Abstract

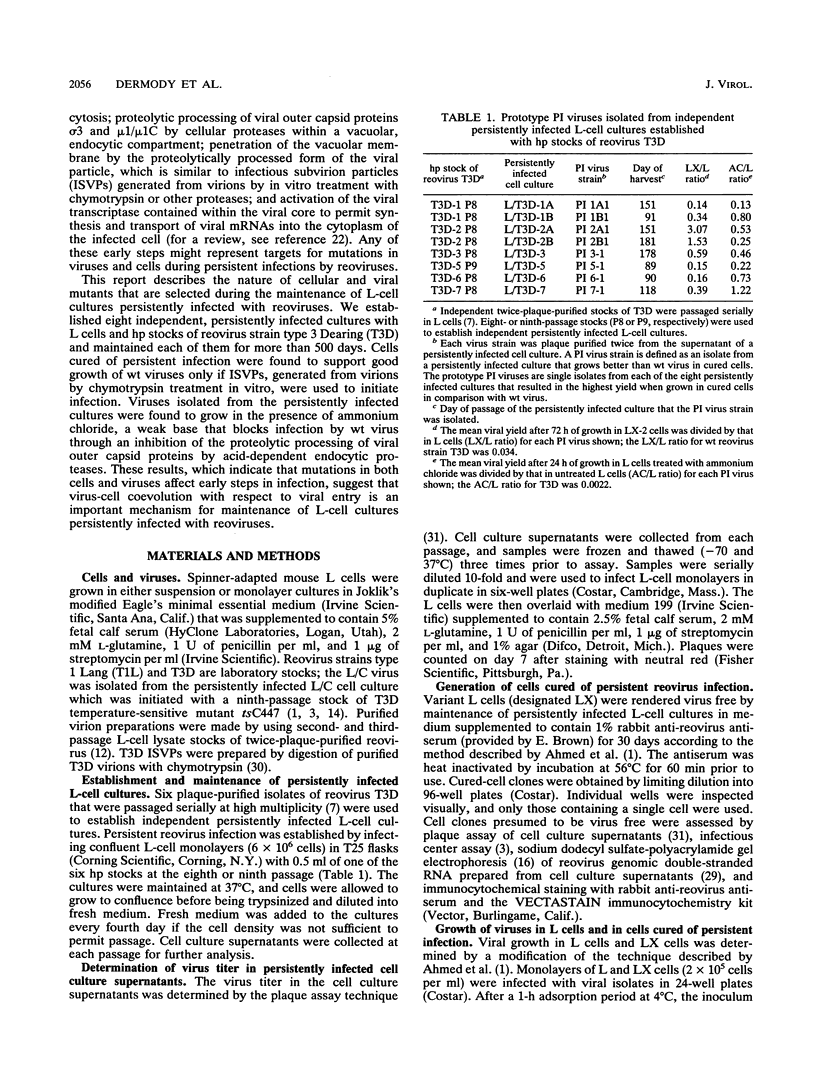

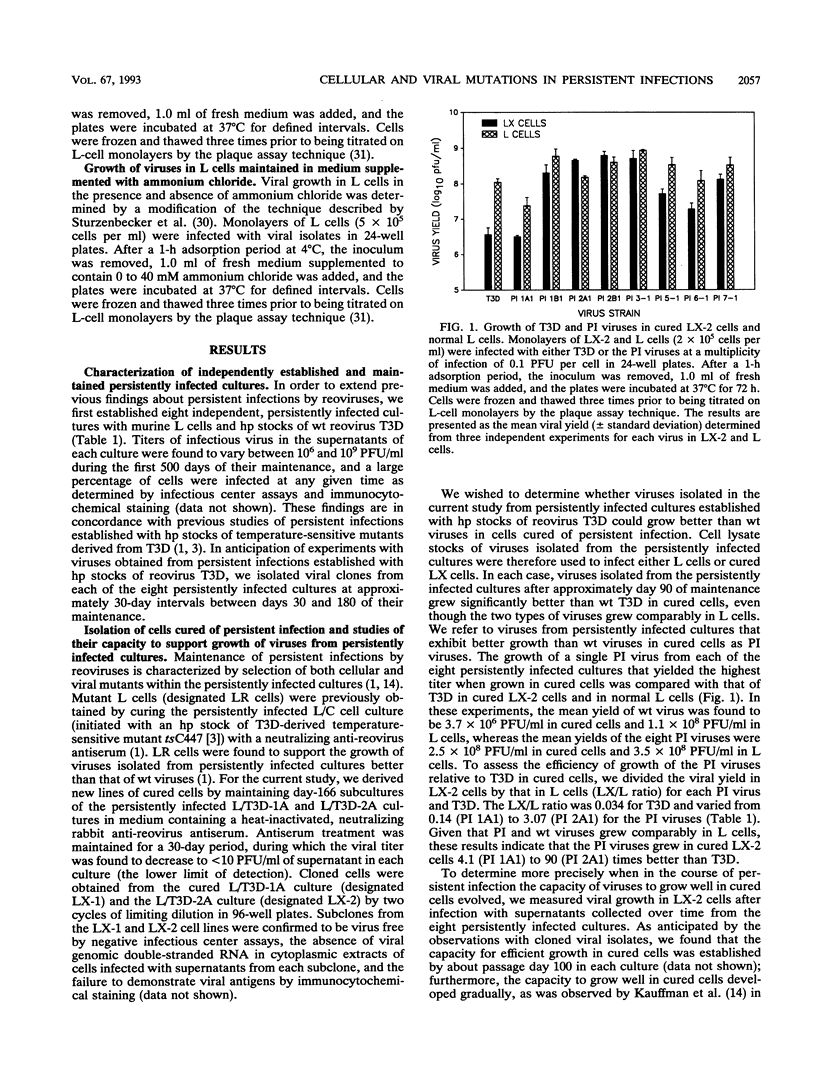

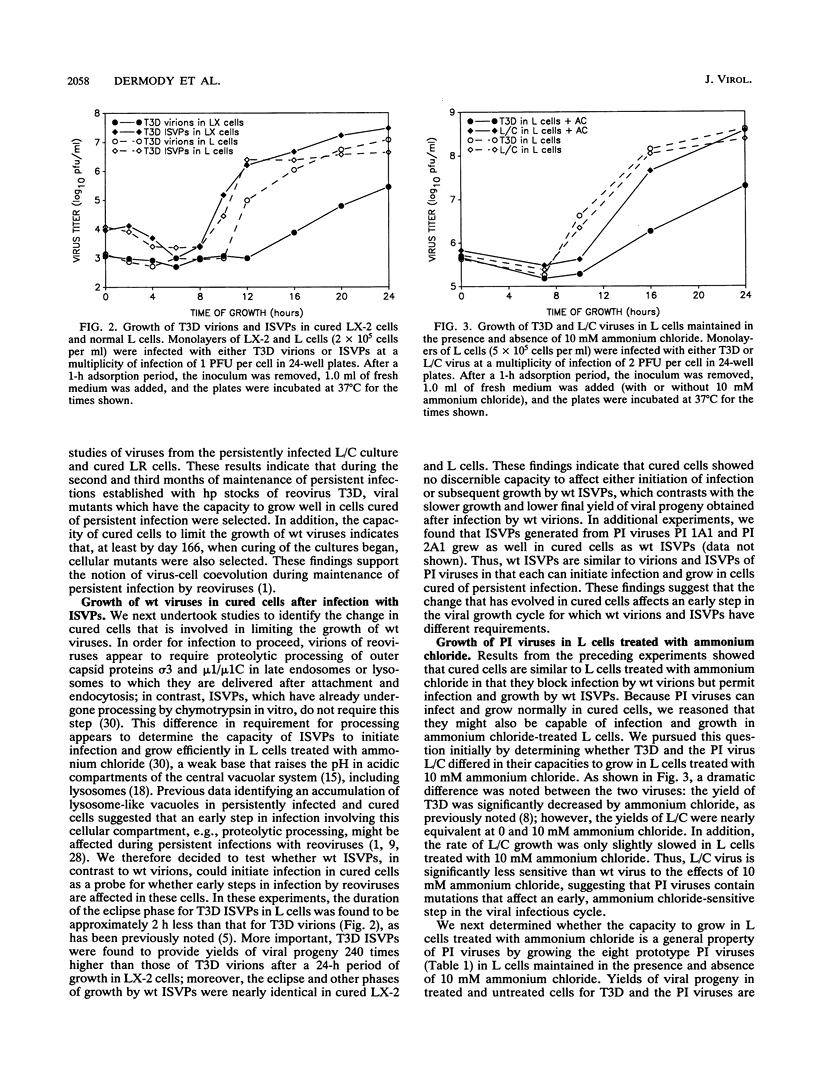

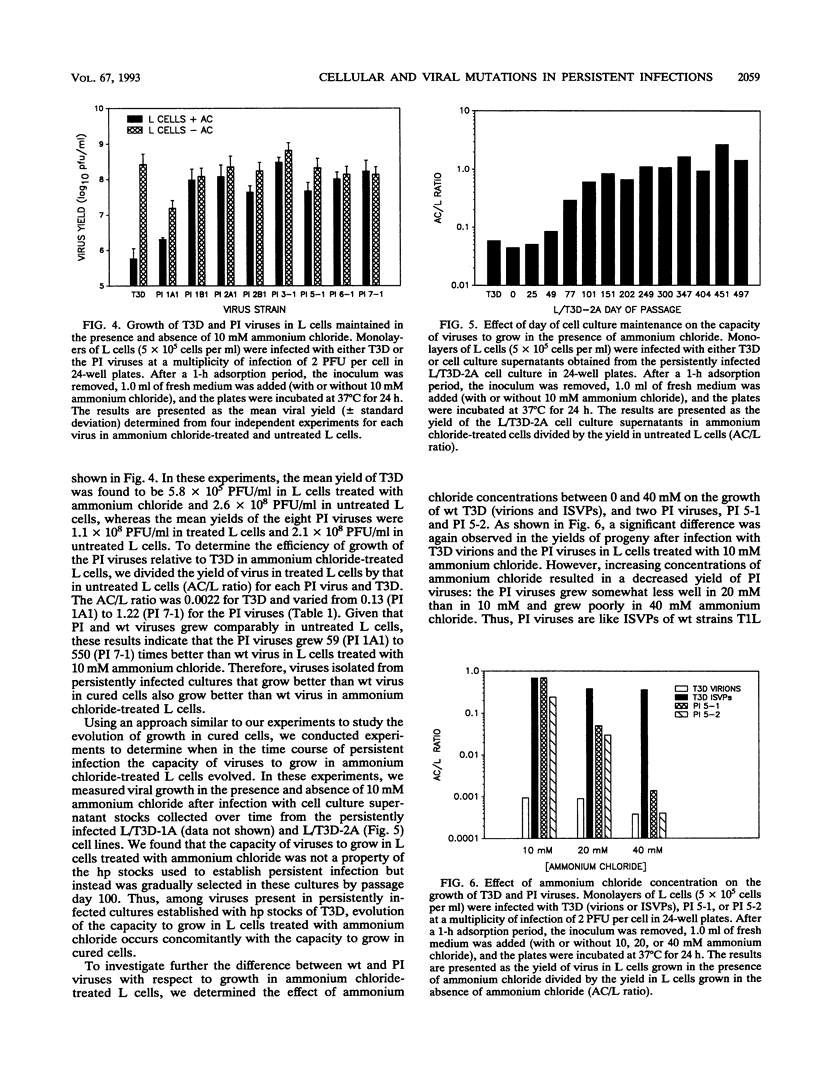

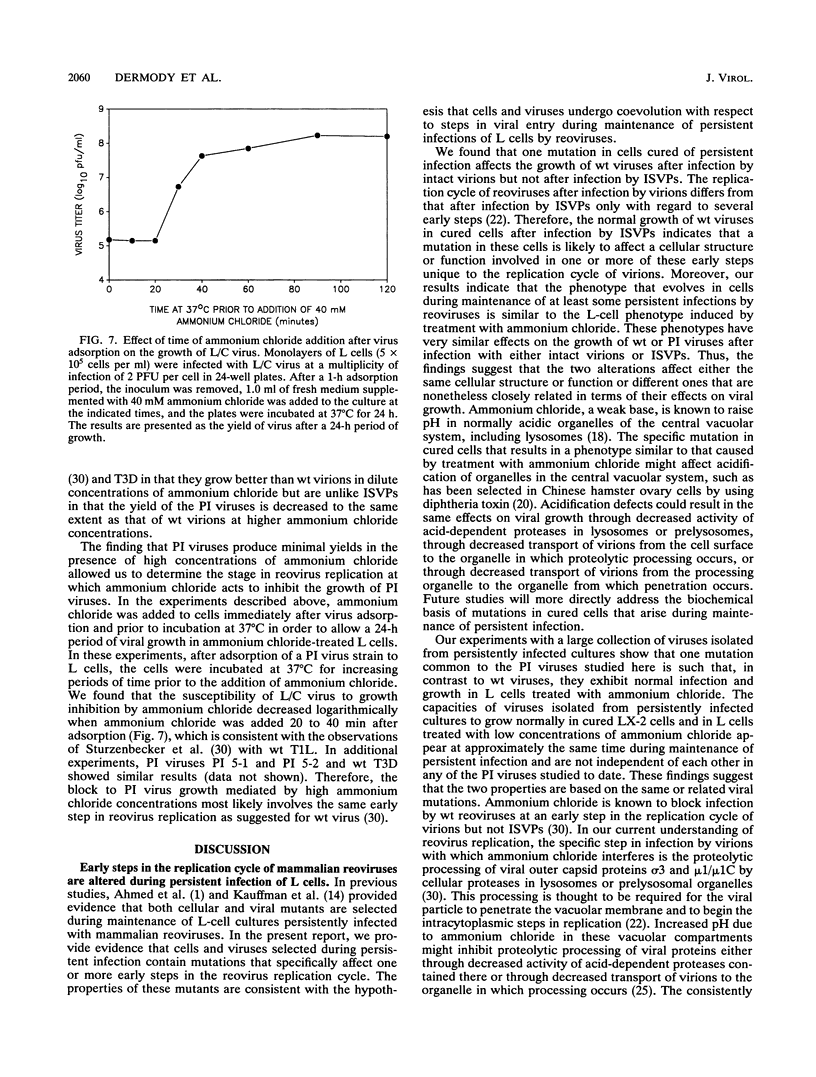

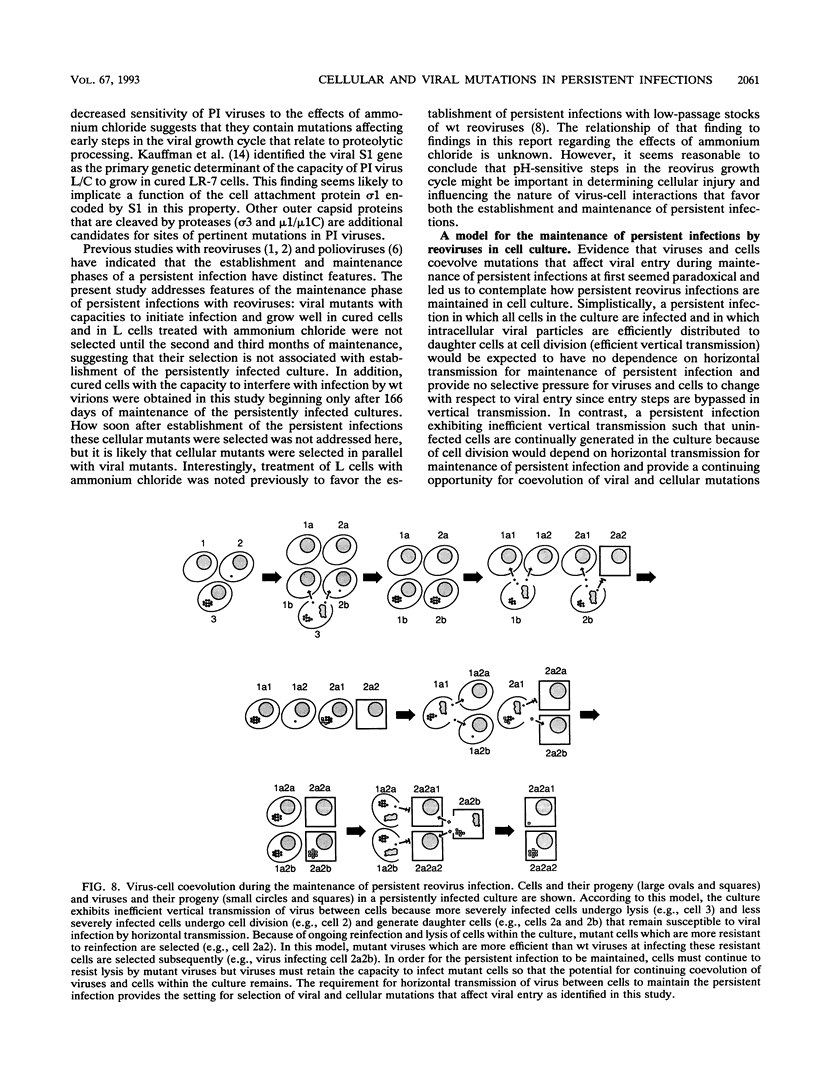

Previous studies demonstrated that both cellular and viral mutants are selected during maintenance of persistent infections established in murine L cells with high-passage stocks of mammalian reoviruses. In particular, when one culture was cured of persistent infection, the resulting cells were found to support the growth of viruses isolated from persistently infected cultures (termed PI viruses here) better than that of wild-type (wt) viruses (R. Ahmed, W. M. Canning, R. S. Kauffman, A. H. Sharpe, J. V. Hallum, and B. N. Fields, Cell 25:325-332, 1981). To address the nature of cellular and viral mutations selected during maintenance of persistent reovirus infections, we established independent, persistently infected cultures with L cells and high-passage stocks of wt reovirus. These cultures served as sources of new PI viruses and cured cells for study. We found that although wt viruses grew poorly in cured cells when infection was initiated with intact virions, they grew well in cured cells when infection was initiated with infectious subvirion particles generated from virions by in vitro treatment with chymotrypsin. This finding indicates that the block to growth of wt viruses in cured cells involves an early step that is unique to infection by virions, such as proteolytic processing in an endocytic compartment. We also found that PI viruses grew better than wt viruses in L cells treated with ammonium chloride, a weak base that inhibits the pH decrease in endosomes and lysosomes. Because ammonium chloride blocks an early step in infection by intact virions, probably the proteolytic processing of viral outer capsid proteins by acid-dependent cellular proteases in late endosomes or lysosomes, this finding indicates that PI viruses differ from wt viruses with respect to viral entry into cells. Therefore, these results indicate that both cells and viruses evolve mutations that affect one or more early steps in the viral growth cycle during maintenance of L-cell cultures persistently infected with reoviruses.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Ahmed R., Canning W. M., Kauffman R. S., Sharpe A. H., Hallum J. V., Fields B. N. Role of the host cell in persistent viral infection: coevolution of L cells and reovoirus during persistent infection. Cell. 1981 Aug;25(2):325–332. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed R., Fields B. N. Role of the S4 gene in the establishment of persistent reovirus infection in L cells. Cell. 1982 Mar;28(3):605–612. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90215-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed R., Graham A. F. Persistent infections in L cells with temperature-sensitive mutants of reovirus. J Virol. 1977 Aug;23(2):250–262. doi: 10.1128/jvi.23.2.250-262.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsa J., Sargent M. D., Lievaart P. A., Copps T. P. Reovirus: evidence for a second step in the intracellular uncoating and transcriptase activation process. Virology. 1981 May;111(1):191–200. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(81)90664-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borzakian S., Couderc T., Barbier Y., Attal G., Pelletier I., Colbère-Garapin F. Persistent poliovirus infection: establishment and maintenance involve distinct mechanisms. Virology. 1992 Feb;186(2):398–408. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90005-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canning W. M., Fields B. N. Ammonium chloride prevents lytic growth of reovirus and helps to establish persistent infection in mouse L cells. Science. 1983 Feb 25;219(4587):987–988. doi: 10.1126/science.6297010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst H., Shatkin A. J. Reovirus hemagglutinin mRNA codes for two polypeptides in overlapping reading frames. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Jan;82(1):48–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlong D. B., Nibert M. L., Fields B. N. Sigma 1 protein of mammalian reoviruses extends from the surfaces of viral particles. J Virol. 1988 Jan;62(1):246–256. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.1.246-256.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman R. S., Ahmed R., Fields B. N. Selection of a mutant S1 gene during reovirus persistent infection of L cells: role in maintenance of the persistent state. Virology. 1983 Nov;131(1):79–87. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90535-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klausner R. D., Donaldson J. G., Lippincott-Schwartz J. Brefeldin A: insights into the control of membrane traffic and organelle structure. J Cell Biol. 1992 Mar;116(5):1071–1080. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.5.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970 Aug 15;227(5259):680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahy B. W. Strategies of virus persistence. Br Med Bull. 1985 Jan;41(1):50–55. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxfield F. R. Weak bases and ionophores rapidly and reversibly raise the pH of endocytic vesicles in cultured mouse fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1982 Nov;95(2 Pt 1):676–681. doi: 10.1083/jcb.95.2.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae M. A., Joklik W. K. The nature of the polypeptide encoded by each of the 10 double-stranded RNA segments of reovirus type 3. Virology. 1978 Sep;89(2):578–593. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(78)90199-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merion M., Schlesinger P., Brooks R. M., Moehring J. M., Moehring T. J., Sly W. S. Defective acidification of endosomes in Chinese hamster ovary cell mutants "cross-resistant" to toxins and viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983 Sep;80(17):5315–5319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.17.5315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustoe T. A., Ramig R. F., Sharpe A. H., Fields B. N. Genetics of reovirus: identification of the ds RNA segments encoding the polypeptides of the mu and sigma size classes. Virology. 1978 Sep;89(2):594–604. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(78)90200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nibert M. L., Furlong D. B., Fields B. N. Mechanisms of viral pathogenesis. Distinct forms of reoviruses and their roles during replication in cells and host. J Clin Invest. 1991 Sep;88(3):727–734. doi: 10.1172/JCI115369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ron D., Tal J. Coevolution of cells and virus as a mechanism for the persistence of lymphotropic minute virus of mice in L-cells. J Virol. 1985 Aug;55(2):424–430. doi: 10.1128/jvi.55.2.424-430.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar G., Pelletier J., Bassel-Duby R., Jayasuriya A., Fields B. N., Sonenberg N. Identification of a new polypeptide coded by reovirus gene S1. J Virol. 1985 Jun;54(3):720–725. doi: 10.1128/jvi.54.3.720-725.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seglen P. O. Inhibitors of lysosomal function. Methods Enzymol. 1983;96:737–764. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(83)96063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe A. H., Fields B. N. Reovirus inhibition of cellular DNA synthesis: role of the S1 gene. J Virol. 1981 Apr;38(1):389–392. doi: 10.1128/jvi.38.1.389-392.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe A. H., Fields B. N. Reovirus inhibition of cellular RNA and protein synthesis: role of the S4 gene. Virology. 1982 Oct 30;122(2):381–391. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(82)90237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe A. H., Ramig R. F., Mustoe T. A., Fields B. N. A genetic map of reovirus. 1. Correlation of genome RNAs between serotypes 1, 2, and 3. Virology. 1978 Jan;84(1):63–74. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(78)90218-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturzenbecker L. J., Nibert M., Furlong D., Fields B. N. Intracellular digestion of reovirus particles requires a low pH and is an essential step in the viral infectious cycle. J Virol. 1987 Aug;61(8):2351–2361. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.8.2351-2361.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virgin H. W., 4th, Bassel-Duby R., Fields B. N., Tyler K. L. Antibody protects against lethal infection with the neurally spreading reovirus type 3 (Dearing). J Virol. 1988 Dec;62(12):4594–4604. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.12.4594-4604.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Torre J. C., Martínez-Salas E., Diez J., Villaverde A., Gebauer F., Rocha E., Dávila M., Domingo E. Coevolution of cells and viruses in a persistent infection of foot-and-mouth disease virus in cell culture. J Virol. 1988 Jun;62(6):2050–2058. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.6.2050-2058.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]