Abstract

Steven J Thomas and colleagues think that recent changes in dental care provision have led to increased numbers of hospital admissions for dental abscess, and they suggest that access to routine and emergency dental care needs to be reviewed

Three complicated cases of dental abscess that presented in Bristol over a six month period in 2006 prompted us to investigate the frequency of admission for surgical treatment of dental abscess. Analysis of routine data on hospital admissions indicates that the number of admissions for surgical drainage of dental abscess has increased since the turn of the century.

Summary points

Dental sepsis is preventable

Dental sepsis can have serious local and systemic consequences

Dental abscess may present to both medical and dental practitioners

Hospital admissions for drainage of dental abscess have doubled in the past 10 years

Access to routine and emergency dental care needs to be reviewed

Three complicated cases of dental abscess

Case 1

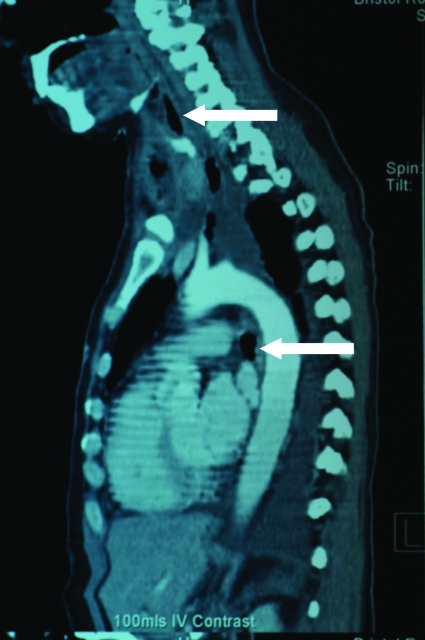

In March 2006, a 48 year old woman was referred by her general practitioner to the accident and emergency department with a submandibular swelling, which had been present for a week. She was diagnosed as having a right submandibular abscess secondary to a carious infected tooth. She was started on antibiotics and the abscess was drained. After two days she became increasingly unwell. She was tachypnoeic, hypotensive, and oliguric. Computed tomography showed that she had a fluid collection extending from the neck to the aortic arch (fig 1). She underwent a left thoracotomy and pus was drained from around the trachea and aortic arch. She was transferred to the critical care unit for ventilation and haemofiltration. Chest radiographs were consistent with a diagnosis of adult respiratory distress syndrome. Her lung and renal function improved gradually. She spent 22 days on the critical care unit and a further 22 days on the surgical ward. She was not registered with a dentist.

Fig 1 Case 1: parasagittal plane contrast enhanced computed tomography scan of the chest, showing gas and fluid extending from the level of the left cervical area (upper arrow) to the area of the aortic arch (lower arrow)

Case 2

In May 2006, a 48 year old man presented to the accident and emergency department with a left submandibular swelling. He was diagnosed as having a dental abscess. He was not registered with a dentist. He was advised to find a dentist and request treatment. He returned three days later to the same department after being unable to find a dentist. He was given antibiotics and was again advised to seek dental treatment. A day later, his partner found him in an unresponsive state. He was admitted to the critical care unit with a score of 9 on the Glasgow coma scale, a temperature of 32.5°C, a blood pH of 6.73, and blood pressure of 80/40 mm Hg. A diagnosis of diabetic ketoacidosis was made, with a dental abscess as the precipitant. The lower left first molar was removed and the neck abscess was drained. He was ventilated and dialysed. He left the critical care unit after three weeks.

Case 3

In July 2006, a 41 year old woman saw her general practitioner because of a left sided facial swelling. She was given a diagnosis of mumps. One week later she presented to the accident and emergency department with a necrotic left submandibular abscess secondary to an infected lower left first molar tooth (fig 2). The wound was treated by debridement, antibiotics, and vacuum drainage (fig 2). This patient was not registered with a dentist.

Fig 2 Case 3: appearance at presentation (top) and after debridement of the abscess (bottom)

These cases illustrate several points. Firstly, dental sepsis can have a range of local and systemic life threatening consequences. Secondly, cases of dental abscess may present to medical rather than dental practitioners in primary care and in accident and emergency departments. Thirdly, none of these cases was registered with a dentist.

Admissions for dental abscess

These three cases led us to examine routine information on hospital admissions for dental abscess. We wanted to see if the numbers of admissions for surgical treatment of dental abscess had changed in recent years.

We used hospital episode statistics data on all admissions to NHS hospitals in England. These data include information on private patients who were treated in NHS hospitals, patients who were resident outside England, and patients whose care was funded by the NHS but provided by treatment centres (including those in the independent sector). The records store information on up to 12 procedures for each episode (four before 2002-3) coded using the Office of Population Censuses and Surveys: Classification of Surgical Operations and Procedures, 4th Revision (OPCS4). The main operation is normally the most resource intensive procedure performed during the treatment episode.

We downloaded freely available data from the hospital episode statistics website (www.hesonline.nhs.uk). We examined trends in all NHS trusts in England for episodes where the main operation code was “drainage of abscess of alveolus of tooth” (OPCS4.2 code F16.1). Information was available for each year from 1998-9 to 2005-6 (1 April to 31 March).

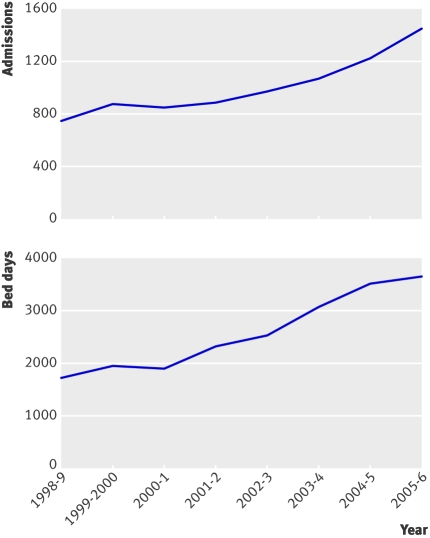

Figure 3 shows these data. The total number of admissions and bed days as a result of drainage of a dental abscess almost doubled between 1998-9 and 2005-6. For all time periods, the mean age of patients being treated for this condition was 32 years (except 2000-1 when it was 31 years) and the median length of hospital stay was about two days.

Fig 3 Total number of admissions and bed days for “drainage of abscess of alveolus of tooth” recorded by hospital episode statistics. Copyright 2008. Re-used with permission from the NHS Information Centre. All rights reserved

Comment

The number of cases of dental abscess requiring hospital admission in England has increased dramatically since the turn of the century. These national data are consistent with a recent audit carried out at the Hull Royal Infirmary, which showed an increase in the number of patients presenting to oral and maxillofacial surgery services with dental sepsis (from 17 to 25) between 1999 and 2004.1 A similar audit of services at Leeds General Infirmary, conducted between 2000 and 2005, showed no such increase.2 Both audits were based on small numbers of cases.

Because changes in the UK population are unlikely to explain the observed trends,this increase in numbers could reflect either a decline in oral health or changes in dental treatment. Surveys have reported improvements in the number of sound and untreated teeth in adults between 1978 and 1998.3 Furthermore, the mean number of decayed, missing, or filled teeth in children in the United Kingdom has declined, albeit modestly, in recent years.4 5 Although the number of people with no teeth has decreased in the UK,6 this is unlikely to explain our findings. This is because the mean age of people admitted for drainage of a dental abscess was around 32 years at all time periods, and both historical and projected changes in the proportion of dentate people within this age range were relatively small.6 Why then have admissions for surgical treatment of dental abscesses increased when the oral health of the population has apparently improved (potentially as a result of health behaviour, or better dental care, or both)?

Most serious dental infections are preventable with regular dental care. Indeed, this is the rationale for regular dental check ups. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence recommends that adults should have regular dental check ups every three to 24 months.7 Changes to dentists’ remuneration in the 1990s led many dentists to reduce their NHS workload. This was accompanied by a decline in the number of adults in England registered with an NHS dentist from 23 million in 1994 to around 17 million in 2003-4.8 Changes in service provision over the past 10 years could, therefore, have resulted in reduced provision of routine dental care and access to emergency dental care. These changes might explain the rise in surgical admissions for dental abscess. Our data cover only the past 10 years, and some of these changes in dental practice occurred before this time. We should therefore be cautious about drawing causal inferences from these trend data. An alternative explanation is that the problem lies with people not seeking dental care, rather than with the provision of care. However, a recent survey of 5212 members of the public and 750 dentists, conducted by the Commission for Patient and Public Involvement in Health,9 found that 22% of people had declined treatment because of high cost, and 84% of dentists felt that their new contract had failed to improve access to NHS services.

We believe that a doubling in a preventable condition that can have major consequences and even cause death constitutes a major public health problem that requires urgent action.10 11 We think that access to routine and emergency dental care needs to be reviewed. Furthermore, we believe that formal and robust systems of referral need to be established to ensure that medical practitioners can be confident that patients presenting to them with acute dental sepsis receive definitive dental treatment. These systems will undoubtedly vary as they will need to take account of local service provision and location.

We wish to acknowledge the role of Mark Yeatman (consultant cardiothoracic surgeon) and Graham Porter (consultant ear, nose, and throat surgeon) in the management of case 1.

Contributors and sources: SJT and CH had the idea for this paper. SJT, CH, and PJR wrote up the clinical details. CA obtained and analysed the hospital admission data. CA and ARN wrote the first draft. All authors contributed to revisions and all authors have seen and approved the final manuscript. SJT, CH, and PJR are surgeons and as such had noted several complicated cases of dental abscess that presented in Bristol over six months in 2006. These cases prompted us to investigate with ARN and CA the frequency of admission for surgical treatment of dental abscess using hospital episode statistics data. ST is guarantor.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent obtained.

References

- 1.Carter L, Starr D. Alarming increase in dental sepsis. Br Dent J 2006;200:243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morris G, Ong TK. Sepsis audit. Br Dent J 2006;200:601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Office for National Statistics. Adult dental health survey—oral health in the United Kingdom 1998 2000. London: Stationery Office.

- 4.Pitts NB, Boyles J, Nugent ZJ, Thomas N, Pine CM. The dental caries experience of 5-year-old children in Great Britain (2005/6). Surveys co-ordinated by the British Association for the Study of Community Dentistry. Community Dent Health 2007;24:59-63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pitts NB, Boyles J, Nugent ZJ, Thomas N, Pine CM. The dental caries experience of 11-year-old children in Great Britain. Surveys coordinated by the British Association for the Study of Community Dentistry in 2004/2005. Community Dent Health 2006;23:44-57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steele JG, Treasure E, Pitts NB, Morris J, Bradnock G. Total tooth loss in the United Kingdom in 1998 and implications for the future. Br Dent J 2000;189:598-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Dental recall—recall interval between routine dental examinations. Clinical guideline CG19. 2004. www.nice.org.uk/CG019

- 8.National Audit Office. Reforming NHS dentistry: ensuring effective management of risks 2004. www.nao.org.uk/publications/nao_reports/04-05/040525.pdf

- 9.National Commission for Patient and Public Involvement in Health. Dentistry watch report. 2007. http://147.29.80.160/portal/csc/genericContentGear/download/dentistry+watch+national+summary+of+re:+final3-15-10.pdf?document_id=116400639

- 10.Green AW, Flower EA, New NE. Mortality associated with odontogenic infection! Br Dent J 2001;190:529-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bulut M, Balci V, Akköse S, Armağan E. Fatal descending necrotising mediastinitis. Emerg Med J 2004;21:122-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]