Abstract

We previously showed that S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe) and its metabolite methylthioadenosine (MTA) blocked lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) expression in RAW (murine macrophage cell line) and Kupffer cells at the transcriptional level without affecting nuclear factor κ B nuclear binding. However, the exact molecular mechanism or mechanisms of the inhibitory effect were unclear. While SAMe is a methyl donor, MTA is an inhibitor of methylation. SAMe can convert to MTA spontaneously, so the effect of exogenous SAMe may be mediated by MTA. The aim of our current work is to examine whether the mechanism of SAMe and MTA’s inhibitory effect on proinflammatory mediators might involve modulation of histone methylation. In RAW cells, we found that LPS induced TNFα expression by both transcriptional and posttranscriptional mechanisms. SAMe and MTA treatment inhibited the LPS-induced increase in gene transcription. Using the chromatin immunoprecipitation assay, we found that LPS increased the binding of trimethylated histone 3 lysine 4 (H3K4) to the TNFα promoter, and this was completely blocked by either SAMe or MTA pretreatment. Similar effects were observed with LPS-mediated induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS). LPS increased the binding of histone methyltransferases Set1 and myeloid/lymphoid leukemia to these promoters, which was unaffected by SAMe or MTA. The effects of MTA in RAW cells were confirmed in vivo in LPS-treated mice. Exogenous SAMe is unstable and converts spontaneously to MTA, which is stable and cell-permeant. Treatment with SAMe doubled intracellular MTA and S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) levels. SAH also inhibited H3K4 binding to TNFα and iNOS promoters.

Conclusion

The mechanism of SAMe’s pharmacologic inhibitory effect on proinflammatory mediators is mainly mediated by MTA and SAH at the level of histone methylation.

S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe) is the principal methyl donor in biological reactions and a precursor for glutathione and polyamines.1 In the biosynthesis of polyamines from SAMe, methylthioadenosine (MTA) is generated as a byproduct.1 Hepatic deficiency of SAMe is a common metabolic abnormality in patients with liver disease, and its administration improves survival.1 Systemic exposure to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is frequently found in patients with liver cirrhosis, and it has an etiological role in liver injury.2 In mammals, LPS elicits the generation of numerous proinflammatory mediators, such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS).3,4 The modulation by SAMe of the inflammatory response triggered by LPS is a crucial part of its hepatoprotective effect. In this regard, SAMe has been shown to inhibit LPS-induced TNFα and iNOS expression at the transcriptional level in Kupffer cells, RAW 264.7 cells, a murine macrophage cell line, and rat liver,5-7 but the mechanisms underlying this inhibitory effect are not fully understood.

TNFα and iNOS gene expression is largely predicated by the binding of nuclear factor κ B (NFκB) to its cis regulatory elements within TNFα and iNOS promoters.8 Four κB sites have been identified in the murine TNFα promoter. These sites are termed κB1 to κB4 and are located at the nucleotide positions −860, −660, −630, and −510, respectively. Each of these sites mediates transcriptional activation by LPS, but κB2 and κB3 have a predominant role.9,10 As for iNOS regulation, two κB sites have been identified in the murine iNOS promoter, and they are located at the nucleotide positions −80 and −971, where the distal κB site is believed to be essential for iNOS production following various stimulations.11 In our previous work, we showed that SAMe’s inhibitory effect was not prevented by overexpression of p65 and/or its coactivator p300 or enhanced by overexpression of coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase 1, an enzyme that methylates p300 and inhibits a p65-p300 interaction.5 Moreover, MTA, which is not a methyl donor but rather a methylation reaction inhibitor,1 recapitulates the effect of SAMe, and this suggests that the inhibition is not due to the methyl donor capability of SAMe.5

Numerous studies have shown a clear link between the pattern of histone posttranslational modifications found in promoter regions and gene transcription, thus leading to the statement of the histone code hypothesis,12 which postulates that the pattern of histone modifications in a locus considerably extends the amount of information conveyed by the genomic code. Histone H3 and H4 hyperacetylation in promoter regions is closely correlated with gene activation.13 Interestingly, NFκB has been shown to interact with the histone deacetylase (HDAC) corepressors HDAC1 and HDAC2 to negatively regulate gene expression.14 Moreover, we have shown that both SAMe and MTA induce the recruitment of HDAC1 and HDAC2 to the human betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase (BHMT) promoter region containing the κB sites,15 suggesting a role for SAMe and MTA in the histone posttranslational modification. Unlike acetylation, histone H3 methylation can be equally associated with either transcriptional activation or repression. Methylation of the lysine residue Lys4 of histone H3 (H3K4)13 correlates with activation of gene expression,16 whereas H3 Lys9 (H3K9) methylation is involved in the establishment and maintenance of silent heterochromatin regions.17 Moreover, lysine residues can be monomethylated, dimethylated, or trimethylated in vivo, with the trimethylated H3K4 form being most positively correlated with transcriptional activation.16 It appears that this modification is associated with RNA polymerase II loading in promoter regions.18 Multiple human methyltransferases target H3K4, including Set1, myeloid/lymphoid leukemia (MLL), and Set7/9, although Set1 and MLL are the only ones able to trimethylate H3K4.16,19,20 These findings, along with the recent identification of retinol binding protein 2 (RBP2) and Smcy homolog X-linked (SMCX), the first trimethyl-H3K4 –specific demethylases,21,22 suggest that methylation is subjected to dynamic regulation by a higher turnover rate than initially thought.

MTA has been shown to effectively block methylation of H3K4 in different cell lines.23,24 In several studies, its ability to decrease the H3K4 methylation was correlated with attenuation of gene expression.25,26 In contrast to MTA, which is a very stable molecule, its precursor SAMe is highly unstable and can be converted to MTA spontaneously and also via the polyamine pathway,27,28 and this suggests that the effect of exogenous SAMe may be mediated by MTA. In the present study, we examined whether the mechanism of SAMe’s inhibitory effect might involve modulation of histone modifications and whether this might be mediated via MTA.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Reagents

RAW 264.7 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). LPS (Escherichia coli 055:B5), MTA, and S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). SAMe in the form of dried disulfate p-toluenesulfonate powder was generously provided by Gnosis SRL (Cairate, Italy). All other reagents were analytical-grade and were obtained from commercial sources.

Cell Treatment Conditions

RAW cells were pretreated in serum-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium with 0.75 mM SAMe, 0.5 mM MTA, or 1 mM SAH for 16 hours unless otherwise mentioned. They were then stimulated with LPS (500 ng/mL) or an equal volume of solvent (water) for 4 hours. At these concentrations of SAMe, SAH, or MTA and with durations of treatment up to 20 hours in the current study, no toxicity was evident (not shown).

Animal Experiments

Male C57BL6 mice (weighing 19-21 g) were injected with LPS (15 mg/kg) intraperitoneally or with phosphate buffered saline as a vehicle control. Where indicated, a single dose of 96 μmol/kg MTA dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; 50 μL/mouse) was administrated intraperitoneally 30 minutes before LPS injection. Control mice received only DMSO intraperitoneally. Six hours later, mice were sacrificed, and liver tissues were removed, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until analysis. Animals were treated humanely, and all procedures were in compliance with our institutional guidelines for the use of laboratory animals.

Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Analysis

Total RNA isolated from cells and livers as described5 was subjected to reverse transcription with M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). One microliter of the reverse-transcription product was subjected to quantitative real-time PCR analysis. The primers and TaqMan probes for TNFα, iNOS, Set1, MLL, Rbp2, and Smcx and Universal PCR master mix were purchased from ABI (Foster City, CA). 18S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) was used as housekeeping genes as described.5 The ΔCt value obtained was used to find the relative expression of TNFα, iNOS, Set1, MLL, Rbp2, and Smcx genes according to the following formula: relative expression =2−ΔΔCt, where ΔΔCt is equal to ΔCt of those genes in treated cells minus ΔCt of the same genes in control cells.

Transient Transfection Assay

The mouse TNFα promoter-firefly luciferase construct (designated TNFα-luc) has been described previously.5 Jun2-luciferase (Jun2-luc; known to be transactivated by ATF2/Jun) and TRE-luciferase (TRE-luc; known to be transactivated by c-Jun/c-Fos) constructs were kindly provided by Dr. Z. Ronai.29 For transient transfection assays, 1.5 × 105 RAW cells were plated in 12-well dishes and transfected with 2 μg of TNFα promoter, Jun2-luc, TRE-luc, or control pGL3 basic for 2 hours with Targefect-Raw (Targeting System, San Diego, CA). To control transfection efficiency, cells were cotransfected with 20 ng of Renilla phRL-TK vector from Promega. Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were measured with the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega).

Determination of SAMe, MTA, and SAH Levels

RAW cells were grown at a density of 4 × 106 cells in 100-mm dishes and treated with SAMe (0.75-2 mM) or MTA (0.5-2 mM). Cellular and extracellular SAMe, MTA, and SAH levels were measured by high-performance liquid chromatography as described.28

Nuclear Protein Extraction and Western Blot Analysis

Nuclear extracts were prepared as described30 and resolved by electrophoresis on 7%-12% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel. Western blotting was performed following standard protocols (Amersham Bio-Sciences, Piscataway, NJ) using primary antibodies for Set1 (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX), Rbp2 (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX), HDAC1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA), and MLL (Upstate, Waltham, MA).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay

ChIP assays were carried out according to the ChIP assay kit protocol provided by Upstate with antibodies against monomethyl-H3K4, dimethyl-H3K4, and trimethyl-H3K4, MLL (Upstate), H3 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), Set1 (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX), p50-NF-κB, p65-NF-κB, c-fos, c-jun, early growth response 1 (Egr-1), HDAC1, HDAC2, and Sv40-T-Ag (simian virus 40 large antigen; (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies). PCR of the TNFα promoter region across two relevant NF-κB sites10 within −849 to −622 was performed with the forward primer 5′-TGAAAGGAGAAGGCTTGTGAG-3′ (bp −849 to −828; all sequences are relative to the ATG start codon) and the reverse primer 5′-CTTCTGAAAGCTGGGTGCAT-3′ (bp −602 to −622). PCR of the TNFα promoter region across Egr-1 and activator protein 1 (AP-1) sites31 was performed with the forward primer 5′-GGGGGAGAGATTCCTTGATG-3′ (bp −384 to −364) and the reverse primer 5′-CTCATTCAACCCTCGGAAAA-3′ (bp −245 to −225). PCR of the iNOS promoter across one relevant NF-κB site11 within −972 to −753 was performed with the forward primer 5′-GGGGATTTTCCCTCCTCTG-3′ (bp −972 to −952) and the reverse primer 5′-GAGTTTGGGCTAGCCTGGTC-3′ (bp −773 to −753). As a control, PCR of the glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) promoter (−2058 to −1834) was performed with the forward primer 5′-GTGGCACAGACAACTTCCTG-3′ (bp −2058 to −2038) and the reverse primer 5′-CTGATTACGAGGGGTGGAAG-3′ (bp −1854 to −1834). All PCR products were run on 2% (wt/vol) agarose gels prestained with ethidium bromide.

Statistical Analysis

Data are given as the mean ± the standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analysis was performed with analysis of variance followed by Fisher’s test for multiple comparisons. Significance was defined by P < 0.05.

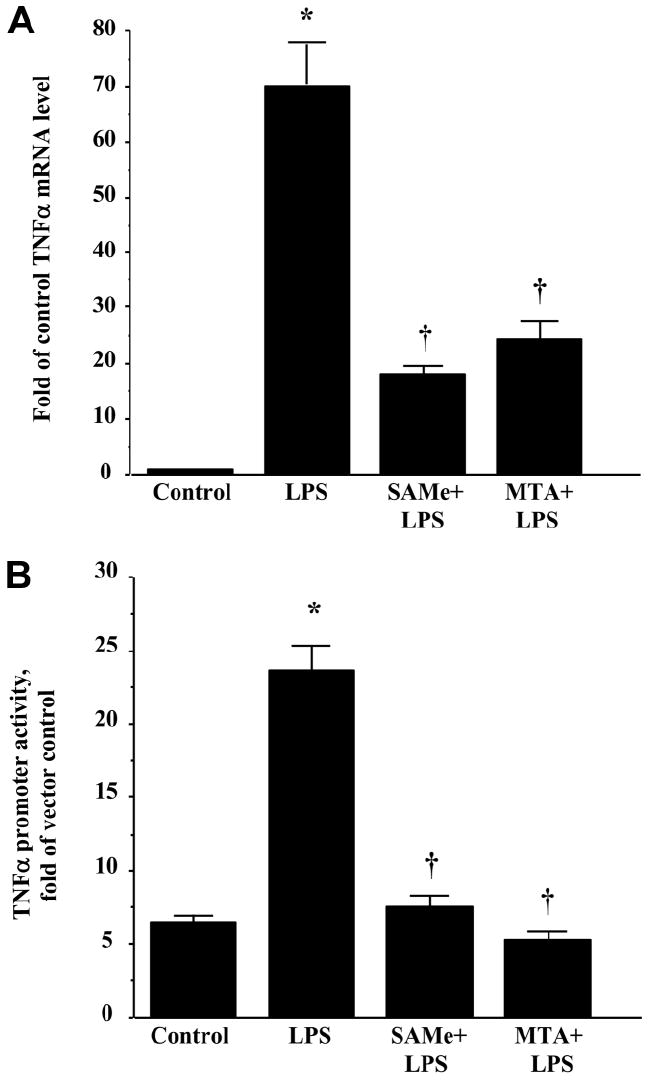

Effects of SAMe and MTA on LPS-Stimulated TNFα Expression

Stimulation of RAW cells with LPS (500 ng/mL) for 4 hours markedly increased the TNFα messenger RNA (mRNA) level. Pretreatment with either SAMe (0.75mM) or MTA (0.5mM) for 16 hours partially inhibited the increase in the TNFα mRNA level (Fig. 1A). LPS stimulation increased the TNFα promoter activity by approximately 4-fold in comparison with the control. Either SAMe or MTA pretreatment completely prevented LPS-mediated induction of promoter activity (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Effects of SAMe and MTA on LPS-stimulated TNFα expression. (A) SAMe and MTA reduced an LPS-induced increase in TNFα mRNA levels. RAW cells were pretreated with 0.75 mM SAMe or 0.5 mM MTA for 16 hours and then stimulated with LPS (500 ng/mL) or vehicle (water) for 4 hours. RNA was extracted and subjected to quantitative real-time PCR analysis with a TNFα TaqMan probe with 18S rRNA for housekeeping. Results are expressed as fold over control cells (mean ± SEM) from three independent experiments performed in duplicate. *P < 0.001 versus control; †P < 0.05 versus control and LPS. (B) SAMe and MTA completely blocked LPS-induced TNFα promoter activity. RAW cells were transiently transfected with 2 μg of TNFα promoter-luciferase plasmid and 20 ng of Renilla phRL-TK with Targefect-Raw. SAMe (0.75 mM) or MTA (0.5 mM) pretreatment started 24 hours after the addition of the vectors for 16 hours. Then, LPS (500 ng/mL) or vehicle (water) was added for 4 hours. Cell lysates were collected for luciferase assay. Levels of TNFα-luc promoter were normalized by transfection efficiency as determined by Renilla luciferase activity. Results are expressed as fold over vector control (mean ± SEM) from three independent experiments performed in triplicate. *P < 0.001 versus control; †P < 0.001 versus control and LPS.

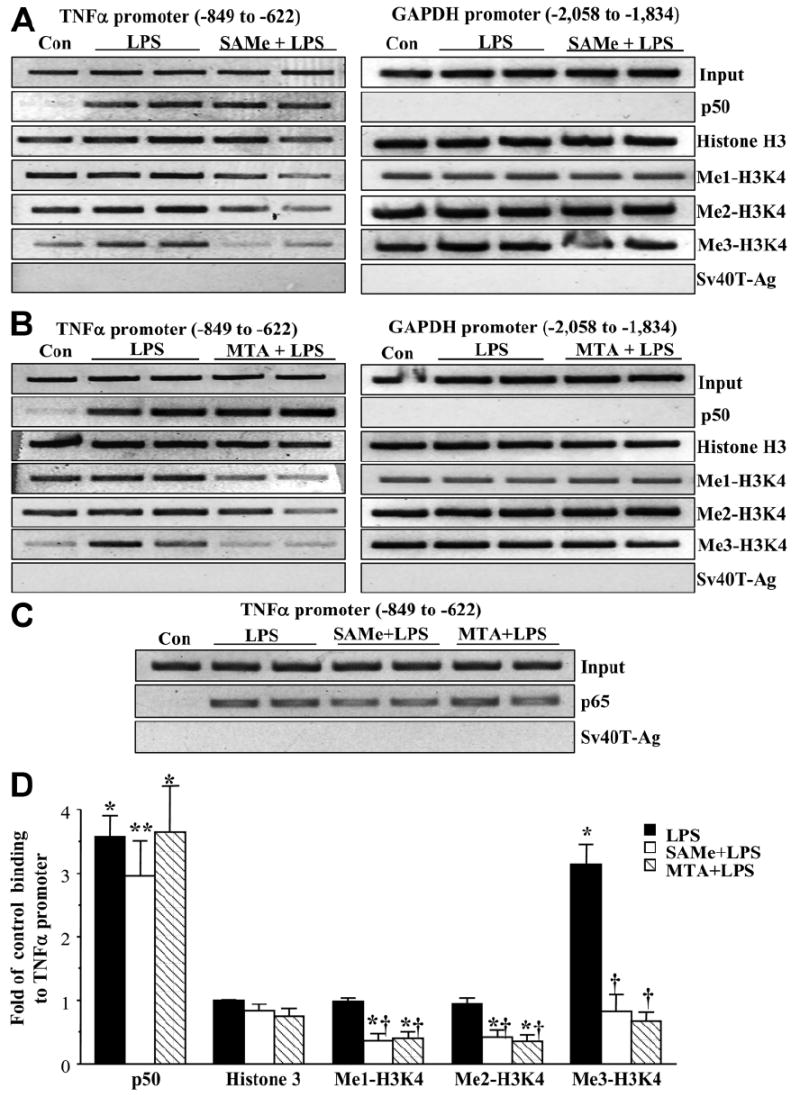

SAMe and MTA Lower the Binding of Methylated H3K4 to the TNFα Promoter

To further investigate the mechanism(s) of SAMe and MTA’s inhibitory effect on LPS-stimulated TNFα transcription, we performed ChIP analysis to detect the levels of various proteins bound to the TNFα promoter containing two key κB sites (Fig. 2). LPS treatment induced the binding of the NFκB subunits p50 and p65 to the TNFα promoter. Pretreatment with either SAMe or MTA did not prevent the increase in p50 or p65 binding, and this was consistent with previous results from electrophoretic mobility-shift assay with supershifting.5 Binding of trimethylated H3K4 correlates with activation of gene expression in most systems.16 Consistent with this, LPS treatment induced the binding of trimethyl-H3K4, but not the monomethylated or dimethylated forms, to the TNFα promoter (Fig. 2). Pretreatment with either SAMe or MTA lowered the binding of monomethylated and dimethylated H3K4 in comparison with the baseline and prevented the LPS-induced binding of trimethylated H3K4. Treatment with SAMe or MTA did not alter the binding of HDACs to the TNFα promoter (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

(A) SAMe and (B) MTA lower the binding of methylated H3K4 to the TNFα promoter. [A,B (left) and C] RAW cells were pretreated with 0.75 mM SAMe or 0.5 mM MTA for 16 hours and then stimulated with LPS (500 ng/mL) or vehicle (water) for 4 hours, and the ChIP assay was used to assess the binding of p50, p65, histone H3, and the three methylated forms of H3K4 (Me1-H3K4, Me2-H3K4, and Me3-H3K4) to the kB sites within the −849 to −622 region of the murine TNFα promoter in an endogenous chromatin configuration as described in the Materials and Methods section. Input genomic DNA (Input) was used as a loading control, and immunoprecipitation with an antibody against Sv40-Ag was used as a negative control. [A,B (right)] PCR products from the amplification of a κB site–free region within −2058 to −1834 of the murine GAPDH promoter were used as specificity controls. (D) Densitometry was performed. Results were normalized to the input and expressed as fold of control binding to TNFα promoter (mean ± SEM) from three to seven independent experiments. *P < 0.01 versus control; **P < 0.05 versus control; †P < 0.01 versus LPS.

In addition to NFκB, AP-1 and Egr-1 have also been shown to be important for the transcriptional activation of TNFα.31 To see if SAMe or MTA affects LPS-induced binding of these transcription factors to the TNFα promoter, ChIP analysis was performed, covering the region (−384 to −225) that contains these sites. Figure 3A shows that LPS induced the binding of c-Jun, c-Fos, and Egr-1, and this was not affected by SAMe or MTA. However, SAMe and MTA prevented the LPS-induced binding of trimethyl-H3K4 to this region. To see if this translated into an inhibitory effect on AP-1–dependent transcriptional activity, we evaluated the effect of SAMe or MTA on luciferase activity driven by Jun2 and TRE promoter constructs. LPS treatment induced the promoter activity of both Jun2 and TRE promoter constructs, and this was prevented completely by either SAMe or MTA (Fig. 3B,C).

Fig. 3.

(A) SAMe and MTA lower the binding of methylated H3K4 to the TNFα promoter region containing AP-1 and Egr-1 sites. RAW cells were pretreated with 0.75 mM SAMe or 0.5 mM MTA for 16 hours and then stimulated with LPS (500 ng/mL) or vehicle (water) for 4 hours, and the ChIP assay was used to assess the binding of c-Fos, c-Jun, Egr-1, and the trimethylated form of H3K4 (Me3-H3K4) to the AP-1 and Egr-1 sites within the −384 to −225 region of the murine TNFα promoter in an endogenous chromatin configuration as described in the Materials and Methods section. Input genomic DNA (Input) was used as a loading control, and immunoprecipitation with an antibody against Sv40-Ag was used as a negative control. (B,C) SAMe and MTA completely blocked LPS-induced AP-1 transcriptional activity. RAW cells were transiently transfected with 2 μg of (B) Jun2-luc or (C) TRE-luc plasmids and 20 ng of Renilla phRL-TK with Targefect-Raw. SAMe (0.75 mM) or MTA (0.5 mM) pretreatment was started 24 hours after the addition of the vectors for 16 hours. Then, LPS (500 ng/mL) or vehicle (water) was added for another 4 hours. Cell lysates were collected for luciferase assay. Levels of Jun2-luc or TRE-luc were normalized by transfection efficiency as determined by Renilla luciferase activity. Results are expressed as fold over control (mean ± SEM) from triplicates. *P < 0.005 versus control, SAMe + LPS, and MTA + LPS.

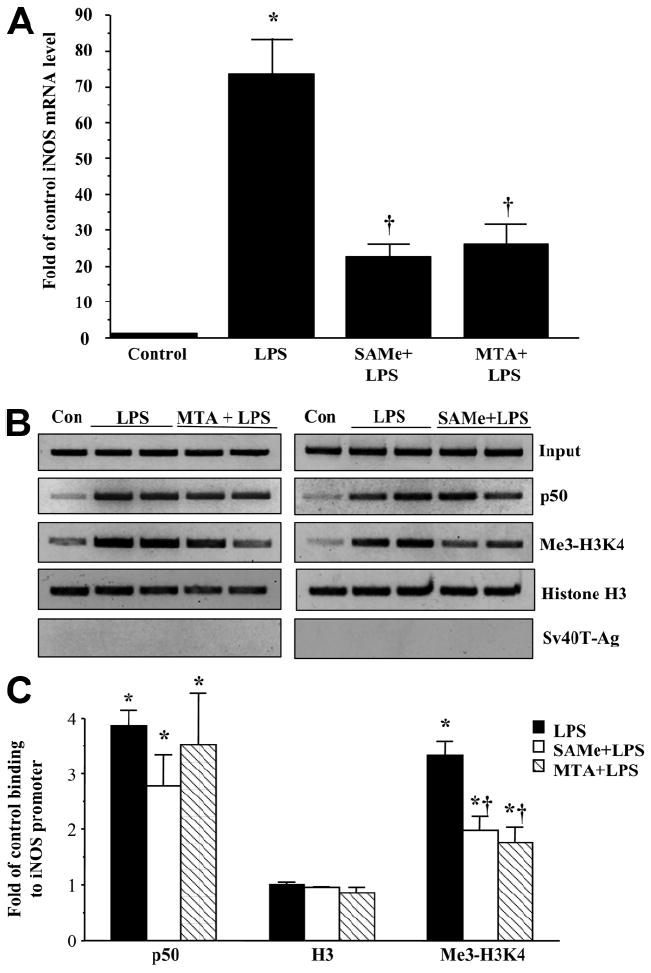

SAMe and MTA Inhibit LPS-Induced iNOS Expression and Binding of Trimethylated H3K4 to the iNOS Promoter

We next examined whether SAMe and MTA could exert a similar effect on iNOS, which is known to be induced by LPS at the promoter level, and the induction can be blocked by SAMe.6 Stimulation of RAW cells with LPS markedly increased the iNOS mRNA level as expected (Fig. 4A). Pretreatment with either SAMe or MTA partially inhibited the increase in the iNOS mRNA level (Fig. 4A). Importantly, we found that LPS treatment induced the binding of trimethylated H3K4 to the iNOS promoter (Fig. 4B,C), and pretreatment with either SAMe or MTA reduced this binding.

Fig. 4.

(A) SAMe and MTA reduced an LPS-induced increase in iNOS mRNA levels. RAW cells were pretreated with 0.75 mM SAMe or 0.5 mM MTA for 16 hours and then stimulated with LPS (500 ng/mL) or vehicle (water) for 4 hours. RNA was extracted and subjected to quantitative real-time PCR analysis with an iNOS TaqMan probe with 18S rRNA for housekeeping. Results are expressed as fold over control cells (mean ± SEM) from four independent experiments performed in duplicate. *P < 0.001 versus control; †P < 0.05 versus control and LPS. (B) MTA (left panel) and SAMe (right panel) lowered the binding of trimethylated H3K4 (Me3-H3K4) to the iNOS promoter. RAW cells were pretreated with 0.75 mM SAMe or 0.5 mM MTA for 16 hours and then stimulated with LPS (500 ng/mL) or vehicle (water) for 4 hours, and the ChIP assay was used to assess the binding of p50, histone H3, and Me3-H3K4 to the kB site within the −972 to −753 region of the murine iNOS promoter in an endogenous chromatin configuration as described in the Materials and Methods section. Input genomic DNA (Input) was used as a loading control, and immunoprecipitation with an antibody against Sv40-Ag was used as a negative control. (C) Densitometry was performed. Results were normalized to the input and expressed as fold of control binding to the iNOS promoter (mean ± SEM) from three to seven independent experiments. *P < 0.01 versus control; †P < 0.05 versus LPS.

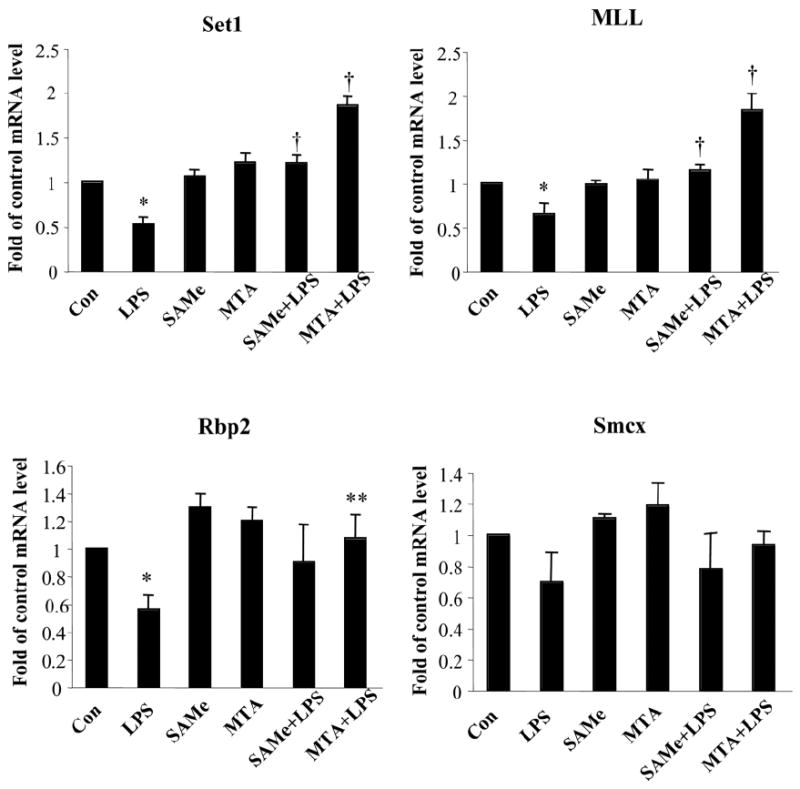

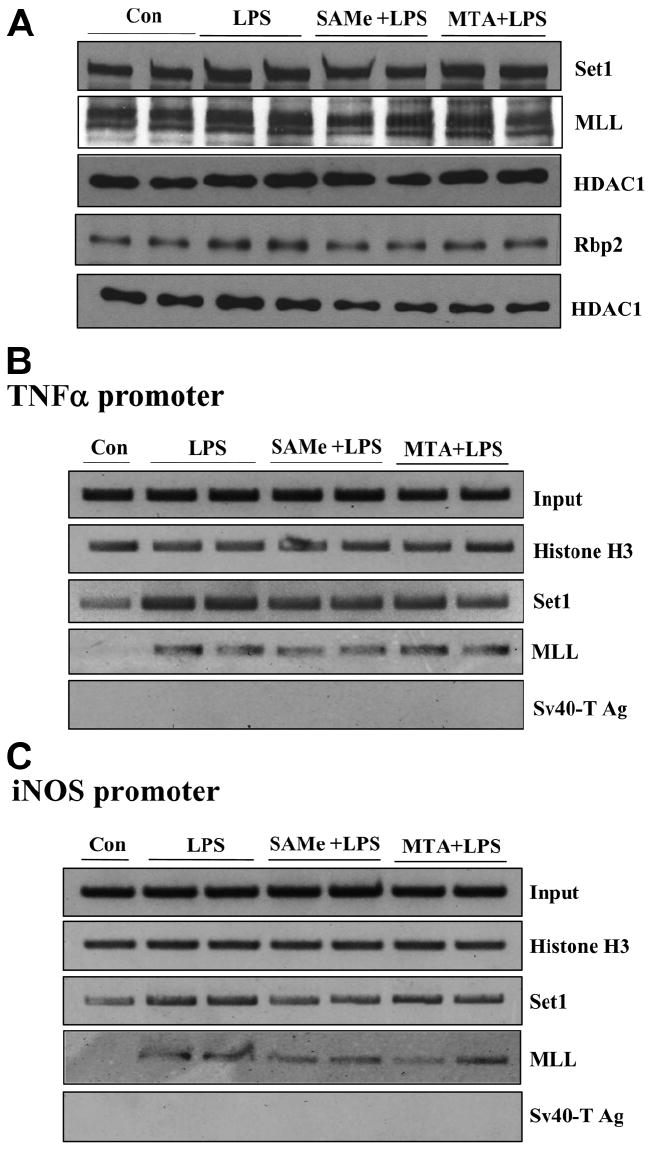

Effect of LPS, SAMe, and MTA on the Expression of Histone Methyltransferases and Demethylases

To examine if a reduction in the binding of methylated histones was due to either a reduction in the expression of histone methyltransferases known to methylate H3K4 or an increase in the expression of histone demethylases known to demethylate trimethylated H3K4, we examined the effect of these treatments on the expression of Set1 and MLL methyltransferases and on the expression of Rbp2 and Smcx demethylases (Fig. 5). Surprisingly, we found that LPS treatment significantly reduced the mRNA levels of Set1, MLL, and Rbp2. Pretreatment with either SAMe or MTA prevented the fall, and MTA in particular even increased the mRNA levels of Set1 and MLL more than 50% above baseline. We next examined whether changes in mRNA levels translated to a similar change in protein levels. Figure 6A shows the effect of the same treatments on the nuclear protein levels of Set1, MLL, and Rbp2, and despite a 50% fall in the mRNA levels of Set1, MLL, and Rbp2 after LPS treatment, protein levels were unchanged. SAMe and MTA also had no influence on the protein levels of Set1, MLL, and Rbp2.

Fig. 5.

Effect of LPS, SAMe, and MTA on expression of histone methyltransferases and demethylases. RAW cells were pretreated with 0.75 mM SAMe or 0.5 mM MTA for 16 hours and then stimulated with LPS (500 ng/mL) or vehicle (water) for 4 hours. RNA was extracted and subjected to quantitative real-time PCR analysis with Set1, MLL, Rbp2, and Smcx Taq-Man probes with 18S rRNA for housekeeping. Results are expressed as fold over control cells (mean ± SEM) from four to seven independent experiments performed in duplicate. *P < 0.01 versus control; †P < 0.05 versus control and LPS; **P < 0.05 versus LPS.

Fig. 6.

(A) Effect of the LPS, SAMe, and MTA treatments on the nuclear protein levels of Set1, MLL, and Rbp2. RAW cells were pretreated with 0.75 mM SAMe or 0.5 mM MTA for 16 hours and then stimulated with LPS (500 ng/mL) or vehicle (water) for 4 hours. Nuclear extracts (5-30 μg) were loaded onto 7%-10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by western blotting against Set1, MLL, Rbp2, or HDAC1. (B,C) Effect of LPS, SAMe, and MTA on the binding of Set1 and MLL to (B) TNFα and (C) iNOS promoters. RAW cells were pretreated with 0.75 mM SAMe or 0.5 mM MTA for 16 hours and then stimulated with LPS (500 ng/mL) or vehicle (water) for 4 hours, and the ChIP assay was used to assess the binding of histone H3, Set1, and MLL (B) to the kB sites within the −849 to −622 region of the murine TNFα promoter and (C) to the kB site within the −972 to −753 region of the murine iNOS promoter. Representative ChIP assays from three independent experiments are shown.

Effect of LPS, SAMe, and MTA on the Binding of Set1 and MLL to the TNFα and iNOS Promoters

Set1 and MLL are the H3K4-specific methyltransferases capable of trimethylating H3K4.16,19,20 To see if these histone methyltransferases are recruited to the TNFα and iNOS promoters following LPS treatment, we performed ChIP analysis following LPS treatment. As shown in Fig. 6B,C, LPS treatment resulted in an increase in the binding of Set1 and MLL to the TNFα and iNOS promoters. Neither SAMe nor MTA pretreatment prevented this increase in binding.

Effect of SAMe and MTA on Intracellular and Extracellular SAMe, SAH, and MTA Levels

MTA has been shown to block methylation of H3K4 in a number of systems.23-25,27 In contrast to MTA, which is a very stable molecule, its precursor SAMe is highly unstable and can be converted to MTA spontaneously and also via the polyamine pathway27,28; this suggests that the effect of exogenous SAMe may be mediated by MTA. It is also known that MTA inhibits SAH hydrolase,32 the enzyme responsible for metabolizing SAH, and SAH itself is a strong inhibitor of almost all SAMe-dependent methyltransferases.33 In fact, some have speculated that MTA acts more as an indirect inhibitor of methyltransferases by raising the SAH level.27 Table 1 shows the effects of various treatments on SAMe, SAH, and MTA levels. LPS treatment had no influence on the level of any of these metabolites. SAMe and MTA treatments raised the intracellular levels of SAMe, MTA, and SAH in a dose-dependent manner. MTA can raise the SAMe level because of the presence of the methionine salvage pathway.27 At the doses used for the aforementioned studies (0.75 mM SAMe and 0.5 mM MTA), SAMe raised the level of all three metabolites significantly, but MTA did not raise the SAMe level, and its effect on the SAH level was not significant. Note that the intracellular levels of MTA were similar after treatment with SAMe or MTA. In extracellular culture media, after 20 hours of treatment, only 37% of the original SAMe remained; some (27%) was converted to MTA. In contrast, 82% to 88% of MTA remained.

Table 1.

Effects of Various Treatments on SAMe, SAH, and MTA Levels in RAW Cells

| ID | SAMe | SAH | MTA | SAH/SAMe Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intracellular levels | ||||

| Control | 1.45 ± 0.28 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 0.24 ± 0.05 | 0.12 ± 0.03 |

| LPS | 1.46 ± 0.19 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.25 ± 0.05 | 0.07 ± 0.02 |

| 0.75 mM SAMe + LPS | 3.52 ± 0.78* | 0.26 ± 0.05* | 0.49 ± 0.11* | 0.10 ± 0.04 |

| 1 mM SAMe + LPS | 4.77 ± 0.71† | 0.42 ± 0.11* | 0.52 ± 0.08* | 0.10 ± 0.05 |

| 2 mM SAMe + LPS | 7.45 ± 1.14† | 0.72 ± 0.11† | 0.72 ± 0.22* | 0.12 ± 0.04 |

| 0.5 mM MTA + LPS | 1.90 ± 0.35 | 0.21 ± 0.06 | 0.45 ± 0.05* | 0.12 ± 0.05 |

| 1 mM MTA + LPS | 2.13 ± 0.42 | 0.35 ± 0.12* | 0.61 ± 0.05* | 0.19 ± 0.08 |

| 2 mM MTA + LPS | 5.18 ± 1.58* | 1.36 ± 0.79* | 1.62 ± 0.35* | 0.53 ± 0.20* |

| Extracellular levels (culture media) | ||||

| Control | 0.014 ± 0.002 | 0.0002 | 0.0008 ± 0.001 | |

| LPS | 0.013 ± 0.003 | 0.0002 | 0.0009 ± 0.001 | |

| 0.75 mM SAMe + LPS | 0.275 ± 0.032† | 0.203 ± 0.031† | ||

| 1 mM SAMe + LPS | 0.375 ± 0.056† | 0.0059 | 0.277 ± 0.240† | |

| 2 mM SAMe + LPS | 0.726 ± 0.070† | 0.552 ± 0.061† | ||

| 0.5 mM MTA + LPS | 0.014 ± 0.002 | 0.405 ± 0.041† | ||

| 1 mM MTA + LPS | 0.013 ± 0.003 | 0.0002 | 0.875 ± 0.082† | |

| 2 mM MTA + LPS | 0.014 ± 0.002 | 1.72 ± 0.072† |

The units for all metabolites are nanomoles per milligram of protein in the intracellular compartment and millimoles per liter in the culture media. Results represent mean ± SEM values from 6 to 9 experiments. Cells were pretreated with SAMe or MTA for 16 hours followed by LPS for 4 hours.

P < 0.05 versus the respective controls.

P < 0.001 versus the respective controls.

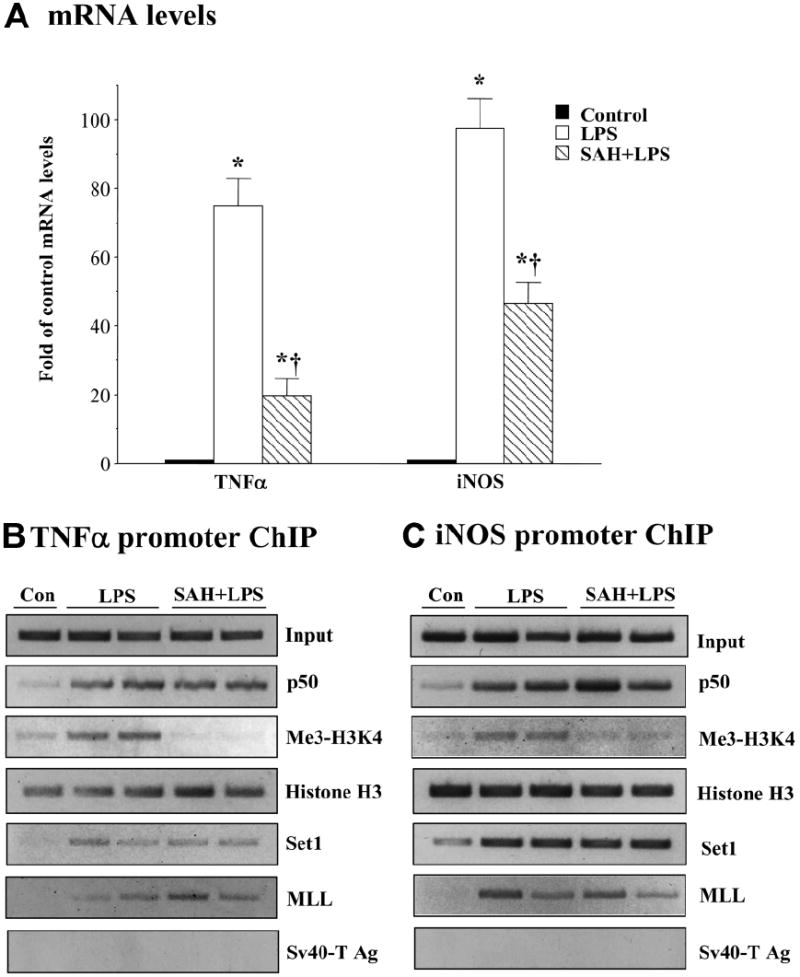

SAH Recapitulates the Inhibitory Actions of SAMe and MTA

Because SAMe treatment raised the SAH level, we next examined whether SAH could recapitulate the effects of SAMe and MTA on TNFα and iNOS. Similar to SAMe and MTA, SAH pretreatment significantly inhibited the ability of LPS to increase TNF and iNOS mRNA levels (Fig. 7A). Moreover, this effect was also correlated with a reduction of trimethylated H3K4 binding to both TNFα and iNOS promoters. Similar to SAMe and MTA, SAH pretreatment did not prevent Set1 or MLL binding to these promoters (Fig. 7B,C).

Fig. 7.

SAH recapitulates the inhibitory actions of SAMe and MTA. RAW cells were pretreated with 1 mM SAH for 16 hours and then stimulated with LPS (500 ng/mL) or vehicle (water) for 4 hours. (A) RNA was extracted and subjected to quantitative real-time PCR analysis with TNFα or iNOS TaqMan probes with 18S rRNA for housekeeping. Results are expressed as fold over control cells (mean ± SEM) from four independent experiments performed in duplicate. *P < 0.001 versus control; †P < 0.001 versus LPS. (B,C) ChIP assay was used to assess the binding of p50, trimethyl-H3K4 (Me3-H3K4), histone H3, Set1, and MLL (B) to the kB sites within the −849 to −622 region of the murine TNFα promoter and (C) to the kB site within the −972 to −753 region of the murine iNOS promoter. Representative ChIP assays from three independent experiments are shown.

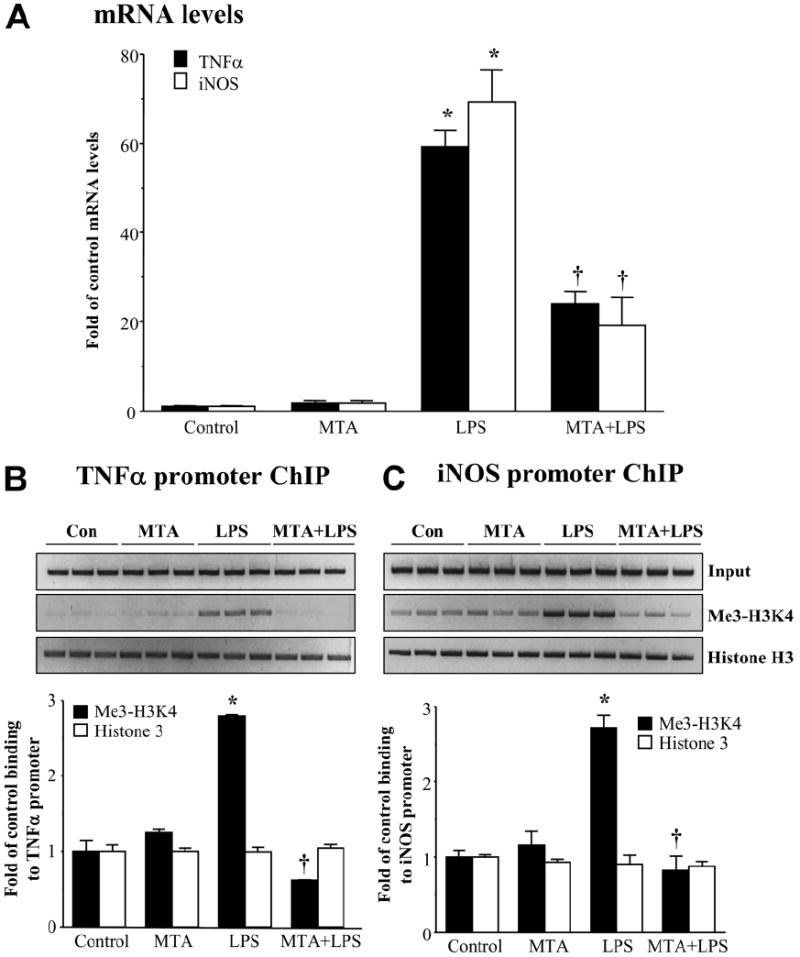

Effect of MTA In Vivo

Although MTA has been shown to inhibit H3K4 methylation,23-25 none of the work investigated whether this could happen in vivo. We had previously shown that MTA could block LPS-induced lethality in mice.34 To see if MTA could exert similar changes in vivo, we examined MTA’s effect on an LPS-induced increase in TNFα and iNOS expression and binding of trimethylated H3K4 to these promoters. LPS injection markedly increased hepatic TNFα and iNOS mRNA levels after 6 hours. Pretreatment with MTA for 30 minutes partially inhibited the increase in TNFα and iNOS mRNA levels (Fig. 8A), with very similar magnitudes as observed in RAW cells (Figs. 1 and 4). Importantly, LPS injection induced the binding of trimethylated H3K4 to TNFα and iNOS promoters, and pretreatment with MTA completely prevented this binding (Fig. 8B,C).

Fig. 8.

MTA inhibits LPS-induced TNFα and iNOS expression and binding of trimethylated H3K4 in vivo. Mice were pretreated with MTA or vehicle, and this was followed by LPS treatment for 6 hours; hepatic TNFα and iNOS mRNA levels and the binding of trimethylated H3K4 to these promoters were examined as described in the Materials and Methods section. (A) RNA was extracted and subjected to quantitative real-time PCR analysis with TNFα or iNOS TaqMan probes with 18S rRNA for housekeeping. Results are expressed as fold over control animals (mean ± SEM) from three animals per group. *P < 0.005 versus control; †P < 0.05 versus control and LPS. (B,C) ChIP assay was used to assess the binding of trim-ethyl-H3K4 (Me3-H3K4) and histone H3 (B) to the kB sites within the −849 to −622 region of the murine TNFα promoter and (C) to the kB site within the −972 to −753 region of the murine iNOS promoter. Densitometry results are summarized below respective ChIPs. Results are expressed as fold of control binding to the TNFα or iNOS promoter (mean ± SEM) from three animals per group. *P < 0.0005 versus control; †P < 0.001 versus LPS.

Discussion

Administration of SAMe in different experimental models of liver injury has been shown to attenuate tissue damage and improve survival in patients.1,35 An inflammatory component is a common denominator to many of the hepatotoxic conditions in which SAMe alleviates liver injury,1,5-7 and there is increasing evidence that the modulation of such an inflammatory response could be a key mechanism of SAMe’s beneficial effect. TNFα is an early-released cytokine recognized as a central mediator of endotoxemia and systemic inflammation.3 Another important player in systemic inflammation is iNOS; its increased expression is followed by massive NO production, a systemic response implicated in the lethality of sepsis.36 We and others previously demonstrated the inhibitory effect of SAMe on LPS-stimulated TNFα and iNOS expression in RAW cells.5-7 Here we confirm that SAMe or MTA pretreatment completely prevented LPS-mediated induction of TNFα promoter activity. However, SAMe or MTA treatment did not completely prevent an LPS-induced increase in TNFα mRNA, and this suggests that both increased transcription and mRNA stabilization contributed to the increase in the TNFα mRNA level and that these treatments inhibited the increase in transcription only.

In our previous work, we showed that SAMe’s inhibitory effect was not prevented by overexpression of p65 and/or its coactivator p300 or enhanced by overexpression of coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase 1. Moreover, MTA, which is not a methyl donor but rather a methylation reaction inhibitor,27 recapitulated the effect of SAMe, and this suggests that the inhibition was not due to the methyl donor capability of SAMe.5 We previously showed that both SAMe and MTA induced the recruitment of HDACs to the human BHMT promoter,15 and this prompted us to examine histone posttranslational modifications in the TNFα and iNOS promoters. We first examined HDAC binding to these promoters and found that SAMe or MTA treatment did not alter HDAC binding. We next examined the methylation of H3K4 because several publications suggest that MTA can inhibit methylation of H3K425,26 and there is increasing speculation that exogenous SAMe works via MTA, at least when it is methyl donor–independent.27,28 Here we show that LPS increases the binding of trimethylated H3K4 to the TNFα and iNOS promoters containing NFκB, AP-1, and Egr-1 sites, and this is blocked by either SAMe or MTA pretreatment. H3K4 trimethylation is a hallmark of transcriptional activation,18 and our results are consistent with the notion that SAMe and MTA inhibited the increase in transcription by blocking the increase in trimethylated H3K4 binding. However, we did not find the binding of monomethylated or dimethylated H3K4 to TNFα and iNOS promoters to correlate with the activation of the expression, and this is also in agreement with previous data.16 We found that SAMe or MTA treatment reduced promoter H3K4 monomethylation and dimethylation (Fig. 2), and this indicates that these agents might play a role in reducing, at the promoter level, the substrate for trimethylation of H3K4 upon LPS treatment.

Set1 and MLL have been shown to trimethylate H3K4.16,19,20 This prompted us to check the expression of these enzymes after treatments with LPS, SAMe, and MTA. Surprisingly, we found that mRNA levels of both Set1 and MLL were reduced after treatment with LPS, and pretreatment with either SAMe or MTA prevented the fall or even increased these mRNA levels. However, the protein levels of Set1 and MLL were unchanged. Remarkably, we also found that LPS reduced the expression of Rbp2, which was recently described as a trimethyl-H3K4–specific demethylase,21 and MTA pretreatment recovered it to the normal levels; this suggests that the regulation of Rbp2 expression by LPS and MTA could also account for the dynamics of trimethylation of H3K4 found in TNFα and iNOS promoters upon these treatments. However, despite dramatic changes in mRNA levels, protein levels of these genes were unaffected, at least for the duration of our experimental protocol. Importantly, we show that LPS increased the binding of histone methyltransferases Set1 and MLL to these promoters, which was unaffected by SAMe or MTA. The recruitment of these regulators of H3K4 methylation to DNA has been recently reported.37 In their work, Narayanan and colleagues37 showed that the trimethylation of H3K4 bound to DNA depends on the binding of Set1 and MLL.

In dissecting mechanisms underlying the inhibitory effect of SAMe and MTA on binding of methylation of H3K4 to the TNFα and iNOS promoters, it is important to remark that treatment with SAMe or MTA doubles intracellular MTA levels, and this suggests that SAMe’s inhibitory effect is mediated by MTA. However, MTA is known to inhibit SAH hydrolase,32 the enzyme responsible for metabolizing SAH, and SAH itself is a strong inhibitor of almost all SAMe-dependent methyltransferases.33 In fact, MTA may act more as an indirect inhibitor of methyltransferases by raising the SAH level.27 Indeed, we found increased SAH levels upon MTA treatment in a dose-dependent fashion (Table 1). However, at the dose of MTA used for most of the experiments (0.5 mM), it did not have a statistically significant effect on the intracellular SAH level, and this raises the possibility that MTA may work directly also. Interestingly, others have shown that several inhibitors of SAH hydrolase also inhibit LPS-induced TNFα expression.38 These observations led us to examine the effect of SAH on LPS-induced TNFα and iNOS expression. Similar to SAMe and MTA, SAH pretreatment significantly inhibited the ability of LPS to increase TNFα and iNOS mRNA levels. Importantly, this effect also correlated with a reduction of trimethylated H3K4 binding to both TNFα and iNOS promoters. The SAH level must be kept in check because many methyltransferases have a higher affinity for SAH than SAMe, and this makes SAH a potent inhibitor of many methylation reactions.33 Assuming that this is also true for Set1 and MLL methyltransferases, we speculate that SAMe treatment could lead to the inhibition of Set1 and MLL-mediated H3K4 methylation through MTA and SAH accumulation.

Although MTA has been shown to inhibit H3K4 methylation in various cell types,23-25 whether it exerts a similar effect in vivo was unknown. Here we demonstrate that MTA completely recapitulated its effects in RAW cells in vivo by blocking LPS-induced hepatic expression of proinflammatory mediators and binding of trimethyl-H3K4 to these promoters.

In summary, we have uncovered a novel mechanism for SAMe-mediated attenuation of proinflammatory responses via inhibition of trimethylated H3K4 binding to the promoter region of TNFα and iNOS. This aspect of SAMe has not been described previously and is important in understanding its therapeutic effect.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant DK51719 (to S.C.L.), National Institutes of Health grants AA12677, AA13847, and AT1576 (to S.C.L. and J.M.M.), Plan Nacional of I+D SAF 2005-00855, and HEPADIP-EULSHM-CT-205 (to J.M.M.). RAW cells were provided by the Cell Culture Core of the University of Southern California Research Center for Liver Diseases (DK48522). A.I.A. is a recipient of the postdoctoral fellowship supported by the Centro de Investigación Cooperativa en Biosciencías, and K.R. is a recipient of the postdoctoral fellowship of the Training Program in Alcoholic Liver and Pancreatic Diseases (T32 AA07578).

Abbreviations

- AP-1

activator protein 1

- BHMT

betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- EGR-1

early growth response 1

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- H3K4

histone 3 lysine 4

- H3K9

histone 3 lysine 9

- HDAC

histone deacetylase

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- Jun2-luc

Jun2-luciferase

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MLL

myeloid/lymphoid leukemia

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- MTA

methylthioadenosine

- NFκB

nuclear factor κ B

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- RAW 264.7

murine macrophage cell line

- RBP2

retinol binding protein 2

- rRNA

ribosomal RNA

- SAH

S-adenosylhomocysteine

- SAMe

S-adenosylmethionine

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- SMCX

Smcy homolog X-linked

- Sv40-T-Ag

simian virus 40 large antigen

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor α

- TRE-luc

TRE-luciferase

Footnotes

Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com).

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

References

- 1.Mato JM, Lu SC. Role of S-adenosyl-L-methionine in liver health and injury. HEPATOLOGY. 2007;45:1306–1312. doi: 10.1002/hep.21650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Su GL. Lipopolysaccharides in liver injury: molecular mechanisms of Kupffer cell activation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;283:G256–G265. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00550.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tracey KJ, Cerami A. Tumor necrosis factor: a pleiotropic cytokine and therapeutic target. Annu Rev Med. 1994;45:491–503. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.45.1.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li J, Billiar TR. Nitric oxide. IV. Determinants of nitric oxide protection and toxicity in liver. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:G1069–G1073. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.5.G1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veal N, Hsieh CL, Xiong S, Mato JM, Lu S, Tsukamoto H. Inhibition of lipopolysaccharide-stimulated TNF-alpha promoter activity by S-adenosylmethionine and 5′-methylthioadenosine. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287:G352–G362. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00316.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Majano PL, García-Monzón C, García-Trevijano ER, Corrales FJ, Cámara J, Ortiz P, et al. S-adenosylmethionine modulates inducible nitric oxide synthase gene expression in rat liver and isolated hepatocytes. J Hepatol. 2001;35:692–699. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00208-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watson WH, Zhao Y, Chawla RK. S-adenosylmethionine attenuates the lipopolysaccharide-induced expression of the gene for tumour necrosis factor alpha. Biochem J. 1999;342:21–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shakhov AN, Collart MA, Vassalli P, Nedospasov SA, Jongeneel CV. Kappa B-type enhancers are involved in lipopolysaccharide-mediated transcriptional activation of the tumor necrosis factor alpha gene in primary macrophages. J Exp Med. 1990;171:35–47. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collart MA, Baeuerle P, Vassalli P. Regulation of tumor necrosis factor alpha transcription in macrophages: involvement of four kappa B-like motifs and of constitutive and inducible forms of NF-kappa B. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:1498–1506. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.4.1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drouet C, Shakhov AN, Jongeneel CV. Enhancers and transcription factors controlling the inducibility of the tumor necrosis factor-alpha promoter in primary macrophages. J Immunol. 1991;147:1694–1700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim YM, Lee BS, Yi KY, Paik SG. Upstream NF-kappaB site is required for the maximal expression of mouse inducible nitric oxide synthase gene in interferon-gamma plus lipopolysaccharide-induced RAW 264.7 macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;236:655–660. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jenuwein T, Allis CD. Translating the histone code. Science. 2001;293:1074–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1063127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurdistani SK, Tavazoie S, Grunstein M. Mapping global histone acetylation patterns to gene expression. Cell. 2004;117:721–733. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ashburner BP, Westerheide SD, Baldwin AS., Jr The p65 (RelA) subunit of NF-kappaB interacts with the histone deacetylase (HDAC) corepressors HDAC1 and HDAC2 to negatively regulate gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:7065–7077. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.20.7065-7077.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ou X, Yang H, Ramani K, Ara AI, Chen H, Mato JM, et al. Inhibition of human betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase expression by S-adenosylmethionine and methylthioadenosine. Biochem J. 2007;401:87–96. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santos-Rosa H, Schneider R, Bannister AJ, Sherriff J, Bernstein BE, Emre NC, et al. Active genes are tri-methylated at K4 of histone H3. Nature. 2002;419:407–411. doi: 10.1038/nature01080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lachner M, O’Carroll D, Rea S, Mechtler K, Jenuwein T. Methylation of histone H3 lysine 9 creates a binding site for HP1 proteins. Nature. 2001;410:116–120. doi: 10.1038/35065132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guenther MG, Levine SS, Boyer LA, Jaenisch R, Young RA. A chromatin landmark and transcription initiation at most promoters in human cells. Cell. 2007;130:77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang H, Cao R, Xia L, Erdjument-Bromage H, Borchers C, Tempst P, et al. Purification and functional characterization of a histone H3-lysine 4-specific methyltransferase. Mol Cell. 2001;8:1207–1217. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00405-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guenther MG, Jenner RG, Chevalier B, Nakamura T, Croce CM, Canaani E, et al. Global and Hox-specific roles for the MLL1 methyltranssferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:8603–8608. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503072102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klose RJ, Yan Q, Tothova Z, Yamane K, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, et al. The retinoblastoma binding protein RBP2 is an H3K4 demethylase. Cell. 2007;128:889–900. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iwase S, Lan F, Bayliss P, de la Torre-Ubieta L, Huarte M, Qi HH, et al. The X-linked mental retardation gene SMCX/JARID1C defines a family of histone H3 lysine 4 demethylases. Cell. 2007;128:1077–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song MR, Ghosh A. FGF2-induced chromatin remodeling regulates CNTF-mediated gene expression and astrocyte differentiation. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:229–235. doi: 10.1038/nn1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chau CM, Lieberman PM. Dynamic chromatin boundaries delineate a latency control region of Epstein-Barr virus. J Virol. 2004;78:12308–12319. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.22.12308-12319.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fish JE, Matouk CC, Rachlis A, Lin S, Tai SC, D’Abreo C, et al. The expression of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase is controlled by a cell-specific histone code. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:24824–24838. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502115200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Musri MM, Corominola H, Casamitjana R, Gomis R, Parrizas M. Histone H3 lysine 4 dimethylation signals the transcriptional competence of the adiponectin promoter in preadipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17180–17188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601295200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clarke SG. Inhibition of mammalian protein methyltransferases by 5′-methylthioadenosine (MTA): a mechanism of action of dietary SAMe? Enzymes. 2006;24:467–493. doi: 10.1016/S1874-6047(06)80018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen H, Xia M, Lin M, Yang H, Kuhlenkamp J, Li T, et al. Role of methionine adenosyltransferase 2A and S-adenosylmethionine in mitogen-induced growth of human colon cancer cells. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:207–218. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhoumik A, Huang TG, Ivanov V, Gangi L, Qiao RF, Woo SL, et al. An ATF2-derived peptide sensitizes melanomas to apoptosis and inhibits their growth and metastasis. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:643–650. doi: 10.1172/JCI16081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dignam JD, Lebovitz RM, Roeder R. Accurate transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:1475–1489. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.5.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barthel R, Tsytsykova AV, Barczak AK, Tsai EY, Dascher CC, Brenner MB, et al. Regulation of tumor necrosis factor alpha gene expression by mycobacteria involves the assembly of a unique enhanceosome dependent on the coactivator proteins CBP/p300. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:526–533. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.2.526-533.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferro AJ, Vandenbark AA, MacDonald MR. Inactivation of S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase by 5′-deoxy-5′-methylthioadenosine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1981;100:523–531. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(81)80208-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clarke S, Banfield K. S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferases: potential targets in homocysteine-linked pathology. In: Carmel R, Jacobsen D, editors. Homocysteine in Health and Disease. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hevia H, Varela-Rey M, Corrales FJ, Berasain C, Martínez-Chantar ML, Latasa MU, et al. 5′-Methylthioadenosine modulates the inflammatory response to endotoxin in mice and in rat hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2004;39:1088–1098. doi: 10.1002/hep.20154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mato JM, Camara J, Fernandez de Paz J, Caballeria L, Coll S, Caballero A, et al. S-adenosylmethionine in alcoholic liver cirrhosis: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicenter clinical trial. J Hepatol. 1999;30:1081–1089. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80263-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.MacMicking JD, Nathan C, Hom G, Chartrain N, Fletcher DS, Trumbauer M, et al. Altered responses to bacterial infection and endotoxic shock in mice lacking inducible nitric oxide synthase Cell. 1995;81:641–650. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90085-3. published correction appears in Cell 1995;81:1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Narayanan A, Ruyechan WT, Kristie TM. The coactivator host cell factor-1 mediates Set1 and MLL1 H3K4 trimethylation at herpesvirus immediate early promoters for initiation of infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:10835–10840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704351104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jeong SY, Lee JH, Kim HS, Hong SH, Cheong CH, Kim IK. 3-Deazaa-denosine analogues inhibit the production of tumour necrosis factor-alpha in RAW264.7 cells stimulated with lipopolysaccharide. Immunology. 1996;89:558–562. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.d01-781.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]