Abstract

A single mossy fiber input contains several release sites and is located on the proximal portion of the apical dendrite of CA3 neurons. It is, therefore, well suited to exert a strong influence on pyramidal cell excitability. Accordingly, the mossy fiber synapse has been referred to as a detonator or teacher synapse in autoassociative network models of the hippocampus. The very low firing rates of granule cells [Jung, M. W. & McNaughton, B. L. (1993) Hippocampus 3, 165–182], which give rise to the mossy fibers, raise the question of how the mossy fiber synapse temporally integrates synaptic activity. We have therefore addressed the frequency dependence of mossy fiber transmission and compared it to associational/commissural synapses in the CA3 region of the hippocampus. Paired pulse facilitation had a similar time course, but was 2-fold greater for mossy fiber synapses. Frequency facilitation, during which repetitive stimulation causes a reversible growth in synaptic transmission, was markedly different at the two synapses. At associational/commissural synapses facilitation occurred only at frequencies greater than once every 10 s and reached a magnitude of about 125% of control. At mossy fiber synapses, facilitation occurred at frequencies as low as once every 40 s and reached a magnitude of 6-fold. Frequency facilitation was dependent on a rise in intraterminal Ca2+ and activation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II, and was greatly reduced at synapses expressing mossy fiber long-term potentiation. These results indicate that the mossy fiber synapse is able to integrate granule cell spiking activity over a broad range of frequencies, and this dynamic range is substantially reduced by long-term potentiation.

One of the most remarkable features of chemically transmitting synapses is their sensitivity to prior activation. This plasticity is postulated to play a fundamental role in behaviors ranging from cortical arousal (e.g., the augmenting response) (1, 2) to learning and memory (3, 4). At many central nervous system synapses this use dependent modification has both short- and long-term manifestations. On the short time scale low frequency stimulation can result in a reversible increase in the response referred to as frequency facilitation. At the other extreme brief high frequency stimulation can result in a lasting increase in synaptic strength, referred to as long-term potentiation (LTP). In the hippocampus most excitatory synapses show frequency dependent facilitation within stimulus intervals of a few tens to hundreds of milliseconds. Such temporal integration of synaptic activity is believed to play a fundamental role in information processing because it allows the nervous system to be instructed by the temporal pattern of activity of a given input (5).

How does temporal synaptic integration occur at terminals of neurons that normally fire at extremely low rates, such as hippocampal granule cells? This question was addressed by studying frequency dependent facilitation at mossy fiber synapses, which in striking contrast to the associational/commissural (assoc/com) synapse exhibit temporal integration starting with frequencies as low as 0.025 Hz. We have investigated the mechanism of this short-term plasticity and the consequences that this plasticity might have on information processing in the CA3 region of the hippocampus.

METHODS

Standard procedures were used to prepare hippocampal slices (400–500 μm) from 5- to 15-day-old guinea pigs. Slices were maintained at room temperature for at least 1 h in a submerged chamber containing artificial cerebrospinal fluid equilibrated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 and then transferred to a superfusing chamber. The artificial cerebrospinal fluid contained 119 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 1 mM NaH2PO4, 1.3 mM MgSO4, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 26 mM NaHCO3, and 11 mM glucose. For electrophysiological recording, the concentrations of CaCl2 and MgSO4 were raised to 4 mM. Whole cell recordings were performed at room temperature in the presence of picrotoxin (100 μM). Whole cell recording electrodes were filled with a solution containing 122.5 mM Cs gluconate, 10 mM CsCl, 10 mM Hepes, 10 mM bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetate (BAPTA), 8 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgATP and 0.3 mM Na3GTP, pH 7.4. The resistance of the patch pipette ranged between 2 and 4 MΩ. Access resistances ranged between 4 and 10 MΩ and were not allowed to vary by more than 15% during the course of the experiment. No series resistance compensation was used. N-Methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor-mediated excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) were recorded at a holding potential of +30 to +40 mV in the presence of 2,3-hydroxy-6-nitro-7-sulfamoylbenzo[f]quinoxaline (NBQX) (10 μM). α-Amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor-mediated EPSCs were recorded at a holding potential of −60 to −70 mV in the presence of 100–400 nM 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX) to avoid epileptiform activity. Two glass electrodes containing 1 M NaCl were placed in the stratum lucidum and stratum radiatum to record evoked mossy fiber and assoc/com field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs), respectively, in the absence of picrotoxin and NBQX. Bipolar tungsten electrodes were placed in the cell-body layer of the granule cells for mossy fiber stimulation and in the radiatum for assoc/com stimulation. At the end of all field experiments 20 μM CNQX was added to the bath to assess the fiber volley component of the mossy fiber fEPSPs. Data were acquired and analyzed as described (6). Average values are expressed as mean ± SEM. KN62 was diluted in dimethyl sulfoxide (final concentration, 0.1%). Dimethyl sulfoxide had no effect on frequency facilitation. The drugs used were as follows: KN62 (LC Services, Woburn, MA) KT 5720 (Calbiochem), nimodipine (Research Biochemicals, Natick, MA), cesium hydroxide, d-gluconic acid (Aldrich), picrotoxin, BAPTA, l-AP4 (Sigma), CNQX, NBQX, (+)-MCPG, d-AP5 (Tocris Cookson) and, EGTA-AM (Molecular Probes).

RESULTS

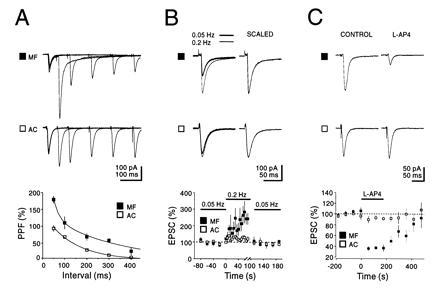

Mossy fiber and assoc/com synaptic responses differ from each other in a number of striking ways (Fig. 1). Although both types of synapses show a PPF of similar duration, the magnitude of PPF at mossy fiber synapses was ≈2-fold greater (Fig. 1A). A second distinguishing feature of mossy fiber responses was their sensitivity to repetitive stimulation. Changing the frequency of stimulation from 0.05–0.2 Hz resulted in a greater than 2-fold reversible increase in the size of the mossy fiber response, but only a 20% increase in the assoc/com responses (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, the effect of increasing the stimulus frequency developed slowly over about a 20-s period. Finally, the mossy fiber responses, but not the assoc/com responses, in the guinea pig are inhibited presynaptically by the metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist l-AP4 (Fig. 1C) (7, 8). In all subsequent experiments l-AP4 was applied to assess the purity of the mossy fiber response and inputs were used only if the inhibition was at least 60% for EPSCs and 80% for field EPSPs. In addition in many experiments we monitored the mossy fiber NMDA receptor-mediated component of the EPSC in the presence of CNQX, to eliminate the possibility of polysynaptic contamination (6).

Figure 1.

Physiological and pharmacological distinction between AMPA-receptor EPSCs evoked by stimulation of mossy fibers and associational/commissural fibers. (A) The mossy fiber (MF) synapse exhibits a greater paired pulse facilitation (PPF) than the assoc/com (AC) synapse. Current traces: superimposed sweeps with five different interstimulus intervals. Note the long-lasting tail, specific for mossy fiber EPSCs. This component is not due to voltage clamp error and is characterized elsewhere (P. Castillo, personal communication). The graph shows the average PPF plotted against interstimulus intervals (n = 6). The points for the assoc/com synapse were fitted with a single exponential (t = 133 ms), while the points for the mossy fiber synapses were fitted with a double exponential (t1 = 27 ms, t2 = 301 ms). PPF was defined as [(p2 − p1)/p1] × 100, where p1 and p2 are the amplitude of the EPSCs evoked by the first and second pulse, respectively. (B) Frequency facilitation of mossy fiber responses. Current traces: superimposed averaged EPSCs evoked at two different stimulation frequencies (0.05 and 0.2 Hz). The graph summarizes the results of six experiments. Note the slow build up of facilitation at the mossy fiber synapse as well as the complete reversal upon returning to the control stimulation frequency. (C) Activation of presynaptic group three metabotropic glutamate receptors by l-AP4 (10 μM) selectively depresses mossy fiber transmission. The graph summarizes the results of eight experiments. For each of the three sets of experiments in A–C the current traces shown for mossy fiber and assoc/com were recorded from the same CA3 neurons voltage clamped at −70 mV.

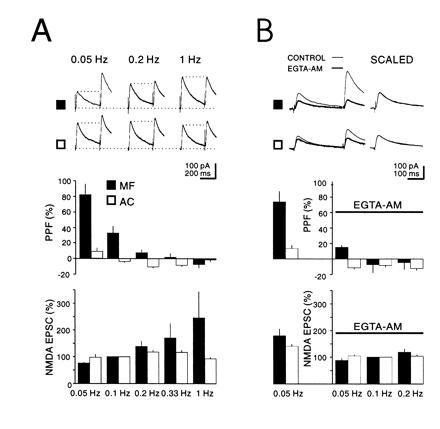

The frequency facilitation was not simply an accumulation of the facilitation seen with PPF, because the interpulse intervals that showed frequency facilitation were much greater than the maximal interval required for PPF. Additionally facilitation decays with a time course of 20–40 s, two orders of magnitude larger than the decay of PPF. However, PPF and frequency facilitation did interact (Fig. 2A). At the mossy fiber synapse as the frequency at which paired pulses (300-ms interpulse interval) was delivered was increased from 0.05–1 Hz, PPF decreased and at 1 Hz disappeared. Accompanying the loss of PPF was the usual frequency facilitation of the response to the first pulse. The simultaneously monitored assoc/com synapses were much less sensitive both to the increase in stimulation frequency and the effects that this had on PPF.

Figure 2.

Frequency facilitation of mossy fiber NMDA receptors EPSCs is accompanied by a decrease in PPF and is dependent on intraterminal Ca2+. (A) Current traces: NMDA receptors EPSCs evoked by stimulation of mossy fibers (MF) (▪) and assoc/com inputs (AC) (□). PPF was evoked at a fixed interstimulus interval (300 ms), while the stimulation rate was varied as indicated. The graphs summarize six experiments where stimulation frequency is plotted against PPF (Upper) or p1 (Lower) for both mossy fibers and assoc/com synapses. Note the correlation between the increase in p1 and the decrease in PPF for the mossy fiber synapse. Note also that at 1 Hz PPF is the same for both terminals. (B) Current traces show that EGTA-AM (200 μM) depresses p2 more than p1 thus decreasing PPF. Graphs summarize the results from five experiments. The columns to the left of the ordinate indicate control values for PPF and p1 at a stimulus frequency of 0.05 Hz before EGTA-AM application and on the right of the ordinate after EGTA-AM application for several stimulation frequencies. The averaged values for p1 were normalized to 0.1 Hz. CA3 neurons were voltage clamped at +40 mV.

At peripheral synapses it has been proposed that Ca2+ is involved in PPF and frequency facilitation (9). More specifically at mossy fiber synapses, Ca2+ imagining studies have found a correlation with the rise in intraterminal Ca2+ and frequency facilitation (10). We therefore examined the effects of buffering intraterminal Ca2+ on PPF and frequency facilitation (Fig. 2B). Application of the membrane-permeant Ca2+ chelator EGTA-AM (200 μM), which decreased the size of responses to both inputs by ≈40% (at 0.5 Hz), virtually blocked PPF. In addition, the frequency facilitation, at least at <0.2 Hz, was strongly reduced. At higher frequencies the reduction was less evident, presumably because the large influx of Ca2+ saturated the available buffer. Similar results to those obtained on NMDA receptors EPSCs were also obtained with the AMPA receptor EPSCs (Fig. 3). In these experiments the responses to two frequencies were recorded before and after the addition of EGTA-AM for 15–30 min. The interaction of PPF and frequency facilitation suggest that they share a common mechanism. Because changes in postsynaptic Ca2+ were prevented by including 10 mM BAPTA in the whole cell pipette solution, the effects of EGTA-AM indicate that both processes also require a rise in intraterminal Ca2+.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the action of EGTA-AM (200 μM) on PPF and frequency facilitation at two different frequencies on AMPA receptor-mediated EPSCs normalized to 0.1 Hz before EGTA-AM application (n = 4).

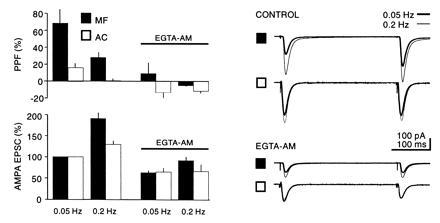

The long-lasting effect of prior synaptic activation (e.g., ≈80 s) suggests that some intermediary biochemical reaction is necessary for Ca2+ to exert its effect on transmitter release. The Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CaM kinase II) is a ubiquitous Ca2+ activated enzyme, known to be present in the presynaptic terminal. We have therefore examined the effects of the CaM kinase II selective inhibitor KN62 on frequency facilitation. Since the magnitude of the frequency facilitation varied considerably between experiments it was important to obtain control responses before the application of KN62. A single experiment is shown in Fig. 4A, in which the stimulus frequency is increased in a series of steps. KN62 was then applied and the series of frequencies repeated after 60 min. KN62 had no effect on baseline responses evoked at low frequencies, but considerably reduced the responses at higher frequencies. A summary of five experiments (Fig. 4C) shows the percent decrease of the responses at each frequency during KN62. In contrast KN62 in these same experiments had no effect on mossy fiber LTP (Fig. 4D). It has been proposed that a Ca2+/calmodulin-sensitive adenylyl cyclase is involved in the generation of mossy fiber LTP (11). It was therefore of interest to determine if an inhibitor of the cAMP cascade also blocked frequency facilitation. We used KT5720, an inhibitor of the catalytic site of protein kinase A that inhibits mossy fiber LTP (11, 12). As shown in Fig. 4E, KT5720 had no effect on frequency facilitation.

Figure 4.

Frequency facilitation is attenuated by the CaM kinase II inhibitor KN62. (A) The amplitude of mossy fiber fEPSPs evoked at various stimulation frequencies before and during application of KN62 (3.5 μM). Arrows indicate changes in stimulation frequencies (successively 0.05 Hz, 0.0125 Hz, 0.025 Hz, 0.05 Hz, 0.1 Hz, 0.2 Hz, and 0.33 Hz). Note the reduction in facilitation after KN62 incubation. (B) Summary graph of frequency facilitation evoked at various stimulation frequencies for mossy fiber and assoc/com fEPSPs normalized to 0.0125 Hz (n = 5). Note that varying stimulation frequency, even within the range of very low frequencies, induces significant changes in mossy fiber fEPSPs. (C) Summary graph of the difference in frequency facilitation before and during application of KN62 for mossy fibers and assoc/com fEPSPs (n = 5). A significant reduction in facilitation (P < 0.02, two-tailed paired Student’s t test) was observed for mossy fiber fEPSPs at frequencies higher than 0.1 Hz. KN62 had no significant effect on baseline transmission or the assoc/com responses. (D) KN62 has no effect on mossy fiber LTP (n = 5). LTP was first induced on a control mossy fiber input in the absence of KN62 by four 1-s tetani at 100 Hz with 20-s intervals in the presence of d-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (50 μM) (○). Sixty minutes after the induction of LTP, KN62 (3.5 μM) was bath applied for at least 1 h, and an identical LTP inducing protocol was applied to a second independent mossy fiber pathway (•). The typical decaying phase of mossy fiber LTP is increased due to the elevated concentration of external Ca2+. (Similar results were obtained in the presence of 2.5 mM external Ca2+; n = 2.) (E) Summary graph showing no significant difference in frequency facilitation before and during application of the PKA inhibitor KT5720 for mossy fibers and assoc/com fEPSPs (n = 5).

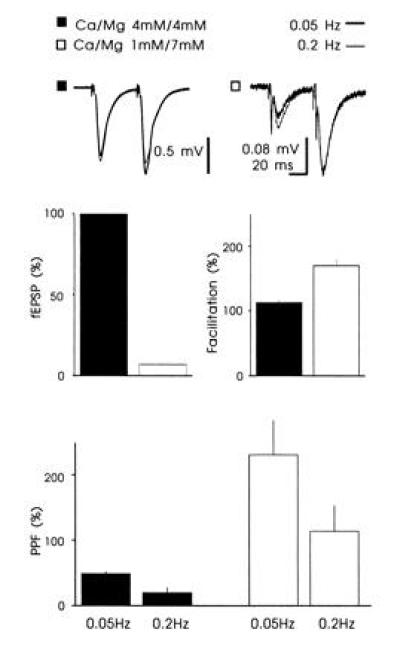

Why is frequency facilitation so much greater at the mossy fiber synapses compared with the assoc/com synapses? One possibility is that the baseline probability of transmitter release is much lower at mossy fiber synapses and therefore they can show greater increases in transmitter release during repetitive stimulation. If this were the case lowering the probability of release at assoc/com synapses should permit these synapses to facilitate to the same degree as mossy fiber synapses. We therefore decreased the probability of release by decreasing the Ca2+/Mg2+ ratio from 4 mM/4 mM to 1 mM/7 mM. Since it was difficult to record reliable assoc/com fields in the CA3 region during low levels of release, we examined excitatory synapses in the CA1 region, whose properties are virtually identical to those found at assoc/com synapses. Decreasing the Ca2+/Mg2+ ratio, greatly reduced the EPSP and resulted in a PPF that, on average (230%), was similar to that observed at mossy fiber synapses. However, despite the marked reduction in release probability, the frequency facilitation was only 55%, ≈50% of that seen at mossy fibers (n = 6) (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

The effect of decreasing the Ca2+/Mg2+ ratio on frequency facilitation at Schaffer collateral/com synapses. Decreasing the Ca2+/Mg2+ ratio reduced the slope of the fEPSP by 93 ± 0.6%, increased the PPF to 231 ± 53%, and increased the frequency facilitation by 55 ± 14% (n = 6). Voltage traces: Superimposed fEPSPs collected at two different frequencies. The experiments were performed in the presence of d-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (50 μM).

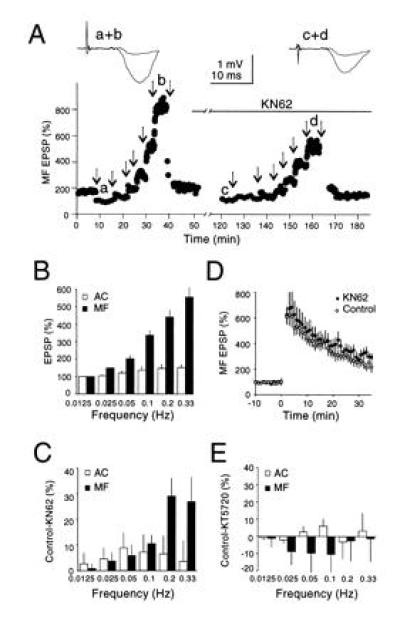

Although frequency facilitation and mossy fiber LTP appear to use different biochemical signaling pathways, both (6) are thought to be due to an increase in transmitter release. We therefore examined for possible interactions between these two forms of plasticity. As can be seen in the example (Fig. 6A) and summary graph (Fig. 6B, n = 6), the magnitude of the facilitation was markedly reduced after the induction of LTP. In addition the degree of interaction of frequency facilitation with LTP was correlated with the magnitude of LTP (Fig. 6C). However a complete occlusion of frequency facilitation was never observed, in agreement with the idea that mossy fiber LTP involves a change of both P (see ref. 6) and n (see ref. 13), while frequency facilitation involves primarily a change in P.

Figure 6.

Mossy fiber LTP reduces the dynamic range of frequency facilitation. (A) Amplitude of mossy fiber fEPSPs evoked at various stimulation frequencies before and after induction of LTP. Arrows indicate changes in stimulation frequencies (successively 0.0125 Hz, 0.025 Hz, 0.05 Hz, 0.1 Hz, 0.2 Hz, and 0.33 Hz). After LTP the stimulus strength was decreased to avoid possible nonlinearities during frequency facilitation. The voltage traces represent averaged fEPSPs collected at 0.0125 Hz and 0.33 Hz before and after induction of LTP. (B) Summary graph of the range of frequency facilitation before and after induction of LTP normalized to 0.0125 Hz (n = 6). The facilitation is significantly reduced at frequencies of stimulation higher than 0.1 Hz. (P < 0.001, two-tailed paired Student’s t test). (C) Correlation between amplitude of LTP and decrease in facilitation for the six experiments shown in B. The amplitude of the LTP was computed over a time window of 5 min, 30 min after induction. The decrease in facilitation was computed for 0.2 Hz stimulation.

DISCUSSION

Chemical synapses show a wide range of use dependent plasticity. Here we show that PPF and frequency facilitation, two forms of short term synaptic plasticity, differ dramatically at assoc/com and mossy fibers, which synapse onto the same CA3 pyramidal cells. While the duration of PPF for the two types of synapses (≈0.5 s) was similar, the magnitude of PPF was approximately twice as large at mossy fiber synapses. Assoc/com synapses were relatively insensitive to the frequency of stimulation, requiring frequencies greater than 0.1 Hz for enhancement to occur. The facilitation reached ≈25% at a frequency of 0.3 Hz. In contrast mossy fiber synapses were facilitated at frequencies above 0.0125 Hz and this reached a magnitude of 6-fold at a frequency of 0.3 Hz. Although frequency facilitation occurred at interstimulus intervals at least 10 times the effective intervals for PPF and decay differed by two orders of magnitude, these two forms of plasticity do interact. Thus the size of PPF decreased during frequency facilitation. If PPF is a measure of release probability, then mossy fibers have to be stimulated at 0.2 Hz to release with the same probability as assoc/com fibers at 0.05 Hz. At 1 Hz PPF was similar for both synapses.

Both PPF and frequency facilitation were greatly reduced in the presence of the membrane-permeant Ca2+ chelator EGTA-AM, indicating that these forms of plasticity are dependent on a rise in intraterminal Ca2+ (10). Considerable work has been done at other synapses on the role of Ca2+ in short-term plasticity. Although the effect of Ca2+ chelators on facilitation varies (14–16), all of these investigators agree that Ca2+ mediates the changes. It has been argued that residual free Ca2+ cannot account for the observed kinetics and that Ca2+ engages some high-affinity intermediary step. Indeed, in the experiments of Regehr et al. (10) the decay of the EPSP amplitude could be correlated to the decay of [Ca2+]i if a first- order reaction kinetic was taken into account. Our observations support such an indirect mechanism, since the CaM kinase II inhibitor KN62 inhibited the facilitation. In strains of Drosophila that express inhibitors of CaM kinase, facilitation at the neuromuscular junction is severely impaired (17), a finding which agrees with the present results. Our results do not allow us to determine the site of action of CaM kinase II—i.e., if it facilitates release by increasing p or by reducing vesicle depletion at higher frequencies.

The proposal that CaM kinase II mediates frequency facilitation is of particular interest in light of previous results suggesting that a Ca2+ activated adenylyl cyclase is required for mossy fiber LTP (11). Thus, activity dependent rises in intraterminal Ca2+ can activate two Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent enzymes: CaM kinase II activation resulting in a reversible enhancement and adenylyl cyclase in a persistent enhancement. Since LTP requires higher frequency stimulation it appears that in comparison to frequency facilitation, a higher level of Ca2+ is required for LTP. This differential activation presumably results from different sensitivities of the enzyme to Ca2+ or to different localization relative to presynaptic Ca2+ channels. The observation that frequency facilitation and mossy fiber LTP interact, suggests that, while they utilize distinct kinase pathways, they also share mechanisms. Interestingly, rabphillin that binds to the Rab vesicle proteins, has been shown to have phosphorylation sites both for protein kinase A and for CaM kinase II (18).

Why is frequency facilitation so different at assoc/com and mossy fiber synapses? A striking anatomical differences between these two synapse is that mossy fiber boutons have a large number of closely associated active zones (19, 20). During repetitive stimulation Ca2+ from one active zone could spread to neighboring active zones and enhance the probability of release. Such a mechanism has been proposed for the crayfish neuromuscular junction (21). Another possibility is that, the lower baseline probability of release at mossy fiber synapses, inferred from the larger PPF, gives a much greater range for increasing release at mossy fiber synapses. However, the frequency facilitation at nonmossy fiber synapses could not be converted to that seen at mossy fiber synapses by decreasing the probability of release. A third possibility is that endogenous Ca2+ buffers may be present at much higher concentrations in the assoc/com synapses. Thus in the presence of EGTA mossy fiber synapses behave very similar to assoc/com synapses. A final possibility is that some subset of the proteins involved in transmitter release differ at the two synapses.

To our knowledge, the mossy fiber synapse is the first in the mammalian central nervous system where synaptic integration over such a broad range of frequencies has been observed. This result is particularly interesting when correlated with the recent observation that granule cells typically fire at extremely low rates (22). In general synaptic integration occurs on the time scale of the membrane time constant of the postsynaptic neuron or via short-term presynaptic mechanisms such as PPF. For this kind of integration to occur, the presynaptic neuron must fire at corresponding frequencies, which are not commonly observed in granule cells. Thus the frequency facilitation of mossy fiber transmission allows processing of temporal information in the relevant range for granule cell activity—i.e., seconds to tens of seconds. Frequency dependent facilitation in this low frequency range will thus increase the signal-to-noise ratio of mossy fiber transmission and influence CA3 network activity according to both spatial and temporal patterns of granule cell activity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. M. Frerking and K. Vogt for their comments on the paper, and Helen Czerwonka for secretarial assistance. M.S. is supported by the CIBA–Geigy-Jubilaeums-Stiftung. R.A.N. is a member of the Keck Center for Integrative Neuroscience and the Silvio Conte Center for Neuroscience Research. R.C.M. is a member of the Center for Neurobiology and Psychiatry. R.A.N. and R.C.M. are supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: PPF, paired pulse facilitation; assoc/com, associational/commissural; CaM kinase II, calmodulin-dependent kinase II; NMDA, N-methyl-d-aspartate; BAPTA, bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetate; NBQX, 2,3-dihydroxy-6-nitro-7-sulfamoyl[f]quinoxaline; AMPA, α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid; CNQX, 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione; EPSP, excitatory postsynaptic potential; fEPSP, field EPSP; EPSC, excitatory postsynaptic current; LTP, long-term potentiation.

References

- 1.Castro-Alamancos M A, Connors B W. Science. 1996;272:274–277. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5259.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dempsey E W, Morison R S. Am J Physiol. 1943;138:283–296. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bliss T V P, Collingridge G L. Nature (London) 1993;361:31–39. doi: 10.1038/361031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicoll R A, Malenka R C. Nature (London) 1995;377:115–118. doi: 10.1038/377115a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buonomano D V, Merzenich M M. Science. 1995;267:1028–1030. doi: 10.1126/science.7863330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weisskopf M G, Nicoll R A. Nature (London) 1995;376:256–259. doi: 10.1038/376256a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamamoto C, Sawada S, Takada S. Exp Brain Res. 1983;51:128–134. doi: 10.1007/BF00236810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lanthorn T H, Ganong A H, Cotman C W. Brain Res. 1984;290:174–178. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90750-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zucker R S. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1989;12:13–31. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.12.030189.000305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Regehr W G, Delaney K R, Tank D W. J Neurosci. 1994;14:523–537. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-02-00523.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weisskopf M G, Castillo P E, Zalutsky R A, Nicoll R A. Science. 1994;265:1878–1882. doi: 10.1126/science.7916482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang Y-Y, Li X-C, Kandel E. Cell. 1994;79:69–79. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90401-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tong G, Malenka R C, Nicoll R A. Neuron. 1996;16:1147–1157. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80141-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hochner B, Parnas H, Parnas I. Neurosci Lett. 1991;125:215–218. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90032-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adler E M, Augustine G J, Duffy S N, Charlton M P. J Neurosci. 1991;11:1496–1507. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-06-01496.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanabe N, Kijima H. Neurosci Lett. 1988;92:52–57. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(88)90741-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang J, Renger J J, Griffith L C, Greenspan R J, Wu C F. Neuron. 1994;13:1373–1384. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90422-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fykse E M, Li C, Südhof T C. J Neurosci. 1995;15:2385–2395. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-03-02385.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamlyn L H. J Anat. 1962;96:112–126. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chicurel M E, Harris K M. J Comp Neurol. 1992;323:1–14. doi: 10.1002/cne.903250204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooper R L, Winslow J L, Govind C K, Atwood H L. J Neurophysiol. 1996;75:2451–2466. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.6.2451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jung M W, McNaughton B L. Hippocampus. 1993;3:165–182. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450030209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Treves A, Rolls E T. Hippocampus. 1994;4:374–391. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450040319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McNaughton B L, Nadel L. In: Neuroscience and Correctionist Theory. Gluck M A, Rumelhert D S, editors. Erlbaum; 1990. pp. 1–60. [Google Scholar]