Abstract

Purpose/Objectives

To explore Korean American women’s symbolic meanings related to their breasts and cervix, to examine attitudes and beliefs about breast and cervical cancer, and to find relationships between the participants’ beliefs and their cancer screening behaviors.

Research Approach

Descriptive, qualitative analysis.

Setting

Southwestern United States.

Participants

33 Korean-born women at least 40 years of age.

Methodologic Approach

In-depth, face-to-face, individual interviews were conducted in Korean. A semistructured interview guide was used to ensure comparable core content across all interviews. Transcribed and translated interviews were analyzed using descriptive content analysis.

Main Research Variables

Breast cancer, cervical cancer, cancer screening, beliefs, and Korean American women.

Findings

Korean American women’s symbolic meaning of their breasts and cervix are closely related to their past experiences of bearing and rearing children. Negative life experiences among older Korean American women contributed to negative perceptions about cervical cancer. Having information about cancer, either correct or incorrect, and having faith in God or destiny may be barriers to obtaining screening tests.

Conclusions

Korean American women’s symbolic meanings regarding their breasts and cervix, as well as their beliefs about breast cancer and cervical cancer and cancer screening, are associated with their cultural and interpersonal contexts. Their beliefs or limited knowledge appear to relate to their screening behaviors.

Interpretation

Interventions that carefully address Korean American women’s beliefs about breast cancer and cervical cancer as well as associated symbolic meanings may increase their cancer screening behaviors. Clinicians should consider Korean American women’s culture-specific beliefs and representations as well as their life experiences in providing care for the population.

Key Points.

Korean American women’s symbolic meanings with regard to their breasts and cervix are almost all related to their interpersonal relationships with their family members, either children or husbands.

Among older Korean American women, negative past experiences in their lives, such as having abortions or having husbands with promiscuous lifestyles, contributed to negative perceptions about the cervix and cervical cancer.

Korean American women’s beliefs about breast and cervical cancer appeared to have influenced many of them to believe that they are not at risk for breast or cervical cancer as long as they stay healthy eat a healthy diet, do not have a family history of cancer, do not think or worry about it, and have not had multiple sexual partners or abortions.

Clinicians should consider Korean American women’s beliefs about breast and cervical cancer as well as associated symbolic meanings of their breasts and cervix in providing care for the population.

Korean American women’s age-adjusted cervical cancer incidence rate (15.2 per 100,000) is more than double that of non-Hispanic white women in the United States (7.5 per 100,000), and their incidence rate also is higher than the average rate for all Asian American women (11.8 per 100,000) (Miller et al., 1996). Additionally, among Korean American women aged 55–69 years, the rate of invasive cervical cancer is much higher than that for Hispanic or African American women (Miller et al.).

Breast cancer is the most commonly occurring cancer in Korean American women. In Los Angeles County, CA, the rate for Korean American women almost doubled from 1988 (26.1 per 100,000) to 1997 (44.5 per 100,000) compared to a 1%–2% increase in the rates for non-Hispanic white and Hispanic women and a marginal decrease in the rate for African American women during the same period (Deapen, Liu, Perkins, Bernstein, & Ross, 2002). The rising incidence of breast cancer among Korean women is projected to continue as the length of time they live in the United States increases because of their adaptation to Western lifestyles (Deapen et al.; Ursin et al., 1999).

Research with Korean American women consistently has reported relatively low rates of breast and cervical cancer screening, which indicates that the population may be at relatively high risk for cancer mortality and morbidity because of delayed diagnosis. Studies have reported that only 22%–75% of Korean American women had ever had a Papanicolaou (Pap) test, and only 26%–63% had had the test in the prior two to three years (Juon, Choi, & Kim, 2000; Juon, Seung-Lee, & Klassen, 2003; Kim et al., 1999; Moskavitz, Kazinets, Tager, & Wong, 2004; Sarna, Tae, Kim, Brecht, & Maxwell, 2001; Wismer et al., 1998b). Their Pap screening rates are far lower than the age-adjusted rates from a national random sample, the 1999 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), which found that 94% of women aged 18 years and older with an intact cervix had ever had a Pap test and 84% had had one in the prior three years (Coughlin, Uhler, Hall, & Briss, 2004).

Regarding breast cancer screening, 48%–78% of Korean American women had ever had a mammogram and 34%–61% were estimated to have had a mammogram in the prior two years (Juon et al., 2000; Juon, Kim, Shankar, & Han, 2004; Lee, Fogg, & Sadler, 2006; Moskavitz et al., 2004; Wismer et al., 1998a). The rates are far lower than those from the 1999 BRFSS, which revealed that 87% of women in the United States aged 40 years and older had ever had a mammogram and 75% of the women had had a mammogram in the prior two years (Coughlin et al., 2004).

Symbolic meanings of the body are essentially related to a person’s experiences and perceptions of health, illness, and health care (Good, 1994; Lupton, 2000). The meaning of the body evolves from a person’s daily lived experiences, constantly revised and transformed in social and cultural contexts, which constitutes a person’s ideas and beliefs about health and illness (Good; Lupton). Korean American women may attribute unique meanings to body parts in their social and cultural contexts. This may be the case especially with sexual organs such as their breasts and cervix; in traditional Korean culture, sexuality, especially in women, is associated with taboos (Im & Meleis, 2000; Im, Park, Lee, & Yun, 2004). Therefore, Korean American women’s symbolic meanings of their bodies, particularly their breasts and cervix, may influence their beliefs about cancer in those body parts as well as their cancer screening behaviors.

Individuals’ beliefs about the cause and significance of a particular illness are interconnected with their healthcare-seeking behaviors (Kleinman, 1980; Kleinman & Seeman, 2000). According to Kleinman’s Illness Narratives Model, beliefs associated with an illness also tend to be linked with culturally influenced psychological and social characteristics. Therefore, Korean American women’s relatively low cancer screening rates could be a result, in part, of the symbolic meanings they attribute to their breasts and cervix and culture-specific beliefs and attitudes about breast cancer and cervical cancer. Healthcare providers should examine the women’s culture-specific beliefs to target health education more effectively. Therefore, the aims of this study were to explore Korean American women’s symbolic meanings of their breasts and cervix, examine attitudes and beliefs about breast cancer and cervical cancer, and find relationships between the participants’ beliefs and their cancer screening behaviors.

Methods

Descriptive, qualitative analysis of the phenomena was used for the study (Sandelowski, 2000). The approach was used to elicit Korean American women’s subjective perceptions of breast cancer and cervical cancer in their own language without the investigators’ interpretation or conceptualization of the data. This also was done to accurately describe participants’ symbolic meanings of their breasts and cervix.

Sample Recruitment

Through a qualitative, descriptive design, a purposive sample of 33 Korean American women aged 40 years and older was recruited for individual, in-depth interviews. Purposive sampling using the maximum variation strategy (Kuzel, 1992; Patton, 1990) was used in an attempt to tap known variables associated with rates of breast and cervical cancer screening, such as age, education, socioeconomic status, marital status, insurance status, and years in the United States. To be eligible for inclusion in the sample, subjects had to be Korean-born women living in San Diego County, CA, and be at least 40 years old.

The institutional review boards (IRBs) from the University of San Diego and the University of California, San Diego, approved the study methods, and participants were recruited from both university settings. Of the 33 participants, 24 were recruited through Korean American churches, Korean American physicians, and senior housing with a snowball sampling method. The remaining nine women were recruited from a larger study examining breast cancer screening behaviors among Asian American women (Sadler, Nguyen, Doan, Au, & Thomas, 1998). The nine Korean American women initially were recruited at Asian grocery stores (Sadler, Ryujin, Ko, & Nguyen, 2001). Using an IRB-approved protocol, bilingual Korean American research assistants contacted potential subjects and invited them to participate. The names of those who consented to being contacted were passed along for follow-up and recruitment into the current study.

Procedure

Once a prospective subject agreed to participate, the study protocol was explained and an appointment was set up for the investigator to meet with the prospective subject to conduct the full consent procedure and the interview. The interviews took place wherever the subjects preferred, with 18 interviews done in informants’ homes (55%), 11 in coffee shops (33%), and 4 in churches (12%). After a written consent form was signed by a prospective subject, a semistructured interview was conducted, lasting 30–60 minutes. All of the interviews were conducted in Korean because that was the stated preference of each of the subjects. Each woman who participated in an individual interview was compensated with $25 at the end of the session.

Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim in Korean onto computer disks by a person who specializes in typing Korean. The accuracy of the transcriptions was checked by the first author. The transcripts then were translated into English by a professional translator who is fluent in English and Korean. The transcripts then were checked by the primary author; when a disagreement occurred between the two, they discussed it until consensus was reached.

Interview Guidelines

The open-ended questions used for the interviews were, “What comes to your mind when you think of breasts?” “The cervix/uterus?” “Breast cancer?” “Cervical cancer?” Additional probes were used to follow up on leads in greater depth. At the beginning of the study, the researchers learned that most of the Korean women did not know the anatomic differences between cervix and uterus, probably because the Korean word for cervix (Ja-Gung-Kyung-Bu) and uterus (Ja-Gung) are similar. Therefore, in the study, cervix and uterus were used interchangeably when Korean American women were asked about their perceptions of the cervix. In English, Ja-Gung means uterus and Kyung-Bu means “entrance site.”

Data Analysis

The interview data were coded using standard, descriptive, qualitative content analysis (Miles & Huberman, 1994), and the transcribed data were entered into NVivo (QSR International). The coding systems were modified in the course of data analysis to ensure the best fit to the data to maximize description and minimize interpretation of the phenomena (Sandelowski, 2000). The coded documents then were analyzed using NVivo’s Boolean intersection function; participants’ cancer screening behaviors—whether they had had a mammogram in the prior year or a Pap test in the prior three years—were compared by their perceptions and beliefs.

To address the rigor of the study, responses were recorded and transcribed verbatim. The primary author first analyzed the data by identifying and categorizing codes for subjects’ responses to each question. Then the secondary author, who is an expert in qualitative research, independently assigned codes to subjects’ responses. The two authors’ codes were compared to assess inter-rater reliability. In areas where the two did not agree, definitions were clarified, and discussions continued until consensus was reached (Miles & Huberman, 1994). Member checking was done by asking respondents to verify preliminary findings from the earlier interviews (Creswell, 1998). Methodologic and analytic audit trails were established by the first author, with review by and concurrence of the coauthor (Rodgers & Cowles, 1993). The researchers ensured depth of content and authenticity by thoroughly identifying diverse and novel data (Sandelowski & Barroso, 2002).

Findings

Sample Description

A summary of participants’ demographic characteristics is shown in Table 1. The participants’ mean age was 56.7 years (SD = 12.8, range = 40–85). The average woman had graduated from high school (X̄ = 12.5 years, SD = 4.5, range = 3–20) and had been living in the United States for 16 years (SD = 8.1, range = 3–32). Most of the subjects were married (73%) and Protestant (82%). Nearly three-fourths of the subjects had health insurance. However, for some of those who had private health insurance, it covered only life-threatening and major illnesses but not routine checkups and cancer screening. Those women likely would not have qualified for California’s mammography screening program for low-income women, although the study did not verify financial eligibility.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Health-Related Characteristics of Sample of Korean American Women

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Education (years) | ||

| 1–6 | 7 | 21 |

| 7–12 | 8 | 24 |

| 13–16 | 16 | 49 |

| Post-college | 2 | 6 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 24 | 73 |

| Widowed | 7 | 21 |

| Divorced | 2 | 6 |

| Type of insurance | ||

| Private | 12 | 36 |

| Public | 12 | 36 |

| None | 9 | 27 |

| Religion | ||

| Protestant | 27 | 82 |

| Catholic | 2 | 6 |

| No religion | 4 | 12 |

| Buddhist | – | – |

| Mammography done in the prior year | ||

| Yes | 21 | 64 |

| No | 12 | 36 |

| Pap test done in the prior three years | ||

| Yes | 24 | 73 |

| No | 8 | 24 |

| Missing data | 1 | 3 |

N = 33

Note. Because of rounding, percentages may not total 100.

Perceptions About Their Breasts and Cervix

Women in the study appeared to be very aware of a cultural prohibition against openly discussing breasts or the cervix. Many said they had never thought about the meanings of the terms. Several women discussed the traditional Korean taboo regarding using the word breast and how breasts usually are spoken of in a modest way. One woman who had studied Korean literature during her undergraduate years pointed out that the Korean word for breasts could be either You-bang, or Ab-gasum. The literal meaning of You-bang in Korean is “milk room,” and Ab-gasum means “front chest.” She said this indicates the way Korean culture influences the labeling of the body part to be more indirect and modest. Several participants also identified the cultural practice of describing breasts in indirect and modest ways (e.g., the Korean word for breast milk means mother’s milk). In the same context, in the Korean culture, it is shameful to emphasize the breasts or even to have big breasts, according to two older women. They said they used to wear traditional clothing that was tight around their front chests, flattening their breasts to avoid public display.

Considering that Korean words for breast are related to mothering, the researchers were not surprised to find that, to most participants, the meaning of their breasts and cervix or uterus related to their childbearing and childrearing experiences. Twelve women, for example, described breasts as instruments for breastfeeding. Some women were proud of their ability to breastfeed their babies, whereas those who said they had been unable to breastfeed their babies expressed feelings of guilt.

Several women also related the cervix or uterus to their children. Seven women expressed positive feelings about the cervix or uterus because it is the place babies come from, which makes them feel that it symbolizes womanhood. Two women identified the birthing experience as justification for why the cervix is more important than the breasts. One woman said it is a mystical area, and another described the cervix as where new life begins.

God gave us the uterus. … So many things happen there. It is where a couple’s lovemaking takes place, it produces monthly periods, and it is where my children were. I think it’s even a magical place. The whole thing about it fascinates me. Sometimes I smile to myself when I think about the wonders of the uterus.

Older women were more likely than younger women to express some negative feelings about the cervix. To them, the cervix reminded them of a body part that had to be kept clean because of their husbands’ promiscuous sexual lives. One woman thought about the cervix in terms of cleanliness because of her husband’s uncircumcised penis. She said, “If a man hasn’t been circumcised, his [penis] is very dirty with fungus because the foreskin covers the [head of the penis] area.” For several women, the cervix reminded them of the painful or unpleasant experience of having an abortion when they were young and alternative family-planning methods were not readily available.

Beliefs About Breast Cancer, Cervical Cancer, and Screening Behaviors

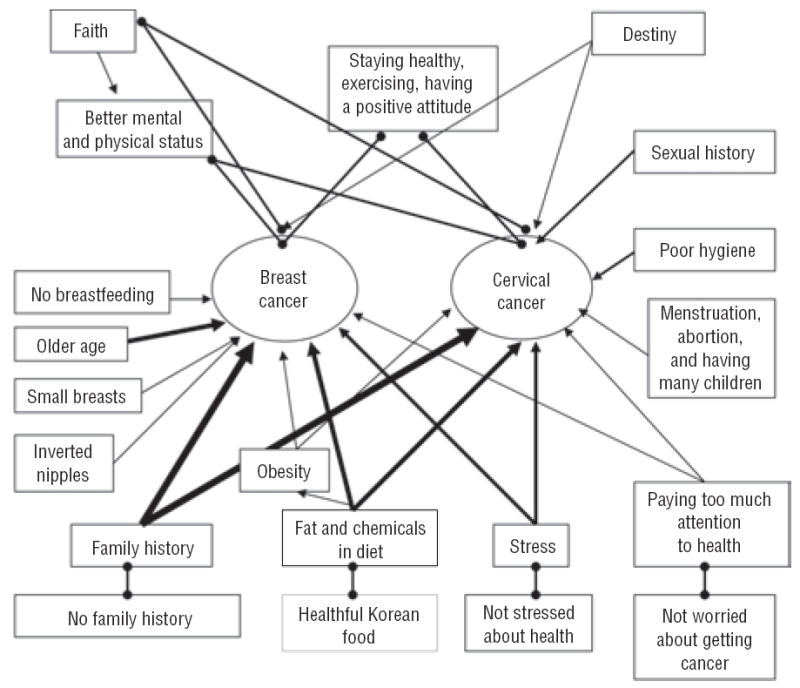

The results of the data analysis of interviews to comprehensively describe the participants’ beliefs about breast cancer and cervical cancer are diagrammed in Figure 1. The figure includes a set of nodes and arrows. The nodes represent important beliefs among Korean American women regarding breast cancer and cervical cancer, and the arrows indicate the causal relationships among these beliefs. The width of an arrow indicates the proportional number of participants who stated the belief represented by a node. The lines with rounded ends indicate the participants’ beliefs about what can protect or prevent them from getting breast cancer or cervical cancer. Pertinent relationships between the participants’ beliefs and their cancer screening behaviors (measured as those who had had a mammogram during the prior 12 months and those who had not) are summarized in Table 2. No distinct pattern was found between the participants’ beliefs and their cervical cancer screening behaviors.

Figure 1. Conceptual Model of Korean American Women’s Beliefs About Breast Cancer and Cervical Cancer.

Note. Nodes represent important beliefs among Korean American women regarding breast and cervical cancer; arrows indicate the causal relationships among beliefs. The width of an arrow indicates the proportional number of participants who stated the belief represented by a node. The lines with rounded ends indicate the participants’ beliefs about what can protect or prevent them from getting breast and cervical cancer.

Table 2.

Relationships Between the Participants’ Beliefs and Cancer Screening Behaviors

| Current Mammogram (N = 21)

|

No Current Mammogram (N = 12)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belief | n | % | n | % |

| Family history | 7 | 33 | 7 | 58 |

| Diet | 4 | 19 | 6 | 50 |

| Stress | 1 | 5 | 5 | 42 |

| Age | 4 | 19 | 5 | 42 |

Korean American women in the study mentioned a family history of cancer, improper diet, and stress as major causes of breast and cervical cancer. Women who had such beliefs were less likely to have had mammography within the year than those who did not mention such beliefs. Nearly half of the women (n = 14) indicated that a family history of cancer was a major risk for breast or cervical cancer. Among them, six believed that a family history was related to any kind of cancer, four believed it was related only to breast cancer, and the remaining four believed it was related only to cervical cancer. More than half of the women who did not have an up-to-date mammogram believed that having a family history is related to cancer, compared with only one-third of women who had an up-to-date mammogram. Their belief appeared to lead them to conclude that insofar as they did not have any family history, they were not susceptible to breast or cervical cancer. Of the 14 women who believed that a family history of cancer was a major risk factor, half clearly articulated beliefs that they were not susceptible to cancer because of their negative family history. One woman said,

I don’t think I will ever get cancer until I die. I don’t have anyone in my family who has cancer, so I feel safe about that. I’ve never had lumps in my breasts. I heard cancer is hereditary. … Once again, I don’t think I have a chance of getting cervical cancer either, because none of my family members have ever had it.

Another woman stated, “I feel secure about [not getting breast cancer] because none of my family members have had breast cancer (laughter).”

With regard to diet, 11 women said that sweetened food and high-protein and high-fat diets could cause breast or cervical cancer. The majority of the women did not distinguish a specific diet as a factor for specific cancers but instead believed that fattening foods or chemicals in food, such as preservatives, can cause any type of cancer, including breast, cervix, colon, or stomach cancer. One woman said, “From what I’ve heard, fragments of rotten food accumulate in your veins and hinder your circulation, which can cause cancer. I do not know how this works because I am not an oncologist.”

Another woman specifically said that obesity is a risk factor for cancer because “being obese means having had too much fat in one’s diet.” Many women believed that eating healthful food would keep them from getting cancer. They also believed that eating Korean food would keep them safe because it has less fat.

Six women believed that stress could cause cancer. In particular, three women believed that paying too much attention to their health could cause any type of cancer, including breast and cervical cancer. Therefore, they believed that the stress and anxiety caused by cancer screening could be harmful to their health. They also believed that they would not get cancer as long as they were not too sensitive about health-related issues and did not worry about getting cancer.

The two etiologic factors for breast cancer mentioned most frequently were age and not breastfeeding. Women commonly talked about their higher risk of getting cancer as they got older. Women who related age to cancer were less likely to have had a mammogram in the prior year compared to those who did not talk about age. One woman said, “I always think that I have a chance of getting [breast] cancer because I am middle-aged.” Five women reported that breastfeeding was a protective factor against breast cancer; four of them reported feeling afraid of getting breast cancer because they had not breastfed their children, and the other woman expressed a lack of susceptibility to breast cancer because she had breastfed her children. Two women believed that having relatively small breasts could reduce or remove the risk of breast cancer, and one woman believed that an inverted nipple could cause breast cancer.

Regarding cervical cancer, some women associated the cervix with negative feelings. Five women believed that having a promiscuous lifestyle or having multiple sexual partners was related to getting cervical cancer. All of them linked promiscuity with being unclean. Among those five women, three were older than 65 years. Three participants believed that having many children could cause cervical cancer. Six women believed that hygiene was related to cancer; among those, four were older than 65 years. All six of the women believed that poor hygiene was related to cervical cancer, and one woman believed that poor hygiene was related to both breast and cervical cancer. She believed that because the breasts also are sexual organs, they have to be kept clean to prevent breast cancer, especially when a woman breastfeeds a baby.

Three older women also mentioned multiple abortions as a cause of cervical cancer. According to them, no readily available family-planning methods existed in Korea when they were young, which forced them to abort fetuses several times. Abortion at that time was a common practice among Korean women. One woman had given birth to nine babies and had aborted six or seven times; she believed that she had a higher chance of getting cervical cancer than other women who had had no abortions. Four women thought that problems related to menopause or menstruation, such as irregular periods or having a large quantity of blood or pain during menstruation, were related to having cervical cancer.

In terms of preventing or protecting from breast and cervical cancer, many participants believed that staying healthy, exercising regularly, having a positive attitude, not having stress, and not worrying about getting cancer would help prevent cancer. Two women who had not had a mammogram in the prior year stated that staying healthy would keep them from having breast cancer.

Many participants related their belief in God, fate, or destiny to breast and cervical cancer. One woman said that if it was God’s will, she would get cancer no matter what she did, and that if she were to get cancer, she would not receive any treatment because she wanted to accept reality. Another woman talked about not being stressed about receiving cancer screening because getting cancer depends on fate. One woman believed that having faith in God would lower her risk or prevent her from getting cancer because her faith helped to relieve her stress and she believed that stress was related to cancer. In relation to faith, five women believed that having faith was related to their mental health because it promoted inner peace, positive attitudes, and happiness and made them feel less lonely. Eight women believed that having faith was related to their physical health because they believed that having faith was related to their mental health, which ultimately was related to their physical health. One woman said getting cancer was just bad luck. Another woman said,

I don’t know. I never thought about [getting cancer]. I don’t think about why people get sick. If I happen to die, that’s fine. … I just think [getting cancer] is a matter of destiny. I don’t feel sad or unhappy about their situation. They just happen to have sickness; it’s their destiny.

Discussion

This study described symbolic meanings of their breasts and cervix as well as beliefs about breast cancer and cervical cancer from the perspective of Korean American women. Understanding how such nonfinancial factors may be barriers to screening is particularly relevant in an environment such as California, where financial barriers to screening and treatment among low-income women have been reduced. The researchers found different breast cancer screening behaviors among those who believed that diet, stress, age, and family history were related to breast cancer and those who did not mention such beliefs. However, no beliefs were related to the women’s cervical cancer screening behaviors. Findings from the study have many implications for researchers and clinicians. Four major considerations will be discussed.

Symbolic Meaning of Their Breasts and Cervix

First, the language used for Korean American women’s health-education messages related to breast cancer and cervical cancer must be selected carefully. Sensitivities to the use of the words “cancer,” “breasts,” and “cervix” should be acknowledged. The word that Korean American women choose to use in their daily lives to describe the breasts is more subjective, indirect, and modest (i.e., front chest) than the word that describes them as more objectified with a sexual or medical connotation. This may be, in part, a reason many of the participants in the study said they had never thought about the meanings of breasts or the cervix. It also may be the reason many of the subjects were fairly inarticulate about the topic. The findings are consistent with those reported in prior research. For example, Korean women were found to perceive the cervix as a private matter and not a topic for discussion, even among women (Im, Lee, & Park, 2002; Kim, Lee, Lee, & Kim, 2004), and most Korean women were not able to talk about the meaning of breasts (Im et al., 2004). The phenomenon exists for other groups, too. Many non-Korean Asian women and Muslim women also observe a proscription against talking about their breasts and are modest about exposing their breasts for screening purposes (Ashing, Padilla, Tejero, & Kagawa-Singer, 2003; Baron-Epel, Granot, Badarna, & Avrami, 2004; Bottorff et al., 1998). Similarly, the traditional Korean cultural taboo against exposing their bodies to others might deter Korean American women from accessing cancer screening services (Im, 2000).

When the participants in the study did talk about their breasts or the cervix, the symbolic meanings they attributed to their bodies were mostly related to being pregnant, having or rearing children, breastfeeding, or having abortions. The women’s symbolic meanings of their breasts and cervix were nearly all related to their interpersonal relationships with their family members, either children or husbands. Similar findings have been noted with Korean women in Korea, where perceptions of breasts were found to be connected to mothering roles (Im et al., 2004).

Beliefs Related to Screening Behaviors

Korean American women’s beliefs or limited knowledge about breast cancer and cervical cancer appear to mislead them into a false sense of being protected from cancer. The majority of the women did not perceive themselves to be at risk for breast or cervical cancer and believed that as long as they stay healthy, do not have a family history of cancer, eat a healthy diet, do not think or worry about it, and do not have multiple sexual partners or abortions, they would not be susceptible to breast or cervical cancer. Literature consistently reports that Korean American women’s lack of knowledge or confusion about breast and cervical cancer screening causes low utilization of screening services (Han, Williams, & Harrison, 2000; Juon et al., 2004; Lee, 2000; Yu, Hong, & Seetoo, 2003). For example, Korean American women’s most frequent reason for not having regular mammograms was their belief that they are at low risk for breast cancer (Juon et al., 2004). The women also believed that cervical cancer could be prevented by frequent douches, healthy diets, faith in God, or a positive mind set (Lee). Other Asian American women also have been found to believe that not thinking about cancer and having a positive attitude can protect them from cancer (Ashing et al., 2003; Bottorff et al., 1998). An especially interesting finding from the current study is that having knowledge about cancer, either correct or incorrect, may be a barrier to receiving screening tests. That is, a much higher percentage of women who had not received a mammogram in the prior year articulated risk factors for cancer than did women whose mammograms were up to date. The factors they cited included a family history of cancer, diet, stress, and aging.

Cancer and Faith in God

Korean American women appear to believe that their faith helps them in a positive way by relieving their stress, which, in turn, improves their mental and physical health and perhaps lowers cancer risk. Their belief in God appears to be interwoven with their belief in destiny, given that some women interpreted destiny as God’s will. In a previous study, Asian American community leaders identified the tendency of Asians to believe that having breast cancer is God’s will and that God has control of the outcome of illness (Ashing et al., 2003). Arab Israeli, Indian, and Jordanian women also tend to believe that everything comes from God, which causes them to believe that screening is not necessary (Baron-Epel et al., 2004; Choudhry, 1998; Petro-Nustas, 2001).

Age-Specific Beliefs About Cervical Cancer

Lastly, older Korean American women in particular related their abortion experiences and their husbands’ promiscuous lifestyles to cervical cancer. Women who lived during the era of traditional patriarchal Korean culture, when men were permitted to be promiscuous and women did not have options other than aborting their babies when they did not want to have any more children, appeared to have negative feelings about the cervix and cervical cancer. However, even though the older women tended to believe that they were at higher risk for cervical cancer from their life experiences, their cervical cancer screening rates were lower than those of their younger counterparts (Juon et al., 2003; Juon, Seo, & Kim, 2002). Older Korean American women’s cervical cancer screening behaviors may be more influenced by other factors, such as level of knowledge, feelings of embarrassment and shame, or beliefs in destiny, than by their beliefs about cervical cancer. Further research could clarify the reasons for low cancer screening rates in older Korean American women.

Implications for Nursing Practice and Research

The specific beliefs about breast cancer and cervical cancer described in the study may be useful in developing culture-specific intervention messages for Korean American women to increase their cancer screening behaviors. The reason they may be useful is that Korean American women’s symbolic meanings regarding their breasts and cervix as well as their beliefs related to those cancers may influence their screening behaviors.

Based on the findings of the study, educational messages related to breast cancer and cervical cancer must be selected carefully for culture-specific interventions. Educational messages for Korean American women should incorporate their beliefs, so that they can easily identify with and accept them. The educational messages should aim not only to increase their level of knowledge, but also to reframe, refocus, and rebuild their existing knowledge or health beliefs in a creative way. This could be more effective than simply providing a medical model of knowledge in attempting to change Korean American women’s cancer screening behaviors. More attention should be paid to choosing the appropriate language to describe the breasts, cervix, and breast and cervical cancer in intervention messages. To choose culturally sensitive language for intervention messages, careful selection of translators and the translation process is recommended to maintain sensitivity to researchers’ intentions in delivering the messages and participants’ perceptions in interpreting the messages.

Reframing Korean American women’s knowledge and attitudes about breast cancer and cervical cancer also may be very important. Those performing interventions can emphasize that not having a family history of cancer, eating a healthy diet, and having positive attitudes can be very helpful in maintaining health but that more is needed to detect breast cancer and cervical cancer early, when they can be treated most easily and effectively. Women’s faith in God or belief in destiny might be reframed by stating that God wants women to take care of themselves, that God provides healthcare professionals and screening technologies to enable them to do so, or that their destiny is to find cancer early and then be cured. For older women’s negative life experiences, such as having had multiple abortions or unhappy relationships with their husbands, special intervention messages aimed at improving their negative perceptions about the cervix and cervical cancer may be helpful in increasing their cervical cancer screening rates.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by an institutional postdoctoral fellowship in the College of Nursing at the University of Iowa (T32 NR07058), a National Institute of Nursing Research Mentored Research Scientist Development Award (K01 NR 08096), and an award to Lee from the faculty research fund at the University of San Diego in California.

Footnotes

This material is protected by U.S. copyright law. Unauthorized reproduction is prohibited. To purchase quantity reprints, please e-mail reprints@ons.org or to request permission to reproduce multiple copies, please e-mail pubpermissions@ons.org.

References

- Ashing KT, Padilla G, Tejero J, Kagawa-Singer M. Understanding the breast cancer experience of Asian American women. Psycho-Oncology. 2003;12(1):38–58. doi: 10.1002/pon.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Epel O, Granot M, Badarna S, Avrami S. Perceptions of breast cancer among Arab Israeli women. Women and Health. 2004;40:101–116. doi: 10.1300/J013v40n02_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottorff JL, Johnson JL, Bhagat R, Grewal S, Balneaves LG, Clarke H, et al. Beliefs related to breast health practices: The perceptions of South Asian women living in Canada. Social Science and Medicine. 1998;47:2075–2085. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00346-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhry UK. International scholarship. Health promotion among immigrant women from India living in Canada. Image—Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1998;30:269–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1998.tb01304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin SS, Uhler RJ, Hall HI, Briss PA. Nonadherence to breast and cervical cancer screening: What are the linkages to chronic disease risk? Preventing Chronic Disease. 2004;1(1):A04. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Deapen D, Liu L, Perkins C, Bernstein L, Ross RK. Rapidly rising breast cancer incidence rates among Asian American women. International Journal of Cancer. 2002;99:747–750. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good BJ. Medicine, rationality, and experience: An anthropological perspective. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Han Y, Williams RD, Harrison RA. Breast cancer screening knowledge, attitudes, and practices among Korean American women. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2000;27:1585–1591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Im E, Meleis AI. Meanings of menopause to Korean immigrant women. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2000;22:84–102. [Google Scholar]

- Im EO. A feminist critique of breast cancer research among Korean women. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2000;22:551–570. doi: 10.1177/01939450022044593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Im EO, Lee EO, Park YS. Korean women’s breast cancer experience. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2002;24:751–765. doi: 10.1177/019394502762476960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Im EO, Park YS, Lee EO, Yun SN. Korean women’s attitudes toward breast cancer screening tests. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2004;41:583–589. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juon H, Seo YJ, Kim MT. Breast and cervical cancer screening among Korean American elderly women. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2002;6:228–235. doi: 10.1054/ejon.2002.0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juon HS, Choi Y, Kim MT. Cancer screening behaviors among Korean American women. Cancer Detection and Prevention. 2000;24:589–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juon HS, Kim M, Shankar S, Han W. Predictors of adherence to screening mammography among Korean American women. Preventive Medicine. 2004;39:474–481. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juon HS, Seung-Lee C, Klassen AC. Predictors of regular Pap smears among Korean American women. Preventive Medicine. 2003;37:585–592. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Lee KJ, Lee SO, Kim S. Cervical cancer screening in Korean American women: Findings from focus group interviews. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing. 2004;34:617–624. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2004.34.4.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Yu ES, Chen EH, Kim J, Kaufman M, Purkiss J. Cervical cancer screening knowledge and practices among Korean-American women. Cancer Nursing. 1999;22:297–302. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199908000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A. Patients and healers in the context of culture. Vol. 3. Cambridge, MA: Schenkman; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A, Seeman D. Personal experience of illness. In: Scrimshaw S, editor. Handbook of social studies in health and medicine. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2000. pp. 230–242. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzel AJ. Sampling in qualitative inquiry. In: Miller WL, editor. Doing qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1992. pp. 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lee EE, Fogg L, Sadler GR. Factors of breast cancer screening among Korean immigrants in the United States. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2006;8:223–233. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-9326-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MC. Knowledge, barriers, and motivators related to cervical cancer screening among Korean American women: A focus group approach. Cancer Nursing. 2000;23:168–175. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200006000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupton D. The social construction of medicine and the body. In: Scrimshaw S, editor. Handbook of social studies in health and medicine. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2000. pp. 50–63. [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Miller BA, Kolonel LN, Bernstein L, Young JL, Swanson GM, West DW, et al., editors. Racial/ethnic patterns of cancer in the United States 1988–1992. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Moskavitz JM, Kazinets G, Tager IB, Wong J. Breast and cervical cancer screening among Korean women—Santa Clara County, California, 1994 and 2002. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2004;53:765–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative interviewing. In: Patton MQ, editor. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1990. pp. 277–359. [Google Scholar]

- Petro-Nustas WI. Factors associated with mammography utilization among Jordanian women. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2001;12:284–291. doi: 10.1177/104365960101200403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers B, Cowles K. The qualitative research audit trail: A complex collection of documentation. Research in Nursing and Health. 1993;16:219–226. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770160309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler GR, Nguyen F, Doan Q, Au H, Thomas AG. Strategies for reaching Asian Americans with health information. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998;14:224–228. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(97)00067-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler GR, Ryujin LT, Ko CM, Nguyen E. Korean women: Breast cancer knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. BMC Public Health. 2001;1(1):7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing and Health. 2000;23:334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Finding the findings in qualitative studies. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2002;34:213–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2002.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarna L, Tae YS, Kim YH, Brecht ML, Maxwell AE. Cancer screening among Korean Americans. Cancer Practice. 2001;9:134–140. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2001.009003134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ursin G, Wu AH, Hoover RN, West DW, Nomura AM, Kolonel LN, et al. Breast cancer and oral contraceptive use in Asian American women. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1999;150:561–567. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wismer BA, Moskowitz JM, Chen AM, Kang SH, Novotny TE, Min K, et al. Mammography and clinical breast examination among Korean American women in two California counties. Preventive Medicine. 1998a;27:144–151. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1997.0259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wismer BA, Moskowitz JM, Chen AM, Kang SH, Novotny TE, Min K, et al. Rates and independent correlates of Pap smear testing among Korean American women. American Journal of Public Health. 1998b;88:656–660. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.4.656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu MY, Hong OS, Seetoo AD. Uncovering factors contributing to underutilization of breast cancer screening by Chinese and Korean women living in the United States. Ethnicity and Disease. 2003;13:213–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]