Abstract

We used a brief training procedure that incorporated feedback and role-play practice to train staff members to conduct stimulus preference assessments, and we used group-comparison methods to evaluate the effects of training. Staff members were trained to implement the multiple-stimulus-without-replacement assessment in a single session and the paired-stimulus method in another single session. In all 16 cases (2 assessments for 8 trainees), correct responding increased to over 80% accuracy; in 14 of those 16 cases, it increased to over 90% accuracy. Thus, training produced mastery-level performance in a single training session in almost all cases.

Keywords: feedback, staff training, stimulus preference assessment

Stimulus preference assessments are often a necessary first step when developing behavioral programs for increasing appropriate behavior. Several studies have shown that items identified based on the results of preference assessments can serve as effective reinforcers for individuals with developmental disabilities (DeLeon & Iwata, 1996; Fisher et al., 1992; Pace, Ivancic, Edwards, Iwata, & Page, 1985). For this reason, the ability to conduct a preference assessment is an important skill for training staff who work with this population. However, only a few studies have evaluated training procedures for increasing skills involved in conducting preference assessments. Lavie and Sturmey (2002) successfully used instructions, modeling, and feedback to train staff members to conduct the paired-stimulus (PS) preference assessment (Fisher et al.) with children. A noteworthy feature of this study was that the training procedure took only 80 min to conduct.

Roscoe, Fisher, Glover, and Volkert (2006) later compared the relative effects of feedback and contingent money for training staff to implement the PS and multiple-stimulus-without-replacement (MSWO; DeLeon & Iwata, 1996) assessments. Across training conditions, sessions with simulated clients (adult playing the role of a client) were alternated with probe sessions with real clients (clients who had been referred to an outpatient clinic for the treatment of problem behavior). Results showed that feedback was necessary for facilitating skill acquisition, whereas contingent money had little effect. In addition, correct responding during probe sessions was similar to the simulated conditions, demonstrating that training using simulated clients readily transferred to situations involving real clients. Although the study by Roscoe et al. was informative in delineating the most useful training component, multiple opportunities to practice conducting preference assessments were provided prior to initiation of the feedback component, making it unclear whether rapid increases in performance would have been observed if trainees received only one or two training sessions prior to the feedback component. Therefore, the purpose of the current study was to extend this research by evaluating the most effective training component identified in Roscoe et al. after only one or two baseline sessions. Rapid acquisition after few practice opportunities would demonstrate that this training procedure could be implemented in an efficient manner in routine clinical settings with new staff members.

Method

Participants and Setting

Trainees

Eight recently hired behavioral technicians participated. Each held a bachelor's degree in psychology or a related discipline and had some experience working with individuals with disabilities. Conducting preference assessments was a regular component of their initial on-the-job training. None had received formal training on preference assessments. All had provided written informed consent to participate and were informed that their performance in this study would not be used as an evaluation of their job performance.

Simulated Clients, Setting, and Materials

Simulated clients were individuals who played the role of clients whose preferences were being assessed. All simulated clients had worked in an outpatient behavior program for at least 1 month. Sessions were conducted in a quiet room at a day-treatment program for individuals with developmental disabilities. Materials included a video camera and items necessary for conducting a preference assessment (i.e., table, chairs, leisure items, paper, pen, stopwatch, calculator).

Response Measurement and Interobserver Agreement

Staff members were trained to conduct both the PS and MSWO methods. For each trial in either the PS or MSWO assessments, there were two correct antecedent responses and one to three correct consequent responses, described below for each assessment method.

Response Definitions for PS Assessment

During each trial, the observer scored the first antecedent response as correct if the trainee placed two items spaced 30.5 cm apart in front of the client and instructed the client to “pick one.” The observer scored the consequence as correct if the client selected an item within 5 s, and the trainee removed the unselected item and provided access to the selected item for 5 s before initiating a new trial. If the client selected both items simultaneously or sequentially, the observer scored the consequence as correct if the trainee removed both items and reinitiated the same trial. If the client did not select an item within 5 s, the observer scored a correct consequence if the trainee removed both items, physically prompted the client to sample the items, and reinitiated the same trial. If the client did not select an item within 5 s or selected both items a second time, the observer scored a correct consequence if the trainee removed both items and initiated the next trial. If the client grabbed an item that was not presented, the observer scored a correct consequence if the trainee blocked access to or removed the item and continued with the current trial. Finally, at the end of the session, the trainee's data sheet was examined and one correct response was scored if the trainee recorded client selections on each trial, and a second correct response was scored if the trainee accurately summarized the client data, which consisted of obtaining a selection percentage and corresponding rank for each item.

Response Definitions for MSWO Assessment

Before the first trial, the observer scored a correct antecedent response if the trainee singly presented each item to the client for 30 s. Next, the observer scored a correct antecedent response if the trainee placed all items in a straight line or arc in front of the client and instructed the client to “pick one.” If the client selected an item within 30 s, the observer scored a correct consequence if the trainee provided access to that item for 30 s. After 30 s, the observer scored a correct consequence if the trainee removed the selected item, did not put the item back into the array, and rotated the remaining items. If the client selected two items sequentially, the observer scored a correct consequence if the trainee gave the client access to the item selected first for 30 s. If the client selected two items simultaneously, the observer scored a correct consequence if the trainee blocked access to both items and reinitiated the same trial. If the client again simultaneously selected two items, the observer scored a correct consequence if the trainee removed all items and initiated a new session. If the client did not select an item within 30 s, the observer scored a correct consequence if the trainee removed all items and initiated a new session. If the client grabbed another item while he or she had access to the one selected, the observer scored a correct consequence if the trainee blocked access to the item and continued with the current trial. Finally, at the end of the session, the trainee's data sheet was examined and one correct response was scored if the trainee recorded client selections on each trial, and a second correct response was scored if the trainee accurately summarized the client data, which consisted of obtaining a selection percentage and corresponding rank for each item.

Scripts Used During Simulated Assessments

The simulated clients followed one of three scripts when the trainees conducted the preference assessments. The three scripts for each type of preference assessment specified client responses for 16 preference assessment trials: five standard trials and 11 distracter trials. Standard trials were ones in which the simulated client selected one item within the first 5 s of the first or second presentation of the pair (PS assessment) or within 30 s of the presentation of the array of items (MSWO). During distracter trials, simulated client responses included (a) simultaneously selecting two stimuli (four trials), (b) selecting two stimuli sequentially in quick succession (one trial), (c) grabbing a stimulus that was not in the array (one trial), and (d) not selecting a stimulus within the appropriate time period (five trials). We exposed all trainees to all three scripts, which were ordered randomly across sessions.

Interobserver Agreement

Data were collected in vivo by trained observers who scored target responses with a paper and pencil; however, we videotaped all sessions to obtain interobserver agreement data. The dependent variable was the number of responses performed correctly (as defined above) divided by all possible responses for the first 16 trials, multiplied by 100%. A second observer independently collected data on 50% of the videotaped sessions. Observers' records were compared for each trial in which a response was recorded by one of the observers. An agreement was defined as both observers scoring the same response (either correct or incorrect). The number of agreements was divided by the number of agreements plus disagreements and multiplied by 100% to obtain a percentage agreement score. The mean agreement score for trainee behavior was 94% (range, 80% to 100%).

Experimental Design

We asked trainees to conduct a PS assessment in one condition and a MSWO assessment in the other condition across phases in accordance with a multielement design. During the baseline phase, the same procedure was conducted with all trainees. During the subsequent two phases, 4 trainees were assigned randomly to Group 1 and 4 were assigned randomly to Group 2. During the second phase, Group 1 received training for the MSWO assessment prior to the MSWO condition but were given no instructions or training for the PS assessment prior to the PS condition. Group 2 received training for the PS assessment prior to the PS condition but were given no instructions or training for the MSWO assessment prior to the MSWO condition. During the third phase, both groups received training for both assessments prior to both assessment conditions.

Training

Baseline (written Instruction)

During all conditions, we instructed trainees to formulate a list of the client's most to least preferred items. We gave trainees brief summaries of the PS and MSWO assessments from the method sections of Fisher et al. (1992) and DeLeon and Iwata (1996) for 30 min prior to sessions. Data sheets for each assessment also were provided.

Training (feedback and Role-Play Practice)

Immediately prior to each session, the experimenter reviewed the videotape and data sheet from the preceding session with the trainee (we used the baseline session for the first feedback session). The experimenter provided feedback by noting whether or not each target behavior depicted on the video and data sheet was performed correctly. Role playing was included to ensure multiple exposures to feedback within one training session. During role playing, the experimenter (playing the client) demonstrated each potential client response that may occur as indicated on the scripts. The trainee was instructed to respond (the correct consequent event was not specified). Immediately following trainee performances of each consequent event, the experimenter presented feedback in the manner described above. Training sessions were 15 to 20 min long.

Results and Discussion

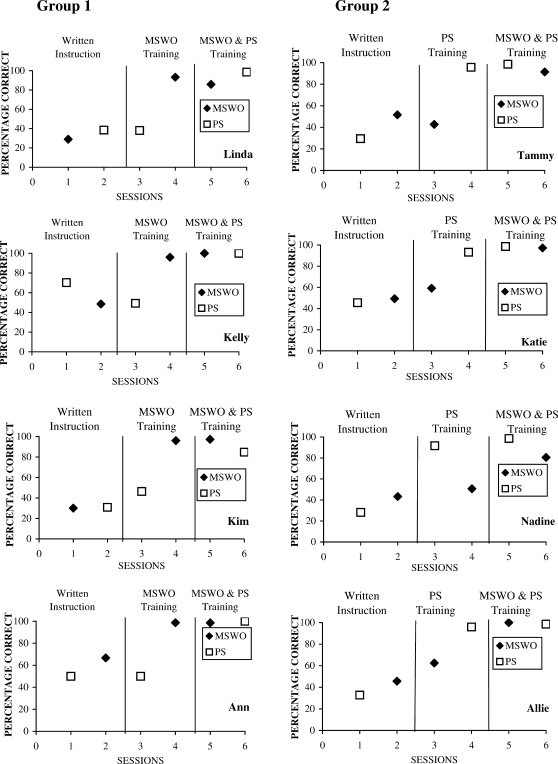

Figure 1 shows the results for Group 1 (who received the MSWO training first) and for Group 2 (who received the PS training first). During the written instruction phase, trainees showed moderate levels of correct performance when implementing the MSWO assessment in both Group 1 (M = 44%; range, 29% to 67%) and Group 2 (M = 47%; range, 43% to 52%). On the PS assessment, written instruction was associated with slightly better performance for Group 1 (M = 47%; range, 31% to 70%) than for Group 2 (M = 34%; range, 28% to 45%).

Figure 1.

The effects of feedback and role-play training during a single training session on the percentage of correct responses when implementing the PS and MSWO preference assessments. Group 1 (left) was trained on MSWO between the first and second phases and on PS between the second and third phases. Group 2 (right) was trained on PS between the first and second phases and on MSWO between the second and third phases.

Following training on the MSWO assessment, the mean performance of Group 1 increased to 96% (range, 93% to 99%), whereas without training, Group 2's performance increased to a mean of only 54% (range, 43% to 62%). The difference in performance between the trained (Group 1) and untrained (Group 2) trainees on the second administration of the MSWO assessment was statistically significant (F = 70.6; p < .001; df = 1, 5; with baseline scores as covariates). Following training on the PS assessment, the mean performance of Group 2 increased to 94% (range, 92% to 96%), whereas without training, Group 1 showed a slight decrease in performance to a mean of 46% (range, 38% to 50%). The difference in performance between the trained (Group 2) and untrained (Group 1) trainees on the second administration of the PS assessment was statistically significant (F = 226.7; p < .0001; df = 1, 5; with baseline scores as covariates). After all trainees received training on both assessments, the mean performance across all trainees was 95% (range, 81% to 100%) for the MSWO assessment and 96% (range, 85% to 100%) for the PS assessment. Inspection of individual data shows that each trainee showed small or no changes in their performances on the MSWO and PS assessments without training (mean change of 2 percentage points; range, −21 to 17 percentage points) and large improvements in their performances following training (mean change of 56 percentage points; range, 32 to 66 percentage points).

Overall, these findings indicated that an efficient and effective package could be developed to train new staff members in a single session to conduct the MSWO or PS assessments accurately. The current study replicates and extends the findings of Roscoe et al. (2006) by demonstrating that the most effective component identified (i.e., feedback) could be incorporated into an efficient training procedure that combined feedback and role-play practice for staff orientation and training programs in routine clinical settings. Correct responding increased to over 80% in all 16 cases (two assessments for 8 trainees) and over 90% in 14 cases. Thus, the training procedures produced mastery-level performance in a single session in almost all cases.

These outcomes could have been strengthened by demonstrating that training using simulated clients transferred to situations involving real clients. Although the probe data with real clients in Roscoe et al. (2006) demonstrated transfer of training, probes often followed multiple training sessions. Future research should examine the effects of the training procedure used in the present study with real clients after a single training session. Also, the training procedure might have been more efficient if it had been conducted in a group format. However, because it may not always be feasible to train several staff members concurrently (due to varying hire dates), it seemed to be more informative to evaluate the effects of within-participant training.

Acknowledgments

This investigation was supported in part by Grant 5 R01 MH69739-05 from the National Institute of Mental Health within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Eileen Roscoe is now at the New England Center for Children.

References

- DeLeon I.G, Iwata B.A. Evaluation of a multiple-stimulus presentation format for assessing reinforcer preferences. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1996;29:519–532. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W.W, Piazza C.C, Bowman L.G, Hagopian L.P, Owens J.C, Slevin I. A comparison of two approaches for identifying reinforcers for persons with severe and profound disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1992;25:491–498. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1992.25-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavie T, Sturmey P. Training staff to conduct a paired-stimulus preference assessment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2002;35:209–211. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2002.35-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace G.M, Ivancic M.T, Edwards G.L, Iwata B.A, Page T.J. Assessment of stimulus preference and reinforcer value with profoundly retarded individuals. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1985;18:249–255. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1985.18-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roscoe E.M, Fisher W.W, Glover A.C, Volkert V.M. Evaluating the relative effects of feedback and contingent money for staff training of stimulus preference assessments. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2006;39:63–77. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2006.7-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]