Abstract

Granulomatous experimental autoimmune thyroiditis (G-EAT) is induced by mouse thyroglobulin-sensitized splenocytes activated in vitro with mouse thyroglobulin and interleukin (IL)-12. Thyroid lesions reach maximal severity 20 days after cell transfer, and inflammation either resolves or progresses to fibrosis by day 60 depending on the extent of thyroid damage at day 20. Depletion of CD8+ T cells inhibits G-EAT resolution. Our previous studies indicated that IL-10 was generally higher in G-EAT thyroids that resolved. Using both wild-type and IL-10−/− CBA/J mice, this study was undertaken to determine whether G-EAT resolution would be inhibited in the absence of IL-10. The results showed that either depletion of CD8+ T cells or IL-10 deficiency increased fibrosis and inhibited resolution of inflammation. We also found a correlation between higher expression levels of proinflammatory cytokines and preferential expression levels of proapoptotic molecules, such as FasL and TRAIL, and antiapoptotic molecules, such as FLIP and Bcl-xL, in inflammatory cells from thyroids of both CD8-depleted and IL-10-deficient mice. Furthermore, many of the CD8+ T cells were also IL-10+. These results suggest that IL-10 plays an important role in G-EAT resolution and might promote resolution, at least in part, through its production in CD8+ T cells. Further understanding of the mechanisms that promote the resolution of inflammation will facilitate the development of novel strategies for treating autoimmune diseases.

Mouse thyroglobulin (MTg)-sensitized spleen cells activated in vitro with MTg and interleukin (IL)-12 induce a severe granulomatous form of experimental autoimmune thyroiditis (G-EAT) after transfer to syngeneic recipient mice.1,2,3 Thyroid lesions in G-EAT are characterized by infiltration of inflammatory cells and destruction of thyroid follicles.4,5,6,7,8 They reach maximal severity 20 days after cell transfer, and inflammation either resolves or progresses to fibrosis by day 60 depending on the extent of thyroid damage at day 20.4,5,6,7,8 CD4+ T cells are the primary effector cells for G-EAT4,5 and CD8+ T cells are required for G-EAT resolution.8 Although the mechanisms by which CD8+ T cells promote G-EAT resolution are not fully understood, cytokines produced by T cells are likely to play a pivotal role in both the development and outcome of G-EAT.

Interleukin-10 (IL-10), a cytokine produced by the Th2 subset of CD4+ T cells, and also by regulatory T cells (Treg), CD8+ T cells, B cells, and macrophages can both suppress and promote immune responses.9,10,11 IL-10 usually has protective rather than harmful effects in autoimmune diseases, including experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis,12,13 diabetes,14 collagen-induced arthritis,15,16,17 inflammatory bowel diseases,18,19 and autoimmune thyroid diseases.20,21,22,23,24,25 Although IL-10 has been shown to be inhibitory in autoimmune thyroid diseases, others have suggested IL-10 could be deleterious to the thyroid, by directing intrathyroidal B-cell stimulation.20 The function of IL-10 in autoimmune thyroid disease is still controversial and further studies are needed to clarify its function. Our previous studies showed that early resolution of G-EAT correlated with increased expression of IL-10 in thyroids, whereas chronic inflammation was associated with increased production of proinflammatory cytokines such as interferon (IFN)-γ and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α.26,27,28,29 In this study, IL-10−/− mice were used to test the hypothesis that G-EAT resolution would be delayed in the absence of IL-10, ie, IL-10 is one of the factors required for resolution of inflammation in G-EAT. The results indicate that G-EAT resolution was delayed in mice lacking IL-10. The effects of IL-10 deficiency were similar to those of CD8 depletion, which was shown in our previous studies to inhibit resolution of G-EAT.8,30 The results suggest that IL-10 promotes G-EAT resolution, and this may be attributable, at least in part, to its production by CD8+ T cells.

Materials and Methods

Mice

IL-10-deficient male NOD mice, provided by Dr. David Serreze (The Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were crossed with female NOD.H-2h4 mice that express the K haplotype on the NOD background. IL-10−/− NOD.H-2h4 mice were generated by selecting F2 mice that were homozygous for H-2Kk and the IL-10 neo insert. IL-10−/− CBA/J mice were generated by crossing IL-10−/− NOD.H-2h4 males with MHC-compatible H-2K CBA/J females. IL-10−/− F2 offspring with the CBA/J agouti coat color were selected and backcrossed to CBA/J for five generations. IL-10−/− mice, heterozygous littermates, and wild-type (WT) CBA/J mice were used for these experiments. WT, IL-10+/−, and IL-10−/− CBA/J mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions, and transferred to conventional housing for the experiments. IL-10−/− mice were given Baytril in their drinking water to inhibit development of inflammatory bowel disease.

Induction of G-EAT

IL-10+/−, IL-10−/−, and WT CBA/J mice generated in our breeding colony were injected intravenously twice at 10-day intervals with 150 μg of MTg prepared as previously described3 and 15 μg of lipopolysaccharide (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Seven days later, donor spleen cells were activated in vitro with 25 μg/ml of MTg and 5 ng/ml of IL-12 (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ) as previously described.5 Cells were harvested after 72 hours and 3 × 107 cells were transferred intravenously to 500 Rad-irradiated CBA/J, IL-10+/−, or IL-10−/− CBA/J mice. Recipient thyroids were evaluated 20 (peak of disease) or 60 days after cell transfer.5,30 In all experiments, IL-10−/− donor cells were transferred to IL-10−/− recipients and WT or IL-10+/− donor cells were transferred to WT or IL-10+/− recipients. Results using WT and IL-10+/− mice were indistinguishable, and both are referred to as WT CBA/J. Both male and female mice were used. Donor mice were generally 8 to 10 weeks old at the time of immunization, and recipients were 8 to 12 weeks old. All mice were bred and maintained in accordance with University of Missouri institutional guidelines for animal care. CD8+ T cells in WT recipient mice were depleted by administration of anti-CD8 mAb (ATCC HB129) 1 day after cell transfer and every 10 days thereafter as previously described.30 CD8+ T-cell depletion in recipients was determined to be nearly complete at day 20 and day 60 using flow cytometry, immunohistochemistry (IHC), and confocal microscopy.

Evaluation of G-EAT Histopathology and Fibrosis

Recipient thyroids were removed 20 or 60 days after cell transfer. One lobe of each thyroid was fixed in formalin, and paraffin-embedded tissues were sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Thyroids were scored for the extent of follicle destruction (G-EAT severity) using a scale of 0 to 5+ according to previously established criteria.4,5 1+ thyroiditis is defined as an infiltrate of at least 125 cells in one or several foci; 2+ is 10 to 20 foci of cellular infiltration involving up to 25% of the gland; 3+ indicates that 25 to 50% of the gland is infiltrated; 4+ indicates that >50% of the gland is destroyed; and 5+ indicates virtually complete destruction of the gland, with few or no remaining follicles. Thyroid lesions were also evaluated qualitatively. Granulomatous thyroid lesions had enlargement and proliferation of thyroid follicular cells, with numerous histiocytes, multinucleated giant cells, and increased numbers of neutrophils in addition to the mononuclear cell infiltration. The more severely inflamed granulomatous thyroids (4 to 5+ severity scores) also had microabscess formation, necrosis, and focal fibrosis, and inflammation extended beyond the thyroid to involve adjacent muscle and connective tissue. For evaluation of collagen deposition (fibrosis), some thyroid sections were stained using Masson’s trichrome.31

IHC

IHC staining for IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-17, IL-10, and IL-5 was described previously.26,27,32,33 After fixation and blocking, frozen thyroid sections were incubated with rat anti-IFN-γ (XMG1.2; American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD), rabbit anti-TNF-α (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), rabbit anti-IL17 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), goat anti-IL-10 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or rabbit anti-IL-5 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 60 minutes at room temperature. After incubation with the corresponding secondary biotinylated Ab (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA), immunoreactivity was demonstrated using the avidin-biotin complex immunoperoxidase system (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and developed using NovaRED (Vector Laboratories) or diaminobenzidine (Vector Laboratories) as the chromogen. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin. As a negative control, primary antibody (Ab) was replaced with an equal amount of normal rabbit, rat, or goat IgG; these controls were always negative.

Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and Reverse Transcriptase (RT)-PCR

Individual thyroid lobes were homogenized in TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and RNA was extracted as previously described in detail.34,35 IL-10 and IFN-γ mRNA was quantified by real-time PCR using the ABI 7000 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Amplification was performed for 40 cycles in a total volume of 30 μl and products were detected using SYBR Green (ABgene, Rockford, IL). The relative expression levels of triplicate samples were determined by normalizing expression of each target to HPRT. Expression level of each normalized sample is given as relative expression units. Real-time PCR primers for IL-10 are: sense: 5′-AGCAACCGTGGAGGACCA-3′, antisense: 5′-CCATCAGCAGGACCCTATAATCA-3′ and for IFN-γ are: sense: 5′-CAGCAACAACATAAGCGTCA-3′, antisense: 5′-CCTCAAACTTGGCAATACTCA-3′. RT-PCR was performed to determine the relative levels of CD4+ T cells and macrophages in thyroids of various groups as previously described in detail.34,35 RT-PCR primers for CD4 were described previously.27,28 Primers for F4/80 (a marker for macrophages) are sense: 5′-TTTCCTCGCCTGCTTCTTC-3′, antisense: 5′-CCCCGTCTCTGTATTCAACC-3′.

Western Blot

IL-10 and IFN-γ protein was quantified by Western blot with goat anti-IL-10 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and rat anti-IFN-γ (XMG1.2, American Type Culture Collection) by adding 30 μg of protein to a 15% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel as prescribed previously.27

Confocal Laser-Scanning Double-Immunofluorescence Microscopy

To detect differential expression of IL-10 by CD4+ or CD8+ T cells, B cells, or macrophages and expression of active caspase-3 by CD4+ or CD8+ T cells, dual-color immunofluorescence and confocal laser-scanning microscopy was performed as previously described27 using goat anti-IL-10 antibody or rabbit anti-active caspase-3 antibody (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) with rat anti-CD4 (GK1.5, American Type Culture Collection), anti-CD8 (53.6, American Type Culture Collection), anti-B220 (Caltag Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA) or anti-F4/80 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) Ab. Frozen sections of thyroids were used and IL-10 or active caspase-3 was visualized with Alexa 568 (red; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). CD4, CD8, B220, and F4/80 were visualized by Alexa 488 (green, Molecular Probes). Apoptosis was detected using an in situ cell death kit (Roche, Nutley, NJ) with formalin-fixed paraffin sections of thyroids as previously described.27,32 Slides were observed with a Radiance 2000 confocal system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) coupled to an IX70 inverted microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Culture of Primary CBA/J Mouse Thyroid Epithelial Cells (TECs)

Thyroid lobes from naïve CBA/J mice were aseptically dissected and disrupted mechanically to 12 to 14 fragments, then digested for 1 hour at 37°C in digestion medium consisting of 112 U/ml of type I collagenase and 1.2 U/ml of dispase II dissolved in Eagle’s minimal essential medium, shaking every 5 minutes. After centrifugation for 3 minutes at 1200 rpm, the pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of culture medium and seeded in 60-mm Petri plates (Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY) or in eight-well chamber slides (Nalge Nunc International, Rochester, NY), and cultured at 37°C.36 The culture medium was prepared as follows. Nu-Serum IV was diluted 2.5 times with F-12 medium, to give a concentration of 10% fetal bovine serum, 5 μg/ml of human transferrin, 10 μg/ml of bovine insulin, and 3.5 ng/ml of hydrocortisone. Medium was supplemented with 10 ng/ml of somatostatin and 2 ng/ml of glycyl-l-histidyl-l-lysine acetate. The purity of the thyroid cell population was verified by staining with cytokeratin and thyroglobulin. Cultured TECs used in this study are almost 100% pure TECs using these criteria.

Cytokine and Anti-Fas Treatment of Cultured TECs

Cultured TECs (70 to 80% confluent) were treated for 4 days with 100 IU/ml IFN-γ (eBioscience) and 50 IU/ml TNF-α (eBioscience) in the presence (5 to 20 ng/ml) or absence of recombinant mouse IL-10 (Peprotech). Cells were then treated overnight with 1 μg/ml of agonist anti-Fas (Jo-2, BD Pharmingen).36

Determination of Apoptosis of Cultured TECs

Apoptosis of cultured TECs was determined by terminal dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay using an Apoptag kit (Chemicon, Temecula, CA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. NovaRED (Vector Laboratories) was used for color development and slides were counterstained with hematoxylin. To quantify the number of apoptotic cells, all cells in five to six randomly selected high-power fields (magnification, ×400) were manually counted, and positive cells were expressed as a percentage of total cells.

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were repeated at least two or three times. Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test and/or the Mann-Whitney rank sum test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

G-EAT Resolution Is Inhibited and Fibrosis Is Promoted in CD8-Depleted WT and IL-10-Deficient Recipients

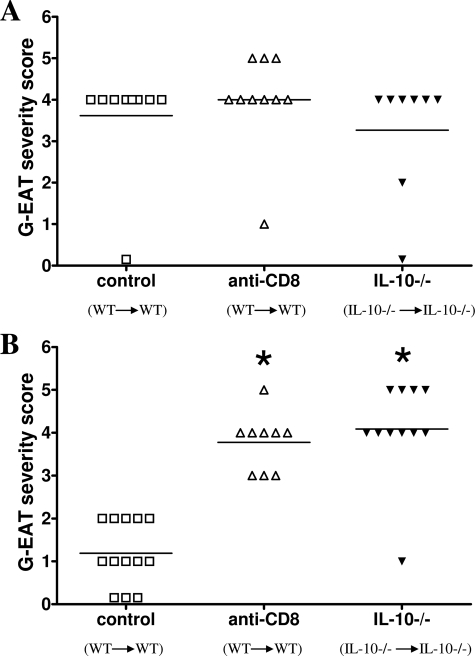

To test the hypothesis that G-EAT resolution would be inhibited in the absence of IL-10, splenocytes from MTg-sensitized CBA/J WT and IL-10−/− donors were activated in vitro with MTg and IL-12. WT donor cells were transferred to WT recipients and IL-10−/− cells were transferred to IL-10−/− recipients. G-EAT lesions in both groups reached maximal severity 20 days after cell transfer, and disease severity scores were similar (Figure 1A). At day 60, thyroid lesions in WT recipients of WT splenocytes had resolved or begun to resolve, whereas thyroid lesions in IL-10−/− recipients of IL-10−/− splenocytes had ongoing inflammation and fibrosis (Figure 1B). Similar results were observed when anti-IL-10 was given to WT recipients of splenocytes from WT donors (data not shown). The effects of IL-10 deficiency or IL-10 neutralization on G-EAT induction and resolution were similar to those seen after depletion of CD8+ T cells in WT recipients of WT donor cells (Figure 1, A and B). The difference in G-EAT severity between WT controls and the other two groups at day 60 was highly significant (P < 0.001), using both Student’s t-test and the Mann-Whitney rank sum test. In addition, there was extensive fibrosis in thyroids of both CD8-depleted WT recipients and IL-10−/− recipients at day 60, but fibrosis was minimal in thyroids of WT controls at day 60 (data not shown). These results indicate that depletion of CD8+ T cells in WT mice or IL-10 deficiency has little effect on induction of G-EAT, but G-EAT resolution is inhibited and fibrosis is promoted in CD8-depleted WT and IL-10−/− recipients.

Figure 1.

G-EAT resolution is inhibited in CD8-depleted WT and IL-10−/− recipients. G-EAT severity scores of individual mice 20 and 60 days after cell transfer are shown. Control: WT (donor) to WT (recipient); anti-CD8: WT (donor) to WT (recipient) given anti-CD8; IL-10−/−: IL-10−/− (donor) to IL-10−/− (recipient). A: Thyroid lesions in all groups reached maximal severity 20 days after cell transfer, and disease severity scores were similar with an average score of 3.3 to 4.0. B: By day 60, thyroid lesions in CD8-depleted WT and IL-10−/− recipients had ongoing inflammation (average severity score, 3.8 to 4.1), whereas thyroid lesions in WT controls had begun to resolve (average severity score, 1.2). Results are pooled from two separate experiments and are representative of five experiments. A significant difference between CD8-depleted WT and IL-10−/− recipients versus WT controls is indicated by the asterisk (P < 0.001).

Effect of CD8 Depletion and IL-10 Deficiency on Expression of Pro- and Anti-Inflammatory Cytokines

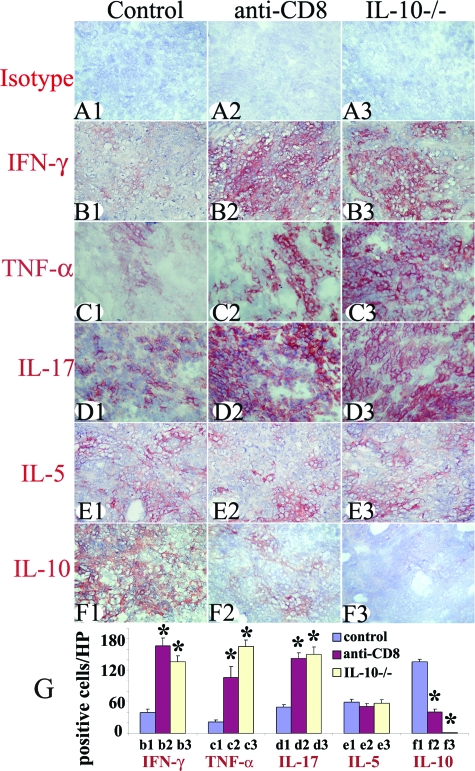

The balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines produced by thyroid-infiltrating inflammatory cells contributes to the outcome of G-EAT (resolution versus ongoing inflammation at day 60).21,26,27,28,37 At day 20, thyroids in all groups shown in Figure 1 expressed both proinflammatory (IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-17) and anti-inflammatory (IL-5 and IL-10) cytokines except no IL-10 was detected in thyroids of IL-10−/− recipients of IL-10−/− splenocytes (Figure 2). Staining intensity for proinflammatory cytokines was stronger in CD8-depleted WT and IL-10−/− recipients compared to WT controls. Conversely, staining intensity for the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 was stronger in thyroids of WT controls whose lesions would resolve at day 60 than in thyroids of CD8-depleted WT or IL-10−/− recipients in which there is ongoing inflammation at day 60 (Figure 2). The staining intensity for IL-5 was similar for all groups (Figure 2). Cytokine-positive cells (red) in five to six randomly selected high-power fields (magnification, ×400) were manually counted and the results are summarized in Figure 2G. These results suggest that the balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in thyroids might contribute to the duration or/and magnitude of thyroid inflammation that result in the distinct outcomes at day 60.

Figure 2.

Effect of CD8 depletion and IL-10 deficiency on protein expression of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines. Isotype control staining (A1–A3) was always negative. Representative thyroids in each group at day 20 expressed the proinflammatory cytokines IFN-γ (B1–B3), TNF-α (C1–C3), and IL-17 (D1–D3) and anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-5 (E1–E3) and IL-10 (F1–F3). The staining intensity for proinflammatory cytokines was stronger in thyroids of CD8-depleted WT and IL-10−/− recipients and staining intensity for IL-10 was weaker or undetectable compared to WT controls. The staining intensity for IL-5 was similar for all groups. Cytokine-positive cells (red) in five to six randomly selected high-power fields of three representative thyroids in each group were manually counted using an enlarged image. The results are summarized in G (bars b1–f3 correspond to B1–F3). A significant difference between CD8-depleted WT and IL-10−/− recipients versus WT controls is indicated by the asterisk (P < 0.05). Results are representative areas on slides from at least three individual mice examined per group with comparable G-EAT severity scores (4 to 5+). Original magnifications, ×400.

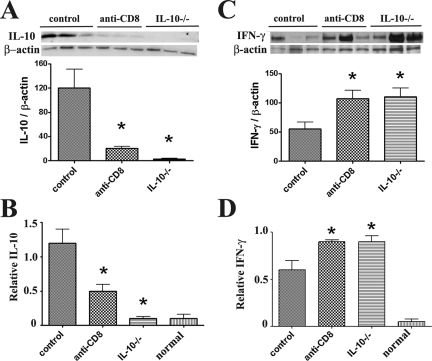

This was also supported by analysis of mRNA expression in thyroids. Consistent with the protein expression patterns in Figure 2, expression of proinflammatory cytokines IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-17 was higher, and IL-10 mRNA was lower in thyroids of CD8-depleted WT and IL-10−/− recipients compared to WT controls at day 20, even though G-EAT severity scores were similar (4 to 5+) for all groups. IL-5 mRNA was similar in all groups (data not shown), Consistent with the IL-10 expression pattern shown by IHC and RT-PCR, Western blot showed that IL-10 was undetectable in thyroids of IL-10−/− recipients of IL-10−/− splenocytes (Figure 3A) and IL-10 was lower in thyroids of CD8-depleted WT recipients compared to WT controls at day 20. Real-time quantitative PCR also indicated that IL-10 mRNA was undetectable in thyroids of IL-10−/− recipients of IL-10−/− splenocytes (Figure 3B) and IL-10 expression was lower in thyroids of CD8-depleted WT recipients compared to WT controls at day 20. Consistent with the expression pattern of IFN-γ by IHC and RT-PCR, both Western blot and real-time PCR showed that IFN-γ expression was higher in thyroids of CD8-depleted WT recipients and IL-10−/− recipients compared to WT controls (Figure 3, C and D).

Figure 3.

Quantitative determination of the effect of CD8 depletion and IL-10 deficiency on IL-10 and IFN-γ protein and mRNA expression At day 20, IL-10 protein was undetectable in thyroids of IL-10−/− recipients of IL-10−/− splenocytes (A) and IL-10 was lower in thyroids of CD8-depleted WT recipients compared to WT controls. Real-time quantitative PCR indicated that IL-10 mRNA was undetectable in thyroids of IL-10−/− recipients of IL-10−/− splenocytes (B) and IL-10 mRNA was lower in thyroids of CD8-depleted recipients compared to WT controls. IFN-γ protein (C) and mRNA (D) expression was higher in thyroids of CD8-depleted WT or IL-10−/− recipients compared to WT controls. For Western blot, 30 μg of protein from thyroids of each group (three individuals) was loaded in each lane and results are shown at the top in A and C. Results are expressed as the mean ratio of densitometric U/β-actin ± SEM (×100), and are representative of two independent experiments. For real-time PCR, bars are means of data for thyroids of four to five individual mice ± SEM. Results are expressed as the mean relative ratio to HPRT. A significant difference between CD8-depleted WT and IL-10−/− recipients versus WT controls is indicated by the asterisk (P < 0.05).

Cell Distribution of IL-10 Protein in Thyroids of CD8-Depleted WT Recipients and WT Controls

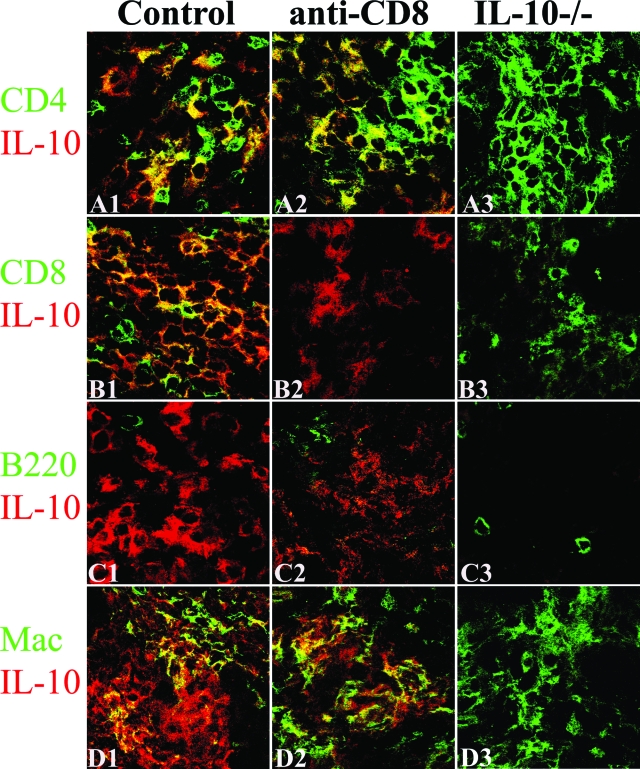

The finding that the effects of CD8 depletion and IL-10 deficiency on G-EAT resolution and cytokine expression in thyroids were similar (Figures 1 to 3) suggests that CD8+ T cells might be a major source of IL-10 in thyroids of WT mice with G-EAT. Dual-color immunofluorescence and confocal laser-scanning microscopy was used to determine what cells produce IL-10 in thyroids of CD8-depleted WT recipients and WT controls 20 days after cell transfer. As expected, IL-10 was undetectable in thyroids of IL-10−/− recipients of IL-10−/− splenocytes (Figure 4, A3–D3) and few CD8+ T cells were detected in thyroids of CD8-depleted WT recipients (Figure 4B2). IL-10 in thyroids of WT control mice was produced by CD4+ T cells (Figure 4A1; yellow, overlay), CD8+ T cells (Figure 4B1; yellow, overlay), and macrophages (Figure 4D1; yellow, overlay). Thyroids of recipients with G-EAT have very few B220+ cells,5,7 and no IL-10+ B220+ cells were detected (Figure 4, C1–C3). After depletion of CD8+ T cells, IL-10 was produced by CD4+ T cells (Figure 4A2; yellow, overlay) and macrophages (Figure 4D2; yellow, overlay).

Figure 4.

Cell distribution of IL-10 protein in thyroids of CD8-depleted recipients and WT controls. Dual-color immunofluorescence and confocal laser-scanning microscopy on thyroid frozen sections 20 days after cell transfer. CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, B cells, and macrophages were identified by cell surface expression of CD4, CD8, B220, or F4/80 (A1–D3, green), and IL-10-producing cells were identified by IL-10 staining (red). IL-10 was undetectable in thyroids of IL-10−/− recipients (A3–D3, red) and few CD8+ T cells were detected in CD8-depleted WT recipients (B2, green). IL-10 was produced by CD4+ T cells (A1, yellow, overlay), CD8+ T cells (B1, yellow, overlay), and macrophages (D1, yellow, overlay) in thyroids of WT controls. After depletion of CD8+ T cells, most IL-10 was produced by CD4+ T cells (A2, yellow, overlay) and macrophages (D2, yellow, overlay). No IL-10+ B cells were detected (C1–C3). CD8+ T cells (B1, yellow plus green) outnumbered CD4+ T cells (A1, yellow plus green) in WT controls, whereas CD4+ T cells outnumbered CD8+ T cells in CD8-depleted WT or IL-10−/− recipients (A1–A3 versus B1–B3). Shown are representative areas on slides of thyroids of at least three individual mice per group with comparable 4 to 5+ G-EAT severity scores. Original magnifications, ×800.

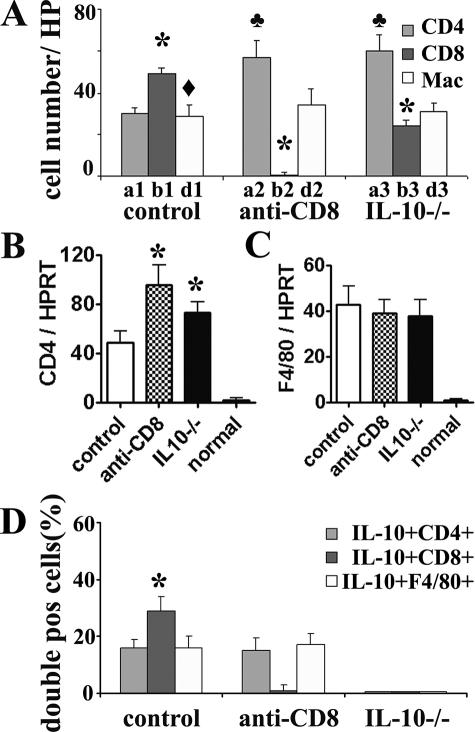

We previously showed26,27,28 that CD8+ T cells outnumbered CD4+ T cells at day 20 in thyroids that would resolve at day 60, whereas CD4+ T cells outnumbered CD8+ T cells at day 20 in thyroids that did not resolve and progressed to fibrosis at day 60. To determine whether this was also true for thyroids of IL-10−/− mice, numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in five to six randomly selected high-power fields (magnification, ×800) were manually counted (Figure 5A). These results indicate that thyroids of IL-10−/− mice have a CD4/CD8 ratio consistent with delayed resolution, because CD4+ T cells outnumber CD8+ T cells. Numbers of CD8+ T cells were higher than numbers of CD4+ T cells or macrophages in thyroids of WT controls. Thus, CD8+ T cells are predominant inflammatory cells in thyroids of WT controls at day 20.

Figure 5.

Effect of CD8 depletion on the percentages of IL-10-producing CD4+ T cells and macrophages. Numbers of CD4+, CD8+ T cells, and macrophages in five to six randomly selected high-power fields shown in Figure 4 (original magnifications, ×800) were manually counted and summarized in A (bars a1–d3 correspond to A1–D3 in Figure 4). A significant difference between CD8+ and CD4+ T cells in each group is indicated by the asterisk (P < 0.05). A significant difference between CD8+ T cells and macrophages in WT controls is indicated by the diamond (P < 0.05). A significant difference of CD4+ T cells in each group is indicated by the club (P < 0.05). mRNA was isolated from individual thyroid lobes 20 days after cell transfer and amplified as described in the Materials and Methods. B and C: Expression of CD4 and F4/80 mRNA is shown for each group including normal (naïve) mice. Results are expressed as the mean ratio of CD4 or F4/80 densitometric U/HPRT ± SEM (×100) of five to six mice per group, and are representative of two independent experiments. A significant difference between CD8-depleted WT or IL-10−/− recipients and WT controls is indicated by the asterisk (P < 0.05). D: IL-10+CD4+ cells (yellow, overlay in Figure 4, A1–A3), IL-10+CD8+ cells (yellow, overlay in Figure 4, B1–B3), and IL-10+F4/80+ cells (yellow, overlay in Figure 4, D1–D3) were manually counted in three to four randomly selected low-power fields (original magnifications, ×200) and expressed as the percentage of total CD4+ cells, CD8+ cells, or F4/80+ cells and summarized. The percentage of IL-10+CD8+ cells in thyroids of WT controls is significantly higher than that of IL-10+CD4+ or IL-10+F4/80+ cells in WT controls (P < 0.05).

Thyroids of CD8-depleted WT or IL-10−/− recipients had higher numbers of CD4+ T cells, but similar numbers of macrophages, compared to WT controls (Figure 5A). This is consistent with higher CD4 and similar F4/80 mRNA expression levels in thyroids of CD8-depleted WT or IL-10−/− recipients compared to WT controls (Figure 5, B and C). This suggests that CD8 depletion or IL-10 deficiency does not influence the numbers of thyroid infiltrating macrophages, but there are more infiltrating CD4+ T cells in these thyroids than in WT controls.

The increased numbers of CD8+ T cells in thyroids of WT controls could be cells that produce IL-10, or CD8+ T cells might produce another molecule that leads to increased production of IL-10 by CD4+ T cells or macrophages. To distinguish between these possibilities, IL-10+CD4+ cells, IL-10+CD8+ cells, and IL-10+F4/80+ cells were manually counted in three to four randomly selected low-power fields (magnification, ×200), and expressed as the percentage of total CD4+ cells, CD8+ cells, or F4/80+ cells. The results, summarized in Figure 5D, indicate that thyroids of CD8-depleted WT recipients and WT controls had similar percentages of IL-10-producing CD4+ T cells and macrophages, whereas there was a higher percentage of IL-10+CD8+ cells compared to IL-10+ CD4+ T cells or F4/80+ cells in WT controls. These results suggest that depletion of CD8+ T cells does not influence the percentages of IL-10-producing CD4+ T cells or macrophages, although there are relatively more CD4+ T cells in thyroids of CD8-depleted mice compared to controls. CD8+ T cells are a major source of IL-10 in thyroids of WT controls, suggesting that production of IL-10 by CD8+ T cells could contribute to the early resolution of G-EAT in these mice.

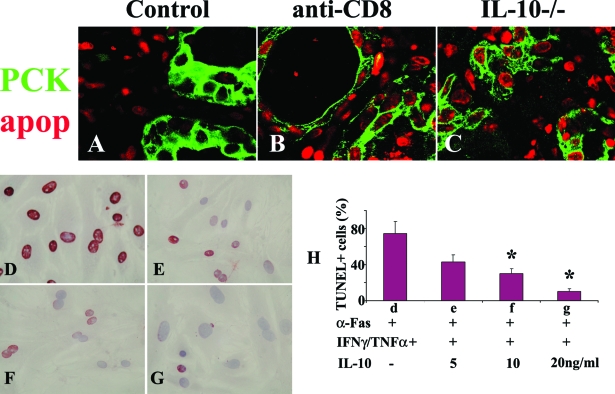

IL-10 Protects TECs from Fas-Mediated Apoptosis in Vivo and in Vitro

The results presented above indicate that resolution is inhibited in thyroids of IL-10−/− and CD8-depleted WT mice. A prolonged inflammatory response should be associated with decreased apoptosis of inflammatory cells and increased apoptosis of TECs. To determine whether this is true, a fluorescence apoptosis kit was used to determine the distribution of apoptotic cells in all groups (Figure 6, A–C). TECs were identified by pan-cytokeratin (PCK, green) and apoptosis was detected as red nuclear staining. In WT controls, most apoptotic cells (red) were inflammatory cells (Figure 6A), consistent with the early resolution of inflammation in this group. In contrast, there was less apoptosis of inflammatory cells and more apoptosis of TECs in thyroids of CD8-depleted WT (Figure 6B) and IL-10−/− recipients (Figure 6C) in which inflammation was prolonged. These results are consistent with the notion that IL-10 might protect TECs from apoptosis by promoting up-regulation of anti-apoptotic molecules such as FLIP and Bcl-xL.21,22,23,24 Expression of pro- and anti-apoptotic molecules on TECs versus infiltrating inflammatory cells in IL-10−/−, CD8-depleted, and control WT mice was examined and was found to correlate with the outcome of the inflammatory response. As shown previously, FasL (proapoptotic) and FLIP (antiapoptotic) were primarily expressed by TECs in thyroids of WT controls whose lesions would resolve, while these molecules were mainly expressed by inflammatory cells in thyroids of CD8-depleted WT and IL-10−/− recipients with chronic inflammation (data not shown). The proapoptotic molecule TRAIL and the anti-apoptotic molecule Bcl-xL were expressed primarily by TECs in thyroids of WT controls with early resolution and primarily on inflammatory cells in thyroids of CD8-depleted and IL-10−/− recipients with chronic inflammation (data not shown).

Figure 6.

IL-10 protects TECs from Fas-mediated apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. A–C: The distribution pattern of apoptotic cells in each group was determined by a fluorescence apoptosis kit. TECs were identified by pan-cytokeratin (PCK, green) and apoptosis was detected as red nuclear staining. Most apoptotic cells (red) were inflammatory cells in WT controls (A) and most were TECs in thyroids of CD8-depleted WT (B) and IL-10−/− recipients (C). Shown are representative areas on slides of thyroids of at least three individual mice per group with comparable G-EAT severity scores. Sixty to seventy percent confluent cultured TECs were pretreated with IFN-γ/TNF-α for 4 days in the presence (5 to 20 ng/ml) or absence of IL-10 and stimulated with anti-Fas for 20 hours. Apoptosis was detected by TUNEL staining. TUNEL+ cells (D–G, red) in five to six randomly selected high-power fields of three individual mice per group were manually counted and summarized in H (bars d–g correspond to D–G). In the absence of IL-10, TECs cultured with cytokines and anti-Fas underwent extensive Fas-mediated apoptosis (74 ± 13% TUNEL+ cells), whereas the percentage of TUNEL+ cells decreased in the presence of IL-10 in a dose-dependent manner. A significant difference in the percentage of TUNEL+ cells in the presence of different concentrations of IL-10 compared to no IL-10 is indicated by the asterisk (P < 0.05). Original magnifications: ×800 (A–C); ×400 (D–G).

TECs from normal mice can be sensitized in vitro by IFN-γ and TNF-α to undergo apoptosis induced by agonist anti-Fas (our unpublished data).36 To directly determine whether IL-10 can protect TECs from Fas-mediated apoptosis, 60 to 70% confluent cultured TECs were pretreated with IFN-γ and TNF-α for 4 days in the presence or absence of various concentrations of IL-10, and stimulated with agonist anti-Fas for 20 hours.36 Apoptosis was detected by TUNEL staining (Figure 6, D–G). TUNEL+ cells (red) in five to six randomly selected high-power fields of three individual mice per group (magnification, ×400) were manually counted and results are summarized in Figure 6H. In the absence of IL-10, TECs cultured in the presence of cytokines and anti-Fas underwent extensive Fas-mediated apoptosis (Figure 6D, 74 ± 13% TUNEL+ cells), whereas the percentage of TUNEL+ cells decreased in a dose-dependent manner in the presence of IL-10 (Figure 6, E–G). Minimal apoptosis was observed when TECs were cultured with anti-Fas in the absence of cytokines or with cytokines in the absence of anti-Fas (data not shown). Thus, these results show that IL-10 protects TECs from Fas-mediated apoptosis both in vivo and in vitro.

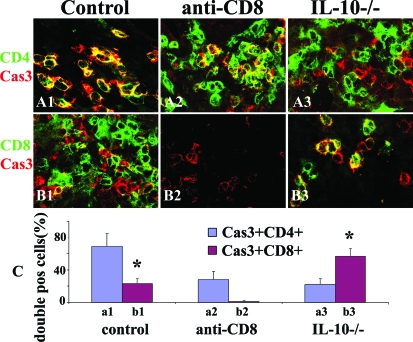

CD8+ T Cells in Thyroids of Mice with G-EAT Are Protected from Apoptosis by IL-10

Although most apoptotic cells in thyroids of WT controls are inflammatory cells and most apoptotic cells in thyroids of CD8-depleted WT and IL-10−/− recipients are TECs, there are apoptotic inflammatory cells in all groups at day 20 (Figure 6). Because CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are major inflammatory lymphocytes in G-EAT thyroids, it was important to determine whether the extent of apoptosis in CD4+ versus CD8+ T cells might differ in the different groups. Because the fluorescence apoptotic kit does not work well on frozen sections and CD4 and CD8 cannot be stained on paraffin sections,27 active caspase-3, a marker of apoptosis, was used to determine apoptosis of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Confocal staining of CD4 (Figure 7, A1–A3; green) or CD8 (Figure 7, B1–B3; green) on frozen sections with active caspase-3 (Figure 7, A1–B3; red) showed that although both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressed active caspase-3 (Figure 7; yellow, overlay) in all groups, most apoptotic inflammatory cells in WT controls are CD4+ T cells (Figure 7A1; yellow, overlay), whereas most in IL-10−/− thyroids are CD8+ T cells (Figure 7B3; yellow, overlay). Apoptotic CD4+ or CD8+ T cells were manually counted in five to six randomly selected high-power fields (magnification, ×800) and expressed as a percentage of total CD4+ or CD8+ T cells (summarized in Figure 7C). These results indicate that CD8+ T cells are mainly protected from apoptosis by IL-10, and an increased ratio of CD8+:CD4+ T cells is consistent with the earlier resolution of G-EAT in thyroids of mice that express IL-10.

Figure 7.

CD8+ T cells in thyroids of mice with G-EAT are protected from apoptosis by IL-10. Confocal staining of CD4 and CD8 on frozen sections with active caspase-3 at day 20. Active caspase-3 (red, A1–B3) is positive in both CD4+ (green, A1–A3) and CD8+ (green, B1–B3) T cells (yellow, overlay). Apoptotic (active caspase-3+) inflammatory cells in controls are mainly CD4+ T cells (A1, yellow, overlay), whereas most apoptotic cells in IL-10−/− recipients of IL-10−/− donor cells are CD8+ T cells (B3, yellow, overlay). Active caspase-3+CD4+ or active caspase-3+CD8+ cells were manually counted in five to six randomly selected high-power fields and expressed as the percentage of total CD4+ or CD8+ T cells and summarized in C. Shown are representative areas on slides of thyroids of at least three individual mice per group with comparable 4 to 5+ G-EAT severity scores. A significant difference between the percentage of active caspase-3+CD4+ and active caspase-3+CD8+ cells in WT controls or in IL-10−/− group is indicated by the asterisk (P < 0.05). Original magnifications, ×800.

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 plays an important role in G-EAT resolution, because resolution was inhibited in IL-10−/− recipients of IL-10−/− donor cells. Results obtained with IL-10−/− mice and WT recipients of WT donor cells in which IL-10 was neutralized were similar to those obtained when CD8+ T cells were depleted in WT recipients of WT donor cells, suggesting that one mechanism by which CD8+ T cells promote G-EAT resolution might be through production of IL-10. IL-10 both suppresses cell-mediated immunity and stimulates the humoral immune response.11 IL-10 inhibits production of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IFN-γ,9,11,38,39,40,41 and most studies show that IL-10 has protective or suppressive effects in experimental models of autoimmunity.12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,21,22,23,24,25 The results presented here are consistent with those findings, and extend earlier results by demonstrating that IL-10 might promote G-EAT resolution by promoting apoptosis of CD4+ T cells (Figure 7).

Several cell types, including CD8+ and CD4+ T cells and macrophages in thyroids of mice with G-EAT produce IL-10 (Figure 4). Depletion of CD8+ T cells and IL-10 deficiency correlated with increased expression of proinflammatory cytokines by inflammatory cells and with increased apoptosis of TECs and decreased apoptosis of CD4+ T cells in thyroids of IL-10−/− and CD8-depleted WT recipients. IL-10 deficiency and CD8 depletion both resulted in increased fibrosis, and G-EAT resolution was inhibited. CD8+ T cells can inhibit the effector phase of the immune response and promote resolution of inflammation through the Fas/FasL pathway30,42,43 or through the activity of CD122+CD8+ T cells.44 Therefore, IL-10 produced by CD8+ T cells could inhibit production of proinflammatory cytokines and up-regulate anti-apoptotic molecules on TECs, thus protecting TECs from apoptosis. After depletion of CD8+ T cells, G-EAT resolution was inhibited, and this could be attributable, at least in part, to decreased expression of IL-10 (Figures 2 and 3). Studies are in progress to further address this question.

IL-10 is produced by several subsets of regulatory T cells, some of which are CD4+ T cells. These include Th3 and Tr1 cells and CD4+CD25+ T cells that express Foxp3.45,46,47 In this study, Foxp3 mRNA and protein (data not shown) was similar, and TGF-β protein (data not shown) expression was higher in thyroids of CD8-depleted WT and IL-10-deficient mice compared to WT controls, suggesting that CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg and Th3 cells may not play a primary role in G-EAT resolution. TGF-β can be both anti-inflammatory and proinflammatory or profibrotic.48 In G-EAT, the profibrotic function of TGF-β is apparently dominant as shown in our earlier studies.31 CD4+ Tr1 cells produce both IL-10 and IFN-γ.47 Because IFN-γ is increased in thyroids of both IL-10−/− and CD8-depleted WT recipients, Tr1 cells are unlikely to be responsible for the results shown here. IL-10 is also produced by several subsets of CD8+ T cells that function as regulatory T cells.42,43,44,45,49,50,51 In this study, CD8+ T cells are a major source of IL-10 in thyroids of WT recipients of WT donor cells (Figures 2, 4, and 5), and depletion of CD8+ T cells had no effect on the percentages of thyroid-infiltrating IL-10-producing CD4+ T cells or macrophages. Because results in IL-10−/− and CD8-depleted WT recipients are basically identical (Figures 1 to 3 and 6), we hypothesize that IL-10 produced by CD8+ T cells might contribute, at least in part, to resolution of G-EAT in this model. Ongoing studies in which WT CD8+ T cells are transferred to IL-10−/− recipients of IL-10−/− effector cells are needed to prove this point.

Inflammation is attributable to an imbalance in production of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines. IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-17 are proinflammatory cytokines important for development and progression of most autoimmune diseases.37,52,53,54,55 Protein and mRNA expression levels of these cytokines (Figures 2 and 3, and data not shown) were increased in thyroids of CD8-depleted WT and IL-10−/− recipients with nonresolving inflammation and fibrosis, whereas IL-10 was lower or absent in these two groups. In contrast, thyroids of WT controls whose thyroid lesions resolved 60 days after cell transfer had lower expression of proinflammatory cytokines and increased IL-10 (Figures 2 and 3, and data not shown). The increased proinflammatory cytokines in thyroids of CD8-depleted and IL-10−/− recipients might contribute to the increased TEC apoptosis and follicle destruction. In this regard, we showed that neutralization of TNF-α or deficiency of IFN-γ promotes G-EAT resolution in this model.26,29 On the other hand, the increased IL-10 in thyroids of WT controls that will resolve, together with our previous studies showing increased IL-10 expression in thyroids of anti-TNF-α-treated WT recipients and in IFN-γ−/− and FLIP Tg+ recipients with G-EAT, all of which have early resolution of G-EAT,26,27,28,29 is consistent with the function of IL-10 as an anti-inflammatory molecule.21 Proinflammatory cytokines promote TEC apoptosis,21,27,28,36,55 and anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 can protect TECs from apoptosis as shown here (Figure 6) and by others.21 IL-10 protects cultured TECs from apoptosis by increasing FLIP and Bcl-xL and decreasing Fas on TECs (our unpublished data).21 IL-10 has been shown to protect other types of epithelial cells from Fas-mediated apoptosis,56 and to increase FasL expression on nonlymphoid cells, resulting in deletion of T cells and resolution of inflammation.50,57

The balance between pro- and anti-apoptotic molecules is important for resolution of inflammation,21,26,27,28,29,30,32 and our previous studies demonstrated a role for apoptosis through the Fas/FasL pathway in G-EAT resolution.27,28,30,33 As shown in our previous studies, the different outcomes of G-EAT correlate with distinct distribution patterns of pro- and anti-apoptotic molecules in thyroids that will resolve versus those in which resolution is inhibited, and results with IL-10−/− mice are consistent with those studies. Pro- and anti-apoptotic molecules were mainly expressed on TECs in thyroids of WT controls, and by infiltrating inflammatory cells in CD8-depleted WT and IL-10−/− recipients (data not shown). As indicated above, co-expression of pro- and anti-apoptotic molecules on TECs would protect TECs from apoptosis and apoptosis of inflammatory cells would be predominant, whereas co-expression of these molecules on inflammatory cells would protect inflammatory cells from apoptosis leading to chronic inflammation (Figure 6).

In conclusion, IL-10 and CD8+ T cells are both required for G-EAT resolution, and production of IL-10 by CD8+ T cells resulting in protection of TECs from apoptosis might be one of the mechanisms by which CD8+ T cells promote resolution of G-EAT. Further understanding of the mechanisms that promote resolution of inflammation will facilitate the development of novel strategies for treating autoimmune diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Daniel Schnurr and Alicia Duren for excellent technical assistance; and Drs. Vincent DeMarco, Shiguang Yu, and Prasanta Maiti for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Helen Braley-Mullen or Dr. Yujiang Fang, Division of Immunology and Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, University of Missouri, NE307, Medical Sciences, Columbia, MO 65212. E-mail: mullenh@health.missouri.edu or fangy@health.missouri.edu.

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant DK35527) and the Eastern Missouri Chapter of the Arthritis Foundation.

References

- Conaway DH, Giraldo AA, David CS, Kong YC. In situ analysis of T cell subset composition in experimental autoimmune thyroiditis after adoptive transfer of activated spleen cells. Cell Immunol. 1990;125:247–253. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(90)90078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lira SA, Martin AP, Marinkovic T, Furtado GC. Mechanisms regulating lymphocytic infiltration of the thyroid in murine models of thyroiditis. Crit Rev Immunol. 2005;25:251–262. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v25.i4.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braley-Mullen H, Johnson M, Sharp GC, Kyriakos M. Induction of experimental autoimmune thyroiditis in mice with in vitro activated splenic T cells. Cell Immunol. 1985;93:132–143. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(85)90394-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braley-Mullen H, Sharp GC, Bickel JT, Kyriakos M. Induction of severe granulomatous experimental autoimmune thyroiditis in mice by effector cells activated in the presence of anti-interleukin 2 receptor antibody. J Exp Med. 1991;173:899–912. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.4.899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braley-Mullen H, Sharp GC, Tang H, Chen K, Kyriakos M, Bickel JT. Interleukin-12 promotes activation of effector cells that induce a severe destructive granulomatous form of murine experimental autoimmune thyroiditis. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:1347–1358. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams WV, Kyriakos M, Sharp GC, Braley-Mullen H. The role of cellular proliferation in the induction of experimental autoimmune thyroiditis (EAT) in mice. Cell Immunol. 1986;103:96–104. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(86)90071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braley-Mullen H, Sharp GC. Adoptive transfer murine model of granulomatous experimental autoimmune thyroiditis. Int Rev Immunol. 2000;19:535–555. doi: 10.3109/08830180009088511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braley-Mullen H, McMurray RW, Sharp GC, Kyriakos M. Regulation of the induction and resolution of granulomatous experimental autoimmune thyroiditis in mice by CD8+ T cells. Cell Immunol. 1994;153:492–504. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1994.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Waal Malefyt R, Abrams J, Bennett B, Figdor CG, de Vries JE. Interleukin 10 (IL-10) inhibits cytokine synthesis by human monocytes: an autoregulatory role of IL-10 produced by monocytes. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1209–1220. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.5.1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pestka S, Krause CD, Sarkar D, Walter MR, Shi Y, Fisher PB. Interleukin-10 and related cytokines and receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:929–979. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann TR. Properties and functions of interleukin-10. Adv Immunol. 1994;56:1–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettelli E, Das MP, Howard ED, Weiner HL, Sobel RA, Kuchroo VK. IL-10 is critical in the regulation of autoimmune encephalomyelitis as demonstrated by studies of IL-10- and IL-4-deficient and transgenic mice. J Immunol. 1998;161:3299–3306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy MK, Torrance DS, Picha KS, Mohler KM. Analysis of cytokine mRNA expression in the central nervous system of mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis reveals that IL-10 mRNA expression correlates with recovery. J Immunol. 1992;149:2496–2505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennline KJ, Roque-Gaffney E, Monahan M. Recombinant human IL-10 prevents the onset of diabetes in the nonobese diabetic mouse. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1994;71:169–175. doi: 10.1006/clin.1994.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson AC, Hansson AS, Nandakumar KS, Backlund J, Holmdahl R. IL-10-deficient B10.Q mice develop more severe collagen-induced arthritis, but are protected from arthritis induced with anti-type II collagen antibodies. J Immunol. 2001;167:3505–3512. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.6.3505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnegan A, Kaplan CD, Cao Y, Eibel H, Glant TT, Zhang J. Collagen-induced arthritis is exacerbated in IL-10-deficient mice. Arthritis Res Ther. 2003;5:R18–R24. doi: 10.1186/ar601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasama T, Strieter RM, Lukacs NW, Lincoln PM, Burdick MD, Kunkel SL. Interleukin-10 expression and chemokine regulation during the evolution of murine type II collagen-induced arthritis. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:2868–2876. doi: 10.1172/JCI117993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powrie F, Coffman RL. Inhibition of cell-mediated immunity by IL4 and IL10. Res Immunol. 1993;144:639–643. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2494(05)80019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühn R, Lohler J, Rennick D, Rajewsky K, Muller W. Interleukin-10-deficient mice develop chronic enterocolitis. Cell. 1993;75:263–274. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80068-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Vega JR, Vilaplana JC, Biro A, Hammond L, Bottazzo GF, Mirakian R. IL-10 expression in thyroid glands: protective or harmful role against thyroid autoimmunity? Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;113:126–135. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00628.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stassi G, Di Liberto D, Todaro M, Zeuner A, Ricci-Vitiani L, Stoppacciaro A, Ruco L, Farina F, Zummo G, De Maria R. Control of target cell survival in thyroid autoimmunity by T helper cytokines via regulation of apoptotic proteins. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:483–488. doi: 10.1038/82725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourneur L, Damotte D, Marion S, Mistou S, Chiocchia G. IL-10 is necessary for FasL-induced protection from experimental autoimmune thyroiditis but not for FasL-induced immune deviation. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:1292–1299. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200205)32:5<1292::AID-IMMU1292>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batteux F, Trebeden H, Charreire J, Chiocchia G. Curative treatment of experimental autoimmune thyroiditis by in vivo administration of plasmid DNA coding for interleukin-10. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:958–963. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199903)29:03<958::AID-IMMU958>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mignon-Godefroy K, Rott O, Brazillet MP, Charreire J. Curative and protective effects of IL-10 in experimental autoimmune thyroiditis (EAT). Evidence for IL-10-enhanced cell death in EAT. J Immunol. 1995;154:6634–6643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangi E, Vasu C, Cheatem D, Prabhakar BS. IL-10-producing CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells play a critical role in granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-induced suppression of experimental autoimmune thyroiditis. J Immunol. 2005;174:7006–7013. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.7006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Wei Y, Sharp GC, Braley-Mullen H. Mechanisms of spontaneous resolution versus fibrosis in granulomatous experimental autoimmune thyroiditis. J Immunol. 2003;171:6236–6243. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.6236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y, Wei Y, DeMarco V, Chen K, Sharp GC, Braley-Mullen H. Murine FLIP transgene expressed on thyroid epithelial cells promotes resolution of granulomatous experimental autoimmune thyroiditis in DBA/1 mice. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:875–887. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y, DeMarco VG, Sharp GC, Braley-Mullen H. Expression of transgenic FLIP on thyroid epithelial cells inhibits induction and promotes resolution of granulomatous experimental autoimmune thyroiditis in CBA/J mice. Endocrinology. 2007;148:5734–5745. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Wei Y, Sharp GC, Braley-Mullen H. Decreasing TNFα results in less fibrosis and earlier resolution of granulomatous experimental autoimmune thyroiditis. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:306–314. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0606402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y, Chen K, Sharp GC, Yagita H, Braley-Mullen H. Expression and regulation of Fas and Fas ligand on thyrocytes and infiltrating cells during induction and resolution of granulomatous experimental autoimmune thyroiditis. J Immunol. 2001;167:6678–6686. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Wei Y, Sharp GC, Braley-Mullen H. Inhibition of TGFβ1 by anti-TGFβ1 antibody or lisinopril reduced thyroid fibrosis in granulomatous experimental autoimmune thyroiditis. J Immunol. 2002;169:6530–6538. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.11.6530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Wei Y, Sharp GC, Braley-Mullen H. Balance of proliferation and cell death between thyrocytes and myofibroblasts regulates thyroid fibrosis in granulomatous experimental autoimmune thyroiditis (G-EAT). J Leukoc Biol. 2005;77:166–172. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0904538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y, Chen K, Sharp GC, Braley-Mullen H. FLIP and FasL expression by inflammatory cells vs. thyrocytes can be predictive of chronic inflammation or resolution of autoimmune thyroiditis. Clin Immunol. 2003;108:221–233. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6616(03)00146-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H, Sharp GC, Chen K, Braley-Mullen H. The kinetics of cytokine gene expression in the thyroids of mice developing granulomatous experimental autoimmune thyroiditis. J Autoimmun. 1998;11:581–589. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1998.0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H, Sharp GC, Peterson K, Braley-Mullen H. IFN-γ-deficient mice develop severe granulomatous experimental autoimmune thyroiditis with eosinophil infiltration in thyroids. J Immunol. 1998;160:5105–5112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretz JD, Arscott PL, Myc A, Baker JR., Jr Inflammatory cytokine regulation of Fas-mediated apoptosis in thyroid follicular cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25433–25438. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y, Yu S, Braley-Mullen H. Contrasting roles of IFN-γ in murine models of autoimmune thyroid diseases. Thyroid. 2007;17:989–994. doi: 10.1089/thy.2007.0261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powrie F, Menon S, Coffman RL. Interleukin-4 and interleukin-10 synergize to inhibit cell-mediated immunity in vivo. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:3043–3049. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830231147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan FM, Feldmann M. Cytokines in autoimmunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 1996;8:872–877. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorentino DF, Zlotnik A, Mosmann TR, Howard M, O'Garra A. IL-10 inhibits cytokine production by activated macrophages. J Immunol. 1991;147:3815–3822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan C, Paik J, Vodovotz Y, Nathan C. Contrasting mechanisms for suppression of macrophage cytokine release by transforming growth factor-beta and interleukin-10. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:23301–23308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosiewicz MM, Alard P, Liang S, Clark SL. Mechanisms of tolerance induced by transforming growth factor-beta-treated antigen-presenting cells: CD8 regulatory T cells inhibit the effector phase of the immune response in primed mice through a mechanism involving Fas ligand. Int Immunol. 2004;16:697–706. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble A, Pestano GA, Cantor H. Suppression of immune responses by CD8 cells. I. Superantigen-activated CD8 cells induce unidirectional Fas-mediated apoptosis of antigen-activated CD4 cells. J Immunol. 1998;160:559–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YH, Ishida Y, Rifa'I M, Shi Z, Isobe K, Suzuki H. Essential role of CD8+CD122+ regulatory T cells in the recovery from experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2008;180:825–832. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.2.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevach EM. Regulatory T cells in autoimmunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:423–449. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annacker O, Pimenta-Araujo R, Burlen-Defranoux O, Barbosa TC, Cumano A, Bandeira A. CD25+CD4+ T cells regulate the expansion of peripheral CD4 T cells through the production of IL-10. J Immunol. 2001;166:3008–3018. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.5.3008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Garra A, Vieira PL, Vieira P, Goldfeld AE. IL-10-producing and naturally occurring CD4+ Tregs: limiting collateral damage. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1372–1378. doi: 10.1172/JCI23215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li MO, Wan YW, Sanjabi S, Robertson A, Flavell RA. Transforming growth factor-β regulation of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:99–147. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble A, Giorgini A, Leggat JA. Cytokine-induced IL-10-secreting CD8 T cells represent a phenotypically distinct suppressor T-cell lineage. Blood. 2006;107:4475–4483. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-3994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreiro R, Lucker G, Herndon J, Ferguson TA. Termination of antigen-specific immunity by CD95 ligand (Fas ligand) and IL-10. J Immunol. 2004;173:1519–1525. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson TA, Griffith TS. A vision of cell death: Fas ligand and immune privilege 10 years later. Immunol Rev. 2006;213:228–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington L, Hatton RD, Mangan PR, Turner H, Murphy TL, Murphy KM, Weaver CT. Interleukin 17-producing CD4+ effector T cells develop via a lineage distinct from the T helper type 1 and 2 lineages. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1123–1132. doi: 10.1038/ni1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong C. Diversification of T-helper-cell lineages: finding the family root of IL-17-producing cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:329–333. doi: 10.1038/nri1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seder RA, Paul WE. Acquisition of lymphokine-producing phenotype by CD4+ T cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:635–673. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.003223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SH, Bretz JD, Phelps E, Mezosi E, Arscott PL, Utsugi S, Baker JR., Jr A unique combination of inflammatory cytokines enhances apoptosis of thyroid follicular cells and transforms nondestructive to destructive thyroiditis in experimental autoimmune thyroiditis. J Immunol. 2002;168:2470–2474. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.5.2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharhani MS, Borojevic R, Basak S, Ho E, Zhou P, Croitoru K. IL-10 protects mouse intestinal epithelial cells from Fas-induced apoptosis via modulating Fas expression and altering caspase-8 and FLIP expression. Am J Physiol. 2006;291:G820–G829. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00438.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfoco E, Stuart PM, Brunner T, Lin T, Griffith TS, Gao Y, Nakajima H, Henkart PA, Ferguson TA, Green DR. Inducible nonlymphoid expression of Fas ligand is responsible for superantigen-induced peripheral deletion of T cells. Immunity. 1998;9:711–720. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80668-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]