Abstract

Seasonal anestrus in ewes is driven by an increase in response to estradiol (E2) negative feedback. Compelling evidence indicates that inhibitory A15 dopaminergic (DA) neurons mediate the increased inhibitory actions of E2 in anestrus, but these neurons do not contain estrogen receptors. Therefore, we have proposed that estrogen-responsive afferents to A15 neurons are part of the neural circuit mediating E2 negative feedback in anestrus. This study examined the possible role of afferents containing γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and nitric oxide (NO) in modulating the activity of A15 neurons. Local administration of NO synthase inhibitors to the A15 had no effect on LH, but GABA receptor ligands produced dramatic changes. Administration of either a GABAA or GABAB receptor agonist to the A15 increased LH secretion in ovary-intact ewes, suggesting that GABA inhibits A15 neural activity. In ovariectomized anestrous ewes, the same doses of GABA receptor agonist had no effect, but combined administration of a GABAA and GABAB receptor antagonist to the A15 inhibited LH secretion. These data are consistent with the hypothesis that endogenous GABA release within the A15 is low in ovary-intact anestrous ewes and elevated after ovariectomy. Using dual immunocytochemistry, we observed that GABAergic varicosities make close contacts on to A15 neurons and that A15 neurons contain both the GABAA-α1 and the GABAB-R1 receptor subunits. Based on these data, we propose that in anestrous ewes, E2 inhibits release of GABA from afferents to A15 DA neurons, increasing the activity of these DA neurons and thus suppressing episodic secretion of GnRH and LH.

REPRODUCTION IS UNIQUE among physiological systems in that it can be shut down for prolonged periods. In females, the most common instances of such suppression are the anovulation that occurs before puberty (1), during lactation (2), and annually in seasonally breeding species (3,4). Over the last two decades, considerable progress has been made in understanding the neuroendocrine mechanisms underlying seasonal breeding in sheep. It is now well established that a dramatic annual shift in the response to the negative feedback actions of estradiol (E2) causes seasonal breeding in ewes (4,5). The nonbreeding (anestrous) season occurs because E2 gains the capacity to potently inhibit GnRH and LH pulse frequency at this time of year (4,5) so that the low amounts of E2 secreted by the ovary are responsible for the slow LH pulse frequency observed in ovary-intact anestrous ewes (6).

A group of dopaminergic (DA) neurons located at the base of the brain in the retrochiasmatic (RCh) area of the ovine hypothalamus plays a key role in mediating these seasonal changes in response to E2 negative feedback (5,7). These DA neurons inhibit LH pulse frequency (8,9) in anestrus, but not the breeding season, and their activity is stimulated by E2 only during anestrus (10,11,12). Because A15 DA neurons do not contain either estrogen receptor-α (ERα) or ERβ (13,14,15), they are most likely stimulated by afferent input from estrogen-responsive interneurons. Afferent neurons containing ERα have been identified in the ventromedial preoptic area (vmPOA) and RCh (16), and local administration of E2 to these areas acts via a DA system to inhibit LH pulse frequency in anestrous, but not breeding-season, ewes (17,18,19).

Although two anatomical locations of estrogen-responsive afferents to A15 neurons have been identified, the phenotype of these neurons remains unknown. Likely candidate neurotransmitters, based on dual-label immunocytochemical studies (5,20,21,22,23), include γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) (20), glutamate (21), nitric oxide (22), and dynorphin (23). The latter can be excluded because endogenous opioids are not involved in E2 negative feedback in anestrus (24,25). In the present studies, we examined the possible roles of nitric oxide (NO) and GABA and obtained strong anatomical and pharmacological evidence that GABAergic neurons mediate, at least in part, the effects of E2 on these DA neurons. In light of these data, we also determined whether there were seasonal changes in GABA input or GABA receptors that could account for seasonal differences in the ability of E2 to stimulate A15 neurons.

Materials and Methods

Animal handling and surgical procedures

Mature, black-faced ewes with a history of normal reproductive cycles were moved indoors 3–7 d before the procedures and housed two per pen under artificial lighting with duration similar to that outdoors. They were fed a maintenance level of alfalfa pellets supplemented with grain and minerals and had free access to water. All pharmacological experiments were done during the anestrous season (from May through early August), and infertility was confirmed by undetectable progesterone concentrations and/or absence of corpora lutea at ovariectomy (OVX). For seasonal comparisons, we used tissue collected during anestrus and the breeding season (October through December) from E2-treated OVX ewes (11,16) to avoid confounding effects of different circulating ovarian steroids in the two seasons.

All surgeries were done using sterile techniques with animals anesthetized with oxygen plus nitrous oxide, supplemented with 1–4% halothane as needed. Ovaries were removed via midventral laparotomy. For anatomical studies (experiments 6–8), OVX ewes were given a 3-cm-long sc SILASTIC brand (Dow Corning Corp., Midland, MI) implant containing E2 (9,11) at the time ovaries were removed. Bilateral stainless steel guide tubes (18 gauge) aimed at the A15 area were stereotaxically implanted as previously described (17,19). Briefly, a 2-cm-diameter hole was drilled in the skull, the sagittal sinus ligated, and radioopaque dye injected into one lateral ventricle. Positive ventrilography in both sagittal and coronal planes was used to place the tips of the guide tubes at the posterior edge of the optic chiasm, 2.0 mm dorsal to the base of the brain and 3.0 mm lateral to midline. After protecting the surface of the brain with gel foam and a nylon mesh, guide tubes were cemented in place with cranial screws and dental acrylic, plugged with 22-gauge wire stylets, and protected with a plastic cap. All animals were treated pre- and postoperatively with dexamethasone and antibiotics, received analgesic just before surgery, and were allowed to recover for at least 2 wk before being used in an experiment. All procedures involving animals were approved by the West Virginia University Animal Care and Use Committee.

Reagents

The GABAA receptor agonist muscimol and antagonist (−)-bicuculline methochloride were purchased from Tocris (Ellisville MO). A GABAB receptor agonist [R-(+)-baclofen] and antagonist (phaclofen) were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis MO), and a second GABAB antagonist (CGP52432) came from Tocris. These drugs have been extensively used to examine the role of different GABA receptors in control of GnRH secretion in rodents and sheep (26,27). Nitric oxide synthesis (NOS) inhibitors S-methyl thiocitrulline (SMTC) and NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME) (28) were purchased from Sigma. All drugs were stored in crystalline form according to the directions of the manufacturer. When used for microinjections, drugs were dissolved in sterile water and used within 2 wk. Primary antisera used for immunocytochemical (ICC) studies were mouse anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (anti-TH), rabbit antibodies against glutamic acid decarboxylase 67 (GAD67) and GABAA receptor α (GABAA-Rα1) (all from Chemicon International, Temecula, CA), and guinea pig antisera against GABAB receptor-1 (GABAB-R1) (Research Diagnostics, Concord, MA). Antisera against GAD67 and GABA receptor subunits were chosen after screening a number of commercially available antibodies for use in sheep (data not shown).

General experimental protocols

Blood samples were collected by jugular venipuncture every 12 min from 36 min before to 4 h after insertion of microimplants or microinjections (ovary-intact animals) or for 2–3 h before and 3 h after microinjections (OVX ewes). Blood was allowed to clot overnight, and serum was harvested and stored at −20 C until assayed. For microimplants (experiment 1), drugs were tamped into the lumen of 22-gauge stainless steel tubing cut to extend 1–2 mm beyond the end of the guide tube. Microimplants were inserted and left in place for the 4 h of frequent blood collection and then replaced with stylets. For microinjections, drugs were dissolved in sterile water and 300 nl (or 400 nl for experiment 5b) rapidly injected bilaterally using a 1-μl Hamilton syringe with fixed needle that extended 1–2 mm beyond the end of the guide tubes. These volumes were selected, based on the spread of tract tracers (16), to encompass the A15 without encroaching on the third ventricle (estimated injection radius of 1.5–2 mm). The doses of drugs (range of 1.5–3 μg/injection) were based on previous work in sheep, which delivered doses of GABA receptor ligands of 10 μg (29,30), 4.5–8 μg (31), or 15–45 μg (32). Ewes were treated with gentamicin (250 mg im) prophylactically after each blood collection period. Experiments used a replicate design so that all animals received each experimental and control treatment, in random order, with 4–5 d between treatments.

Tissue collection

At the end of the experiment, fixed tissue was collected from drug-treated ewes for histological verification of microinjection/implant sites and for ICC analysis. Ewes were injected before perfusion twice (10 min apart) with 25,000 U heparin iv, followed by sodium pentobarbital (about 4–5 g iv). When the animal had stopped breathing, we quickly removed its head and perfused the brain via both internal carotid arteries with 6 liters of 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 m phosphate buffer (PB) containing 10 U heparin/ml and 0.1% sodium nitrite (pH 7.4). A block of tissue containing preoptic and hypothalamic tissue was dissected out, incubated in the same fixative overnight (4 C), and then infiltrated with 20% sucrose in PB. Thick coronal sections (50 μm) were cut using a freezing microtome and either stored at −20 C in cryopreservative until processed for dual ICC, or every fifth section was mounted on slides and stained with cresyl violet for identification of treatment sites.

Hormonal and immunocytochemical procedures

LH concentrations were measured in duplicate 100- or 200-μl aliquots of serum by RIA as previously described (23); assay sensitivity averaged 0.6 ng/ml (NIH S24), and inter- and intraassay coefficients of variation of a pool that produced 60% displacement of iodinated LH were 11 and 21%, respectively. Progesterone was measured in selected samples to confirm ewes were in anestrus using a commercially available kit (Diagnostic Systems Laboratories, Inc., Webster, TX) validated for use in sheep (23), with a sensitivity of 0.05 ng/ml.

We used dual-ICC and confocal microscopy to determine whether GABAergic terminals make close contacts onto A15 neurons and whether A15 neurons contained GABAA and/or GABAB receptors. Tyramide amplification (33) was used to amplify the primary antibodies against GAD67, GABAA-Rα1, GABAB-R1, as previously described (34). Briefly, two to three free-floating sections per area per ewe from the RCh were washed in 0.1 m PB and then incubated sequentially in 1% H2O2 for 10 min at room temperature (RT), 4% blocking sera (normal goat or donkey serum; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove PA) for 1 h in PBS or PBS containing 0.4% Triton X-100 (TxBS), and primary antisera for 24–48 h (Table 1). Sections were then washed in PB and incubated sequentially at RT in 1) 1:200 biotinylated second antibody (Jackson) for 1 h, 2) 1:200 Vectastain ABC-elite (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 1 h, 3) 1:250 TSA Biotin System (tyramide signal amplification; PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Norwalk, CT) in PBS containing 0.003% H202 for 10 min, and 4) streptavidin conjugated to Cy3 (Jackson) or Alexa 555 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 30–60 min (Table 1). To visualize A15 DA neurons, sections were next incubated in 4% blocking sera (normal donkey serum for GAD-stained sections; normal goat serum for others) for 1 h, followed by 1:5000 mouse anti-TH for 24 h at RT and then 1:200 donkey or goat antimouse conjugated to Alexa 488 (Jackson). Sections were washed in PB, mounted on slides, and coverslipped with gelvatol to prevent fading. Primary antisera used have been already characterized (34,35,36,37). Omission of one primary antigen had no effect on fluorescent signal from the other antigen but eliminated fluorescent signal of the antigen targeted by the primary antibody.

Table 1.

Primary reagents used for immunocytochemistry for GABA-related antigens

| Reagent | GAD67 | GABAA-Rα1 | GABAB-R1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blocking sera | 4% NGS in PBS | 4% NDS in PBS | 4% NDS in 0.4% TxBS |

| Primary antisera | Rabbit anti-GAD 1:5000; 48 h at 4 C | Mouse anti-GABAA 1:55,000; 24 h at RT | Guinea-pig anti GABAB 1:100; 24 h at RT |

| Biotinylated secondary antisera | Goat antirabbit | Donkey antimouse | Donkey anti-guinea pig |

| Tyramide amplification | Vector ABC-Elite, TSA Biotin System | Vector ABC-Elite, TSA Biotin System | Vector ABC-Elite, TSA Biotin System |

| Fluor | CY3-strepavidin 1:100; 30 min at RT | CY3-strepavidin 1:400; 1 h at RT | Alexa 555-strepavidin 1:100; 1 h at RT |

Reagents were from Chemicon (anti-GAD and anti-GABAA-Rα 1), Research Diagnostics (GABAB-R1), Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (second antibodies, Cy3-steptavidin), Vector Laboratories (Vector ABC-Elite), PerkinElmer Life Sciences (TSA Biotin System), Molecular Probes (Alexa 555-stepavidin). NDS, Normal donkey serum; NGS, normal goat serum; TxBS, Triton X-100 in buffered saline.

Data analysis

LH pulses were identified using the following well established (38) criteria: 1) the peak of the pulse occurred within two samples of the previous nadir, 2) the amplitude of the peak was greater than the sensitivity of the assay, and 3) the LH concentration at the peak exceeded the 95% confidence limits (based on the variability of the standard curve) of the concentrations at both the preceding and subsequent nadirs. For OVX animals, LH pulse frequency, interpulse interval, and mean LH concentration were calculated for pre- and posttreatment periods. A within-subjects design was used to analyze effects of drug treatments. Specifically, mean LH and interpulse interval were analyzed using two-way ANOVA with repeated measures (interpulse interval was used to assess episodic secretion because it can be analyzed by parametric statistics, whereas pulse frequency cannot) using SigmaStat 3.11 software. The infrequent pulses in control ovary-intact anestrous ewes precluded use of interpulse interval. Therefore, LH pulse frequency and mean LH concentration were determined for each ewe during the 4-h posttreatment period of ovary-intact ewes. Significant effects of receptor ligands (compared with controls) on LH pulse frequency in ovary-intact ewes were determined by the Friedman two-way ANOVA by ranks, a nonparametric within-subject analysis, and the effects on mean LH concentrations were determined by ANOVA, with repeated measures.

Images of at least 12 TH-immunoreactive neurons per section per ewe and either GAD67 (A15 only), GABAA-Rα1 (A15, A14, and A12 regions), or GABAB-R1 (A15, A14, and A12 regions) were acquired using a Carl Zeiss Axiovert 100M Laser Scanning Microscope (Carl Zeiss International, Thornwood, NY) operated by LSM 510 software (confocal microscopy; Carl Zeiss). Scans at each appropriate wavelength were done independently to avoid bleed-through between channels. Two sets of images were taken along the z-plane (z-stack) for each neuron, consisting of 18–22 images in each channel that sliced the neuron from top to bottom at intervals of 1–1.5 μm determined by the confocal software based on the size of the neuron. These z-stacks were then converted to a series of tif files. For GAD67-containing varicosities, close contacts were identified on individual z-sections, and the percentage of DA neurons with at least one close contact and the number of close contacts per neuron were calculated. Receptor data are expressed as percentage of DA neurons that coexpressed the receptor subunit. For percentages, data were transformed (arcsine of square root) and then compared between season and hypothalamic area by two-way ANOVA.

Results

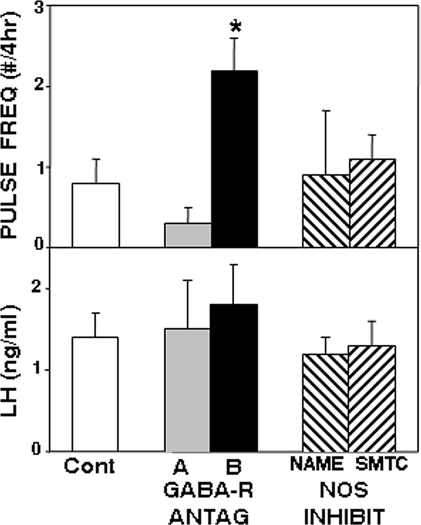

Experiment 1: effects of A15 microimplants of GABA receptor antagonists and NOS inhibitors

As a first test of the role of GABA and NO in the control of A15 neural activity, we examined the effects of microimplants of GABA receptor antagonists and NOS inhibitors, containing about 250 μg drug, in the A15 on episodic LH secretion in ovary-intact anestrous ewes. Seven of 11 ewes had correct placements of microimplants in the A15. For this and subsequent experiments, data from misplaced treatments were excluded from the analysis. As expected, when ewes received control (empty) microimplants LH pulse frequency was less than one pulse/4 h (Fig. 1), which is typical of ovary-intact anestrous ewes. Phaclofen (GABAB receptor antagonist) microimplants appeared to induce LH pulses in five animals and significantly (P < 0.05) increased LH pulse frequency, an effect that might be due to stimulation of endogenous GABA release via GABAB autoreceptors (27,39). However, this stimulatory action of phaclofen was modest because it did not alter mean LH concentration (Fig. 1). Microimplants containing bicuculline (GABAA receptor antagonist) or the nonspecific (l-NAME) or neuron-specific (SMTC) NOS inhibitors had no affect on LH pulse frequency or LH concentrations in these ewes. Microimplants containing NOS inhibitors were empty when removed from the ewes, whereas crystalline GABA receptor antagonists were still visible in the lumen at the end of treatments. Most of the animals treated with bicuculline had increased motor activity while the microimplants were in place; no behavioral effects were observed with phaclofen or the NOS inhibitors. Misplaced sites were rostral, caudal, or through the base of the brain; treatments in these areas produced no alterations in LH secretion (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Effects of A15 microimplants containing antagonists (ANTAG) to GABAA (shaded bars) receptors (bicuculline), GABAB (solid bars) receptors (phaclofen), and the NOS inhibitors (INHIBIT) (striped bars), l-NAME and SMTC, on LH pulse frequency (top panel) and mean LH concentrations (bottom panel) in ovary-intact anestrous ewes. *, P < 0.05 vs. control (Cont) treatment; there were no significant differences in mean LH (F = 1.2; P > 0.1).

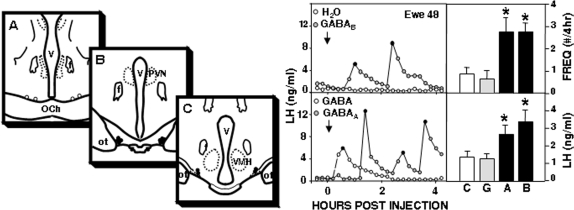

Experiment 2: effect of A15 microinjections of GABA receptor agonists in ovary-intact ewes

Because the GABAB receptor can sometimes function as an autoreceptor (27,39), the effects of phaclofen in experiment 1 could have been due to pharmacological stimulation of endogenous GABA release. Therefore, we next tested the effects of local administration of GABA receptor agonists into the A15 region on LH secretion using another group of ovary-intact anestrous ewes. Preliminary work indicated that microimplants of GABA agonists produced partial sedation. Therefore, drugs were administered as bilateral microinjections of 300 nl containing 10 μg drug/μl sterile water (n = 9), because this concentration of GABA receptor agonists altered LH secretion when injected into the POA of anestrous ewes (30). Specifically, water (control), GABA (3 μg; 28.6 nmol), the GABAA receptor agonist musimol (3 μg; 24.7 nmol), or the GABAB receptor agonist baclofen (3 μg; 12.0 nmol) were injected into all ewes in random order, with 4 d between treatments. No sedation or other behavioral effects were observed with any microinjection.

All seven ewes with microinjections in the A15 area (Fig. 2) responded to either the GABAA or GABAB receptor agonist with an increase in episodic LH secretion above that seen with control treatments (Fig. 2). Both agonists significantly increased both LH pulse frequency (P < 0.05) and mean LH concentrations (F = 5.85; P < 0.01). The first LH pulse occurred with a considerable delay after microinjection of either the GABAA (68.6 ± 12.2 min) or the GABAB (46.2 ± 7.6 min) receptor agonist. However, once episodic LH secretion had started, these agonists produced LH pulse frequencies (GABAA: 2.7 ± 0.2 pulses/3 h; GABAB: 2.3 ± 0.3 pulses/3 h) similar to those seen in OVX ewes (see Table 2). Microinjection of GABA increased episodic LH release in only three of seven ewes and did not significantly increase LH concentrations or pulse frequency (Fig. 2). Misplaced microinjections (n = 2, both rostral to the A15, open circles in Fig. 2) had no effect on LH release (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Left, Location of microinjection sites in experiments 2 and 3 shown on schematics of coronal sections though the ovine RCh area. Pairs of circles depict bilateral location in a single ewe. Missed microinjections, represented by open circles, were rostral to the A15 (A). Filled circles depict microinjections in either the central region (B, n = 5) or caudal region (C, n = 2) of the A15 cell group. Right, Effect of A15 microinjections (arrows) of water, GABA, the GABAA agonist muscimol, and the GABAB agonist baclofen on episodic LH secretion in a representative ovary-intact anestrous ewe. Solid circles depict peaks of LH pulses. Bars on the right depict mean (±sem, n = 7) LH pulse frequency (FREQ, top panel) and LH concentration (bottom panel) after treatment of ovary-intact ewes with A15 microinjections of water (C), GABA (G), muscimol (A), or baclofen (B). *, P < 0.05 vs. control (water) treatments. f, Fornix; OCh, optic chiasm; ot, optic tracts; PVN, paraventricular nucleus; V, third ventricle; VMH, ventromedial hypothalamus.

Table 2.

Effect of microinjections of GABA receptor agonists and antagonists into the A15 area on LH secretion in OVX anestrous ewes

| Treatment | Pulse frequency (no./3 h)

|

Mean LH (ng/ml)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

| Experiment 3 | ||||

| Control | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 8.7 ± 1.0 | 9.0 ± 1.1 |

| Muscimol | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 3.1 ± 0.3 | 11.5 ± 1.9 | 10.2 ± 1.3 |

| Baclofen | 3.1 ± 0.3 | 3.3 ± 0.3 | 11.1 ± 2.6 | 11.5 ± 1.9 |

| Bicuculline | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 9.6 ± 1.6 | 7.2 ± 1.3 |

| Phaclofen | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 8.6 ± 2.0 | 9.1 ± 1.8 |

| Experiment 4 | ||||

| Control | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 2.4 ± 0.4 | 9.5 ± 1.5 | 12.8 ± 1.6 |

| CGP52432 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 9.2 ± 2.2 | 10.4 ± 1.7 |

Results are shown as mean ± sem. Pre, Before microinjection; Post, after microinjection.

Experiment 3: effects of A15 microinjections of GABA agonists and antagonists in OVX ewes

The ability of GABA agonists to stimulate LH secretion observed in experiment 2 raised the possibility that endogenous release of GABA inhibits A15 DA neurons. If this is the case, then E2 should inhibit these GABAergic afferents because this steroid stimulates A15 neurons. Consequently, GABA release would be expected to be low in ovary-intact ewes and elevated in OVX animals. Thus, administration of GABA agonists that increased LH secretion when injected into the A15 of ovary-intact ewes should have little, or no, effect in OVX animals, whereas GABA antagonists should inhibit LH secretion. To test these predictions, we OVX the animals used in experiment 2. Starting 2 wk later, blood samples were collected for 3 h before and 3 h after bilateral microinjection of 300 nl sterile water containing muscimol (3 μg; 24.7 nmol), baclofen (3 μg; 12.0 nmol), bicuculline (1.5 μg; 3.4 nmol), or phaclofen (2.7 μg; 10.8 nmol) into the A15 (doses of antagonists were decreased due to low solubility in water) using a Latin-square design with 4–5 d between treatments.

LH pulse patterns with control treatments (and before drugs) showed the relatively slow frequency (about one pulse every 70–90 min) pattern typical of OVX ewes in the anestrous season (Table 2). In the seven ewes with properly placed injections, neither agonist nor antagonist significantly altered interpulse interval (F = 1.64; P > 0.1 for interaction of time × treatment) or mean LH concentrations (F = 0.28; P > 0.8 for interaction of time × treatment). Two animals given bicuculline were briefly hyperactive, but there were no obvious behavioral effects of the other drugs.

Experiment 4: effects of A15 microinjections of a more potent GABAB receptor antagonist in OVX ewes

The lack of effects of GABA receptor agonists in OVX ewes (experiment 3) are consistent with the hypothesis that endogenous GABA release is high in these animals, but the lack of effects of the GABA antagonists is not. One possible explanation for this discrepancy is that an insufficient dose of GABA receptor antagonist was given. This seems unlikely with the GABAA antagonist because it produced some behavioral effects but could account for the lack of effects of phaclofen, which is a fairly weak agonist (40). Therefore, we tested the effects of a more potent GABAB antagonist, CGP52432 (40,41) using another group of ewes.

We first tested the effects of local administration of baclofen in ovary-intact animals (n = 5 with correct microinjections) to confirm earlier data. Microinjections of this GABAB receptor agonist (3 μg; 12.0 nmol) again significantly increased LH pulse frequency (2.8 ± 0.2 pulse/4 h) above that observed with vehicle control (1.2 ± 0.4 pulse/4 h). Animals were then OVX and, starting 17 d later, the effects of CGP52432 (1.5 μg; 7.8 nmol) were compared with vehicle (sterile water) using a crossover design. Blood samples were collected for 2 h before and 3 h after injection of water or CGP52432. Similar to phaclofen, this GABAB receptor antagonist had no effect (Table 2) on LH pulse frequency (F = 0.15; P > 0.6 for interaction of time × treatment), or mean LH concentrations (F = 1.6; P > 0.2 for interaction of time × treatment).

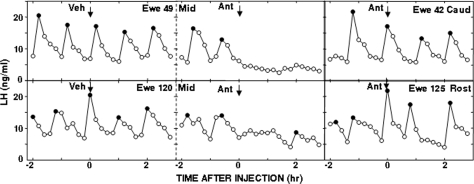

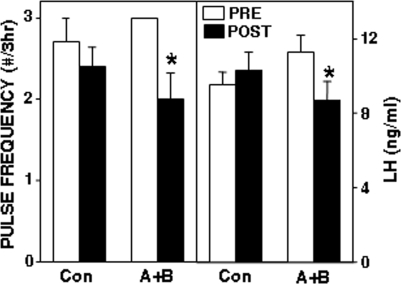

Experiment 5: effects of combined blockade of GABAA and GABAB receptors in the A15 region in OVX ewes

Because A15 neurons responded to both the GABAA and the GABAB receptor agonist (experiment 2) and appear to contain both receptors (see experiments 7 and 8), it may be necessary to block both GABAA and GABAB receptors simultaneously to relieve GABAergic inhibition and activate sufficient DA release to inhibit GnRH and LH secretion in OVX ewes. Therefore, we tested the effects of microinjection of a combined dose of bicuculline (2.5 μg/μl) and CGP52432 (2.5 μg/μl) into the A15 of OVX ewes in two replicates. In the first replicate, performed in summer of 2005, blood samples were collected every 12 min for 2 h before and 3 h after bilateral injection of 300 nl water or antagonists (1.7 nmol bicuculline plus 1.9 nmol CGP52432) into five OVX ewes, using a crossover design. The second replicate, done in eight OVX ewes during the summer of 2006, was similar in design except that, based on the results of the first experiment, the injection volume was increased to 400 nl (2.3 nmol bicuculline plus 2.7 nmol CGP52432).

In the first replicate, the antagonists tended to decrease LH concentrations (from 8.7 ± 0.7 to 5.7 ± 1.4 ng/ml; F = 3.5; P = 0.083 for interaction of time × treatment) and LH pulse frequency (from 2.6 ± 0.4 to 1.3 ± 0.7 pulses/3 h; F = 3.42; P = 0.088 for interaction of time × treatment by ANOVA of interpulse interval) in the four ewes with microinjections in the A15, whereas microinjections of vehicle produced no obvious changes in LH pulse patterns (Fig. 3). However, LH pulses were completely abolished in the two ewes with injections in the center of the A15 (Fig. 3) but were not obviously affected in the other two ewes, with injections in either the rostral or caudal portion of the A15. In the second replicate, the combined antagonists significantly reduced mean LH concentrations and decreased LH pulse frequency in the five ewes with correct placements in the A15 (Fig. 4). No effects of antagonists were observed in ewes with injections that missed the A15 (one ewe in the first replicate, two in the second). If data from the two replicates were combined, there was a significant effect of placement of the microinjection within the A15 (Fig. 5), with injections in the center of the A15 inhibiting LH pulse frequency (F = 17.1; P = 0.001 for time × treatment interaction) and LH concentrations (F = 5.55; P = 0.036 for time × treatment interaction), whereas those on the periphery did not (F = 0.97; P > 0.3 for time × treatment interaction on interpulse interval).

Figure 3.

Left, LH pulse patterns before and after microinjection (arrows) of water (left panels) or the combination of bicuculline and CGP52432 (middle panels) into the central portion of the A15 of representative OVX anestrous ewes. Right panels, LH pulse patterns in representative ewes receiving the combination of antagonists into either the caudal (Caud) or rostral (Rost) portion of the A15. Top panels present data from the first replicate, whereas data from the second replicate of experiment 5 are shown in the bottom panels. Solid circles are peaks of LH pulses. Ant, Combined antagonists; Mid, injection in middle portion of A15; Veh, vehicle.

Figure 4.

A combination of GABAA and GABAB antagonists inhibits LH pulse frequency in OVX anestrous ewes. Bars depict mean (±sem, n = 5) LH pulse frequency (left panel) and LH concentration (right panel) before (open bars) and after (solid bars) microinjection of water (Con) or bicuculline plus CGP52432 (A+B) into the A15 of OVX anestrous ewes. *, P < 0.05 vs. pretreatment values.

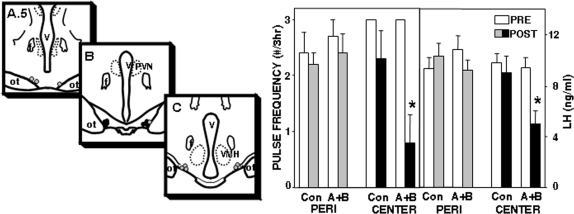

Figure 5.

Left, Distribution of microinjection sites within the A15 shown on schematic coronal sections through the A15 region (experiment 5). Microinjections in the rostral (A.5) and caudal (C) portions of the A15 are depicted by shaded circles, whereas microinjections in the central portion of the A15 (B) are shown by solid circles. Note that the rostral panel is posterior to A in Fig. 2. Location of missed sites is not illustrated. Right, Only microinjections in center of A15 inhibit LH pulses. Bars depict mean (±sem) pulse frequency and LH concentration before (open bars) and after (shaded and solid bars) microinjection of water (Con) or bicuculline plus CGP52432 (A+B) into either the peripheral (PERI) or central region of the A15 of OVX anestrous ewes. *, P < 0.05 vs. pretreatment values.

Experiment 6: GAD67-immunoreactive close contacts on A15 neurons

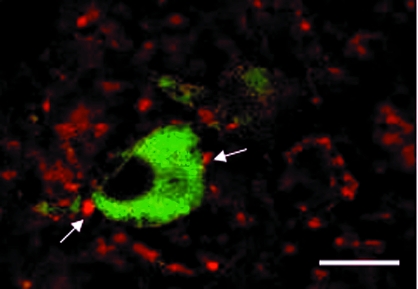

Every DA (i.e. TH-immunopositive) neuron examined had at least one GAD-positive close contact (Fig. 6), with more close contacts on dendritic processes (9.0 ± 2.0, n = 6 ewes) than on cell soma (5.1 ± 0.2). Not surprisingly, there was also a relatively widespread distribution of GAD67-containing varicosities that were not associated with TH immunoreactivity (Fig. 6). The number of GAD67-containing close contacts on A15 DA neurons in OVX, E2-treated breeding-season ewes (dendrites: 7.8 ± 0.8; cell soma: 4.6 ± 0.6 close contacts, n = 5 ewes) was not significantly different from those observed during anestrus.

Figure 6.

GABAergic neurons make close contacts (arrows) onto A15 neurons. Confocal images of a section through the A15 of an OVX, E2-treated anestrous ewe processed using dual ICC for TH (green) and GAD67 (red). Scale bar, 20 μm.

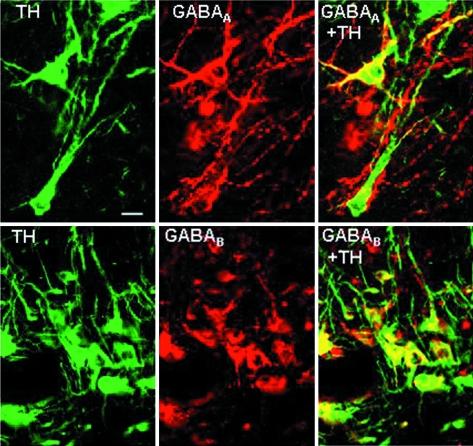

Experiment 7: GABAA receptors on DA neurons

When observed, GABAA receptor immunoreactivity was clearly evident in the cell soma and sometimes extended to the primary dendrites of TH-positive neurons (Fig. 7). All DA cell groups (60–70 cells per group per ewe) examined exhibited coexpression of GABAA receptors, albeit to varying degrees (Table 3). More than 80% of TH-immunoreactive neurons in the A12 coexpressed GABAA receptors, whereas 60% of TH-immunoreactive neurons in the A14 coexpressed GABAA receptors. In contrast, approximately 30% of A15 DA cells contained the GABAA receptor. There was no difference in the percentage of TH-immunoreactive neurons coexpressing GABAA receptors between the breeding season and anestrus (Table 3) in any DA cell population investigated (n = 6 ewes per season).

Figure 7.

A15 neurons contain GABAA (top panels) and GABAB (bottom panels) receptors. Confocal images of a section from the A15 region of an OVX, E2-treated anestrous ewe processed using dual ICC for TH (left panels) and GABAA-Rα1 (top middle panel) or GABAB-R1 (bottom middle panel). Right panels depict computer-generated overlay of other two images illustrating localization of GABAA (top) or GABAB (bottom) receptors in A15 neurons (yellow). Scale bar (top left panel), 20 μm.

Table 3.

Percentage of perikarya containing GABAA-Rα 1 in DA cell groups in anestrus and breeding season

| Anestrus | Breeding season | |

|---|---|---|

| A12 group | 84.7 ± 0.9% | 86.5 ± 1.2% |

| A14 group | 64.2 ± 9.1% | 64.6 ± 5.3% |

| A15 group | 19.9 ± 3.1% | 27.0 ± 3.1% |

Results are shown as mean ± se.

Experiment 8: GABAB receptors on DA neurons

We examined GABAB receptor expression in 53 DA neurons in the A15 group per ewe, 20 DA neurons per ewe in the A14 group, and 27 DA neurons per ewe in the A12 group. Like the GABAA receptor, the GABAB-R1 receptor was evident primarily in TH-positive cell somata (Fig. 7). However, in contrast to GABAA receptors, expression of the GABAB-R1 receptor was observed in almost all (>95%) of the A15 DA neurons (n = 2 ewes). Similar, but slightly lower, expression of the GABAB receptor was observed in A14 (90%) and A12 (79%) DA neurons.

Discussion

The results of these studies provide strong pharmacological and anatomical evidence that GABAergic neurons play an important role in controlling the activity of the A15 DA neurons that mediate E2 negative feedback in anestrous ewes. In contrast, we found no evidence that NO plays a role, because the local administration of NOS inhibitors to the A15 had no effect on LH secretion in the first experiment. It is unlikely that a lack of effect is due solely to an inadequate dose of this inhibitor because the same dose of l-NAME stimulated LH secretion when given to the vmPOA of anestrous ewes in experiments run in parallel with this work (42). Thus, although NO apparently does not act within the RCh to mediate the effects of E2 on A15 neurons, it may play a role elsewhere. In light of these considerations and the effects of GABA receptor agonists, subsequent experiments focused on the possible role of GABA.

Both the GABAA and the GABAB receptor agonist produced a dramatic increase in episodic LH secretion when injected into the A15 of ovary-intact anestrous ewes. These results indicate that GABA can, directly or indirectly, suppress the activity of A15 neurons, which are known to inhibit episodic GnRH secretion during anestrus. It is interesting to note that each agonist increased LH pulse frequency to levels seen in OVX ewes, suggesting that this local treatment completely disrupted E2 negative feedback in ovary-intact ewes. The stimulatory actions of the GABAB antagonist phaclofen and the lack of effect of GABA itself appear in conflict with this interpretation. The former could be due to a nonspecific effect caused by a high concentration of phaclofen produced by the crystalline microimplants used in the first experiment. Alternatively, based on previous work in rams (27,31,43,44), the stimulatory effects of phaclofen could be due to the presence of GABAB autoreceptors on GABA terminals in this region. Because these autoreceptors are thought to be inhibitory, the GABAB receptor blocker may stimulate endogenous GABA release, which would then inhibit A15 neurons via GABAA receptors. The lack of effect of GABA could be due to an insufficient dose or to endogenous systems designed to maintain low extracellular levels of this neurotransmitter. GABA is actively taken up by both neurons and glia, and the presence of GABA autoreceptors would also tend to produce constant extracellular GABA concentrations in response to exogenous GABA. This explanation is supported by reports that exogenously induced increases in GABA concentrations returned to baseline within a few minutes after termination of treatment (45,46); in contrast, the half-life of baclofen (47) and muscimol (48) in the central nervous system are 5 and 2 h, respectively. Thus, despite the negative data with GABA, the potent stimulation of LH secretion produced by the selective GABA receptor agonists, together with the anatomical evidence for GABA receptors on A15 neurons, supports the hypothesis that inhibitory GABA input contributes to the control of A15 neuronal activity.

If GABAergic input mediates the stimulatory actions of E2 on A15 neurons, then E2 must inhibit the release of GABA from these afferents. One would thus predict that endogenous GABA release is low in ovary-intact ewes and that GABA levels rise after OVX; this OVX-induced rise in GABAergic tone would then inhibit A15 neural activity and allow episodic GnRH and LH secretion to increase. The dramatic increase in LH pulses produced by the GABA agonists in ovary-intact ewes is consistent with low endogenous GABA concentrations when E2 is present because it indicates the presence of free receptors available to interact with the exogenous GABA agonists. Based on similar logic, one can infer that GABA release is elevated after OVX because the agonists failed to increase LH pulse frequency in these animals. One could argue that agonists were ineffective because pulse frequency is already maximal in these OVX ewes, but this is unlikely because LH pulse frequency in OVX anestrous animals can be further increased by photoperiodic (49) or other pharmacological (50,51) manipulations. Thus, the changes in response to GABA agonists with endocrine condition provide indirect evidence that endogenous GABA release is inhibited by E2 during anestrus.

The inhibitory effects of the combination of GABAA and GABAB receptor antagonists further support the hypothesis that endogenous GABA is inhibiting A15 neural activity in OVX ewes. However, this system appears to be quite resistant to GABAergic blockade. Neither GABA receptor antagonist alone produced any inhibitory effect, and the combination produced a strong inhibition of LH only when injected in the middle of the A15. The former is consistent with the presence of both GABAA and GABAB receptors on A15 neurons, and the latter suggests that it is necessary to block GABA inhibition of a majority of A15 neurons to release sufficient DA to inhibit GnRH secretion. This resistance to GABA blockade could reflect either a high level of endogenous GABA release in the region of the A15 neurons or a decrease in responsiveness of GnRH neurons to inhibitory inputs that is known to occur in chronically OVX animals (52,53). Taken together, these pharmacological studies provide strong support for the hypothesis that in anestrus, E2 negative feedback is mediated, at least in part, by the suppression of GABA release from afferents to the A15 DA neurons.

One potential problem in interpreting studies involving local administration of receptor agonists and antagonists to a ubiquitous neurotransmitter, such as GABA, is the possibility that any effects observed may be due to diffusion from the injection site. Although this is difficult to directly address without a detailed knowledge of local concentrations of endogenous GABA, levels of receptor ligands produced by microinjections and receptor affinities, there are several lines of evidence indicating that the drugs acted locally in the A15 in these experiments. First, missed injections of agonists produced no stimulatory effect in ovary-intact ewes even though they were within 1–1.5 mm of the A15. Similarly, the effectiveness of combined GABAA and GABAB receptor antagonists when administered to the middle, but not the rostral or caudal portion, of the A15 argues strongly for minimal effective spread of these drugs. Third, local administration to the ventromedial nucleus of GABAA (54) or GABAB (55) receptor agonists either suppressed (54) or had no effect (55) on GnRH/LH secretion in anestrous ewes. Because neither of these results were observed with A15 microinjections of GABA receptor agonists, these drugs are unlikely to have diffused from the A15 to the ventromedial nucleus. Finally, the anatomical observations demonstrate that the receptors are present on A15 DA neurons for local actions of both GABAA and GABAB receptor agonists and antagonists.

The observation that every TH-immunoreactive neuron within the A15 group received at least one close contact containing GAD67 provides strong evidence that the activity of these neurons is under the direct control of GABAergic afferents. Comparison of the mean number of GAD-positive close contacts with previous data on the total number of synapsin-containing close contacts (37) on to A15 neurons indicates that GABAergic input represents 25–30% of afferents to these neurons. Similarly, the presence of GABAB-R1 receptors in 99% of A15 neurons indicates that these neurons can respond to GABA released from these afferents. Somewhat surprisingly, a much smaller percentage of A15 neurons expressed the GABAA-Rα1 subunit. This low level is unlikely to be due to technical difficulties because receptor expression was evident in some, but not other, A15 neurons in the same section (Fig. 7), and a much higher level of expression was observed in both A14 and A12 DA neurons. The latter is consistent with evidence that local administration of GABAergic ligands in the vicinity of A12 neurons alters prolactin secretion in sheep (56). These data, of course, do not rule out the possibility that A15 neurons contain a different isoform of the α-subunit; the robust effects of the GABAA receptor agonist suggest either that this is the case or that the subset of A15 DA neurons containing GABAA-Rα1 are dedicated to inhibition of GnRH neurons.

Although these data provide anatomical support for direct effects of GABA on A15 neurons, they do not rule out the possibility of indirect actions of this neurotransmitter. There are clearly many GAD-positive varicosities within the A15 area that do not synapse on TH-containing neurons (Fig. 6). Thus, the GABA agonist could be acting via local interneurons. The relatively long delay (46–69 min) between microinjection of the GABA agonists and the first LH pulse in ovary-intact ewes is consistent with this possibility.

In addition to mediating E2 negative feedback during anestrus, one other key property of A15 neurons is their seasonal nature; E2 stimulates them in anestrus but not the breeding season (10,11,12). This characteristic largely accounts for the seasonal changes in response to E2 negative feedback in the ewe (4,5,6,7) and may reflect seasonal differences in afferent input to these neurons (37). The lack of a seasonal change in GAD-positive close contacts and expression of GABAA receptors on A15 neurons and the high percentage of these neurons containing GABAB receptors in anestrus suggest that an increase in GABAergic afferents or increased responsiveness of A15 neurons to GABA may not play a major role in the suppression of A15 activity in the breeding season. This, of course, does not preclude an important functional change in this inhibitory input. For example, a simple explanation of the seasonal changes in response to E2 negative feedback would be the loss of ERα in GABAergic afferents during the breeding season. If this occurred, E2 would no longer be able to inhibit GABAergic tone so that A15 neurons would be inactive regardless of circulating E2 concentrations, thus producing the loss of response to E2 negative feedback in the breeding season. A test of this attractive hypothesis awaits procedures for identifying the GABAergic cell bodies afferent to the A15 neurons, for example, by combining retrograde tract tracing from the A15 with in situ hybridization for GAD. It is also possible that seasonal changes in other A15 afferents are more critical than changes in GABAergic tone. Glutamatergic neurons also synapse on to A15 neurons and appear to participate in E2 negative feedback in anestrus (57). Moreover, preliminary work indicates that an increase in stimulatory glutamatergic tone may occur in anestrus because the number of glutamatergic close contacts on to A15 neurons is higher at this time of year (58).

An important role for GABA in steroid negative feedback has previously been proposed for rats (59,60,61), sheep (27,29,30,44,62), and primates (63,64,65). In most other systems, however, GABA has been proposed to exert its effects directly on GnRH neurons, not indirectly via another set of inhibitory neurons. Although there is strong evidence for such a role in male rodents (60,61), the data in many other models are difficult to interpret because both receptor agonists and antagonists inhibit LH secretion (29,66,67), paradoxical stimulatory effects of GABAB receptor agonists are sometimes observed (27,55,56), and there is considerable controversy as to whether GABA inhibits (68) or stimulates (69) GnRH neurons in adult rodents. Perhaps the closest parallel to the anestrous ewe is the rhesus monkey in which it has been proposed that GABA mediates the enhanced negative feedback action of E2 before puberty, with a decrease in GABAergic tone contributing to the onset of the menarche (63,64,65). Interestingly, as may be the case in the ewe, reciprocal changes in glutamatergic and GABAergic input may both be involved in the onset of reproductive function in female rhesus monkeys. It is important to point out, however, that because GABA and glutamate appear to act indirectly via inhibitory A15 neurons in the ewe, any changes would be the inverse of those in the primate (i.e. low GABAergic and high glutamatergic tone induces infertility in sheep).

In conclusion, the results of these studies provide strong evidence that GABAergic afferents to A15 DA neurons participate in E2 negative feedback in anestrous ewes. The pharmacological data suggest that GABA inhibits A15 activity and that GABAergic tone is in turn suppressed by E2 to stimulate A15 neurons, which then inhibit GnRH secretion. The anatomical data demonstrate that A15 neurons receive GABA input and have the receptors to respond to this neurotransmitter. However, this anatomical input does not appear to change with season. Whether seasonal changes in GABAergic tone are important to the seasonal variation in A15 responsiveness to E2 awaits further study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Karie Hardy and Heather Clemmer at the West Virginia University Food Animal Research Facility for care of animals and Paul Harton for his technical assistance in sectioning tissue. We also thank Dr. Al Parlow and the National Hormone and Peptide Program for reagents used to measure LH and the West Virginia University Image Analysis Center for use of their confocal microscope.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 HD17864.

The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online March 6, 2008

Abbreviations: DA, Dopaminergic; E2, estradiol; ER, estrogen receptor; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; GABAB-R1, GABAB receptor-1; GABAA-Rα1, GABAA receptor α; GAD67, glutamic acid decarboxylase 67; ICC, immunocytochemical; l-NAME, NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester; NOS, nitric oxide synthase; OVX, ovariectomy; PB, phosphate buffer; RCh, retrochiasmatic; RT, room temperature; SMTC, S-methyl thiocitrulline; TH, tyrosine hydroxylase; TxBS, Triton X-100 in buffered saline; vmPOA, ventromedial preoptic area.

References

- Plant TM, Witchel SF 2006 Puberty in nonhuman primates and humans. In: Neill JD, ed. Knobil and Neill’s physiology of reproduction, 3rd ed. Vol 2. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2177–2232 [Google Scholar]

- McNeilly AS 2006 Suckling and the control of gonadotropin secretion. In: Neill JD, ed. Knobil and Neill’s physiology of reproduction, 3rd ed. Vol 2. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2511–2552 [Google Scholar]

- Goodman RL 1999 Seasonal reproduction, mammals In: Knobil E, Neill JD, eds. Encyclopedia of reproduction. Vol 4. San Diego: Academic Press; 341–351 [Google Scholar]

- Malpaux B 2006 Seasonal Regulation of Reproduction in Mammals. In: Neill JD, ed. Knobil and Neill’s physiology of reproduction, 3rd ed. Vol 2. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2231–2282 [Google Scholar]

- Goodman RL, Inskeep EI 2006 Neuroendocrine control of the ovarian cycle of the sheep. In: Neill JD, ed. Knobil and Neill’s physiology of reproduction, 3rd ed. Vol 2. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2389–2447 [Google Scholar]

- Karsch FJ 1987 Central actions of ovarian steroids in the feedback regulation of pulsatile secretion of luteinizing hormone. Annu Rev Physiol 49:365–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiery JC, Gayrard V, Le Corre S, Viguie C, Martin GB, Chemineau P, Malpaux B 1995 Dopaminergic control of LH secretion by the A15 nucleus in anoestrous ewes. J Reprod Fertil Suppl 49:285–296 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiery JC, Martin GB, Tillet Y, Caldani M, Quentin M, Jamain C, Ravault JP 1989 Role of hypothalamic catecholamines in the regulation of luteinizing hormone and prolactin secretion in the ewe during seasonal anestrus. Neuroendocrinology 49:80–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havern RL, Whisnant CS, Goodman RL 1994 Dopaminergic structures in the ovine hypothalamus mediating estradiol negative feedback in anestrous ewes. Endocrinology 134:1905–1914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayrard V, Malpaux B, Tillet Y, Thiery JC 1994 Estradiol increases tyrosine hydroxylase activity of the A15 nucleus dopaminergic neurons during long days in the ewe. Biol Reprod 50:1168–1177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman MN, Durham DM, Jansen HT, Adrian B, Goodman RL 1996 Dopaminergic A14/A15 neurons are activated during estradiol negative feedback in anestrous, but not breeding season, ewes. Endocrinology 137:4443–4450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman RL, Thiery JC, Delaleu B, Malpaux B 2000 Estradiol increases multi-unit electrical activity in the A15 area of ewes exposed to inhibitory photoperiods. Biol Reprod 63:1352–1357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman MN, Karsch FJ 1993 Do gonadotropin-releasing hormone, tyrosine hydroxylase, and β-endorphin-immunoreactive neurons contain estrogen receptors? A double-label immunocytochemical study in the Suffolk ewe. Endocrinology 133:887–895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner DC, Herbison AE 1997 Effects of photoperiod on estrogen receptor, tyrosine hydroxylase, neuropeptide Y, and β-endorphin immunoreactivity in the ewe hypothalamus. Endocrinology 138:2585–2595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubbers LS, Greco B, Hileman SM, Schwartz PE, Blaustein JD 1999 Localization of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and estrogen receptor (ER) β in the retrochiasmatic region of the hypothalamus of female sheep. Soc Neurosci Abstr 25:1452 [Google Scholar]

- Lehman MN, Coolen LM, Goodman RL, Viguie C, Billings HJ, Karsch FJ 2002 Seasonal plasticity in the brain: the use of large animal models for neuroanatomical research. Reprod Suppl 59:131–147 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson GM, Connors JM, Hardy SL, Valent M, Goodman RL 2001 Oestradiol microimplants in the ventromedial preoptic area inhibit secretion of luteinizing hormone via dopamine neurones in anoestrous ewes. J Neuroendocrinol 13:1051–1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallegos-Sanchez J, Delaleu B, Caraty A, Malpaux B, Thiery JC 1997 Estradiol acts locally within the retrochiasmatic area to inhibit pulsatile luteinizing hormone release in the female sheep during anestrus. Biol Reprod 56:1544–1549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy SL, Anderson GM, Valent M, Connors JM, Goodman RL 2003 Evidence that estrogen receptor α, but not β, mediates seasonal changes in the response of the ovine retrochiasmatic area to estradiol. Biol Reprod 68:846–852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbison AE, Robinson JE, Skinner DC 1993 Distribution of estrogen receptor-immunoreactive cells in the preoptic area of the ewe: co-localization with glutamic acid decarboxylase but not luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone. Neuroendocrinology 57:751–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pompolo S, Pereira A, Scott CJ, Fumino F, Clarke IJ 2003 Evidence for estrogenic regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons by glutamatergic neurons in the ewe brain: an immunocytochemical study using an antibody against vesicular glutamate transporter-2. J Comp Neurol 465:136–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufourny L, Skinner DC 2002 Influence of estradiol on NADPH diaphorase-neuronal nitric oxide synthase activity and colocalization with progesterone or type II glucocorticoid receptors in ovine hypothalamus. Biol Reprod 67:829–836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman RL, Coolen LM, Anderson GM, Hardy SL, Valent M, Connors J, Fitzgerald ME, Lehman MN 2004 Evidence that dynorphin plays a major role in mediating progesterone negative feedback on gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons in sheep. Endocrinology 145:2959–2967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schillo KK, Kuehl D, Jackson GL 1985 Do endogenous opioid peptides mediate the effects of photoperiod on release of luteinizing hormone and prolactin in ovariectomized ewes? Biol Reprod 32:779–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K, Haynes NB, Lamming GE, Brooks AN 1988 Ovarian steroid hormone involvement in endogenous opioid modulation of LH secretion in mature ewes during the breeding and non-breeding seasons. J Reprod Fertil 83:129–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbison AE 2006 Physiology of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuronal network. In: Neill JD, ed. Knobil and Neill’s physiology of reproduction, 3rd ed. Vol 2. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1415–1482 [Google Scholar]

- Jackson GL, Kuehl D 2002 γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) regulation of GnRH secretion in sheep. Reprod Suppl 59:15–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brann DW, Mahesh VB 1997 Excitatory amino acids: evidence for a role in the control of reproduction and anterior pituitary hormone secretion. Endocr Rev 18:678–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott CJ, Clarke IJ 1993 Inhibition of luteinizing hormone secretion in ovariectomized ewes during the breeding season by γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is mediated by GABA-A receptors, but not GABA-B receptors. Endocrinology 132:1789–1796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott CJ, Clarke IJ 1993 Evidence that changes in the function of the subtypes of the receptors for γ-amino butyric acid may be involved in the seasonal changes in the negative-feedback effects of estrogen on gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion and plasma luteinizing hormone levels in the ewe. Endocrinology 133:2904–2912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira SA, Scott CJ, Kuehl D, Jackson GL 1996 Differential regulation of luteinizing hormone release by γ-aminobutyric acid receptor subtypes in the arcuate-ventromedial region of the castrated ram. Endocrinology 137:3453–3460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomaszewska-Zaremba D, Mateusiak K, Przekop F 2002 The involvement of GABAA receptors in the control of GnRH and β-endorphin release, and catecholaminergic activity in the preoptic area in anestrous ewes. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 110:336–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunyady B, Krempels K, Harta G, Mezey E 1996 Immunohistochemical signal amplification by catalyzed reporter deposition and its application in double immunostaining. J Histochem Cytochem 4:1353–1362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sliwowska JH, Billings HJ, Goodman RL, Lehman MN 2006 Immunocytochemical colocalization of GABA-B receptor subunits in gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons of the sheep. Neuroscience 141:311–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen HT, Cutter CT, Hardy S, Lehman MN, Goodman RL 2003 Seasonal plasticity in the GnRH system of the ewe: changes in identified GnRH inputs and in glial association. Endocrinology 144:3663–3676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher MJ, Song L, Fazal Arain F, Macdonald RL 2004 The juvenile myoclonic epilepsy GABAA receptor α1 subunit mutation A322D produces asymmetrical, subunit position-dependent reduction of heterozygous receptor currents and α1 subunit protein expression. J Neurosci 24: 5570–5578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams VL, Goodman RL, Salm AK, Coolen LM, Karsch FJ, Lehman MN 2006 Morphological plasticity in the neural circuitry responsible for seasonal breeding in the ewe. Endocrinology 147:4843–4851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman RL, Karsch FJ 1980 Pulsatile secretion of luteinizing hormone: differential suppression by ovarian steroids. Endocrinology 107:1286–1290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RA, Mitchell R 1985 Evidence for GABAB autoreceptors in median eminence. Eur J Pharmacol 118:355–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson GL, Kuehl D 2002 The GABAB antagonist CGP 52432 attenuates the stimulatory effect of the GABAB agonist SKF 97541 on luteinizing hormone secretion in the male sheep. Exp Biol Med 227:315–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza M, Fassio A, Gemignani A, Bonanno G, Raiteri M 1993 CGP52432: a novel potent and selective GABA-B autoreceptor antagonist in rat cerebral cortex. Eur J Pharmacol 237:191–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus CJ, Hardy SL, Valent M, Goodman RL 2007 Does nitric oxide act in the ventromedial preoptic area to mediate oestrogen negative feedback in the seasonally anoestrous ewe? Reproduction 134:137–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira SA, Hileman SM, Kuehl DE, Jackson GL 1998 Effects of dialyzing γ-aminobutyric acid receptor antagonists into the medial preoptic and arcuate ventromedial region on luteinizing hormone release in male sheep. Biol Reprod 58:1038–1046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson GL, Wood SG, Kuehl D 2000 A γ-aminobutyric acid B agonist reverses the negative feedback effect of testosterone on gonadotropin-releasing hormone and luteinizing hormone secretion in the male sheep. Endocrinology 141:3940–3945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinker CC, Bowser MT 2007 4-Fluoro-7-nitro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazole as a fluorogenic labelling reagent for the in vivo analysis of amino acid neurotransmitters using online microdialysis-capillary electrophoresis. Anal Chem 79:874–8754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JE 1995 γ-Amino-butyric acid and the control of GnRH secretion in sheep. J Reprod Fertil Suppl 49:221–230 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn RD, Kroin JS 1987 Long-term intrathecal baclofen infusion for treatment of spasticity. J Neurosurg 66:181–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews WD, Intoccia AP, Osborne VL, McCafferty GP 1981 Correlation of [14C]muscimol concentration in rat brain with anticonvulsant activity. Eur J Pharmacol 69:249–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JE, Radford HM, Karsch FJ 1985 Seasonal changes in pulsatile luteinizing hormone (LH) secretion in the ewe: relationship of frequency of LH pulses to daylength and response to estradiol negative feedback. Biol Reprod 33:324–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer SL, Goodman RL 1986 Separate neural systems mediate the steroid-dependent and steroid-independent suppression of tonic luteinizing hormone secretion in the anestrous ewe. Biol Reprod 35:562–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisnant CS, Goodman RL 1990 Further evidence that serotonin mediates the steroid-independent inhibition of luteinizing hormone secretion in anestrous ewes. Biol Reprod 42:656–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsch FJ, Legan SJ, Hauger RL, Foster DL 1977 Negative feedback action of progesterone on tonic luteinizing hormone secretion in the ewe: dependence on the ovaries. Endocrinology 101:800–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery GW, Martin GB, Pelletier J 1985 Changes in pulsatile LH secretion after ovariectomy in Ile-de-France ewes in two seasons. J Reprod Fertil 73:173–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomaszewska-Zaremba D, Przekop F, Mateusiak K 2001 The involvement of GABAA receptors in the control of GnRH and β-endorphin release, and catecholaminergic activity in the ventromedial-infundibular region of hypothalamus in anestrous ewes. J Physiol Pharmacol 52:489–500 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson GL, Kuehl D 2004 Effects of applying γ-aminobutyric acid (B) drugs into the medial basal hypothalamus on basal luteinizing hormone concentrations and on luteinizing hormone surges in the female sheep. Biol Reprod 70:334–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira SA, Browning DA, Scott CJ, Kuehl DE, Jackson GL 1998 Effect of infusing γ-aminobutyric acid receptor agonists and antagonists into the medial preoptic area and ventromedial hypothalamus on prolactin secretion in male sheep. Endocrine 9:303–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman RL, Singh SR, Valent M, Connors JM, McManus CJ 2006 Glutamate input to A15 neurons may mediate estradiol negative feedback in anestrous ewes. Front Neuroendocrinol 27:65 (Abstract 123) [Google Scholar]

- Singh SR, McManus CJ, Coolen LM, Lehman MN, Goodman RL 2006 Glutamate input to A15 dopamine neurons increases in anestrous ewes. Front Neuroendocrinol 27:75 (Abstract 146) [Google Scholar]

- Herbison AE, Heavens RP, Dye S, Dyer RG 1991 Acute action of oestrogen on medial preoptic gamma-aminobutyric acid neurons: correlation with oestrogen negative feedback on luteinising hormone secretion. J Neuroendocrinol 3:101–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratton DR, Selmanoff M 1994 Castration-induced decrease in the activity of medial preoptic and tuberinfundibular GABAergic neurons is prevented by testosterone. Neuroendocrinology 60:141–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo MJ, Searles RV, He JR, Shen W, Grattan DR, Selmanoff M 2000 Castration rapidly decreases hypothalamic γ-aminobutyric acidergic neuronal activity in both male and female rats. Brain Res 878:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JE, Kendrick KM 1992 Inhibition of luteinising hormone secretion in the ewe by progesterone: associated changes in the release of γ-aminobutyric acid and noradrenaline in the preoptic area as measured by intracranial microdialysis. J Neuroendocrinol 4:231–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsushima D, Hel DL, Terasawa E 1994 γ-Aminobutyric acid is an inhibitory neurotransmitter restricting the release of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone before the onset of puberty. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91:395–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasuya E, Nyberg CL, Mogi K, Terasawa E 1999 A role of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glutamate in control of puberty in female rhesus monkeys: effects of an antisense oligodeoxynucleotide for GAD67 messenger ribonucleic acid and MK801 on luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone release. Endocrinology 140:705–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terasawa E, Luchansky LL, Kasuya E, Nyberg CL 1999 An increase in glutamate release follows a decrease in γ-aminobutyric acid and the pubertal increase in luteinizing hormone releasing hormone release in female rhesus monkeys. J Neuroendocrinol 11:275–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbison AE, Champman C, Dyer RG 1991 Role of medial preoptic GABA neurons in regulating luteinizing hormone secretion in the ovariectomized rat. Exp Brain Res 87:345–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarry H, Leonhardt S, Wuttke W 1991 γ-Aminobutyric acid neurons in the preoptic/anterior hypothalamic area synchronize the phasic activity of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulse generator in ovariectomized rats. Neuroendocrinology 53:261–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han SK, Todman MG, Herbison AE 2004 Endogenous GABA release inhibits the firing of adult gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Endocrinology 145:495–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defazio RA, Heger S, Ojeda SR, Moenter SM 2002 Activation of A-type γ-aminobutyric acid receptors excites gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Mol Endocrinol 16:2872–2891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]