Abstract

Cardiomyopathy is a serious disorder of the heart muscle and, although rare, it is potentially devastating in children. Funded by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute since 1994, the Pediatric Cardiomyopathy Registry (PCMR) was designed to describe the epidemiology and clinical course of selected CMs in patients 18 years old or younger and to promote the development of etiology-specific prevention and treatment strategies. Currently, data from more than 3,000 children with cardiomyopathy have been entered in the PCMR database with annual follow-up continuing until death, heart transplant, or loss-to-follow up. Using PCMR data, the incidence of cardiomyopathy in two large regions of the United States is estimated to be 1.13 cases per 100,000 children. Only 1/3 of children had a known etiology at the time of cardiomyopathy diagnosis. Diagnosis was associated with certain patient characteristics, family history, echocardiographic findings, laboratory testing, and biopsy. Greater incidence was found in boys and infants (<1 yr) for both dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (DCM, HCM) and black race for only DCM. In DCM, prognosis is worse in older children (>1yr), heart failure (HF) at diagnosis or idiopathic etiology. For HCM, worse prognosis is associated with inborn errors of metabolism or combination of HCM and another cardiomyopathy functional type. The best outcomes were observed in children presenting at age >1 yr with idiopathic HCM. PCMR data have enabled analysis of patients with cardiomyopathy and muscular dystrophy, as well as Noonan Syndrome. Currently, collaborations with the Pediatric Heart Transplant Study group and a newly established Pediatric Cardiomyopathy Biologic Specimen Repository at Texas Children’s Hospital will continue to yield important results. The PCMR is the largest and most complete multi-center prospective data resource regarding the etiology, clinical course and outcomes for children with cardiomyopathy.

Introduction

In 1994, the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) provided funding for the establishment of the Pediatric Cardiomyopathy Registry (PCMR), a large, multicenter observational study of primary and idiopathic cardiomyopathies in children. The PCMR was designed to describe the epidemiology and clinical course of selected cardiomyopathies in patients 18 years old and younger, and to promote the development of etiology-specific prevention and treatment strategies. Currently, data from more than 3,000 children with cardiomyopathy have been entered in the PCMR database with annual follow-up continuing until death, heart transplant, or loss-to-follow up. The aims of the PCMR have evolved over the 14 years of continuous NHLBI funding. The original aims were primarily epidemiological with the establishment of retrospective and prospective cohorts to estimate the incidence and outcome in children with cardiomyopathies overall, as well as within subgroups defined by gender, age, race, and geographic residence. In the second grant cycle, parent-reported functional status data were prospectively collected to better characterize the impact of cardiomyopathy on the daily lives of affected children and their families. In addition, clinical data collection continued to refine estimates of incidence, outcome and outcome predictors for each functional type of cardiomyopathy (i.e., dilated, hypertrophic, restrictive, and mixed type). In the current funding cycle, study aims were expanded through collaboration with the Pediatric Heart Transplant Study Group to examine the effect of cardiac transplantation on the clinical course of cardiomyopathy, as well as to establish the longitudinal course of functional status and its relationship to clinical events and outcomes, including heart transplantation. Finally, for the first time since the establishment of the Registry biological specimens (blood and cardiac tissue) are being collected to begin to investigate the relationship of genetic and viral markers with clinical and functional outcomes.

Analyses of the PCMR database have resulted in important findings regarding the incidence of cardiomyopathy in children, determination of the etiology of these cardiomyopathies, precise estimates of mortality and cardiac transplantation outcomes, determinants of outcomes for children with dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, the clinical course of children with cardiomyopathies and dystrophinopathies, and historical patterns of therapy. This paper reviews prominent PCMR findings and describes the current ongoing research studies associated with the PCMR.

Methods

The PCMR design and implementation are presented in detail elsewhere.1 In brief, patients aged 18 years or less diagnosed with cardiomyopathy at participating centers are eligible for inclusion in the PCMR. Patients with specific secondary causes of myocardial abnormalities were excluded, including but not limited to potential causes of myocardial hypertrophy such as congenital heart disease and exposure to drugs known to cause cardiac hypertrophy (Table 1). Each case is classified according to morphology as dilated, hypertrophic, restrictive, mixed, or other type of cardiomyopathy. Cases are enrolled in the Registry if they met certain quantitative echocardiographic criteria, if the pattern of cardiomyopathy conforms to a defined semiquantitative pattern, or if the diagnosis is confirmed by tissue analysis (Table 2).

Table 1.

Exclusionary Criteria for the Pediatric Cardiomyopathy Registry

| • | Endocrine disease known to cause heart muscle disease (including infants of diabetic mothers). |

| • | History of rheumatic fever. |

| • | Toxic exposures known to cause heart muscle disease (e.g., anthracyclines, mediastinal radiation, iron overload, or heavy metal exposure). |

| • | HIV infection or born to an HIV positive mother. |

| • | Kawasaki disease. |

| • | Congenital heart defects unassociated with malformation syndromes (e.g., valvar heart disease or congenital coronary artery malformations). |

| • | Immunologic disease. |

| • | Invasive cardiothoracic procedures or major surgery during the preceding month except those specifically related to cardiomyopathy including LVAD, ECMO and AICD placement. |

| • | Uremia, active or chronic. |

| • | Abnormal ventricular size or function that can be attributed to intense physical training or chronic anemia. |

| • | Chronic arrhythmia unless there are studies documenting inclusion criteria prior to the onset of arrhythmia (except a patient with chronic arrhythmia, subsequently ablated, whose cardiomyopathy persists after two months is not to be excluded). |

| • | Malignancy. |

| • | Pulmonary parenchymal or vascular disease (e.g., cystic fibrosis, cor pulmonale, or pulmonary hypertension). |

| • | Ischemic coronary vascular disease. |

| • | Age >18 years. |

| • | Association with drugs known to cause hypertrophy (e.g., growth hormone, corticosteroids or cocaine) |

LVAD, left ventricular assist device; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; AICD, automatic implantable cardioverter defibrillator

Table 2.

Inclusionary Echocardiographic Criteria for the Pediatric Cardiomyopathy Registry

| Measurements | |

| • | Left ventricular fractional shortening or ejection fraction >2 s.d. below the normal mean for age. Fractional shortening is acceptable in patients with normal ventricular configuration and no regional wall motion abnormalities. Abnormal ejection fraction by echocardiography, radionuclide or contrast angiography, or MRI are acceptable alternatives but age-appropriate norms for the individual laboratory must be employed. |

| • | Left ventricular posterior wall thickness at end-diastole >2 s.d. above the normal mean for body-surface area. |

| • | Left ventricular posterior wall thickness at end-diastole >2 s.d. below the normal mean for body-surface area. |

| • | Left ventricular end-diastolic dimension or volume >2 s.d. above the normal mean for body-surface area. Dimension data are acceptable under the conditions outlined for fractional shortening above, and volume data may be derived from the imaging methods as above. |

| Patterns | |

| • | Localized ventricular hypertrophy: such as, septal thickness > 1.5 × left ventricular posterior wall thickness with at least normal left ventricular posterior wall thickness, with or without dynamic outflow obstruction. |

| • | Restrictive cardiomyopathy: one or both atria enlarged relative to ventricles of normal or small size with evidence of impaired diastolic filling and in the absence of significant valvar heart disease. |

| • | Contracted form of endocardial fibroelastosis: similar to restrictive cardiomyopathy plus echo-dense endocardium. |

| • | Ventricular dysplasia/Uhl's anomaly: very thin right ventricle with dilated right atrium (usually better assessed by MRI than by echo). |

| • | Concentric hypertrophy in the absence of hemodynamic cause: a single measurement criterion of LV posterior wall thickness at end-diastole > 2 s.d. would suffice. |

| • | Left ventricular myocardial noncompaction: very trabeculated spongiform left ventricle myocardium with multiple interstices. |

Data collection relies on two mechanisms. Voluntary submission of data has accrued from nearly 100 private and institutional participating centers in the United States and Canada. In addition, from 1994 to 2004, two geographic regions were targeted for comprehensive patient recruitment, comprised of a Central Southwest region (Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Texas) and the New England region (Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island), in order to estimate accurately the incidence of cardiomyopathy in children. Standardized data collection in these regions was performed by an outreach team that travels to the participating centers to enroll new cases and abstract relevant data from medical records at regular intervals.

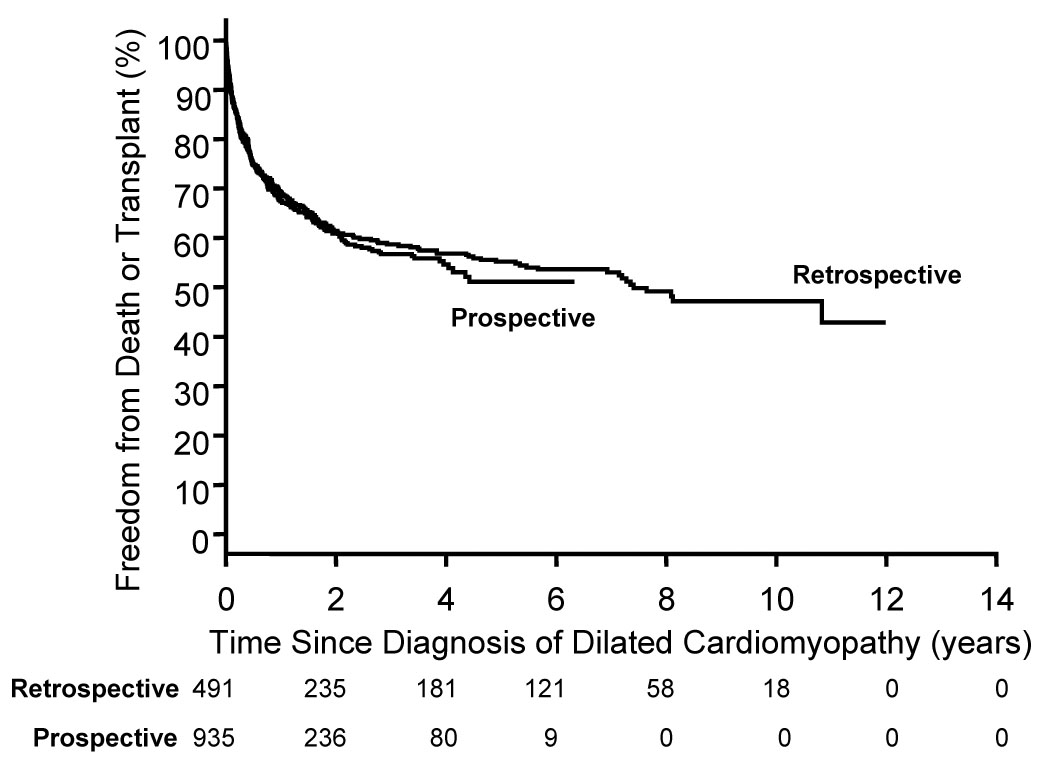

Registry patients are classified into two cohorts: a prospective cohort comprised of all patients diagnosed with cardiomyopathy after January 1, 1996; and a retrospectively obtained cohort comprised of patients diagnosed with cardiomyopathy between 1990 and 1995. The prospective cohort is largely enrolled from the two geographic regions described above to address PCMR incidence epidemiologic aims. Data collection includes demographic descriptors, quantitative echocardiographic measurements, brief family history, vital and transplant status, and clinical findings. The retrospective cohort database was created using a more detailed data collection protocol in order to address clinical aims. Additional data collection included detailed family history, qualititative echocardiographic assessment (e.g., mitral regurgitation), rhythm data, therapy, and hospitalizations. Clinical characteristics and echocardiographic findings are similar between the retrospective and prospective cohorts2, and there was no significant difference in clinical outcomes between the two cohorts (Figure 1) Therefore, for most registry analyses, with the exception of incidence rate estimation, the two cohorts are combined.

Figure 1.

Estimated freedom from death or transplant for patients with pure dilated cardiomyopathy (P=0.710) by cohort (retrospective: diagnosed 1990 to 1995, 491 patients; prospective: diagnosed 1996 to 2002, 935 patients).

Epidemiology of Pediatric Cardiomyopathy

From 1996 to 1999, 467 patients with a new diagnosis of cardiomyopathy meeting PCMR criteria were identified in the two geographic regions described above. There were 18 pediatric cardiology centers in the New England region and 20 in the Central Southwest. Completeness of case capture was assessed in multiple ways and it is estimated that fewer than 5 cases per year were missed.3 The estimated annual incidence of pediatric cardiomyopathy in the United States based on these two regions is 1.13 cases per 100,000 for persons 18 years of age or younger.3 This estimate is comparable to incidence reports from Finland4 and Australia.5 Incidence was significantly higher in infants less than one year of age (8.34 cases per 100,000 children per year, 95% confidence interval 7.21–9.61). Incidence was higher in boys than girls (1.32 vs. 0.92 per 100,000/year, P<0.001), blacks as compared with whites (1.47 vs. 1.06 per 100,000/year, P=0.02), and in the New England region compared to the Central Southwest (1.44 cases vs. 0.98 per 100,000/year; P<0.001). The annual incidence of dilated cardiomyopathy was 0.57 cases per 100,000; the incidence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy was 0.47 per 100,000/year.2,6 The incidence of cardiomyopathy may potentially be underestimated because children with sudden death as their presenting symptom may not have been identified as pathologists and medical examiners were not contacted in the original protocol. Children with asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction would also not be identified until they seek medical evaluation; however, the PCMR definition of cardiomyopathy is based on clinically present disease.

Establishing a Causal Diagnosis for Children with Cardiomyopathy

Only about one third of children have a known etiology at the time of cardiomyopathy diagnosis. Data from the 916 patients from the PCMR retrospective cohort diagnosed between January 1, 1990 and December 31, 1995, were analyzed to determine what demographic, family history, echocardiographic findings, the use of laboratory testing and biopsy were associated with establishing a causal diagnosis in children with primary or idiopathic cardiomyopathy.7 For children with dilated cardiomyopathy (54%), establishing a causal diagnosis was associated univariately with older age at diagnosis, smaller left ventricular dimensions and a higher shortening fraction. Children with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (32%) were more likely to have a causal diagnosis if they were female, had decreased height and weight for age, and higher shortening fraction. Family history of cardiomyopathy, genetic syndromes, or sudden death was also associated with establishing a causal diagnosis in hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy patients. Multivariate models adjusting for age at diagnosis, congestive heart failure, and geographic region, after exclusion of cases with neuromuscular disease, familial isolated cardiomyopathy, and malformation syndromes, demonstrated that, children with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy who had metabolic blood and urine testing were 6.4 times as likely to have a causal diagnosis established than patients without such testing. In dilated cardiomyopathy patients, multivariate analysis identified viral serology or culture and endomyocardial biopsy as significant independent predictors of a causal diagnosis (odds ratios, 1.81 and 4.84, respectively).

Outcomes for Children with Cardiomyopathy

Analyses of the PCMR database have resulted in recent reports identifying cause-specific outcomes for children with dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathies. Clinical outcomes were death or the composite of the earliest occurring of death or heart transplantation.

Towbin et al.2 reported on 1426 “pure” cases of dilated cardiomyopathy in the PCMR database. Causal subgroups for dilated cardiomyopathy were idiopathic (66%), myocarditis (16%), neuromuscular disorders (9%), familial dilated cardiomyopathy (5%), inborn metabolic errors (4%), or malformation syndromes (1%). Five-year freedom from death and transplant was lowest for patients from the idiopathic subgroup (Figure 2). Children aged 6 years or older were more likely to die or receive heart transplant compared with younger children (p< 0.001). Using multivariate Cox regression modeling, after exclusion of patients with neuromuscular disease and inborn metabolic errors, dilated cardiomyopathy patients with an idiopathic diagnosis (compared to known diagnosis) the presence of congestive heart failure at diagnosis, and decreased left ventricular shortening fraction z-score were significant predictors of the composite endpoint of death or receive heart transplantation. In conclusion, outcomes for children with dilated cardiomyopathy depend on cause, age at diagnosis, and heart failure at presentation. Most children do not have a cause for dilated cardiomyopathy, which limits the application of disease-specific therapy.

Figure 2.

Freedom from death or transplantation for patients with pure dilated cardiomyopathy.

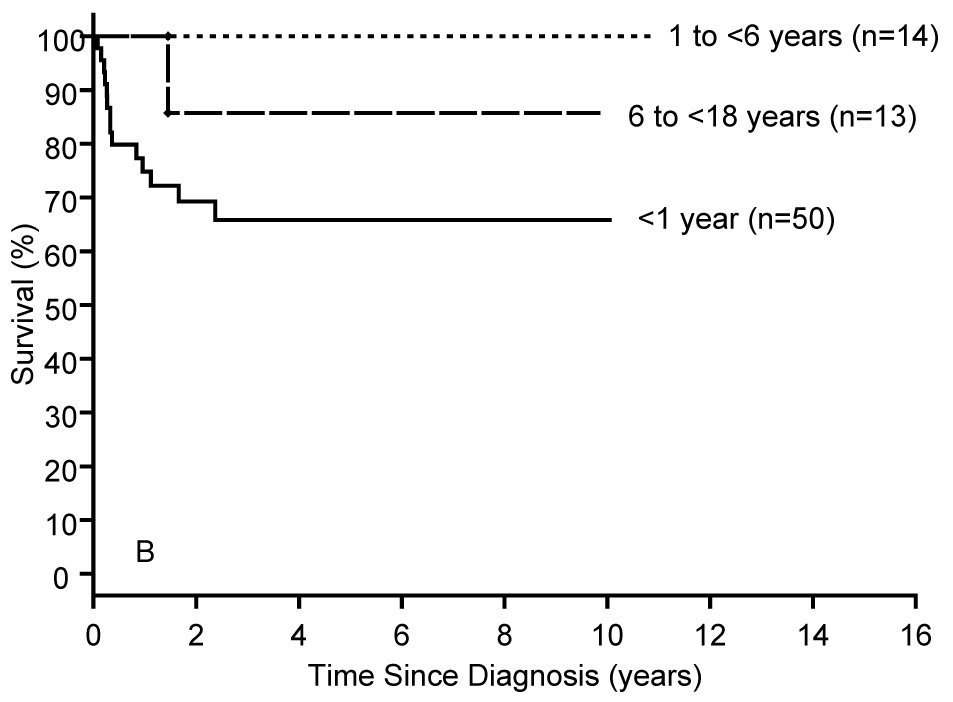

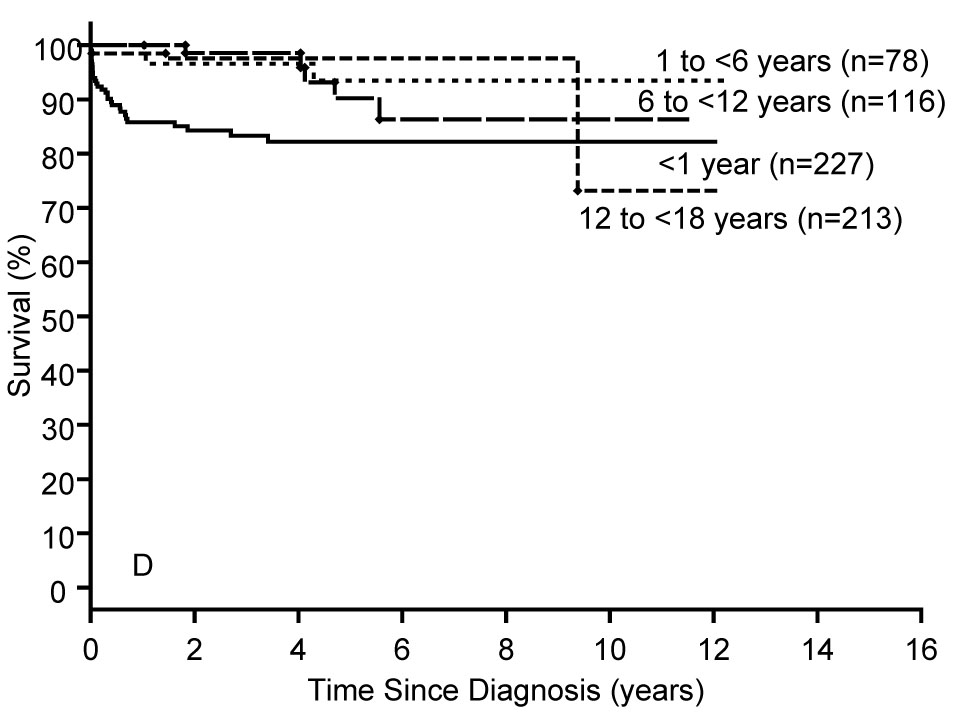

Clinical outcomes (death or heart transplantation) were reported based on an analysis of 849 patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.6 The causal subgroups were idiopathic (75%), malformation syndromes (9%), inborn errors of metabolism (9%), and neuromuscular disorders (8%). Survival was poorest in the patients with inborn errors of metabolism (Figure 3A) or malformation syndromes (Figure 3B). Survival was significantly lower for patients less than one year of age at diagnosis in the inborn errors of metabolism and idiopathic groups compared with those aged one year or older (Figure 3A, 3D). For the total cohort of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy cases, there was a large peak in mortality between 0–2 years of age with a smaller peak for patients aged 12–16 years. In conclusion, children diagnosed at less than one year of age have the poorest outcomes and the widest spectrum of etiologies. For children who survive beyond one year of age, the annual mortality rate (1%) is much lower than has been previously reported in children and is similar to results from adult studies.

Figure 3.

A–D: Survival rates by age at diagnosis from the diagnosis of pure hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in A) Inborn Errors of Metabolism (N=74, logrank P<0.001); B) Malformation Syndromes (N=77, logrank P=0.070); C) Neuromuscular Diseases (N=64, logrank P=0.224), and D) Idiopathic Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (N=634, logrank P<0.001),.

Recent Findings from the PCMR

PCMR investigators have recently reported findings in several areas. These reports have been in the form of peer-reviewed abstracts, and manuscripts describing these results are currently in preparation or under journal review. One analysis has shown that the mortality rate for children with Duchene’s muscular dystrophy is significantly lower than that for children with Becker’s muscular dystrophy, or children in a PCMR reference group diagnosed with myocarditis or idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy at age 10 years or older. Children with either form of muscular dystrophy were significantly less likely to receive anticongestive therapy and nearly half as likely to receive ACE inhibitors at the time of diagnosis compared with other dilated cardiomyopathy patients.

Results from two PCMR analyses will be presented at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions to be held in Orlando, Florida in early November, 2007. These include an analysis of the use of medical therapies and an examination of the association between usage rates and clinical guidelines for patients with dilated cardiomyopathy, as well as an analysis of risk factors for death in children with cardiomyopathy and Noonan’s syndrome. Analyses utilizing PCMR data are currently ongoing regarding children with myocarditis, sudden death in children with cardiomyopathy, children with restrictive cardiomyopathy, the parent-reported functional status of children with cardiomyopathy, and additional outcome analyses for pediatric hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients.

Current PCMR Research

The PCMR is funded by the NHLBI through 2010. Study aims for the current research cycle are shown in Table 3. The merger between the PCMR and Pediatric Heart Transplant Study Group (PHTS) database (Aim 1) has been completed and analyses are ongoing. The first set of PCMR-PHTS analyses address 1) the association of echocardiographic ascertained cardiac remodeling and post-transplant survival; 2) the impact of heart transplantation as an end-stage treatment for pediatric cardiomyopathy on survival; 3) clinical factors associated with UNOS status and outcomes after listing for heart transplantation for children with dilated cardiomyopathy; and 4) outcomes for children with cardiomyopathy listed as UNOS status 2 compared to comparable children who are not currently listed for transplant. A repeat merger is proposed in the final year of the current grant to increase the follow up data for the merged PCMR-PHTS patients. In order to address Aims 2–3, the PCMR is enrolling up to 400 pediatric cardiomyopathy patients from ten of the largest PCMR clinical sites in a cohort study. Current enrollment is 221 patients with enrollment through the end of 2008. The primary goal of this study is to estimate the association between clinical outcome, functional status, and genetic/viral status. The biologic specimens collected under the cohort study protocol are being tested for the prevalence of the G4.5 mutation8–10 among boys with cardiomyopathy (blood) and to assess viral status in all patients with myocarditis or other subgroups of cardiomyopathy (tissue). The PCMR has functional status data on over 250 pre-transplant cardiomyopathy patients. In addition to the proposed, cohort an additional 150 patients post-transplant PCMR patients are being recruited for a functional status substudy to increase the power of the pre- and post-transplant functional status comparisons described in the current specific aims.

Table 3.

Specific Aims of the Current PCMR Study: 2005–2010

| Specific Aim 1: | To integrate the PCMR and the Pediatric Heart Transplant Study Group (PHTS) databases in order to examine whether and how cardiac transplantation modifies the clinical course of cardiomyopathy in children. |

| Specific Aim 2: | Establish the longitudinal course of functional status in children with cardiomyopathy, and analyze the relationship to clinical events and outcomes. |

| Specific Aim 3: | Investigate how genetic and viral markers of cardiomyopathy are associated with clinical and functional outcomes. |

Conclusions

The PCMR is currently in the thirteenth year of funding by the NHLBI and contains detailed clinical information on over 3000 cases. Important discoveries to date include the estimation of incidence of pediatric cardiomyopathy in the United States, identification of predictors of clinical outcomes for children with dilated or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and factors associated with the establishment of etiology for pediatric cardiomyopathy. Results of analyses regarding children with myocarditis, restrictive cardiomyopathy, children with cardiomyopathy and muscular dystrophy or Noonan’s syndrome are being, or will soon be, reported. The current PCMR study is addressing the pre- and post-transplant clinical course, including functional status, for children with cardiomyopathy as well as the prevalence of specific genetic mutations or viral serology in this patient group. The PCMR is the largest and most complete multi-center prospective data resource regarding the etiology, clinical course and outcomes for children with cardiomyopathy.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (HL53392) and the Childrens Cardiomyopathy Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Grenier MA, Osganian SK, Cox GF, et al. Design and implementation of the North American Pediatric Cardiomyopathy Registry. American Heart Journal. 2000;139:S86–S95. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2000.103933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Towbin JA, Lowe AM, Colan SD, et al. Incidence, causes, and outcomes of dilated cardiomyopathy in children. Jama. 2006;296:1867–1876. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.15.1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lipshultz SE, Sleeper LA, Towbin JA, et al. The incidence of pediatric cardiomyopathy in two regions of the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1647–1655. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arola A, Jokinen E, Ruuskanen O, et al. Epidemiology of idiopathic cardiomyopathies in children and adolescents. A nationwide study in Finland. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146:385–393. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nugent AW, Daubeney PEF, Chondros P, et al. The epidemiology of childhood cardiomyopathy in Australia. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1639–1646. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colan SD, Lipshultz SE, Lowe AM, et al. Epidemiology and cause-specific outcome of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in children: findings from the Pediatric Cardiomyopathy Registry. Circulation. 2007;115:773–781. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.621185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cox GF, Sleeper LA, Lowe AM, et al. Factors associated with establishing a causal diagnosis for children with cardiomyopathy. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1519–1531. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelley RI, Cheatham JP, Clark BJ, et al. X-linked dilated cardiomyopathy with neutropenia, growth retardation, and 3-methylglutaconic aciduria. J Pediatr. 1991;119:738–747. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80289-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bione S, D'Adamo P, Maestrini E, Gedeon AK, Bolhuis PA, Toniolo D. A novel X-linked gene, G4.5, is responsible for Barth syndrome. Nat Genet. 1996;12:385–389. doi: 10.1038/ng0496-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schlame M, Towbin JA, Heerdt PM, Jehle R, DiMauro S, Blanck TJJ. Deficiency of tetralinoleoyl-cardiolipin in Barth syndrome. Ann Neurol. 2002;51:634–637. doi: 10.1002/ana.10176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]