Abstract

TRPV6 is a member of the transient receptor potential superfamily of ion channels that facilitates Ca2+ absorption in the intestines. These channels display high selectivity for Ca2+, but in the absence of divalent cations they also conduct monovalent ions. TRPV6 channels have been shown to be inactivated by increased cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentrations. Here we studied the mechanism of this Ca2+-induced inactivation. Monovalent currents through TRPV6 substantially decreased after a 40-s application of Ca2+, but not Ba2+. We also show that Ca2+, but not Ba2+, influx via TRPV6 induces depletion of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P2 or PIP2) and the formation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate. Dialysis of DiC8 PI(4,5)P2 through the patch pipette inhibited Ca2+-dependent inactivation of TRPV6 currents in whole-cell patch clamp experiments. PI(4,5)P2 also activated TRPV6 currents in excised patches. PI(4)P, the precursor of PI(4,5)P2, neither activated TRPV6 in excised patches nor had any effect on Ca2+-induced inactivation in whole-cell experiments. Conversion of PI(4,5)P2 to PI(4)P by a rapamycin-inducible PI(4,5)P2 5-phosphatase inhibited TRPV6 currents in whole-cell experiments. Inhibiting phosphatidylinositol 4 kinases with wortmannin decreased TRPV6 currents and Ca2+ entry into TRPV6-expressing cells. We propose that Ca2+ influx through TRPV6 activates phospholipase C and the resulting depletion of PI(4,5)P2 contributes to the inactivation of TRPV6.

Calcium signaling orchestrates a myriad of physiological functions such as muscle contraction, neurotransmitter release, bone formation, and fertilization. Ca2+ entry through plasma membrane ion channels regulates numerous physiological and pathophysiological processes. The essential role of transient receptor potential (TRP)2 channel proteins in the regulation of cellular Ca2+ signaling has begun to be appreciated in the recent past (1–3). The mammalian TRP superfamily comprises six main subfamilies named the TRPC (canonical), TRPM (melastatin), TRPV (vanilloid), TRPP (polycystin), TRPML (mucolipin), and TRPA (ankyrin) groups. Among all TRP channels, TRPV5 and TRPV6, the members of the vanilloid subfamily, are the only ones that exhibit high Ca2+ selectivity (4).

TRPV6 is expressed in Ca2+-transporting epithelial cells, and it plays an important role in the active Ca2+ absorption by the intestines (5, 6). TRPV6 channels have been reported to be expressed in a variety of other tissues such as kidney, prostate, stomach, brain, and lung (7) and have also been shown to be expressed aberrantly in human malignancies (8). Until now no electrophysiological study has been performed characterizing these channels in native cells that express them endogenously. The physiological importance of these channels is understood from studies with genetically modified mice. Mice lacking TRPV6 have been shown to exhibit reduced intestinal Ca2+ reabsorption, increased urinary Ca2+ excretion, decreased bone density, reduced fertility, and skin abnormalities (9).

Electrophysiological characterization of TRPV6 channels in heterologous expression systems reveals that they exhibit strong inward rectification and reverse at positive potentials (10). They exhibit high Ca2+ selectivity and conduct monovalent cations in the absence of divalent cations. These monovalent currents through TRPV6 channels are much larger than those carried by Ca2+ at physiological Ca2+ concentrations (11, 12). Ca2+ that enters through TRPV6 or an increase in intracellular Ca2+ has been reported to cause inactivation of these channels (12–14). This also inactivates monovalent currents upon subsequent removal of extracellular Ca2+ (12). TRPV6 is also permeable to Ba2+, but Ba2+ influx induces less inactivation than Ca2+ or no inactivation at all depending on the conditions (12, 14). Recovery from Ca2+-induced inactivation is quite slow (12), and it was shown for the closely related TRPV5 that this recovery lags significantly behind restoration of cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels (15). TRPV6 channels were proposed to function as Ca2+ sensors, i.e. at low cytoplasmic [Ca2+] they open and let more Ca2+ in, and at high [Ca2+] they close and reduce further Ca2+ entry (10).

Recent evidence indicates that a growing number of mammalian TRP channels are functionally regulated by PI(4,5)P2 (16–18). Among the TRP proteins, seven are reported to be modulated by PI(4,5)P2. The Drosophila TRPL (19) was reported to be inhibited by PI(4,5)P2, whereas for TRPV1 both inhibition and activation were demonstrated (20–22). TRPV5 (23, 24), TRPM4 (25, 26), TRPM5 (27), TRPM7 (28, 29), and TRPM8 (23, 30) were reported to be activated by PI(4,5)P2.

In this study we examined the role of phosphoinositides in the Ca2+-induced inactivation of TRPV6. We demonstrate that the activity of TRPV6 depends on PI(4,5)P2, using different approaches including direct activation by PI(4,5)P2 in excised patches, dialyzing DiC8 PI(4,5)P2 via the patch pipette in whole-cell recordings, and dephosphorylating plasma membrane PI(4,5)P2 using a rapamycin-inducible PI(4,5)P2 5-phosphatase. We also show that Ca2+ flowing through TRPV6 activates phospholipase C (PLC), which leads to the depletion of PI(4,5)P2. Taken together, we provide evidence for a model that envisages the activation of PLC by Ca2+, which results in the hydrolysis of PI(4,5)P2, causing inactivation of TRPV6 channels.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Transfection—HEK293 cells were maintained in minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin. The human TRPV6 tagged with the Myc epitope on the N terminus, subcloned into the expression vector pCMV-Tag3A (Stratagene), was used for the experiments (31), and cells were transfected using the Effectene reagent. For the intracellular Ca2+ imaging and electrophysiology experiments, transfection was confirmed by measuring the fluorescence of co-transfected GFP. For experiments with rapamycin, the cells were transfected with the Myc-tagged TRPV6, the plasma membrane-targeted, CFP-tagged FRB, and the RFP-tagged FKBP12 linked to the phosphatase domain of PIP2 5-phosphatase (32). For control experiments, RFP-FKBP12-phosphatase domain was replaced with the RFP-tagged FKBP12 without the 5-phosphatase domain.

Mammalian Electrophysiology—Whole-cell patch clamp measurements were performed using a continuous holding protocol at –60 mV. Recordings were performed 36–72 h post-transfection in HEK293 cells using a bath solution containing, in mm, 137 NaCl, 5 KCl, 10 glucose, 10 HEPES, pH adjusted to 7.4 (designated as nominally divalent free, NDF). The same solution was used for the fluorescence measurements and Ca2+ imaging. Borosilicate glass pipettes (World Precision Instruments) of 2–4-megaohm resistance were filled with a solution containing, in mm, 135 potassium-gluconate, 5 KCl, 5 EGTA, 1 MgCl2, 2 ATP disodium, 10 HEPES, pH adjusted to 7.2. The cells were kept in NDF solution for 20 min before measurements. After formation of gigaohm resistance seals, whole-cell configuration was established and currents were measured using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments). Data were collected and analyzed with pCLAMP 9.0 software. All measurements were performed at room temperature, 20–25 °C. For experiments with wortmannin (WMN), cells expressing TRPV6 were preincubated with NDF containing 10 μm WMN for 30 min at room temperature. Control cells were treated with vehicle (DMSO) in NDF. All conditions and solutions remain the same for patch clamp, Ca2+ imaging, and fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) experiments unless otherwise specified.

Excised Patch Measurements in Xenopus Oocytes—Macropatch experiments were performed with borosilicate glass pipettes (World Precision Instruments) of 0.8–1.7-megaohm resistance. After establishing gigaohm resistance seals on devitellinized surfaces of Xenopus oocytes, inside-out configuration was established, and currents were measured using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments). The pipette solution contained, in mm, 96 LiCl, 1 EGTA, and 5 HEPES, pH 7.4. For the measurements in Fig. 3, the perfusion solution contained, in mm, 96 KCl, 5 EGTA, 10 HEPES, pH adjusted to 7.4. For the measurements shown in Fig. 7, the perfusion solution contained, in mm, 93 potassium gluconate, 5 HEDTA, 5 HEPES, pH 7.4. The free Ca2+ and Mg2+ concentrations were calculated using the MaxChelator program. To result in 10 μm free calcium, 3.85 mm Ca2+ was added (calcium-gluconate) and to result in 43 μm free Mg2+, we added 2.35 mm Mg2+ (magnesium-gluconate). For these measurements the bath was connected with the ground electrode through an agar bridge. Data were analyzed with pCLAMP 9.0 software (Axon Instruments) and plotted using Microcal Origin.

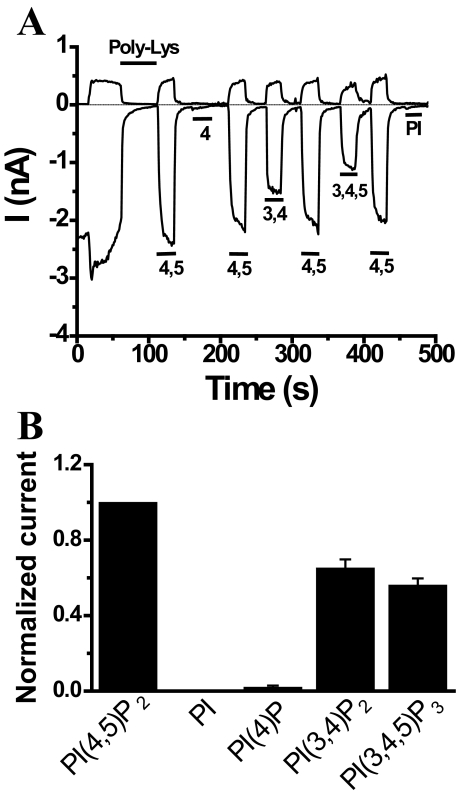

FIGURE 3.

PI(4,5)P2 activates TRPV6 in excised patches. Currents were measured in large membrane patches excised from Xenopus oocytes expressing TRPV6 using the ramp protocol from –100 to +100 mV applied every second (0.25 mV/ms). Representative traces show currents at +100 and –100 mV, upper and lower traces, respectively. Phosphoinositides were applied directly to the intracellular surface of the patch, as indicated by the horizontal bars. A, representative trace describing the effects of various phosphoinositides. To facilitate rundown, 30 μg/ml poly-lysine was added before the application of the phosphoinositides in two of six experiments; in the remaining experiments phosphoinositides were applied after spontaneous run down of the currents. The effects of phosphoinositides were indistinguishable in polylysine-treated and untreated patches, and thus the results were pooled. B illustrates statistics for –100 mV (n = 6) of the effects of different phosphoinositides compared with PI(4,5)P2. The average current ± S.E. for various phosphoinositides was normalized to PI(4,5)P2 responses. All phosphoinositides were short acyl chain (DiC8) applied at a concentration of 50 μm.

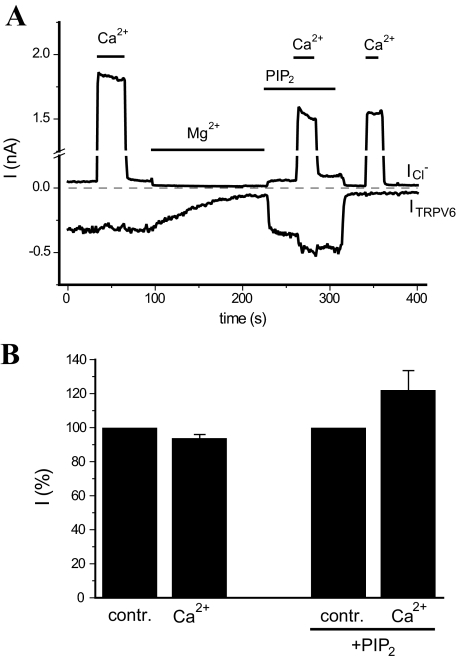

FIGURE 7.

The effect of Ca2+ on TRPV6 in excised patches. A, macroscopic currents were measured in excised patches from Xenopus oocytes expressing TRPV6, using the solutions described under “Experimental Procedures.” The applications of 10 μm free Ca2+, 43 μm free Mg2+, and 50 μm diC8 PI(4,5)P2 are indicated with horizontal lines. Holding potential was 0 mV, and then a 150-ms long step to –103 mV, followed by a step to +100 mV, was applied once every second. The changes at +100 mV mainly correspond to the Ca2+-activated Cl– currents (ICl–), whereas the changes at –103 mV correspond exclusively to TRPV6 currents. Note the lack of any current in response to Ca2+ at –103 mV after TRPV6 current rundown at the end of the experiment (third pulse of Ca2+). B, normalized current changes induced by Ca2+ at –103 mV (mean ± S.E., n = 8).

FRET Measurements—HEK293 cells were transfected with the CFP- and YFP-tagged PH domains of PLCδ1 and TRPV6. Measurements were performed using a Photon Technology International (PTI) (Birmingham, NJ) photomultiplier-based system mounted on an Olympus IX71 microscope, equipped with a DeltaRAM excitation light source. For the FRET measurements, excitation wavelength was 425 nm and emission was detected parallel at 480 and 535 nm using two interference filters and a dichroic mirror to separate the two emission wavelengths. Data were collected using the Felix software (PTI), and the ratio of traces obtained at the two different wavelengths correlating with FRET were plotted (33). Measurements were performed at room temperature (20–25 °C).

Inositol Phosphate Turnover—Measurements were performed similarly to that described in Ref. 34. HEK293 cells were transfected with either TRPV6-Myc and GFP or with GFP alone (controls) and incubated with 20 μCi of [3H]myo-inositol overnight in growth medium. Before the experiments the cells were kept in NDF for 20 min and for an additional 10 min in NDF containing 10 mm LiCl. Then the cells were treated with NDF containing no Ca2+ or 2 mm Ca2+ or 2 mm Ba2+ for 25–30 min in the continued presence of LiCl. The cells were scraped, treated with 4% perchloric acid, and centrifuged at 12000 rpm for 2–4 min. The supernatants (1.2 ml) were transferred into glass tubes containing 180 μl of 10 mm EDTA, pH 7.0, and to each tube 1.3 ml of a freshly prepared mixture of trioctylamine/Freon was added, vortexed, and centrifuged at 12000 rpm for 4 min. The top aqueous layer (∼1.2 ml) was transferred into plastic vials and 3.6 ml of sodium bicarbonate was added. This solution was then added to Dowex columns filled with AG1 × 8 resin (formate form). The columns were washed four times each with 5 ml of distilled water. Fractions 1–4 (5 ml each) 0.4 m ammonium formate/0.1 m formic acid, pH 4.75 (IP2 fraction); fractions 5–8 (5 ml each) 0.7 m ammonium formate/0.1 m formic acid, pH 4.75 (IP3 fraction); and fractions 9–12 (5 ml each) 1.2 m ammonium formate/0.1 m formic acid, pH 4.75 (IP4, IP5, and IP6 fraction) were collected. One ml of each of the collected fractions was transferred into a scintillation vial, 10 ml of scintillation mixture was added, and 3H activity was determined in a scintillation counter.

Ca2+ Imaging—Cells transfected with TRPV6 and GFP (marker for cell selection) were grown on 25-mm circular coverslips and loaded with fura-2 AM (2 μm) for 30–40 min at room temperature in NDF. The coverslips were then washed in NDF, placed in a stainless steel holder (bath volume, ∼0.8 ml; Molecular Probes), and viewed in a Zeiss Axiovert 100 microscope coupled to an Attofluor digital imaging system. Cells expressing GFP were selected and monitored simultaneously on each coverslip. Results are presented as the ratio (R) of fluorescence intensities at excitation wavelengths of 334 and 380 nm. Cells were continuously superfused with NDF, and Ca2+ entry was initiated by addition of a solution containing 2 mm CaCl2. All experiments were performed at room temperature.

Confocal Microscopy—HEK293 cells were transfected with TRPV6 and the GFP-tagged PLCδ1 PH domain (supplemental Fig. S1) or the components of the PI(4,5)P2 phosphatase recruitment system (supplemental Fig. S3). Experiments were performed 2 days after transfection. The cells were observed with a Zeiss LSM-510 confocal microscope in the Confocal Imaging Facility of the New Jersey Medical School. Images were saved as TIFF files and were analyzed with IMAGE J software.

Materials—Fura-2 AM was obtained from TefLabs (Austin, Texas). Effectene was obtained from Qiagen. Cell culture media, antibiotics, and sera were obtained from Invitrogen. DiC8 phosphoinositides were obtained from Cayman and Echelon. All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma.

Data Analysis—Data for all figures were expressed as mean ± S.E. Statistical significance was evaluated by Student's t test. * stands for p < 0.05, and ** for p < 0.001.

RESULTS

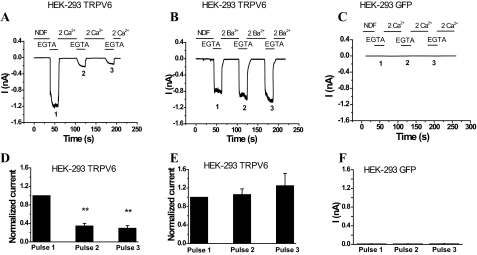

Ca2+, but Not Ba2+, Inactivates Na+ Currents through TRPV6—We studied the mechanism of Ca2+-induced inactivation of TRPV6 by measuring monovalent currents before and after exposing the TRPV6-expressing cells to Ca2+ (or Ba2+) -containing solutions in whole-cell configuration at a constant holding potential of –60 mV (Fig. 1). Monovalent currents were initiated by the application of a solution containing 2 mm EGTA and no added divalent ions. After a 40-s application of Ca2+, but not Ba2+, monovalent currents were markedly decreased despite the substantial entry of Ba2+ observed in fluorescence measurements (see Fig. 2D). The average current amplitude during the first pulse of 0 Ca2+ (EGTA) was 2.27 ± 0.65 nA, which was significantly higher than the second (0.86 ± 0.38 nA) and third (0.69 ± 0.27 nA) pulses. When Ba2+ was used instead of Ca2+, the average current amplitude for the first pulse was 1.87 ± 0.48 nA. The average current amplitudes for the second and third pulses were 1.83 ± 0.34 and 1.95 ± 0.32 nA, respectively. The same protocol did not induce any current in cells transfected with GFP (Fig. 1, C and F) or non-transfected HEK cells (data not shown). Monovalent currents through TRPV6 are also blocked by extracellular Mg2+ (11); thus we omitted Mg2+ from the extracellular NDF solution throughout the experiments.

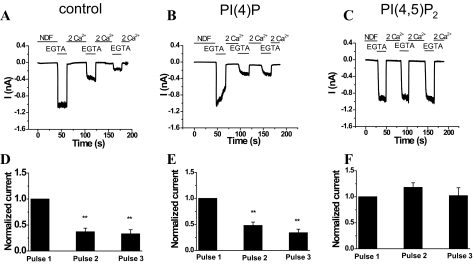

FIGURE 1.

Effects of Ca2+ and Ba2+ on monovalent currents of TRPV6 channels expressed in HEK293 cells. A and B, time courses of representative whole-cell recordings at a holding potential of –60 mV in HEK293 cells expressing GFP and TRPV6. Monovalent currents were initiated by the addition of NDF solution containing 2 mm EGTA for 20 s followed by addition of 2 mm Ca2+ or Ba2+ in NDF for 40 s. Note that the NDF solution at the beginning of the experiment has trace amounts of calcium in the low micromolar range that block monovalent currents through TRPV6. 1, 2, and 3 represent three alternating pulses of 0 Ca2+ (EGTA) and 2 mm Ca2+ or Ba2+. C, representative current trace in HEK cells expressing GFP, but not TRPV6. D and E, normalized average current amplitudes ± S.E. remaining before the addition of Ca2+ (n = 8) or Ba2+ (n = 8) normalized to the first pulse in TRPV6-expressing cells. **, p < 0.001. F, average current amplitudes evoked by pulses of EGTA in HEK cells expressing GFP alone.

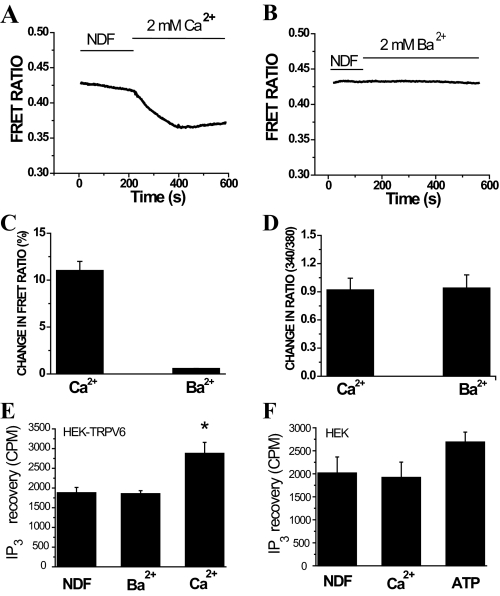

FIGURE 2.

Ca2+, but not Ba2+, induces PI(4,5)P2 hydrolysis in TRPV6-expressing cells. Fluorescence was measured in HEK293 cells expressing TRPV6 and the CFP- and YFP-tagged PLCδ1 PH domains as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Cells were kept in NDF solution for 20 min before the experiment. During the measurement, 2 mm Ca2+ or Ba2+ was added at 200 s. A and B represent the time courses of FRET ratio for Ca2+ and Ba2+, respectively. C represents the mean ± S.E. for change in FRET ratio signals, calculated the following way. We divided the value 2 min after the addition of 2 mm Ca2+ (n = 5) or Ba2+ (n = 5) by the value before addition of Ca2+ to result in F and then 100 – (100 × F) was plotted. D represents the mean of change in 340/380 nm ratio ± S.E. for Ca2+ (n = 31) or Ba2+ (n = 36) in fura-2-loaded cells expressing TRPV6. E, IP3 measurement in TRPV6-expressing HEK-293 cells in response to 2 mm Ca2+ or Ba2+.*, p < 0.05. F, IP3 measurement in non-transfected HEK293 cells in response to 2 mm Ca2+ and in response to 100 μm extracellular ATP. Error bars represent average ± S.E.

Ca2+, but Not Ba2+, Influx through TRPV6 Channels Reduces PI(4,5)P2 Levels—Ca2+ influx through TRPM8 channels has been suggested to induce PI(4,5)P2 depletion via PLC activation (23). To explore the mechanism of the differential behavior of Ca2+ and Ba2+ on the inactivation of TRPV6 channels, we used a FRET-based technique (23, 33) to show that Ca2+, but not Ba2+, induces depletion of PI(4,5)P2 (Fig. 2, A and B). This technique is based on the translocation of the CFP/YFP-tagged PLCδ1 PH domains from the plasma membrane to the cytoplasm upon PIP(4,5)2 depletion, which is shown in the figure as downward deflection of the FRET ratio traces. This technique has been shown to display good correlation with translocation of the GFP-tagged PLCδ1 PH domain as measured with confocal microscopy (33). We also show that Ca2+ induces translocation of the GFP-tagged PLCδ1 PH domain using confocal microscopy (supplemental Fig. S1). Fig. 2C summarizes the percentage of change in FRET ratio caused by addition of 2 mm Ca2+ or Ba2+. Fig. 2D shows that addition of 2 mm Ca2+ or Ba2+ resulted in similar change in the fluorescence ratio of fura-2-loaded TRPV6 cells, indicating that both Ca2+ and Ba2+ enter through these channels.

We have also measured IP3 production in HEK cells in response to Ca2+ and Ba2+ influx through TRPV6. Fig. 2E shows that IP3 production is increased in HEK cells expressing TRPV6 in response to the application of Ca2+, but not Ba2+. HEK cells not expressing TRPV6 did not respond with increased formation of IP3 to the application of Ca2+ (Fig. 2F), but they responded to extracellular ATP, which activates PLC in these cells via P2Y cell surface receptors (35). Supplemental Fig. S2 shows that application of extracellular Ca2+ in HEK293 cells not expressing TRPV6 did not significantly increase cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels and did not induce any changes in FRET, demonstrating that Ca2+ entry and Ca2+-induced PI(4,5)P2 hydrolysis depend on the presence of TRPV6 channels.

PI(4,5)P2, but Not PI(4)P, Activates TRPV6 Channels and Prevents Ca2+-induced Inactivation—We next examined the direct effects of phosphoinositides on TRPV6 channels. We studied the effects of short acyl chain (diC8) analogues (36) of various phosphoinositides in excised patches of Xenopus oocytes expressing TRPV6 (Fig. 3, A and B). PI(4,5)P2, but not PI or PI(4)P, activated TRPV6 channels in excised patches. PI(3,4)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3, the products of phosphoinositide 3 kinases, also activated TRPV6, but their effects were smaller than that of PI(4,5)P2 (Fig. 3, A and B).

In whole-cell patch clamp experiments, dialysis of DiC8 PI(4,5)P2 via the patch pipette relieved TRPV6 currents from Ca2+-induced inactivation (Fig. 4C), whereas DiC8 PI(4)P had no effect (Fig. 4B). Control cells (Fig. 4, A and D) had current amplitudes of 1.44 ± 0.45 (first pulse), 0.49 ± 0.1 (second pulse), and 0.44 ± 0.12 nA (third pulse). The amplitude of the monovalent currents in cells dialyzed with DiC8 PI(4)P (Fig. 4, B and E) were 1.65 ± 0.35, 0.48 ± 0.16, and 0.34 ± 0.1 nA for the first, second, and third pulses, respectively. In cells dialyzed with DiC8 PI(4,5)P2 (Fig. 4, C and F), the current amplitude for the first pulse was 1.1 ± 0.14, for the second pulse it was 1.18 ± 0.17, and it was 1.16 ± 0.18 nA for the third pulse.

FIGURE 4.

PI(4,5)P2, but not PI(4)P, prevents Ca2+-induced inactivation of TRPV6 channels in HEK293 cells. A–C represent the time courses of whole-cell TRPV6 currents in control (n = 9), PI(4)P (n = 7), or PI(4,5)P2 (n = 9) dialyzed cells recorded at a constant holding potential of –60 mV. Recordings were performed 5–10 min after the formation of whole-cell configuration. Short acyl chain (DiC8) PI(4)P or PI(4,5)P2 at a concentration of 50 μm were dialyzed through the patch pipette. D–F represent the average current amplitudes ± S.E. normalized to the peak of the first pulse of 0 Ca2+ in control, PI(4)P, and PI(4,5)P2 dialyzed cells, respectively. **, p < 0.001.

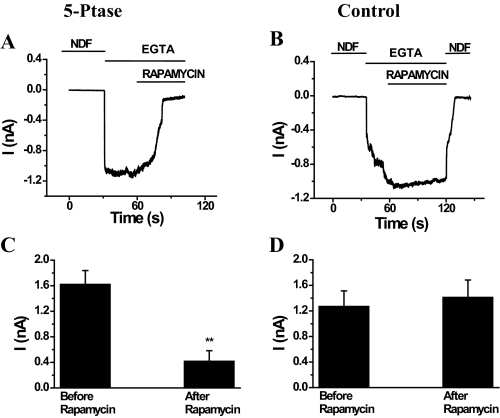

Dephosphorylation of PI(4,5)P2 by a PI(4,5)P2 5-Phosphatase Inhibits TRPV6 Channels—Next we tested the effect of depletion of PI(4,5)P2 by alternate means that do not involve a rise in intracellular [Ca2+]. For this, we employed the recently developed rapamycin-inducible PI(4,5)P2 5-phosphatase to deplete PI(4,5)P2 in TRPV6-expressing cells (Fig. 5). This technique is based on the translocation of the phosphatase domain of the PI(4,5)P2 5-phosphatase to the plasma membrane induced by rapamycin, which was shown to cause depletion of PI(4,5)P2 and inhibition of TRPM8 (32) and KCNQ2/3 channels (37). Rapamycin (100 nm) inhibited the whole-cell monovalent currents through TRPV6 channels expressing the rapamycin-inducible PI(4,5)P2 5-phosphatase constructs (Fig. 5A) and had no effect in parallel controls (Fig. 5B). Supplemental Fig. S3 shows the translocation of the RFP-tagged PI(4,5)P2 phosphatase to the plasma membrane.

FIGURE 5.

Translocation of the PI(4,5)P2 5-phosphatase to the plasma membrane inhibits TRPV6. HEK293 cells were transfected with TRPV6 and the CFP-tagged FRB and either the RFP-tagged FKBP12 fused to the phosphatase domain of the PIP2 5-phosphatase (5′-Ptase) or the RFP-tagged FKBP12 (Control). Whole-cell recordings were performed at a constant holding potential of –60 mV in NDF solution. Monovalent currents were initiated with NDF solution containing 2 mm EGTA. Translocation of the phosphatase domain was induced by the addition of 100 nm rapamycin. A and B represent the time course of monovalent currents in TRPV6 cells at a holding potential of –60 mV before and after addition of 100 nm rapamycin in 5-phosphatase and control cells, respectively. C and D represent the mean ± S.E. of current values 30 s after initiation of monovalent current by the addition of 0 Ca2+ (EGTA) solution and 30 s after the addition of rapamycin in 5-phosphatase (n = 9) or control (n = 10) cells, respectively. **, p < 0.001.

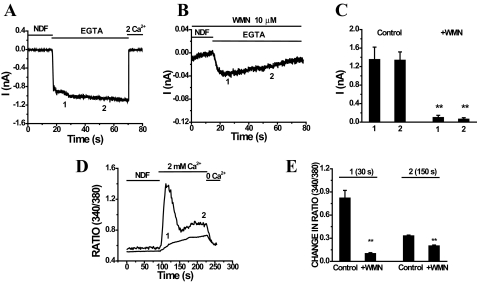

WMN Inhibits TRPV6 Channels—WMN at high concentrations inhibits some isoforms of phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase (38). WMN was reported to deplete PI(4,5)P2 in intact cells and inhibit PI(4,5)P2-sensitive ion channels (39, 40). We found that preincubation with 10 μm WMN for 30 min significantly inhibited TRPV6 currents compared with untreated controls (Fig. 6, A–C). We measured the currents at two different time points to compare the peak and the sustained TRPV6 currents in WMN-treated cells and vehicle-treated controls. In control cells (Fig. 6A), the average currents at the end of 10 and 40 s were 1.35 ± 0.27 and 1.34 ± 0.18 nA, respectively, whereas in WMN-treated cells (Fig. 6B) the current remaining at the end of 10 s was 0.098 ± 0.048 nA and at the end of 40 s was 0.063 ± 0.032 nA. Interestingly, WMN-treated cells (four of the six cells) showed slow inactivation of currents even in the absence of extracellular Ca2+. Treatment of cells with 10 μm WMN for a shorter duration of time (10 min) did not result in consistent inhibition of TRPV6 currents (data not shown).

FIGURE 6.

Wortmannin (WMN) inhibits monovalent currents as well as Ca2+ entry through TRPV6 channels. A and B represent the time courses of whole-cell TRPV6 currents measured in control and WMN-pretreated (10 μm for 30 min) cells at a constant holding potential of –60 mV. C, normalized whole-cell monovalent currents are shown for control and WMN-pretreated cells. The mean currents ± S.E. were measured at two time points (1 and 2) and represent control (n = 8) and WMN-pretreated (n = 6) cells. D represents the time courses of changes in the ratio of fura-2 fluorescence upon addition of 2 mm Ca2+ in WMN-pretreated cells and untreated controls. E, the average change in fluorescence ratio ± S.E. for the control (n = 32) and WMN-pretreated (n = 66) cells measured at two time points, 1 and 2, representing 30 and 150 s after initiation of Ca2+ entry was plotted. **, p < 0.001.

To further confirm the effect of WMN, we measured intracellular Ca2+ in cells expressing TRPV6. Treatment of cells with 10 μm WMN for 30 min inhibited Ca2+ entry significantly compared with untreated controls (Fig. 6D). Fig. 6E summarizes the change in fluorescence ratio in control and WMN-treated cells measured at two different time points of 30 and 150 s after the addition of Ca2+.

Protein Kinase C Activation Does Not Affect TRPV6 Channel Activity—Protein kinase C is also generally activated upon PLC activation, and Ca2+-dependent protein kinase C activation has been suggested to mediate menthol-induced desensitization of TRPM8 (41, 42). To test the effect of protein kinase C, we examined the effect of 1-oleoyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol, a cell-permeable diacylglycerol analogue. 1-Oleoyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol (100 μm) failed to inhibit monovalent currents through TRPV6 measured at –60 mV, and it also failed to affect Ca2+ signals in TRPV6-expressing cells (data not shown).

Direct Application of Ca2+ to Excised Patches Has Only a Negligible Effect on TRPV6—Finally, we tested the effects of direct application of Ca2+ (10 μm) on TRPV6 in excised patches. These measurements were performed in Xenopus oocytes, which endogenously express a Ca2+-activated Cl– current. We could not fully inhibit these channels with niflumic acid or flufenamic acid (43) at 300 μm. Higher concentrations of these agents inhibited TRPV6 currents (data not shown).

Thus, we circumvented this problem by detecting TRPV6 currents at the reversal potential of the chloride current the following way. For the bath solution (cytoplasmic) we used a gluconate-based Cl–-free solution, and the pipette solution (extracellular) contained Cl– as the main anion (see “Experimental Procedures” for details). The Ca2+-activated Cl– channels have a small but detectable permeability to gluconate (44); thus, we found that the reversal potential of the Cl– (gluconate) currents under these conditions was –103 mV. At this potential we could measure TRPV6 currents, whereas we could monitor the chloride currents at +100 mV (Fig. 7). We applied 10 μm free Ca2+ (buffered with HEDTA) shortly after excision, where it induced only a negligible inhibition of TRPV6 currents (Fig. 7A). As the currents under these conditions exhibited a variable level of rundown (see also Fig. 3), we also applied Ca2+ after the channels were re-activated with 50 μm diC8 PI(4,5)P2 (Fig. 7). Under these conditions 10 μm Ca2+ slightly potentiated TRPV6 currents, but this effect was variable and not statistically significant (p = 0.094, n = 8).

To induce uniform rundown of TRPV6 currents in all experiments, we applied Mg2+ (43 μm free Mg2+) to the excised patches before reactivating TRPV6 with PI(4,5)P2. Mg2+ serves as a cofactor for lipid phosphatases and thus promotes depletion of PI(4,5)P2 (45) that leads to current rundown. Mg2+ also has a direct inhibitory effect on TRPV6 (11), which is mainly prevalent at positive voltages at this concentration; note the fast inhibition of the outward currents in Fig. 7. After the washout of diC8 PI(4,5)P2 when TRPV6 currents completely disappeared, we applied a third pulse of Ca2+ in each measurement to confirm the absence of Cl– current at –103 mV. We conclude that direct binding of Ca2+ to the cytosolic surface of TRPV6 is unlikely to significantly contribute to the marked Ca2+-induced inactivation we observe in whole-cell patch clamp measurements.

DISCUSSION

Ca2+-induced Inactivation of TRPV6—TRPV6 is a constitutively active Ca2+-selective channel that mediates Ca2+ uptake through the apical membrane of epithelial cells (4). When Ca2+ enters the cells through these channels, they inactivate, which is mediated by an increase in cytoplasmic [Ca2+]. This Ca2+-induced inactivation may play a role as a feedback loop to regulate cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels, preventing Ca2+ overload through these channels (10). This Ca2+-induced inactivation has been shown to consist of a fast and a slower component when studied by activating the channels with fast voltage steps to negative membrane potentials (12–14). Recovery from this Ca2+-induced inactivation is quite slow (12), suggesting either a process with a very slow off rate or a need for the resynthesis of a cofactor that is lost during the inactivation process.

Most earlier studies examined Ca2+-induced inactivation at relatively high extracellular Ca2+ concentrations (≥10 mm) and on a relatively short time scale (1–2 s), and Ca2+ entry was initiated by a short voltage pulse to negative membrane potentials (12, 13). Our study focused on the effects of steady-state Ca2+ entry at a constant holding potential on a longer time scale (min), as this presumably resembles the native conditions of these channels in epithelial cells. In patch clamp experiments we measured monovalent currents through TRPV6 because these are much easier to detect than the much smaller Ca2+ currents in physiological extracellular Ca2+ concentrations. We show that under these conditions TRPV6 channels undergo inactivation when conducting Ca2+, but not Ba2+, which is consistent with earlier findings using different protocols (14).

We show that PI(4,5)P2 is depleted in response to application of extracellular Ca2+, but not Ba2+, in cells expressing TRPV6. We also show that Ca2+, but not Ba2+, stimulates the formation of IP3 in TRPV6-expressing cells; thus, it is likely that the mechanism of PI(4,5)P2 depletion is the Ca2+-induced activation of PLC. The lack of effect of Ba2+ on PI(4,5)P2 depletion and IP3 formation is consistent with earlier findings showing that PLC activation, as measured by the sustained phase of IP3 production, was significantly reduced in angiotensin-2-stimulated adrenal glomerulosa cells when Ca2+ was replaced with Ba2+ in the extracellular medium (46).

The Role of Phosphoinositides in the Regulation of TRPV6—The activation of PLC leads to a multitude of events, such as formation of IP3 and other soluble inositol phosphates, Ca2+ release from intracellular stores, the activation of protein kinase C, and reduction of plasma membrane PI(4,5)P2 levels. Many TRP channels need PI(4,5)P2 for activity; thus, PI(4,5)P2 depletion is an attractive candidate to mediate the inactivation of TRPV6. We have shown here that dialyzing PI(4,5)P2 through the patch pipette essentially eliminated the Ca2+-induced inactivation of TRPV6. This is compatible with the inactivation being mediated by PI(4,5)P2 depletion, and it is incompatible with the role of all other candidates, because supplying more substrate for PLC would presumably increase the formation of all the other messengers. Our negative control was PI(4)P, which, unlike PI(4,5)P2, did not activate TRPV6 in excised patches and did not inhibit Ca2+-induced inactivation of TRPV6. We have also shown that activation of protein kinase C with the diacylglycerol analogue 1-oleoyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol did not inhibit TRPV6, confirming that Ca2+-induced inactivation is not mediated by protein kinase C. We also did not detect substantial inhibition by Ca2+ in excised patches; thus, it is unlikely that direct binding of Ca2+ to cytoplasmic parts of the channel significantly contributes to Ca2+-induced inactivation.

We have shown that PI(4,5)P2 depletion is necessary for Ca2+-induced inactivation of TRPV6, but is it sufficient to inhibit these channels? To test this, we have utilized two different tools to decrease membrane PI(4,5)P2 levels without activating PLC and thus not forming IP3 and diacylglycerol. First we used the recently described rapamycin-inducible PI(4,5)P2 5-phosphatase recruitment system to selectively deplete PI(4,5)P2 by converting it to PI(4)P (32). Rapamycin-induced PI(4,5)P2 depletion inhibited TRPV6 currents, which is compatible with the role of PI(4,5)P2 keeping this channel open and the lack of ability of PI(4)P to activate it. To confirm these data, we have also utilized wortmannin at concentrations where it inhibits phosphoinositol 4 kinases thus inhibiting the supply of the precursor of PI(4,5)P2, leading to slow depletion of PI(4,5)P2. Wortmannin inhibited both TRPV6 currents and Ca2+ signals in TRPV6-expressing cells. These data together demonstrate that depletion of PI(4,5)P2 is sufficient to inhibit TRPV6.

PI(3,4)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3, the products of phosphatidyl inositol 3 kinase, also activated TRPV6 in excised patches even though they were less effective than PI(4,5)P2. These lipids are thought to be at lower concentrations in the plasma membrane than PI(4,5)P2 (47), and thus their effects are probably overridden by the latter.

In summary, our data demonstrate that TRPV6 channels require PI(4,5)P2 for activity and that the hydrolysis of this lipid by Ca2+-induced activation of PLC contributes to inactivation of this channel. This mechanism may serve as a feedback loop for the regulation of TRPV6, allowing this channel to function asaCa2+ sensor and thus regulate cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. J. P. Reeves for insightful comments on the manuscript and for kind permission to use the Ca2+-imaging setup in the Reeves laboratory. We also thank Dr. A. P. Thomas for valuable discussion and Dr. Lawrence Gaspers for help with the IP3 measurements. The clone for the human TRPV6 was generously provided by Dr. T. V. McDonald (Albert Einstein College of Medicine). The clones for the PIP2 5-phosphatase recruitment system were provided by Dr. Tamas Balla (National Institutes of Health).

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant NS055159. This work was also supported by the American Heart Association, the Alexander and Alexandrine Sinsheimer Foundation, and the UMDNJ Foundation (all to T. R.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: TRP, transient receptor potential; CFP, cyan fluorescent protein; HEDTA, N-(2-hydroxyethyl)ethylenediamine-N,N′,N′-tri-acetic acid; FRET, fluorescence resonance energy transfer; GFP, green fluorescent protein; IP3, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate; RFP, red fluorescent protein; NDF, nominally divalent free; PI(4,5)P2, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate; PI(4)P, phosphatidylinositol 4-monophosphate; PI(3,4,5)P3, phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate; PI(3,4)P2, phosphatidylinositol 3,4-bisphosphate; PLC, phospholipase C; WMN, wortmannin; YFP, yellow fluorescent protein; HEK, human embryonic kidney; PH domain, pleckstrin homology domain.

References

- 1.Montell, C. (2005) Sci. STKE 2005 re3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nilius, B., Owsianik, G., Voets, T., and Peters, J. A. (2007) Physiol. Rev. 87 165–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clapham, D. E. (2003) Nature 426 517–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoenderop, J. G., Nilius, B., and Bindels, R. J. (2005) Physiol. Rev. 85 373–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vennekens, R., Voets, T., Bindels, R. J., Droogmans, G., and Nilius, B. (2002) Cell Calcium 31 253–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoenderop, J. G., Nilius, B., and Bindels, R. J. (2002) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 64 529–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nijenhuis, T., Hoenderop, J. G., van der Kemp, A. W., and Bindels, R. J. (2003) J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 14 2731–2740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhuang, L., Peng, J. B., Tou, L., Takanaga, H., Adam, R. M., Hediger, M. A., and Freeman, M. R. (2002) Lab. Investig. 82 1755–1764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bianco, S. D., Peng, J. B., Takanaga, H., Suzuki, Y., Crescenzi, A., Kos, C. H., Zhuang, L., Freeman, M. R., Gouveia, C. H., Wu, J., Luo, H., Mauro, T., Brown, E. M., and Hediger, M. A. (2006) J. Bone Miner. Res. 22 274–285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bodding, M., Wissenbach, U., and Flockerzi, V. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 36656–36664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Voets, T., Janssens, A., Prenen, J., Droogmans, G., and Nilius, B. (2003) J. Gen. Physiol. 121 245–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoenderop, J. G., Vennekens, R., Muller, D., Prenen, J., Droogmans, G., Bindels, R. J., and Nilius, B. (2001) J. Physiol. 537 747–761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nilius, B., Prenen, J., Hoenderop, J. G., Vennekens, R., Hoefs, S., Weidema, A. F., Droogmans, G., and Bindels, R. J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 30852–30858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Derler, I., Hofbauer, M., Kahr, H., Fritsch, R., Muik, M., Kepplinger, K., Hack, M. E., Moritz, S., Schindl, R., Groschner, K., and Romanin, C. (2006) J. Physiol. 577 31–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nilius, B., Prenen, J., Vennekens, R., Hoenderop, J. G., Bindels, R. J., and Droogmans, G. (2001) Cell Calcium 29 417–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rohacs, T. (2007) Pflugers Arch. Euc. J. Physiol. 453 753–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Voets, T., and Nilius, B. (2007) J. Physiol. 582 939–944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hardie, R. C. (2007) J. Physiol. 578 9–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Estacion, M., Sinkins, W. G., and Schilling, W. P. (2001) J. Physiol. 530 1–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chuang, H. H., Prescott, E. D., Kong, H., Shields, S., Jordt, S. E., Basbaum, A. I., Chao, M. V., and Julius, D. (2001) Nature 411 957–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stein, A. T., Ufret-Vincenty, C. A., Hua, L., Santana, L. F., and Gordon, S. E. (2006) J. Gen. Physiol. 128 509–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lukacs, V., Thyagarajan, B., Balla, A., Varnai, P., Balla, T., and Rohacs, T. (2007) J. Neurosci. 27 7070–7080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rohacs, T., Lopes, C. M. B., Michailidis, I., and Logothetis, D. E. (2005) Nat. Neurosci. 8 626–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee, J., Cha, S. K., Sun, T. J., and Huang, C.-L. (2005) J. Gen. Physiol. 126 439–451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nilius, B., Mahieu, F., Prenen, J., Janssens, A., Owsianik, G., Vennekens, R., and Voets, T. (2006) EMBO J. 25 467–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang, Z., Okawa, H., Wang, Y., and Liman, E. R. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 39185–39192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu, D., and Liman, E. R. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100 15160–15165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Runnels, L. W., Yue, L., and Clapham, D. E. (2002) Nat. Cell Biol. 4 329–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gwanyanya, A., Sipido, K., Vereecke, J., and Mubagwa, K. (2006) Am. J. Physiol. 291 C627–C635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu, B., and Qin, F. (2005) J. Neurosci. 25 1674–1681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cui, J., Bian, J. S., Kagan, A., and McDonald, T. V. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 47175–47183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Varnai, P., Thyagarajan, B., Rohacs, T., and Balla, T. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 175 377–382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van der Wal, J., Habets, R., Varnai, P., Balla, T., and Jalink, K. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 15337–15344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rooney, T. A., Hager, R., and Thomas, A. P. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266 15068–15074 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fischer, W., Franke, H., Groger-Arndt, H., and Illes, P. (2005) Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 371 466–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rohacs, T., Chen, J., Prestwich, G. D., and Logothetis, D. E. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274 36065–36072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suh, B. C., Inoue, T., Meyer, T., and Hille, B. (2006) Science 314 1454–1457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Balla, A., and Balla, T. (2006) Trends Cell Biol. 16 351–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Czirjak, G., Petheo, G. L., Spat, A., and Enyedi, P. (2001) Am. J. Physiol. 281 C700-C708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang, H., Craciun, L. C., Mirshahi, T., Rohacs, T., Lopes, C. M. B., Jin, T., and Logothetis, D. E. (2003) Neuron 37 963–975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abe, J., Hosokawa, H., Sawada, Y., Matsumura, K., and Kobayashi, S. (2006) Neurosci. Lett. 397 140–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Premkumar, L. S., Raisinghani, M., Pingle, S. C., Long, C., and Pimentel, F. (2005) J. Neurosci. 25 11322–11329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.White, M. M., and Aylwin, M. (1990) Mol. Pharmacol. 37 720–724 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qu, Z., and Hartzell, H. C. (2000) J. Gen. Physiol. 116 825–844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang, C. L., Feng, S., and Hilgemann, D. W. (1998) Nature 391 803–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Balla, T., Nakanishi, S., and Catt, K. J. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269 16101–16107 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fruman, D. A., Meyers, R. E., and Cantley, L. C. (1998) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67 481–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.