Abstract

Maltose-binding protein (MBP) is a two-domain protein that undergoes a ligand-mediated conformational rearrangement from an “open” to a “closed” structure on binding to maltooligosaccharides. To characterize the energy landscape associated with this transition, we have generated five variants of MBP with mutations located in the hinge region of the molecule. Residual dipolar couplings, measured in the presence of a weak alignment medium, have been used to establish that the average structures of the mutant proteins are related to each other by domain rotation about an invariant axis, with the rotation angle varying from 5° to 28°. Additionally, the domain orientations observed in the wild-type apo and ligand-bound (maltose, maltotriose, etc.) structures are related through a rotation of 35° about the same axis. Remarkably, the free energy of unfolding, measured by equilibrium denaturation experiments and monitored by fluorescence spectroscopy, shows a linear correlation with the rotation angle, with the stability of the (apo)protein decreasing with domain closure by 212 ± 16 cal·mol–1 per degree of rotation. The apparent binding energy for maltose also shows a similar correlation with the interdomain angle, suggesting that the mutations, as they relate to binding, affect predominantly the ligand-free structure. The linearity of the energy change is interpreted in terms of an increase in the extent of hydrophobic surface that becomes solvent accessible on closure. The combination of structural, stability, and binding data allows separation of the energetics of domain reorientation from ligand binding. This work presents a near quantitative structure-energy-binding relationship for a series of mutants of MBP, illustrating the power of combined studies involving protein engineering and solution NMR spectroscopy.

Biological function depends critically on molecular dynamics. In multidomain proteins, such dynamics often manifest in hinge and shear motions that are intimately coupled to protein function in the cell (1). Motion is necessary for a large number of diverse processes, including ligand binding (2), cell regulation (3), metabolite transport (4), and enzyme catalysis (5). The bulk of our understanding of the conformational changes that occur in proteins comes from x-ray diffraction studies, although such experiments are, in general, confined to the elucidation of the initial (often open) and final (often closed) conformations, when both forms are accessible.

Recent developments in solution NMR spectroscopy promise to significantly impact the study of multidomain proteins. In particular, methodology for the measurement of anisotropic spin interactions in solution is now available (6, 7), and these interactions are sensitive reporters of orientation (7, 8). For example, residual dipolar couplings measured in the presence of weakly aligning media can be obtained and used to rapidly establish the average orientation of each domain in a protein and how such average orientations change in response to a perturbation, such as ligand binding. A particularly interesting system in this regard is maltose-binding protein (MBP), a 370-residue molecule belonging to the bacterial superfamily of periplasmic binding proteins. MBP is a two-domain protein, responsible for maltose uptake (9), that plays a major role in the signal transduction cascade that leads to chemotaxis (10). The two domains of the protein are of roughly equal size and are connected via a short helix and a two-stranded β-sheet (11). Previous work in our laboratory using dipolar coupling-based approaches with protein samples that are weakly aligned in a magnetic field has established that the structures of unligated, maltose-, maltotriose-, and maltotetraose-bound forms of MPB are very similar in solution and in the crystal (12). The unligated and ligand-bound conformations are related via a hinge rotation of 35°, with the bound structure in the closed form. Unexpectedly, however, the β-cyclodextrin-bound state in solution is ≈10° more closed than what is observed in the x-ray structure (8). This difference has been confirmed from a calculation of the diffusion tensors of each domain from 15N spin relaxation data recorded on an unaligned sample (13), establishing that the changes observed in solution are not the result of protein interactions with alignment media. Differences between solution and crystal conformations highlight the need for methods distinct from x-ray crystallography for the study of multidomain proteins.

Structural studies of MBP have been supplemented by mutagenesis experiments in which residues that are important for stabilizing the conformation of the protein are identified. For example, Marvin and Hellinga (14) have devised an elegant set of hinge mutations that show increased affinity for maltose and suggest that changes in binding arise due to differences in domain orientations that are caused by the mutations. Here we use residual dipolar couplings to rapidly establish the solution conformations of a number of these mutants and show that each of the mutants is related to the open structure of the protein through rotation of one of the domains about an invariant hinge axis. The open and closed structures can in turn also be related via rotation about this hinge. Thus, the mutants provide “snap-shots” of the structure of the protein as it traverses from open to closed conformations. By combining stability data on each mutant along with an accurate measure of the interdomain angle, the energy profile of the apoprotein along the trajectory that transforms the open conformation to the closed can be mapped. Remarkably, mutant stability and ligand affinity correlate in a linear manner with the extent of domain closure.

Materials and Methods

MBP Mutagenesis, Expression, and Purification. Single amino acid substitutions were generated from the vector pmal-c0 by using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). All mutants were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells in 99.9% D2O, M9 media containing 0.1% 15NH4Cl, and 0.3% 1H,13C-glucose as the sole sources of nitrogen and carbon, respectively. MBP was purified from cell lysates as described (15), followed by partial unfolding in 2.5 M guanidinium hydrochloride to back-exchange protons at labile sites and to ensure the absence of ligand bound to the protein. Refolding was achieved by fast dilution into guanidine–HCl free buffer. The following mutants of MBP were constructed: I329C (45 mg/liter), I329C*, I329F (22 mg/liter), I329W (17 mg/liter), and I329W/A96W (20 mg/liter), with the amounts of pure protein from 1 liter of growth media indicated. I329C* was prepared from purified I329C by addition of the thiol-reactive compound N-((2-(iodoacetoxy)ethyl)-N-methyl)amino-7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazole (Molecular Probes, product reference I-9) at a 15:1 molar ratio. Incubation for 8 h at room temperature and subsequent purification by gel filtration produced the nonnatural side-chain adduct.

NMR Experiments and Data Analysis. All NMR samples were between 0.8 mM and 1.2 mM in protein, 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2), 2 mM NaN3, and 8% D2O. All experiments were recorded at 37°C on a 500-MHz Varian Inova spectrometer. Backbone assignments of the mutants were obtained by comparing wild-type chemical shifts to those obtained from a 3D TROSY-HNCO experiment (16). Alignment of the protein was achieved with Pf1 phage (17) at concentrations between 10 and 14 mg/ml leading to residual 2H water splitting of 11–14 Hz. 1H-15N dipolar couplings (1DHN) were measured by using a regular TROSY-HNCO and a J-scaled TROSY-HNCO with α = 1 (18), recorded in an interleaved manner. Spectra were processed with nmrpipe/nmrdraw software (19) and analyzed by using either pipp/capp (20) or nmrview (21) in conjunction with auxiliary tcl/tk scripts written in-house.

Dipolar couplings were used to determine the interdomain orientation of each mutant MBP following the procedure described in Evenas et al. (12). The solution conformation of each mutant was generated starting from x-ray structures of the open form, 1OMP, 1JW4 (22, 23); the maltose-bound form, 1ANF, 1JW5 (22, 24); the maltotriose/maltotriotol-bound forms, 3MBP, 1FQB, 1FQC (24, 25); the maltotetraose/maltotetraotol-bound forms, 4MBP, 1EZ9 (two molecules in the asymmetric unit), 1FQD (22, 24, 25); and the β-cyclodextrin-bound form, 1EZO (26). An algorithm implemented within the cns software package (27) used the experimental set of dipolar couplings measured for each mutant as the unique set of experimental restraints to reorient the domains (8). Dipolar couplings belonging to residues with high B-factor values (1–5, 25–34, 41, 50–55, 80–84, 100, 101, 171–175, 185, 352–354, 369, and 370) were excluded from the analysis so that a total of 181, 154, 141, 174, and 171 1DHN values were used for the I329C, I329C*, I329F, I329W, and I329W/A96W mutants, respectively. For each structure, synthetic intradomain restraints were generated to ensure that the intradomain structures were not changed during the course of the minimization procedure. The restraints involve N-N and HN-HN distances separated by <15 Å and backbone dihedral angles ψ and ϕ and were enforced with parabolic potentials with very narrow flat regions (±0.01 Å and ±0.1° for distance and angle restraints; see ref. 12 for details).

For each mutant, 12 solution conformations were calculated for each of the 12 starting structures. It is convenient to describe the relative orientation of domains in a given structure in terms of a series of rotations that transforms the ligand-free structure, 1OMP (reference structure below) to the structure in question. Briefly, the C-terminal domains of the reference and query structure (one of the mutants, for example) are aligned, and the transformation from the N domain of the reference to the N domain of the query molecule is calculated. The Euler angles describing the transformation are recast in terms of three rotations about axes referred to as closure, twist, and bend (in that order). The bend axis connects the centers of mass of the two domains in the 1OMP structure, the closure axis is derived from the hinge axis that transforms the 1OMP (open) structure to the 1ANF (closed) structure (the component perpendicular to the bend axis), and the twist axis is orthogonal to the first two. A detailed description is given elsewhere (8, 12).

Fluorescence Experiments. All of the experiments were collected by using an Aviv (Aviv Associates, Lakewood, NJ) ATF 105 spectrofluorometer with λex = 280 nm, λem = 350 nm. Up to six independent measurements of binding affinity per mutant were obtained by combining three different protein concentrations (50, 75, and 100 nM) with two different saturation concentrations of ligand (protein/ligand ratios of 1:10 and 1:15). The dissociation constant Kd can be extracted from the global fitting of all measurements made for each mutant by using the relation between fluorescence intensity and Kd given in Maxwell and Davidson (28). Uncertainties in the extracted binding constants were obtained from a comparison of Kd values generated from independent fits of each measurement.

The stability of each mutant protein at 37°C, defined as the free energy of unfolding (ΔGU-F), was established by equilibrium denaturation experiments using guanidinium hydrochloride and monitored by fluorescence spectroscopy (λex = 280 nm, λem = 350 nm). Experiments were carried out in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2), except for the I329C mutant in which 500 μM β-mercaptoethanol was added to prevent dimerization in the unfolded state. Data for each mutant were fit to a two-state unfolding model to yield ΔGU-F values; errors were obtained from duplicate measurements.

Results and Discussion

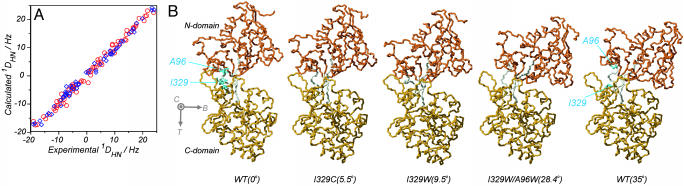

Monitoring Domain Closure at High Resolution. We have used residual dipolar couplings in concert with x-ray-derived starting structures of both unligated and ligand-bound wild-type MBP to rapidly establish the relative orientation of domains in a series of MBP mutants, including I329C, I329F, I329W, I329W/A96W, and I329C*. 1HN, 15N, and 13CO assignments (I329C, 84%; I329F, 87%; I329W, 86%; I329W/A96W, 89%; and I329C*, 85%) of each mutant were obtained by making use of the high degree of similarity between chemical shifts of the mutants and the wild type. For each mutant (no ligand present), a set of dipolar couplings from N and C domains has been used to reorient starting crystal structures following the protocol outlined in Materials and Methods and described in detail in a series of publications (8, 12, 29). Fig. 1 shows an example of the correlation between experimentally derived dipolar couplings for the I329W mutant along with those that are predicted from the 1OMP “daughter” structure, formed by rotating the domains of the 1OMP x-ray structure to match the experimental couplings. It is clear that excellent agreement is obtained.

Fig. 1.

Structural changes associated with domain reorientation in MBP. (A) Correlation between experimental 1DHN values recorded on I329W and those predicted on the basis of the 1OMP starting x-ray structure, rotated first to best satisfy the experimental dipolar coupling values. Dipolar couplings from the N- and C-terminal domains are shown in blue and red, respectively. (B Left to Right) Wild-type open structure (0° closure), I329C (5.5° closure), I329W (9.5° closure), I329W/A96W (28.4° closure), and the closed conformation for wild type in the absence of ligand (35° closure). The open wild-type structures are identical in solution and in the crystal, as are the closed wild-type structures (12, 36). The closure, bend, and twist (C, B, T) coordinate axes are displayed. The residues that have been mutated are shown in blue.

Also shown in Fig. 1 are the average solution conformations for three of the mutants along with the closure angles (see below), with the structures of wild-type MBP in the open and closed states added for clarity. The closure, twist, bend coordinate system (see Materials and Methods) is also displayed in Fig. 1. The structures are related through rotations almost exclusively about the closure axis, with closure angles of 5.5° ± 0.9°, 9.5° ± 0.9°, 10.4° ± 0.9°, 21.0° ± 1.0°, and 28.4° ± 1.8° for I329C, I329W, I329F, I329C*, and I329W/A96W, respectively. (The ± values are calculated as 1 SD from the mean of values obtained from the 12 different starting x-ray structures). Rotations about bend and twist axes are very small, with values ranging from –0.1° to 2.6° for bend and from –0.6° to 0.1° for twist, respectively. Notably, there is essentially no translational component associated with each conformational change, with net translation of one domain with respect to the other <0.3 Å in any of the proteins studied (calculated as described in Goto et al., ref. 29; see Materials and Methods of ref. 29). The x-ray-derived structures of MBP in open and closed conformations also indicate that little translation is involved (<0.25 Å) in the interconversion between conformers. Finally, it is important to emphasize that the maximum closure angle of MBP observed in both x-ray (23) and solution (12) studies is 35°, and that this value is for the bound state of the protein. Thus, the mutants studied here span almost the full range of possible values for the closure angle, so that the series of proteins examined map out the trajectory from open to closed states of the protein.

Correlation Between Stability and Domain Orientation. ΔGU-F values have been extracted from equilibrium denaturation experiments with guanidinium hydrochloride by using a two-state unfolding model. Previous calorimetric studies have established the validity of this model for MBP under the pH conditions (pH 7.2) used in the present study (30). The correlation between experimental ΔGU-F values and closure angles obtained for each mutant is shown in Fig. 2A, and there is a clear tendency for the protein to become less stable on closure. A sizeable fraction of the change in stability can derive from the mutation itself, that is, substitutions of amino acids alter the solvation energy of the protein in both folded and the unfolded states. This contribution to global stability can be estimated from the free energy of transfer of amino acids from an organic solvent to water (ΔGtransfer) (31), by using tabulated values for ΔGtransfer (32). For N-((2-(iodoacetoxy)ethyl)-N-methyl)amino-7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazole (I329C*), ΔGtransfer has been calculated from the nonpolar surface area of the functionalized side-chain (25 cal/Å2 for aliphatic atoms and 16 cal/Å2 for the aromatic group). Experimental ΔGU-F values have been corrected by using the relation:

|

[1] |

where χU (set to 1) and χF correspond to the fraction of solvent accessible surface areas at the sites of mutation in the unfolded and folded states, respectively,  and

and  are the tabulated transfer free energy values for the side-chains in the WT and mutant structures (for example, in I329W, WTaa = I, and Maa = W), and the sum runs over all mutated sites in the protein.

are the tabulated transfer free energy values for the side-chains in the WT and mutant structures (for example, in I329W, WTaa = I, and Maa = W), and the sum runs over all mutated sites in the protein.  thus gives the stability for a wild-type sequence that adopts the same interdomain conformation displayed by the mutant, and in what follows, all reference to stability will be to this value and not the experimentally derived uncorrected free energy term. Although the exact orientations of the mutated side-chains in the folded state are not known, modeling studies have shown that the fraction of accessible surface area at the site of mutation changes very little (<2.5%) from the wild-type protein. The solvent accessibilities of I329 and A96 in the open (closed) forms of MBP are 8.1% (20.7%) and 0.9% (2.9%), respectively, indicating that changes in accessibility at these positions depend only weakly on closure angle, and that the bulk of the solvation free energy effects are due to the unfolded state.

thus gives the stability for a wild-type sequence that adopts the same interdomain conformation displayed by the mutant, and in what follows, all reference to stability will be to this value and not the experimentally derived uncorrected free energy term. Although the exact orientations of the mutated side-chains in the folded state are not known, modeling studies have shown that the fraction of accessible surface area at the site of mutation changes very little (<2.5%) from the wild-type protein. The solvent accessibilities of I329 and A96 in the open (closed) forms of MBP are 8.1% (20.7%) and 0.9% (2.9%), respectively, indicating that changes in accessibility at these positions depend only weakly on closure angle, and that the bulk of the solvation free energy effects are due to the unfolded state.

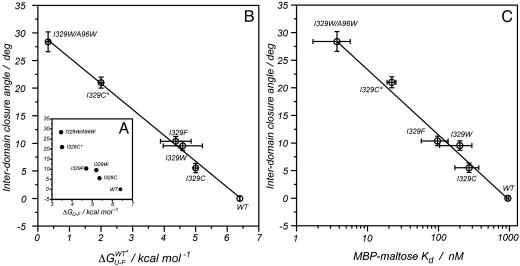

Fig. 2.

The interdomain closure angle correlates with both the free energy of unfolding and the affinity for maltose. (A) Experimental values for the free energy of unfolding (ΔGU-F). (B) Values in A corrected for the changes in stability introduced with the mutation ( ); a linear dependence arises with a slope of 212 ± 16 cal·mol–1 per degree of rotation. (C) Correlation between the dissociation constant for maltose-binding and closure angle (slope = 151 ± 38 cal·mol–1·deg–1). Contributions arising from differences between the wild-type and mutant residues have been corrected, following a procedure analogous to that described for obtaining the correlation in B.

); a linear dependence arises with a slope of 212 ± 16 cal·mol–1 per degree of rotation. (C) Correlation between the dissociation constant for maltose-binding and closure angle (slope = 151 ± 38 cal·mol–1·deg–1). Contributions arising from differences between the wild-type and mutant residues have been corrected, following a procedure analogous to that described for obtaining the correlation in B.

Values of  vs. domain closure for the different mutants examined are plotted in Fig. 2B, and remarkably a linear correlation is observed (r value of 0.99). The stability of the protein decreases by 212 ± 16 cal·mol–1 per degree of closure, so that at room temperature, fluctuations in domain closure of 2° to 3° are expected. In principle, a linear dependence of

vs. domain closure for the different mutants examined are plotted in Fig. 2B, and remarkably a linear correlation is observed (r value of 0.99). The stability of the protein decreases by 212 ± 16 cal·mol–1 per degree of closure, so that at room temperature, fluctuations in domain closure of 2° to 3° are expected. In principle, a linear dependence of  on any structural parameter is unexpected, because global changes in free energy often correspond to the mutual cancellation of multiple local contributions (see below). Of note, for large closure angles (approaching the closed conformation),

on any structural parameter is unexpected, because global changes in free energy often correspond to the mutual cancellation of multiple local contributions (see below). Of note, for large closure angles (approaching the closed conformation),  values are close to zero. For example, a “hypothetical” wild-type protein with a closure angle of 28° (observed for the I329W/A96W double mutant) would have a stability of only 0.5 kcal·mol–1. Although extrapolations to regions outside the limits of the experimental data must be viewed with caution, Fig. 2B suggests that the closed conformation of the protein (wild-type sequence, closure angle of 35°) would not be stable in the absence of ligand under physiological conditions (pH 7.2, 37°C).

values are close to zero. For example, a “hypothetical” wild-type protein with a closure angle of 28° (observed for the I329W/A96W double mutant) would have a stability of only 0.5 kcal·mol–1. Although extrapolations to regions outside the limits of the experimental data must be viewed with caution, Fig. 2B suggests that the closed conformation of the protein (wild-type sequence, closure angle of 35°) would not be stable in the absence of ligand under physiological conditions (pH 7.2, 37°C).

On the basis of the available dipolar coupling data, it is not possible to distinguish between the scenario where each mutant has a unique static structure and the case where each mutant corresponds to an ensemble of rapidly interconverting open and closed structures, where the relative populations of each change in response to mutation (8). The “effective” domain orientation obtained from the dipolar analysis will be the same in both situations, and this average orientation is well defined by the data, as discussed in detail previously (8). The linear relation between closure angle and  in Fig. 2B argues strongly against the second scenario, however, because a simple two-state interconverting model predicts a logarithmic dependence, as well as a difference of ≈2.5 kcal·mol–1 between open and closed states (an extrapolated value of 7.4 kcal·mol–1 is obtained) (see Fig. 3 below).

in Fig. 2B argues strongly against the second scenario, however, because a simple two-state interconverting model predicts a logarithmic dependence, as well as a difference of ≈2.5 kcal·mol–1 between open and closed states (an extrapolated value of 7.4 kcal·mol–1 is obtained) (see Fig. 3 below).

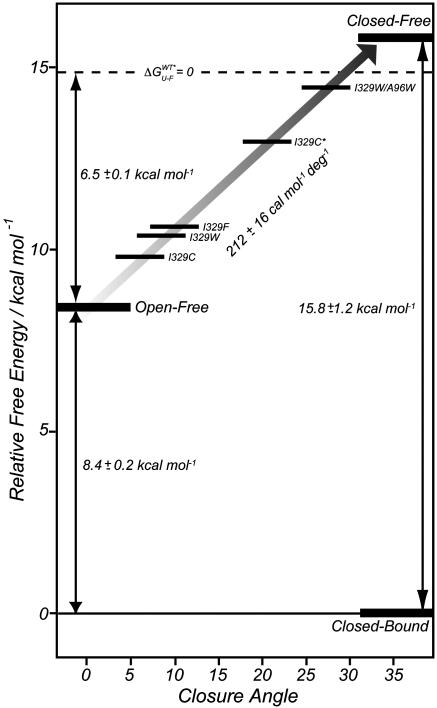

Fig. 3.

Energy level diagram showing the relative stabilities of the apo wild-type open, apo wild-type closed, and mutant apo conformations of MBP along with the wild-type closed bound form of the protein. The dashed axis indicates the point at which the unfolded apo state is as stable as the folded. For all mutants, the energy has been corrected according to Eq. 1 so that the stabilities plotted are those associated with the wild-type sequence with the closure angle indicated along the x axis. The closed-bound state is arbitrarily assigned a free energy value of 0.

Ligand-Binding Energies. To complement the stability measurements, binding constants of MBP for maltose were determined by fluorescence spectroscopy at 37°C. Measured values (before correction for differential solvation effects of mutant and wild-type residues, see legend to Fig. 2) range from 900 nM for wild type to 6.7 nM for the double mutant, I329W/A96W, indicating that the interaction between MBP and the sugar is also linked to changes in the closure angle. Fig. 2C shows the correlation between affinity and closure angle for the variants of MBP studied. A linear correlation is again obtained, with an increase in binding energy of 151 ± 38 cal·mol–1 per degree of closure, close to the change in protein stability with closure, 212 ± 16 cal·mol–1·deg–1. The similarity of the slopes suggests that the mutations likely affect the ligand-free folded state of the protein predominantly (vs. the unfolded state), with the small differences reflecting perhaps subtle changes in the structures of the ligand-bound states of the different mutants. The linear correlation also strongly supports changes in binding between the different mutants reflecting differences in average domain orientation, rather than significant differential perturbations in the binding site. This is especially likely to be the case because the mutations are far removed from where sugar binds (14). Preliminary binding studies of the mutants with ligands other than maltose show similar increases in ligand affinity relative to wild-type protein (data not shown).

Energetics of Interdomain Closure. The NMR and fluorescence measurements described above present a self-consistent picture of how the mutations affect the structure, stability, and binding properties of the protein. Moreover, the data are sufficiently comprehensive that a separation of the energetics of domain rearrangement from ligand binding is possible. Fig. 3 shows the relative free energies of the different conformations of MBP vs. closure angle, along with the relative position of the maltose-bound conformation (Closed-Bound). In constructing this diagram, we have used a value for the energetic cost of domain reorientation of 212 cal·mol–1·deg–1, estimated from the stability measurements (Fig. 2B). Remarkably, the equilibrium denaturation experiments, in conjunction with NMR structural data, predict that for closure angles greater than ≈30° the wild-type protein unfolds (dashed line in Fig. 3). Extrapolation of our data to a closure angle of 35°, corresponding to the completely closed conformation seen in ligand-bound forms of the protein, predicts a change in free energy of ≈16 kcal·mol–1 between closed-free and closed-bound states.

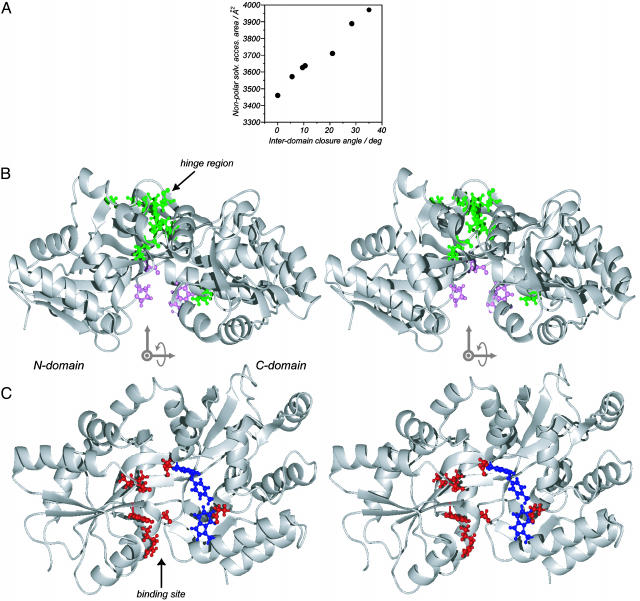

What is the origin of the loss in stability ( ) between open-free and closed-free states of the protein, and why is the stability change linear with closure angle? Clearly there are many factors that could be involved, but Fig. 4A provides a clue. The nonpolar solvent accessible surface area of MBP increases with interdomain closure, and this change can at least qualitatively account for the magnitude of the stability change observed. If, as we suggest, exposure of hydrophobic side-chains does in fact play a major role in the stability changes observed with the mutations, then the linear relation of Fig. 4A would lead to the observed linear change in energy with closure (Fig. 2) and hence the constant force that must be applied to reorient the domains. Fig. 4B highlights the hydrophobic side-chains that become more exposed as the closure angle increases in green, whereas those with increased burial are indicated in pink.

) between open-free and closed-free states of the protein, and why is the stability change linear with closure angle? Clearly there are many factors that could be involved, but Fig. 4A provides a clue. The nonpolar solvent accessible surface area of MBP increases with interdomain closure, and this change can at least qualitatively account for the magnitude of the stability change observed. If, as we suggest, exposure of hydrophobic side-chains does in fact play a major role in the stability changes observed with the mutations, then the linear relation of Fig. 4A would lead to the observed linear change in energy with closure (Fig. 2) and hence the constant force that must be applied to reorient the domains. Fig. 4B highlights the hydrophobic side-chains that become more exposed as the closure angle increases in green, whereas those with increased burial are indicated in pink.

Fig. 4.

(A) Nonpolar solvent accessible surface area, as estimated by rolling a ball of radius 1.4 Å along the protein surface (37), as a function of interdomain closure angle. (B) Hydrophobic residues with increased (decreased) solved accessibility on domain closure are shown in green (pink). Only those residues with a change >10 Å2 between open and closed conformers are displayed. There is a net destabilization of the protein on closure from this effect. (C) Residues that form van der Waals interactions with maltose in the bound form are shown in blue, whereas those hydrogen bonding to sugar are in red. The orientations of the protein are different in B and C, with the axis system showing how the view in B is transformed to that in C indicated. In B and C, the structures are drawn in stereo.

The large  between open- and closed-free states of MBP is also likely a reflection of the way that polar and hydrophobic groups are distributed in the binding site of the protein, Fig. 4C. The N domain contributes many of the polar moieties (red) that hydrogen bond with the sugar in the bound state, whereas the C domain is responsible for many of the protein–sugar stacking interactions. This arrangement is in contrast to that found in the homologous glucose/galactose-binding protein (GGBP) where hydrogen bonds involving residues from both domains immobilize the ligand (33). The crystal structure of GGBP in the closed ligand-free conformation shows that hydrogen bonds with water molecules mediate the interactions between residues of the two domains (34), providing the stabilization that is absent in the closed apo MBP conformation due to the lack of surface complimentarily in this case. For MBP, a ligand is, therefore, required to bridge the two domains.

between open- and closed-free states of MBP is also likely a reflection of the way that polar and hydrophobic groups are distributed in the binding site of the protein, Fig. 4C. The N domain contributes many of the polar moieties (red) that hydrogen bond with the sugar in the bound state, whereas the C domain is responsible for many of the protein–sugar stacking interactions. This arrangement is in contrast to that found in the homologous glucose/galactose-binding protein (GGBP) where hydrogen bonds involving residues from both domains immobilize the ligand (33). The crystal structure of GGBP in the closed ligand-free conformation shows that hydrogen bonds with water molecules mediate the interactions between residues of the two domains (34), providing the stabilization that is absent in the closed apo MBP conformation due to the lack of surface complimentarily in this case. For MBP, a ligand is, therefore, required to bridge the two domains.

In summary, we have presented a study of protein stability as a function of domain orientation in MBP along a pathway extending from the open to the closed conformation of the molecule. Mutations have been used to generate a series of proteins with differing interdomain structures, studied via residual dipolar couplings. Remarkably, a linear correlation between stability and the extent of domain closure has been obtained. The experiments described here are somewhat analogous to those in atomic force microscopy and laser tweezer studies, where the force required to pull or translate a part of the protein with respect to the rest is measured (35). Here it is the energy associated with the rotation of one protein component with respect to another that has been quantified. The combination of site-directed mutagenesis and dipolar couplings to rapidly assess structural changes promises to be a powerful approach for the study of structure–stability relationships in multidomain proteins.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Vitali Tugarinov (University of Toronto) for providing the scripts for data analysis, Dr. Alan Davidson (University of Toronto) for use of the spectrofluorometer, and Drs. Julie Forman-Kay and Anthony Mittermaier for many helpful discussions. O.M. is a recipient of a European Molecular Biology Organization postdoctoral fellowship. L.E.K. holds a Canada Research Chair in Biochemistry.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviation: MBP, maltose-binding protein.

See commentary on page 12529.

References

- 1.Gerstein, M., Lesk, A. M. & Chothia, C. (1994) Biochemistry 33 6739–6749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawson, C. L., Zhang, R., Schevitz, R. W., Otwinowski, Z., Joachimiak, A. & Sigler, P. B. (1988) Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 3 18–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ikura, M., Clore, G. M., Gronenborn, A. M., Zhu, G., Klee, C. B. & Bax, A. (1992) Science 256 632–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oh, B. H., Pandit, J., Kang, C. H., Nikaido, K., Gokcen, S., Ames, G. F.-L. & Kim, S. H. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268 11348–11355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stillman, T. J., Baker, B. J., Britton, K. L. & Rice, D. W. (1993) J. Mol. Biol. 234 1131–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tjandra, N. & Bax, A. (1997) Science 278 1111–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tolman, J. R., Flanagan, J. M., Kennedy, M. A. & Prestegard, J. H. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92 9279–9283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skrynnikov, N. R., Goto, N. K., Yang, D., Choy, W. Y., Tolman, J. R., Mueller, G. A. & Kay, L. E. (2000) J. Mol. Biol. 295 1265–1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boos, W. & Shuman, H. (1998) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62 204–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mowbray, S. L. & Sandgren, M. O. J. (1998) J. Struct. Biol. 124 257–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spurlino, J. C., Lu, G. Y. & Quiocho, F. A. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266 5202–5219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evenas, J., Tugarinov, V., Skrynnikov, N. R., Goto, N. K., Muhandiram, R. & Kay, L. E. (2001) J. Mol. Biol. 309 961–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hwang, P. M., Skrynnikov, N. R. & Kay, L. E. (2001) J. Biomol. NMR 20 83–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marvin, J. S. & Hellinga, H. W. (2001) Nat. Struct. Biol. 8 795–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gardner, K. H., Zhang, X., Gehring, K. & Kay, L. E. (1998) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120 11738–11748. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang, D. & Kay, L. E. (1999) J. Biomol. NMR 13 3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hansen, M. R., Mueller, L. & Pardi, A. (1998) Nat. Struct. Biol. 5 1065–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kontaxis, G., Clore, G. M. & Bax, A. (2000) J. Magn. Reson. 143 184–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delaglio, F., Grzesiek, S., Vuister, G. W., Zhu, G., Pfeifer, J. & Bax, A. (1995) J. Biomol. NMR 6 277–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garrett, D. S., Powers, R., Gronenborn, A. M. & Clore, G. M. (1991) J. Magn. Reson. 95 214–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson, B. A. & Blevins, R. A. (1994) J. Biomol. NMR 4 603–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duan, X. Q. & Quiocho, F. A. (2002) Biochemistry 41 706–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharff, A. J., Rodseth, L. E., Spurlino, J. C. & Quiocho, F. A. (1992) Biochemistry 31 10657–10663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duan, X., Hall, J. A., Nikaido, H. & Quiocho, F. A. (2001) J. Mol. Biol. 306 1115–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quiocho, F. A., Spurlino, J. & Rodseth, L. (1997) Structure (London) 5 997–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mueller, G. A., Choy, W. Y., Yang, D., Forman-Kay, J. D., Venters, R. A. & Kay, L. E. (2000) J. Mol. Biol. 300 197–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brunger, A. T., Adams, P. D., Clore, G. M., DeLano, W. L., Gros, P., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., Jiang, J. S., Kuszewski, J., Nilges, M., Pannu, N. S., et al. (1998) Acta Crystallogr. D 54 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maxwell, K. L. & Davidson, A. R. (1998) Biochemistry 37 16172–16182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goto, N. K., Skrynnikov, N. R., Dahlquist, F. W. & Kay, L. E. (2001) J. Mol. Biol. 308 745–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ganesh, C., Shah, A. N., Swaminahan, C. P., Surolia, A. & Varadarajan, R. (1997) Biochemistry 36 5020–5028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karplus, P. A. (1997) Protein Sci. 6 1302–1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fauchere, J. L. & Pliska, V. (1983) Eur. J. Med. Chem. 18 369–375. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quiocho, F. A. & Ledvina, P. S. (1996) Mol. Microbiol. 20 17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flocco, M. M. & Mowbray, S. L. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269 8931–8936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kellermayer, M. S. Z., Smith, S. B., Granzier, H. L. & Bustamante, C. (1997) Science 276 1112–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharff, A. J., Rodseth, L. E. & Quiocho, F. A. (1993) Biochemistry 32 10553–10559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee, B. & Richards, F. M. (1971) J. Mol. Biol. 55 379–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]