Abstract

Therapies aimed at depleting or blocking the migration of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN or neutrophils) are partially successful in the treatment of neuroinflammatory conditions and in attenuating pain following peripheral nerve injury or subcutaneous inflammation. However, the functional effects of PMN on peripheral sensory neurons such as dorsal root ganglia (DRG) neurons are largely unknown. We hypothesized that PMN are detrimental to neuronal viability in culture and increase neuronal activity and excitability. We demonstrate that isolated peripheral PMN are initially in a relatively resting state but undergo internal oxidative burst and activation by an unknown mechanism within 10 min of co-culture with dissociated DRG cells. Co-culture for 24 hr decreases neuronal count at a threshold <0.4:1 PMN:DRG cell ratio and increases the number of injured and apoptotic neurons. Within 3 min of PMN addition, fluorometric calcium imaging reveals intracellular calcium transients in small size (<25 µm diam) and large size (>25 µm diam) neurons, as well as in capsaicin-sensitive neurons. Furthermore, small size isolectin B4-labeled neurons undergo hyperexcitability manifested as decreased current threshold and increased firing frequency. Although co-culture of PMN and DRG cells does not perfectly model neuro-inflammatory conditions in vivo, these findings suggest that activated PMN can potentially aggravate neuronal injury and cause functional changes to peripheral sensory neurons. Distinguishing the beneficial from the detrimental effects of PMN on neurons may aid in the development of more effective drug therapies for neurological disorders involving neuroinflammation, including painful neuropathies.

Keywords: Neutrophil, Neuron, Sensory, Neuroinflammation, Excitability

Introduction

Neuronal damage is generally associated with recruitment of immune cells to the site of injury, thus resulting in neuroinflammation. During the acute phase of neuroinflammation, circulating polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN or neutrophils) are among the first leukocytes to detect inflammatory signals that trigger PMN rolling along blood vessels, firm adhesion and transendothelial migration into endoneurial space (Nathan 2006). Subsequently, activated PMN release several mediators of cellular toxicity to kill invading pathogens. As such, activated PMN come into close proximity with neurons in a plethora of neurological conditions, including neurodegenerative (multiple sclerosis, Parkinson, Alzheimer) and neurotraumatic disorders (spinal cord injury, ischemia, painful neuropathy). Although the inflammatory response is a critical component of healing and repair, abundant evidence in rodent models suggest that limiting PMN migration can positively influence the outcome of neuronal injury (Ryu et al. 2007, Yamasaki et al. 1997, Prestigiacomo et al. 1999, Connolly et al. 1996, Huang et al. 1999, Taoka et al. 1997).

Blocking PMN migration mediated by cytokine-induced chemoattractant-1 can ameliorate the neurological outcome following stroke (Yamasaki et al. 1997). Neutropenia or deficiency in the intercellular adhesion molecule ICAM-1 that mediates PMN migration confers neuronal protection after experimental cerebral ischemia and stroke (Connolly et al. 1996, Huang et al. 1999, Prestigiacomo et al. 1999, see also Dirnagl et al. 1999, Lo et al. 2003). Administration of anti-P-selectin antibody, which disrupts interaction between activated PMN and endothelial cells, attenuates tissue injury and improves motor performance following spinal cord compression (Taoka et al. 1997).

Neuropathic pain is a neurological disorder caused by nerve lesion whereby patients face unsatisfactory treatment options (Dworkin et al. 2003). In different animal models of sciatic neuropathy, PMN accumulate at the site of nerve lesion (Perkins and Tracey 2000), as well as proximally in lumbar dorsal root ganglia (DRG) (Morin et al. 2007). Notably, neuropathic pain is associated with hyperexcitability of lumbar DRG neurons (Amir et al. 2005, Djouhri et al. 2006, Devor 1999). Interestingly, neuropathic pain is attenuated by blocking PMN migration after 5-hydoxytryptamine (5-HT)-induced subcutaneous inflammation (Oliveira et al. 2007) or by PMN depletion preemptive to sciatic transection (Perkins and Tracey 2000), raising the possibility that PMN targeting of peripheral neurons can lead to hyperexcitability of ‘pain-sensing’ DRG neurons (nociceptors).

Recently, Nguyen et al. (2007) reported that a PMN-conditioned medium is sufficient to cause rapid (within 2 hr) and significant loss of dissociated DRG neurons in culture, whereas Dinkel et al. (2004) demonstrated a delayed reduction in the viability of primary hippocampal neurons 3 days after co-culture with PMN in a cell contact dependant manner. However, the functional effects of PMN on neuronal activity and/or excitability remain unexplored. Therefore, this study was undertaken to characterize the activation state of PMN exposed to DRG cells, to determine the range of PMN titers that significantly reduce DRG neuronal count in culture, and to examine the effect of PMN on DRG neuronal excitability.

Our results indicate that co-incubation of PMN with DRG cells triggers activation of PMN which is detrimental to the viability of neurons, induces neuronal calcium transients, and increases the excitability of nociceptors.

Materials and Methods

Neuronal and PMN cells were obtained from adult (200–250 g) male Sprague Dawley rats that were used according to procedures approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Rhode Island Hospital.

Dissociation and culture of DRG cells

Lumbar 5–6 DRG were acutely dissociated as previously described (Saab et al. 2002, 2003). Whole DRG were excised from rats under isoflurane anesthesia (4%) and placed in RPMI 1640 (Gibco) on ice, stripped from axonal extensions using fine scissors under a microscope and transferred to a solution containing 10 ml RPM1 1640, 15 mg Collagenase A (Roche) followed by Collagenase D (Roche) in 120 µl EDTA (50 mM) and papain (30 µg/ml) for 20 min at 37°C. The tissue was further dissociated by gentle triturating with a pipette, pore-filtered (70 µM) and then washed twice with sterile RPMI 1640. The final suspension was spun down at low speed, with the supernatant aspirated and cells re-suspended in DMEM/F12 media supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% L-glutamate and 1% streptomycin/penicillin (Sigma). Cells were then plated on 14 mm glass bottom microwells in 35 mm Petri dishes (MatTek Cultureware), coated with poly-D-lysine, laminin and collagen. Cell cultures were maintained for 24 hr at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Isolation of peripheral PMN

DRG cells and PMN were obtained from different rats. To obtain viable circulating PMN, whole blood was withdrawn from the inferior vena cava of rats under isoflurane anesthesia (4%). Collected blood (4–5 ml) was allowed to cool to room temperature and carefully layered on an equal volume of Polymorphoprep™ and centrifuged (1250 rpm) for 30 min, whereby two leukocyte bands were visible: The top band consisted of mononuclear cells (‘buffy’ layer containing predominantly peripheral blood mononuclear cells or PBMC) whereas the lower band consisted of mostly PMN granulocytes. The lower band containing PMN was gently extracted and washed in 1XPBS. The solution was further purified by hypotonic erythrocyte lysis with sterile water for 20 sec followed by 10XPBS. After lysing, the final solution was re-suspended in 1XPBS. The purity of the isolated PMN fraction was confirmed under a microscope; only fractions containing >85% PMN were used. This isolation technique yields functionally viable non-adherent PMN capable of migration and superoxide burst under activating conditions as previously described (Morin et al. 2007). Prior to co-culture with DRG cells, in separate experiments, PMN were either fixed with 10% buffered formalin (10 min followed by washing 3 times with PBS), or incubated with NG-monomethyl-L-arginine monoacetate salt (MMA, 1 mM for 30 minutes at 37°C, Calbiochem) dissolved in methanol (200 mM). Fixed PMN were therefore ‘inactivated’, whereas treatment with MMA inhibits all three forms of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS).

PMN internal burst

A typical feature of PMN activation is the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Lavigne et al. 2007, Quinn and Gauss 2004, Yang et al. 2005). Fluorochrome chloromethyl-H2DCFDA (CM-DCF, Molecular Probes C6827) was used for a highly sensitive and real-time assessment of ROS production by PMN. CM-DCF is a cell-permeant FITC-conjugated indicator of ROS that is non-fluorescent until oxidation occurs intracellularly. After PMN isolation as described above, CM-DCF (10 µM) was added to 106 cells/ml at 37°C for 5 min, followed by centrifugation (1200 rpm at −5°C for 5 min), aspiration of supernatant and washing of pellet with cold HBSS. Cells were then immediately viewed with an inverted fluorescent microscope (Nikon eclipse TE 2000U) at excitation and emission wavelengths of 485 and 528 nm. Three fields of vision containing approximately 25–30 PMN were randomly chosen from each well and images were acquired serially every 5 seconds for a total of 10 min. Phorbol–myristate–acetate (PMA, 100 ng/ml, Sigma) was added to induce PMN activation.

Neuronal viability

After estimating the number of isolated PMN in suspension, PMN were co-incubated at different ratios relative to DRG cells in culture referred to as effector-to-target or E/T ratios (0.2:1, 0.4:1, 5:1, 10:1) for 24 hr at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. In other experiments, PBMC were similarly added to DRG cells, supernatant from PMN solution after centrifugation, or supernatant from a PMN:DRG culture after co-incubation for either 15 min or 24 hr. Identification of neurons was based on distinguished morphological features. After 24 hr in culture, neuronal cytoplasm was typically clear and delineated by a distinctly spherical extracellular membrane (Fang et al 2006). These morphological criteria were validated using a neuron-specific marker (Neuron-Specific Nuclear Protein, NeuN, Abcam, used according to manufacturer’s instructions). After washing cells in suspension with 2 ml HBSS, total neuronal count was estimated in treated cultures (3–5 wells/condition) and normalized to neuronal count in untreated cultures (control). In some wells, a sodium channel blocker (Lidocaine, 0.01%, concentration effective for preventing neuronal firing but well below that reported to cause neurotoxicity, Johnson et al. 2004) or tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα, 20 ng/ml, activator of PMN) was added to DRG cells concomitantly with PMN.

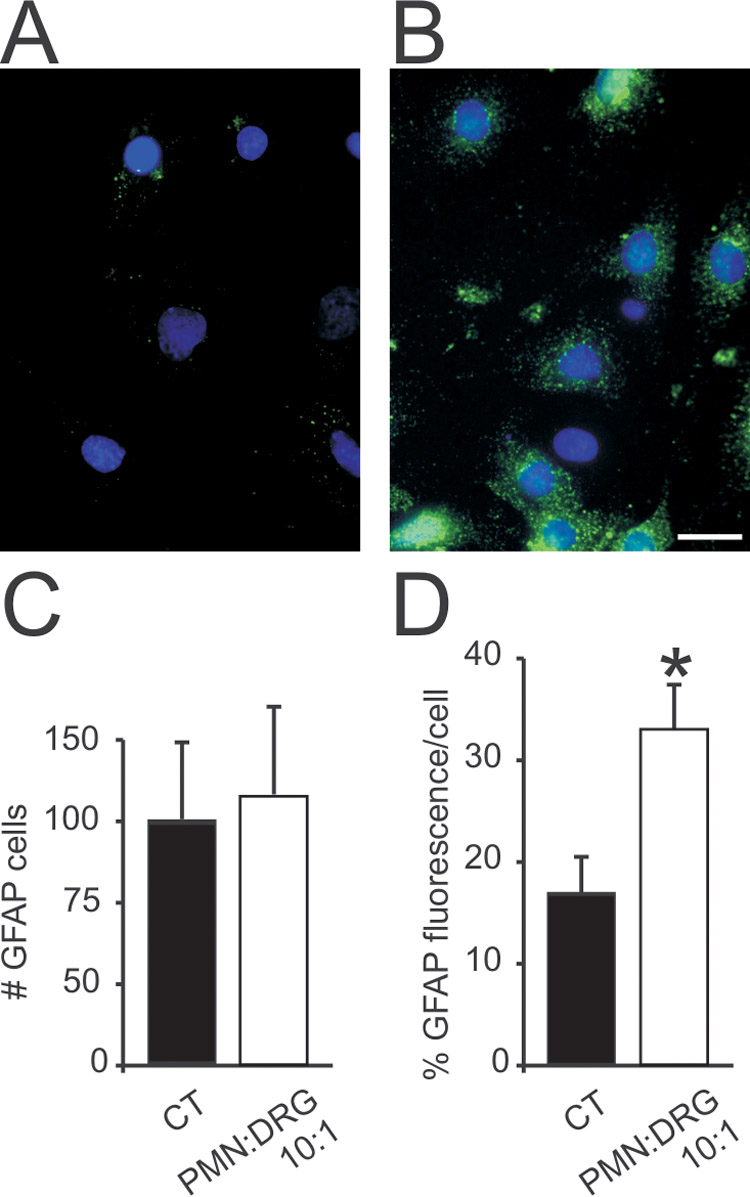

Glial count and activation

To determine glial cell count in DRG cultures, DRG cells with or without PMN were fixed in 10% buffered formalin, washed three times with PBS (5 min each), and blocked for 1 hour with 10% Horse serum in TBST at 37°C. Glial fibrillary acidic protein GFAP primary antibody (mouse anti-GFAP, 1:100 in 10% horse serum for 2 hr at 37°C, Chemicon) was used as a marker of glial intermediate filament (Peters et al. 2007). Cells were then washed three times with PBS (5 min each) before incubation with horse anti-mouse IgG-FITC conjugated secondary antibody (Vector; 1:100 in 10% horse serum for 1 hr at 37°C). To visualize cellular nuclei, PBS was removed from the plate and Fluoroblok-DAPI (Vector) was added. Glial cell count was estimated by using 60X objective images acquired with a FITC filter (GFAP), DAPI filter (nucleus), and brightfield on a Nikon eclipse fluorescent microscope using Nikon elements software bundle. Images were saved for subsequent analysis by an observer blinded to the treatment condition. GFAP-positive cells were counted in each image and the relative mean fluorescence was calculated in each cell after subtracting background fluorescence using ImageJ (www.nih.gov).

Neuronal injury

The fraction of pyknotic neurons (ratio of neurons in culture with a pyknotic profile relative to total neurons) was quantified as a measure of neuronal injury. Neurons with signs of injury manifesting a granular chromatin-dense cytoplasm and discontinuous cell membrane with oval or abnormal morphology were referred to as pyknotic (Burkey et al. 2004, Kohn et al. 1995). To confirm the eccentric cytoplasmic localization and disintegration of nuclei, cells were incubated with the fluorescent nuclear stain Hoechst (1 µM, Invitrogen).

Neuronal apoptosis

Annexin V, an immunofluorescent marker, was used to distinguish neurons at an early apoptotic stage based on Annexin V-affinity to phosphatidylserine exposure at the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane (Johnson et al. 2004, Schutte et al. 1998). After 24 hr incubation with PMN, the cells were washed in cold PBS and re-suspended in Annexin V binding buffer (10 mM HEPES, 140 mM NaCl and 2.5 mM CaCl2 at pH of 7.4) followed by Annexin V conjugate (10 µl, 50 µg/ml, fluor 488 conjugate, Molecular Probes) for 15 min at room temperature. The cells were then washed with Annexin binding buffer prior to examination under a fluorescent microscope. Neurons with a positive Annexin V stain were counted within 5 different fields randomly selected and computed as percent of the total neuronal count in these same fields.

Intracellular calcium imaging

To visualize intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i) levels in DRG neurons, DRG cells in culture were loaded with a calcium indicator dye by rinsing in serum free HBSS (excluding phenol red) and incubation with fluo-4 AM (2.5 µM, Invitrogen) for 15 min at 37°C. The medium was then replaced with fresh HBSS, the cells were allowed to equilibrate for a further 5 min at 37°C and placed in a microscope stage incubator (20-20 Technology, Wilmington NC) to maintain a physiologic temperature. The microscope system consisted of a Nikon TE2000E inverted scope, with a 20x Plan Apo lens (0.75 NA), a high sensitivity, fast, cooled CCD camera (Roper Scientific CoolsnapHQ) and Prior excitation and emission filter wheels driven by MetaVue software (v6.2r2). Sequential green channel fluorescence (fluo-4) and a reference brightfield (DIC image) were collected every 5 sec for 20 min. The cells were imaged for 2–3 min to establish a baseline and different stimuli (100 µl PMN at E/T 10:1, equal volume HBSS or capsaicin, 100 µM, Sigma) were added by gentle pipetting. Regions of interest were defined around neurons under a brightfield and the cell diameter was computed. Fluorescence was quantified using MetaVue and the dataset was exported to a custom Perl application for further data processing. The fluorescence trace of each cell was analyzed for the occurrence of a ‘calcium response’ defined as peak (window size ±30 sec) in relative fluorescence intensity at least 10–15% greater than stable baseline level within 5 min of addition of various stimuli.

Whole cell recording

To test neuronal excitability, DRG cells were plated on 35 mm Petri dishes and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2. Small (20–25 µm) DRG neurons were used for current clamp recording 2–6 hours following tissue culture and after 30 min addition of isolectin B4 (IB4-FITC, 40 µg/ml; Sigma, St. Louis, MO), which allowed fluorescent labeling of a class of relatively non-peptidergic C-fiber nociceptors (Dirajlal et al. 2003, Saab et al. 2003). Electrodes were pulled from 1.6 mm O.D. borosilicate glass micropipettes (WPI, Sarasota, FL) and had a resistance of 1–2 MΩ when filled with the pipette solution, which contained (in mM): 140 KCl, 0.5 EGTA, 5 HEPES and 3 Mg-ATP (pH 7.3 with KOH, adjusted to 315 mOsm with dextrose). The extracellular solution contained (in mM): 140 NaCl, 3 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 HEPES (pH 7.3 with NaOH, adjusted to 320 mOsm with dextrose). Cells were maintained in a static bath of 1–2 ml and 30–50 µl PMN at E/T 10:1, PMN supernatant or equal volume bath solution was added directly to the bath. Changes in membrane potential were recorded with Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA), stored on a personal computer via a Digidata 1322a A/D converter and pClamp9 acquisition software (Molecular Devices) at an acquisition rate of 50 kHz with a lowpass Bessel filter setting of 5 kHz. Data acquisition began 3 min after establishing whole-cell configuration. Clampfit (Molecular Devices) and Origin (Microcal Software, Northhampton, MA) were used for data analysis. Whole-cell configuration was obtained in voltage-clamp mode before proceeding to the current-clamp recording mode. Only cells with stable (<10% variation) resting membrane potentials (RMP) more negative than −35 mV and overshooting action potentials (>85 mV RMP to peak) were used for further data collection. Input resistance was determined by the slope of a line fit to hyperpolarizing responses to current steps of 10–35 pA. Threshold was determined based on the first action potential elicited by a series of depolarizing current injections that increased in 5 pA increments. Frequency of firing was determined in response to 1 s depolarizing pulses starting at 50 pA and increasing in 50 pA intervals up to a maximum of 1000–1350 pA.

Statistical analysis

Two-tailed analyses were performed using parametric tests at the alpha significance level of 0.05. Statistical significance was computed using one-way ANOVA or three-way ANOVA for analysis of variation in firing frequency with time at increasing current intensities. Tests of factors including pair-wise comparisons were performed with either unpaired or paired Student’s t-test. In each cell loss experiment, PMN and DRG cells were obtained from 2 rats and co-incubated in at least 3 wells per treatment condition; each experiment was performed 3 times. For GFAP staining, 6 random fields containing 4–8 cells were obtained for each well. For calcium imaging, 4–8 cells were analyzed per field of view per well. For electrophysiology, 1 cell per well was analyzed before and after addition of PMN.

Results

PMN activation

Within 5 min of addition of PMN (200 µl, 106 cells/ml) to a microwell coated with poly-D-lysine, laminin and collagen, prepared similarly as used for plating DRG cells and containing DMEM-F12 (2 ml), less than 5% of cells were fluorescently labeled with CM-DCF (data not shown), indicating a very weak intracellular ROS activity and therefore, predominantly resting PMN. However, more than 90% of cells manifested a clear fluorescent signal 2 min after addition of PMA, indicating their viability and capacity for oxidative burst. In co-culture experiments, the majority of PMN added to DRG cells (E/T 10:1) were initially non-visible under fluorescence but became gradually fluorescent within 5–10 min afterwards. PMA added 10 min after PMN:DRG co-culture did not further increase the number of labeled cells.

Neuronal count

Relative to untreated DRG cultures (CT, 100%), neuronal counts after 24 hr co-culture with PMN at E/T ratios 0.2:1, 0.4:1, 5:1 and 10:1 decreased to 88% ± 12 (p>0.05), 55% ±22 (p<0.05), 58% ±9 (p<0.01) and 52% ±12 (p<0.01), respectively (Fig 1). Lidocaine addition concomitant with PMN at E/T 5:1 did not rescue neuronal count, which was not significantly different (72% ±11, p>0.05) compared to co-culture at similar E/T (58% ±9). Addition of TNFα did not significantly exacerbate neuronal loss (64% ±4, p>0.05) compared to co-cultures at similar E/T 10:1 (52% ±12). Treatment of DRG cells for 24 hr with supernatant collected from a different well after 24 hr co-culture at E/T 10:1 decreased neuronal count to 81% ±16 (p<0.05 compared to CT), whereas neuronal count did not significantly change after similar treatment with supernatant collected 15 min after co-culture or using fixed PMN at E/T 10:1 (data not shown). Interestingly, neuronal count was not different (p>0.05) from CT using MMA-treated PMN for the inhibition of iNOS at E/T 10:1 (102% ±38). To test for the effect of cell crowding, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were added with DRG cells for 24 hr at E/T 10:1, however, neuronal count was not significantly different than CT (99% ±8, p>0.05).

Fig 1.

Total neuronal count (mean ±SD) expressed as percentage of control (CT, untreated cultures) after 24 hr co-culture with PMN at different E/T ratios relative to DRG cells or co-culture with peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC, E/T 10:1). TNFα (activator of PMN) or lidocaine (blocker of sodium channels) was added in some cultures concomitantly with PMN (*p<0.05, **p<0.01 relative to CT), or PMN were treated with MMA (iNOS inhibitor) prior to co-culture with DRG cells.

Glial cell count and activation

Relative to untreated DRG cultures (CT, 100% ±30), the mean percent number of GFAP-positive cells after 24 hr co-culture with PMN at E/T ratio 10:1 did not change (112% ±38, Fig 2). However, mean fluorescence intensity in GFAP-positive cells increased from 16.8 ±3.6 in CT to 33.0 ±4.3 in PMN:DRG cocultures (p<0.05).

Fig 2.

Glial cell count (GFAP-positive cells) expressed as percent control (CT, untreated cultures) and GFAP immunofluorescence per cell relative to background (mean ±SD, *p<0.05). Compared to CT, co-culture of DRG cells with PMN at E/T 10:1 for 24 hr (B) did not change the mean number of GFAP-positive cells (C), but increased GFAP fluorescence (D) suggesting glial activation (For A–B, blue: nuclear DAPI; green: GFAP, horizontal bar= 20 µm).

Neuronal injury and apoptosis

Within 24 hr of plating followed by washing, the neuronal cytoplasm in untreated CT cultures was predominantly clear and delineated by a distinctly spherical and intact extracellular membrane (Fig 3a, arrow). Pyknotic neurons manifested several characteristics of cellular injury including ‘blebbing’ (Fig 4b). In addition, the nuclear stain revealed that the cell nucleus in pyknotic neurons was split and occupying an eccentric cytoplasmic location (Fig 3c). After co-incubation with PMN (E/T 10:1) for 24 hr, the total number of neurons with a pyknotic profile increased more than three fold (3.3 ±0.6, p<0.01 compared to CT, Fig 3, left lower panel). Furthermore, the percent neurons with Annexin V labeling (Fig 3d, e) increased by 14% at E/T 5:1 and by 35% at E/T 10:1 (30% ±6 and 51% ±12 respectively) compared to control (16% ±, Fig 4, right lower panel).

Fig 3.

PMN increase the number of pyknotic and apoptotic neurons in culture. Left panel: Number of pyknotic neurons (mean ±SD) expressed as fold increase compared to control (CT, untreated cultures) after 24 hr co-incubation with PMN at E/T 10:1. Note spherical neuronal soma with clearly delineated cytoplasmic membrane (a, arrow) compared to that of a pyknotic neuron with blebbing (b, arrow), granular cytoplasm and disintegrated nucleus evident by nuclear stain (c, arrow and arrowhead). Right panel: Number of neurons with Annexin V staining expressed as percentage of total neurons after 24 hr co-incubation with PMN E/T 5:1 or 10:1 (*p<0.05, **p<0.01 relative to CT). Photo in ‘d’ shows several DRG cells, same field is shown in ‘e’ with Annexin V fluorescence.

Fig 4.

PMN induce calcium responses in different subpopulations of DRG neurons. Total and percent numbers of neurons with calcium response within 15 min of co-incubation with PMN (E/T 10:1). Upper panel: Representative trace showing relative [Ca2+]i in a small size neuron; HBSS and PMN were added as indicated by arrowheads. Note robust and delayed calcium responses 2–3 minutes after addition of PMN. Lower panel: For each treatment, the number of neurons with increase in [Ca2+]i is represented by black histogram superimposed on white histogram showing total number of neurons, or separately (gray histogram) as percentage of total number of neurons.

Neuronal calcium transients

Relative neuronal [Ca2+]i showed a distinctive response in 25 out of 109 DRG cells with typical neuronal morphology (23%, Fig 4 lower panel) after co-incubation with PMN (E/T 10:1). In contrast, there was no noticeable change in [Ca2+]i after addition of equal volume HBSS (one example shown in Fig 4 upper panel). Calcium responses occurred typically 2–3 minutes after addition of PMN and lasted 1–3 min (hence referred to as calcium ‘transients’, Fig 4, upper panel). Of the small size (<25 µm diam) neurons 18/57 (31%) responded, and of the large size (>25 µm diam) neurons 7/52 (13%) responded. Furthermore, 4 out of 8 cells <25 µm diameter responding to PMN also responded to capsaicin and were presumably a subpopulation of capsaicin-sensitive nociceptors.

Neuronal excitability

Sixteen small size (<25 µm diam) IB4+ DRG neurons classified exclusively as C-nociceptor-type neurons (Fang et al. 2006) were selected for recording. Current threshold decreased from 298 ±48 pA to 197 ±41 pA within 4 min of PMN addition (Fig 5a, b, 11 cells), which also caused a gradual increase in neuronal firing frequency (Fig 5a, c), whereas the c(Fig 6d). In contrast, addition of bath solution or PMN supernatant did not change the current threshold, firing frequency or resting membrane potential (5 cells, data not shown).

Fig 5.

PMN increase the excitability of DRG neurons. Representative traces from one neuron (a) show membrane potential (resting potential −63 mV) in response to current pulses (pA), with upper trace showing one action potential at 400 pA (current threshold 200 pA) before addition of PMN (pre-PMN), whereas lower trace shows membrane potential (resting potential −56 mV) 4 min after PMN addition (post-PMN) with action potential burst at 150 pA or below baseline current threshold. Histograms (b) represent mean (±SD) current threshold in small diameter IB4+ neurons before and 4 min after addition of PMN (**p<0.01 relative to pre-PMN). In ‘c’, mean (±SD) firing frequency (Hz) of same neurons shown in ‘b’ before and 4 min after PMN versus stimulus intensities of increasing amplitudes (pA, *p<0.05 relative to pre-PMN). In ‘d’, mean (±SD) resting membrane potential (RMP, mV) in same neurons shown in ‘b,c’ before and at 1, 2 and 4 min after PMN addition.

Discussion

This study shows functional consequences of activated blood PMN on the viability, activity and excitability of DRG neurons. Using dissociated DRG neurons in culture, we demonstrate a significant decrease in neuronal count after co-incubation with activated PMN at a threshold E/T ratio between 0.2:1 and 0.4:1. Neuronal loss is probably unrelated to neuronal firing because lidocaine fails to abrogate this effect. The detrimental effect of PMN on neuronal viability does not necessarily require PMN contact with DRG cells as it can be mediated by co-culture supernatant. In support of our findings, a PMN-conditioned supernatant is sufficient to decrease the DRG neuronal count by approximately 50% (Nguyen et al. 2007). Moreover, few primary hippocampal neurons in vitro survive after 3 days co-incubation with PMN at E/T 0.5:1, and neuronal injury occurs in a cell-cell contact dependant manner (Dinkel et al. 2004). We speculate that the longer duration required for the manifestation of the neurotoxic effects observed by Dinkel and colleagues could be due to different culture assay techniques (non-dissociated slice preparation), resiliency of central versus peripheral neurons or activation level of PMN, which, in addition to the requirement for cellular contact warrant further investigation.

PMN at several fold higher E/T ratio (10:1) compared to neurotoxic threshold (<0.4:1) do not significantly aggravate neuronal loss, indicating a potential tolerance of peripheral neurons to high PMN levels. Information about physiological PMN titers in the nervous system under neuroinflammatory conditions is incomplete. In vivo, kainate-induced excitotoxicity causes rapid PMN infiltration into brain parenchyma estimated at E/T ratio 1:1 (Dinkel et al. 2004). In a rat model of painful sciatic neuropathy, the PMN count reaches a peak of approximately 280 cells in transverse sections of the sciatic nerve at midthigh lesion site 24 hr after injury (Perkins and Tracey 2000), whereas the entire rat’s sciatic nerve at midthigh is composed of about 27,000 axons (Schmalbruch 1986). However, we recently reported accumulation of PMN in lumbar DRG at E/T ratio 0.2:1 one week, but not 1 or 3 days after sciatic neuropathy (Morin et al. 2007). At a similar E/T ratio (0.2:1), by comparison, there is no significant neuronal loss in culture (this study) or in lumbar DRG within one week after sciatic lesion in vivo (Bailey and Ribeiroda-Silva 2006, Lekan et al. 1997, Tandrup et al. 2000). Therefore, we emphasize the importance of determining PMN count along the entire length of the injured nerve (or inflamed brain tissue volume) and at several time points following initial insult to quantify physiologically relevant PMN titers.

Our data also demonstrate prominent signs of neuronal injury and apoptosis following PMN co-incubation, indicating a major contribution of PMN to sub-lethal effects undetected by cellular count. Fluorometric calcium imaging and whole cell recording provide reliable and sensitive methods with optimal time resolutions for studying sub-lethal functional changes in neuronal activity and excitability. In this study, PMN-induced calcium transients suggest increased neuronal activity that is not limited to a specific class of sensory neurons based on cell-diameter distribution, and which specifically also occurred in a subpopulation of capsaicin-sensitive nociceptors. In rat, DRG neurons with a cell diameter <25 µm are predominately slowly conducting un-myelinated C fiber nociceptors, whereas larger size neurons are faster conducting mainly non-nociceptive Aδ or Aα/β (Fang et al. 2006). Most depolarizing electrical signals in neurons are associated with activation of different types of membrane channels, including voltage-gated calcium channels, allowing calcium influx, which can be further amplified by calcium release from intracellular stores (Berridge et al. 2000, Tsien 1988). Elucidating the intercellular signaling pathways triggered by calcium transients will offer insight into, and ways to modulate, the mechanisms underlying PMN-induced functional effects.

Based on the indication of PMN-induced neuronal activity, we studied the effect of PMN on neuronal excitability by measuring membrane voltage in a subpopulation of IB4-labeled nociceptive neurons. Within 5 min after exposure to PMN, neurons manifest a more depolarized firing threshold and an increased number of action potentials in response to injected current pulse. Hyperexcitability changes in DRG neurons, such as repetitive firing, have been documented in vivo following nerve damage, and have been shown to contribute to the pathophysiology of painful neuropathies (Amir et al. 2005, Devor 1999). Interestingly, systemic pretreatment with a non-specific selectin inhibitor to block PMN migration prevents paw mechanical hyperalgesia induced by subcutaneous 5-HT (Oliveira et al. 2007). Furthermore, selective and transient neutropenia delays thermal hyperalgesia following neuropathic sciatic transection (Perkins and Tracey 2000) and attenuates NGF-induced nociception (Bennett et al. 1998, Bennett 1999), as well as allergen-evoked nociception (Lavich et al. 2006). However, although pain is a common clinical complication of intradermal PMN accumulation (Heuft et al. 2004, Marchand et al. 2005), selective intradermal PMN recruitment by CXC chemokine ligands 1 and 2/3 does not induce mechanical allodynia or thermal hyperalgesia (Rittner et al. 2006, also see Cunha and Verri, 2006), in agreement with personal observations following intradermal PMN injection in the rat’s hindpaw. As emerging clinical data point to an association between neuropathic pain conditions and neuroinflammation (Watkins and Maier 2002), evidence that PMN might counteract inflammatory hyperalgesia by releasing opioid peptides should also be taken into consideration (Brack et al. 2004, Rittner et al. 2006).

Isolated PMN are predominantly “resting” but undergo rapid internal oxidative burst and activation within 5–10 min of co-incubation with DRG cells. We recently reported that circulating PMN in the rat are primed after neuropathic sciatic injury (Morin et al. 2007), however, the degree of activation of endoneurial PMN may be variable. Activated PMN release TNFα (Kobayashi et al. 2005, Nathan 2006, Segal 2005), which upon binding to its receptor expressed on sensory neurons causes membrane depolarization and pain (Schafers et al. 2003a,b, Song et al. 2003). In addition to TNFα, activated PMN release several mediators of cellular toxicity, including interleukin 1-beta (IL1β), IL2, IL6, matrix metalloproteinases (MMP), super oxide and other reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Kobayashi et al. 2005, Nathan 2006, Segal 2005), all considered potential candidates for mediating the functional neuronal effects. Nitric oxide synthase is inducible in rat PMN (Yui et al. 1991), and increased production of NO mediates neurotoxicity (Dawson et al. 1991, Lipton et al. 1993, Liu et al. 2002). In support of this argument, neuronal injury and apoptosis induced by PMN or a PMN-conditioned medium are partially mediated by proteases (Dinkel et al. 2004), TNFα, MMP-9, ROS (Nguyen et al. 2007) or NO pathways (this study). Moreover, increased expression of GFAP, a marker of DRG satellite cells and non-myelinating Schwanna cells (Peters et al. 2007), suggests activation of non-neuronal DRG cells in response to PMN. Further studies are required to assess the potential role glial cells might play in mediating or alleviating the PMN effects on neurons.

Overall, although co-culture assays do not completely reflect a directed immune reaction in vivo, our findings suggest that PMN can potentially aggravate neuronal injury and cause functional changes to peripheral sensory neurons. Distinguishing the beneficial from the detrimental effects of PMN on neurons, and identifying signaling mechanisms that allow immune cell recruitment to, interaction with, and influence on neuronal function may aid in the development of more effective drug therapies for neurological disorders involving neuroinflammation, including painful neuropathies.

Acknowledgements

Supported by funds from Rhode Island Hospital and Rhode Island Foundation (CYS), and by NCRR/NIH P20 RR018728 and Rhode Island Foundation (SKS). The authors thank Derek M. Kozikowski for conceptualizing and writing the software used to analyze calcium transients and Zachary Jaffa for rodent handling.

Abbreviation footnote

- DRG

Dorsal root ganglia

- E/T

effector/target cell ratio

- [Ca2+]i

intracellular calcium concentration

- PMN

polymorphonuclear leukocytes

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Amir R, Kocsis JD, Devor M. Multiple interacting sites of ectopic spike electrogenesis in primary sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2576–2585. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4118-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bailey AL, Ribeiro-da-Silva A. Transient loss of terminals from non-peptidergic nociceptive fibers in the substantia gelatinosa of spinal cord following chronic constriction injury of the sciatic nerve. Neuroscience. 2006;138:675–690. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett G, al-Rashed S, Hoult JR, Brain SD. Nerve growth factor induced hyperalgesia in the rat hind paw is dependent on circulating neutrophils. Pain. 1998;77:315–322. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00114-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennett GJ. Does a neuroimmune interaction contribute to the genesis of painful peripheral neuropathies? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:7737–7738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berridge MJ, Lipp P, Bootman MD. The versatility and universality of calcium signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:11–21. doi: 10.1038/35036035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brack A, Rittner HL, Machelska H, Leder K, Mousa SA, Schafer M, Stein C. Control of inflammatory pain by chemokine-mediated recruitment of opioid-containing polymorphonuclear cells. Pain. 2004;112:229–238. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burkey TH, Hingtgen CM, Vasko MR. Isolation and culture of sensory neurons from the dorsal-root ganglia of embryonic or adult rats. Methods Mol Med. 2004;99:189–202. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-770-X:189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y, Hallenbeck JM, Ruetzler C, Bol D, Thomas K, Berman NE, Vogel SN. Overexpression of monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 in the brain exacerbates ischemic brain injury and is associated with recruitment of inflammatory cells. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:748–755. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000071885.63724.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Connolly ES, Jr, Winfree CJ, Springer TA, Naka Y, Liao H, Yan SD, Stern DM, Solomon RA, Gutierrez-Ramos JC, Pinsky DJ. Cerebral protection in homozygous null ICAM-1 mice after middle cerebral artery occlusion. Role of neutrophil adhesion in the pathogenesis of stroke. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:209–216. doi: 10.1172/JCI118392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cunha TM, Verri WA., Jr. Neutrophils: are they hyperalgesic or anti-hyperalgesic? J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:727–728. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0406244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dawson VL, Dawson TM, London ED, Bredt DS, Snyder SH. Nitric oxide mediates glutamate neurotoxicity in primary cortical cultures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:6368–6371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.14.6368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Devor M. Unexplained peculiarities of the dorsal root ganglion. Pain Suppl. 1999;6:S27–S35. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dinkel K, Dhabhar FS, Sapolsky RM. Neurotoxic effects of polymorphonuclear granulocytes on hippocampal primary cultures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:331–336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0303510101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dirajlal S, Pauers LE, Stucky CL. Differential response properties of IB(4)-positive and -negative unmyelinated sensory neurons to protons and capsaicin. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:513–524. doi: 10.1152/jn.00371.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dirig DM, Salami A, Rathbun ML, Ozaki GT, Yaksh TL. Characterization of variables defining hindpaw withdrawal latency evoked by radiant thermal stimuli. J Neurosci Methods. 1997;76:183–191. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(97)00097-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dirnagl U, Iadecola C, Moskowitz MA. Pathobiology of ischaemic stroke: an integrated view. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:391–397. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01401-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dixon WJ. Efficient analysis of experimental observations. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1980;20:441–462. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.20.040180.002301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Djouhri L, Koutsikou S, Fang X, McMullan S, Lawson SN. Spontaneous pain, both neuropathic and inflammatory, is related to frequency of spontaneous firing in intact C-fiber nociceptors. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1281–1292. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3388-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dworkin RH, Backonja M, Rowbotham MC, et al. Advances in neuropathic pain: diagnosis, mechanisms, and treatment recommendations. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1524–1534. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.11.1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edwards SW, Hallett MB. Seeing the wood for the trees: the forgotten role of neutrophils in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol Today. 1997;18:320–324. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fang X, Djouhri L, McMullan S, Berry C, Waxman SG, Okuse K, Lawson SN. Intense isolectin-B4 binding in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons distinguishes C-fiber nociceptors with broad action potentials and high Nav 1.9 expression. J Neurosci. 2006;26:7281–7292. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1072-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heuft HG, Goudeva L, Blasczyk R. A comparative study of adverse reactions occurring after administration of glycosylated granulocyte colony stimulating factor and/or dexamethasone for mobilization of neutrophils in healthy donors. Ann Hematol. 2004;83:279–285. doi: 10.1007/s00277-003-0816-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang J, Kim LJ, Mealey R, Marsh HC, Jr, Zhang Y, Tenner AJ, Connolly ES, Jr, Pinsky DJ. Neuronal protection in stroke by an sLex-glycosylated complement inhibitory protein. Science. 1999;285:595–599. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5427.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson ME, Uhl CB, Spittler KH, Wang H, Gores GJ. Mitochondrial injury and caspase activation by the local anesthetic lidocaine. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:1184–1194. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200411000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kobayashi SD, Voyich JM, Burlak C, DeLeo FR. Neutrophils in the innate immune response. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2005;53:505–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kohn J, Minotti S, Durham H. Assessment of the neurotoxicity of styrene, styrene oxide, and styrene glycol in primary cultures of motor and sensory neurons. Toxicol Lett. 1995;75:29–37. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(94)03153-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lavich TR, Siqueira Rde A, Farias-Filho FA, Cordeiro RS, Rodrigues e Silva PM, Martins MA. Neutrophil infiltration is implicated in the sustained thermal hyperalgesic response evoked by allergen provocation in actively sensitized rats. Pain. 2006;125:180–187. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lavigne LM, O'Brien XM, Kim M, Janowski JW, Albina JE, Reichner JS. Integrin engagement mediates the human polymorphonuclear leukocyte response to a fungal pathogen-associated molecular pattern. J Immunol. 2007;178:7276–7282. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.7276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lekan HA, Chung K, Yoon YW, Chung JM, Coggeshall RE. Loss of dorsal root ganglion cells concomitant with dorsal root axon sprouting following segmental nerve lesions. Neuroscience. 1997;81:527–534. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00173-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lipton SA, Choi YB, Pan ZH, Lei SZ, Chen HS, Sucher NJ, Loscalzo J, Singel DJ, Stamler JS. A redox-based mechanism for the neuroprotective and neurodestructive effects of nitric oxide and related nitroso-compounds. Nature. 1993;364:626–632. doi: 10.1038/364626a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu B, Gao HM, Wang JY, Jeohn GH, Cooper CL, Hong JS. Role of nitric oxide in inflammation-mediated neurodegeneration. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;962:318–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lo EH, Dalkara T, Moskowitz MA. Mechanisms, challenges and opportunities in stroke. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:399–415. doi: 10.1038/nrn1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marchand F, Perretti M, McMahon SB. Role of the immune system in chronic pain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:521–532. doi: 10.1038/nrn1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moreno-Flores MT, Bovolenta P, Nieto-Sampedro M. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes in brain parenchyma after injury and their interaction with purified astrocytes in culture. Glia. 1993;7:146–157. doi: 10.1002/glia.440070204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morin N, Owolabi SA, Harty MW, Papa EF, Tracy TF, Jr, Shaw SK, Kim M, Saab CY. Neutrophils invade lumbar dorsal root ganglia after chronic constriction injury of the sciatic nerve. J Neuroimmunol. 2007;184:164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nathan C. Neutrophils and immunity: challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:173–182. doi: 10.1038/nri1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oliveira MC, Pelegrini-da-Silva A, Parada CA, Tambeli CH. 5-HT acts on nociceptive primary afferents through an indirect mechanism to induce hyperalgesia in the subcutaneous tissue. Neuroscience. 2007;145:708–714. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Owolabi SA, Saab CY. Fractalkine and minocycline alter neuronal activity in the spinal cord dorsal horn. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:4306–4310. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.06.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patterson AM, Schmutz C, Davis S, Gardner L, Ashton BA, Middleton J. Differential binding of chemokines to macrophages and neutrophils in the human inflamed synovium. Arthritis Res. 2002;4:209–214. doi: 10.1186/ar408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perkins NM, Tracey DJ. Hyperalgesia due to nerve injury: role of neutrophils. Neuroscience. 2000;101:745–757. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00396-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peters CM, Jimenez-Andrade JM, Jonas BM, Sevcik MA, Koewler NJ, Ghilardi JR, Wong GY, Mantyh PW. Intravenous paclitaxel administration in the rat induces a peripheral sensory neuropathy characterized by macrophage infiltration and injury to sensory neurons and their supporting cells. Exp Neurol. 2007;203:42–54. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prestigiacomo CJ, Kim SC, Connolly ES, Jr, Liao H, Yan SF, Pinsky DJ. CD18-mediated neutrophil recruitment contributes to the pathogenesis of reperfused but not nonreperfused stroke. Stroke. 1999;30:1110–1117. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.5.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Quinn MT, Gauss KA. Structure and regulation of the neutrophil respiratory burst oxidase: comparison with nonphagocyte oxidases. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76:760–781. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0404216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rittner HL, Mousa SA, Labuz D, Beschmann K, Schafer M, Stein C, Brack A. Selective local PMN recruitment by CXCL1 or CXCL2/3 injection does not cause inflammatory pain. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;79:1022–1032. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0805452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ryu JK, Tran KC, McLarnon JG. Depletion of neutrophils reduces neuronal degeneration and inflammatory responses induced by quinolinic acid in vivo. Glia. 2007;55:439–451. doi: 10.1002/glia.20479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saab CY, Cummins TR, Dib-Hajj SD, Waxman SG. Molecular determinant of Na(v)1.8 sodium channel resistance to the venom from the scorpion Leiurus quinquestriatus hebraeus. Neurosci Lett. 2002;331:79–82. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00860-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saab CY, Cummins TR, Waxman SG. GTP gamma S increases Nav1.8 current in small-diameter dorsal root ganglia neurons. Exp Brain Res. 2003;152:415–419. doi: 10.1007/s00221-003-1565-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schafers M, Geis C, Svensson CI, Luo ZD, Sommer C. Selective increase of tumour necrosis factor-alpha in injured and spared myelinated primary afferents after chronic constrictive injury of rat sciatic nerve. Eur J Neurosci. 2003a;17:791–804. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schafers M, Lee DH, Brors D, Yaksh TL, Sorkin LS. Increased sensitivity of injured and adjacent uninjured rat primary sensory neurons to exogenous tumor necrosis factor-alpha after spinal nerve ligation. J Neurosci. 2003b;23:3028–3038. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-03028.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schmalbruch H. Fiber composition of the rat sciatic nerve. Anat Rec. 1986;215:71–81. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092150111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schutte B, Nuydens R, Geerts H, Ramaekers F. Annexin V binding assay as a tool to measure apoptosis in differentiated neuronal cells. J Neurosci Methods. 1998;86:63–69. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(98)00147-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Segal AW. How neutrophils kill microbes. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:197–223. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Song XJ, Vizcarra C, Xu DS, Rupert RL, Wong ZN. Hyperalgesia and neural excitability following injuries to central and peripheral branches of axons and somata of dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:2185–2193. doi: 10.1152/jn.00802.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tandrup T, Woolf CJ, Coggeshall RE. Delayed loss of small dorsal root ganglion cells after transection of the rat sciatic nerve. J Comp Neurol. 2000;422:172–180. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000626)422:2<172::aid-cne2>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Taoka Y, Okajima K, Uchiba M, Murakami K, Kushimoto S, Johno M, Naruo M, Okabe H, Takatsuki K. Role of neutrophils in spinal cord injury in the rat. Neuroscience. 1997;79:1177–1182. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tsien RY. Fluorescence measurement and photochemical manipulation of cytosolic free calcium. Trends Neurosci. 1988;11:419–424. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(88)90192-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Watkins LR, Maier SF. Beyond neurons: evidence that immune and glial cells contribute to pathological pain states. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:981–1011. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00011.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yamasaki Y, Matsuo Y, Zagorski J, Matsuura N, Onodera H, Itoyama Y, Kogure K. New therapeutic possibility of blocking cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant on transient ischemic brain damage in rats. Brain Res. 1997;759:103–111. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00251-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang T, Zhang A, Honeggar M, Kohan DE, Mizel D, Sanders K, Hoidal JR, Briggs JP, Schnermann JB. Hypertonic induction of COX-2 in collecting duct cells by reactive oxygen species of mitochondrial origin. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:34966–34973. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502430200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yui Y, Hattori R, Kosuga K, Eizawa H, Hiki K, Ohkawa S, Ohnishi K, Terao S, Kawai C. Calmodulin-independent nitric oxide synthase from rat polymorphonuclear neutrophils. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:3369–3371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]