Abstract

We assessed the use of a joint activity schedule to increase peer engagement for preschoolers with autism. We taught 3 dyads of preschoolers with autism to follow joint activity schedules that cued both members of the pair to play a sequence of interactive games together. Results indicated that joint activity schedules increased peer engagement and the number of games completed for all dyads. Schedule following was maintained without additional prompting when activities were resequenced and when new games were introduced for 2 of the 3 dyads.

Keywords: activity schedules, autism, peer play, social interaction

Children with autism often play alone or become dependent on adult prompts to interact with peers (McClannahan & Krantz, 1999). Independent play skills of students with autism have been shown to improve with the use of photographic activity schedules, which are composed of a sequence of pictorial cues for children with disabilities to complete complex chains of behavior independently (McClannahan & Krantz). In the research that has examined the effects of activity schedules on social interactions (e.g., Krantz & McClannahan, 1993, 1998; Stevenson, Krantz, & McClannahan, 2000), interactions have involved 1 individual with autism following an activity schedule that prompts him or her to interact with a partner (adult or peer) who is not following an activity schedule and is simply available as a conversation partner. To date, no research studies have been published in which both members of a social pair follow the same activity schedule and complete a sequence of interactive games together. A joint activity schedule would potentially have the same benefits of an independent activity schedule, namely increasing independence and decreasing the need for adult prompts, plus the added features of promoting peer engagement in activities, turn taking, and cooperative play. A joint schedule may also prompt both students to move from one activity to another together, which could facilitate the following of classwide schedules used in typical educational environments. Thus, the purpose of the current study was to investigate whether inclusion of a joint activity schedule would result in higher levels of engagement for pairs of children with autism during interactive games.

Method

Participants and Setting

Three dyads of preschool-aged children participated. All were between the ages of 4 and 5 years, had diagnoses of autism, and were receiving intensive behavioral intervention in either university-based (Brady and David) or public-school-based (Ali and Dillon, Jackson and Nathan) preschools. With the exception of Ali, all participants were male. All children were identified as fluent followers of independent activity schedules, and each child could also select his or her own activities from a choice board (see McClannahan & Krantz, 1999, for specific fluency criteria). All research sessions were conducted in the play area of participants' classrooms, which contained a shelf with all the relevant games as well as the activity schedule (except in baseline and reversal probes), table, chairs, and a board that displayed the game choices for the choice pages. The board hung on a wall near the toy shelf and activity schedule.

Measurement

During all sessions, independent observers used a 20-s momentary time-sampling procedure to estimate the duration of peer engagement and to record prompts. Dyads were scored at each interval as being engaged, prompted, or unengaged. Dyads were scored as engaged if both participants were taking turns, using the game materials in the manner in which they were designed, cleaning up game materials, setting up game materials, obtaining or putting the game on the shelf, choosing a picture of the game from the choice board, initiating play (either independently or by following the appropriate script without additional prompting from an instructor), verbally interacting with a peer, turning the page of the activity schedule, attending to the picture depicted on the activity schedule, or walking between the schedule, game shelf, choice board, and table without prompting. An interval was scored as prompted when the instructor had his or her hands on one or both participants or when the instructor was shadowing one or both participants within a distance less than 1.5 m. Participants were scored as unengaged if they were engaged in behaviors other than those specified for engagement and were not being prompted by an instructor.

Interobserver agreement data were obtained in at least 30% of the sessions across all conditions. For an interval to count as an agreement, both observers had to agree on which game was being played; if the participants were engaged, prompted, or unengaged; and if they were engaged in the activity depicted on the schedule in each interval. Mean agreement was 91% (range, 84% to 100%) for Brady and David, 88% (range, 63% to 100%) for Ali and Dillon, and 92% (range, 71% to 100%) for Nathan and Jackson.

Procedure

Sessions lasted 20 min during baseline and reversal probe phases. In all other phases, sessions ended when all pages of the joint schedule were completed and varied in length, depending on how long it took to complete each game. Each session began with the children standing in front of the shelf containing the relevant games and when the data collector gave the instruction, “These are the games you can play with. Go play.” Six interactive games were concurrently available, which we chose due to availability, having a clear beginning and end, and allowing two people to play at the same time (e.g., Don't Break the Ice; Hungry, Hungry Hippos; Don't Spill the Beans; Crocodile Dentist). An adult instructor taught each child how to play appropriately with all of the games, and each participant demonstrated proficiency with all of the games prior to the beginning of the research. Children were considered proficient at the games when they could play and complete the game with no prompts to take turns, follow the rules of the game, and set up and clean up the game.

Baseline and Reversal Probe

The joint activity schedule was not present. Inappropriate behavior or attempts to interact with anyone other than the participating peer were ignored. Children were given the standard instruction to play, and no additional manual or verbal prompts were delivered. After the initial baseline, a baseline probe with the schedule present was conducted.

Teaching

A joint photographic activity schedule was displayed in a three-ring binder for each dyad. Each schedule book contained two prechosen activity pages followed by two choice pages (two games were designated for the prechosen activities and the remaining four games were used as choices). Each member of the dyads was responsible for one choice page and one prechosen activity page. The prechosen activity page included a picture of the responsible participant at the top and a picture of the game that was to be completed. The participant whose picture was depicted on a particular page was responsible for initiating play by reading the script “Let's play —.” Scripts were presented in full at the beginning of the teaching phase. The scripts were systematically faded from back to front by removing one word at a time until no words were on the page and the children continued to independently initiate play (scripts were eliminated for all children but Ali by the end of the evaluation). The choice pages also contained a picture of a participant at the top and a hook-and-loop dot where the picture of the chosen activity was to be placed.

In the beginning of the teaching condition, one of two instructors stood behind the participants. After the standard instruction was given, instructors used graduated guidance (MacDuff, Krantz, & McClannahan, 1993) to prompt the participants to engage in interactive play (e.g., taking turns during a board game or spinning a spinner) and following the schedule (e.g., pointing to the picture of the activity, obtaining the activity, turning the page). During this condition, the schedule pages remained in the same order with the same prechosen activities for each participant, and the same four games were available for the participants to choose for their choice pages.

Maintenance

During maintenance, the instructors were present but remained at least 1.5 m away from the participants. Prompts to engage were provided only if the participants did not initiate play within 5 s or emitted self-injury or aggression toward the peer.

Resequencing

To demonstrate that the specific sequence of the activities was not controlling student responding, the order in which the four pages were displayed was different each session (the prechosen activities remained the same for each participant, and the same four games were available for choice pages in this condition).

Generalization

Two of the original games were rotated in with four novel games in this condition. The two original games were available on the choice page, two of the novel games were selected for the prechosen pages, and the remaining two novel games were available as the other choices. This phase was implemented to test for generalization of engagement across novel games. Instructor prompts were reintroduced to increase peer engagement for Jackson during the generalization phase. Full manual prompts were used initially and were faded by introducing a brief delay and moving away from Jackson after the percentage of engagement was at or above 80% for two consecutive sessions.

A nonconcurrent multiple baseline design across dyads was used to assess the effects of a joint activity schedule on peer engagement.

Results and Discussion

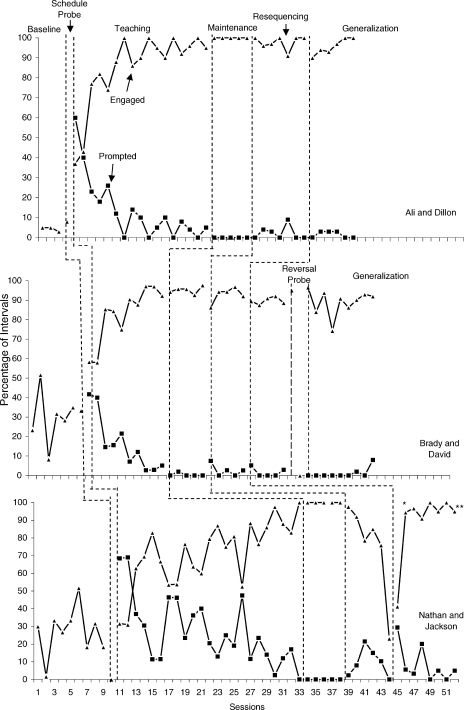

The percentage of intervals of engagement was low during baseline and the schedule probe for all dyads (Figure 1). Peer engagement rapidly increased during teaching and persisted above 80% during the maintenance phase with no prompting (Ali and Dillon and Nathan and Jackson) or a single prompt (Brady and David). Engagement persisted during resequencing and generalization phases for Ali and Dillon and for Brady and David. A brief reversal probe conducted with Brady and David, during which the joint activity schedule was removed, showed a decrease to 0% engagement by the second session; engagement increased immediately when the schedule was reintroduced. During resequencing with Nathan and Jackson, peer engagement became variable and began to decrease rapidly as the phase progressed. When the generalization phase began, engagement remained low. Graduated guidance with Jackson produced an immediate increase in responding that was maintained throughout the remainder of the phase.

Figure 1.

Results of the joint activity schedule intervention for Ali and Dillon (top), Brady and David (middle), and Nathan and Jackson (bottom). The asterisk represents the session in which manual prompts were reintroduced for Nathan and Jackson. The double asterisks represent the session in which those prompts were completely faded.

Our study extends the research on activity schedules by showing the efficacy of a joint activity schedule to increase peer engagement. All 3 pairs of children learned to follow the joint activity schedule and 2 of the 3 dyads maintained high levels of peer engagement when activities within the schedule were resequenced and new activities were introduced.

Although the activity schedule was effective in increasing peer engagement, the precise behavioral mechanisms responsible for its effectiveness are unclear. It is most plausible that the activity schedule functioned as a discriminative stimulus by signaling available activities for which engagement would be reinforced. Because programming reinforcement at the end of a schedule is generally recommended, it was interesting that the participants in this study completed the activity schedules without any programmed reinforcement mediated by an instructor. It is possible that the persistent engagement was governed by rules, but it seems more likely that playing games with the designated peers according to the schedule became a reinforcing event. Nonetheless, the behavioral mechanisms responsible for the effectiveness of activity schedules should be isolated in future research.

Although all 3 dyads were successfully taught to follow a joint activity schedule that promoted engagement, there were several limitations to this study. First, data on procedural fidelity were not taken on prompting and prompt-fading procedures. It is possible that variations in prompting occurred, which may account for some of the response patterns observed in the data. Second, levels of engagement deteriorated during the resequencing phase for Nathan and Jackson, necessitating the reintroduction of graduated guidance of engagement. Although engagement eventually increased and persisted after the prompts were faded, the reason for the decrease cannot be determined from the present data. Third, all the participants in this study were fluent followers of independent activity schedules, and most had an extensive verbal repertoire; these factors likely mediated the effects of our joint activity schedule. Fourth, our definition of peer engagement encompassed a variety of interactive and play behavior. Therefore, future researchers should examine if joint activity schedules are successful with students who do not have a history with independent activity schedules or who have less extensive verbal repertoires. Future researchers should also examine the extent to which specific social behaviors are affected by joint activity schedules.

Nevertheless, our preliminary data suggest that a joint activity schedule may be a promising tool to increase peer engagement and game play among children with autism. This strategy should eventually be compared to other effective means for increasing interactive play and engagement such as video modeling, discrete-trial training, and social stories.

Acknowledgments

We thank Henry Roane for his helpful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

References

- Krantz P.J, McClannahan L.E. Teaching children with autism to initiate to peers: Effects of a script-fading procedure. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1993;26:121–132. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1993.26-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krantz P.J, McClannahan L.E. Social interaction skills for children with autism: A script-fading procedure for beginning readers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1998;31:191–202. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1998.31-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDuff G.S, Krantz P.J, McClannahan L.E. Teaching children with autism to use photographic activity schedules: Maintenance and generalization of complex response chains. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1993;26:89–97. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1993.26-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClannahan L.E, Krantz P.J. Activity schedules for children with autism: Teaching independent behavior. Bethesda, MD: Woodbine House; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson C.L, Krantz P.J, McClannahan L.E. Social interaction skills for children with autism: A script-fading procedure for nonreaders. Behavioral Interventions. 2000;15:1–20. [Google Scholar]