Abstract

Growth of a glutamate transport-deficient mutant of Rhodobacter sphaeroides on glutamate as sole carbon and nitrogen source can be restored by the addition of millimolar amounts of Na+. Uptake of glutamate (Kt of 0.2 μM) by the mutant strictly requires Na+ (Km of 25 mM) and is inhibited by ionophores that collapse the proton motive force (pmf). The activity is osmotic-shock-sensitive and can be restored in spheroplasts by the addition of osmotic shock fluid. Transport of glutamate is also observed in membrane vesicles when Na+, a proton motive force, and purified glutamate binding protein are present. Both transport and binding is highly specific for glutamate. The Na+-dependent glutamate transporter of Rb. sphaeroides is an example of a secondary transport system that requires a periplasmic binding protein and may define a new family of bacterial transport proteins.

Keywords: binding protein, secondary transport, sodium, proton motive force

Rhodobacter sphaeroides is a phototrophic, Gram-negative, mesophilic bacterium that can grow on a wide variety of compounds aerobically in the dark and anaerobically in the light. For the uptake of nutrients such as amino acids, this organism mainly relies on binding protein-dependent transport systems rather than secondary transport systems (1). Binding protein dependent transport systems were first identified by Heppel et al. (2), who showed that these systems are osmotic shock-sensitive due to the release of a substrate-binding protein from the periplasmic space. These transport systems belong to the family of ATP binding cassette (ABC) proteins (3–5) and have been studied in great detail in cells, membrane vesicles, and in purified and reconstituted form. Typically, they are multisubunit systems that consist of a soluble periplasmic substrate binding protein that interacts with a membrane protein complex composed of two identical or homologous integral membrane proteins and two identical or homologous ATP-binding proteins. Transport requires the hydrolysis of ATP (4) and is blocked by vanadate, an inhibitor of P-type ATPases (6). Binding protein-dependent systems often exhibit a much higher affinity for the substrate as compared with secondary transport systems, and do not require the proton motive force (pmf) as a driving force for transport (3, 4, 5, 7).

Uptake of the anionic amino acids glutamate and aspartate and their respective amides glutamine and asparagine by Rb. sphaeroides occurs via a single ABC transport system (8) that utilizes two distinct binding proteins with specificity for glutamate/glutamine and aspartate/asparagine, respectively. We have previously isolated a mutant, strain MJ7, that is defective in this ABC-glutamate transporter and is unable to grow on glutamate as carbon (C-) and nitrogen (N-) source (9). Both growth and transport of glutamate can be restored by expressing the Escherichia coli GltP, a secondary H+:glutamate transport system, in Rb. sphaeroides MJ7 (9).

We now show that growth of Rb. sphaeroides strain MJ7 on glutamate can also be restored by the inclusion of millimolar amounts of Na+ in the medium. This phenomenon is due to the activation of an osmotic shock-sensitive transport system that is monospecific for glutamate and that is inhibited by ionophores that collapse the pmf. Further studies in membrane vesicles indicate that glutamate is transported by a novel transport mechanism which requires the presence of a specific glutamate binding protein and Na+ ions and is driven by pmf rather than by the hydrolysis of ATP. To our knowledge, this is the first biochemical demon-stration of a secondary transport system that requires a periplasmic binding protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions.

The following derivatives of Rb. sphaeroides 2.4.1. (10) were used: 4P1, streptomycin resistant (Smr) (10); MJ7, Sm and kanamycin resistant (Kmr), a glutamate transport defective derivative of 4P1 (9); MJ7/GltP, tetracyclin resistant (Tcr), which harbors pMJ100 with gltP under control of the putative Rb. sphaeroides promoter of cytochrome c2 (9); and MJ2, Sm and spectinomycin resistant (Spr). Cells were grown under limiting oxygen or light conditions because then a high sodium stimulated glutamate transport activity was found. Growth was at 30°C on Sistrom medium with succinate and ammonium chloride (11) or with 30 mM glutamate as C and N source. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: Sm, 50 μg/ml; Sp, 50 μg/ml; Km, 25 μg/ml; and Tc, 1 μg/ml.

Construction of a Glutamate Transport Mutant.

The glutamate transport mutant of Rb. sphaeroides MJ7 can only be maintained in the presence of 1 mM γ-glutamylhydrazide, a toxic glutamine analogue. Therefore, a stable mutant was constructed by genetic techniques. A XhoI digest of chromosomal DNA of Rb. sphaeroides 2.4.1. was cloned into pVK100 (12) and conjugated into strain MJ7 via transduction from E. coli S-17 {thi pro hsdR hsdM+ recA, chromosomal insertion of [RP4-2 (Tc::Mu) (Km::Tn7)]} (13). Tcr cells were selected for growth on glutamate as C and N source. A 10-kb chromosomal DNA fragment was isolated that complemented the growth and glutamate transport deficiency of Rb. sphaeroides MJ7 after reconjugation. BamHI digestion of the 10-kb fragment yielded a 2.5-kb fragment† that was further subcloned into pWSK29 (14) in conjunction with a Spr cassette (15), and integrated into the chromosome of Rb. sphaeroides 4P1 by transduction with E. coli S-17. Spr transductants were grown on Sistrom medium (11) yielding the regulation mutant strain MJ2, that exhibited a 3-fold reduced transport activity of the glutamate/glutamine binding protein dependent system and a 6-fold higher level of Na+-stimulated glutamate transport as compared with the parental strain. Sequence analysis of the 2.5-kb fragment did not reveal the presence of a genes coding for a binding protein-dependent system.

Membrane Vesicle Isolation.

Membrane vesicles were isolated from MJ2 cells grown under low oxygen tension (16), stored in liquid N2, and before use, thawed rapidly and extruded through 400 nm polycarbonate filters (17).

Transport Assays.

Transport studies with EDTA-treated (18) or osmotically shocked cells (8) were performed at 30°C as described (19). Cells harvested during logarithmic growth were washed twice in 10 mM Hepes·KOH (pH 8), containing 5 mM MgSO4 and 50 μg/ml chloramphenicol. l-[14C]Glutamate (specific activity, 10.5 TBq/mol) was used at final concentration of 0.94 μM, unless indicated otherwise. Spheroplasts were prepared as described (8).

Transport studies with membrane vesicles (0.3 mg of protein) were done in 20 mM KPi (pH 7) (45 μl final volume) at 30°C under continuous aeration. A pmf was generated by illumination with a 60-W light bulb at 10–15 cm distance and by the addition of 0.2 M K-ascorbate (pH 7), 10 mM N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylphenylene diamine (TMPD), and 50 μM cytochrome c. The presence of both energy sources allowed the highest rates of uptake. Uptake was initiated by the addition of 17 μg or 18 μg, respectively, of partially purified and purified glutamate binding protein, 80 mM NaCl and 3.1 μM l-[14C]glutamate. At various times, the suspension was filtered on 0.15 μm celluloseacetate filters.

Isolation of the Glutamate Binding Protein.

MJ2 cells were resuspended in Tris·HCl, pH 8.0, 20 mM EDTA, and 20% (wt/vol) sucrose. After 10 min incubation at 21°C, cells were shocked by dilution into 30–50 volumes of demineralized water of 4°C. Shocked cells were removed by centrifugation (20,000 × g for 30 min), and the supernatant was concentrated by ultrafiltration (Amicon YM10). Protein was loaded on a MonoQ column HR10/10 connected to a Pharmacia fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) system, and fractionated by a linear gradient of 0–0.4 M KCl (50 ml) in 10 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.0) at an elution rate of 1 ml/min. Fractions were tested for l-[14C]glutamate (1.87 μm, 10.5 TBq/ml) binding as described (8). Two active pools were found—i.e., at 350 mM KCl corresponding to the glutamate/glutamine binding protein previously purified and characterized (8) and at 150 mM KCl with specificity for glutamate only. The latter fractions were either used in transport studies or loaded on a Phenyl-Superose column 5/5 and fractionated by a linear gradient of 1.2–0.6 M (NH4)2SO4 (50 ml) in 10 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.0). Active fractions were concentrated, and the buffer was replaced for 50 mM KPi (pH 7.5) by ultrafiltration. Purity was assessed by SDS/PAGE on 12.5% gels according to a standard method (20).

Other Procedures.

The protein concentration was determined by the method of Lowry et al. (21) using bovine serum albumin as a standard.

RESULTS

Sodium-Stimulated Uptake of Glutamate by a Transport Mutant of Rh. sphaeroides.

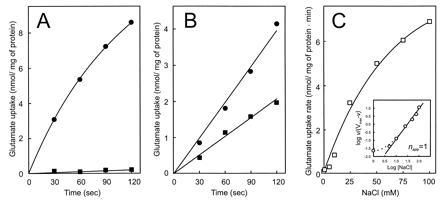

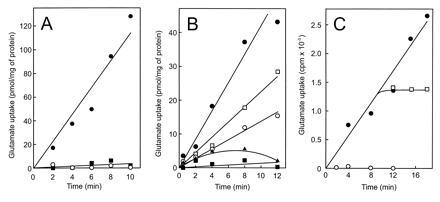

Tn5 insertion mutagenesis has allowed the isolation of a mutant of Rb. sphaeroides 4P1, strain MJ7, that is unable to grow on glutamate as sole C and N source (9). This mutant is defective in the ABC transporter for glutamate, aspartate, and the respective amides, and exhibits a severely reduced glutamate uptake activity (9) (Fig. 1A). However, the presence of 30 mM Na-glutamate instead of K-glutamate in the medium allowed growth of these cells. NaCl also restored the ability of these cells to accumulate glutamate (Fig. 1A). The rate of uptake increased with the Na+ concentration and was half-maximal at about 25 mM Na+ (Fig. 1C). The Hill plot for the stimulatory effect of Na+ (Fig. 1C Inset) showed a slope of one. The effect is specific for Na+ and is not due to osmotic effects as LiCl, KCl, and sorbitol at the same osmolarity value were unable to stimulate glutamate transport.

Figure 1.

Na+-stimulated glutamate transport by Rb. sphaeroides. (A) Glutamate transport by strain MJ7 in the absence (▪) and presence (•) of 100 mM NaCl. (B) Glutamate transport by strain 4P1 in the absence (▪) and presence (▾) of 100 mM NaCl. (C) Effect of Na+ on the glutamate transport activity by strain MJ7 (□). The ionic strength was balanced by KCl. (Inset) Hill plot.

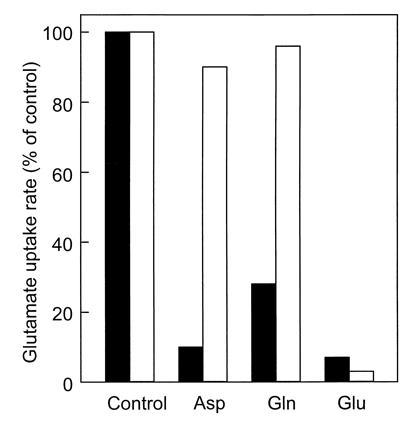

The uptake of glutamate by wild-type Rb. sphaeroides 4P1 cells was also stimulated by Na+ ions, but unlike the mutant, transport was not strictly dependent on Na+ ions (Fig. 1B). A 100-fold excess of glutamine and aspartate had no effect on the Na+-stimulated glutamate transport by MJ7 cells but dramatically reduced the Na+-independent glutamate transport activity in strain 4P1 (Fig. 2). Na+-stimulated glutamate uptake by strain MJ7 occurred with an extremely high affinity for glutamate—i.e., a Kt of 0.2 ± 0.05 μM and a Vmax of 11.8 nmol/mg of protein/min. The rate of Na+-stimulated glutamate uptake increased more than 40-fold when the external pH was elevated from 6.0 to 7.5 (pKapp of 6.7) (data not shown). These data suggest that Rb. sphaeroides contains, in addition to a glutamate/glutamine uptake system (8), a glutamate uptake system that is highly specific for glutamate and is stimulated by Na+ ions.

Figure 2.

Effect of competing substrates on Na+-stimulated glutamate uptake by Rb. sphaeroides MJ7 (open bars) and Na+-independent glutamate uptake by Rb. sphaeroides 4P1 (solid bars). [14C]Glutamate and unlabeled substrates were used at concentrations of 3.1 μM and 0.3 mM, respectively.

Sodium-Stimulated Transport of Glutamate Is Osmotic Shock Sensitive and Inhibited by Ionophores.

Na+-stimulated glutamate transport by strain MJ7 was compared with the uptake of glutamate in the absence of Na+ ions by the wild-type strain 4P1 and by MJ7 transformed with pMJ100 harboring the E. coli gltP gene (9). In the wild type, glutamate uptake is mediated by a binding protein-dependent system (8), while in MJ7/GltP, uptake of glutamate is catalyzed by GltP (9), a secondary transport system that mediates glutamate uptake in symport with two protons (22). Na+-stimulated glutamate uptake by MJ7 cells was not affected by vanadate (Table 1), an inhibitor of ATP-driven transport systems (6). However the ionophores valinomycin and nigericin that dissipate the pmf blocked Na+-stimulated glutamate transport (Table 1). In contrast, vanadate completely prevented glutamate uptake in 4P1 cells, while the ionophores valinomycin and nigericin had no effect. GltP-mediated glutamate transport, on the other hand, was blocked by the ionophores but not affected by vanadate.

Table 1.

Effect of osmotic shock treatment, inhibitors, and ionophores on l-glutamate transport in Rb. sphaeroides

| Treatment/addition | Initial rate of glutamate

uptake,* % of control

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| MJ7† | 4P1‡ | MJ7/GltP‡ | |

| Osmotic shock treatment | 10 | 17 | 98 |

| Vanadate, 1 mM | 98 | 5 | 100 |

| Ionophores | |||

| Valinomycin, 3.6 nM | 15 | 104 | 13 |

| Nigericin 5.3 nM | 21 | 101 | 10 |

| Valinomycin, 3.6 nM, plus | |||

| nigericin 5.3 nM | 5 | 117 | 4 |

Absolute transport rates for strains MJ7, 4P1, and MJ7/GltP were, respectively, 5.4, 1.0, and 0.87 nmol/mg of protein per min. Uptake was measured at 0.94 μM glutamate.

In the presence of 80 mM NaCl.

In the absence of NaCl.

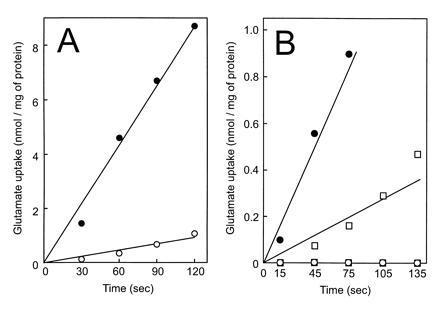

As a final test to discriminate between a secondary and a binding protein-dependent transport mechanism, cells were subjected to an osmotic shock. This treatment not only abolished the binding protein-dependent transport of glutamate by 4P1 cells (8) (Table 1), but surprisingly completely blocked Na+-stimulated glutamate uptake by MJ7 cells, while GltP-mediated transport was not affected. Na+-stimulated glutamate uptake activity of spheroplasts derived from MJ7 cells was partially restored by the addition of periplasmic fraction (Fig. 3). These findings suggest that a binding protein is involved in Na+-stimulated uptake of glutamate, while the effects of vanadate and ionophores argue in favor of a role of the pmf as driving force for transport.

Figure 3.

Osmotic shock sensitivity of Na+-stimulated glutamate uptake in Rb. sphaeroides MJ7. (A) Glutamate uptake by osmotic-shocked (○) and nonshocked cells (•) in the presence of 80 mM NaCl. (B) Glutamate uptake by spheroplasts in the presence (•, ○) or absence (▪, □) of periplasmic fraction with 80 mM NaCl (solid symbols) or KCl (open symbols).

Sodium-Stimulated Glutamate Transport in Membrane Vesicles Is Binding Protein-Dependent and pmf-driven.

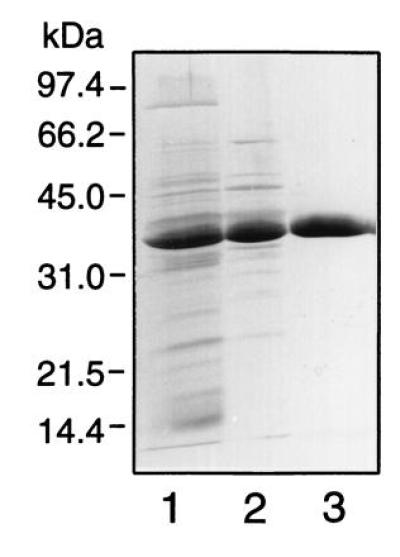

The energetic mechanism of Na+-stimulated glutamate transport was further studied with membrane vesicles derived from Rb. sphaeroides MJ2 cells. To restore binding protein-dependent transport in these membrane vesicles, a novel glutamate binding protein with a apparent Mr of 35 kDa was purified from the osmotic shock fluid of strain MJ2 (Fig. 4). The specific activity, as measured in a transport assay with membrane vesicles (see below), was 0.2 and 12 pmol/mg of protein/min for the osmotic shock fluid and purified protein, respectively. The final yield was 78%. The protein binds glutamate with a Kd of 1.2 μM. It differs from the glutamate/glutamine binding protein described previously (8) as it eluted at a different position during ion-exchange chromatography while it is specific for glutamate only—i.e., binding of l-[14C]glutamate was inhibited by a 100-fold excess of l- (97%) and d-glutamate (60%), but hardly by aspartate (19%), asparagine (13%), and glutamine (9%). Glutamate binding was not stimulated by Na+ ions up to a concentration of 100 mM. Membrane vesicles isolated from MJ2 cells grown under limiting oxygen conditions were energized by light and the electron donors ascorbate, TMPD, and cytochrome c. Uptake of glutamate by these membrane vesicles was only observed when a high concentration of Na+ ions and purified binding protein was added (Fig. 5A). Uptake was low in the absence of binding protein (○) or when Na+ was replaced for K+. The previously characterized glutamate/glutamine binding protein (8) could not substitute for the glutamate binding protein (data not shown). When the membrane vesicles were incubated in the dark and in the absence of electron donors, no glutamate uptake was observed (Fig. 5B). In the presence of nigericin, valinomycin, monensin, or nonactin (data not shown), the uptake activity was reduced and nearly completely blocked in the presence of the uncoupler carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP). Transport is highly specific for glutamate as the uptake of [14C]glutamate was abolished by a 50-fold excess of nonradioactive glutamate (98%), but not by aspartate (0%) and only slightly by glutamine (17%). Accumulated [14C]glutamate was not released from the membrane vesicles upon the addition of a 500-fold excess of unlabeled glutamate (Fig. 5C). These data demonstrate that the Na+-stimulated glutamate uptake activity is mediated by a binding protein-dependent system that requires the pmf as a driving force.

Figure 4.

Purification of the glutamate binding protein. Shown are results of SDS/PAGE (12.5% polyacrylamide gel) of periplasmic protein (lane 1), and the pool of active fractions after Mono Q (lane 2) and the phenyl-superose (lane 3) column chromatography. All lanes contained 3 μg of protein.

Figure 5.

Glutamate transport in membrane vesicles of Rb. sphaeroides MJ2. (A) Uptake of l-[14C]glutamate (3.1 μM) in the presence of 18 μg of purified glutamate binding protein with 80 mM Na+ (•) or K+ ions (▪) and without binding protein with Na+ ions (○). Membrane vesicles were energized by light and the electron donor system ascorbate, TMPD, and cytochrome c. (B and C) Reactions were performed with 17 μg of partially purified binding protein and 80 mM Na+ ions. (B) Effect of valinomycin (□), nigericin (○), and carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP) (▴) on glutamate uptake (3.1 μM) in membrane vesicles incubated with (•, □, ○, ▴) or without (▪) light, ascorbate, TMPD, and cytochrome c. (C) Uptake of l-[14C]glutamate (3.1 μM) in the absence (•) and presence of unlabeled glutamate added in 500-fold excess at t = 0 (○) or t = 11 min (□).

DISCUSSION

This paper presents evidence that Rb. sphaeroides contains a Na+-stimulated glutamate transport system that is distinct from any other bacterial secondary transport system characterized thus far. Transport is driven by the pmf, but strictly requires the presence of a periplasmic glutamate binding protein. All binding protein-dependent transport systems described so far belong to the family of ABC transporters. The system found in Rb. sphaeroides does not fit in this category as ATP is not needed for transport in membrane vesicles. Moreover, vanadate had no effect on Na+-stimulated glutamate transport by intact cells. Our experiments failed to demonstrate exchange of glutamate in membrane vesicles, suggesting that the system functions unidirectional. This is typical for binding protein-dependent systems (3, 4) but is not commonly observed for secondary transport systems (7). It is concluded that the Na+-stimulated glutamate transport system is a member of a new class of binding protein-dependent transport system that utilizes the pmf as driving force.

The newly described transport system is distinct from the previously characterized glutamate/glutamine binding protein-dependent transport system of Rb. sphaeroides (8). The latter system exhibits a broader substrate specificity, utilizes a different binding protein, is inhibited by vanadate and not stimulated by Na+-ions, is not dependent on the external pH, and does not require the pmf as driving force. The genes coding for a ABC–glutamate transport system have recently been cloned of Rb. capsulatus (Z. Zheng and R. Haselkorn, personal communications). Wild-type Rb. sphaeroides cells express both transport systems, but in the transport mutant MJ7, only the Na+-stimulated transport system is present. It is not clear whether Na+ is cotransported with glutamate, or whether it only stimulates transport for instance via an allosteric effect. Na+ is not required for binding of glutamate to the binding protein. The Hill plot of the stimulatory effect of Na+ on transport (Fig. 1C) indicates a slope of 1, which points to the presence of a single sodium binding site. This site has an extreme poor but highly specific affinity for Na+, as Na+ could not be replaced by Li+. Na+ binding affinities in the millimolar range have been reported before for transporters (23). The inhibitory effect of the protono- and ionophores demonstrate that at least the transmembrane electrical potential (Δψ) function as driving forces for glutamate uptake. A transport mechanism of glutamate via a H+:Na+ symport as observed in Bacillus stearothermophilus (22) or 2H+ (and an allosteric Na+ stimulation) can explain these observations, although a Na+ symport mechanism without the involvement of H+ as coupling ion cannot yet be ruled out. A precise analysis of the energetics of glutamate uptake and coupling ion stoichiometry awaits purification and reconstitution of this transport system and the use of artifically imposed ion gradients.

In Rb. sphaeroides, the uptake of important carbon sources as succinate and malate is also stimulated by 100 mM NaCl (unpublished results). Interestingly, uptake of these substrates is not inhibited by vanadate (1). In the related purple nonsulfur bacterium Rb. capsulatus, both genetic and biochemical evidence indicates that malate transport proceeds via a binding protein dependent transport system (24, 25). The dct locus contains two genes that code for components of this transport system—i.e., dctP (binding protein) and dctQ (a large hydrophobic integral membrane protein)—but does not contain a gene encoding an ABC protein (26). Homologs of these C4-dicarboxylate transporter genes exist in E. coli, Haemophilus influenza, and various other Gram-negative bacteria. Indirect evidence has led to the suggestion that malate transport in Rb. capsulatus may not be driven by ATP hydrolysis but by the Δψ (26). This system may as well belong to the new class of secondary transport systems that are binding protein- and pmf-dependent.

The observation that periplasmic binding proteins are not only associated with ATP-driven transporters but also with secondary transporters clearly has some important implications for our understanding of the evolution of multicomponent transport systems (27). One may hypothesize that these systems arose from secondary transport systems that have acquired a binding protein to allow a high-affinity interaction with the substrate. Alternatively, this system may have functioned as typical binding protein-dependent systems, but at some point in evolution may have hijacked an integral membrane domain(s) to allow a different mechanism of energy coupling.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Netherlands Foundation of Chemical Research (S.O.N.) with financial support of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (N.W.O.).

Footnotes

Abbreviations: TMPD, N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylphenylene diamine; ABC, ATP binding cassette; pmf, proton motive force; Smr, streptomycin resistant; Kmr, kanamycin resistant; Tcr, tetracyclin resistant; Spr, spectinomycin resistant; Δψ, transmembrane electrical potential.

DNA sequence analysis of the 2.5-kb fragment did not reveal the presence of genes coding for a binding protein-dependent system. This fragment most likely harbors genes involved in the regulation of the expression of the glutamate transport systems.

References

- 1.Abee T. Ph.D. thesis. Groningen, The Netherlands: Univ. of Groningen; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heppel L A, Rosen B P, Friedberg I, Berger E A, Weiner J H. In: The Molecular Basis of Biological Transport. Woessner J F Jr, Huijing F, editors. New York: Academic; 1972. pp. 133–156. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Higgins C F. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1992;8:67–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.08.110192.000435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ames G F-L. In: The Bacteria. Krulwich T A, editor. Vol. 12. New York: Academic; 1990. pp. 225–246. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nikaido H. FEBS Lett. 1994;346:55–58. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00315-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richarme G, Abdelhamid E Y, Kohiyama M. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:9473–9477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poolman B, Molenaar D, Konings W N. In: Handbook of Biomembranes: Structural and Functional Aspects. Shintzky M, editor. Vol. 2. Rehovot, Israel: Balaban; 1994. pp. 329–379. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacobs M H J, Driessen A J M, Konings W N. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1812–1816. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.7.1812-1816.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobs M H J, van der Heide T, Tolner B, Driessen A J M, Konings W N. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:641–647. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18040641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nano F E. Ph.D. thesis. Urbana: Univ. of Illinois; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sistrom W R. J Gen Microbiol. 1960;22:778–785. doi: 10.1099/00221287-22-3-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knauf V C, Nester E W. Plasmid. 1982;8:45–54. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(82)90040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simon R, Priefer V, Puhler A. Bio/Technology. 1983;1:784–791. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang R F, Kushner S R. Gene. 1991;100:195–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Felley R, Frey F J, Krisch H. Gene. 1987;52:147–154. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaback H R. Methods Enzymol. 1971;22:99–120. [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacDonald R C, MacDonald R I, Menco B P M, Takeshita K, Subbarao N K, Hu L-R. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1061:297–303. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(91)90295-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elferink M G L, Hellingwerf K J, Konings W N. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;848:58–68. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abee T, van der Wal F-J, Hellingwerf K J, Konings W N. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5148–5154. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.9.5148-5154.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laemmli U K. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowry O H, Rosebrough N J, Farr A L, Randall R J. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tolner B, Poolman B, Konings W N. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:2845–2856. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maloy S R. In: The Bacteria. Krulwich T A, editor. Vol. 12. New York: Academic; 1990. pp. 203–224. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shaw J G, Hamblin M J, Kelly D J. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:3055–3062. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaw J G, Kelly D J. Arch Microbiol. 1991;155:466–472. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forward J A, Behrendt M C, Kelly D J. Biochem Soc Trans. 1993;21:3438. doi: 10.1042/bst021343s. (abstr.). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saier M H. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:71–93. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.1.71-93.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]