Abstract

Objective

To evaluate clinically useful measures of Beta-cell function derived from the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) or mixed meal (Boost) tolerance test to assess insulin secretion, in comparison with the gold standard method of the hyperglycemic clamp (Hyper-C).

Study design

We hypothesized that OGTT/Boost derived measures are useful estimates of β-cell function and correlate well with insulin secretion measured during the Hyper-C. We assessed the correlation between the ratio of the early incremental insulin/glucose responses at 15 and 30 min (ΔI15/ΔG15, ΔI30/ΔG30) of the OGTT and Boost, with insulin secretion during the Hyper-C (225 mg/dl). The same indices were evaluated using C-peptide (C). 26 (14M/12F) children (9.9±0.2yrs, BMI:22.1±1.2kg/m2) underwent a 2 hour Hyper-C (225 mg/dl) and a 3 hour OGTT and Boost with measurements of glucose (G), insulin (I) and C.

Results

Correlations between clamp- and OGTT-derived measures of insulin secretion were stronger for the 15 minute than the 30 minute indices of insulin secretion and stronger with the use of C-peptide than insulin levels (r = 0.7, p < 0.001 for 1st phase C-peptide vs both OGTT and Boost ΔC15/ΔG15 ).

Conclusion

In youth with normal glucose tolerance, C-peptide rather than insulin at 15 minutes of the OGTT and/or Boost provides a reliable estimate of β-cell function that correlates well with clamp derived insulin secretion.

Keywords: OGTT, Boost test, Insulinogenic index, C-peptide, insulin clearance

Obesity, impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), and type 2 diabetes are characterized with insulin resistance, in addition to impaired insulin secretion in the latter two (1). With the increasing rates of obesity (2,3), IGT, and type 2 diabetes in youth (4), simple, clinically obtainable measures of insulin secretion are desirable for the follow-up of progression from one stage to the other and for evaluation of therapeutic interventions. The oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) is recommended by the WHO and the ADA for the diagnosis of IGT and diabetes and is a frequently utilized clinical tool. The objective of our study was to evaluate if measures of insulin release derived form the OGTT or a mixed meal (Boost) test correlate with insulin secretion derived from the hyperglycemic clamp in children.

We hypothesized that OGTT or mixed meal (Boost) derived measures of insulin release are useful estimates of β-cell function, and correlate well with insulin secretion measured during the hyperglycemic clamp (Hyper-C).

METHODS

The study population consisted of 26 (14M/12F) children, 7 to 12 years of age (mean 9.9±1.1 years). They included 15 African American and 11 Caucasian normoglycemic children (HbA1C: 5.2±0.4%), 13 normal weight (NW) and 13 overweight or at risk for overweight (OW) (BMI>85th %) with a mean BMI of 22.2 ± 6.1 kg/m2 , mean % body fat of 27.5 ± 13.6 % and fat mass 13.2 ± 10.6 kg. Some of these children were previously reported (5). All studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pittsburgh. Children were recruited through newspaper advertisement and through flyers posted in the health center. All research participants and their parents or guardians gave informed consent/ assent after detailed explanation of the research study. All subjects were documented to be in good health by a thorough medical interview and physical examination. Overweight children were free of any associated comorbidities or syndromes leading to obesity. Subjects were not receiving any medications. Subjects were assessed to be in Tanner stage 1 puberty by careful physical examination.

After an overnight fast of 10 to 12 hours, subjects were studied in the Pediatric Clinical and Translational Research Center (PCTRC) of Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh on 2 separate occasions, 1 to 2 weeks apart. Randomly, the children underwent a 3-hour oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) (1.75 g/kg, max 75 g) and a mixed meal test (Boost) (55% carbohydrate, 25% protein and 20% fat). Blood samples were drawn at 0, 15, 30, 60, 90, 120, and 180 minutes for determination of glucose (G), insulin (I), and C-peptide (C) levels. They also underwent a 2-hour hyperglycemic clamp (Hyper-C) (225 mg/dl) to measure in-vivo insulin secretion.

Body composition was assessed by dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) using a Lunar (Madison,Wisconsin) absorptiometer.

Plasma glucose was measured by the glucose oxidase method with the use of a YSI glucose analyzer (Yellow Springs Instruments, Yellow Springs, Ohio). Plasma insulin was measured by radioimmunoassay (RIA) (LINCO Research Inc[H1].) which is 100% specific for human insulin with less than 0.2% cross-reactivity with human proinsulin and no cross reactivity with C-peptide or insulin-like growth factor. The intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation are 2.9 to 9.4% and 5.5 to 8.5%, respectively. C-peptide levels were measured by double antibody RIA (DPC, CA) which is 100% specific for C-peptide. The intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation are 1.7 to 8.5% and 2.2 to 8.5% respectively.

First phase insulin (1st PI) and C-peptide (1st PC) were calculated as the mean of 5 determinations from 2.5 to 12.5 minutes of the hyper-C. Second phase insulin (2nd PI) and C-peptide (2nd PC) were calculated as the mean of 8 determinations from 15 to 120 minutes of the hyper-C, as before (6,7).

The distribution of the different variables was examined and the appropriate statistical test applied. Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney test was used for 2 group comparisons. Pearson or Spearman’s correlations were used to examine bivariate relationships. Area under the curve (AUC) was calculated using the trapezoidal rule. P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Results are reported as mean ± SD.

RESULTS

Subjects had normal fasting glucose (82.2 ± 5.4 mg/dl). Fasting insulin ranged from 4.7 – 39.0 µu/ml (mean ± SD: 15.0 ± 7.1 µu/ml) and fasting C-peptide from 0.5 – 2.4 ng/ml (1.4 ± 0.5 ng/ml). Glucose peaked at 30 minutes of the OGTT and Boost test. Similarly, insulin and C-peptide levels peaked at 30 minutes of the OGTT and Boost.

During the hyperglycemic clamp, 1st phase insulin levels were 114.1±106.6 µu/ml and C-peptide levels were 5.0±2.5 ng/ml.

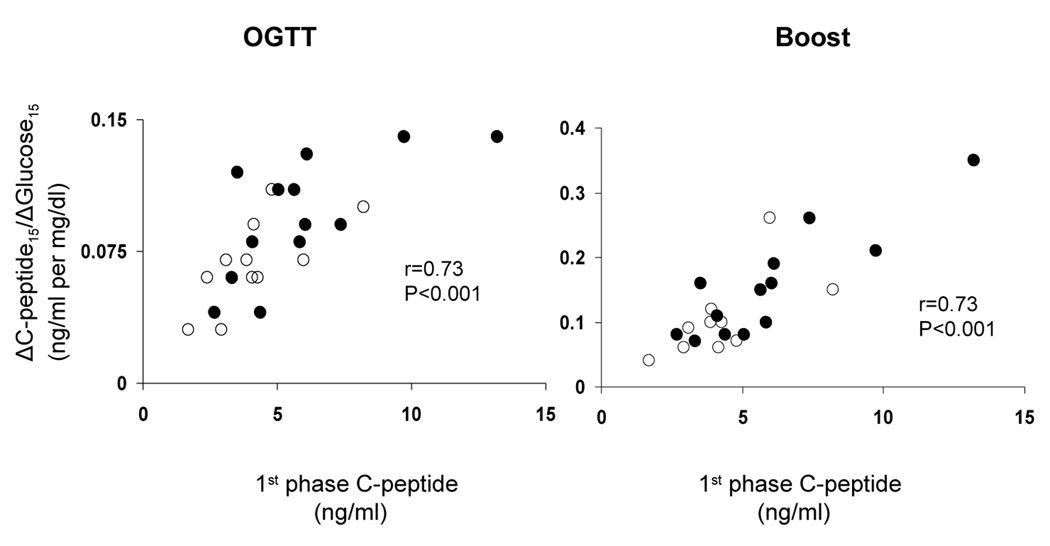

The ratio of the incremental response of insulin and C-peptide to glucose at 15 and 30 minutes of the OGTT (ΔI15/ΔG15, ΔI30/ΔG30, ΔC15/ΔG15, ΔC30/ΔG30) correlated with first-phase insulin and first-phase C-peptide from the hyperglycemic clamp (Table and Figure). However, the best correlate of first phase β-cell function measured during the hyperglycemic clamp was the early 15 min and not the 30 minute values from the oral tests, ΔC15/ΔG15 (r = 0.73, p < 0.001) from the OGTT and ΔC15/ΔG15 (r = 0.73, p < 0.001) from the Boost (Table and Figure). Similarly, the best correlate of second phase β-cell function from the hyperglycemic clamp was ΔC15/ΔG15 (r = 0.71, p < 0.001) from the OGTT and ΔC15/ΔG15 (r = 0.76, p < 0.001) from the Boost.

Table 1.

Correlation of OGTT and Boost derived parameters of insulin secretion to 1st phase insulin (1st PI) and C-peptide (1st PC) during the Hyper-C (r and p values in parenthesis).

| OGTT | ΔI15/ ΔG15 (µu/ml per mg/dl) | ΔC15/ ΔG15 (ng/ml per mg/dl) | ΔI30/ ΔG30 (µu/ml per mg/dl) | ΔC30/ ΔG30 (ng/ml per mg/dl) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyper-C | ||||

| 1st PI (µu/ml) | 0.49 (0.012) | 0.57 (0.003) | 0.56 (0.004) | 0.40 (0.05) |

| 1st PC (ng/ml) | 0.43 (0.03) | 0.73 (<0.001) | 0.37 (0.07) | 0.61 (<0.001) |

| BOOST | ΔI15/ ΔG15 (µu/ml per mg/dl) | ΔC15/ ΔG15 (ng/ml per mg/dl) | ΔI30/ ΔG30 (µu/ml per mg/dl) | ΔC30/ ΔG30 (ng/ml per mg/dl) |

| Hyper-C | ||||

| 1st PI (µu/ml) | 0.67 (0.001) | 0.39 (0.059) | 0.24 (ns) | 0.21 (ns) |

| 1st PC (ng/ml) | 0.57 (0.004) | 0.73 (<0.001) | 0.23 (ns) | 0.45 (0.02) |

Figure.

Relationship of ΔC-peptide15/ΔGlucose15 derived from the OGTT (Left panel) and Boost test (Right panel) to 1st phase C-peptide from the hyperglycemic clamp in normal weight (NW; open circles) and overweight children (OW; filled circles).

Insulin AUC during the OGTT correlated more with 2nd phase (r=0.59, p=0.002) than with 1st phase (r=0.45, p=0.023) insulin secretion from the hyperglycemic clamp. Similarly, C-peptide AUC correlated more with 2nd phase (r=0.61, p=0.001) than 1st phase (r=0.50, p=0.011) C-peptide levels. Insulin and C-peptide AUC from the boost similarly correlated more with 2nd phase insulin (r=0.43, p=0.03) and C-peptide (r=0.73, p<0.001), respectively.

DISCUSSION

The aim of the current study was to evaluate the utility of a clinical test, the oral glucose tolerance and/or the boost test in providing indices of insulin secretion in normoglycemic children. Our findings demonstrate that 1) the OGTT and Boost tests can be used in children to derive estimates of insulin secretion which correlate well with hyperglycemic clamp-derived measures of β-cell function; 2) the 15 minute and not the 30 minute indices correlate better with the hyperglycemic clamp insulin and C-peptide secretion; 3) C-peptide levels appear to correlate better than insulin levels with the hyperglycemic clamp-derived measures.

The hyperglycemic clamp method (8) is considered the most valid method to measure insulin secretion. However, for epidemiologic studies, and for the follow-up of individual changes in insulin secretion, measurements derived from simpler methods such as the OGTT and mixed meal (e.g. Boost) test are desirable. Although fasting indices are used frequently as surrogate estimates of insulin sensitivity (9–14), they have not been consistently as useful in estimating insulin secretion (13,15–16). Several insulin secretion indices derived from the OGTT have been proposed. The insulinogenic index, calculated as the ratio of the 30 minute increment in insulin to glucose concentration (17), is widely used to estimate insulin secretion (15,18–19) and to predict risk of diabetes (16,20) in both adults and youth. In adolescents, ΔI30/ΔG30 was used to assess insulin secretion in subjects with type 2 diabetes compared with those with impaired glucose tolerance (21) and in normoglycemic obese children (22). In the current study, the 30 minute insulinogenic index correlates only modestly with 1st phase insulin secretion derived from the hyperglycemic clamp (r= 0.56). This is similar to findings in adults in whom the correlation between clamp derived 1st phase insulin and ΔI30/ΔG30 was r=0.2 (23). Also, Philips et al (17) reported r= 0.55 for the relationship between the insulinogenic index and 3 min insulin level as a measure of first phase insulin during intravenous glucose tolerance test in normoglycemic subjects.

Given that the typical sampling times during an OGTT, whether as a clinical or research tool, do not include a 15 minute blood sample (21,22, 24–27), our findings would suggest that a determination of 15 minute insulin and C-peptide levels may be a better reflection of early phase insulin secretion than the 30 minute. Moreover, because the impairment in first phase insulin secretion is the earliest abnormality in the transition from a normoglycemic state to impaired glucose tolerance/pre diabetes to type 2 diabetes in adults (1,28) and youth (29–31), a 15 minute determination may give a more reliable estimate of changes in first phase insulin secretion in observational or intervention studies.

It was also interesting to note that the 15 minute insulinogenic index overall correlated better with the 1st phase insulin and C-peptide levels despite the peak levels of insulin and C-peptide being at 30 minutes of the OGTT and Boost. The 30 minute peak levels could be attributed to an incretin effect not observed after the IV glucose challenge during the clamp. Post OGTT incretin effect peaks at around 20–40 minutes in normoglycemic and impaired glucose tolerant subjects (32). We did not measure incretin hormone levels in the current study. Given that incretin effect is preserved longer than insulin secretion in adults with impaired glucose tolerance (32), assessing the 15 minute insulinogenic index may be more valuable in detecting early impairments in β-cell function preceding impairment in incretins.

Another observation in the present study is that the correlations between C-peptide from the OGTT, Boost, and the hyperglycemic clamp were stronger than that for insulin. This could be related to differences in C-peptide kinetics and insulin clearance (33,34). Insulin clearance is decreased in obesity resulting in higher circulating levels (35). Furthermore, insulin clearance is lower in African American and Hispanic children compared with whites (36–39). These factors do not affect C-peptide levels. Therefore, measuring C-peptide rather than insulin may override problems of race or obesity related differences in insulin clearance and its consequence on circulating insulin levels.

Measurement of C-peptide rather than insulin and early, 15 minutes, rather than 30 minutes may prove more informative in assessing first phase insulin secretion. Additional studies are needed in youth with varying degrees of glucose tolerance to determine if the current observations, in normally glucose tolerant children, hold true for those with glucose intolerance and abnormalities in first phase insulin secretion.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the nurses of the Pediatric Clinical & Translational Research Center, previously General Clinical Research Center, for their expert nursing assistance, Resa Stauffer for her laboratory expertise and Pat Antonio for secretarial assistance. These studies would not have been possible without the recruitment efforts of Sandy Stange and most importantly the commitment of the volunteer children and their parents.

This work has been supported by Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh Scientific Program (FB), The Pediatric Clinical and translational Research Center at Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh MO1-RR00084 and UL1 RR024153, K24HD01357 (SA), The Endocrine Fellows Foundation (FB), Genentech Center for Clinical Research and Education (FB), Pharmacia Endocrine Care International Fund for Research and Education (FB)/ Pfizer Endocrine Care Team.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kahn SE. The importance of β-cell failure in the development and progression of type 2 diabetes. JCEM. 2001;86:4047–4058. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.9.7713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strauss RS, Pollack HA. Epidemic increase in childhood overweight, 1986–1998. JAMA. 2001;286:2845–2848. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.22.2845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogden C, Flegal K, Carroll M, Johnson C. Prevalence and trends in Overweight among US children and Adolescents, 1999–2000. JAMA. 2002;288:1728–1732. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gungor N, Hannon T, Libman I, Bacha F, Arslanian S. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in youth: the complete picture to date. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2005;52:1579–1609. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bacha F, Arslanian S. Ghrelin Suppression in Overweight Children: A Manifestation of Insulin Resistance? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:2725–2730. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arslanian S, Suprasongsin C. Differences in the in vivo insulin secretion and sensitivity in healthy black vs white adolescents. J Pediatr. 1996;129:440–444. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arslanian S, Suprasongsin C, Janosky JE. Insulin secretion and sensitivity in black versus white prepubertal healthy children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:1923–1927. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.6.4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeFronzo RA, Tobin JD, Andres R. Glucose clamp technique: A method for quantifying insulin secretion and resistance. Am J Physiol. 1979;237:E214–E223. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1979.237.3.E214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gungor N, Saad R, Janosky J, Arslanian S. Validation of surrogate estimates of insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion in children and adolescents. J Pediatr. 2004;144:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2003.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28:412–419. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katz A, Nambi SS, Mather K, Baron AD, Follmann DA, Sullivan G, et al. Quantitative insulin sensitivity check index: A simple, accurate method for assessing insulin sensitivity in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:2402–2410. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.7.6661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang TT-K, Johnson MS, Goran MI. Development of a prediction equation for insulin sensitivity from anthropometry and fasting insulin in prepubertal and early pubertal children. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1203–1210. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.7.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conwell LS, Trost SG, Brown WJ, Batch JA. Indexes of insulin resistance and secretion in obese children and adolescents. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:314–319. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uwaifo GI, Fallon EM, Chin J, Elbert J, Parikh SJ, Yanovski JA. Indices of insulin action, disposal, and secretion derived from fasting samples and clamps in normal glucose-tolerant black and white children. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:2081–2087. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.11.2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guzzaloni G, Grugni G, Mazzilli G, Moro D, Morabito F. Comparison between β-cell function and insulin resistance indexes in prepubertal and pubertal obese children. Metabolism. 2002;51:1011–1016. doi: 10.1053/meta.2002.34029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanson RL, Pratley RE, Bogardus C, Narayan KMV, Roumain JML, Imperatore G, et al. Evaluation of simple indices of insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion for use in epidemiologic studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:190–198. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phillips DIW, Clark PM, Hales CN, Osmond C. Understanding oral glucose tolerance: Comparison of glucose or insulin measurements during the oral glucose tolerance test with specific measurements of insulin resistance and insulin secretion. Diabetic Medicine. 1994;11:286–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1994.tb00273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cederholm J, Wibell L. Insulin release and peripheral sensitivity at the oral glucose tolerance test. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 1990;10:167–175. doi: 10.1016/0168-8227(90)90040-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jensen CC, Cnop M, Hull RL, Fujimoto WY, Kahn SE American Diabetes Association GENNID Study Group. β-cell function is a major contributor to oral glucose tolerance in high-risk relatives of four ethnic groups in the U.S. Diabetes. 2002;51:2170–2178. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.7.2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haffner SM, Miettinen H, Gaskill SP, Stern MP. Decreased insulin secretion and increased insulin resistance are independently related to the 7-year risk of NIDDM in Mexican-Americans. Diabetes. 1995;44:1386–1391. doi: 10.2337/diab.44.12.1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sinha R, Fisch G, Teague B, Tamborlane W, Banyas B, Allen K, et al. Prevalence of Impaired Glucose Tolerance among Children and Adolescents with Marked Obesity. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:802–810. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yeckel CW, Taksali SE, Dziura J, Weiss R, Burgert TS, Sherwin RS, et al. The normal glucose tolerance continuum in obese youth: evidence for impairment in beta-cell function independent of insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:747–754. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stumvoll M, Mitrakou A, Pimenta W, Jenssen T, Yki-Jarvinen H, Van Haeften T, et al. Use of the oral glucose tolerance test to assess insulin release and insulin sensitivity. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:295–301. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.3.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Invitti C, Guzzaloni G, Gilardini L, Morabito F, Viberti G. Prevalence and concomitants of glucose intolerance in European obese children and adolescents. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:118–124. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yeckel CW, Weiss R, Dziura J, Taksali SE, Dufour S, Burgert TS, et al. Validation of insulin sensitivity indices from oral glucose tolerance test parameters in obese children and adolescents. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:1096–1101. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wiegand S, Mai kowski U, Blankenstein O, Biebermann H, Tarnow P, Gruters A. Type 2 diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in European children and adolescents with obesity – a problem that is no longer restricted to minority groups. European J of Endocrinology. 2004;151:199–206. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1510199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buchanan TA, Xiang AH, Peters RK, Kjos SL, Marroquin A, Goico J, et al. Preservation of pancreatic (beta)-cell function and prevention of type 2 diabetes by pharmacological treatment of insulin resistance in high-risk Hispanic women. Diabetes. 2002;51:2796–2803. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.9.2796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Polonsky KS, Sturis J, Bell GI. Non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus – a genetically programmed failure of the beta-cell to compensate for insulin resistance. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:777–783. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603213341207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bacha F, Gungor N, Arslanian S. Pre-Diabetes in obese youth: a defect in insulin sensitivity (IS) or insulin secretion (ISC)? Diabetes. 55(S1):A68. 292-OR. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arslanian SA, Lewy VD, Danadian K. Glucose intolerance in obese adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome: roles of insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction and risk of cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:66–71. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.1.7123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiss R, Caprio S, Trombetta M, Taksali SE, Tamborlane WV, Bonadonna R. β-cell function across the spectrum of glucose tolerance in obese youth. Diabetes. 2005;54:1735–1743. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.6.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muscelli E, Mari A, Natali A, Astiarraga BD, Camastra S, Frascerra S, et al. Impact of incretion hormones on β-cell function in subjects with normal or impaired glucose tolerance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;291:E1144–E1150. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00571.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Polonsky KS, Licinio-Paixao J, Given BD, Pugh W, Rue P, Galloway J, et al. Use of biosynthetic human C-peptide in the measurement of insulin secretion rates in normal volunteers and type 1 diabetic patients. J Clin Invest. 1986;77:98–105. doi: 10.1172/JCI112308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Faber OK, Hagen C, Binder C, Markussen J, Naithani VK, Blix PM, et al. Kinetics of human connecting peptide in normal and diabetic subjects. J Clin Invest. 1978;62:197–203. doi: 10.1172/JCI109106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang X, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. Relation of obesity to insulin secretion and clearance in adolescents: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Int J Obes relat Metab Disord. 1996;20:951–956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arslanian SA, Saad R, Lewy V, Danadian K, Janosky J. Hyperinsulinemia in Africa-American children: decreased insulin clearance and increased insulin secretion and its relationship to insulin sensitivity. Diabetes. 2002;51:3014–3019. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.10.3014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goran MI, Bergman RN, Cruz ML, Watanabe R. Insulin resistance and associated compensatory responses in African-American and Hispanic children. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:2184–2190. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.12.2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gower BA, Granger WM, Franklin F, Shewchuk RM, Goran MI. Contribution of insulin secretion and clearance to glucose-induced insulin concentration in African-American and Caucasian children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:2218–2224. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.5.8498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang X, Sathanur S, Radhakrishnamurthy B, Dalferes ER, Jr, Berenson GS. Racial (Black-White) differences in insulin secretion and clearance in adolescents: The Bogalusa Heart Study. Pediatrics. 1996;97:357–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]