Abstract

Diurnal patterns of circulating leptin concentrations are attenuated after consumption of fructose-sweetened beverages compared with glucose-sweetened beverages, likely a result of limited postprandial glucose and insulin excursions after fructose. Differences in postprandial exposure of adipose tissue to peripheral circulating fructose and glucose or in adipocyte metabolism of the two sugars may also be involved. Thus, we compared plasma leptin concentrations after 6-h iv infusions of saline, glucose, or fructose (15 mg/kg·min) in overnight-fasted adult rhesus monkeys (n = 9). Despite increases of plasma fructose from undetectable levels to about 2 mm during fructose infusion, plasma leptin concentrations did not increase, and the change of insulin was only about 10% of that seen during glucose infusion. During glucose infusion, plasma leptin was significantly increased above baseline concentrations by 240 min and increased steadily until the final 480-min time point (change in leptin = +2.5 ± 0.9 ng/ml, P < 0.001 vs. saline; percent change in leptin = +55 ± 16%; P < 0.005 vs. saline). Substantial anaerobic metabolism of fructose was suggested by a large increase of steady-state plasma lactate (change in lactate = 1.64 ± 0.15 mm from baseline), which was significantly greater than that during glucose (+0.53 ± 0.14 mm) or saline (−0.51 ± 0.14 mm) infusions (P < 0.001). Therefore, increased adipose exposure to fructose and an active whole-body anaerobic fructose metabolism are not sufficient to increase circulating leptin levels in rhesus monkeys. Thus, additional factors (i.e. limited post-fructose insulin excursions and/or hexose-specific differences in adipocyte metabolism) are likely to underlie disparate effects of fructose and glucose to increase circulating leptin concentrations.

PATTERNS OF SUGAR consumption in the U.S. population have changed markedly in the last three decades, with increasing calories derived from added sweeteners. Based on U.S. national food disappearance data, yearly per capita caloric sweetener consumption is estimated to have risen 19% during the period 1970–2005 (U.S. Department of Agriculture-Economic Research Service http://www.ers.usda.gov/Data/FoodConsumption/FoodAvailQueriable.aspx). It is estimated that sugar (glucose, fructose, and sucrose) constitutes about 24% of daily energy intake in the adult U.S. population (1), with calorically sweetened beverages accounting for more than 10% of daily energy requirements (2). Sweetened beverages have been implicated by some as a factor contributing to the rising obesity prevalence in the United States (3,4). It has been proposed that it is the fructose component of sucrose (50% fructose) and high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS, 42–55% fructose) that contributes to the effects of overconsumption of sweetened beverages to promote weight gain, dysregulation of lipid metabolism, and insulin resistance/glucose intolerance (1,4,5). Nevertheless, whether increased intake of fructose from sucrose and HFCS is a major contributing factor to the recent obesity epidemic remains open to debate (6), and other trends such as total caloric intake (increased ∼20% over the last three decades) and relatively low physical activity levels are also highly likely to have contributed to the increased prevalence of obesity and its associated metabolic disorders.

Assessment of the health impacts of consuming fructose and other dietary sugars will benefit from a greater understanding of the physiological changes accompanying their metabolism. In particular, studies are warranted that help clarify the mechanisms by which fructose influences metabolism and endocrine systems regulating energy homeostasis. In the context of a meal, fructose ingestion, whether by itself of as part of sucrose or HFCS, can result in sustained elevations of postprandial triglyceride levels in humans (7,8,9,10). This is likely explained by substantial hepatic flux of dietary fructose through fructokinase to triose phosphates, thus bypassing regulation at phosphofructokinase to provide lipogenic substrate in the postprandial state. With respect to hormonal profiles, compared with subjects consuming glucose-sweetened beverages with meals, consuming fructose beverages with each meal over the course of a day resulted in attenuated postprandial blood insulin and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) levels, reduced postprandial and diurnal circulating leptin concentration, and blunted postmeal suppression of plasma ghrelin concentrations (9). The insulin and GIP results in this study were consistent with other human studies in which postprandial insulin and GIP responses were not evident after intraduodenal infusion or oral administration of fructose, unlike glucose infusion that produced large increases in these hormones (11,12). Therefore, existing data indicate that high intakes of dietary fructose have the potential to promote undesirable effects on lipids and can produce an endocrine profile associated with body weight gain.

The mechanisms that underlie reduced postprandial and diurnal leptin responses after consumption of fructose remain to be fully explained. However, at least two possibilities exist. First, it is known that insulin stimulates leptin expression and secretion from adipocytes (13,14,15,16). Increased oxidative glucose metabolism is a key contributor to this process (17,18,19), which appears to involve the glucose- and insulin-regulated transcription factor Sp1 (20). It is possible that adipocyte uptake and metabolism of fructose differs from glucose and hence does not trigger leptin production to an equivalent degree. Second, the reduced leptin excursions after fructose consumption might be explained by relatively limited adipose tissue exposure to fructose because, as reviewed by Gaby (21), peak plasma concentrations of peripheral fructose after oral fructose challenges in humans are quite low (to ∼0.3–0.5 mm). We have observed similarly low fructose excursions in individuals consuming a beverage sweetened with 45 g fructose with mixed meals (Teff, K. L., S. H. Adams, and P. J. Havel, unpublished). This contrasts with circulating glucose concentrations, which peaked at about 2–5 mm above baseline fasting glucose concentrations when 45 g glucose was ingested with meals in the same subjects (9). Peripheral blood fructose levels after fructose consumption are attenuated by several factors: 1) when administered independently as single sugars, the rate of small intestinal uptake of fructose is significantly reduced compared with glucose (22,23,24,25); 2) relatively high metabolism of fructose to lactate occurs after fructose administration (9,26,27,28,29,30,31); and 3) the liver extracts a large fraction of fructose arriving via the portal circulation, estimated from portal-arterial concentration differences to be about 50–80% in rats (27,32,33,34), about 65–80% in baboons (35), and about 70–80% in humans (36,37).

Considering the uncertainties concerning the relative roles of postprandial circulating fructose levels or adipocyte fructose metabolism in the regulation of leptin production in vivo, in the present study, we measured plasma leptin responses to iv saline, fructose, or glucose administration in adult male rhesus monkeys. We hypothesized that fructose, unlike glucose, is a poor stimulus for leptin production even when its systemic availability is increased through iv infusion of the sugar.

Materials and Methods

Animals

The studies were conducted at the California National Primate Research Center (CNPRC) on the University of California, Davis, campus. The experimental protocol was performed in accordance with the guidelines of the U.S. Animal Welfare Act and after approval by the CNPRC Research Advisory Committee and the University of California, Davis, Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee. The CNPRC is an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care accredited facility. Nine adult (age 11–14 yr) male rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) weighing 8.6–15.9 kg (mean ± sem = 11.7 ± 0.8 kg) were used for these studies. Before selection for the study, a physical examination, complete blood count, and serum biochemistry panel was performed on each animal to exclude animals with signs of disease. The animals had previously been acclimated to several hours of chair restraint with a minimum of 10 training sessions (38), allowing for the studies to be conducted in conscious, unstressed animals.

Infusion protocol

Each animal was studied three times in a randomized order: 1) during saline infusion, 2) during glucose infusion, and 3) during fructose infusion. The studies were performed at least 7 d apart. The animals were fasted overnight and placed in restraint chairs at least 1 h before each experiment. Both right and left arm veins were catheterized, one for the infusion of sterile saline, glucose (sterile 50% dextrose solution in deionized water), or fructose (sterile 50% fructose solution in deionized water) and the other for blood sampling. Two baseline blood samples (3 ml each) were drawn from one catheter at −10 and 0 min and placed into tubes containing EDTA. Saline or glucose and fructose were infused into the contralateral catheter at a rate of 15 mg/kg·min. Blood samples were collected at 5, 15, 30, 60, 90, 120, 180, 240, 300, and 360 min during the infusions. At this time, the infusions were discontinued, the catheters were removed, and the animals were returned to their home cages. A final blood sample was taken 2 h later (at t = 480 min) from an arm vein while the animals remained in their cages. Samples were placed on ice until centrifuged to obtain plasma, which was frozen at −80 C until analyses for metabolites and hormones as described below.

Hormone and metabolite assays

Glucose and lactate were determined using a YSI Model 2300 Glucose-Lactate Analyzer (Yellow Springs, OH). Plasma triglycerides were assayed using a glycerol-3-phosphate-oxidase-based colorimetric kit per manufacturer’s instructions (Infinity triglycerides kit TR22421; Thermo, Waltham, MA) and using a Wallac Victor 2 plate reader (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). Plasma insulin concentrations were measured with a human insulin RIA kit (HI-14K; Linco Research, St. Louis, MO), and leptin concentrations were assayed using a primate leptin RIA kit (PL-84K; Linco).

Plasma fructose assay

Plasma fructose concentrations were determined using a modification of a commercial glucose/fructose analytical kit (Megazyme, catalog item K-FRUGL; Xygen Diagnostics Inc., Burgessville, Ontario, Canada) that contains the following: bottle 1 (2 m imidazole buffer plus magnesium chloride and sodium azide, pH 7.6), bottle 2 [β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (β-NADP+) and ATP], bottle 3 [425 U/ml hexokinase and 212 U/ml glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH)], and bottle 4 [1000 U/ml phosphoglucose isomerase (PGI)]. For each analysis, fresh assay buffer was made by mixing dionized water, bottle 1 contents, and bottle 2 contents (20:1:1). In each sample well of a 96-well plate (BD Falcon UV-Transparent Microplate, item 353261), 220 μl assay buffer and 10 μl sample were added and mixed using the plate shaker feature of a SpectraMax 340 PC Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) before adding 2 μl bottle 3 contents per well after which plates were mixed again. Incubations were conducted at 30 C for 50 min in the warmed chamber of the plate reader, and reduced NADP (NADPH) absorbance was measured at 340 nm as a measure of sample glucose concentration (NADPH generation from glucose-6-phosphate reaction with G6PDH). After this reading, 2 μl PGI per well was added and plates mixed and returned to 30 C. At 30 min, NADPH absorbance was measured (PGI converts fructose-6-phosphate to glucose-6-phosphate, with NADPH generation via G6PDH). The change in absorbance from the previous reading was used to determine fructose concentration from a standard curve. To account for matrix effects, fructose standards were diluted in an EDTA-plasma matrix (plasma from overnight-fasted human subjects containing no detectable fructose).

Statistics

A repeated-measures ANOVA was used to test for significant differences in outcome variables when comparing saline, glucose, and fructose treatments. Post hoc Bonferroni tests were performed when significant treatment or time × treatment interactions were observed (P < 0.05), comparing parameters during glucose or fructose infusion with saline controls and with one another.

Results

Plasma sugar and metabolite concentrations

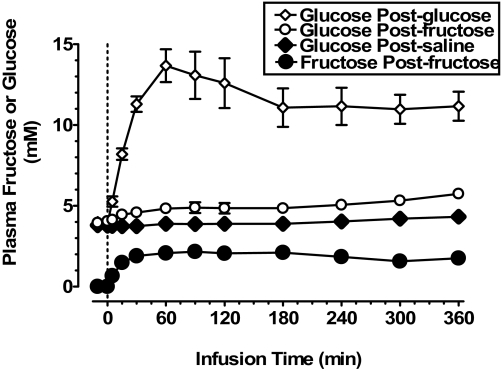

Fructose was not detectable in plasma samples from monkeys in the fasted state (Fig. 1) or in a subset of the samples collected from monkeys during glucose infusion (data not shown). Fructose concentrations plateaued between 30 and 60 min during iv fructose infusion, whereas during glucose infusion, plasma glucose peaked during this period and plateaued somewhat later. Consistent with observations after enteral or iv fructose administration in human subjects (9,26,28,29,31,36,37,39,40,41,42), there was a small but significant increase of plasma glucose concentrations during fructose infusion in monkeys (Fig. 1). The magnitude of increase of glucose concentrations during glucose infusion was markedly (>5-fold) larger compared with the increase of fructose concentrations during fructose infusion (∼11 mm and ∼2 mm at plateau, respectively) (P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Plasma concentrations of fructose and glucose in conscious adult male rhesus monkeys receiving iv infusions of saline, glucose, or fructose solutions over 360 min. All animals (n = 9) underwent the three treatments on different days in randomized order after a washout period between treatments (see Materials and Methods). Compared with saline treatment, fructose (15 mg/kg·min) elicited a modest increase in glucose levels (90, 240, and 300 min, P < 0.05; 360 min, P < 0.0001), whereas, as expected, during glucose infusion (15 mg/kg·min), there was marked increase of plasma glucose. Fructose was not detectable in plasma from fasted monkeys or during saline or glucose infusion.

Compared with glucose, enteral or iv fructose has been reported to substantially increase circulating lactate concentrations in humans (9,26,28,29,30,31,39,40,41,43). In monkeys, there was a significant effect of time (P < 0.0001), treatment (P < 0.001), and a time × treatment interaction (P < 0.0001) for the change of plasma lactate concentrations after infusion, with fructose infusion resulting in a large and sustained increase relative to saline infusion and greater than that observed during glucose infusion (Fig. 2A). Plasma levels of lactate in fructose-infused monkeys plateaued by 60 min. Plasma lactate concentrations were also significantly increased during the infusion of glucose compared with saline infusion (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Changes of plasma lactate and plasma triglyceride concentrations during 360-min iv infusions of saline, glucose, or fructose in adult male rhesus monkeys. A, Plasma lactate concentrations were significantly increased after glucose and fructose infusions compared with saline infusion (*, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001) and were consistently higher after fructose compared with glucose (180 and 300 min, P < 0.05; 360 min, P < 0.01). Baseline lactate concentrations (calculated as the average of values from −10 and 0 min) were 1.98 ± 0.50 mm, 1.48 ± 0.19 mm (glucose), and 1.89 ± 0.33 mm (fructose). B, Plasma triglyceride concentrations decreased significantly during glucose infusion to levels below those observed with saline (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). Differences in triglyceride levels comparing fructose to saline were not statistically significant; however, levels during fructose infusion remained significantly higher compared with during glucose infusion at 90 min and beyond (90 and 360 min, P < 0.01; 120–300 min, P < 0.001). Baseline fasting triglyceride concentrations were 54 ± 3 mg/dl (saline), 53 ± 3 mg/dl (glucose), and 50 ± 3 mg/dl (fructose).

After fructose-containing meals, increased plasma triglyceride concentrations are typically observed in human subjects (7,8,9). In the current studies in monkeys, there was a significant effect of time (P < 0.0001), treatment (P < 0.001), and a time × treatment interaction (P < 0.0001) for the changes of plasma triglycerides. Interestingly, we did not detect a significant increase of plasma triglyceride concentrations during fructose compared with saline infusion; however, during glucose infusion, plasma triglycerides were significantly decreased compared with saline or fructose infusion (Fig. 2B).

Plasma insulin and leptin concentrations

Insulin is an important stimulator of leptin production and secretion, in large part due to its ability to increase glucose uptake and metabolism in adipocytes (17,18,19) and through Sp1-mediated transcription of the leptin gene (20). As expected, during glucose infusion, there was a marked and sustained increase of plasma insulin concentrations compared with that observed during saline infusion, whereas during fructose infusion, there was a much smaller change of plasma insulin than during glucose infusion (Fig. 3A). There were significant effects of time (P < 0.0001), treatment (P = 0.02), and a time × treatment interaction (P < 0.0001) for changes of plasma insulin during the infusions.

Figure 3.

Changes of plasma insulin and leptin concentrations during 360-min iv infusions of saline, glucose, or fructose and in the 480-min postinfusion sample in adult male rhesus monkeys. A, Plasma insulin concentrations increased significantly during glucose infusion compared with saline treatment (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001) and returned to baseline levels after the termination of infusion. Differences in insulin levels during fructose infusion compared with saline infusion were not statistically significant, and levels were significantly below those measured during glucose administration (60 and 180 min, P < 0.05; 90 min, P < 0.001; 120 min, P < 0.01). Baseline fasting insulin concentrations were 37.3 ± 17.1 μU/ml (saline), 25.6 ± 6.5 μU/ml (glucose), and 26.5 ± 5.2 μU/ml (fructose). B, Relative to saline infusion, plasma leptin concentrations were increased progressively during glucose infusion by 240 min infusion and remained elevated at least 2 h after the infusions (*, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001 vs. saline). Plasma leptin was not significantly increased during fructose infusion relative to saline treatment, and levels remained lower than those measured during glucose infusion (240 and 300 min, P < 0.05; 360 and 480 min, P < 0.001). Baseline fasting leptin concentrations were 4.4 ± 2.0 ng/ml (saline), 4.9 ± 2.2 ng/ml (glucose), and 4.7 ± 2.4 ng/ml (fructose).

The attenuation of postprandial and diurnal circulating leptin patterns after fructose consumption in humans (9) could be a result of limited access of fructose to adipose tissue, due to active hepatic uptake from the portal circulation and/or rapid conversion of the sugar to other metabolites such as lactate, which would result in substantially diminished peripheral fructose concentrations. To our knowledge, however, this theory had not been directly investigated, prompting the determination of leptin concentrations in the peripheral circulation during iv infusion of fructose in monkeys. Plasma leptin concentrations were not significantly different at any time point during fructose compared with saline infusion (Fig. 3B), indicating that direct exposure of white adipose tissue to significant elevations of plasma fructose at a concentration of about 2 mm was not sufficient to increase leptin secretion. In contrast, during glucose infusion, there was a progressive increase of plasma leptin concentrations relative to those measured during saline infusion that was statistically significant after 240 min and became more pronounced thereafter (P < 0.001). There were significant effects of time (P = 0.02), treatment (P < 0.01), and a time × treatment interaction (P < 0.0001) for the changes of plasma leptin during the infusions.

Discussion

Differential effects on insulin, leptin, and gastrointestinal hormone secretion as well as on circulating lactate and lipids and macronutrient oxidation have been reported in studies comparing glucose and fructose ingestion in humans (7,8,9,10,11,12,26,28,31,44). For instance, the lipogenic actions of ingested fructose results in substantially increased postprandial triglycerides (9,10) as well as potential effects to induce liver triglyceride deposition and hepatic insulin resistance (5). Of particular note are the smaller postprandial (beginning 3–4 h after meals) and 24-h diurnal leptin concentrations when fructose- compared with glucose-sweetened beverages were consumed with mixed nutrient meals (9). A reduced capacity for ingested fructose to increase circulating leptin to the same degree as dietary glucose could result from 1) comparatively lower postprandial systemic exposure of adipose tissue to this hexose due to its more limited gut absorption compared with glucose (22,23,24,25) and/or its robust uptake by the liver and rapid conversion to lactate and other metabolites or 2) decreased adipocyte uptake and metabolism of fructose leading to reduced leptin secretion. To address these questions, we examined whether experimentally elevated fructose concentrations in the peripheral circulation achieved through iv fructose infusion would increase plasma leptin concentrations in rhesus monkeys. Fructose infusion resulted in a steady-state plasma fructose concentration (∼2 mm) at least 4-fold higher than typical peak postprandial levels determined after consumption of substantial quantities of fructose in humans (21,26,28,48) (Teff, K. L., S. H. Adams, and P. J. Havel, unpublished). Plasma leptin concentrations did not increase in the animals in response to fructose infusion, indicating that this degree of elevation in plasma fructose concentration is not alone sufficient to stimulate leptin production by adipose tissue in vivo.

In contrast to fructose, during glucose infusion in monkeys, there was a progressive increase of plasma leptin concentrations beginning at 4 h into the infusion consistent with the known time course for insulin and glucose administration to increase circulating leptin concentration in human subjects (9,18,49,50). Glucose infusion was accompanied by markedly increased plasma insulin concentrations, and insulin is known to increase leptin expression and secretion from adipocytes (13,14,15,16) through a mechanism that involves increased oxidative glucose metabolism (17), whereas anaerobic metabolism of glucose does not increase leptin production (18,19,51). In contrast, fructose is a poor insulin secretagogue (52,53,54). Consistent with the weak effect of fructose to trigger insulin secretion, steady-state plasma insulin concentrations during fructose infusion in monkeys were only marginally increased compared with baseline levels or saline-infused animals in which plasma insulin levels were modestly decreased during the infusion period. Limited insulin responses to fructose administration are also observed in humans, most likely as a result of small increases in blood glucose concentrations that occur from conversion of ingested fructose to glucose (7,9,12,28,29,31,44,48). One consequence of these differences in insulin responses was a significant decrease of plasma triglycerides during glucose, but not during fructose or saline, infusions. In the fasted state, circulating triglycerides are derived largely from liver reesterification of lipolysis-derived free fatty acids. Triglyceride concentrations likely decreased during glucose infusion because the large increases of insulin activate lipoprotein lipase, suppress lipolysis, and increase free fatty acid reesterification in adipose tissue. Similarly, the increased anaerobic metabolism indicated by markedly elevated lactate concentration during fructose compared with glucose infusion is likely to be, at least in part, due to decreased insulin-mediated flux of pyruvate derived from fructose metabolism into mitochondrial oxidation though pyruvate dehydrogenase, an enzyme complex that is activated by insulin. Based on limited data from studies in rat adipocytes in vitro, there is evidence that insulin can stimulate fructose uptake and metabolism in fat cells (55,56,57), albeit to a much lesser degree than glucose (57). Thus, it is possible that the limited insulin response during fructose infusion observed in vivo results in decreased adipocyte utilization of fructose, masking any potential effects of the available fructose in the peripheral circulation. This possibility can be tested in experiments measuring leptin responses during simultaneous administration of fructose with and without exogenous insulin administration.

Other factors that could contribute to differences in the postprandial leptin response between glucose and fructose in vivo include insulin-independent differences in utilization of the two sugars by adipocytes and hexose accessibility to the adipose tissue. Adipocytes are known to metabolize fructose through mechanisms that rely on uptake through glucose transporter 5 (GLUT5) (55,56,57) and possibly other hexose transporters that are present in adipocytes (58). Froesch and Ginsberg (55) determined that fructose uptake, utilization for glycerol synthesis, and oxidative metabolism to CO2 were relatively high in rat adipocytes (>50–80% that of glucose), and there is substantial metabolism of fructose to lipids in rat adipocytes (59). Litherland et al. (57) reported fructose uptake and conversion to lactate and triglyceride in isolated rat adipocytes at concentrations of 100 μm. Thus, the plasma fructose levels observed in the current study would appear to be well above those required for active metabolism of the fructose by adipose tissue. It is possible, however, that leptin secretion would be stimulated at higher plasma concentrations of fructose, because uptake and metabolism of fructose by rat adipocytes increases in a concentration-dependent manner (55,59), and leptin secretion from rat adipocytes is increased during prolonged exposure to 5 mm fructose (17). Nevertheless, leptin secretion at higher fructose concentrations would not have direct relevance to the normal postprandial physiological state, because the plasma fructose concentrations of about 2 mm achieved during fructose infusion in the present study were well above those measured (∼0.3–0.5 mm) after intake of substantive amounts of fructose in humans (21,26,28,48) (Teff, K. L., S. H. Adams, and P. J. Havel, unpublished).

One limitation of the current study to these interpretations regarding leptin regulation is that steady-state plasma fructose concentrations during fructose infusion were significantly lower compared with glucose concentrations during the same rate of glucose infusion. The reason that fructose levels were lower likely reflects avid uptake of fructose by the liver and its conversion to other metabolites, particularly its anaerobic metabolism to lactate. A fraction of infused fructose was likely converted to glucose in the liver, as suggested by the small but significant and progressive increase of plasma glucose measured in the animals during infusion of fructose. Small increases of glucose have also been observed after fructose administration in humans (9,26,28,29,31,36,37,39,40,41,42), and hepatic gluconeogenesis is stimulated by fructose in a dose-dependent fashion in rats (60) and in humans (45). It is also possible that some fructose spilled over into the urine during the infusions; however, the potential impact of this on steady-state plasma levels would be expected to be negligible considering that in humans, at most, about 1% of fructose is recovered in the urine after enteral or iv administration (39,46,47). Despite the limitations noted with respect to steady-state differences in fructose and glucose concentrations during glucose and fructose infusion, the present data clearly indicate that experimental elevations of peripheral fructose concentrations that are sufficient to result in active tissue uptake and metabolism to lactate are not sufficient to increase leptin production in vivo.

Summary

Marked increases of circulating lactate, a limited insulin response, and relatively low leptin excursions have been reported after fructose consumption in human studies. The same pattern was observed in the present study during the iv infusion of fructose when compared with glucose infusion in rhesus monkeys. Directly increasing plasma fructose concentrations to about 2 mm by iv infusion of fructose did not increase circulating leptin concentrations, indicating that increased exposure of adipose tissue to fructose per se cannot alone stimulate leptin secretion by adipose tissue in vivo. Therefore, previous reports of relatively attenuated postprandial 24-h diurnal circulating leptin responses to dietary fructose in humans (9) may involve a limited effect of fructose to stimulate insulin secretion and/or a comparatively large whole-body and adipocyte anaerobic conversion of fructose to lactate.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the expert technical assistance of Phil Allen, Vanessa Bakula, and James Graham. We thank Jenny Short and Sarah Davis for their help in coordinating the studies and Dr. Andrew G. Hendrick and the Venture Research Program of the California National Primate Research Center (RR-00169) for supporting this project.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK-50129 and RR-00169 (to P.J.H.), and intramural USDA-ARS CRIS 5306-51530-016-00D (to S.H.A.). P.J.H. also receives support from National Institutes of Health Grants HL-075675, HL-091333, AT-002599, AT-002993, and AT-003645; the Clinical and Translational Science Center at the University of California, Davis (RR-25146); and the American Diabetes Association.

Disclosure Statement: The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

First Published Online February 28, 2008

Abbreviations: GIP, Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide; G6PDH, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; PGI, phosphoglucose isomerase; HFCS, high-fructose corn syrup; β-NADP, β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; NADPH, reduced NADP.

References

- Havel PJ 2005 Dietary fructose: implications for dysregulation of energy homeostasis and lipid/carbohydrate metabolism. Nutr Rev 63:133–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popkin BM, Armstrong LE, Bray GM, Caballero B, Frei B, Willett WC 2006 A new proposed guidance system for beverage consumption in the United States. Am J Clin Nutr 83:529–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray GA, Nielsen SJ, Popkin BM 2004 Consumption of high-fructose corn syrup in beverages may play a role in the epidemic of obesity. Am J Clin Nutr 79:537–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik VS, Schulze MB, Hu FB 2006 Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr 84:274–288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanhope KL, Havel PJ 2008 Fructose consumption: potential mechanisms for its effects to increase visceral adiposity and induce dyslipidemia and insulin resistance. Curr Opin Lipidol 19:16–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachman CM, Baranowski T, Nicklas TA 2006 Is there an association between sweetened beverages and adiposity? Nutr Rev 64:153–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraha A, Humphreys SM, Clark ML, Matthews DR, Frayn KN 1998 Acute effect of fructose on postprandial lipaemia in diabetic and non-diabetic subjects. Br J Nutr 80:169–175 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JC, Schall R 1988 Reassessing the effects of simple carbohydrates on the serum triglyceride responses to fat meals. Am J Clin Nutr 48:1031–1034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teff KL, Elliott SS, Tschop M, Kieffer TJ, Rader D, Heiman M, Townsend RR, Keim NL, D'Alessio D, Havel PJ 2004 Dietary fructose reduces circulating insulin and leptin, attenuates postprandial suppression of ghrelin, and increases triglycerides in women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:2963–2972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanhope KL, Griffen SC, Bair BR, Swarbrick MM, Keim NL, Havel PJ, Twenty-four hour endocrine and metabolic profiles following consumption of high fructose corn syrup-, sucrose-, fructose-, and glucose-sweetened beverages with meals. Am J Clin Nutr, in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganda OP, Soeldner JS, Gleason RE, Cleator IG, Reynolds C 1979 Metabolic effects of glucose, mannose, galactose, and fructose in man. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 49:616–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayner CK, Park HS, Wishart JM, Kong M, Doran SM, Horowitz M 2000 Effects of intraduodenal glucose and fructose on antropyloric motility and appetite in healthy humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 278:R360–R366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saladin R, De Vos P, Guerre-Millo M, Leturque A, Girard J, Staels B, Auwerx J 1995 Transient increase in obese gene expression after food intake or insulin administration. Nature 377:527–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leroy P, Dessolin S, Villageois P, Moon BC, Friedman JM, Ailhaud G, Dani C 1996 Expression of ob gene in adipose cells. Regulation by insulin. J Biol Chem 271:2365–2368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmstrom R, Taskinen MR, Karonen SL, Yki-Jarvinen H 1996 Insulin increases plasma leptin concentrations in normal subjects and patients with NIDDM. Diabetologia 39:993–996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng D, Jones JP, Usala SJ, Dohm GL 1996 Differential expression of ob mRNA in rat adipose tissues in response to insulin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 218:434–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller WM, Gregoire FM, Stanhope KL, Mobbs CV, Mizuno TM, Warden CH, Stern JS, Havel PJ 1998 Evidence that glucose metabolism regulates leptin secretion from cultured rat adipocytes. Endocrinology 139:551–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellhoener P, Fruehwald-Schultes B, Kern W, Dantz D, Kerner W, Born J, Fehm HL, Peters A 2000 Glucose metabolism rather than insulin is a main determinant of leptin secretion in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85:1267–1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Aliaga MJ, Stanhope KL, Havel PJ 2001 Transcriptional regulation of the leptin promoter by insulin-stimulated glucose metabolism in 3T3–L1 adipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 283:544–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Aliaga MJ, Swarbrick MM, Lorente-Cebrian S, Stanhope KL, Havel PJ, Martinez JA 2007 Sp1-mediated transcription is involved in the induction of leptin by insulin-stimulated glucose metabolism. J Mol Endocrinol 38:537–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaby AR 2005 Adverse effects of dietary fructose. Altern Med Rev 10:294–306 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravich WJ, Bayless TM, Thomas M 1983 Fructose: incomplete intestinal absorption in humans. Gastroenterology 84:26–29 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kneepkens CM, Vonk RJ, Fernandes J 1984 Incomplete intestinal absorption of fructose. Arch Dis Child 59:735–738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumessen JJ, Gudmand-Hoyer E 1986 Absorption capacity of fructose in healthy adults. Comparison with sucrose and its constituent monosaccharides. Gut 27:1161–1168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truswell AS, Seach JM, Thorburn AW 1988 Incomplete absorption of pure fructose in healthy subjects and the facilitating effect of glucose. Am J Clin Nutr 48:1424–1430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald I, Keyser A, Pacy D 1978 Some effects, in man, of varying the load of glucose, sucrose, fructose, or sorbitol on various metabolites in blood. Am J Clin Nutr 31:1305–1311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niewoehner CB, Gilboe DP, Nuttall GA, Nuttall FQ 1984 Metabolic effects of oral fructose in the liver of fasted rats. Am J Physiol 247:E505–E512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz JM, Schutz Y, Piolino V, Schneider H, Felber JP, Jequier E 1992 Thermogenesis in obese women: effect of fructose vs. glucose added to a meal. Am J Physiol 262:E394–E401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruszynska YT, Meyer-Alber A, Wollen N, McIntyre N 1993 Energy expenditure and substrate metabolism after oral fructose in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol 19:241–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruszynska YT, Harry DS, Fryer LG, McIntyre N 1994 Lipid metabolism and substrate oxidation during intravenous fructose administration in cirrhosis. Metabolism 43:1171–1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delarue J, Couet C, Cohen R, Brechot JF, Antoine JM, Lamisse F 1996 Effects of fish oil on metabolic responses to oral fructose and glucose loads in healthy humans. Am J Physiol 270:E353–E362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill R, Baker N, Chaikoff IL 1954 Altered metabolic patterns induced in the normal rat by feeding an adequate diet containing fructose as sole carbohydrate. J Biol Chem 209:705–716 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topping DL, Mayes PA 1971 The concentration of fructose, glucose and lactate in the splanchnic blood vessels of rats absorbing fructose. Nutr Metab 13:331–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y, Bizeau ME, Pagliassotti MJ 2004 An acute increase in fructose concentration increases hepatic glucose-6-phosphatase mRNA via mechanisms that are independent of glycogen synthase kinase-3 in rats. J Nutr 134:545–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossley JN, Macdonald I 1970 The influence in male baboons, of a high sucrose diet on the portal and arterial levels of glucose and fructose following a sucrose meal. Nutr Metab 12:171–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dencker H, Lunderquist A, Meeuwisse G, Norryd C, Tranberg KG 1972 Absorption of fructose as measured by portal catheterization. Scand J Gastroenterol 7:701–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dencker H, Meeuwisse G, Norryd C, Olin T, Tranberg KG 1973 Intestinal transport of carbohydrates as measured by portal catheterization in man. Digestion 9:514–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havel PJ, Valverde C 1996 Autonomic mediation of glucagon secretion during insulin-induced hypoglycemia in rhesus monkeys. Diabetes 45:960–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook GC 1969 Absorption products of D(−) fructose in man. Clin Sci 37:675–687 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook GC 1971 Absorption and metabolism of D(−) fructose in man. Am J Clin Nutr 24:1302–1307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook GC, Jacobson J 1971 Individual variation in fructose metabolism in man. Br J Nutr 26:187–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohannon NV, Karam JH, Forsham PH 1980 Endocrine responses to sugar ingestion in man. Advantages of fructose over sucrose and glucose. J Am Diet Assoc 76:555–560 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook GC 1970 Comparison of the absorption and metabolic products of sucrose and its monosaccharides in man. Clin Sci 38:687–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong MF, Chapman I, Goble E, Wishart J, Wittert G, Morris H, Horowitz M 1999 Effects of oral fructose and glucose on plasma GLP-1 and appetite in normal subjects. Peptides 20:545–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surmely JF, Paquot N, Schneiter P, Jequier E, Temler E, Tappy L 1999 Non oxidative fructose disposal is not inhibited by lipids in humans. Diabetes Metab 25:233–240 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranade VG, Abhyankar HN, Rathod RN 1975 Urinary fructose excretion in health after fructose test. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol 19:221–223 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasevska N, Runswick SA, McTaggart A, Bingham SA 2005 Urinary sucrose and fructose as biomarkers for sugar consumption. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 14:1287–1294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avgerinos A, Harry D, Bousboulas S, Theodossiadou E, Komesidou V, Pallikari A, Raptis S, McIntyre N 1992 The effect of an eucaloric high carbohydrate diet on circulating levels of glucose, fructose and non-esterified fatty acids in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol 14:78–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden G, Chen X, Mozzoli M, Ryan I 1996 Effect of fasting on serum leptin in normal human subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 81:3419–3423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saad MF, Khan A, Sharma A, Michael R, Riad-Gabriel MG, Boyadjian R, Jinagouda SD, Steil GM, Kamdar V 1998 Physiological insulinemia acutely modulates plasma leptin. Diabetes 47:544–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller WM, Stanhope KL, Gregoire F, Evans JL, Havel PJ 2000 Effects of metformin and vanadium on leptin secretion from cultured rat adipocytes. Obes Res 8:530–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz FC, Maney JW, Greenberg BZ 1967 The regulation of insulin secretion: effects of the infusion of glucose, ribose, and other sugars into the portal veins of dogs. J Lab Clin Med 69:537–557 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giroix MH, Scruel O, Ladriere L, Sener A, Portha B, Malaisse WJ 1999 Metabolic and secretory interactions between d-glucose and d-fructose in islets from GK rats. Endocrinology 140:5556–5565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scruel O, Giroix MH, Sener A, Portha B, Malaisse WJ 1999 Metabolic and secretory response to d-fructose in pancreatic islets from adult rats injected with streptozotocin during the neonatal period. Mol Genet Metab 68:86–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froesch ER, Ginsberg JL 1962 Fructose metabolism of adipose tissue. I. Comparison of fructose and glucose metabolism in epididymal adipose tissue of normal rats. J Biol Chem 237:3317–3324 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajduch E, Darakhshan F, Hundal HS 1998 Fructose uptake in rat adipocytes: GLUT5 expression and the effects of streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Diabetologia 41:821–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litherland GJ, Hajduch E, Gould GW, Hundal HS 2004 Fructose transport and metabolism in adipose tissue of Zucker rats: diminished GLUT5 activity during obesity and insulin resistance. Mol Cell Biochem 261:23–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manolescu AR, Witkowska K, Kinnaird A, Cessford T, Cheeseman C 2007 Facilitated hexose transporters: new perspectives on form and function. Physiology (Bethesda) 22:234–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrana A, Fabry P, Kazdova L 1972 Utilization of 14C-glucose and 14C-fructose in adipose tissue of rats fed a starch or sucrose diet. Rev Eur Etud Clin Biol 17:611–614 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youn JH, Youn MS, Bergman RN 1986 Synergism of glucose and fructose in net glycogen synthesis in perfused rat livers. J Biol Chem 261:15960–15969 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]