Abstract

Pathogenic α-synuclein (αS) gene mutations occur in rare familial Parkinson’s disease (PD) kindreds, and wild-type αS is a major component of Lewy bodies (LBs) in sporadic PD, dementia with LBs (DLB), and the LB variant of Alzheimer’s disease, but β-synuclein (βS) and γ-synuclein (γS) have not yet been implicated in neurological disorders. Here we show that in PD and DLB, but not normal brains, antibodies to αS and βS reveal novel presynaptic axon terminal pathology in the hippocampal dentate, hilar, and CA2/3 regions, whereas antibodies to γS detect previously unrecognized axonal spheroid-like lesions in the hippocampal dentate molecular layer. The aggregation of other synaptic proteins and synaptic vesicle-like structures in the αS- and βS-labeled hilar dystrophic neurites suggests that synaptic dysfunction may result from these lesions. Our findings broaden the concept of neurodegenerative “synucleinopathies” by implicating βS and γS, in addition to αS, in the onset/progression of PD and DLB.

Keywords: perforant pathway, mossy fibers

The synucleins are a family of soluble presynaptic proteins that are abundant in neurons and include α-synuclein (αS) (also known as the nonamyloid component of plaques precursor protein or NACP) (1, 2), β-synuclein (βS) (also known as phosphoneuroprotein 14 or PNP14) (3, 4), and γ-synuclein (γS) (also known as breast cancer-specific gene 1 or BCSG1 and persyn) (5, 6). Although they are homologous, each synuclein is encoded by a different gene on chromosomes 4q21.3-q22 (αS) (7, 8), 5q35 (βS) (9), and 10q23 (γS) (10).

The functions of synucleins are poorly understood; however, mutations in the αS gene are linked to familial Parkinson’s disease (PD) in rare kindreds (11, 12). αS is a major component of Lewy bodies (LBs) and Lewy neurites in sporadic PD, dementia with LBs (DLB) and a subtype of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) with abundant neocortical LBs known as the LB variant of AD (13–15). Further, LBs have been described in familial AD caused by presenilin and amyloid precursor protein gene mutations (16) and Down’s syndrome (17). In addition, αS is a major component of glial cytoplasmic inclusions (GCIs) in multiple system atrophy (MSA) (18, 19) as well as the neuronal inclusions and GCIs in Hallervorden-Spatz disease (18). Heretofore, βS and γS have not been implicated in neurodegenerative disease (15, 18), although γS may play a role in breast cancer progression (5).

Here, we report the identification of axonal pathology with antibodies to βS and γS in the hippocampus of PD and DLB brains, but not in control brains, thereby implicating βS and γS, in addition to αS, in neurodegenerative disease.

Methods

Case Materials.

Brains of autopsy proven PD (n = 5), DLB (n = 5), AD (n = 5), MSA (n = 2), Pick’s disease (n = 2), and normal controls (n = 5) were examined and compared after postmortem assessment in the Center for Neurodegenerative Disease Research at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine to establish a neuropathological diagnosis in each case (15–18, 20).

Immunohistochemistry.

Immunohistochemistry was performed on 6-μm thick serial sections of paraffin-embedded blocks of hippocampus from brains fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, Bouin’s solution, or 70% ethanol/150 mM NaCl as described (15, 18, 20). Briefly, sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated, and alternate sections were treated with 88% formic acid for 1 min followed by a wash in distilled water for 5 min. After treatment with methanol/H2O2, sections were immersed in Tris-buffered saline (TBS), pH 7.4, blocked in TBS/0.08% Triton X-100/2% horse serum and incubated overnight at 4°C with antibodies to: αS (LB509 and Syn208; refs. 15 and 18), βS (Syn207; ref. 18), γS (antisera 20; ref. 18), ubiquitin (1510, Chemicon; ref. 21), synaptophysin (SY38, Boehringer Mannheim; ref. 22), synapsin I (Molecular Probes; ref. 23), and synaptobrevin (MAB335, Boehringer Mannheim; ref. 24). Sections were developed by using the avidin-biotin complex method (Vector Laboratories) with diaminobenzidine as the chromogen and evaluated, and then images of regions of interest in the sections were captured with a Nikon X-100 microscope and imported into Northern Exposure (Empix, Glen Mills, PA). Double-label immunofluorescence studies were performed with species-specific anti-Ig antibodies conjugated to FITC and Texas red fluorochromes (Jackson ImmunoResearch) as described (15, 18, 20).

Electron Microscopy.

Electron microscopy was performed on DLB brain as described (15, 16, 18). Briefly, small blocks of hippocampus were removed from three frozen DLB brains and immersed immediately in a phosphate-buffered (pH 7.4) solution containing 0.1% glutaraldehyde and 4% paraformaldehyde for fixation overnight. The blocks were sectioned at 50 μm and probed with antibodies to αS and γS to identify immunoreactive structures by light microscopy for pre-embedding immuno-electron microscopy. To do this, sections were washed in PBS, blocked with 2% horse serum, and incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C after which they were washed with PBS, incubated with biotinylated anti-mouse IgG (Vector Laboratories) for 1 hr, washed again, and then developed by using the avidin-biotin complex method (Vector Laboratories) with diaminobenzidine as a chromogen. Adjacent sections were further processed with a silver enhancement procedure as described (25). Control sections were processed in parallel with the exception of the primary antibody. Sections were dehydrated and embedded in epoxy resin. Ultrathin sections were prepared and viewed as described (15, 16, 18).

Similar samples also were examined by postembedding immuno-electron microscopic methods. Briefly, 50-μm thick sections were washed with PBS, dehydrated, and embedded with LR white (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Fort Washington, PA). Ultrathin sections were cut, blocked with horse serum, incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight, then washed in PBS and incubated with anti-mouse IgG conjugated with 10-nm gold particles (Electron Microscopy Sciences). After light staining with uranyl acetate (Electron Microscopy Sciences), the immunogold-labeled structures were examined as described (15, 16, 18).

Results

Light Microscopy of Synuclein Pathology in PD And DLB Hippocampus.

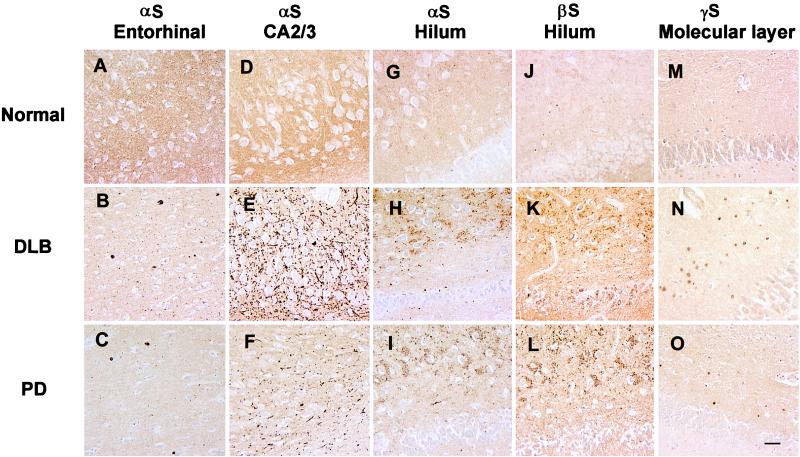

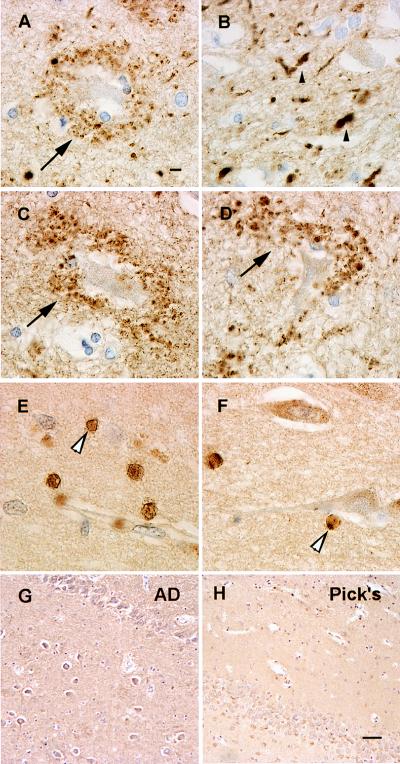

Consistent with previous reports (13, 15), αS immunoreactivity in the normal hippocampus was homogeneously distributed throughout the neuropil (Fig. 1 A, D, G, J, and M), and the most striking hippocampal lesions were abundant αS-positive Lewy neurites in the CA2/3 region in all PD and DLB cases (Fig. 1 E and F), in addition to αS-positive LBs in entorhinal cortex (Fig. 1 B and C). However, these lesions were not seen in control cases (Table 1) even when αS immunoreactivity was greatly enhanced by pretreating sections with formic acid (26). In addition, many hilar neurons in both PD and DLB cases were surrounded by accumulations of αS-positive punctate or vesicular profiles (Figs. 1 H and I and 2A). This pathology was not seen in normal control (Fig. 1G) and AD brains (Table 1), nor was it seen in the MSA or Pick’s disease cases (Table 1). Notably, the marked abundance and variable size of these profiles in the PD and DLB brains suggest that they reflect pathological aggregates of αS in axon terminals of dentate mossy fiber projections to hilar neurons. The abundance of these vesicles appeared to parallel that of αS-positive LBs in entorhinal cortex and Lewy neurites in the CA2/3 regions of the PD and DLB cases (Figs. 1 and 2). Notably, these vesicles were βS-positive but γS-negative (Figs. 1 K and L and 2 C and D) in PD and DLB brains, but they were not detected in normal control (Fig. 1J) or AD brains (Fig. 2G). However, axonal spheroid-like lesions were identified in the stratum moleculare of the dentate gyrus of PD and DLB cases with antibodies to γS, but not with anti-αS or anti-βS antibodies (Figs. 1 N and O and 2 E and F). These axonal spheroids were most apparent after pretreatment with formic acid; otherwise, they were difficult to distinguish from normal neuropil staining. Although similar γS-positive spheroids were seen in the CA1 region, they were most abundant in the PD and DLB dentate molecular layer (Fig. 2 E and F), but they were not seen in controls (Fig. 1M), Pick’s disease (Fig. 2H), AD, or MSA (Table 1). To determine whether other synaptic proteins were present in these lesions, we performed immunohistochemical studies that showed accumulations of synapsin, synaptophysin, and synaptobrevin in the hilar vesicular profiles, suggesting that these pathologically altered axon terminals or their corresponding synapses may be dysfunctional (Fig. 3 A–C). The γS-positive spheroids in the dentate molecular layer may be a site of more proximal axonal pathology, and they were positive only with antibodies to synaptobrevin and not to the other synaptic proteins (Fig. 3D). Double-label immunofluorescence studies demonstrated colocalization of synaptobrevin and synaptophysin with αS (Fig. 3 E–G) and γS (Fig. 3 H–J). Finally, although other regions of PD and DLB brains (e.g., substantia nigra, striatum) contained αS-positive LBs and dystrophic Lewy neurites, none of these regions showed degenerating axon terminals similar to those described above in the hippocampus (data not shown).

Figure 1.

This series of low-power images depicts αS, βS, and γS immunoreactivity in hippocampus and entorhinal cortex of normal control (Top), DLB (Middle), and PD (Bottom) brains. The first column demonstrates the normal αS neuropil staining pattern (A) compared with the DLB (B) and PD (C) entorhinal cortex with αS-positive LBs using the LB509 antibody to αS. The second column shows the normal αS neuropil staining pattern (D) and dystrophic Lewy neurites in the CA2/3 region of hippocampus in the DLB case (E) and to a lesser extent in PD (F) by using LB509. The third column shows the normal αS neuropil staining pattern (G) and degenerate mossy fiber terminals around hilar neurons in DLB (H) and PD (I) by using LB509. The fourth column shows the normal αS neuropil staining pattern (J) as well as degenerate mossy fibers in DLB (K) and PD (L) by using the Syn207 antibody to βS. The final column shows the normal αS neuropil staining pattern (M) and depicts degenerate terminals in the stratum moleculare of the dentate gyrus in DLB (N) and PD (O) by using antisera 20 to γS. All panels are at the same magnification, and the scale bar in O = 20 μm.

Table 1.

Synuclein-immunoreactive hippocampal pathology in neurodegenerative disorders

| Diagnosis | Total cases | αS

|

βS | γS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LBs | Mossy fiber | Other* | ||||

| PD | 5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 0/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| DLB | 5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 0/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| Normal | 5 | 0/5 | 2/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 |

| AD | 5 | 0/5 | 2/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 |

| Pick’s | 2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 2/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 |

| MSA | 2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 2/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 |

αS, βS, and γS pathology was consistently seen in all PD and DLB cases. In normal and AD cases, no LBs or Lewy neurites were seen; however, a few hilar neurons demonstrated αS immunoreactivity suggestive of degenerating axon terminals. This immunoreactivity was similar, though substantially reduced, when compared to the LB disorders. No βS or γS pathology was noted in the normal or AD cases. The Pick’s disease cases demonstrated Pick bodies immunoreactive for αS in the dentate and parahippocampal gyrus; however, no degenerating axon terminals were seen. No βS or γS pathology was noted. In the MSA cases, multiple GCIs immunoreactive for αS were noted in the white matter of the hippocampus; however, few degenerating axon terminals were noted. No βS or γS pathology was seen.

*Non-LB pathology.

Figure 2.

This series of higher-power images depicts degenerate terminals labeled with antibodies to αS, βS, and γS in PD (A, G, and E) and DLB (B, D, and F) compared with AD (G) and Pick’s disease (H) where these lesions are not seen. (A) Degenerate mossy fiber terminals surrounding a hilar neuron with LB509 (arrow). (B) Lewy neurites and degenerate terminals on CA2/3 neurons (small arrowhead) with LB509. (C and D) Degenerating mossy fibers terminating on hilar neurons (arrow) with Syn207. (E) A high-power view of the γS immunoreactive terminals (large arrowheads) in the stratum moleculare of the dentate gyrus. (F) γS pathology in the CA1 region of the hippocampus (large arrowhead). (G) The absence of βS hilar pathology in AD. (H) Absence of γS pathology in Pick’s disease. A-F are at the same magnification (scale bar in A = 5 μm), and G and H are at the same magnification (scale bar in H = 20 μm).

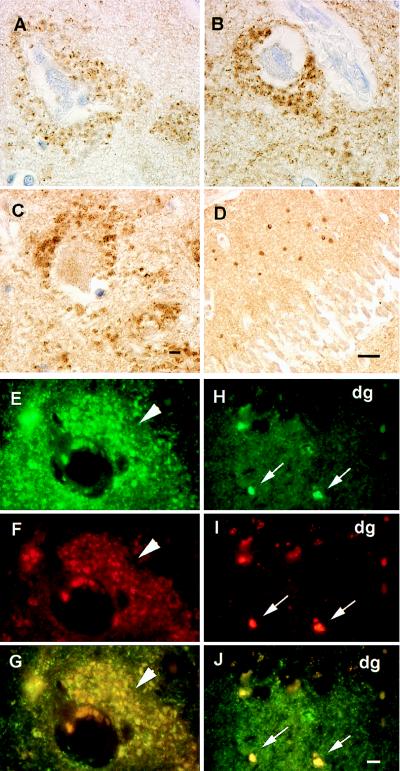

Figure 3.

Shown are degenerating mossy fiber terminals in PD and DLB cases with the presynaptic proteins synapsin, synaptophysin, and synaptobrevin. Degenerate mossy fiber terminals are labeled with antibodies against synapsin (A), synaptophysin (B), and synaptobrevin (C) identical to pathology seen with antibodies to αS and βS. (D) Degenerate terminals in the stratum moleculare stained by antibody against synaptobrevin similar to that seen with antisera 20 (γS). (E–G) Double-label immunofluorescence of αS (green channel only in E) and synaptophysin (red channel only in F) terminals surrounding a hilar neuron (arrowheads), which colocalize to the same profiles in G (yellow immunofluorescence). (H–J) Double label immunofluorescence of γS (green channel only in H), synaptobrevin (red channel only in I), and their colocalization in J (yellow immunofluorescence identified by small arrows) in the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus (dg). A–C and E–J are at the same magnification (scale bars in C and J = 5 μm). In D the scale bar = 20 μm.

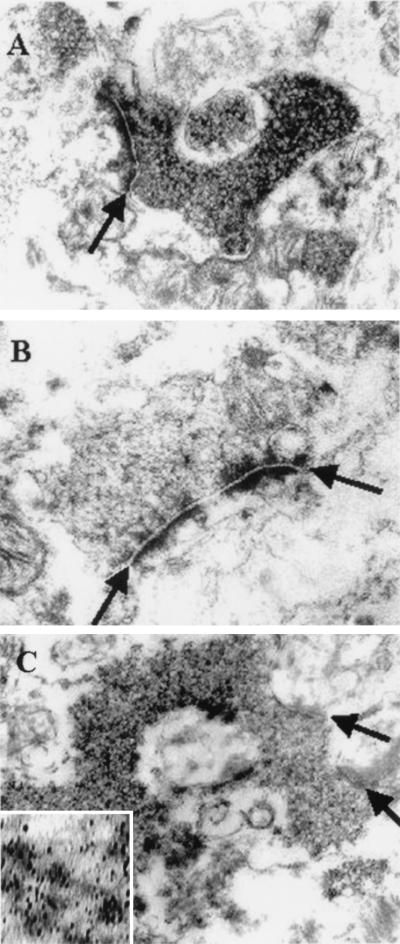

Electron Microscopy of Synuclein Pathology in PD and DLB Hippocampus.

Pre-embedding methods revealed that αS was localized to various neuronal processes (with and without myelin sheaths) and to terminal complexes of mossy fiber rosettes. The rosettes appeared to be predominantly surrounding the hilar neurons as identified by light microscopy (Fig. 2A). The αS immunoreactivity appeared to be greatest on the vesicle-like structures densely accumulated within presynaptic axon terminals (Fig. 4 A and B). This pathology also was demonstrated with silver-enhancement methods (Fig. 4C), and some filament bundles were associated with the vesicle-like structures in the terminal segments of axons (data not shown). The morphology of the αS-immunoreactive vesicles is shown in a higher-power photomicrograph (Fig. 4C Inset), although, as expected with autopsy brain, the preservation of vesicular membranes was not optimal.

Figure 4.

The electron microscopic appearance of degenerate mossy fiber terminals. (A) The accumulation of αS immunoreactive vesicles in the presynaptic terminal of a mossy fiber rosette. (B) A control of a similar representative view without diaminobenzidine. (C) The αS immunoreactive vesicles demonstrated with silver enhancement technique. (Inset) A higher magnification of the αS immunoreactive synaptic vesicle. Arrows demonstrate synaptic clefts. Magnifications: ×45,000 for A–C; ×96,000 for Inset in C.

Discussion

The abnormal aggregation of proteins into fibrillar lesions is a neuropathological hallmark of several sporadic and inherited neurodegenerative diseases (27). For example, LBs appear to be composed primarily of αS, but other proteins, including neurofilament subunits, are present in many LBs (20, 27–29). Although LBs are hallmark lesions of PD, they also are the predominant cortical lesions of DLB, and they define the most common subtype of sporadic AD, i.e., the LB variant (27–30). In addition, αS is a major component of the GCIs of MSA (18, 19), and antibodies to αS reveal LBs in the brains of more familial AD (16) and Down’s syndrome (17) patients than previously reported. Five familial PD kindreds were reported to have missense mutations in the αS gene (11, 12), but the majority of familial PD kindreds do not have αS gene mutations, whereas PD and DLB are predominantly sporadic (31–34).

Although βS and γS are abundant in brain, they have not been implicated previously in any neurological disease. Thus, the present study is significant because it describes brain abnormalities in a neurodegenerative disease (i.e., PD and DLB) that contain pathological accumulations of βS and γS. Accordingly, we conclude that βS and γS, in addition to αS, may play mechanistic roles in the onset and progression of several neurodegenerative disorders. Indeed, because αS pathology may be seen in other neurodegenerative diseases and in a few normal controls (see Table 1), βS and γS pathology may be more specific to LB disorders.

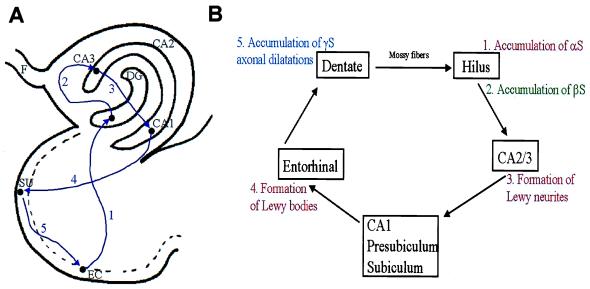

Because the αS- and βS-positive lesions appear to be predominantly localized to abnormal aggregates in the mossy fiber terminals that synapse on hilar neurons, and the neuritic pathology labeled by antibodies to αS is most likely in axon terminals of CA2/3, these abnormal processes may impair synaptic transmission in hippocampal perforant pathway projections critical to memory and behavior as schematically illustrated in Fig. 5 (35). Indeed, this notion is supported by studies of the effects of botulinum toxin on the presynaptic terminals of the giant squid (36). This resulted in a 3-fold increase in the vesicular content of presynaptic terminals by interfering with the docking and/or fusion properties of the synaptic proteins (i.e., synaptophysin, synaptobrevin, and synapsin I) and blocking the release of vesicles as well as their neurotransmitter contents (36–38). This toxin-induced accumulation of synaptic vesicles resembles that described in Fig. 4. Thus, the aggregation of synuclein-labeled vesicles and filaments in presynaptic terminals might reflect impaired synaptic vesicle release and synaptic dysfunction (36). Similar impairments also could result from the γS pathology localized to the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus (see Fig. 5), which resembles pathology detected in frontotemporal dementias by using antibodies to synaptophysin (39). Notably, whereas LBs and Lewy neurites were recognized with antibodies to ubiquitin (40, 41), none of the pathological synaptic lesions described here were labeled by antiubiquitin antibodies. As illustrated in Fig. 5, the addition of γS pathology in the molecular layer demonstrates that all components of the perforant pathway (35) are affected by aggregation of synuclein proteins. The absence of the degenerating axon terminals in other regions of the PD and DLB brain suggests that this pathology is specific to hippocampal projections.

Figure 5.

Perforant pathway and synuclein pathology. (A) The components of the hippocampal perforant pathway that play a critical role in behavior and memory. Neurons in entorhinal cortex send information in a unidirectional manner to dendrites in the molecular layer of neurons dentate gyrus (at 1), followed by hilar and CA2/3 neurons (at 2), and then to neurons in CA1 and presubicular (at 3) regions of the hippocampus. CA1 neurons then project back to the subiculum (at 4) and then to the entorhinal cortex (at 5) to complete this loop of interconnected neurons. (B) The perforant pathway in schematic form to illustrate the involvement of αS, βS, and γS pathology throughout this critical pathway in the PD and DLB hippocampus where synaptic transmission might be impaired by one or more synuclein lesions. EC, entorhinal cortex; SU, subiculum; DG, dentate gyrus; F, fornix.

The function of the synucleins is poorly understood but they are soluble presynaptic proteins that may play a role in synaptic transmission. However, αS becomes less soluble in neurodegenerative disease, which may lead to the formation of fibrillar aggregates (15, 18) in the form of LBs and GCIs. Significantly, the hippocampal αS pathology appears to localize primarily on vesicular structures in the mossy fiber axon terminals but also may aggregate as filamentous structures. The hippocampal synuclein pathology described here also may contain insoluble βS and γS because it was seen better after pretreatment with formic acid, which is known to enhance αS immunoreactivity (26). Moreover, the observation that the pathology in the hilus and dentate gyrus also contains the synaptic proteins synapsin, synaptophysin, and synaptobrevin (37, 38) suggests that these lesions are degenerating presynaptic terminals.

Although it is unknown whether the transformation of normal soluble synuclein proteins into insoluble pathological proteins that form aggregates (e.g., LBs) causes neurodegenerative diseases, it seems increasingly likely that these events compromise the function and viability of neurons. For example, LB-containing neurons could undergo a “dying back” phenomenon caused by blocked axonal transport, disconnecting one cortical region from another (20, 27, 28). Likewise, the accumulation of synuclein proteins in the degenerating terminals described here could interfere with the unidirectional flow of information in the hippocampus (see Fig. 5), which is an important component of the neuroanatomical circuits involved in memory and behavior (35). Thus, efforts to further elucidate the pathobiology of the synuclein proteins are likely to lead to improved strategies for the development of novel therapeutic interventions for PD, DLB, the LB variant of AD, and other synucleinopathies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Danielle Lavalla and Ms. Theresa Schuck for their expert technical assistance. This project was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association.

Abbreviations

- LB

Lewy body

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- DLB

dementia with LBs

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- αS

α-synuclein

- βS

β-synuclein

- γS

γ-synuclein

- MSA

multiple system atrophy

- GCI

glial cytoplasmic inclusion

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Ueda K, Fukushima H, Maliah E, Xia Y, Iwai A, Yoshimoto M, Otero D A, Kondo J, Ihara Y, Saitoh T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11282–11286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jakes R, Spillantini M G, Goedert M. FEBS Lett. 1994;345:27–32. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00395-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tobe T, Nakajo S, Tanaka A, Mitoya A, Omata K, Nakaya K, Tomita M, Nakmura Y. J Neurochem. 1992;59:1624–1629. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb10991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakajo S, Tsukada K, Omata K, Nakamura Y, Nakaya K. Eur J Biochem. 1993;217:1057–1063. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ji H, Liu Y E, Jia T, Wang M, Liu J, Xiao G, Joseph B K, Rosen C, Shi Y E. Cancer Res. 1997;57:759–764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ninkina N N, Alimova-Kost M V, Paterson J W, Delaney L, Cohen B B, Imreh S, Gnuchev N V, Davies A M, Buchman V L. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1417–1424. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.9.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campion D, Martin C, Helig R, Charbonnier F, Moreau V, Flaman J M, Petit J L, Hannequin D, Brice A, Frebourg T. Genomics. 1995;26:254–257. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(95)80208-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen X, de Silva H A, Pettenati M J, Rao P N, St. George-Hyslop P, Roses A D, Xia Y, Horsburgh K, Ueda K, Saitoh T. Genomics. 1995;26:425–427. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(95)80237-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spillantini M G, Divane A, Goedert M. Genomics. 1995;27:379–381. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lavedan C, Leroy E, Dehejia A, Buchholtz S, Dutra A, Nussbaum R L, Polymeropoulos M H. Hum Genet. 1998;103:106–112. doi: 10.1007/s004390050792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Polymeropoulos M H, Lavedan C, Leroy E, Ide S E, Dehejia A, Dutra A, Pike B, Root H, Rubenstein J, Boyer R, et al. Science. 1997;276:2045–2047. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kruger R, Kuhn W, Muller T, Woitalla D, Graeber M, Kosel S, Przuntek H, Epplen J T, Schols L, Riess O. Nat Genet. 1998;18:106–108. doi: 10.1038/ng0298-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spillantini M G, Schmidt M L, Lee V M-Y, Trojanowski J Q, Jakes R, Goedert M. Nature (London) 1997;388:839–840. doi: 10.1038/42166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wakabayashi K, Matsumoto K, Takayama K, Yoshimoto M, Takahashi H. Neurosci Lett. 1997;239:45–48. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00891-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baba M, Nakajo S, Tu P H, Tomita T, Nakaya K, Lee V M-Y, Trojanowski J Q, Iwatsubo T. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:879–884. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lippa C F, Fujiwara H, Mann D M A, Giasson B, Baba M, Schmidt M L, Nee L E, O’Connell B, Pollen D A, St. George-Hyslop P, et al. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:1365–1370. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65722-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lippa C F, Schmidt M L, Lee V M-Y, Trojanowski J Q. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:353–357. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199903)45:3<353::aid-ana11>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tu P H, Galvin J E, Baba M, Giasson B, Tomita T, Leight S, Nakajo S, Iwatsubo T, Trojanowski J Q, Lee V M-Y. Ann Neurol. 1998;44:415–422. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wakabayashi K, Yoshimoto M, Tsuji S, Takahashi H. Neurosci Lett. 1998;249:180–182. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00407-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galvin J E, Lee V M-Y, Baba M, Mann D M A, Dickson D W, Yamaguchi H, Schmidt M L, Iwatsubo T, Trojanowski J Q. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:595–603. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaw G, Chau V. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2854–2858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wiedenmann B, Franke W W. Cell. 1985;41:1017–1028. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Navone F, Greengard R, De Camilli P. Science. 1984;226:1209–1211. doi: 10.1126/science.6438799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Honer W G, Hu L, Davies P. Brain Res. 1993;609:9–20. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90848-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodriguez E M, Yulis R, Peruzzo B, Alvial G, Andrade R. Histochemistry. 1984;81:253–263. doi: 10.1007/BF00495636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takeda A, Hashimoto M, Mallory M, Sundsumo M, Hansen L, Sisk A, Masliah E. Lab Invest. 1998;78:1169–1177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trojanowski J Q, Goedert M, Iwatsubo T, Lee V M-Y. Cell Death Differ. 1998;5:832–837. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galvin J E, Lee V M-Y, Schmidt M L, Tu P H, Iwatsubo T, Trojanowski J Q. In: Advances in Neurology. Stern G, editor. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1999. pp. 313–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pollanen M S, Dickson D W, Bergeron C. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1993;52:183–191. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199305000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McKeith I G, Galasko D, Kosaka K, Perry E K, Dickson D W, Hansen L A, Salmon D P, Lowe J, Mirra S S, Byrne E J, et al. Neurology. 1996;47:1113–1124. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.5.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chan P, Jiang X, Forno L S, Di Monte D A, Tanner C M, Langston J W. Neurology. 1998;50:1136–1137. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.4.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farrer M, Wavrant-De Vrieze F, Crook R, Boles L, Perez-Tur J, Hardy J, Johnson W G, Steele J, Maraganore D, Gwinn K, Lynch T. Ann Neurol. 1998;43:394–397. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vaughan J R, Farrer M, Wszolek Z K, Gasser T, Durr A, Agid Y, Bonifati V, DeMichele G, Volpe G, Lincoln S, et al. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:751–753. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.4.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zareparsi S, Kay J, Camicoli R, Kramer P, Nutt J, Bird T, Litt M, Payami H. Lancet. 1998;351:37–38. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)78089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Amaral D G, Insausti R. In: The Human Nervous System. Paxinos G, editor. New York: Academic; 1990. pp. 711–755. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marsal J, Ruiz-Mantasell B, Blasi J, Moreira J E, Contreras D, Sugimori M, Llinas R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;9:14871–14876. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sudhof T C. Nature (London) 1995;375:645–653. doi: 10.1038/375645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Volknandt W. Neuroscience. 1995;64:277–300. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00408-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou L, Miller B L, McDaniel C H, Kelly L, Kim O J, Miller C A. Ann Neurol. 1998;44:99–109. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dickson D W, Ruan D, Crystal H, Mark M H, Davies P, Kress Y, Yen S H. Neurology. 1991;41:1402–1409. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.9.1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dickson D W, Schmidt M L, Lee V M-Y, Zhao M-L, Yen S-H, Trojanowski J Q. Acta Neuropathol. 1994;87:269–276. doi: 10.1007/BF00296742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]