Abstract

The human immunodeficiency virus, type 1 (HIV-1), gp41 core plays an important role in fusion between viral and target cell membranes. We previously identified an HIV-1 gp41 core-binding motif HXXNPF (where X is any amino acid residue). In this study, we found that Asn, Pro, and Phe were the key residues for gp41 core binding. There are two NPF motifs in Epsin-1-(470–499), a fragment of Epsin, which is an essential accessory factor of endocytosis that can dock to the plasma membrane by interacting with the lipid. Epsin-1-(470–499) bound significantly to the gp41 core formed by the polypeptide N36(L8)C34 and interacted with the recombinant soluble gp41 containing the core structure. A synthetic peptide containing the Epsin-1-(470–499) sequence could effectively block entry of HIV-1 virions into SupT1 T cells via the endocytosis pathway. These results suggest that interaction between Epsin and the gp41 core, which may be present in the target cell membrane, is probably essential for endocytosis of HIV-1, an alternative pathway of HIV-1 entry into the target cell.

The interaction of the viral envelope glycoprotein surface subunit gp120 with the primary receptor CD4 (1) and a chemokine coreceptor (CXCR4 or CCR5) (2) is the first step of human immunodeficiency virus, type 1 (HIV-1),3 entry into the target cell. Then the fusion peptide at the gp41 N terminus inserts into the target cell membrane. Subsequently, the N- and C-terminal heptad repeat (NHR and CHR, respectively) regions associate to form a six-helix bundle (6-HB; also known as trimer-of-heterodimers or trimer-of-hairpins), which represents the gp41 core structure (3–5). Formation of the 6-HB is believed to bring the viral and target cell membranes into close proximity to facilitate their merging (3, 6, 7).

We have previously demonstrated that HIV-1 gp41 binds to some proteins with molecular masses of 45 and 62 kDa (P45 and P62, respectively) on the surface of T and B lymphocytes and monocytes via its N- or C-terminal domain (8, 9). Others have reported that HIV-1 gp41 interacts with a 60-kDa heat-shock protein-like molecule (10) and human leukocyte elastase (11). Alfsen et al. (12) have shown that HIV-1 binds to the epithelial glycosphingolipid galactosylceramide, which is an alternative receptor for HIV-1, via a site involving the conserved ELDKWA epitope in gp41. It has been reported that lipid rafts, consisting of sphingolipids and cholesterol, are being utilized by HIV-1 to enter the target cells (13). Hovanessian et al. (14) have shown that gp41 binds to a major integral protein in the membrane of caveolae, caveolin-1, and forms a complex in the HIV-1-infected cells. We demonstrated that the HIV-1 gp41 core interacts with a hydrophobic motif ΦXXXXΦXXΦ (where X is any amino acid and Φ is W, Y, or F) in the scaffolding domain of caveolin-1 (15). Wang and co-workers (16–18) have reported that gp41 and the peptides derived from gp41, e.g. N36, T20, and T21, attract and activate human phagocytes by using G-protein-coupled formyl peptide receptors. We also identified a gp41 core-binding motif HXXNPF by screening the phage display peptide library (19) and found that the peptides containing the HXXNPF motif could inhibit HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein-mediated syncytium formation (20). These data suggest that HXXNPF motif-containing molecules may specifically bind to the HIV-1 gp41 core to block HIV-1 entry.

In this study, we sought to identify the cellular gp41 core-binding proteins. Mutational analysis demonstrated that the most conservative residues in the gp41-binding motif HXXNPF were Asn, Pro, and Phe. By searching the protein data base, we found that Epsin contains the NPF motifs in the C-terminal domain. Epsin plays an important role in the clathrin-mediated endocytosis (21). Epsin N-terminal homology (ENTH) domain binds to the cell membrane through the lipid PIP2 and phosphatidylinositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate to induce positive membrane curvature and tubulation of plasma membrane. Its central region contains eight copies of DPW motifs that are necessary for binding of Epsin to the adaptor protein complex 2 (AP-2). A clathrin-binding site, which is adjacent to the DPW motifs in Epsin, can simultaneously interact with two clathrin terminal domains (22). The C-terminal region of Epsin consists of three NPF motifs responsible for association of Epsin with the Eps15 homology (EH) domain of Eps15, intersectin, and POB1 during the process of endocytosis (23).

We constructed a recombinant protein, Epsin-1-(470–499), that spans the amino acid residues 470–499 of Epsin and contains two NPF motifs. Epsin-1-(470–499) bound significantly to the gp41 expressed in mammalian cells and interacted with the gp41 core. Endocytosis of HIV-1 particles into T cells could be blocked by the peptide containing the Epsin-1-(470–499) sequence. These results suggest that via the unique NPF motifs, Epsin may interact with the gp41 core of HIV-1, perhaps in the target cell membrane. This interaction may involve the pathogenesis of HIV-1 infection as well as an alternative pathway, i.e. endocytosis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Lines and Transient Transfection—293T cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with antibiotics and 10% fetal bovine serum. Transfection was performed using Vigofect reagent (Vigorous Biotechnology, Inc., Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Cells were plated in a 6-well tissue culture plate 24 h prior to transfection. Cells at 50–70% confluency were transfected with 5 μg of plasmid DNA. Cells were collected 48 h after transfection. SupT1 T cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin.

Construction of Mutants of L7.8-g3p*—We used a standard site-directed mutagenesis procedure to introduce mutations into the sequence of L7.8-g3p*, a fragment of the gene 3 protein (g3p) of the phage clone L7.8 containing the gp41 core-binding motif. Expression plasmids were constructed by inserting the DNA fragments encoding H19A, N22A, P23A, and F24A mutants of L7.8-g3p*, respectively, into an expression vector of the pET-28b series. After ligation and electroporation, recombinant clones were identified by PCR. The inserted DNA fragments were sequenced to exclude any undesirable mutations. The same procedures for expression and purification of the wild-type L7.8-g3p* (20) were used for the L7.8-g3p* mutants.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Assay—The kinetics of the binding affinity of the mutants of L7.8-g3p* (H19A, N22A, P23A, and F24A) to N36(L8)C34 were determined by SPR using the Biacore 2000 system (GE Healthcare) at 25 °C. N36(L8)C34 (10 μg/ml) was immobilized onto the CM5 sensor chip according to the amine coupling protocol, and the unreacted sites were blocked with 1 m Tris-HCl (pH 8.5). The association reaction was initiated by injecting the peptide (0.5 μm) at a flow rate of 5 μl/min. The dissociation reaction was done by washing with PBS. Wild-type L7.8-g3p* was used as a control. At the end of each cycle, the sensor chip surface was regenerated with 0.1 m glycine-HCl (pH 2.5) for 30 s.

Expression and Purification of GST-Eps15-EH2 Domain and GST-Epsin-1-(470–499) Fusion Proteins—For expression of GST-Eps15-EH2 domain and GST-Epsin-1-(470–499) fusion proteins, the gene fragments encoding the Eps15-EH2 domain and Epsin-1-(470–499) were amplified with PCR from the genome of the U937 cell with the following primers: Eps15-EH2 domain forward, 5′CGGAATTCGATTCGGATAAGGCCAAATATGATGC3′, and reverse, 5′CCGCTCGAGTCATTTTTCTCTTAGATGGTGG3′; Epsin-1-(470–499) forward, 5′ CGCGGATCCCCTGGAGCTAAGGCTTCTAACCCTTTTCTTCCAGGAGGAGGACCAGCTACTGGA3′, and reverse, 5′CCGCTCGAGTGGAGGAGCTGGCTGGAATGGGTTAGTAACGGAAGGTCCAGTAGCTGGT3′. The fragments were cloned into the expression plasmid pGEX-6P via its EcoRI and XhoI restriction sites, and the proteins were overproduced in Escherichia coli strain Rosetta. The cells were lysed with PBS (pH 7.2) using sonication. After centrifugation, the supernatants containing the fusion protein were collected. The GST-Eps15-EH2 domain and GST-Epsin-1-(470–499) fusion proteins were then purified by glutathione-Sepharose 4B affinity columns and analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

Pulldown Assay—The in vitro pulldown assay was carried out as described previously (23). The pellet of the 293T cells expressing the EGFP-tagged Epsin-1-(470–499) was solubilized in 0.2 ml of ice-cold lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100, 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm Na3VO4, 1 mm EGTA, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 5 mg/ml leupeptin, 5 mg/ml pepstatin) at 4 °C for 30 min. The supernatants were collected after centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. GST-Eps15-EH2 domain conjugated glutathione-Sepharose beads were incubated with the supernatants on ice for 2 h. GST-conjugated glutathione-Sepharose beads were used as a control. The beads were washed five times with lysis buffer. The bound protein was detected by Western blot with rabbit polyclonal anti-EGFP antibody. Similar procedures were used for pulling down the complex of GST-N36(L8)C34 with EGFP-Epsin-1-(470–499) expressed in the transfected 293T cells. EGFP was used as a control.

For pulling down the complex of GST-Epsin-1-(470–499) with human IgG Fc-tagged recombinant soluble gp41 (rsgp41) expressed in the transfected 293T cells, 293T cells lysates were prepared by incubating 293T cells in 0.2 ml of lysis buffer at 4 °C for 30 min. After centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 30 min at 4 °C, the supernatants containing human IgG Fc-tagged rsgp41 (rsgp41-Fc) were collected and incubated with GST and GST-Epsin-1-(470–499), respectively. Protein G-Sepharose-beads (10 μl) were added, followed by incubation on ice for 2 h with shaking. The beads were washed with TBS buffer (1% Triton X-100, 50 mm Tris-HCl, 150 mm NaCl (pH 7.4)) five times. The bound gp41 was eluted by heating with SDS-PAGE sample buffer and detected by Western blot with the polyclonal anti-EGFP antibody.

Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)—To test whether human IgG Fc-tagged rsgp41 (rsgp41-Fc) expressed in the cytoplasm of 293T cells could form core structures, 100 μl of rsgp41-Fc-expressing 293T cell lysates at 4-fold serial dilutions in 0.1 m NaHCO3 were coated in the wells of microplates. The lysates of wild-type 293T cells were used as a control. After blocking and washing, 50 μl of the mAb NC-1 (10 μg/ml) were added and incubated at room temperature for 2 h, followed by addition of peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG and substrate o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride, sequentially. Absorbance at 450 nm (A450) was measured.

Synthesis of the Peptide Containing Epsin-1-(470–499) Sequence—The peptide containing the Epsin-1-(470–499) sequence, designated SJ-3136 (Table 1), was synthesized by a standard solid-phase Fmoc (N-(9-fluorenyl)methoxycarbonyl) method and purified to homogeneity by high performance liquid chromatography. The identity of the purified peptides was confirmed by laser desorption mass spectrometry (PerSeptive Biosystems).

TABLE 1.

Amino acid sequences of Epsin-1(470–499)/peptide SJ-3136 and Eps15-EH2

| Epsin-1-(470-499) and peptide SJ-3136a |

| PGAKASNPFLPGGGPATGPSVTNPFQPAPP |

| Eps15-EH2 (residues 128-216) |

| DSDKAKYDAIFDSLSPVNGFLSGDKVKPVLLNSKLPVDILGRVWELSDIDHDGMLDRDEFAVAMFLVYCALEKEPVPMSLPPALVPPSKRK |

The NPF motif is in boldface and underlined.

Competition ELISA—Mouse anti-SJ-3136 antisera were obtained from BALB/c mice that were immunized with the peptide SJ-3136, which was conjugated with bovine serum albumin three times with Freund's adjuvant. To test whether SJ-3136 could compete with NC-1 in binding to the gp41 core, the wells of a microplate (Costar, High Binding) were coated with 100 μl of rabbit IgG (2 μg/ml) against the gp41 6-HB core formed by the peptides N36 and C34 (7). After blocking with blocking buffer, 100 μl of N36(L8)C34 at 5 μg/ml in PBS were added into each well and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. After extensive washes, 25 μl of SJ-3136 at graded concentrations were added and incubated at 37 °C for 60 min, followed by addition of 25 μl of NC-1 (0.1 μg/ml). After incubation at 37 °C for 30 min, the amount of bound NC-1 was detected by adding biotin-goat anti-mouse IgG, streptavidin-labeled horseradish peroxidase, and 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine substrate solution, sequentially. Absorbance at 450 nm was recorded.

Preparation of HIV-1 Virions Labeled with GFP—293T cells were cotransfected with HIV-1 pNL4-3 proviral DNA (24 μg) and pEGFP-Vpr (24 μg) using Lipofectamine (60 μl, Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. After overnight culture at 37 °C, the medium was replaced completely with fresh culture medium. Two days after transfection, supernatants of cells were collected and centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 15 min. The supernatants were transferred to sterile ultracentrifuge tubes and then centrifuged in an SW28 rotor at 20,000 rpm at 4°C for 2 h to sediment the viral particles. The virions in the pellet were resuspended in RPMI 1640 complete medium (0.5 ml) and stored in aliquots at –80 °C until use.

Flow Cytometric Analysis of HIV-1 Entry into Target Cells via Endocytosis and Fusion—HIV-1 entry into target cells through endocytosis and fusion was determined by flow cytometry as described previously (24). Briefly, human SupT1 T cells (2 × 105) were suspended in fresh medium in the absence or presence of inhibitors, i.e. AMD3100 (40 μg/ml), chlorpromazine (20 μg/ml), and SJ-3136 (1 mg/ml) and combinations thereof, at 37 °C for 30 min, followed by addition of GFP-labeled virions (200 ng of p24 Gag). After incubation at 37 °C for 4 h, the cells were washed twice with PBS and then treated with a trypsin/EDTA solution (1×; Sigma) for 4 min at 37 °C to remove surface-bound virions. Cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde/PBS solution, and cellular GFP virion uptake was measured by flow cytometry (Canto, BD Biosciences).

RESULTS

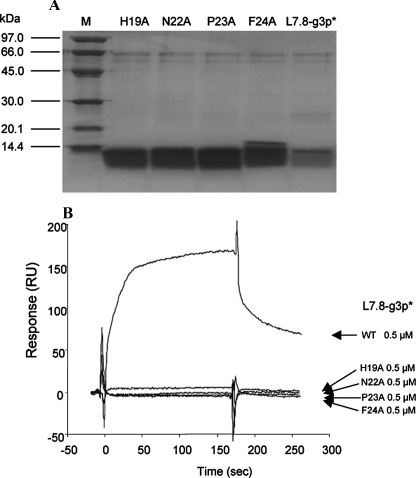

Mutations of the Key Residues in the gp41 Core-binding Motif of the L7.8-g3p* Mutants Resulted in Loss of gp41 Core Binding Activity—To determine which key residues of the HXXNPF motif of L7.8-g3p* are responsible for binding to the gp41 core, His-19, Asn-22, Pro-23, and Phe-24, respectively, were substituted with alanine by site-directed mutagenesis. Four mutants of L7.8-g3p* (named H19A, N22A, P23A, and F24A) were constructed. E. coli bearing the expression vectors was grown to log-phase, and fusion protein expression was induced by adding isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside. The His-tagged wild-type L7.8-g3p* and four L7.8-g3p* mutants purified by metal affinity chromatography from the cell lysates had a molecular mass of about 10 kDa (Fig. 1A). The respective binding affinities of the mutants to N36(L8)C34 were compared with that of the wild-type L7.8-g3p* by SPR. As shown in Fig. 1B, the mutant H19A showed significantly reduced binding affinity, and the mutants N22A, P23A, and F24A completely lost their ability to bind to N36(L8)C34. These results demonstrate that the residues Asn, Pro, and Phe in the HXXNPF motif were definitely essential for interaction with the gp41 core, suggesting that the protein containing the NPF motif may specifically bind to the HIV-1 gp41 core.

FIGURE 1.

Purification and characterization of the L7.8-g3p* mutants. A, SDS-PAGE image of L7.8-g3p* and its mutants, H19A, N22A, P23A, and F24A, purified with metal affinity chromatography. Lane M, protein standard marker. B, binding affinities of WT-L7.8-g3p* and four mutants (0.5 μm) to N36(L8)C34 measured by SPR using the BIAcore 2000 system.

Interaction of Epsin-1-(470–499) with Eps15-EH2—We learned from a search of the protein data base that the NPF motif is present in many proteins, e.g. Epsin (25, 26), Ap180 (27), Numb (28), and Hrb (29). No sequence homology was found in these proteins except for the presence of one or more copies of the NPF motif. The NPF motif was demonstrated to be indispensable in vivo for the binding of the identified proteins to the EH domains of Eps15 (30). Eps15 is important for an endocytic entry pathway utilized by HIV-1. Expression of a dominant-negative mutant of Eps15 leads to reduction of HIV entry in HeLa cells by about 95%, confirming that the endocytosis pathway is also necessary for causing infection (21). Epsin is the Eps15-interacting protein and promotes the assembly of clathrin. Therefore, we speculated that the gp41 core might be involved in the clathrin-dependent endocytosis through interaction with the NPF motif of Epsin.

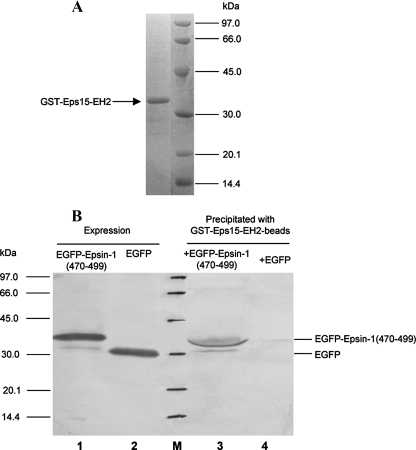

It was reported that the fragment of Epsin-(433–551), which contains three copies of NPF motifs, bound to the EH domain of Eps15 directly (23). In this study, Epsin-1-(470–499) containing two copies of NPF motif (Table 1) was amplified by PCR. The EH2 domain of Eps15 was constructed as a GST fusion protein (GST-Eps15-EH2) (Table 1) and purified with the glutathione-Sepharose 4B affinity column. As shown in Fig. 2A, the purified GST-Eps15-EH2 migrated through the SDS-PAGE revealing a band with an expected molecular size of 37 kDa.

FIGURE 2.

A, SDS-PAGE image of GST-Eps15-EH2 domain purified with glutathione-Sepharose affinity chromatography. The molecular mass of GST-Eps15-EH2 was about 37 kDa. B, interaction of the GST-Eps15-EH2 domain with EGFP-Epsin-1-(470–499) expressed in 293T cells. EGFP-Epsin-1-(470–499) (lane 1) or EGFP (lane 2) expressed in the transfected 293T cells was probed with anti-EGFP antibodies. Glutathione-Sepharose bead-conjugated GST-Eps15-EH2 domain was incubated with the lysates of 293T cells expressing EGFP-Epsin-1-(470–499) (lane 3) or EGFP (lane 4), respectively. The bound proteins were eluted and probed with the polyclonal antibodies against EGFP. Lane M, protein standard marker.

To define whether GST-Epsin-1-(470–499) with two copies of the NPF motif still retains binding activity to Eps15, we transfected 293T cells with the plasmid of pcDNA3.0-EGFP-Epsin-1-(470–499) to express the EGFP-tagged Epsin-1-(470–499). The 293T cells transfected with an empty EGFP vector was used as a control. GST-Eps15-EH2 coupled to glutathione-Sepharose beads was added to the respective cell lysates. If GST-Eps15-EH2 bound to EGFP-Epsin-1-(470–499) in the cell lysates, these two proteins then coprecipitated with glutathione-Sepharose beads. EGFP fusion proteins in the eluates could be detected by anti-EGFP antibodies in Western blotting. As shown in Fig. 2B, EGFP-Epsin-1-(470–499) (lane 1) and EGFP (lane 2) showed bands with respective anticipated molecular sizes. EGFP-Epsin-1-(470–499) expressed in the 293T cells bound strongly to GST-Eps15-EH2 (Fig. 2B, lane 3), whereas the control EGFP did not interact with the GST-Eps15-EH2 (lane 4). These results confirm that Epsin-1-(470–499) still retains its binding ability to Eps15-EH2. The NPF motifs present in GST-Epsin-1-(470–499) are apparently responsible for the interaction of Epsin with Eps15. Therefore, Epsin-1-(470–499) was used in the following experiments to test for any interaction with the gp41 core.

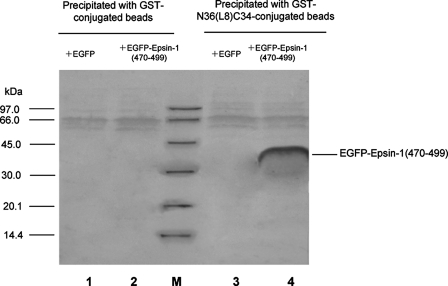

Interaction of EGFP-Epsin-1-(470–499) with the gp41 Core Modeled by N36(L8)C34—A pulldown assay with the polypeptide N36(L8) C34 as a model of the gp41 core was used to detect the binding ability of Epsin-1-(470–499) to the core of gp41. The lysates of 293T cells expressing EGFP-Epsin-1-(470–499) were incubated with GST and GST-N36(L8)C34, respectively, conjugated to glutathione-Sepharose beads. The pulldown proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and probed by polyclonal antibodies against EGFP. As shown in Fig. 3, GST beads pulled down no protein (lanes 1 and 2) from the 293T cell lysates. GST-N36(L8)C34-beads could not capture EGFP (Fig. 3, lane 3) but effectively precipitated EGFP-Epsin-1-(470–499) (lane 4). These results demonstrate that Epsin-1-(470–499) can specifically interact with the core of gp41.

FIGURE 3.

Interaction of EGFP-Epsin-1-(470–499) with the gp41 core formed by N36(L8)C34. Glutathione-Sepharose bead-conjugated GST was incubated with the lysates of 293T cells expressing EGFP (lane 1) or EGFP-Epsin-1-(470–499) (lane 2), whereas the glutathione-Sepharose bead-conjugated GST-N36(L8)C34 was incubated with the lysates of 293T cells expressing EGFP (lane 3) or EGFP-Epsin-1-(470–499) (lane 4), respectively. The bound proteins were eluted and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with the anti-EGFP antibody. Lane M, protein standard marker.

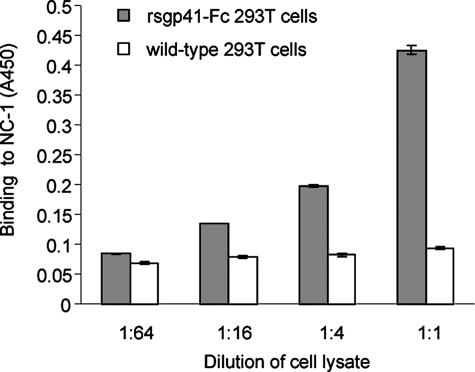

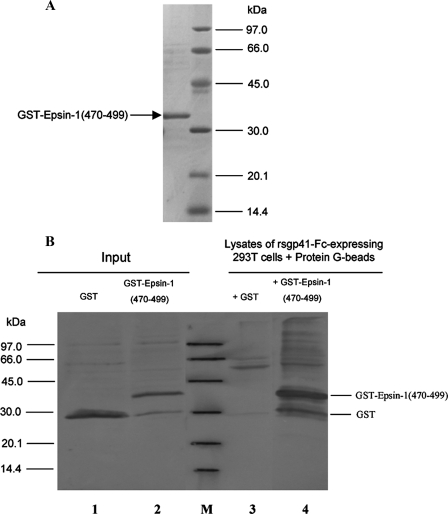

Interaction of GST-Epsin-1-(470–499) with Recombinant Soluble gp41 (rsgp41)—It has been reported that the purified rsgp41 has a tendency to form a core-like structure, i.e. its NHR and CHR regions may associate to form a 6-HB (31). The plasmid of pcDNA3.0-pIg-rsgp41 was transfected into the 293T cells to express human IgG Fc-tagged rsgp41 (rsgp41-Fc) fusion protein in cytoplasm. NC-1, a mAb that is specific for the gp41 core conformation (7), could react with the lysates of rsgp41-Fc-expressing 293T cells in ELISA, whereas the control wild-type 293T cells showed no binding activity (Fig. 4), suggesting that rsgp41-Fc contains the gp41 core structure. Therefore, it was of interest to investigate whether the rsgp41 containing the core structure could also bind to Epsin-1-(470–499). To determine the interaction between Epsin-1-(470–499) and rsgp41, Epsin-1-(470–499) was constructed as a GST fusion protein, GST-Epsin-1-(470–499). This fusion protein was expressed in E. coli and purified using glutathione-Sepharose 4B affinity column. The purified GST-Epsin-1-(470–499) migrated through the SDS-PAGE at an apparent size of 31 kDa (Fig. 5A). GST-Epsin-1-(470–499) and GST, respectively, were added to the rsgp41-Fc-expressing 293T cell lysates. If GST-Epsin-1-(470–499) bound to the endogenous rsgp41-Fc in the cell lysates, these two proteins were then coprecipitated with protein G-conjugated beads. GST fusion proteins in the eluates could be detected by anti-GST antibodies in Western blotting. For comparison, an identical amount of GST was used as a control. As shown in Fig. 5B, the input GST-Epsin-1-(470–499) (lane 2) exhibited two bands, the lower one corresponds to GST and the upper one to GST-Epsin-1-(470–499), whereas the input GST (lane 1) showed only one band. GST-Epsin-1-(470–499) was well precipitated because of its binding to rsgp41-Fc (Fig. 5B, lane 4), whereas GST could not be coprecipitated by rsgp41-Fc (lane 3). These results suggest that GST-Epsin-1-(470–499) can bind to the rsgp41-Fc containing the core structure.

FIGURE 4.

Detection of the core structure formed by rsgp41 with mAb NC-1. Binding of NC-1 to rsgp41-Fc expressed in the 293T cells was measured by ELISA. Wild-type 293T cells were used as the control.

FIGURE 5.

A, SDS-PAGE image of GST-Epsin-1-(470–499) purified by glutathione-Sepharose affinity chromatography. The molecular mass of GST-Epsin-1-(470–499) was about 31 kDa. B, interaction of GST-Epsin-1-(470–499) with endogenous rsgp41 expressed in 293T cells. The purified protein of GST (lane 1) and GST-Epsin-1-(470–499) (lane 2) in the input samples was probed with anti-GST antibodies. The lysates of rsgp41-Fc-expressing 293T cells were incubated with GST (lane 3) or GST-Epsin-1-(470–499) (lane 4) and precipitated with protein G beads. The bound proteins were eluted and probed with the polyclonal antibodies against GST. Lane M, protein standard marker.

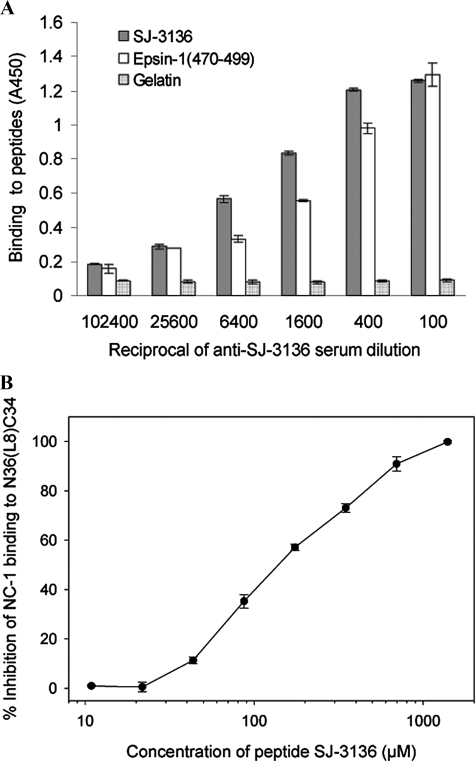

Blockage of mAb NC-1 Binding to the gp41 6-HB Core by a Synthetic Peptide Containing the Epsin-1-(470–499) Sequence—To confirm the interaction between Epsin-1-(470–499) and the HIV-1 gp41 core during endocytosis, a peptide containing the Epsin-1-(470–499) sequence (designated SJ-3136) was synthesized. Mouse antisera directed against the peptide SJ-3136 reacted equally well with both SJ-3136 and Epsin-1-(470–499) (Fig. 6A). In the competition ELISA, peptide SJ-3136 blocked the binding of mAb NC-1 to N36(L8)C34 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6B). These data further confirm that Epsin-1-(470–499) specifically binds to the gp41 core.

FIGURE 6.

A, binding of anti-SJ-3136 antibodies in mouse serum to synthetic peptide SJ-3136 and Epsin-1-(470–499). Gelatin was used as the negative control. B, inhibition of peptide SJ-3136 on NC-1 binding to N36(L8)C34. The samples were tested in triplicate, and the data were presented as means ± S.D.

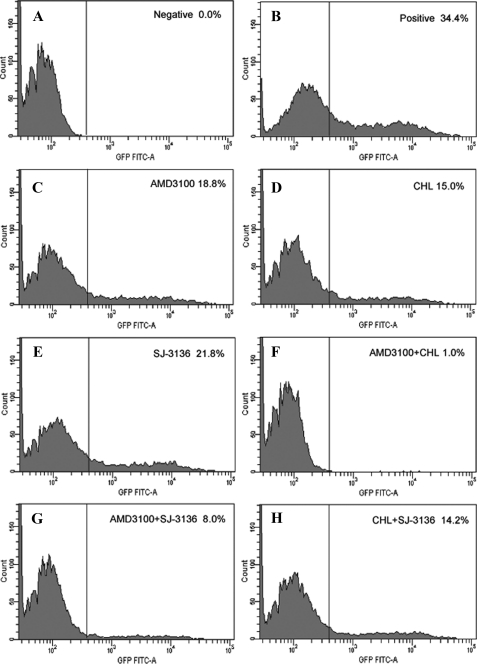

Inhibitory Activity of the Peptide SJ-3136 on Endocytosis of HIV-1 Particles—To further examine whether SJ-3136 could block the entry of HIV-1 virus via the endocytosis pathway, we constructed GFP-vpr-labeled X4-tropic HIV-1 virions and determined the inhibitory activity of SJ-3136 on endocytosis of HIV-1 virions. AMD3100, a fusion inhibitor targeting CXCR4, and chlorpromazine, a drug disrupting clathrin-mediated endocytosis, were used as controls. As shown in Fig. 7 and Table 2, after 4 h of incubation with a viral input of 200 ng of p24, AMD3100, chlorpromazine, and SJ-3136, when tested individually, effectively inhibited HIV-1 entry into SupT1 T cells (45.19, 56.27, and 36.44%, respectively). The inhibitory activity of the AMD3100/chlorpromazine combination on virus entry (97.08%) was significantly higher than that of AMD3100 or chlorpromazine alone. Combination of SJ-3136 and AMD3100 exhibited significantly higher inhibition (78.68%) of HIV-1 entry than SJ-3136 or AMD3100 alone. However, combination of SJ-3136 and chlorpromazine exhibited no significant increase in inhibition of virus entry (58.6%). These results suggest that SJ-3136, like chlorpromazine, inhibits HIV-1 virion entry via the endocytosis pathway.

FIGURE 7.

Inhibitory activity of peptide SJ-3136, AMD3100, chlorpromazine, and respective combinations on HIV-1 entry into SupT1 T cells. SupT1 T cells were incubated with PBS as the negative control (A), with HIV-1 particles as the positive control (B), and with HIV-1 particles in the presence of AMD3100 (C), chlorpromazine (D), peptide SJ-3136 (E), AMD3100 + chlorpromazine (F), AMD3100 + SJ-3136 (G), and chlorpromazine + SJ-3136 (H), respectively. The percent of cells containing GFP-labeled HIV-1 particles was indicated in each panel.

TABLE 2.

Inhibitory activity of the peptide SJ-3136, AMD3100, chlorpromazine, and their respective combinations on HIV-1 entry into target cells

| Inhibitorsa | Virus entry | Inhibition of virus entry | Inhibition of |

|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | ||

| AMD3100 | 18.8 | 45.19 | Fusion |

| Chlorpromazine | 15.0 | 56.27 | Endocytosis |

| SJ-3136 | 21.8 | 36.44 | Endocytosis |

| AMD3100 + SJ-3136 | 8.0 | 76.68 | Fusion + endocytosis |

| Chl + SJ-3136 | 14.2 | 58.60 | Endocytosis |

| AMD3100 + Chl | 1.0 | 97.08 | Fusion + endocytosis |

| Negative control | 0.0 | ||

| Positive control | 34.4 |

The concentrations of the compounds used are as follows: AMD3100 = 40 μg/ml; chlorpromazine (Chl) = 20 μg/ml; SJ-3136 = 1 mg/ml. Positive control is cells + virus; negative control is cells + PBS. The percent inhibition of virus entry into target cells via fusion (e.g. AMD3100) or endocytosis (e.g. chlorpromazine) was determined as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

DISCUSSION

HIV-1 uses fusion and endocytosis as the main and alternative pathways, respectively, to enter the target cells (24). In the case of fusion, the viral and target cell membranes are allegedly brought into close proximity by the gp41 core to facilitate merging of the membranes (3). Some virions may have lost their fusion ability, possibly resulting from the interaction between gp120 on virions and soluble CD4 molecules that are released from CD4+ cells, triggering the gp41 core formation (31, 32). Furthermore, the degraded fragments from HIV-1 gp41 may interact with the viral gp41 NHR and CHR regions to form heterologous 6-HBs, blocking further progress of membrane fusion. Although lacking fusion ability, these virions may still be capable of entering the target cells via endocytosis.

It has been shown that two principal types of endocytosis mediated by caveolae/raft and clathrin are used by different viruses (33, 34). Manes et al. (16) have demonstrated that lateral assembly mediated by the membrane raft microdomain is required for HIV-1 entry. Our previous studies suggest that interaction of the HIV-1 gp41 core with the scaffolding domain of caveolin-1 may be involved in the endocytosis of HIV-1 (20). Eps15 plays an important role in clathrin-mediated endocytic entry pathway utilized by HIV-1 because a dominant-negative mutant of Eps15 results in about 95% reduction of HIV entry into HeLa cells (21). The EH domain of Eps15 interacts with the C-terminal region of Epsin during the process of endocytosis (23).

We previously identified an HIV-1 gp41 core-binding motif, HXXNPF, which also contains the NPF sequence (19). We thus hypothesized that the NPF sequence may be the key residues in the HIV-1 gp41 core-binding proteins. In this study, we confirmed that Asn, Pro, and Phe were indeed the key residues, because mutations of these residues in the gp41 core-binding motif of L7.8-g3p* resulted in loss of gp41 core-binding activity (Fig. 1).

Because the C-terminal region of Epsin contains three NPF motifs and Epsin is an essential accessory factor of clathrin-mediated endocytosis, which controls the internalization of extracellular macromolecules and cell surface receptors (35), we envisaged that Epsin might interact via its NPF motif with the gp41 core to mediate the HIV-1 endocytosis. To prove this hypothesis, we constructed a fusion protein, GST-Epsin-1-(470–499), containing two copies of NPF motifs, and tested its binding activity to Eps15. The results indicate that Epsin-1-(470–499) can interact with Eps15-EH2 (Fig. 2B), confirming that Epsin-1-(470–499) retains the binding ability of Epsin to Eps15. We further demonstrated that Epsin-1-(470–499) could bind very well to the gp41 core formed by the polypeptide N36(L8)C34 (Fig. 3). It was also capable of capturing gp41 expressed in the cytoplasm (Fig. 5B), and which spontaneously formed 6-HBs (Fig. 4).

To determine the potential role of Epsin-1-(470–499) in HIV-1 entry mediated by the gp41 core, a peptide containing the Epsin-1-(470–499) sequence (SJ-3136) was synthesized and tested for its inhibitory activity on HIV-1 entry into the target cells. Schaeffer et al. (24) have employed flow cytometry to analyze the entry of GFP-Vpr-labeled HIV-1 particles into SupT1 cells and used AMD3100, a CXCR4-specific fusion inhibitor, and chlorpromazine, an endocytosis inhibitor, to determine the pathway of viral entry. Using the same approaches, we tested the potential inhibitory activity of SJ-3136 on HIV-1 entry into target cells via fusion or endocytosis. As shown in Fig. 7 and Table 2, the combination of AMD3100 and chlorpromazine resulted in significantly higher inhibitory activity on HIV-1 entry than that of AMD3100 and chlorpromazine tested separately. This confirms that these two compounds have different mechanisms of action and that their combination has synergistic effects on the inhibition of HIV-1 entry. Similarly, the combination of SJ-3136 with AMD3100 exhibited more potent inhibition of HIV-1 entry than that of SJ-3136 or AMD3100 alone. These results suggest that, like chlorpromazine, peptide SJ-3136 inhibits HIV-1 entry via the endocytosis pathway.

Based on these findings, we propose that the HIV-1 gp41 core may interact with the NPF motifs in Epsin to facilitate endocytosis of HIV-1 particles. This interaction is perhaps triggered with the assistance of a number of cellular proteins, such as clathrin, PIP2, AP-2, and dynamin. This hypothesis is in agreement with the observation that HIV-1 virions could traverse between cells by a clathrin-dependent endocytic process (36). In the cytosolic domain of gp41 there are two highly conserved tyrosine-based motifs (712YSPL and 768YHRL) and a conserved  motif, which can specifically bind to the clathrin-associated protein AP-2. This results in the internalization of the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein (37, 38) suggesting that the cytosolic domain of gp41 may also play an important role in the endocytosis of HIV-1.

motif, which can specifically bind to the clathrin-associated protein AP-2. This results in the internalization of the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein (37, 38) suggesting that the cytosolic domain of gp41 may also play an important role in the endocytosis of HIV-1.

One may question where the HIV-1 gp41 extracellular core domain interacts with Epsin, which is normally localized inside cell. We speculate that the gp41 core may bind to Epsin in the target cell membrane. Previous studies indicated that the gp41 6-HB core could bind to the lipid membranes (39), and its NHR domain could further interact with the target cell membrane to facilitate fusion pore formation (40). Most recently, Benferhat et al. (41) reported that the caveolin-1 binding domain in the HIV-1 gp41, which partially overlaps with the CHR region, could penetrate the cell membrane to bind caveolin-1 inside the cell. Epsin can also bind to the plasma membrane through the interaction between the ENTH domain of Epsin and the lipid PIP2 to initiate the membrane curvature and coat-pit formation and promote the assembly of clathrin. Mutations in the ENTH domain result in abolishment of Epsin binding to the lipid membrane (42). It was reported that Epsin could interact with the epithelial sodium channel expressed on the cell surface and mediate the clathrin-based endocytosis of the epithelial sodium channel (43).

This study presents the initial evidence for a direct interaction between the HIV-1 gp41 core and the NPF motif of Epsin, probably in the target cell membrane, which may facilitate the endocytosis of HIV-1 particles. The potential site(s) where gp41 core interacts with Epsin and the gp41 core-binding motif(s) in other proteins, such as AP180, Numb, and Hrb, also merit further investigation to provide information for understanding the endocytosis of HIV-1 virions and the pathogenesis of HIV-1 infection, as well as for rational design of novel HIV-1 entry inhibitors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ping Cui for technical assistance in developing the assay for endocytosis of HIV-1 particles and Veronica L. Kuhlemann at the Viral Immunology Laboratory, New York Blood Center, for editorial assistance. HIV-1 pNL4-3 proviral DNA and pEGFP-Vpr were obtained from the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, National Institutes of Health, and were contributed by Drs. Malcolm Martin and Warner C. Greene, respectively.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant AI46221 (to S. J.). This work was also supported by the Emphases Project of the Natural Science Foundation of China NSFC-30530680 and 2007CB914402 (to Y. H. C.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: HIV-1, human immunodeficiency virus, type 1; 6-HB, six-helix bundle; CHR, C-terminal heptad repeat; NHR, N-terminal heptad repeat; EH, Eps15 homology; ENTH, Epsin N-terminal homology; g3p, gene 3 protein; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-biphosphate; SPR, surface plasmon resonance; mAb, monoclonal antibody; GFP, green fluorescent protein; EGFP, enhanced GFP; GST, glutathione S-transferase; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; AP-2, adaptor protein complex 2.

References

- 1.Sattentau, Q. J., and Moore, J. P. (1993) Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 342 59–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger, E. A., Murphy, P. M., and Farber, J. M. (1999) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 17 657–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu, M., Blacklow, S. C., and Kim, P. S. (1995) Nat. Struct. Biol. 2 1075–1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan, D. C., Fass, D., Berger, J. M., and Kim, P. S. (1997) Cell 89 263–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weissenhorn, W., Dessen, A., Harrison, S. C., Skehel, J. J., and Wiley, D. C. (1997) Nature 387 426–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan, D. C., and Kim, P. S. (1998) Cell 93 681–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang, S., Lin, K., and Lu, M. (1998) J. Virol. 72 10213–10217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, Y. H., Ebenbichler, C., Vornhagen, R., Schulz, T. F., Steindl, F., Bock, G., Katinger, H., and Dierich, M. P. (1992) AIDS 6 533–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, Y. H., Xiao, Y., Wu, W., Yang, J., Sui, S., and Dierich, M. P. (1999) AIDS 13 1021–1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Speth, C., Prohaszka, Z., Mair, M., Stockl, G., Zhu, X., Jobstl, B., Fust, G., and Dierich, M. P. (1999) Mol. Immunol. 36 619–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bristow, C. L., Mercatante, D. R., and Kole, R. (2003) Blood 102 4479–4486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alfsen, A., Iniguez, P., Bouguyon, E., and Bomsel, M. (2001) J. Immunol. 166 6257–6265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dimitrov, A. S., Rawat, S. S., Jiang, S., and Blumenthal, R. (2003) Biochemistry 42 14150–14158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hovanessian, A. G., Briand, J. P., Said, E. A., Svab, J., Ferris, S., Dali, H., Muller, S., Desgranges, C., and Krust, B. (2004) Immunity 21 617–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang, J. H., Lu, L., Lu, H., Chen, X., Jiang, S., and Chen, Y. H. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 6143–6152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manes, S., del Real, G., Lacalle, R. A., Lucas, P., Gomez-Mouton, C., Sanchez-Palomino, S., Delgado, R., Alcami, J., Mira, E., and Martinez, A. (2000) EMBO Rep. 1 190–196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Su, S. B., Gao, J., Gong, W., Dunlop, N. M., Murphy, P. M., Oppenheim, J. J., and Wang, J. M. (1999) J. Immunol. 162 5924–5930 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Su, S. B., Gong, W. H., Gao, J. L., Shen, W. P., Grimm, M. C., Deng, X., Murphy, P. M., Oppenheim, J. J., and Wang, J. M. (1999) Blood 93 3885–3892 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang, J. H., Liu, Z. Q., Liu, S., Jiang, S., and Chen, Y. H. (2006) FEBS Lett. 580 4807–4814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang, J. H., Yang, H. W., Liu, S., Li, J., Jiang, S., and Chen, Y. H. (2007) Biochem. J. 403 565–567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daecke, J., Fackler, O. T., Dittmar, M. T., and Krausslich, H. G. (2005) J. Virol. 79 1581–1594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalthoff, C., Alves, J., Urbanke, C., Knorr, R., and Ungewickell, E. J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 8209–8216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakashima, S., Morinaka, K., Koyama, S., Ikeda, M., Kishida, M., Okawa, K., Iwamatsu, A., Kishida, S., and Kikuchi, A. (1999) EMBO J. 18 3629–3642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schaeffer, E., Soros, V. B., and Greene, W. C. (2004) J. Virol. 78 1375–1383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamabhai, M., Hoffman, N. G., Hardison, N. L., McPherson, P. S., Castagnoli, L., Cesareni, G., and Kay, B. K. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 31401–31407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen, H., Fre, S., Slepnev, V. I., Capua, M. R., Takei, K., Butler, M. H., Di Fiore, P. P., and De Camilli, P. (1998) Nature 394 793–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wendland, B., and Emr, S. D. (1998) J. Cell Biol. 141 71–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salcini, A. E., Confalonieri, S., Doria, M., Santolini, E., Tassi, E., Minenkova, O., Cesareni, G., Pelicci, P. G., and Di Fiore, P. P. (1997) Genes Dev. 11 2239–2249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doria, M., Salcini, A. E., Colombo, E., Parslow, T. G., Pelicci, P. G., and Di Fiore, P. P. (1999) J. Cell Biol. 147 1379–1384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Beer, T., Hoofnagle, A. N., Enmon, J. L., Bowers, R. C., Yamabhai, M., Kay, B. K., and Overduin, M. (2000) Nat. Struct. Biol. 7 1018–1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neurath, A. R., Strick, N., Jiang, S., Li, Y. Y., and Debnath, A. K. (2002) BMC Infect. Dis. 2 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Rosny, E., Vassell, R., Jiang, S., Kunert, R., and Weiss, C. D. (2004) J. Virol. 78 2627–2631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pho, M. T., Ashok, A., and Atwood, W. J. (2000) J. Virol. 74 2288–2292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stang, E., Kartenbeck, J., and Parton, R. G. (1997) Mol. Biol. Cell 8 47–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brodsky, F. M., Chen, C. Y., Knuehl, C., Towler, M. C., and Wakeham, D. E. (2001) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 17 517–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bosch, B., Clotet-Codina, I., Blanco, J., Pauls, E., Coma, G., Cedeno, S., Mitjans, F., Llano, A., Bofill, M., Clotet, B., Piulats, J., and Este, J. A. (2006) Antiviral Res. 69 173–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boge, M., Wyss, S., Bonifacino, J. S., and Thali, M. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 15773–15778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Byland, R., Vance, P. J., Hoxie, J. A., and Marsh, M. (2007) Mol. Biol. Cell 18 414–425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shu, W., Ji, H., and Lu, M. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 1839–1845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sackett, K., and Shai, Y. (2003) J. Mol. Biol. 333 47–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benferhat, R., Sanchez-Martinez, S., Nieva, J. L., Briand, J. P., and Hovanessian, A. G. (2008) Mol. Immunol. 45 1963–1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Itoh, T., Koshiba, S., Kigawa, T., Kikuchi, A., Yokoyama, S., and Takenawa, T. (2001) Science 291 1047–1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang, H., Traub, L. M., Weixel, K. M., Hawryluk, M. J., Shah, N., Edinger, R. S., Perry, C. J., Kester, L., Butterworth, M. B., Peters, K. W., Kleyman, T. R., Frizzell, R. A., and Johnson, J. P. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 14129–14135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]