice (Fig. 4). However, there was a reduction in NK cell migration into the infected cornea of CXCR3 −/− mice in response to HSV-1 at day 5 and day 7 p.i. (Fig. 4).

FIG. 3. CXCR3 expression by cells infiltrating the cornea.

C57BL/6 (WT) were infected with 500 pfu/eye HSV-1. At day 7 post infection, the mice were euthanized and the corneas were removed using a dissecting microscope and processed for CXCR3 expression using FITC-conjugated antibody to CXCR3 (green) and T cell infiltration Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated anti-CD3 antibody (red). Flat mounts of corneas were prepared and incubated with mounting media containing Dapi (blue) to stain nuclei. The flat mounts were analyzed for CXCR3-expressing cells (white arrow), CD3-expressing cells (yellow arrow), and cells co-expressing CXCR3 and CD3 (red arrow).

FIG 4. A lack of CXCR3 results in a reduction in NK cell infiltration into the cornea following HSV-1 infection.

C57BL/6 (WT) and CXCR3 deficient (CXCR3 −/−) mice (n=6–10 mice/group/time point) were infected with 500 pfu/eye HSV-1. At day 0–7 post infection, the mice were euthanized and the corneas were removed and processed for subsequent phenotypic analysis of infiltrating cell populations by flow cytometry. The data are expressed as the mean number of cells ± SEM for each phenotypically-defined population. *p<.05 for comparison of the WT to CXCR3 −/− mice. We were unable to recover a significant population of leukocytes (defined as CD45hi) in uninfected cornea using this technique.

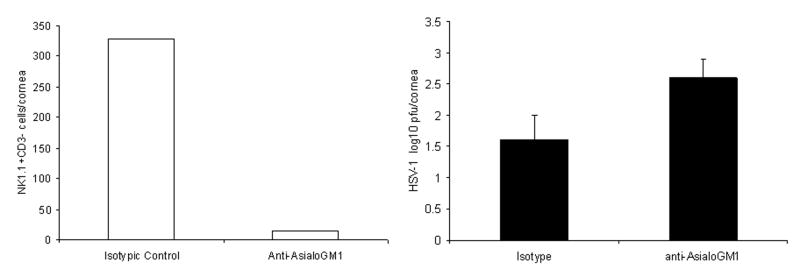

To further define the importance of NK cells as a deterrent to HSV-1 replication, WT mice were depleted of NK cells and cornea virus titers determined by plaque assay. The results revealed a 1 log increase in the amount of infectious virus recovered in the cornea of NK cell-depleted mice in comparison to isotypic control-treated animals suggesting NK cells contribute to viral surveillance within the cornea of mice (Fig. 5).

FIG 5. Depletion of NK cells results in a modest increase in HSV-1 titers in the cornea following infection.

C57BL/6 (WT) mice (n=3/group) were treated with 40 μl of rabbit anti-asialo GM1 or control rabbit IgG one day prior to and 72 hr post infection. At day 7 post infection, the mice were euthanized and the corneas were removed and assayed for (A) NK cell content by flow cytometry or (B) virus titer by plaque assay. The data is presented as mean ± SEM.

DISCUSSION

The current investigation sought to determine the role of CXCR3 in the host response to ocular HSV-1 infection. In comparing virus titer in the anterior segment of the eye, there was a modest increase in virus recovered in CXCR3 −/− mice in a time-dependent fashion. The elevation in virus yield in the CXCR3 −/− mice correlated with an increase in CCL2, CCL3, CCL5, CXCL9, and CXCL10 protein levels. Previous studies have reported CpG motifs contained in HSV-1 DNA16 elicits TLR9 activation17 which has been found to drive CXCL9 and CXCL10 expression in the cornea following HSV-1 infection.18 Therefore, it is likely an increase in viral protein antigen expression or increased viral DNA in the anterior segment of CXCR3 −/− mice drives the expression of chemokines. However, not all chemokines evaluated were modified (i.e., CXCL1) and none of the cytokines examined were significantly different comparing WT to CXCR3 −/− mice. We have previously reported cytokine/chemokine expression in the cornea is not associated entirely with the level of HSV-1 present suggesting other mechanisms also influence chemokine expression.19

Since increases in the expression of chemokines in the anterior segment of HSV-1-infected CXCR3 −/− mice were observed, we next sought to evaluate the recruitment of leukocytes into these tissues at times p.i. The cornea provided a window in which the measurement of leukocyte infiltration could be consistently and reproducibly accomplished. Even though there was a significant increase in CCL2, CCL3, CCL5, CXCL9, and CXCL10 levels in the anterior segment of CXCR3 −/− mice compared to WT mice at day 7 p.i., there was no difference in the infiltration of leukocyte populations including CD4+ T cells into the cornea with the exception of NK cells. We have previously reported an early (day 3 p.i.) but transient deficiency of CD11b+ and Gr-1+ cells into the cornea of CCR5 deficient mice following HSV-1 infection.20 In that study, there were modest but insignificant changes in T cell infiltration into the cornea at day 7 p.i. The present findings also demonstrate the absence of an appreciable effect on CD4+ T cell infiltration into the cornea following HSV-1 infection which is consistent with a low percentage of CD3+ T cells that co-express CXCR3+ following infection. Taken together, it would appear the loss of CXCR3 or CCR5 does not significantly modify T cell infiltration into the eye following HSV-1 infection. Rather, CXCR3 and CCR5 deficiency appears to impact the host response to virus infection in the nervous system ultimately resulting in efficacious or detrimental outcomes depending on the viral pathogen/disease state.20–25

NK cells have previously been reported to be involved in the development of corneal scarring26,27 but their control of HSV-1 replication in the eye has been questioned.28 Specifically, the depletion of NK cells in SCID mice had no bearing on HSV-1 titers found in the cornea whereas adoptive transfer of T but not B cells significantly diminished virus replication. In the present study, NK cells were depleted in the cornea by greater than 90% using antibody to asialo GM1. In another study, we found the anti-asialo GM1 antibody treatment not only depletes NK cells and NKT cells but also depletes CD8+ T effector cells and total CD8+ but not CD4+ T cells infiltrating the HSV-1-infected nervous system (Wuest and Carr, submitted). Therefore, it is likely the anti-asialo GM1 antibody may have depleted CD8+ T cells in the WT mice. While the majority of T cells infiltrating the cornea are CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells regulate corneal HSV-1 infection even in the absence CD4+ T cells.27,29,30 Therefore, it is likely the combined loss of NK cells and CD8+ T cells following treatment with anti-asialo GM1 antibody contributed to the increase in HSV-1 recovered in the cornea in comparison to control antibody-treated animals.

In summary, our results point to a deficiency in the capacity of CXCR3 −/− mice to respond to ocular HSV-1 infection in a time-dependent manner evident by elevated levels of virus, a decrease in NK cell recruitment, and associated increase in selective chemokines expressed in the anterior chamber. Our hypothesis that CXCR3 −/− mice would show a reduction in ocular inflammation as a result of the loss of CXCL10 interaction with its receptor proved to be incorrect. However, the data suggest the lack of CXCR3 specifically impacts on NK cell migration to the cornea in response to HSV-1 infection evident by a time-dependent reduction in NK cell migration to the cornea. Ironically, in the absence of CXCR3 ligands including CXCL9 or CXCL10, we previously reported no difference in NK cell recruitment to the cornea in response to HSV-1.31 However, the absence of CXCR3 has been found to correspond with a reduction in NK cell recruitment to the nervous system of HSV-1 infected mice consistent with CXCR3 function on NK cells (Wuest and Carr, submitted). Currently, it is unknown why the behavior of NK cells is not consistent between animals deficient in CXCR3 versus those deficient in the CXCR3 ligands. One possibility is the redundancy that may occur between the CXCR3 ligands such that in the absence of one, another CXCR3 ligand can replace/substitute functionally in recruitment of CXCR3-expressing lymphocytes to the site of infection, in this case, the cornea. Alternatively, the only other known CXCR3 ligand, CXCL11, may also play a role. However, we feel this explanation unlikely. Specifically, multiple groups have reported cDNA and genomic sequences indicating C57BL/6 mice have a deletion at the base pair corresponding to +38 position in the mRNA sequence for CXCL11 (Pubmed accession numbers NT_109320, AK040051.1, and AK050012.1). This deletion is predicted to introduce a frame shift at the codon for amino acid (aa) 13 as well as a stop codon that would result in the truncation of the peptide to only 36 of 100 aa. CXCL11 activity would almost certainly be abolished as the N-loop (aa 12–17) required for chemokine receptor binding and essential glycosaminoglycan binding motifs in the C-terminal domain would be absent.32,33

Collectively, changing the dynamics of the inflammatory cascade within the anterior segment of the eye thus preserving the visual axis following infection will require intervention at multiple levels simultaneously targeting a number of non-redundant cytokines, chemokines, and other soluble factors that influence the recruitment of leukocytes to the cornea as well as hem- and lymph-angiogenesis. Deciphering the early events following infection continues to be a necessary but arduous task for the eventual development of reagents to replace or complement current anti-inflammatory steroids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory compounds for use not only in the eye but other critical organs (e.g., brain).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Gabby Nguyen for her expert technical assistance in the phenotypic analysis of infiltrating cells. The authors are grateful to Dr. Bao Lu who provided the CXCR3 −/− breeder mice to establish the colony at OUHSC. This work was supported by a grant from The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH, AI067309, Research to Prevent Blindness (RPB) Jules and Doris Stein Research Professorship award, and an unrestricted grant from RPB.

Contributor Information

Daniel J.J. Carr, Email: dan-carr@ouhsc.edu.

Todd Wuest, Email: todd-wuest@ouhsc.edu.

John Ash, Email: john-ash@ouhsc.edu.

References

- 1.Thomas J, Gangappa S, Kanangat S, Rouse BT. On the essential involvement of neutrophils in the immunopathologic disease: herpetic stromal keratitis. J Immunol. 1997;158:1383–1391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Su YH, Yan X-T, Oakes JE, Lausch RN. Protective antibody therapy is associated with reduced chemokine transcripts in herpes simplex virus type 1 corneal infection. J Virol. 1996;70:1277–1281. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1277-1281.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carr DJJ, Chodosh J, Ash J, Lane TE. Effect of anti-CXCL10 monoclonal antibody on herpes simplex virus type 1 keratitis and retinal infection. J Virol. 2003;77:10037–10046. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.18.10037-10046.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wickham S, Ash J, Lane TE, Carr DJJ. Consequences of CXCL10 and IL-6 induction by the murine IFN-α1 transgene in ocular herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. Immunologic Res. 2004;30:191–200. doi: 10.1385/IR:30:2:191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonecchi R, Bianchi G, Bordignon PP, D’Ambrosio D, Lang R, Borsatti A, Sozzani S, Allavena P, Gray PA, Mantovani A, Sinigaglia F. Differential expression of chemokine receptors and chemotactic receptor responsiveness of type 1 T helper cells (Th1s) and Th2s. J Exp Med. 1998;187:129–134. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.1.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qin S, Rottman JB, Myers P, Kassam N, Weinblatt M, Loetscher M, Koch AE, Moser B, Mackay CR. The chemokine receptors CXCR3 and CCR5 mark subsets of T cells associated with certain inflammatory reactions. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:746–754. doi: 10.1172/JCI1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kohrgruber N, Gröger M, Meraner P, Kriehuber E, Petzelbauer P, Brandt S, Stingl G, Rot A, Maurer D. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell recruitment by immobilized CXCR3 ligands. J Immunol. 2004;173:6592–6602. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.11.6592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kadowaki N, Antonenko S, Lau JY, Liu YJ. Natural interferon α/β-producing cells link innate and adaptive immunity. J Exp Med. 2000;192:219–226. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cantin E, Tanamachi B, Openshaw H, Mann J, Clarke K. Gamma interferon (IFN- γ) receptor null-mutant mice are more susceptible to herpes simplex virus type 1 infection than IFN- γ ligand null-mutant mice. J Virol. 1999;73:5196–5200. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.6.5196-5200.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lekstrom-Himes JA, LeBlanc RA, Pesnicak L, Godleski M, Straus SE. Gamma interferon impedes the establishment of herpes simplex virus type 1 latent infection but has no impact on its maintenance or reactivation in mice. J Virol. 2000;74:6680–6683. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.14.6680-6683.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ikemoto K, Pollard RB, Fukumoto T, Morimatsu M, Suzuki F. Small amounts of exogenous IL-4 increase the severity of encephalitis induced in mice by the intranasal infection of herpes simplex virus type 1. J Immunol. 1995;155:1326–1333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daheshia M, Kuklin N, Kanangat S, Manickan E, Rouse BT. Suppression of ongoing ocular inflammatory disease by topical administration of plasmid DNA encoding IL–10. J Immunol. 1997;159:1945–1952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghiasi H, Cai S, Slanina SM, Perng G-C, Nesburn AB, Wechsler SL. The role of interleukin (IL)-2 and IL-4 in herpes simplex virus type 1 ocular replication and eye disease. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:1086–1093. doi: 10.1086/314736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halford WP, Gebhardt BM, Carr DJJ. Persistent cytokine expression in the trigeminal ganglion latently infected with herpes simplex virus type 1. J Immunol. 1996;157:3542–3549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wareing MD, Lyon AB, Lu B, Gerard C, Sarawar SR. Chemokine expression during development and resolution of a pulmonary leukocyte response to influenza A virus infection in mice. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76:886–895. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1203644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng M, Klinman DM, Gierynska M, Rouse BT. DNA containing CpG motifs induces angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:8944–8949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132605599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hemmi H, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Sato S, Sanjo H, Matsumoto M, Hoshino K, Wagner H, Takeda K, Akira S. A Toll-like receptor recognizes bacterial DNA. Nature. 2000;408:740–745. doi: 10.1038/35047123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wuest T, Austin BA, Uematsu S, Thapa M, Akira S, Carr DJJ. Intact TLR 9 and type I interferon signaling pathways are required to augment HSV-1 induced corneal CXCL9 and CXCL10. J Neuroimmunol. 2006;179:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carr DJJ, Campbell IL. Herpes simplex virus type 1 induction of chemokine production is unrelated to viral load in the cornea but not in the nervous system. Viral Immunol. 2006;19:741–746. doi: 10.1089/vim.2006.19.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carr DJJ, Ash J, Lane TE, Kuziel WA. Abnormal immune response of CCR5-deficient mice to ocular infection with herpes simplex virus type 1. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:489–499. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81339-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glass WG, Lane TE. Functional expression of chemokine receptor CCR5 on CD4+ T cells during virus-induced central nervous system disease. J Virol. 2003;77:191–198. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.1.191-198.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsieh M-F, Lai S-L, Chen J-P, Sung J-M, Lin Y-L, Wu-Hsieh BA, Gerard C, Luster A, Liao F. Both CXCR3 and CXCL10/IFN-inducible protein 10 are required for resistance to primary infection by dengue virus. J Immunol. 2006;177:1855–1863. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stiles LN, Hardison JL, Schaumburg CS, Whitman LM, Lane TE. T cell antiviral effector function is not dependent on CXCL10 following murine coronavirus infection. J Immunol. 2006;177:8372–8380. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.12.8372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stiles LN, Hosking MP, Edwards RA, Strieter RM, Lane TE. Differential roles for CXCR3 in CD4+ and CD8+ T cell trafficking following viral infection of the CNS. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:613–622. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wickham S, Lu B, Ash J, Carr DJJ. Chemokine receptor deficiency is associated with increased chemokine expression in the peripheral and central nervous systems and increased resistance to herpetic encephalitis. J Neuroimmunol. 2005;162:51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tamesis RR, Messmer EM, Rice BA, Dutt JE, Foster SC. The role of natural killer cells in the development of herpes simplex virus type 1 induced stromal keratitis in mice. Eye. 1994;8:298–306. doi: 10.1038/eye.1994.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghiasi H, Cai S, Perng GC, Nesburn AB, Wechsler SL. The role of natural killer cells in protection of mice against death and corneal scarring following ocular HSV-1 infection. Antiviral Res. 2000;45:33–45. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(99)00075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halford WP, Maender JL, Gebhardt BM. Re-evaluating the role of natural killer cells in innate resistance to herpes simplex virus type I. Virol J. 2005;2:56. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-2-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stuart PM, Summers B, Morris JE, Morrison LA, Leib DA. CD8+ T cells control corneal disease following ocular infection with herpes simplex virus type 1. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:2055–2063. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lepisto AJ, Frank GM, Xu M, Stuart PM, Hendricks RL. CD8 T cells mediate transient herpes stromal keratitis in CD4-deficient mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:3400–3409. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wuest T, Farber J, Luster A, Carr DJJ. CD4+ T cell migration into the cornea is reduced in CXCL9 but not CXCL10 deficient mice following herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. Cell Immunol. 2006;243:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clark-Lewis I, Mattioli L, Gong JH, Loetscher P. Structure-function relationship between the human chemokine receptor CXCR3 and its ligands. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:289–295. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209470200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allen S, Crown S, Handel T. Chemokine:Receptor structure, interactions, and antagonism. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:787–820. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]