Abstract

Objective To assess the risk of venous thromboembolism in women using hormone replacement therapy by study design, characteristics of the therapy and venous thromboembolism, and clinical background.

Design Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources Medline.

Studies reviewed Eight observational studies and nine randomised controlled trials.

Inclusion criteria Studies on hormone replacement therapy that reported venous thromboembolism.

Review measures Homogeneity between studies was analysed using χ2 and I2 statistics. Overall risk of venous thromboembolism was assessed from a fixed effects or random effects model.

Results Meta-analysis of observational studies showed that oral oestrogen but not transdermal oestrogen increased the risk of venous thromboembolism. Compared with non-users of oestrogen, the odds ratio of first time venous thromboembolism in current users of oral oestrogen was 2.5 (95% confidence interval 1.9 to 3.4) and in current users of transdermal oestrogen was 1.2 (0.9 to 1.7). Past users of oral oestrogen had a similar risk of venous thromboembolism to never users. The risk of venous thromboembolism in women using oral oestrogen was higher in the first year of treatment (4.0, 2.9 to 5.7) compared with treatment for more than one year (2.1, 1.3 to 3.8; P<0.05). No noticeable difference in the risk of venous thromboembolism was observed between unopposed oral oestrogen (2.2, 1.6 to 3.0) and opposed oral oestrogen (2.6, 2.0 to 3.2). Results from nine randomised controlled trials confirmed the increased risk of venous thromboembolism among women using oral oestrogen (2.1, 1.4 to 3.1). The combination of oral oestrogen and thrombogenic mutations or obesity further enhanced the risk of venous thromboembolism, whereas transdermal oestrogen did not seem to confer additional risk in women at high risk of venous thromboembolism.

Conclusion Oral oestrogen increases the risk of venous thromboembolism, especially during the first year of treatment. Transdermal oestrogen may be safer with respect to thrombotic risk. More data are required to investigate differences in risk across the wide variety of hormone regimens, especially the different types of progestogens.

Introduction

Hormone replacement therapy can improve the quality of life for women with hypo-oestrogenic symptoms.1 Many women are still prescribed oestrogen therapy to treat postmenopausal symptoms despite recent data showing that overall health risks may exceed benefits of long term hormone replacement therapy.2 Hormone replacement therapy is also effective for preventing osteoporotic fractures among current users.2 3 In contrast, harmful effects of hormone replacement therapy include breast cancer and venous thromboembolism.4 Furthermore, randomised controlled trials showed that hormone replacement therapy might increase the risk of coronary heart disease and stroke.2 5

Despite evidence that oral oestrogen activates blood coagulation in postmenopausal women,6 hormone replacement therapy had, until 1996, long been believed to have little effect on the risk of venous thromboembolism.7 Recent observational studies have, however, shown consistent associations between current use of hormone replacement therapy and an increased risk of venous thromboembolism in postmenopausal women.5 w1-w11 These findings have been confirmed by randomised controlled trials.5 w12-w20

Most previous studies of venous thromboembolism in users of hormone replacement therapy were done among women using conjugated equine oestrogens alone or with medroxyprogesterone acetate.8 9 These results cannot be generalised to other regimens of hormone replacement therapy, especially those used in some European countries. Recent data have suggested the importance of the route of oestrogen administration in determining risk of venous thromboembolism.10

The purpose of this review was to estimate the risk of venous thromboembolism among users of hormone replacement therapy. We took into account study design and characteristics of hormone replacement therapy and venous thromboembolism.

Methods

We carried out an electronic search of Medline from 1974 to 2007. Relevant keywords relating to hormone replacement therapy (“estrogen replacement” or “oestrogen replacement” or “estrogen” or “estrogen therapy” or “oestrogen” or “oestrogen therapy” or “estrogen replacement therapy” or “oestrogen replacement therapy” or “hormone” or “hormone replacement therapy” or “hormone therapy” or “hormonal therapy” or “hormonal replacement therapy”) were used in combination with words relating to venous thromboembolism (“venous thrombosis” or “venous thromboembolism” or “thrombosis” or “pulmonary embolism” or “embolism” or “emboli”). We also identified original articles by back referencing from general reviews published after 1970.7 8 9 11 12 13 14 15 16 17

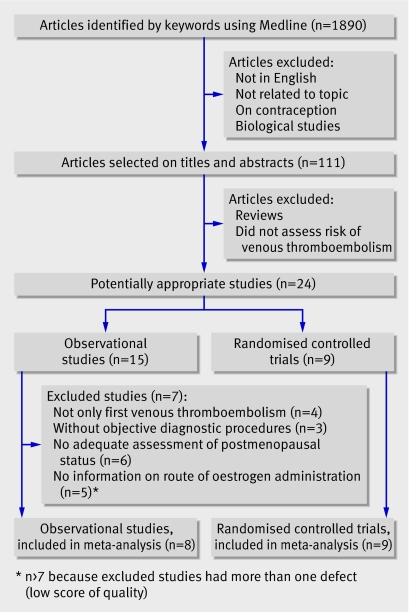

We screened all articles identified through Medline (n=1890). We first excluded publications that were not in English, not related to the topic, on contraception, and biological studies. The selected articles (n=111) were reviewed and we excluded general reviews and articles that did not assess risk of venous thromboembolism. Twenty four studies (nine randomised controlled trials,w12-w20 12 case-control studies,w1-w3 w5-w7 w9-w11 w21-w23 and three prospective cohort studiesw4 w24 w25) were eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis and were assessed for quality.

Quality assessment and data extraction

We assessed the quality of randomised controlled trials and observational studies separately. For randomised controlled trials we assessed for quality of randomisation, blinding, reporting of withdrawals, generation of random numbers, and concealment of allocation. Trials scored one point for each area addressed, with scores between 0 and 5 (highest level of quality)18 19; we included in the meta-analysis trials that scored 4 or higher.w12-w20 We assessed the quality of observational studies using a specific checklist consistent with the consensus recommendations by the Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology group.20 Case-control studies received a score between 0 and 6 (highest level of quality); we included in the meta-analysis studies that scored 5 or higher.w1 w3 w5 w9-w11 w21 Cohort studies received a score between 0 and 7 (highest level of quality); we included in the meta-analysis studies that scored 6 or higher.w4 (Details of quality assessment are on bmj.com.)

Included studies were independently reviewed by two authors (PYS and MC). Disparities were resolved by discussion.

Study characteristics

Each study was classified according to the design (observational or randomised controlled trial). We extracted relevant data on the characteristics of hormone replacement therapy (route of oestrogen administration, type of oestrogens, unopposed or opposed hormone regimen, duration of treatment) as well as the characteristics of venous thromboembolism (idiopathic or secondary, deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, ascertainment of venous thromboembolism) and used these to provide an overall estimate.

Statistical analysis

For each study we used the most adjusted relative risks or odds ratios, with their 95% confidence intervals. We analysed homogeneity between the studies using the χ2 and I2 statistics.21 22 The results of homogenous studies were pooled and an overall estimate of relative risk was obtained from a fixed effects model.23 Briefly, we calculated a weighted average of relative risks, with the weights being the inverse of variance of relative risk.24 For each study we estimated the variance of relative risk from the 95% confidence interval. When we detected heterogeneity between studies, we used a random effects model.23 Statistical analyses were done using SAS statistical software (version 9.1).

Results

Observational studies

Seven case-control studiesw1 w3 w5 w9-w11 w21 and one cohort studyw4 were eligible for inclusion and assessed for quality (fig 1 and tables 1-3 ). Table 4 summarises the characteristics of the included studies.

Fig 1 Results of literature search for randomised controlled trials and observational studies of hormone replacement therapy that reported venous thromboembolism

Table 1.

Quality assessment of included randomised controlled trials on hormone replacement therapy that reported venous thromboembolism

| Reference | Randomisation stated | Double blinding | Dropout and withdrawals | Generation of random numbers | Allocation concealment | Score (0-5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEPI 1995w12 | Yes | Yes | 3.0% dropout, 3.0% withdrawal | Computer generated block | Active drug and placebo in identical forms | 5 |

| HERS 1998w13 | Yes | Yes | 0% dropout, 2.1% withdrawal | Computer generated | Active drug and placebo in identical forms | 5 |

| EVTET 2000w14 | Yes | Yes | 23.6% dropout, 23.6% withdrawal | Computer generated block | Active drug and placebo in identical forms | 5 |

| ERA 2000w15 | Yes | Yes | 14.0% dropout, 4.0% withdrawal | Permuted block | Each woman received two tablets (active and placebo or two placebo) | 5 |

| WEST 2001w16 | Yes | Yes | 0% dropout, 1.4% withdrawal | Computer generated block | ? | 4 |

| ESPRIT 2002w17 | Yes | Yes | Not available | Computer generated block | Active drug and placebo in identical forms | 4 |

| WHI I 2002w18 | Yes | Yes | 3.5% dropout | Permuted block | Active drug and placebo in identical forms | 5 |

| WHI II 2004w19 | Yes | Yes | 2.2% dropout, 3.0% withdrawal | Permuted block | Active drug and placebo in identical forms | 5 |

| WISDOM 2007w20 | Yes | Yes | 0.01% dropout, 13.2% withdrawal | Computer generated block | Active drug and placebo in identical forms | 5 |

Appropriate=1; No information or not appropriate=0.

Table 2.

Quality assessment of included case-control studies on hormone replacement therapy that reported venous thromboembolism

| Reference | Appropriate inclusion and exclusion criteria* | First episode of venous thromboembolism | Objective diagnostic procedure | Adequate assessment of menopausal status | Accurate assessment of hormone replacement therapy† | Adequate analysis and adjustment | Score (0-6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boston CDSP 1974w21 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 5 |

| Daly 1996w1 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 5 |

| Jick 1996w3 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| Perez-Gutthann 1997w5 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 5 |

| Smith 2004w9 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| Douketis 2005w10 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| ESTHER 2007 w11 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6 |

Yes=1; no=0.

*Applied equally to cases and controls.

†Including route of oestrogen administration.

Table 3.

Quality assessment of included cohort studies on hormone replacement therapy that reported venous thromboembolism

| Reference | Appropriate method of participant selection | First episode of venous thromboembolism | Objective diagnostic procedure | Adequate assessment of menopausal status | Accurate assessment of hormone replacement therapy* | Overall low loss of follow-up | Adequate analysis and adjustment | Score (0-7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nurses’ health study 1996w4 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

Yes=1; n=0.

*Including route of oestrogen administration.

Table 4.

Characteristics of included observational studies on hormone replacement therapy that reported venous thromboembolism

| Reference | Route of oestrogen administration | Clinical end point | Oestrogen type | Definition for current users* | No of exposed cases | Adjusted risk ratio of venous thromboembolism (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boston CDSP 1974w21 | Oral | First episode of idiopathic venous thromboembolism | Mainly conjugated equine oestrogen | Not available | 3 | 1.9 (1.4 to 7.8) |

| Daly 1996w1 | Oral; transdermal | First episode of idiopathic venous thromboembolism | Estradiol (or estradiol valerate) or conjugated equine oestrogen; estradiol or estradiol valerate | <1 | 37; 5 | 4.6 (2.1 to 10.1); 2.0 (0.5 to 7.6) |

| Jick 1996w3 | Oral | First episode of idiopathic venous thromboembolism | Conjugated equine oestrogen or esterified oestrogen | <6 | 21 | 3.6 (1.6 to 7.8) |

| Nurses’ health study 1996w4 | Oral | First episode of pulmonary embolism | Mainly conjugated equine oestrogen | Not available | 68 | 2.1 (1.2 to 3.8) |

| Perez-Gutthann 1997w5 | Oral; transdermal | First episode of idiopathic venous thromboembolism | Estradiol (or estradiol valerate) or conjugated equine oestrogen; estradiol or estradiol valerate | <6 | 20; 7 | 2.1 (1.3 to 3.6); 2.1 (0.9 to 4.6) |

| Smith 2004w9 | Oral | First episode of venous thromboembolism | Conjugated equine oestrogen; esterified oestrogen | Not available | 121; 86 | 1.7 (1.2 to 2.2); 0.9 (0.7 to 1.2) |

| Douketis 2005w10 | Oral; transdermal | First episode of idiopathic venous thromboembolism | Not available; not available | <1 | 36; 3 | 1.9 (1.2 to 3.2); 0.8 (0.3 to 2.8) |

| ESTHER 2007w11 | Oral; transdermal | First episode of idiopathic venous thromboembolism | Estradiol (or estradiol valerate) or conjugated equine oestrogen; estradiol or estradiol valerate | <3 | 57; 67 | 4.5 (2.6 to 7.5); 1.1 (0.8 to 1.7) |

*Duration (months) between oestrogen use and venous thromboembolism.

All the studies investigated the risk of venous thromboembolism in relation to oral oestrogen usew1 w3-w5 w9-w11 w21 and four evaluated the risk of venous thromboembolism in relation to transdermal oestrogen use.w1 w5 w10 w11

Women were treated by 17-β-oestradiol,w1 w3 w5 w11 conjugated equine oestrogens,w1 w3-w5 w9 w11 w21 or esterified oestrogen.w3 w9 Women were generally classified as current users if they had used hormone replacement therapy at any time in the past one to six months before inclusion date.

In most of the studies the clinical end point was first time idiopathic venous thromboembolism—that is, without provoking risk factors25—either deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. One study restricted the end point to a first episode of idiopathic or non-idiopathic pulmonary embolismw4 whereas another study included first time idiopathic and non-idiopathic venous thromboembolism.w9 The clinical events were mostly validated by ultrasonography (deep vein thrombosis) or lung scanning (pulmonary embolism).

Randomised controlled trials

The postmenopausal estrogen/progestin interventions (PEPI) trialw12 was a multicentre, randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial that examined the effects of hormone replacement therapy on risk factors for heart disease among 875 healthy postmenopausal women (table 5). Intervention was placebo or conjugated equine oestrogens alone (0.625 mg/day) or combined with either cyclic medroxyprogesterone acetate, consecutive medroxyprogesterone acetate, or cyclic micronised progesterone. During three years of follow-up venous thromboembolism occurred in four women among pooled treated groups and in none among the placebo group.

Table 5.

Characteristics of included randomised controlled trials on hormone replacement therapy that reported venous thromboembolism

| Reference | No of participants* | Clinical background | Duration of trial (years) | No of events | Adjusted risk ratio for venous thromboembolism (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hormone replacement therapy group | Placebo group | |||||

| PEPI 1995w12 | 847 | “Healthy” | 3 | 4 | 0† | 1.9 (0.1 to 36.5)‡§ |

| HERS 1998w13 | 2763 | History of coronary heart disease | 4.1 | 34 | 12 | 2.9 (1.5 to 5.6) |

| EVTET 2000w14 | 140 | History of venous thromboembolism | 1.3 | 8 | 1 | 7.8 (1.0 to 60.5) |

| ERA 2000w15 | 309 | History of coronary heart disease | 3.2 | 7 | 1¶ | 3.6 (0.5 to 28.9)‡ |

| WEST 2001w16 | 664 | History of stroke | 2.8 | 3 | 4 | 0.8 (0.2 to 3.4) |

| ESPRIT 2002w17 | 1017 | History of coronary heart disease | 2 | 5 | 4 | 1.2 (0.3 to 4.6) |

| WHI I 2002w18 | 16608 | “Healthy” | 5.2 | 151 | 67 | 2.1 (1.6 to 2.7) |

| WHI II 2004w19 | 10739 | “Healthy” | 7 | 77 | 54 | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.8) |

| WISDOM 2007w20 | 5692 | Possible history of arterial disease | 0.99 | 22 | 3 | 7.4 (2.2 to 24.6) |

*About equal number in placebo and active treatment group except for two trials.w12 w15

†Hormone replacement therapy group n=682; placebo group n=165.

‡Risk calculated from data reported in study.

§To estimate risk ratio, number of events in placebo group was considered equal to 0.5.

¶Hormone replacement therapy group n=204; placebo group n=105.

The heart and estrogen/progestin replacement study (HERS)w13 was the first clinical trial designed to investigate the effect of hormone replacement therapy on recurrence of coronary heart disease. The study started in 1993 and was a multicentre randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial that enrolled 2763 postmenopausal women (mean age 66.7 years) with an intact uterus. Intervention was conjugated equine oestrogens (0.625 mg/day) plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (2.5 mg/day) or placebo. Venous thromboembolism was a secondary outcome, which occurred in 34 women in the hormone replacement therapy group and 12 in the placebo group.

The estrogen in venous thromboembolism trial (EVTET)w14 was a randomised double blind trial that compared 2 mg estradiol plus 1 mg norethisterone acetate per day with placebo in postmenopausal women with previously documented venous thromboembolism. The study was stopped prematurely after a mean follow-up of one year and four months. More women experienced recurrent venous thromboembolism in the hormone replacement therapy group than in the placebo group (8 v 1).

The estrogen replacement and atherosclerosis (ERA) trialw15 examined the effects of hormone replacement therapy on the progression of coronary atherosclerosis in 309 postmenopausal women who had angiographically verified coronary heart disease. The women were randomly assigned to receive conjugated equine oestrogens (0.625 mg/day) alone or conjugated equine oestrogens (0.625 mg/day) plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (2.5 mg/day), or placebo. During 3.2 years of follow-up, venous thromboembolism occurred in five women using conjugated equine oestrogens alone, two women using conjugated equine oestrogens plus medroxyprogestone acetate, and one woman using conjugated equine oestrogens plus placebo.

The women’s oestrogen for stroke trial (WEST)w16 was started in 1993 as a randomised, placebo controlled trial of hormone replacement therapy for the secondary prevention of cerebrovascular disease. This trial was carried out in 664 postmenopausal women (mean age 71 years) who had recently experienced an ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack. The women were randomly assigned to receive 1 mg of 17-β-oestradiol per day or placebo. Women were monitored for venous thromboembolism. Events occurred in three women in the hormone replacement therapy group and four in the placebo group.

The oestrogen in the prevention of reinfarction trial (ESPRIT)w17 was set up in the United Kingdom to assess the effect of unopposed estradiol valerate on the risk of coronary heart disease in postmenopausal women who had survived a first myocardial infarction. The study was a randomised, blinded, placebo controlled, secondary prevention trial among 1017 women aged 50-69 years. Women received estradiol valerate (2 mg/day) or placebo for two years. In this secondary prevention trial after a first myocardial infarction, two women in the hormone replacement therapy group and one in the placebo group experienced venous thromboembolism.

The women’s health initiative (WHI) focusesw18 w19 w26 w27 on strategies that could potentially reduce the incidence of coronary heart disease, breast and colorectal cancer, and fractures in postmenopausal women. Between 1993 and 1998 the initiative enrolled 161 809 postmenopausal women aged 50 to 79 years into a set of clinical trials (trials of low fat dietary pattern, calcium and vitamin D supplementation, and two trials of postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy) and an observational study at 40 clinical centres in the United States.

The oestrogen plus progestogen component of the women’s health initiative was a randomised controlled primary prevention trial in which 16 608 postmenopausal women with an intact uterus were randomly assigned to receive conjugated equine oestrogens (0.625 mg/day) plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (2.5 mg/day) or placebo.w18 Venous thromboembolism occurred in 151 women in the hormone replacement therapy group and 67 in the placebo group.

The oestrogen alone component of the women’s health initiative was a randomised controlled primary prevention trial in which 10 739 postmenopausal women with previous hysterectomy were randomly assigned to receive conjugated equine oestrogens (0.625 mg/day) or placebo.w19 Venous thromboembolism occurred in 167 women in the oestrogen group and 76 in the placebo group.

The women’s international study of long duration oestrogen after menopause (WISDOM) trialw20 was a randomised, double blinded, placebo controlled trial, set up in the UK, Australia, and New Zealand to assess the long term risk and benefits of hormone replacement therapy in women aged 50 to 69 without arterial disease within the past six months before inclusion (n=5692). The women were randomly assigned to receive conjugated equine oestrogens alone (0.625 mg/day) or conjugated equine oestrogens (0.625 mg/day) plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (2.5 mg/day) or placebo. The researchers planned to compare conjugated equine oestrogens plus medroxyprogesterone acetate with placebo, and conjugated equine oestrogens plus medroxyprogesterone acetate with conjugated equine oestrogens alone. Treatment was planned for 10 years but the study was prematurely closed because of the results from the women’s health initiative. After a mean follow-up of 11.9 months, venous thromboembolism occurred in 22 women in the conjugated equine oestrogens plus medroxyprogesterone acetate group and three in the placebo group. No significant differences were shown in outcomes when conjugated equine oestrogens plus medroxyprogesterone acetate were compared with conjugated equine oestrogens alone.

Results of the meta-analysis

The pooled risk of venous thromboembolism was assessed from eight observational studies and nine randomised controlled trials. From observational studies, the risk of venous thromboembolism was estimated by route of oestrogen administration. In addition, the risk of venous thromboembolism was estimated according to the characteristics of treatment (type, duration) and venous thromboembolism (idiopathic or secondary).

Risk of venous thromboembolism by characteristics of hormone replacement therapy

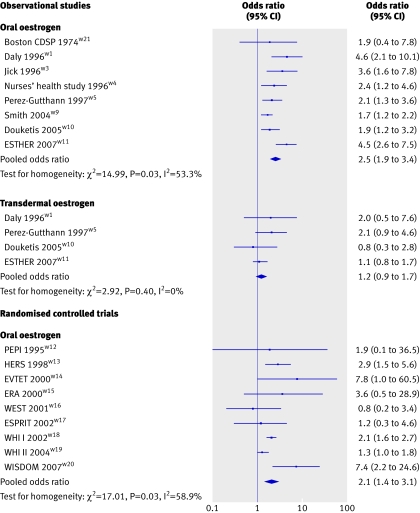

Figure 2 shows the pooled odds ratio of first time venous thromboembolism in relation to hormone replacement therapy use by study design and route of oestrogen administration. All but one of the observational studiesw21 consistently reported an association between oral oestrogen use and an increased risk of venous thromboembolism.w1 w3-w5 w9-w11 Four of the studies investigated the effect of transdermal oestrogen use on risk of a first episode of venous thromboembolismw1 w5 w10 w11: pooled odds ratio for oral oestrogen 2.5 (95% confidence interval 1.9 to 3.4) and for transdermal oestrogen 1.2 (0.9 to 1.7). The upper confidence limit for transdermal use (1.7) was lower than the lowest confidence limit for oral use (1.9). The association between venous thromboembolism and oral oestrogen use was confirmed by results from randomised controlled trials: pooled odds ratio 2.1 (1.4 to 3.1). The combined odds ratio from both trials and observational studies in oral oestrogen users was 2.4 (1.9 to 3.0) and was higher than the summary risk among women using transdermal oestrogen (P<0.001). No trials have investigated the effect of transdermal oestrogen on the risk of venous thromboembolism.

Fig 2 Risk of first episode of venous thromboembolism by study design and route of oestrogen administration

One study suggested that type of oestrogen might be an important determinant of the risk of venous thromboembolism.w9 In this study conjugated equine oestrogen was associated with increased risk whereas esterified oestrogen was not.

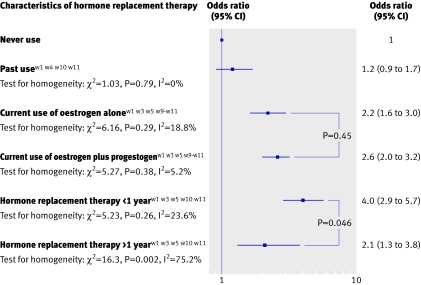

Data on the risk of venous thromboembolism in past users of hormone replacement therapy compared with never users were available in four observational studies.w1 w4 w10 w11 Data showed that previous use of hormone replacement therapy was not associated with an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (pooled odds ratio 1.2, 0.9 to 1.7; fig 3).

Fig 3 Risk of venous thromboembolism by characteristics of hormone replacement therapy among users of oral oestrogen

Six observational studies investigated the impact of unopposed and opposed oral oestrogen therapy on the risk of venous thromboembolism.w1 w3 w5 w9-w11 No significant difference in the risk of venous thromboembolism was observed between users of oral oestrogen alone (pooled odds ratio 2.2, 1.6 to 3.0) and oral oestrogen plus progestogen therapy (pooled odds ratio 2.6, 2.0 to 3.2).

Finally, the risk of venous thromboembolism has been assessed according to the duration of treatment. Information on duration of oral oestrogen use was available in only five case-control studies.w1 w3 w5 w10 w11 Results from these studies showed that the risk of venous thromboembolism was significantly higher for treatment within the first year (pooled odds ratio 4.0, 2.9 to 5.7) than for treatment of more than a year (pooled odds ratio 2.1, 1.3 to 3.8; P<0.05; fig 3).

Risk of venous thromboembolism by type of diagnosis

When analysis was restricted to the first episode of idiopathic events,w1 w3-w5 w10 w11 w21 the risk of venous thromboembolism in relation to oral oestrogen use substantially increased (pooled odds ratio 3.1, 2.3 to 4.1), whereas results for transdermal oestrogen use remained unchanged.

Analysis by type of venous thromboembolism showed no significant difference in risk between deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in relation to oral oestrogen use. From observational studies, the pooled odds ratio was 2.8 (1.9 to 4.0) for deep vein thrombosis and 2.7 (1.1 to 2.5) for pulmonary embolism. This result was confirmed by data from randomised controlled trials (data not shown).

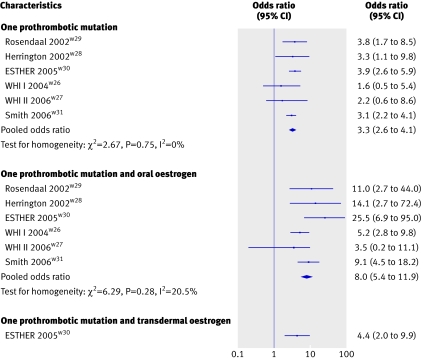

Women at high risk of venous thromboembolism

The effect of prothrombotic mutations26 27 on risk of venous thromboembolism, with or without hormone replacement therapy, was investigated in four case-control studiesw28-w31 and both clinical trials of the women’s health initiative.w26 w27 Overall, the presence of the factor V Leiden mutation or prothrombin G20210A mutation increased the risk of venous thromboembolism by more than threefold (pooled odds ratio 3.3, 2.6 to 4.1). The combination of thrombogenic mutations and oral oestrogen use, especially conjugated equine oestrogens with or without progestogen, further enhanced the risk of venous thromboembolism (odds ratio 8.0, 5.4 to 11.9) compared with women without mutations who did not use any treatment. In one study, however, no significant difference was observed in risk of venous thromboembolism between women with the factor V Leiden mutation or prothrombin G20210A mutation who used transdermal oestrogen and those with a mutation who did not use oestrogen (odds ratio 4.4, 2.0 to 9.9; fig 4).w30

Fig 4 Risks of venous thromboembolism among hormone replacement therapy users by route of oestrogen administration and presence of one of two prothrombotic mutations (factor V Leiden mutation or prothrombin G20210A mutation)

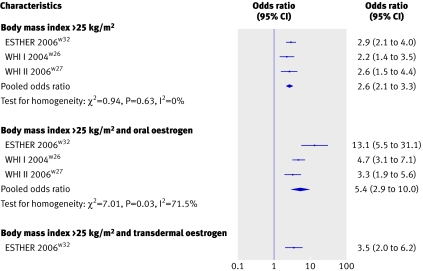

The association between venous thromboembolism and hormone replacement therapy with high body mass index was investigated in both clinical trials of the women’s health initiativew26 w27 and in one case-control study.w32 A high body mass index (overweight or obesity) increased the risk of venous thromboembolism (pooled odds ratio 2.6, 95% confidence interval 2.1 to 3.3). In addition, the combination of current oral oestrogen use and an increased body mass index resulted in a further increase in the risk of venous thromboembolism (pooled odds ratio 5.4, 2.9 to 10.0 compared with non-users with a body mass index less than 25kg/m²). In one study, however, current use of transdermal oestrogen did not confer an additional risk on women who were overweight or obese (fig 5).w32

Fig 5 Risks of venous thromboembolism among hormone replacement therapy users by route of oestrogen administration and presence of a high body mass index (overweight or obesity)

Discussion

This meta-analysis of observational studies and randomised controlled trials showed that current use of oral oestrogen increases the risk of venous thromboembolism by twofold to threefold. This increased risk was higher within the first year of treatment and more pronounced for women at higher risk of venous thromboembolism. Overall, with a baseline risk for venous thromboembolism of about 1 per 1000 woman years,28 29 an additional 1.5 events per 1000 women each year would be expected. Combined analysis of observational studies showed no significant increase in the risk of venous thromboembolism among women using transdermal oestrogen.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

Previous reviews and meta-analyses on hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism focused on oral oestrogen use and failed to take into account the route of oestrogen administration.7 11 13 15 This report provides a separate quantitative assessment of the thrombotic risk among users of oral and transdermal oestrogen. Moreover, the present meta-analysis investigated the impact of hormone replacement therapy by route of oestrogen administration among women at high risk of venous thromboembolism. In two previous reviews13 15 the risk of venous thromboembolism among oral oestrogen users with prothrombotic mutations was assessed from two case-control studies.w28 w29 We updated this meta-analysis by adding data from four other studies.w26 w27 w30 w31 Our meta-analysis shows a substantial increase in the risk of venous thromboembolism among oral oestrogen users with a high body mass index (overweight or obesity).w26 w27 w32

In the present meta-analysis, assessment of the risk of venous thromboembolism among users of transdermal oestrogen was based on relatively few data.w1 w5 w10 w11 The results should be interpreted with caution therefore and further investigation of transdermal oestrogen is needed. Another limitation of the present report is the lack of data on the impact of progestogens. Although this meta-analysis showed a similar risk of venous thromboembolism among users of oral oestrogen alone and opposed oral oestrogen, progestogens have recently emerged as a determinant of the risk of venous thromboembolism. One study reported that the risk of venous thromboembolism was higher in users of opposed oral oestrogen than in users of oral oestrogen alone,w10 and in the women’s health initiative the risk of venous thromboembolism was higher in the clinical trial of oestrogen and progestogenw18 than in the clinical trial of oestrogen alone.w19 In addition, among women recruited in the conjugated equine oestrogens plus medroxyprogesterone acetate versus conjugated equine oestrogens WISDOM trial, there was a suggestion of an increase in venous thromboembolism in the opposed oestrogen therapy group (relative risk 2.39, 95% confidence interval 0.62 to 9.24).w20 Finally, recent data from one case-control study showed that norpregnane derivatives might increase the risk of venous thromboembolism whereas there was no association between venous thromboembolism and micronised progesterone and pregnane derivatives.w11

Our meta-analysis of both observational studies and randomised controlled trials showed heterogeneity between studies among oral oestrogen users. An important source of heterogeneity between trials may arise from differences in duration of treatment. The WISDOM trial, which was closed after a median follow-up of 11.2 months, reported an odds ratio for venous thromboembolism higher than those from other randomised controlled trials.w20 When analysis was restricted to randomised trials with a longer follow-up, heterogeneity between studies disappeared. Explanations for heterogeneity between observational studies include differences in the type of venous thrombotic event. Two studies included women with non-idiopathic venous thromboembolism.w4 w9 If analysis was restricted to idiopathic venous thromboembolism, heterogeneity between observational studies disappeared. Differences were also found in results by study design. The association of venous thromboembolism with oral oestrogen use was lower in randomised controlled trials than in observational studies. This difference could be explained by inclusion of procedure related venous thromboembolism in the women’s health initiative trials as well as the high degree of non-adherence to study drugs in the randomised controlled trials, resulting in an underestimation of hormone effects in the randomised controlled trials.

Biological explanations for results

Biological evidence lends support to the difference in the risk of venous thromboembolism between users of oral oestrogen and users of transdermal oestrogen. Oral oestrogen administration results in a hepatic first pass effect and may impair the balance between procoagulant factors and antithrombotic mechanisms.30 Oral but not transdermal oestrogen increases plasma concentrations of prothrombin fragment 1+2,31 32 which is a marker for in vivo thrombin generation and increases the fibrinolytic potential in postmenopausal women. A lower antithrombin concentration has also been shown in women using oral oestrogen but not in those using transdermal oestrogens.33 In addition, an acquired resistance to activated protein C has been found in users of oral oestrogen,34 35 but two recent randomised trials indicated that these results did not apply to users of transdermal oestrogen.32 36 Thus transdermal oestrogen seems to have little or no effect on haemostasis.

Clinical implications

The findings of the present meta-analysis of studies by route of oestrogen administration may have important clinical implications. Pulmonary embolism accounts for about one third of the excess incidence of potentially fatal events associated with long term hormone replacement therapy.4 Therefore the risk of venous thromboembolism is an important determinant of the benefit and risk profile of hormone replacement therapy, and differences in the risk of venous thromboembolism between types of hormone replacement therapy may have important clinical implications. In addition, since recent guidelines recommend that women are prescribed the lowest effective dose of hormone replacement therapy for the shortest time possible,37 pulmonary embolism becomes a main adverse effect owing to oral oestrogen therapy within the first year of treatment. In contrast, there is little increase in the risk of stroke and breast cancer within the first year of treatment. Therefore reducing the risk of venous thromboembolism by using transdermal oestrogen could improve the benefit and risk profile of hormone replacement therapy, especially among women at high risk of venous thromboembolism—for example, women with known prothrombotic mutations or a high body mass index.

Future research

Future randomised trials of transdermal oestrogen compared with placebo will clarify this apparent safety with respect to thrombotic risk. Clinical research should continue into genetic factors influencing the risk associated with hormone replacement therapy, different oestrogen and progestogen formulations, different modes of delivery, lower dose options, and alternative regimens (for example, selective oestrogen receptor modulators, phytooestrogens). Such research will assist patients and clinicians in making treatment decisions on the basis of an individual’s benefits and risks.38

What is already known on this topic

Hormone replacement therapy improves the quality of life for women

The risk of venous thromboembolism is known to be increased with hormone replacement therapy

What this study adds

Transdermal oestrogen decreases the risk of venous thromboembolism compared with oral oestrogen and seems safe with respect to thrombotic risk

Women with prothrombotic mutations or a high body mass index should avoid oral oestrogens

Contributors: MC and PYS reviewed the studies and collected the data. MC, GPB, and PYS did the statistical analysis. MC, GPB, GDL, and PYS drafted the manuscript. MC, GBP, GDL, and PYS revised the paper. PYS is guarantor.

Funding: MC and PYS are funded by Inserm (Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Biomédicale), GPB is funded by Assistance Publique des Hôpitaux de Paris, and GDL is funded by the University of Glasgow.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Rymer J, Wilson R, Ballard K. Making decisions about hormone replacement therapy. BMJ 2003;326:322-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the women’s health initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;288:321-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, Bassford T, Beresford SA, Black H, et al. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the WOMEN’S HEALTH INITIATIVE randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004;291:1701-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beral V, Banks E, Reeves G. Evidence from randomised trials on the long-term effects of hormone replacement therapy. Lancet 2002;360:942-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lowe G. Update on the cardiovascular risks of hormone replacement therapy. Women’s Health 2007;3:87-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caine YG, Bauer KA, Barzegar S, ten Cate H, Sacks FM, Walsh BW, et al. Coagulation activation following estrogen administration to postmenopausal women. Thromb Haemost 1992;68:392-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller J, Chan BK, Nelson HD. Postmenopausal estrogen replacement and risk for venous thromboembolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2002;136:680-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oger E, Scarabin PY. Assessment of the risk for venous thromboembolism among users of hormone replacement therapy. Drugs Aging 1999;14:55-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canonico M, Straczek C, Oger E, Plu-Bureau G, Scarabin PY. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and cardiovascular disease: an overview of main findings. Maturitas 2006;54:372-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scarabin PY, Oger E, Plu-Bureau G. Differential association of oral and transdermal oestrogen-replacement therapy with venous thromboembolism risk. Lancet 2003;362:428-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson HD, Humphrey LL, Nygren P, Teutsch SM, Allan JD. Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy: scientific review. JAMA 2002;288:872-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosendaal FR, Van Hylckama Vlieg A, Tanis BC, Helmerhorst FM. Estrogens, progestogens and thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost 2003;1:1371-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomes MP, Deitcher SR. Risk of venous thromboembolic disease associated with hormonal contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy: a clinical review. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:1965-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lowe GD. Hormone replacement therapy and cardiovascular disease: increased risks of venous thromboembolism and stroke, and no protection from coronary heart disease. J Intern Med 2004;256:361-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu O, Robertson L, Langhorne P, Twaddle S, Lowe GD, Clark P, et al. Oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy, thrombophilias and risk of venous thromboembolism: a systematic review. The Thrombosis: Risk and Economic Assessment of Thrombophilia Screening (TREATS) Study. Thromb Haemost 2005;94:17-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu O. Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy and venous thromboembolism. Gend Med 2005;2(Suppl A):S18-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oger E, Plu-Bureau G, Scarabin P. Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy and cardiovascucular disease. In: Ian Greer, Jeff Ginsberg, Charles Forbes, eds. Women’s vascular health 2007:436-53.

- 18.Moher D, Pham B, Jones A, Cook DJ, Jadad AR, Moher M, et al. Does quality of reports of randomised trials affect estimates of intervention efficacy reported in meta-analyses? Lancet 1998;352:609-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, Olkin I, Rennie D, Stroup DF. Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. Quality of Reporting of Meta-analyses. Lancet 1999;354:1896-900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000;283:2008-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenland S. Quantitative methods in the review of epidemiologic literature. Epidemiol Rev 1987;9:1-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fleiss JL. The statistical basis of meta-analysis. Stat Methods Med Res 1993;2:121-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.White H, Murin S. Is the current classification of venous thromboembolism acceptable? No. J Thromb Haemost 2004;2:2262-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bertina RM. Genetic aspects of venous thrombosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2001;95:189-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Emmerich J, Rosendaal FR, Cattaneo M, Margaglione M, De Stefano V, Cumming T, et al. Combined effect of factor V Leiden and prothrombin 20210A on the risk of venous thromboembolism—pooled analysis of 8 case-control studies including 2310 cases and 3204 controls. Study Group for Pooled-Analysis in Venous Thromboembolism. Thromb Haemost 2001;86:809-16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oger E. Incidence of venous thromboembolism: a community-based study in western France. EPI-GETBP Study Group. Groupe d’Etude de la Thrombose de Bretagne Occidentale. Thromb Haemost 2000;83:657-60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cushman M, Kuller LH, Prentice R, Rodabough RJ, Psaty BM, Stafford RS, et al. Estrogen plus progestin and risk of venous thrombosis. JAMA 2004;292:1573-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lowe GD, Upton MN, Rumley A, McConnachie A, O’Reilly DS, Watt GC. Different effects of oral and transdermal hormone replacement therapies on factor IX, APC resistance, t-PA, PAI and C-reactive protein—a cross-sectional population survey. Thromb Haemost 2001;86:550-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scarabin PY, Alhenc-Gelas M, Plu-Bureau G, Taisne P, Agher R, Aiach M. Effects of oral and transdermal estrogen/progesterone regimens on blood coagulation and fibrinolysis in postmenopausal women. A randomized controlled trial. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1997;17:3071-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oger E, Alhenc-Gelas M, Lacut K, Blouch MT, Roudaut N, Kerlan V, et al. Differential effects of oral and transdermal estrogen/progesterone regimens on sensitivity to activated protein C among postmenopausal women: a randomized trial. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2003;23:1671-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conard J, Samama M, Basdevant A, Guy-Grand B, de Lignieres B. Differential AT III-response to oral and parenteral administration of 17 beta-estradiol. Thromb Haemost 1983;49:252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosing J, Middeldorp S, Curvers J, Christella M, Thomassen LG, Nicolaes GA, et al. Low-dose oral contraceptives and acquired resistance to activated protein C: a randomised cross-over study. Lancet 1999;354:2036-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoibraaten E, Mowinckel MC, de Ronde H, Bertina RM, Sandset PM. Hormone replacement therapy and acquired resistance to activated protein C: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Br J Haematol 2001;115:415-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Post MS, Christella M, Thomassen LG, van der Mooren MJ, van Baal WM, Rosing J, et al. Effect of oral and transdermal estrogen replacement therapy on hemostatic variables associated with venous thrombosis: a randomized, placebo-controlled study in postmenopausal women. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2003;23:1116-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Estrogen and progestogen use in peri- and postmenopausal women: March 2007 position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2007;14:168-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rexrode KM, Manson JE. Are some types of hormone therapy safer than others? Lessons from the estrogen and thromboembolism risk study. Circulation 2007;115:820-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]