Abstract

Cilia perform essential motile and sensory functions central to many developmental and physiological processes. Disruption of their structure or function can have profound phenotypic consequences, and has been linked to left-right patterning and polycystic kidney disease. In a forward genetic screen for mutations affecting ciliary motility, we isolated zebrafish mutant hu255H. The mutation was found to disrupt an ortholog of the uncharacterized highly conserved human SDS22-like leucine-rich repeat (LRR)-containing protein LRRC50 (16q24.1) and Chlamydomonas Oda7p. Zebrafish lrrc50 is specifically expressed in all ciliated tissues. lrrc50hu255H mutants develop pronephric cysts with an increased proliferative index, severely reduced brush border, and disorganized pronephric cilia manifesting impaired localized fluid flow consistent with ciliary dysfunction. Electron microscopy analysis revealed ultrastructural irregularities of the dynein arms and misalignments of the outer-doublet microtubules on the ciliary axonemes, suggesting instability of the ciliary architecture in lrrc50hu255H mutants. The SDS22-like leucine-rich repeats present in Lrrc50 are necessary for proper protein function, since injection of a deletion construct of the first LRR did not rescue the zebrafish mutant phenotype. Subcellular distribution of human LRRC50-EGFP in MDCK and HEK293T cells is diffusely cytoplasmic and concentrated at the mitotic spindle poles and cilium. LRRC50 RNAi knock-down in human proximal tubule HK-2 cells thoroughly recapitulated the zebrafish brush border and cilia phenotype, suggesting conservation of LRRC50 function between both species. In summary, we present the first genetic vertebrate model for lrrc50 function and propose LRRC50 to be a novel candidate gene for human cystic kidney disease, involved in regulation of microtubule-based cilia and actin-based brush border microvilli.

Cilia are highly complex evolutionarily conserved microtubule-based cellular extensions that perform essential motile and sensory functions central to many developmental and physiological processes.1 They are nucleated by the centrosome-derived basal body and comprise a 9 + 2 or 9 + 0 microtubule doublet backbone or axoneme. Ciliary motility depends on the presence of inner (IDAs) and outer dynein arms (ODAs) attached to the peripheral microtubule doublets. These dynein arms are multisubunit protein complexes with ATPase activity that promote sliding between adjacent microtubules, and their coordinated activation and inactivation generates a ciliary wave. Whereas ODAs influence ciliary beat frequency, IDAs are involved in generation of the ciliary waveform.2,3

Immotile or misassembled cilia have been implicated in many pathologies, including left-right patterning defects and polycystic kidney disease (PKD).1,4–6 Many proteins involved in PKD localize to the basal body, centrosome, and/or renal cilia, where they are involved in a wide variety of processes including modulating signaling pathways, cell-cycle control, and planar cell polarity (for reviews see references7–10). Cilia are now perceived as important cellular antennae, and mechanisms underlying ciliogenesis and cilia maintenance have recently become a major focus of research, including systematic bioinformatic screens to define a comprehensive ciliary proteome or ciliome.4,11–16

In search for novel genes essential for ciliary motility, we performed a forward genetic N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) screen in zebrafish. Here, we report the isolation of a mutant with ciliary dyskinesia that develops proliferative kidney cysts. The causative gene encodes the highly conserved leucine-rich repeat (LRR)-containing protein Lrrc50. Recently, Mitchell and co-workers17 identified the Chlamydomonas oda7 locus to encode an lrrc50 ortholog. Oda7p is an axonemal dynein-associated protein, and its loss of function results in the absence of outer row dyneins and a reduced flagellar beat frequency. We report the first functional characterization of lrrc50 in both zebrafish and mammalian cell culture systems. Our data suggest LRRC50 to be a ciliary component in vertebrates. We propose LRRC50 to be a novel candidate gene for human cystic kidney disease, involved in the regulation of apical cell specializations, including motile cilia and actin-based microvilli.

RESULTS

To identify recessive mutations affecting ciliary motility, we performed a forward genetic ENU mutagenesis screen in zebrafish. F3-generation embryos were screened, and mutant hu255H (hereafter called lrrc50hu255H) was isolated, based on the absence of motile cilia in the nose and neural tube (Supplemental Figure 1).

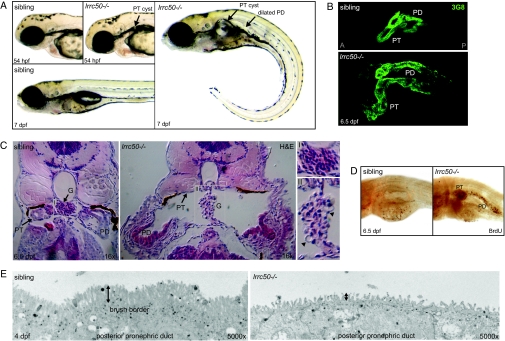

lrrc50hu255H Mutants Develop Kidney Cysts and Brush Border Abnormalities

lrrc50hu255H mutant embryos manifest a pronounced ventral body curvature. Approximately 2.5 d postfertilization (dpf), fluid-filled cysts became apparent in the pronephric tubule region. As development progressed, pronephric tubular cysts expanded and bulged out behind the pectoral fin, and the pronephric duct became dilated (Figure 1, A and B). Histologic sections of the mutant pronephros showed the glomerulus to be stretched at the midline and glomerular cells to be enlarged (Figure 1C, insert). The cuboidal epithelium seen in the wild-type pronephric tubule was completely flattened (Figure 1C). To examine whether the observed pronephric phenotypes correspond to increased localized proliferation, we performed a time-course bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation assay. Before visible cyst development, no obvious difference in proliferation rate was observed between lrrc50hu255H mutants and siblings at 50 h postfertilization (hpf; Supplemental Figure 2A). In 3-d-old mutants, however, we observed increased proliferation in the pronephric tubule (16 of 18 animals) where the first cystic expansion occurs (Supplemental Figure 2, B and C). As development progressed, increased proliferation became more pronounced and was detected in both lrrc50hu255H−/− pronephric tubules and ducts (35 of 35; Figure 1D). These data indicate pronephric proliferation to be closely associated with pronephric cyst development in lrrc50hu255H mutants. Further ultrastructural analyses revealed a severely reduced brush border with shorter microvilli in posterior pronephric ducts of 4 dpf mutants (Figure 1E). Because prominent irregularities of the pronephric duct brush border microvilli were already observed in 2 dpf lrrc50hu255H mutants without visible tubular cysts and in 3 dpf mutants with tubular cysts but without visible dilation of the pronephric duct (Supplemental Figure 3), we suggest this to represent a primary defect. Homozygous mutant embryos ultimately die during early larval stages, at approximately 8 dpf, as a result of severe edema that is likely to be a consequence of pronephric disease progression.

Figure 1.

lrrc50 is involved in the development of cystic kidney disease and brush border abnormalities in zebrafish. (A) lrrc50hu255H mutants are characterized by a curved body axis, the development of pronephric tubular (PT) cysts, and dilated pronephric ducts (PD), as shown at 54 hpf and 7 dpf. (B) Confocal imaging with Cy3-labeled 3G8 (green), staining the lateral part of the PT and the anterior half of the PD in 6.5 dpf embryos. (C) Cross-sections (hematoxylin and eosin) of a wild-type and lrrc50hu255H−/− pronephros at 6.5 dpf. Mutants show a grossly distended cyst in place of the pronephric tubule (black arrow), glomerular defects, and dilated pronephric ducts. An enlargement of the glomerulus of a wild-type fish (detail insert I) and a lrrc50hu255H mutant glomerulus with dilated cells (black arrowheads; detail insert II) are depicted in the right panels. (D) BrdU incorporation demonstrates increased proliferation in the pronephric tubule and pronephric duct in lrrc50hu255H mutants at 6.5 dpf. (E) Ultrastructural analysis reveals a severe reduction of the brush border (vertical arrows) in mutant posterior pronephric duct cells at 4 dpf. A, anterior; P, posterior.

lrrc50hu255H Is Required for Cilia Function in Zebrafish

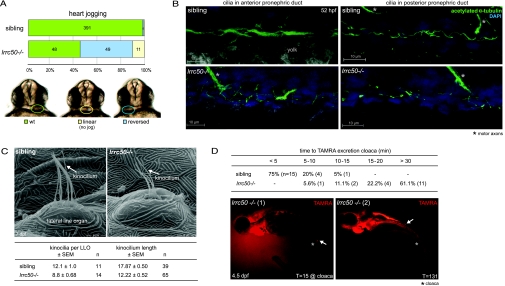

Motile cilia in Kupffer's vesicle (KV) are essential for breaking bilateral symmetry in zebrafish, and in this respect KV is similar to the mouse node.18–21 In lrrc50hu255H mutants, ciliary motility in KV was not observed (data not shown). Although irregularities in ciliary distribution in KV are found (7 of 9), cilia number and length are not strongly affected (Supplemental Figure 4A). To determine whether loss of cilia-dependent fluid flow in KV resulted in laterality defects, we performed in situ hybridization analysis for the first asymmetrically expressed nodal-related gene southpaw (spaw).22,23 We observed randomized expression in lrrc50hu255H−/− at the 18 somite stage (Supplemental Figure 4B). In zebrafish, the first morphologic marker for a break in symmetry is the leftward movement of the heart, called jogging. lrrc50hu255H mutants display a randomized left-right polarity of the heart, as illustrated by altered heart jogging in somewhat more than half of the embryos (Figure 2A). Sibling embryos manifested a very low level of abnormal jogging (7 [1.8%] of 398). Similarly, polarity of the visceral organs (liver, pancreas, and gut) is affected in lrrc50hu255H−/− (Supplemental Figure 4C). In humans and mice, organ left-right polarity disturbances (situs inversus) have been strongly associated with impaired cilia function in early embryogenesis,10,24 which support a profound cilia defect in the lrrc50hu255H mutants.

Figure 2.

lrrc50 is required for cilia function in zebrafish. (A) Dysfunctional cilia in KV are implicated in left-right polarity defects, characterized by random heart jogging in lrrc50 mutants. Absolute numbers of embryos scored are depicted in the bars; the bottom panel displays representative frontal images of the different heart jogging phenotypes. (B) Confocal analysis of cilia in the anterior (left) and posterior pronephric duct (right) immunostained with anti-acetylated α-tubulin (green) and DAPI (blue). Cilia in lrrc50hu255H mutants appear morphologically disorganized at 52 hpf. *Motor axons, which also stain for acetylated tubulin. (C) Scanning electron micrographs of the lateral line organs (LLO) show a reduction in kinocilia number and length in 7 dpf lrrc50hu255H mutants. (D) For investigation of the fluid excretion via the pronephros, 4.5 dpf embryos were administered an injection of TAMRA. Whereas in wild-type siblings the first TAMRA excretion via the cloaca (*) can be observed within 5 min, in mutants, time to excretion is markedly slower (mutant 1) or completely absent (mutant 2). White arrowheads indicate final position TAMRA. Glomerular filtration does not seem to be affected, since TAMRA dye accumulation can be seen in both the pronephric tubule and anterior pronephric duct. T, time after injection.

Cilia in lrrc50hu255H mutants appear morphologically different in organization and distribution, as shown by confocal analysis of cilia in the anterior and posterior pronephric duct of 52 hpf embryos immunostained with α-acetylated α-tubulin (green) and DAPI (blue; Figure 2B). Because of the densely packed cilia in the wild-type pronephros, we were unable to quantify this defect confidently. We examined the lateral line organs and found kinocilium number (with median values of 12.1 versus 8.8 in lrrc50hu255H) and length (median 17.87 versus 12.22 μm in lrrc50hu255H) to be reduced in 7 dpf lrrc50hu255H mutants (Figure 2C).

Ciliary motility in the lrrc50hu255H −/− pronephros was not observed (data not shown). An established functional assay of ciliary motility measures pronephric fluid flow in a dye excretion test.21,25 Tetramethylrhodamine conjugated dextran (TAMRA) was injected into the heart of 4.5 dpf embryos, and excretion of fluorescent dye at the cloaca (end of urinary tract) was monitored. In wild-type animals, TAMRA was filtered by the glomerulus and excreted via the pronephric ducts at the cloaca, generally within 5 min (75%; n = 15) or between 5 and 10 min (20%; n = 4) after injection as a result of the cloaca-directed ciliary beat pattern; however, dye excretion in mutant embryos was markedly slower (33.3% in 10 to 20 min; n = 6) or completely absent (61.1% >30 min; n = 11; Figure 2D, white arrows). Glomerular filtration did not seem to be affected, because TAMRA dye accumulation was observed in both the pronephric tubule and anterior pronephric duct. These data collectively indicate that lrrc50hu255H −/− cilia defects, as observed in the pronephric ducts and lateral line organs, impair normal ciliary function, resulting in ciliary immotility, left-right polarity defects, a severe pronephric fluid flow deficiency, and the development of pronephric cysts.

Positional Cloning and Expression of lrrc50hu255H

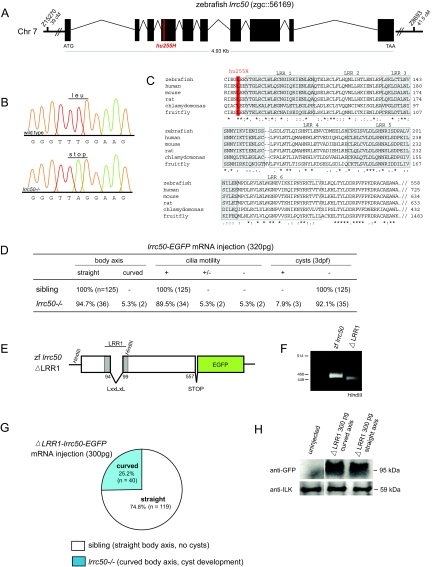

Linkage analysis using 622 meioses positioned the responsible mutation on chromosome 7 between single-sequence length polymorphism markers z15270 (39 cM) and z8693 (41.5 cM), on the Zv4 zebrafish genome assembly. Using this assembly, we analyzed further markers until a region that did not show any recombinations in our mapping panel was identified. Exons from this region were sequenced, and a T/A mutation was identified, changing a conserved leucine into a stop codon (L88X) in a novel Ensembl gene zgc::56169 (Figure 3, A and B). Zgc::56169 encodes an ortholog of the uncharacterized human LRR-containing protein LRRC50 of unknown function. LRRs are short motifs (20 to 30 residues) thought to provide a structural framework for the formation of protein–protein interactions.26,27 The putative LRRs of Lrrc50 are highly conserved from Chlamydomonas (oda7) to Drosophila and vertebrates (Figure 3C), and their orthology is further supported by phylogenetic analysis.17

Figure 3.

Genomic organization and expression pattern of zebrafish lrrc50. (A) Genomic organization of zebrafish lrrc50. lrrc50hu255H was mapped to chromosome 7, flanked by single-sequence length polymorphism markers z15270 (39 cM) and z8693 (41.5 cM) on the MGH mapping panel (http://www.zfin.org). Exons are represented as black boxes. Sequencing revealed a mutation in exon 4 of lrrc50, highlighted in red. (B) In lrrc50hu255H mutants, a T/A mutation is introduced, changing a conserved leucine into a premature stop codon. (C) ClustalW alignment shows Lrrc50 to be a highly conserved protein from Chlamydomonas to human (for accession numbers, see Supplemental Figure 5). LRRs are outlined and lrrc50hu255H L88X is highlighted in red. (D) The mutant phenotype is rescued by injection of 320 pg lrrc50-EGFP mRNA, as scored for body curvature, cilia motility, and pronephric cyst formation after 3 dpf. Absolute numbers of animals scored are in parentheses. (E) Schematic representation of the ΔLRR1-lrrc50-EGFP deletion construct in which the consensus LxxLxL sequence (nucleotides 391 to 408) of the first LRR is removed in frame. (F) HindIII digestion on plasmid DNA shows a reduced band in the deletion construct as compared with full-length lrrc50-EGFP. (G) ΔLRR1-lrrc50-EGFP mRNA is unable to rescue the mutant phenotype; the Mendelian sibling-to-mutant ratio is maintained. (H) Western blot analysis on ΔLRR1-lrrc50-EGFP–injected embryos with α-GFP shows that despite robust expression, the ΔLRR1-lrrc50-EGFP deletion construct cannot rescue the lrrc50hu255H phenotype.

Injection of 320-pg full-length lrrc50-EGFP mRNA into one-cell stage lrrc50hu255H embryos rescued the mutant phenotype: Cilia were motile, the body axis was straight, and pronephric cysts did not develop before 4 dpf (Figure 3D). This experiment confirms the lrrc50 L88X mutation to cause the observed phenotype. To assess whether the conserved LRRs are necessary for proper protein function, we generated a construct deleting the LxxLxL-consensus sequence of the first LRR (Figure 3, E and F). Injection of 300-pg ΔLRR1-lrrc50-EGFP mRNA did not rescue the mutant phenotype (Figure 3G), whereas Western blot analysis for GFP showed proper translation of the injected mRNA in lrrc50hu255h mutants and siblings (Figure 3H).

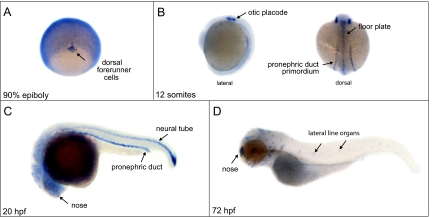

The expression profile of zebrafish lrrc50 was determined by whole-mount in situ hybridization. At gastrula stages, lrrc50 was highly expressed in dorsal forerunner cells (Figure 4A), which aggregate to form the ciliated KV.19 At the 12-somite stage (14 hpf), expression was restricted to the otic placode, pronephric duct primordia, and floorplate (Figure 4B). At 20 hpf, lrrc50 was expressed in the pronephric duct, neural tube, and nose and diffusely in the brain (Figure 4C), and expression became restricted to the nose and lateral line organs at 72 hpf (Figure 4D). Thus, lrrc50 is expressed in ciliated tissues throughout zebrafish development. In lrrc50hu255H mutants lrrc50 mRNA could still be detected (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Zebrafish lrrc50 is expressed in all ciliated tissues. Whole-mount in situ hybridization displays expression at 90% epiboly in the dorsal forerunner cells, which aggregate to form the ciliated KV (A); 12 somites (14 hpf) in the otic placode, pronephric duct primordia, and floor plate (B); 20 hpf in the pronephric duct, neural tube, nose, and diffusely in the brain (C); and 72 hpf in nose and lateral line organs (D).

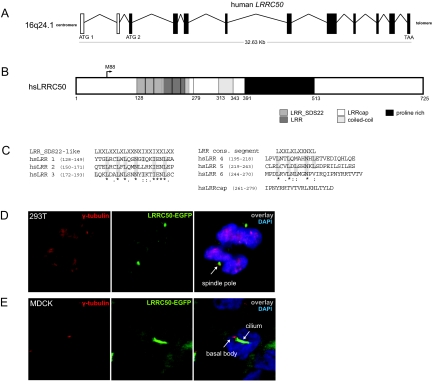

Characterization and Expression of Human LRRC50

Human LRRC50 is an undescribed gene located on chromosome band 16q24.1, and its two predicted transcripts encode proteins of 637 and 725 amino acids (Figure 5A). Both isoforms feature six N-terminal LRR motifs, an LRRcap, a coiled-coil, and a nonconserved proline-rich domain (based on predictions Uniprot/SWISSPROT [Q8NEP3], PROSITE MotifScan,28 and SMART529; Figure 5B). The first three LRRs in LRRC50 showed high homology to the LRR_SDS22-like subfamily (Figure 5C). The sixth LRR (residues 244 to 270) partially overlapped with the putative LRRcap (residues 261 to 279), a motif occurring C-terminally to LRR in “SDS22-like” and “typical” LRR-containing proteins.30,31

Figure 5.

Genomic organization and subcellular localization of human LRRC50. (A) Genomic organization of human LRRC50. A putative alternative translation start site at methionine 88 is in exon 3 (ATG2). (B) Schematic representation of human LRRC50 showing the locations of six putative N-terminal LRRs, an LRRcap partially overlapping with the sixth LRR, a coiled coil, and a nonconserved proline-rich domain. Residue numbers below the bar mark putative domain boundaries. (C) hsLRR 1 to 3 show close homology to the LRR_SDS22-like consensus motif, whereas hsLRR 4 to 6 contain only the conserved consensus LRR sequence. (D) Subcellular localization of LRRC50 was determined by transfection of 293T cells with a full-length LRRC50-EGFP construct. Distribution of LRRC50-EGFP (green) appears diffusely cytoplasmic with bright spots at the spindle poles of mitotic cells as shown by co-staining with γ-tubulin (red). (E) LRRC50-EGFP was observed to localize to the ciliary structure extending from the basal body in MDCK cells but never to the basal body itself as determined by co-staining with α-γ-tubulin. Nuclei are counterstained with DAPI (blue).

To examine normal subcellular localization, we fused the human LRRC50 to EGFP and examined the localization in living and fixed 293T and MDCK kidney cells. Distribution of the LRRC50-EGFP construct was diffusely cytoplasmic, with bright foci at the spindle poles of mitotic cells, as seen by co-localization with spindle pole component γ-tubulin (Figure 5D). In 28 of 44 ciliated MDCK cells scored, LRRC50-EGFP localized to the ciliary structure extending from the basal body immunostained with γ-tubulin (Figure 5E).

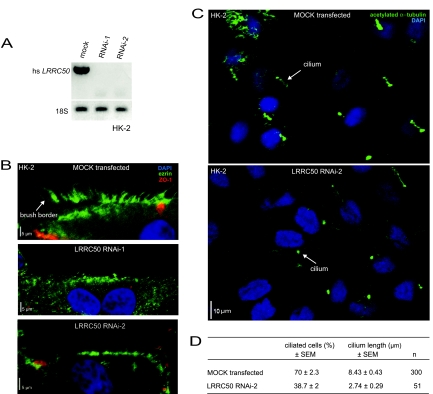

LRRC50 Is Required for Brush Border and Cilia Regulation in Human Kidney Cells

To address the role of LRRC50 in a mammalian cell system, we transfected normal human proximal tubule (HK-2) cells with either of two RNAi constructs (RNAi-1 and RNAi-2). Reverse transcriptase–PCR confirmed both RNAi's to completely knock down levels of the gene product as compared with mock (empty vector)-transfected HK-2 cells (Figure 6A). Interphase cells were immunostained for ezrin, a cytoskeletal protein that anchors actin polymers to the plasma membrane and major component of cellular brush borders.32 Similar to zebrafish lrrc50 mutants, both LRRC50 RNAi constructs severely reduced the brush border at the apical cell surface of polarized HK-2 cells (Figure 6B). Co-staining with zona occulans-1 (ZO-1) did not reveal gross alterations in apical tight junctions.

Figure 6.

LRRC50 is required for brush border and cilia regulation in human proximal tubule cells. (A) Reverse transcriptase–PCR analysis of human LRRC50 in HK-2 cells, either mock (empty vector) transfected or with the indicated RNAi construct, demonstrating complete knockdown of LRRC50 mRNA levels. 18S RNA was taken as loading control. (B) LRRC50 RNAi knockdown with two different constructs in human proximal tubule HK-2 cells reduces the ezrin stained brush border (green). Immunostaining with zona occulans-1 (ZO-1; red) indicates intact tight junctions. (C and D) LRRC50 RNAi-2 knockdown in HK-2 cells reduces the number of ciliated cells and cilia length as shown by anti-acetylated α-tubulin staining (green). Nuclei are counterstained with DAPI (blue).

Reducing LRRC50 levels in HK-2 cells induced a reduction in ciliated interphase cells, from 70% (± 2.3) in mock-transfected to 38.7% (± 2) in RNAi-2–transfected cells, as visualized by α-acetylated α-tubulin immunostaining (Figure 6C). Moreover, in cells that did form a cilium, the ciliary length was reduced from 8.43 (± 0.43) to 2.74 μm (± 0.29) in mock- and RNAi-2–transfected cells, respectively. RNAi-1 produced similar results (data not shown).

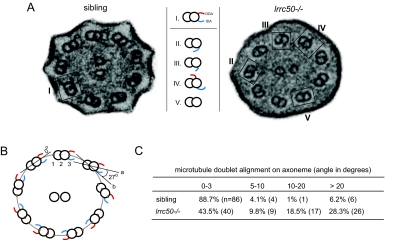

Lrrc50 Ultrastructural Cilia Defects

Because our data suggest a ciliary function for Lrrc50, we performed electron microscopy of pronephric lrrc50hu255H mutant cilia. We observed that these cilia showed ultrastructural irregularities. Most mutant cilia lack the ODA normally present on the outer-doublet microtubules of ciliary axonemes (Figure 7A); however, some axonemes were observed to completely lack all dynein arms or to have misplaced IDA.

Figure 7.

Aberrant ciliary ultrastructure in lrrc50 mutant zebrafish. (A) Electron microscopy reveals ultrastructural irregularities in lrrc50hu255H −/−. Most mutant cilia lack the ODA normally present on the outer-doublet microtubules of ciliary axonemes (I); however, misplacement of the IDA (II/III) or ODA (IV) or complete lack of all dynein arms (V) is also observed. (B) Outer-doublet alignments were measured as depicted in the schematic overview. Briefly, a best-fitting ellipse was drawn through the center (red dot 2) of the doublets. Then, a straight line (a) was drawn through the middle points of the individual doublet microtubules (dots 1 to 3). The angle between the drawn tangent line (b) through dot 2 with the best fitting ellipse and line (a) was measured. (C) lrrc50hu255H mutants show a marked increase in outer-doublet misalignments.

In addition, we observed increased misalignments of outer microtubule doublets in mutant ciliary axonemes. In a wild-type cilium, outer microtubule doublets were aligned in a circle (or ellipse, depending on the cilium angle at sectioning) around the central pair (for schematic representation, see Figure 7B). By determining the tangent angle of the microtubule doublet with respect to the peripheral circle as a whole, we observed that most (88.7%) phenotypically normal siblings displayed outer doublets aligned in a 0 to 3° angle on the axoneme. On the contrary, in lrrc50hu255H mutants, this number was decreased two-fold (43.5%; Figure 7C). We observed outer-doublet misalignments in 56.5% of the measured doublets (n = 52), with angles ranging from 5 up to 75°. Although no obvious correlation between the severity of doublet misalignment and nature of the ultrastructural irregularity could be made, these data suggest instability of the ciliary architecture in lrrc50hu255H mutants.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we present the first functional characterization of zebrafish and human LRRC50, a recently reported ortholog of the axonemal dynein-associated Oda7 protein in Chlamydomonas. LRRC50 was identified as a putative ciliary protein in two independent bioinformatic studies.11,12 Reminiscent of the localization of other PKD-associated proteins (for a comprehensive overview, see reference10), we showed localization of human LRRC50-EGFP at the mitotic spindle poles and cilium in human and dog kidney cells, suggesting LRRC50 to be a ciliary component in vertebrates.

Oda7 mutants lack ODAs normally present on the outer-doublet microtubules of ciliary axonemes and display a reduced flagellar beat frequency.17,33 The zebrafish lrrc50hu255H−/− ciliary phenotype is more severe, including ciliary dyskinesia, ODA defects, and additional dynein arm irregularities and misalignments of outer-microtubule doublets suggestive of architectural instability. Structures on the inner surface of microtubules have been suggested to increase their stability.34 Consistently, Oda7p regulates protozoan-specific dynein heavy-chain α stability and resides in a doublet-associated complex that interacts with both outer row and I1 inner row dyneins,17 possibly in the recently identified outer-inner dynein complex.34 Furthermore, Oda7p is localized to the cytoplasm, where it regulates preassembly of the outer-row dynein complex.33 Cytoplasmic distribution of LRRC50-EGFP might suggest a conserved role for vertebrate LRRC50 in this sense.

Motile cilia in the zebrafish pronephros (9 + 2), KV (9 + 2), neural tube (9 + 0) and teleost lateral line sensory kinocilia (9 + 2) contain dynein arms on their ciliary axonemes21,35; however, it is debated whether immotile mammalian renal monocilia (9 + 0) do. A pioneer study on the ultrastructure of human and rat renal monocilia clearly showed a dynein arm–like structure pointing outward from the microtubule doublets,36 whereas in mouse, no dynein arms were observed.37 The literature remains elusive on this issue, and, as Ibañez-Tallon et al.1 stated, electron microscopy has not yet verified whether dynein arms are actually present in human renal monocilia. Nonetheless, we report conserved LRRC50 function in the regulation of microtubule-based cilia and actin-based brush border microvilli between zebrafish and humans. It is surprising that an axonemal dynein-associated protein might underlie the regulation of both types of apical structures, and we therefore speculate LRRC50 might have additional and/or converged functions in vertebrates. Interestingly, polycystin 2 function was recently found to be regulated by both microtubular organization involving IFT component KIF3A16 and the actin cytoskeleton via anchoring with actin bundling protein α-actinin.38 Furthermore, myosin VIIa was shown to be a common component of cilia and renal microvilli in mice.39 It is intriguing to speculate that interaction with actin might be a common denominator. Flagellar inner-arm dyneins contain an actin subunit,40 and actin is dynamically turned over in static Chlamydomonas flagella; however, its function remains unknown.41

Pronephric fluid flow deficiency is representative of pronephric ciliary dysfunction in zebrafish.21,25 Although most lrrc50hu255H mutants have impaired fluid excretion, in 39.1% of animals tested, this was markedly slower but not absent, suggestive of residual movement. Similarly, pronephric ciliary movement was not detected in the recently described shy mutant25 either, although 1 of 10 of injected mutants displayed fluorescence at the cloaca after 30 min at 3 dpf. Even though lrrc50hu255H−/− glomerular cells are enlarged, glomerular filtration did not seem to be affected, since TAMRA dye accumulation could be seen in both the pronephric tubule and anterior pronephric duct. Glomerular filtration pressure might contribute to the observed residual pronephric fluid flow.

In mice and humans, it is hypothesized that cyst-lining kidney epithelial cells lose their ability to sense mechanical fluid flow, which may result in dedifferention and hyperproliferation of mutant cells.42,43 We showed pronephric hyperproliferation to be closely associated with, yet never preceding, cystic disease progression in lrrc50hu255H−/− zebrafish embryos, indicating this to be a secondary defect.

LRRC50 seems to be the newest addition to an emerging pattern linking proteins containing the subfamily SDS22-like LRRs to flagellar/ciliary function. Other members include the Chlamydomonas dynein light chain 1, involved in protein–protein interactions in motor complexes44,45; the Ciona flagellar radial spoke protein LRR3746; and Chlamydomonas VFL1 protein, which establishes the correct rotational orientation of basal bodies.47 Trypanosomal TbLRTP was shown to suppress basal body replication and flagellar biogenesis and to play a critical role in cell-cycle control.48 The zebrafish TbLRTP homolog seahorse (lrrc6l) develops pronephric cysts.5,49 We provided direct evidence that the SDS22-like LRRs present in Lrrc50 are necessary for proper protein function, because injection of a deletion construct lacking the consensus LxxLxL sequence of the first LRR did not rescue lrrc50hu255h−/− ciliary dyskinesia and pronephric cyst development. Our data suggest LRRC50 to be a novel candidate gene for human disease affecting the kidney. Identifying LRRC50 interaction partners will help to place LRRC50 in the complex context of ciliogenesis, cilia maintenance, planar cell polarity, and cell-cycle control.

CONCISE METHODS

Zebrafish Strains, Screening Methods, and Positional Cloning

Zebrafish were maintained as described previously,50 and experiments were conducted in accordance with the Dutch guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals. ENU mutagenesis was performed on TL males,51 and F3 embryos were morphologically screened for ciliary motility defects in the neural tube and nose on a Zeiss (http://www.zeiss.com/) Axioplan microscope. Positional cloning was performed using single-sequence length polymorphisms from the MGH mapping panel,52 the Ensembl Zv4 zebrafish genome assembly, and single-nucleotide polymorphism markers (http://cascad.niob.knaw.nl). Candidate genes were sequenced. Marker information is available upon request.

In Situ Hybridization and Immunohistochemistry

Whole-mount in situ hybridizations were performed as described previously53 with minor modifications. A partial 1.3-kb antisense digoxygenin-labeled (Roche, http://www.roche-applied-science.com) mRNA probe for lrrc50 was synthesized from EST clone IMAGp998E0413112Q (BQ419779; RZPD, http://www.imagenes-bio.de). lrrc50 and spaw54 transcripts were purified using NucleoSpin RNA clean-up columns (Macherey-Nagel, http://www.mn-net.com/). Immunohistochemistry for acetylated α-tubulin (1:400; Sigma-Aldrich, http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/), Ntl (notail; 1:100),55 and 3G8 (1:40; gift from Dr. E. Jones56) were performed as described previously.21 Embryos were fixed with Dent's (20% DMSO/80% MeOH) or 4% paraformaldehyde (3G8). Secondary antibodies were goat anti-mouse Alexa 488 (1:500; Molecular Probes, http://www.invitrogen.com/) and goat anti-rabbit Cy3 (1:250; Jackson Laboratories, http://www.jacksonimmuno.com) or Alexa 555 (1:500, Molecular Probes). Confocal images were collected using a Leica DMI 4000B microscope.

BrdU Labeling Studies

Two- and 3-d-old embryos were pulsed with 10 mM BrdU (Sigma-Aldrich) and 15% DMSO in embryo medium on ice for 20 min.57 After several short washes, embryos were incubated at 28°C for 20 or 60 min, respectively. Six-day-old embryos were pulsed with 3 mM BrdU in embryo medium for 6 h at 28°C. Embryos were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and BrdU incorporation was detected with primary anti-BrdU antibody (1:100; DAKO, http://www.dako.com/) and secondary anti-mouse IgG–horseradish peroxidase (1:300; DAKO) as described previously.58

Histology

Transversal plastic sections (7 μm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin using standard protocols.

Generation of Full-Length Zebrafish lrrc50-EGFP and ΔLRR1-lrrc50-EGFP Constructs and mRNA

Full-length zebrafish lrrc50 cDNA was amplified from EST clone IRAKp961I11103Q (BC045963; RZPD) and cloned into the pCS2+ vector, C-terminally fused with EGFP (derived from pEGFP-N2; Clontech, http://www.clontech.com/). Primers were 5′-ACTCCTGGATCCTAATATCACTGCGAAATGAAGACAAA-3′ and 5′-GTCAGTGGATCCTGTCCAGTTCCTCAATCAGAACAGT-3′ (Biolegio, http://www.biolegio.com). Sequence was verified. A deletion construct was generated by removing nucleotides 391 to 408 encoding the consensus LxxLxL of the first LRR (ΔLRR1) using the QuickChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, http://www.stratagene.com) according to the manufacturer's instructions, on the lrrc50-EGFP fusion construct described previously. Primers were 5′-GTATAGAGGGTTTGGAAGAATATACTGGCGAGTGTATGGTATTCGAAAGATTGAAAA-3′ and 5′-TTTTCAATCTTTCGAATACCATTACACTCGCCAGTATATTCTTCCAAACCCTCTATAC-3′ (Biolegio). Clones were verified by HindIII digestion and sequencing. After KpnI linearization, lrrc50-EGFP and ΔLRR1-lrrc50-EGFP mRNA were transcribed in vitro using the SP6 mMESSAGE mMACHINE kit (Ambion, http://www.ambion.com/). Respectively, 320 and 300 pg of mRNA was injected into one-cell-stage embryos within 30 min after fertilization. Only GFP-positive embryos were analyzed, and all embryos were genotyped after termination of the experiment. Furthermore, transcription of the mRNA was verified by Western analysis using an anti-GFP antibody (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). In short, anesthetized embryos were frozen in liquid nitrogen and sonicated on ice in 15 μl of RIPA buffer per embryo, supplemented with protease inhibitors (1:1000 apoprotein, leupeptin, and PMSF [Roche]). Laemmli sample buffer was added (1:1), and samples were boiled for 10 min. One embryo equivalent was loaded per lane, and proteins were separated on an 8% SDS polyacrylamide gel as described previously.59 Anti–integrin-linked kinase (ILK) was used as a loading control (1:4000; Sigma).

Generation of Full-Length Human LRRC50-EGFP

Full-length human LRRC50 cDNA was amplified from verified EST clone IRATp970C0324D6 (BC024009; RZPD) using the Advantage-2 PCR enzyme system (Clontech), introducing a 5′ EcoRI and a 3′ SacII restriction site. Primers were 5′-ACTCCTGAATTCACCACCATGCACCCTGAGCCCTC-3′ and 5′-GTCAGTCCGCGGTATGATGCTTTCGGTGCTGGG-3′ (Biolegio). After EcoRI/SacII digestion, the 2.2-kb product was cloned into the pcDNA3 vector (Stratagene), establishing a C-terminal EGFP fusion (derived from pEGFP-N2; Clontech). Sequence was verified.

Fluorescent Dye Injection and Excretion Assay

For dye excretion assays, 1 nl of a 7-mg/ml tetramethylrhodamine-conjungated 70-k molecular weight dextran (TAMRA; Molecular Probes) solution was injected into the heart of 4.5 dpf embryos that were anesthetized with 100 mM MS222 and embedded in 0.5% agarose. Embryos were monitored under a Leica fluorescence stereo microscope, and the time from injection to the first visible excretion at the cloaca was recorded. Only embryos that immediately after injection showed TAMRA throughout the cardiovascular system were included.

Scanning and Transmission Electron Microscopy

Embryos were fixed in Karnovsky fixative (2% paraformaldehyde, 2.5% glutaraldehyde, 0.08 M Na-cacodylate [pH 7.4], 0.25 mM calcium chloride, and 0.5 mM magnesium chloride [pH 7.4]) for at least 24 h at 4°C. Briefly, for scanning electron microscopy, embryos were dehydrated in ethanol and critical point–dried from CO2. Samples were sputter-coated with 5 nm of Au/Pd, and analyses were conducted at 20-kv accelerating voltage with a Hitachi (http://www.hitachi-hitec.com/global/index.html) S-800 field emission scanning electron microscope. For transmission electron microscopy, samples were postfixed in 1% osmiumtetroxide and embedded in Epon 812. Ultrathin sections (60 nm) were contrasted with 3% uranyl magnesium acetate and lead citrate and viewed with a Jeol (http://www.jeol.com/) JEM 1010 or a Philips (Eindhoven, The Netherlands) CM10 transmission electron microscope.

Cell Culture and Transfection

Cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with antibiotics and 6 to 10% FCS. Transfection with LRRC50-EGFP in pCDNA3 was performed by electroporation (270 V, 1.0 mF). Constructs were co-transfected with pBABE-puro (gift of the Nolan Laboratory, http://www.stanford.edu/group/nolan/index.html) in a 5:1 ratio, then selected with puromycin (1 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) 24 h later.

Immunofluorescence Staining

Confluent cells were cultured on coverslips for 4 d in serum-free medium, then fixed either in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and permeabilized in 0.1% Triton/PBS for 10 min or in ice-cold methanol for 2 min. Primary antibodies used were: α-ezrin (1:400; BD-Pharmingen, http://www.bdbiosciences.com), α-acetylated α-tubulin (1:10,000; Sigma-Aldrich), α-γ-tubulin (1:500; Sigma-Aldrich), α-zona occulans-1 (1:1000; Zymed, http://www.invitrogen.com/). Secondary antibody was goat anti-mouse Alexa 488 (1:500; Molecular Probes) and/or goat anti-rabbit Alexa 568 (1:500; Molecular Probes). Confocal analysis was performed on a Zeiss LSM510. For cilia detection, 300 interphase nuclei (as determined by DAPI) were scored for the presence of cilia without knowledge of the sample identity. Experiments were performed on at least two different days, and the data were combined.

RNAi

shRNAi clones v2HS_73906 (RNAi-1, target CCTTCACAGACATCTTTAA), v2HS_73908 (RNAi-2, target CAGAATATGTGCTTTCCGA), or empty vector (“mock,” pSM2c) were isolated as recommended by the manufacturer (Open Biosystems, http://www.openbiosystems.com/). Ten micrograms of plasmid were co-transfected with 2 μg of pBABE-puro into approximately 2 million HK-2 cells by electroporation on two consecutive days before puromycin selection 24 h later. LRRC50 expression in mock- and RNAi-transfected HK-2 cells was detected by reverse transcriptase–PCR, using standard touchdown PCR (25 cycles) with primers 5′-ATGCACCCTGAGCCCTC-3′ and 5′-GCAGAGTTTTTGCAGGGAAC-3′. 18S RNA was taken as loading control: Primers 5′-AGTTGGTGGAGCGATTTGTC-3′ and 5′-TATTGCTCAATCTCGGGTGG-3′.

DISCLOSURES

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Dutch Cancer Association (UU2006-3565). F.V.E. is supported by the MRC Centre for Developmental and Biomedical Genetics, and R.H.G. is supported by a VIDI award (Netherlands Scientific Organization).

We gratefully acknowledge the Hubrecht Screening Team, Jeroen Korving for tissue sectioning, Leon Tertoolen for data acquisition, Chris Hill (Sheffield University) for transmission, and Jürgen Berger (MPI Tübingen) for scanning electron microscopy. We thank Dr. D. Mitchell for sharing reagents and unpublished data.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

Supplemental information for this article is available online at http://www.jasn.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ibanez-Tallon I, Heintz N, Omran H: To beat or not to beat: Roles of cilia in development and disease. Hum Mol Genet 12: R27–R35, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brokaw CJ: Flagellar movement: A sliding filament model. Science 178: 455–462, 1972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dutcher SK: Flagellar assembly in two hundred and fifty easy-to-follow steps. Trends Genet 11: 398–404, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li JB, Gerdes JM, Haycraft CJ, Fan Y, Teslovich TM, May-Simera H, Li H, Blacque OE, Li L, Leitch CC, Lewis RA, Green JS, Parfrey PS, Leroux MR, Davidson WS, Beales PL, Guay-Woodford LM, Yoder BK, Stormo GD, Katsanis N, Dutcher SK: Comparative genomics identifies a flagellar and basal body proteome that includes the BBS5 human disease gene. Cell 117: 541–552, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun Z, Amsterdam A, Pazour GJ, Cole DG, Miller MS, Hopkins N: A genetic screen in zebrafish identifies cilia genes as a principal cause of cystic kidney. Development 131: 4085–4093, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenbaum JL, Witman GB: Intraflagellar transport. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 3: 813–825, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simons M, Walz G: Polycystic kidney disease: Cell division without a c(l)ue? Kidney Int 70: 854–864, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singla V, Reiter JF: The primary cilium as the cell's antenna: Signaling at a sensory organelle. Science 313: 629–633, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris PC, Torres VE: Understanding pathogenic mechanisms in polycystic kidney disease provides clues for therapy. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 15: 456–463, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bisgrove BW, Yost HJ: The roles of cilia in developmental disorders and disease. Development 133: 4131–4143, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stolc V, Samanta MP, Tongprasit W, Marshall WF: Genome-wide transcriptional analysis of flagellar regeneration in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii identifies orthologs of ciliary disease genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 3703–3707, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Avidor-Reiss T, Maer AM, Koundakjian E, Polyanovsky A, Keil T, Subramaniam S, Zuker CS: Decoding cilia function: Defining specialized genes required for compartmentalized cilia biogenesis. Cell 117: 527–539, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blacque OE, Reardon MJ, Li C, McCarthy J, Mahjoub MR, Ansley SJ, Badano JL, Mah AK, Beales PL, Davidson WS, Johnsen RC, Audeh M, Plasterk RH, Baillie DL, Katsanis N, Quarmby LM, Wicks SR, Leroux MR: Loss of C. elegans BBS-7 and BBS-8 protein function results in cilia defects and compromised intraflagellar transport. Genes Dev 18: 1630–1642, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pazour GJ, Agrin N, Leszyk J, Witman GB: Proteomic analysis of a eukaryotic cilium. J Cell Biol 170: 103–113, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith JC, Northey JG, Garg J, Pearlman RE, Siu KW: Robust method for proteome analysis by MS/MS using an entire translated genome: Demonstration on the ciliome of Tetrahymena thermophila. J Proteome Res 4: 909–919, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Q, Montalbetti N, Wu Y, Ramos AJ, Raychowdhury MK, Chen XZ, Cantiello, HF: Polycystin-2 cation channel function is under the control of microtubular structures in primary cilia of renal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 281: 37566–37575, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freshour J, Yokoyama R, Mitchell DR: Chlamydomonas flagellar outer row dynein assembly protein ODA7 interacts with both outer row and I1 inner row dyneins. J Biol Chem 282: 5404–5412, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Essner JJ, Amack JD, Nyholm MK, Harris EB, Yost HJ: Kupffer's vesicle is a ciliated organ of asymmetry in the zebrafish embryo that initiates left-right development of the brain, heart and gut. Development 132: 1247–1260, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Essner JJ, Vogan KJ, Wagner MK, Tabin CJ, Yost HJ, Brueckner M: Conserved function for embryonic nodal cilia. Nature 418: 37–38, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bisgrove BW, Snarr BS, Emrazian A, Yost HJ: Polaris and polycystin-2 in dorsal forerunner cells and Kupffer's vesicle are required for specification of the zebrafish left-right axis. Dev Biol 287: 274–288, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kramer-Zucker AG, Olale F, Haycraft CJ, Yoder BK, Schier AF, Drummond IA: Cilia-driven fluid flow in the zebrafish pronephros, brain and Kupffer'squosquo; apos; ys vesicle is required for normal organogenesis. Development 132: 1907–1921, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bisgrove BW, Morelli SH, Yost HJ: Genetics of human laterality disorders: Insights from vertebrate model systems. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 4: 1–32, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamada H, Meno C, Watanabe D, Saijoh Y: Establishment of vertebrate left-right asymmetry. Nat Rev Genet 3: 103–113, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peeters H, Devriendt K: Human laterality disorders. Eur J Med Genet 49: 349–362, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao C, Malicki J: Genetic defects of pronephric cilia in zebrafish. Mech Dev 124: 605–616, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kobe B, Deisenhofer J: The leucine-rich repeat: A versatile binding motif. Trends Biochem Sci 19: 415–421, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kobe B, Deisenhofer J: Proteins with leucine-rich repeats. Curr Opin Struct Biol 5: 409–416, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sigrist CJ, Cerutti L, Hulo N, Gattiker A, Falquet L, Pagni M, Bairoch A, Bucher P: PROSITE: A documented database using patterns and profiles as motif descriptors. Brief Bioinform 3: 265–274, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Letunic I, Copley RR, Pils B, Pinkert S, Schultz J, Bork P: SMART 5: Domains in the context of genomes and networks. Nucleic Acids Res 34: D257–D260, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kobe B, Kajava AV: The leucine-rich repeat as a protein recognition motif. Curr Opin Struct Biol 11: 725–732, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ceulemans H, De Maeyer M, Stalmans W, Bollen M: A capping domain for LRR protein interaction modules. FEBS Lett 456: 349–351, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bretscher A, Reczek D, Berryman M: Ezrin: A protein requiring conformational activation to link microfilaments to the plasma membrane in the assembly of cell surface structures. J Cell Sci 110: 3011–3018, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fowkes ME, Mitchell DR: The role of preassembled cytoplasmic complexes in assembly of flagellar dynein subunits. Mol Biol Cell 9: 2337–2347, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nicastro D, Schwartz C, Pierson J, Gaudette R, Porter ME, McIntosh JR: The molecular architecture of axonemes revealed by cryoelectron tomography. Science 313: 944–948, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flock A, Duvall AJ 3rd: The ultrastructure of the kinocilium of the sensory cells in the inner ear and lateral line organs. J Cell Biol 25: 1–8, 1965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Webber WA, Lee J: Fine structure of mammalian renal cilia. Anat Rec 182: 339–343, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mokrzan EM, Lewis JS, Mykytyn K: Differences in renal tubule primary cilia length in a mouse model of Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Nephron Exp Nephrol 106: e88–e96, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Q, Montalbetti N, Shen PY, Dai XQ, Cheeseman CI, Karpinski E, Wu G, Cantiello HF, Chen XZ: Alpha-actinin associates with polycystin-2 and regulates its channel activity. Hum Mol Genet 14: 1587–1603, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolfrum U, Liu X, Schmitt A, Udovichenko IP, Williams DS: Myosin VIIa as a common component of cilia and microvilli. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 40: 261–271, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Piperno G, Luck DJ: An actin-like protein is a component of axonemes from Chlamydomonas flagella. J Biol Chem 254: 2187–2190, 1979 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watanabe Y, Hayashi M, Yagi T, Kamiya R: Turnover of actin in Chlamydomonas flagella detected by fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP). Cell Struct Funct 29: 67–72, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nauli SM, Alenghat FJ, Luo Y, Williams E, Vassilev P, Li X, Elia AE, Lu W, Brown EM, Quinn SJ, Ingber DE, Zhou J: Polycystins 1 and 2 mediate mechanosensation in the primary cilium of kidney cells. Nat Genet 33: 129–137, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamaguchi T, Hempson SJ, Reif GA, Hedge AM, Wallace DP: Calcium restores a normal proliferation phenotype in human polycystic kidney disease epithelial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 178–187, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Benashski SE, Patel-King RS, King SM: Light chain 1 from the Chlamydomonas outer dynein arm is a leucine-rich repeat protein associated with the motor domain of the gamma heavy chain. Biochemistry 38: 7253–7264, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu H, Maciejewski MW, Marintchev A, Benashski SE, Mullen GP, King SM: Solution structure of a dynein motor domain associated light chain. Nat Struct Biol 7: 575–579, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Padma P, Satouh Y, Wakabayashi K, Hozumi A, Ushimaru Y, Kamiya R, Inaba K: Identification of a novel leucine-rich repeat protein as a component of flagellar radial spoke in the Ascidian Ciona intestinalis. Mol Biol Cell 14: 774–785, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Silflow CD, LaVoie M, Tam LW, Tousey S, Sanders M, Wu W, Borodovsky M, Lefebvre PA: The Vfl1 protein in Chlamydomonas localizes in a rotationally asymmetric pattern at the distal ends of the basal bodies. J Cell Biol 153: 63–74, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morgan GW, Denny PW, Vaughan S, Goulding D, Jeffries TR, Smith DF, Gull K, Field MC: An evolutionarily conserved coiled-coil protein implicated in polycystic kidney disease is involved in basal body duplication and flagellar biogenesis in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Cell Biol 25: 3774–3783, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Amsterdam A, Nissen RM, Sun Z, Swindell EC, Farrington S, Hopkins N: Identification of 315 genes essential for early zebrafish development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101: 12792–12797, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Westerfield M: The Zebrafish Book: A Guide for the Laboratory Use of Zebrafish (Danio rerio), Eugene, University of Oregon Press, 1995

- 51.van Eeden FJ, Granato M, Odenthal J, Haffter P: Developmental mutant screens in the zebrafish. Methods Cell Biol 60: 21–41, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shimoda N, Knapik EW, Ziniti J, Sim C, Yamada E, Kaplan S, Jackson D, de Sauvage F, Jacob H, Fishman MC: Zebrafish genetic map with 2000 microsatellite markers. Genomics 58: 219–232, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schulte-Merker S: Looking at embryos. In: Zebrafish: A Practical Approach, edited by Nusslein-Volhard C, Dahm R, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2002

- 54.Long S, Ahmad N, Rebagliati M: The zebrafish nodal-related gene southpaw is required for visceral and diencephalic left-right asymmetry. Development 130: 2303–2316, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schulte-Merker S, Ho RK, Herrmann BG, Nusslein-Volhard C: The protein product of the zebrafish homologue of the mouse T gene is expressed in nuclei of the germ ring and the notochord of the early embryo. Development 116: 1021–1032, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vize PD, Jones EA, Pfister R: Development of the Xenopus pronephric system. Dev Biol 171: 531–540, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Appel B, Givan LA, Eisen JS: Delta-Notch signaling and lateral inhibition in zebrafish spinal cord development. BMC Dev Biol 1: 13, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kimmel CB, Miller CT, Kruze G, Ullmann B, BreMiller RA, Larison KD, Snyder HC: The shaping of pharyngeal cartilages during early development of the zebrafish. Dev Biol 203: 245–263, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Giles RH, Lolkema MP, Snijckers CM, Belderbos M, van der Groep P, Mans DA, van Beest M, van Noort M, Goldschmeding R, van Diest PJ, Clevers H, Voest EE: Interplay between VHL/HIF1alpha and Wnt/beta-catenin pathways during colorectal tumorigenesis. Oncogene 25: 3065–3070, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.