Summary

The relationship between events during the bacterial cell cycle has been the subject of frequent debate. While early models proposed a relatively rigid view in which DNA replication was inextricably coupled to attainment of a specific cell mass and cell division was triggered by the completion of chromosome replication, more recent data suggests these models were oversimplified. Instead, an intricate set of intersecting, and at times opposing, forces coordinate DNA replication, cell division, and cell growth with one another, thereby ensuring the precise spatial and temporal control of cell cycle events.

Introduction

A newborn bacterial cell has to complete a long list of tasks prior to division. Not only must it replicate its DNA and segregate sister chromosomes from one another, the cell must also double in size and precisely position its division machinery. It is critical that all these tasks be coordinated with one another, both spatially and temporally, to ensure the production of viable progeny. In contrast to the eukaryotic cell cycle, where checkpoints ensure that the initiation of one step is dependent upon the completion of the prior step [1,2], the bacterial cell cycle (Figure 1) consists of an overlapping set of parallel processes in which individual steps appear to be only loosely linked together [3]. Here we discuss the bacterial cell cycle with emphasis on the mechanisms responsible for coordinating DNA replication, cell division, and cell growth. For clarity we will first review each process starting with DNA replication, and then discuss how it is coordinated with the rest of the cell cycle.

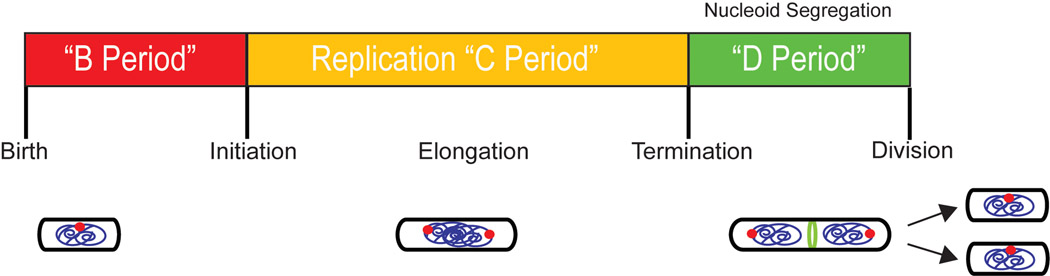

Figure 1. The bacterial cell cycle.

In slow-growing bacteria, the cell cycle is divided into three well-defined periods: i) the B-period – birth to the initiation of DNA replication, ii) the C-period – replication initiation through termination, and iii) the D-period – termination to division. Separation of sister chromosomes occurs concurrently with DNA replication. The origin region is indicated by a red dot. The cytokinetic ring (green) assembles sometime after the initiation of DNA replication, however, division does not occur until nucleoid segregation is complete. The B-period is nonexistent in fast-growing cells in which generation times are less than or equal to the time required for replication and division.

This review focuses on Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis, the best-studied Gram-negative and Gram-positive model systems, respectively. The Gram-negative organism Caulobacter crescentus has also been a fruitful model for studying aspects of the bacterial division cycle, and we will include information from this system where appropriate. However, the C. crescentus cell cycle includes a host of checkpoints that are not present in the other model systems [4]. These checkpoints are likely a consequence of Caulobacter’s requirement for asymmetric division and may not be representative of most bacteria.

The DNA replication cycle

In bacteria, the DNA replication cycle (or C-period) is divided into three stages: initiation, elongation, and termination [5]. Both E. coli and B. subtilis possess an ~4 Mbp circular genome with a single origin of replication (oriC). In both organisms, C-period length is relatively constant under conditions supporting rapid growth rates (~40 minutes in E. coli cells with mass-doubling times under 60 minutes) [6,7].

Replication is initiated by the highly conserved AAA+ ATPase DnaA, which binds adjacent to oriC and induces strand separation [8•]. Melting of the origin region permits the binding of DNA polymerase III (PolIII) and its accessory proteins [9]. During elongation the replication fork proceeds bi-directionally around the chromosome [10], eventually reaching the terminus (terC), where the replication complex disengages from the DNA through the action of specific termination proteins [11].

In both E. coli and B. subtilis, duplicated chromosomes begin to separate from one another prior to the completion of DNA replication [5,12]. The chromosome remains highly organized throughout the entire replication process [13]. In newborn cells the origin is located at midcell where it remains during the initiation of replication. Shortly following duplication, however, the two copies of oriC migrate towards opposite poles of the cell [14]. As replication progresses, the remaining regions of the chromosome separate from one another and follow their respective origins towards opposite poles [15]. The terminus migrates from the pole of a newborn cell to midcell at the end of replication. The duplicated termini flank the invaginating septum during cytokinesis, and are thus positioned at the new cell poles prior to the next round of the cell cycle [16••–18]. Although recent data [19] indicates that the replication complex is more mobile than originally thought [20], it is clear that the DNA passes through the polymerase machinery rather than the entire complex sliding along the DNA [21].

The chromosome exists for the entire cell cycle as a distinct, compact structure that is termed the ‘nucleoid’. Near the end of DNA replication, the nucleoid adopts a bi-lobed, dumb-bell shape that ultimately splits into two independent structures prior to cytokinesis [22]. Efficient nucleoid segregation requires that rod-shaped cells achieve a minimum length, presumably to allow room for separation of these large masses of chromosomal material [23–25••]. To date, the mechanisms driving nucleoid segregation remain uncertain.

Coordinating DNA Replication with Cell Growth

For forty years, dogma has held that the initiation of replication is triggered by achievement of a specific cell size [26] that is independent of growth rate. This idea is based on data on the timing of cell-cycle events in exponentially-growing E. coli and Salmonella typhimurium cells cultured under a variety of conditions [27–29]. Experiments indicating that underexpression and overexpression of DnaA raised or lowered initiation mass, respectively, [30–32] suggest that DnaA levels and/or activity may be responsible for coordinating cell size with the initiation of DNA replication [33,34].

However, the idea that replication is coupled to achievement of a specific cell mass has undergone repeated challenge [16••,25••,35–37]. Flow cytometry data on the DNA content of individual E. coli K-12 cells indicates that initiation mass increases with decreasing growth rates [37]. More recently, a study employing synchronized cultures of E. coli cells also reported that initiation is not coupled to cell mass [16••]. Consistent with these data, B. subtilis mutants that are ~35% shorter than wild type cells appear to exhibit a reduced initiation mass, although the timing of DNA replication and cytokinesis is unperturbed [25••]. Although the E. coli work has been challenged both in terms of approach and interpretation [38,39], together these studies suggest that the factors governing the timing of DNA replication initiation are more complex than originally proposed [26] and are likely to differ between species and potentially even between strains.

Cell Division

The earliest defined event in bacterial cytokinesis is the coordinated assembly of the tubulin-like GTPase FtsZ at the division site [40•]. In vitro, FtsZ assembly into single-stranded polymers or protofilaments is GTP-dependent, and GTP binding and hydrolysis are central to the dynamic nature of FtsZ in vivo [41]. Extending and elaborating on reports that FtsZ forms spirals during sporulation in B. subtilis [42], it has recently been demonstrated that FtsZ exists for much of the cell cycle as a spiral of dynamic polymers that extend the length of the cell. In response to an unidentified cell-cycle signal(s), this spiral coalesces into a ring-like structure (the Z ring) at midcell that serves as a scaffold for assembly of the division machinery [40•,43••,44]. Once formed, the Z ring is present for a large portion of the cell cycle (~20 minutes in B. subtilis cells that are growing with a generation time of 40 minutes [45]). At the end of the cell cycle, the Z ring constricts at the leading edge of the invaginating septum [40•]. The precise temporal and spatial regulation of Z-ring formation is achieved through the concerted action of proteins that modulate FtsZ assembly [40•], and is also sensitive to DNA replication and nucleoid segregation as we discuss below.

Coordinating Cell Division with Cell Growth

Cell division must be coupled with cell growth to ensure that cells divide only when they double in mass to maintain mean cell size in a given a population. This situation requires cells be able to sense achievement of proper cell size and communicate this information to the division apparatus. While it is not known how cells couple division to mass-doubling time, recent data has provided clues about the mechanisms responsible for coordinating division with nutrient availability and cell growth.

Nutrient availability is one of the strongest determinants of cell size in both E. coli and B. subtilis. When grown in rich media where generation times are short, both organisms can be up to twice the size of their slow-growing counterparts cultured in nutrient-poor medium with longer generation times. Nutrient-dependent increases in cell size appear to be primarily a means for these organisms to accommodate the extra DNA generated at fast growth rates [23,24,46]. Both E. coli and B. subtilis are capable of sustaining generation times shorter than the time required to complete chromosome replication [28,47]. This situation requires cells to initiate new rounds of DNA replication prior to completion of the previous round (multifork replication) [27], although only one round of DNA replication is initiated per division cycle. Increasing size with growth rate allows cells to maintain a constant ratio of DNA-to-cell-mass even at faster growth rates [23,24,46].

Work in B. subtilis indicates that this organism has co-opted a conserved metabolic pathway, glucolipid biosynthesis, as a metabolic sensor to detect nutrient status and transmit this information to the division machinery. A key component of this sensor is an effector, UgtP, which interacts directly with FtsZ to inhibit FtsZ assembly. UgtP localization and stability are dependent on glucose availability, thus rendering its activity nutrient-dependent [25••]. While it remains to be seen if a similar mechanism exists in other organisms, a mutation in the E. coli homolog of the first gene in the B. subtilis glucolipid biosynthesis pathway reduces the size of E. coli cells by ~30% [48].

Coordinating Cell Division with DNA Replication and Nucleoid Segregation

DNA replication and nucleoid segregation play significant supporting roles in the regulation of FtsZ assembly and cell division. Although the timing of DNA replication does not influence the timing of division in a direct way [49,50], formation of the division septum typically occurs only after a significant portion of the chromosome has been replicated (~60% in B. subtilis [51]). Data from outgrowing B. subtilis spores suggests that the initiation of DNA replication and replication fork elongation unmask a medial site for FtsZ assembly at midcell by removing oriC and the replication machinery from this position [52,53]. Similar findings have also been reported in C. crescentus [54]. Yet, recent results [19] indicating that the position of the replication machinery is significantly more variable than originally proposed [20], as well as the dearth of information as to how oriC is localized to midcell in the first place [55], make it clear that we are far from a comprehensive understanding of the relationship between replication and division site selection.

In contrast to initiation and elongation, termination does not appear to play a significant role in the timing or position of FtsZ assembly and cytokinesis. Although termination temporally coincides with Z-ring formation [56], blocking replication through terC does not prevent medial Z ring localization [51,57].

The nucleoid itself has also been implicated in the positional regulation of FtsZ assembly and division [58]. The nucleoid occlusion model is based on the long-standing observation that the Z ring and division septum rarely form over unsegregated nucleoids, suggesting that the nucleoid forms a steric barrier to FtsZ assembly. According to this model, nucleoid segregation at the end of the replication cycle produces a medial, nucleoid-free interstice that permits FtsZ assembly and cell division [58]. Genetic data suggests that the division inhibitors MinC and MinD [59], which are concentrated at the cell poles, and the DNA-associated proteins SlmA in E. coli [60] and Noc in B. subtilis [61], function in concert to ensure that FtsZ assembly is restricted to the DNA-free space at midcell. In C. crescentus, the unrelated chromosome-associated protein MipZ serves to coordinate segregation with division [62••].

While it exerts an indirect effect on FtsZ assembly under certain circumstances, the nucleoid’s role in the temporal and spatial control of division is clearly limited. In B. subtilis, for example, FtsZ assembles over an unsegregated nucleoid during sporulation [63], in smc mutants that are defective in chromosome condensation [64,65], in cells in which elongation of the replication fork has been blocked [53], and in cells that exhibit a delay in nucleoid segregation due to reduced size [25••]. It has been suggested that the first two conditions, sporulation and the absence of the chromosome condensation protein SMC, perturb nucleoid structure in such a way that it is no longer able to inhibit division. However, the nucleoid appears to be normal in cells in which replication is blocked [53] and in cells that are defective in cell size control [25••]. These data support a model in which the nucleoid is just one of numerous factors responsible for the regulation of FtsZ assembly and division.

Although DNA replication and nucleoid segregation have a significant influence on cell division, the converse is not true. Blocking the early stages of cell division in both E. coli and B. subtilis leads to the formation of filamentous cells with evenly spaced, fully replicated nucleoids [66]. (Assembly of the division apparatus is necessary, however, for resolution of chromosome dimers in E. coli and C. crescentus through the actions of the bi-functional cell division protein FtsK [67,68].)

It has been suggested by Bates and Klekner [16••] that cell division may influence the timing of DNA replication. Studies of synchronized E. coli cells indicate that replication initiation coincides temporally with the prior division event, suggesting that cell division itself may “license” cells to initiate DNA replication [16••]. This model has been controversial [39], and, in light of the normal nature of DNA replication and nucleoid segregation in filamentous cells (see above), seems to be oversimplified at best. A more likely explanation for the apparent link between the initiation of replication and division is that both events are coordinated with mass doubling time. Coordinating the initiation of DNA replication with mass doubling would ensure that cells initiate DNA replication only once division cycle, giving the appearance that replication is temporally linked to division. The latter model is supported by data from E. coli indicating that initiation mass is influenced by growth rate [37] and is also consistent with results from B. subtilis indicating that cells compensate for a 35% reduction in size by reducing the mass at which they initiate DNA replication without altering the timing of division or DNA replication [26]. In B. subtilis, at least, the apparent constancy of initiation mass appears to be a consequence of growth rate-dependent increases in cell size rather than coupling between the achievement of a specific size and the initiation of DNA replication.

Conclusion

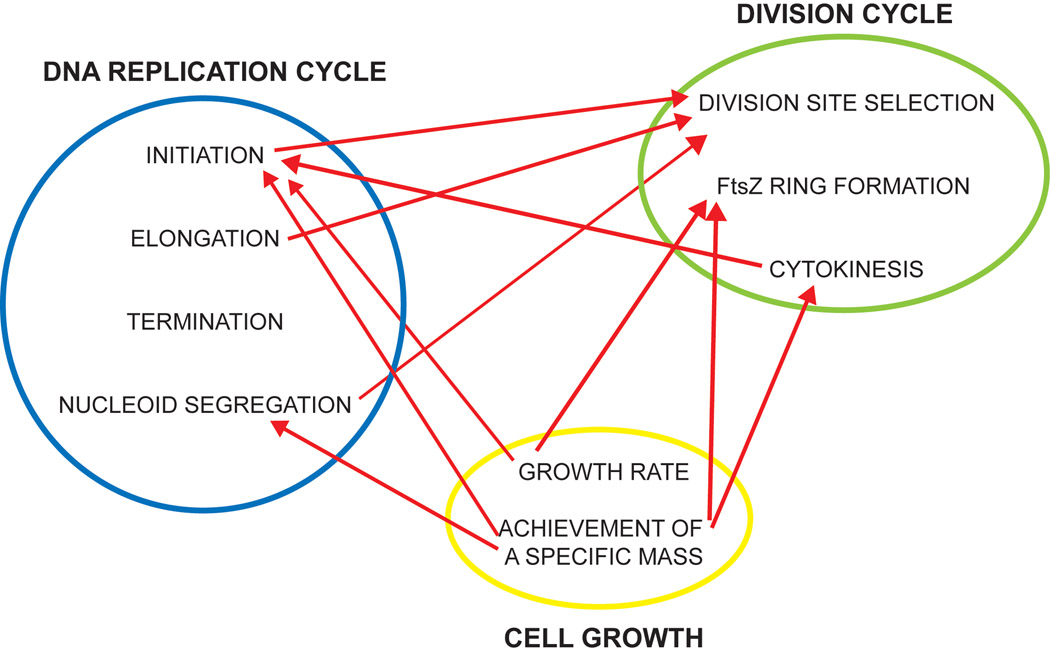

DNA replication, chromosome segregation, cell growth, and cytokinesis are manifestly coordinated in bacterial cells, although not inextricable coupled. Instead of an orderly progression from one step to the next, overlapping events are coordinated through a myriad of interactions, both strong and weak (Figure 2). The reasons for this complexity are not clear. One possibility is that a rapidly changing microbial environment may require an extremely flexible cell cycle. Future research will undoubtedly lead to a refinement of the models discussed in this review and provide insights into outstanding questions, such as the nature of the factors coordinating replication with growth rate, the molecular mechanisms responsible for the spatial control of cell division, and any differences in the regulation employed between varying species.

Figure 2. Multiple points of coordination exist between cell cycle events.

Arrows indicate the direction of influence in coordination. Some interactions have been demonstrated experimentally while others are inferred.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Laura Romberg, Brad Weart, and Bisco Hill for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank the reviewers for their very helpful suggestions and corrections. Work in the Levin lab is supported by a Public Health Services grant (GM64671) from the NIH and a National Science Foundation CAREER award (MCB-0448186) to PAL.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Elledge SJ. Cell cycle checkpoints: Preventing an identity crisis. Science. 1996;274:1664–1672. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith AP, Giménez-Abián JF, Clarke DJ. DNA-damage-independent checkpoints: Yeast and higher eukaryotes. Cell Cycle. 2002;1:16–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nordström K, Bernander R, Dasgupta S. The Escherichia coli cell cycle: One cycle or multiple independent processes that are co-ordinated? Molecular Microbiology. 1991;5:769–774. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goley ED, Iniesta AA, Shapiro L. Cell cycle regulation in Caulobacter: Location, location, location. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:3501–3507. doi: 10.1242/jcs.005967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sherratt DJ. Bacterial chromosome dynamics. Science. 2003;301:780–785. doi: 10.1126/science.1084780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michelsen O, Teixeira de Mattos MJ, Jensen PR, Hansen FG. Precise determinations of C and D periods by flow cytometry in Escherichia coli K-12 and B/r. Microbiology. 2003;149:1001–1010. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharpe ME, Hauser PM, Sharpe RG, Errington J. Bacillus subtilis cell cycle as studied by fluorescence microscopy: Constancy of cell length at initiation of DNA replication and evidence for active nucleoid partitioning. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:547–555. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.3.547-555.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8•.Mott ML, Berger JM. DNA replication initiation: Mechanisms and regulation in bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:343–354. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1640.A recent review of bacterial replication initiation and the regulation of DnaA.

- 9.Johnson A, O'Donnell M. Cellular DNA replicases: Components and dynamics at the replication fork. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:283–315. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pomerantz RT, O'Donnell M. Replisome mechanics: Insights into a twin DNA polymerase machine. Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:156–164. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bussiere DE, Bastia D. Termination of DNA replication of bacterial and plasmid chromosomes. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1611–1618. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nielsen HJ, Li Y, Youngren B, Hansen FG, Austin S. Progressive segregation of the Escherichia coli chromosome. Mol Microbiol. 2006;61:383–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bravo A, Serrano-Heras G, Salas M. Compartmentalization of prokaryotic DNA replication. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2005;29:25–47. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berkmen MB, Grossman AD. Spatial and temporal organization of the Bacillus subtilis replication cycle. Mol Microbiol. 2006;62:57–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lemon KP, Grossman AD. The extrusion-capture model for chromosome partitioning in bacteria. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2031–2041. doi: 10.1101/gad.913301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16••.Bates D, Kleckner N. Chromosome and replisome dynamics in E. coli: Loss of sister cohesion triggers global chromosome movement and mediates chromosome segregation. Cell. 2005;121:899–911. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.013.This paper employs synchronized cells to obtain a high-resolution view of chromosome organization during the E. coli cell cycle. Based on their data, the authors postulate a link between the initiation of DNA replication and the prior cell division event. A controversial, but important paper.

- 17.Lau IF, Filipe SR, Soballe B, Okstad OA, Barre FX, Sherratt DJ. Spatial and temporal organization of replicating Escherichia coli chromosomes. Mol Microbiol. 2003;49:731–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X, Possoz C, Sherratt DJ. Dancing around the divisome: Asymmetric chromosome segregation in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2367–2377. doi: 10.1101/gad.345305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Migocki MD, Lewis PJ, Wake RG, Harry EJ. The midcell replication factory in Bacillus subtilis is highly mobile: Implications for coordinating chromosome replication with other cell cycle events. Mol Microbiol. 2004;54:452–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lemon KP, Grossman AD. Localization of bacterial DNA polymerase: Evidence for a factory model of replication. Science. 1998;282:1516–1519. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5393.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lemon KP, Grossman AD. Movement of replicating DNA through a stationary replisome. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1321–1330. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00130-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woldringh CL, Nanninga N. Structural and physical aspects of bacterial chromosome segregation. J Struct Biol. 2006;156:273–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Donachie WD, Begg K. Cell length, nucleoid separation, and cell division of rod-shaped and spherical cells of Eschericia coli. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:4633–4639. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.9.4633-4639.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharpe ME, Errington J. A fixed distance for separation of newly replicated copies of oriC in Bacillus subtilis: Implications for co-ordination of chromosome segregation and cell division. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:981–990. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25••.Weart RB, Lee AH, Chien AC, Haeusser DP, Hill NS, Levin PA. A metabolic sensor governing cell size in bacteria. Cell. 2007;130:335–347. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.043.In this work, Weart et al. identifiy a metabolic sensor that coordinates cell size with nutrient availability through changes in FtsZ assembly dynamics. This is the first report of a regulator of cell size homeostasis in bacteria.

- 26.Donachie WD. Relationship between cell size and time of initiation of DNA replication. Nature. 1968;219:1077–1079. doi: 10.1038/2191077a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cooper S, Helmstetter CE. Chromosome replication and the division cycle of Escherichia coli B/r. J Mol Biol. 1968;31:519–540. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90425-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Helmstetter CE. DNA synthesis during the division cycle of rapidly growing Escherichia coli B/r. J Mol Biol. 1968;31:507–518. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90424-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schaechter M, Maaloe O, Kjeldgaard NO. Dependency on medium and temperature of cell size and chemical composition during balanced grown of Salmonella typhimurium. J Gen Microbiol. 1958;19:592–606. doi: 10.1099/00221287-19-3-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Atlung T, Hansen FG. Three distinct chromosome replication states are induced by increasing concentrations of DnaA protein in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6537–6545. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.20.6537-6545.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Løbner-Olesen A, Skarstad K, Hansen FG, von Meyenburg K, Boye E. The DnaA protein determines the initiation mass of Escherichia coli K-12. Cell. 1989;57:881–889. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90802-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skarstad K, Løbner-Olesen A, Atlung T, von Meyenburg K, Boye E. Initiation of DNA replication in Escherichia coli after overproduction of the DnaA protein. Mol Gen Genet. 1989;218:50–56. doi: 10.1007/BF00330564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Donachie WD, Blakely GW. Coupling the initiation of chromosome replication to cell size in Escherichia coli. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2003;6:146–150. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(03)00026-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herrick J, Kohiyama M, Atlung T, Hansen FG. The initiation mess? Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:659–666. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.432956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boye E, Nordström K. Coupling the cell cycle to cell growth. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:757–760. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Churchward G, Estiva E, Bremer H. Growth rate-dependent control of chromosome replication initiation in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1981;145:1232–1238. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.3.1232-1238.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wold S, Skarstad K, Steen HB, Stokke T, Boye E. The initiation mass for DNA replication in Escherichia coli K-12 is dependent on growth rate. EMBO J. 1994;13:2097–2102. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06485.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cooper S. Does the initiation mass for DNA replication in Escherichia coli vary with growth rate? Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:1138–1141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cooper S. Regulation of DNA synthesis in bacteria: Analysis of the Bates/Kleckner licensing/initiation-mass model for cell cycle control. Mol Microbiol. 2006;62:303–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40•.Harry E, Monahan L, Thompson L. Bacterial cell division: The mechanism and its precison. Int Rev Cytol. 2006;253:27–94. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(06)53002-5.The most recent, comprehensive review of bacterial cell division.

- 41.Romberg L, Levin PA. Assembly dynamics of the bacterial cell division protein FtsZ: Poised at the edge of stability. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2003;57:125–154. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.012903.074300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ben-Yehuda S, Losick R. Asymmetric cell division in B. subtilis involves a spiral-like intermediate of the cytokinetic protein FtsZ. Cell. 2002;109:257–266. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00698-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43••.Peters PC, Migocki MD, Thoni C, Harry EJ. A new assembly pathway for the cytokinetic Z ring from a dynamic helical structure in vegetatively growing cells of Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 2007;64:487–499. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05673.x.This paper presents compelling data indicating that the medial FtsZ ring is derived from a spiral intermediate that extends the length of the cell, a localization first noticed in sporulation [42].

- 44.Thanedar S, Margolin W. FtsZ exhibits rapid movement and oscillation waves in helix-like patterns in Escherichia coli. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1167–1173. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weart RB, Levin PA. Growth rate-dependent regulation of medial FtsZ ring formation. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:2826–2834. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.9.2826-2834.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sargent MG. Control of cell length in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1975;123:7–19. doi: 10.1128/jb.123.1.7-19.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoshikawa H, O'Sullivan A, Sueoka N. Sequential replication of the Bacillus subtilis chromosome: Regulation of initiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1964;52:973–980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.52.4.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu M, Kleckner N. Molecular cloning and characterization of the pgm gene encoding phosphoglucomutase of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5847–5851. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.18.5847-5851.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bernander R, Nordström K. Chromosome replication does not trigger cell division in E. coli. Cell. 1990;60:365–374. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90588-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gullbrand B, Nordström K. FtsZ ring formation without subsequent cell division after replication runout in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36:1349–1359. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu LJ, Franks AH, Wake RG. Replication through the terminus region of the Bacillus subtilis chromosome is not essential for the formation of a division septum that partitions the DNA. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5711–5715. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.19.5711-5715.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Harry EJ, Rodwell J, Wake RG. Co-ordinating DNA replication with cell division in bacteria: A link between the early stages of a round of replication and mid-cell Z ring assembly. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:33–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Regamey A, Harry EJ, Wake RG. Mid-cell Z ring assembly in the absence of entry into the elongation phase of the round of replication in bacteria: Co-ordinating chromosome replication with cell division. Mol Microbiol. 2000;38:423–434. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Quardokus EM, Brun YV. DNA replication initiation is required for mid-cell positioning of FtsZ rings in Caulobacter crescentus. Mol Microbiol. 2002;45:605–616. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Berkmen MB, Grossman AD. Subcellular positioning of the origin region of the Bacillus subtilis chromosome is independent of sequences within oriC, the site of replication initiation, and the replication initiator DnaA. Mol Microbiol. 2007;63:150–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Den Blaauwen T, Buddelmeijer N, Aarsman ME, Hameete CM, Nanninga N. Timing of FtsZ assembly in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5167–5175. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.17.5167-5175.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McGinness T, Wake RG. Division septation in the absence of chromosome termination in Bacillus subtilis. J Mol Biol. 1979;134:251–264. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(79)90035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rothfield L, Taghbalout A, Shih YL. Spatial control of bacterial division-site placement. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:959–968. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yu XC, Margolin W. FtsZ ring clusters in min and partition mutants: Role of both the Min system and the nucleoid in regulating FtsZ ring localization. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:315–326. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bernhardt TG, de Boer PA. SlmA, a nucleoid-associated, FtsZ binding protein required for blocking septal ring assembly over chromosomes in E. coli. Mol Cell. 2005;18:555–564. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wu LJ, Errington J. Coordination of cell division and chromosome segregation by a nucleoid occlusion protein in Bacillus subtilis. Cell. 2004;117:915–925. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62••.Thanbichler M, Shapiro L. MipZ, a spatial regulator coordinating chromosome segregation with cell division in Caulobacter. Cell. 2006;126:147–162. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.038.In this work, Thanbichler and Shapiro identify a DNA-associated inhibitor of FtsZ assembly that blocks division in Caulobacter until nucleoid segregation is complete.

- 63.Errington J, Bath J, Wu LJ. DNA transport in bacteria. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:538–545. doi: 10.1038/35080005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Britton RA, Lin DC-H, Grossman AD. Characterization of a prokaryotic SMC protein involved in chromosome partitioning. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:1254–1259. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.9.1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Soppa J, Kobayashi K, Noirot-Gros MF, Oesterhelt D, Ehrlich SD, Dervyn E, Ogasawara N, Moriya S. Discovery of two novel families of proteins that are proposed to interact with prokaryotic SMC proteins, and characterization of the Bacillus subtilis family members ScpA and ScpB. Mol Microbiol. 2002;45:59–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dai K, Lutkenhaus J. ftsZ is an essential cell division gene in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3500–3506. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.11.3500-3506.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu G, Draper GC, Donachie WD. FtsK is a bifunctional protein involved in cell division and chromosome localization in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 1998;29:893–903. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang SC, West L, Shapiro L. The bifunctional FtsK protein mediates chromosome partitioning and cell division in Caulobacter. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:1497–1508. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.4.1497-1508.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]