Abstract

The mechanisms underlying cellular injury when human placental trophoblasts are exposed to hypoxia are unclear. Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) mediates cell injury and fibrosis in diverse tissues. We hypothesized that hypoxia enhances the production of CTGF in primary term human trophoblasts. Using cultured term primary human trophoblasts as well as villous biopsies from term human placentas, we showed that CTGF protein is expressed in trophoblasts. When compared with cells cultured in standard conditions (FiO2 = 20%), exposure of primary human trophoblasts to low oxygen concentration (FiO2 = 8% or ≤ 1%) enhanced the expression of CTGF mRNA in a time-dependent manner, with a significant increase in CTGF levels after 16 h (2.7 ± 0.7-fold; P < 0.01), reaching a maximum of 10.9 ± 3.2-fold at 72 h. Whereas exposure to hypoxia had no effect on cellular CTGF protein levels, secretion of CTGF to the medium was increased after 16 h in hypoxia and remained elevated through 72 h. The increase in cellular CTGF transcript levels and CTGF protein secretion was recapitulated by exposure of trophoblasts to agents that enhance the activity of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)1α, including cobalt chloride or the proline hydroxylase inhibitor dimethyloxaloylglycine, and attenuated using the HIF1α inhibitor 2-methoxyestradiol. Although all TGFβ isoforms stimulated the expression of CTGF in trophoblasts, only the expression of TGFβ1 mRNA was enhanced by hypoxia. We conclude that hypoxia increases cellular CTGF mRNA levels and CTGF protein secretion from cultured trophoblasts, likely in a HIF1α-dependent manner.

INTACT PLACENTAL function is critical for normal growth and development of the mammalian embryo. The villus is the main functional unit within the human hemochorial placenta, and its surface trophoblast determines the transport of oxygen, nutrients, and waste products between fetal and maternal blood (reviewed in Refs. 1 and 2). The connective tissue of the villous core encases fetal vessels that permeate the villous tree. The trophoblast generates important endocrine and paracrine cues, which are implicated in the regulation of fetal growth and the maintenance of pregnancy. Injury to placental villous trophoblasts, attributed to hypoperfusion of the placental bed secondary to vascular insufficiency, is commonly associated with fetal growth restriction (FGR) (3,4). In its more severe form, this disease affects 3% of all pregnancies, and is associated with increased perinatal-neonatal mortality and morbidity, developmental delay, neurobehavioral dysfunction during childhood, and the metabolic syndrome during adult life (5,6). At the present time there is no treatment for FGR, except for optimization of the timing of delivery, intended to avert further injury.

Villous hypoxia is physiological in early fetoplacental development until late in the first trimester, when maternal blood begins to perfuse the intervillous space (7,8,9). Trophoblast hypoxia becomes abnormal after the first trimester, when partial pressure of oxygen in the placental bed increases from 15–20 to 50–60 mm Hg (7,10). Experiments using exposure of cultured trophoblasts to hypoxia, a common approach to study hypoxia-induced injury, suggest that the response of third trimester trophoblasts to hypoxia is different from that of first trimester trophoblasts. We and others have found that exposure of term primary human trophoblasts (PHTs) to hypoxic injury in vitro mitigates differentiation, and causes cell injury and apoptosis (11,12,13,14). Reduced placental size, villous surface area, and vascularity are frequent findings in pregnancies complicated by FGR attributed to placental injury (15). Additional histological lesions include evidence of ischemia and infarct, fetal thrombotic vasculopathy, previllous fibrin or chronic villitis, which are postulated to contribute to trophoblast hypoxic injury (16).

The molecular signals that regulate trophoblast response to injury are largely unknown. Using high-density oligonucleotide microarray screens, analyzed using correction to signal intensity and probe reliability (17), we previously showed a higher expression of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) in cultured human trophoblasts that were exposed to hypoxia in vitro compared with standard culture conditions, as well as in placental villous samples from pregnancies complicated by FGR vs. matched controls (18). CTGF is a heparin-binding 38-kDa member of the CTGF, Cyr61, and Nov (CCN) family of proteins that promote cell proliferation, cell migration, adhesion, angiogenesis, formation of extracellular matrix, fibrosis, and apoptosis, targeting primarily fibroblasts, endothelial cells, epithelial cells, chondrocytes, myocytes, mesangial cells, and neurons (reviewed in Refs. 19,20,21). During pregnancy CTGF (also known as CCN2 and Fisp12) is expressed in the uterine decidua, as well as in the trophectoderm and inner cell mass of the preimplantation murine embryo (22). Later in development CTGF is expressed in the murine placenta, primarily in giant cells (E 14.5) (23). Consistent with its high expression in embryonic vascular tissues and chondrocytes, CTGF deficient mice exhibit multiple defects in cartilage and matrix remodeling, chondrocyte proliferation, and angiogenesis within the bony growth plate, but no placental defects (24). Overexpression of CTGF, targeted to chondrocytes, led to postnatal dwarfism and reduced bone mass (25). Interestingly, another member of the CCN family, Cyr61 (CCN1, which has ∼50% homology to CTGF), plays a key role in murine placental development, with Cyr61 mutant mice exhibiting increased midgestational lethality, reflecting abnormal nonsprouting angiogenesis in the chorion and allantois. These lesions result in defective chorioallantoic fusion and fetal undervascularization of the placenta without a primary defect in the labyrinthine trophoblast or spongiotrophoblast (26). Because CTGF plays a central role in fibrosis and adaptation to injury in numerous organs, fibrin deposition and fibrosis are important lesions in injured villous trophoblasts in the human, and CTGF expression was up-regulated in our screen of hypoxic trophoblasts and FGR placentas, we hypothesized that hypoxia enhances the expression of CTGF in term human trophoblasts.

Materials and Methods

Trophoblast culture

The procurement of tissues for our studies was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Washington University School of Medicine. PHT cells were prepared from normal term placentas using the trypsin-deoxyribonuclease-dispase/Percoll method as described by Kliman et al., with previously published modifications (12,27). Cultures were plated at a density of 300,000 cells per cm2 and maintained in DMEM (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) containing 10% FBS (Sigma-Aldrich), 20 mmol/liter HEPES (pH 7.4) (Sigma-Aldrich), penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and Fungizone (0.25 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich), all from Washington University tissue culture support center, at 37 C in a 5% carbon dioxide-air atmosphere. After 4 h, designed to allow cell attachment, the cells were washed three times in PBS, and the culture medium was replaced by medium containing FBS or serum free medium. This time point is defined as time zero for our experiments. When incubated for more than 24 h, the culture medium was changed every 24 h. Cells were cultured in either standard (FiO2 = 20%) or hypoxic growth conditions (FiO2 ≤ 1 or 8%). Cultures at the two hypoxic conditions were maintained concomitantly in two side-by-side incubators (Thermo Electron, Marietta, OH) that provided a defined hypoxic atmosphere of either less than 1 or 8% O2, where stated (5% CO2 and complemented by N2, with added 10% H2 to the < 1% O2). The level of FiO2 was continuously monitored using two separate oxygen sensors (KE-50; Figaro USA, Inc., Glenview, IL), which allowed a simultaneous recording of atmospheric conditions in each chamber (<0.1% change in FiO2). Where indicated, the cultures were supplemented with dimethyloxaloylglycine (DMOG) (Cayman, Ann Arbor, MI), cobalt chloride (CoCl2) (Sigma-Aldrich), TGFβ1, 2, and 3 (Sigma-Aldrich), 2-methoxy estradiol (Sigma-Aldrich), monensin sodium (Sigma-Aldrich), or recombinant CTGF (full-length from Promokine, Heidelberg, Germany, or the 98 aa C-terminal domain from Cell Sciences, Canton, MA). The concentrations are listed in each figure legend.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence

Placental biopsies from term uncomplicated pregnancies were collected immediately after delivery, fixed for 24 h in 10% neutral buffered formalin, and embedded in paraffin. Five-micron sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in an ethanol gradient. Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched using 3% H2O2 in methanol for 30 min. After equilibrating for 5 min in distilled water, the samples were heated in a microwave at maximum power for 10 min. The slides were washed, blocked for 60 min with normal goat serum, and incubated for 2 h at room temperature in the absence or presence of affinity purified goat polyclonal anti-CTGF antibody (final 4 μg/ml; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA). The antibody was also preincubated for 2 h at room temperature with CTGF specific blocking peptide (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at a ratio of 5:1 blocking peptide to antibody. The mixture was then used for staining. After washes, the slides were incubated for 30 min with a biotinylated horse antigoat secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), followed by 30 min incubation with avidin/biotin-horseradish peroxidase complex (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and 3-min incubation with diaminobenzidine (Zymed Laboratories, Inc., San Francisco, CA). The slides were rinsed and counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich), dehydrated in ethanol, cleared with xylene, and mounted with glass coverslips using Histomount (Zymed Laboratories).

For immunofluorescence of CTGF, we cultured primary trophoblasts for 72 h and stained the cells for desmosomes using mouse antidesmosome antibody as we previously described (12). For fluorescent detection of CTGF, we incubated the cells with rabbit anti-CTGF antibody (final 2 μg/ml; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), diluted in blocking buffer for 1 h. After washes, the cells were incubated with a cocktail of Alexa Fluor 555-linked donkey antirabbit IgG (final 8 μg/ml, Alexa Fluor 555; Molecular Probes/Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA) and Alexa Fluor 488-linked donkey antimouse IgG (final 8 μg/ml; Molecular Probes) for an additional 30 min at room temperature. After washing, the cells were stained with 1:250 TO-PRO-3 iodide (Invitrogen) for 15 min, and then mounted with GelMount (Biomeda, Foster City, CA) and viewed using a Nikon E800 fluorescence confocal microscope (Nikon Corp., Tokyo, Japan). A syncytium was defined as three or more nuclei in the same cytoplasm without intervening surface desmosomal membrane staining.

Western immunoblotting and concentration of medium CTGF

Trophoblasts were lysed with cold lysis buffer (1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% deoxycholate, and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate in PBS) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). The plates were scraped, and the lysate was sonicated on ice, centrifuged, and protein concentration was determined. For detection of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) 1α, the extraction was performed in 2× sample buffer instead of the lysis buffer, and without sonication. The proteins (20–30 μg/lane) were resolved using either 10% (CTGF) or 6% (HIF1α) SDS-PAGE at 80 V for 3 h, and then transferred overnight to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Immobilon-P; Millipore, Bedford, MA) at 4 C, 150 mA. After blocking for 1 h in 5% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline (with 0.05% Tween 20), the blots were incubated with an affinity purified rabbit polyclonal anti-CTGF antibody (final 0.2 μg/ml; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse monoclonal anti-HIF1α (final 1.3 μg/ml, NB-100–105; Novus Biologicals, Inc., Littleton, CO), or goat polyclonal antiactin (final 0.2 μg/ml; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 2 h, followed by the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary IgG antibodies (all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 1 h at room temperature, and processed for luminescence using the Amersham Pharmacia ECL kit (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences Corp., Piscataway, NJ). Chemiluminescence was densitometrically analyzed using Epichemi-3 software (UVP BioImaging System; Ultraviolet Products, Upland, CA).

For detection of CTGF in the culture medium, we used a disposable ultrafiltration centrifugal device for medium concentration (iCON Concentrator, 7 ml/20 K; Pierce, Rockford, IL), which has a molecular weight cutoff of 20,000. Serum free medium samples (5 ml) were collected from trophoblasts and placed in the upper sample chamber of concentrator tube. The tube was centrifuged at 1600 × g for 20 min at 4 C using a swinging-bucket rotor. The concentrated sample (50–70 μl) was collected from the upper chamber and added to sample buffer after adjustment for protein concentration of the plated cells. CTGF was detected using immunoblotting as described previously.

Quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR)

RNA was purified from primary trophoblasts using TriReagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH) and processed for RT as we previously described (28). For RT-qPCR we used 2 μg cDNA and 300 nm of each forward and reverse gene-specific primer as specified in Table 1, with specificity confirmed using BLAST. The PCR mixture (25 μl), prepared as we previously described (28), was incubated at 50 C for 2 min and 95 C for 10 min. Each reaction was run in duplicate using an Applied Biosystems Geneamp 7300 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) at 95 C for 15 sec and 60 C for 1 min for 40 cycles. Expression of each transcript was normalized to the level of tyrosine 3-monooxygenase/tryptophan 5-monooxygenase activation protein, ζ polypeptide (YWHAZ) (29). Reactions and dissociation curves were analyzed as we previously described (28) using the 2−ΔΔCT method (30).

Table 1.

Forward and reverse gene-specific primers

| Name | Accession no. | Direction and site | Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTGF | X78947 | F(639–657) | TGTGTGACGAGCCCAAGGA |

| R(717–698) | TCTGGGCCAAACGTGTCTTC | ||

| TGFβ1 | NM_000660 | F(599–617) | CTCTCCGACCTGCCACAGA |

| R(670–651) | AACCTAGATGGGCGCGATCT | ||

| TGFβ2 | NM_003238 | F(231–249) | TCGCGCTCAGCCTGTCTAC |

| R(303–287) | CGGATCGCCTCGATCCT | ||

| TGFβ3 | NM_003238 | F(231–249) | GGAAAACACCGAGTCGGAATAC |

| R(303–287) | GCGGAAAACCTTGGAGGTAAT | ||

| VEGF | AF024710 | F(681–699) | CTGGCGCTGAGCCTCTCTA |

| R(754–735) | CCGGTGTCCTCATCCCTGTA | ||

| YWHAZ | NM_145690 | F(1133–1156) | ACTTTTGGTACATTGTGGCTTCAA |

| R(1226–1207) | CCGCCAGGACAAACCAGTAT |

F, Forward; R, reverse; YWHAZ, tyrosine 3-monooxygenase/tryptophan 5-monooxygenase activation protein, ζ polypeptide.

Statistics

Each experiment was performed in duplicate and repeated as detailed in each legend. Results are depicted by a representative experiment, and analyzed on the pooled data using the Primer of Biostatistics software package (McGraw-Hill, Inc., New York, NY) by either Kruskal-Wallis, one-way ANOVA with post hoc Dunnett’s test, or Mann-Whitney rank sum test, where appropriate. A value of P < 0.05 was determined significant.

Results

We initially determined the expression of CTGF protein in villi derived from human third trimester placentas, obtained after normal pregnancy and delivery. As shown in Fig. 1, A–C), we detected CTGF protein primarily in the trophoblast bilayer circumscribing the placental villi. CTGF immunoreactivity was also detected in cytotrophoblasts (Fig. 1D), endothelial cells (Fig. 1E), and, to a lesser degree, in some of the adjacent connective tissue cells within the villous core. For positive control we used a cross section of umbilical artery muscularis layer (Fig. 1F). The expression of CTGF protein in cultured trophoblasts was comparable in syncytia and in mononucleated cytotrophoblasts (Fig. 1G). We obtained a similar result using trophoblasts cultured for 72 h in either DMEM, which supports cytotrophoblasts differentiation into syncytium, or Ham’s-Waymouth medium, which hinders differentiation (31) (Fig. 1H).

Figure 1.

CTGF protein is expressed in the term human placenta. Formalin-fixed sections of normal term human placentas were stained for CTGF (A–C, magnification, ×200; B, bar, 50 μm) and counterstained with hematoxylin. A, No primary antibody control. B, CTGF expression was detected using goat anti-CTGF polyclonal antibody (1:50). C, Control in which the primary antibody was preincubated with a CTGF blocking peptide. D, Syncytiotrophoblast (white arrow) and cytotrophoblast (black arrow). E, Endothelial cells. F, Positive control for CTGF staining of umbilical artery muscularis layer (bar, 100 μm). G, Cultured PHT cells (72 h) stained using anti-CTGF (red) and antidesmosomal (green) antibodies as described in Materials and Methods. White arrows demonstrate CTGF expression in syncytia and in mononucleated cytotrophoblasts (bar, 3 μm). H, Western immunoblotting depicting CTGF protein expression in PHTs cultured in DMEM (D) or Ham’s-Waymouth (H) medium, performed as described in Materials and Methods (n = 3 for each panel).

To explore the influence of hypoxia on CTGF expression, we initially determined the time course of CTGF mRNA levels in PHT cells. Whereas the expression of CTGF transcript was gradually reduced in cells cultured in standard conditions for 72 h, hypoxia mitigated this reduction, resulting in a relative increase in the levels of CTGF mRNA after 24-h hypoxia (Fig. 2A). This effect was dependent on oxygen concentration, with a significant effect when FiO2 was reduced to less than or equal to 1%, but not 8% (Fig. 2B). We next determined if the hypoxia-induced increase in CTGF transcript resulted in higher levels of cellular CTGF protein. As shown in Fig. 3A, we found that cellular CTGF levels were unchanged when the cells were cultured in hypoxia up to 72 h. Because FBS contains CTGF and other growth factors that might have influenced cellular CTGF levels, we repeated this experiment in serum free conditions and found similar results (Fig. 3B), indicating that hypoxia does not change the steady-state level of intracellular CTGF protein in trophoblasts. Importantly, we found that hypoxia led to increased CTGF protein levels in serum free tissue culture medium. This increase was observed as early as 24 h in hypoxia and was sustained for 72 h in culture (Fig. 3C). The sodium-proton ionophore monensin, which disrupts protein secretion by neutralizing the intracellular acidic compartment of lysosomes and the trans-Golgi apparatus (32), attenuated the hypoxia-stimulated CTGF secretion (Fig. 3D). Together, our findings indicate that hypoxia enhances the expression of CTGF transcripts and the secretion of CTGF protein without altering intercellular CTGF protein levels in term PHT cells.

Figure 2.

Hypoxia regulates the expression of CTGF mRNA in human trophoblasts. PHT cells from term normal placentas were cultured in standard culture conditions (FiO2 = 20%) or in two conditions of reduced FiO2, 8% or less than or equal to 1%. CTGF transcript expression was determined using RT-qPCR as described in Materials and Methods. A, Time course for the effect of FiO2 less than or equal to 1%, depicting the fold change in CTGF expression between the two conditions (*, P < 0.05, Mann-Whitney U test; n = 5). B, The influence of oxygen concentration on the expression of CTGF transcript (*P < 0.05, Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA with post hoc Dunnett’s test; n = 3).

Figure 3.

Hypoxia increases the secretion of CTGF from human trophoblasts. PHT cells from term normal placentas were cultured in standard culture conditions (Std) (FiO2 = 20%) or in hypoxia (Hpx) (FiO2 ≤ 1%, n = 4). A and B, Cellular CTGF protein expression in cells cultured in serum-containing (A) or serum free (B) medium determined using Western immunoblotting as described in Materials and Methods. C, CTGF protein levels in serum free culture medium. D, The effect of monensin on hypoxia-stimulated CTGF secretion from trophoblasts cultured for 48 h in standard conditions or hypoxia (FiO2 ≤ 1%) in serum free medium in the presence or absence of monensin (*P < 0.05, ANOVA, n = 3, quantified as shown in the panel below the gel).

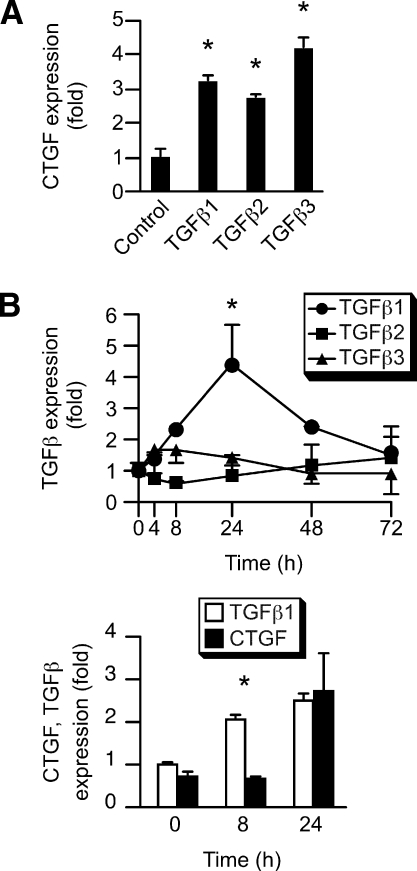

Because CTGF harbors HIF1α-binding hypoxia response elements upstream of CTGF coding sequences (33), we surmised that HIF1α regulates CTGF expression in PHT cells. We first determined that the hypoxia mimetic chemicals CoCl2 or DMOG, which stabilize HIF1α levels by inhibiting prolyl hydroxylation and subsequent ubiquitination, enhance CTGF expression. As shown in Fig. 4, A–C, both CoCl2 and DMOG enhanced the expression of CTGF transcript as well as secreted CTGF protein, but not cellular CTGF. As a control, we demonstrated that both chemicals also enhance the expression of HIF1α in primary trophoblasts (Fig. 4D). Consistent with these observations, we found that the expression of HIF1α is up-regulated in hypoxic trophoblast, and that the antiangiogenic chemical 2-methoxy-estradiol (2meE2) that reduces HIF1α levels in other cell systems (34) indeed diminished HIF1α expression in trophoblasts (Fig. 4E). When we exposed PHT cells to hypoxia, we found that 2meE2 mitigated the up-regulation of CTGF expression [with vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) as a positive control, Fig. 4F]. Because TGFβ isoforms are up-regulated in hypoxic trophoblasts (35,36,37,38) and were implicated in expression of CTGF, we examined the influence of TGFβ1, 2, or 3 on the expression of CTGF. As shown in Fig. 5, all three TGFβ isoforms enhanced the expression of CTGF in PHTs. Importantly, when we analyzed the time course of hypoxia-induced TGFβ expression in trophoblasts, we found that only the induction of TGFβ1 was consistent with the up-regulation of CTGF (Fig. 5B, upper panel). Moreover, the hypoxia-induced increase in TGFβ1 transcript temporally preceded that induction of CTGF transcript (Fig. 5B, lower panel). Together, our results buttress our findings regarding the influence of hypoxia on CTGF expression in human trophoblasts, and implicate HIF1α and TGFβ1 in the regulation of CTGF in PHT cells.

Figure 4.

HIF1α mediates the effect of hypoxia on CTGF in PHTs. Term PHT cells were cultured for 24 h in serum free medium in the absence or presence of CoCl2 (0, 0.1, 0.2 mm) or DMOG (0, 0.25, 0.5 μm). A, CTGF mRNA, measured using RT-qPCR (the influence of both chemicals was significant at P < 0.05). B, Intracellular CTGF protein. C, CTGF protein in the tissue culture medium. D, Intracellular HIF1α levels. E, The effect of hypoxia on HIF1α protein, in the presence or absence of 2meE2 (0, 0.1, 0.3, 1, 3 μm). F, The influence of 2meE2 on the expression of CTGF and VEGF (as a control) in standard culture conditions (Std) (FiO2 = 20%) or in hypoxia (Hpx) (FiO2 ≤ 1%), determined using RT-qPCR. Cells were cultured for 12 h in the absence or presence of 2meE2 (0, 0.1, 1, 10 μm), and then exposed to hypoxia for 24 h (*, P < 0.05, Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA with post hoc Dunnett’s test; n = 3).

Figure 5.

TGFβ regulates CTGF expression in PHTs. PHT cells were cultured in serum free medium, and the expression of CTGF or TGFβ isoforms was measured using RT-qPCR. A, The influence of TGFβ1, TGFβ2, or TGFβ3 (10 ng/ml each, 24 h) on CTGF mRNA expression (*, P < 0.05, Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA with post hoc Dunnett’s test; n = 3). B, Time course for the effect of hypoxia (FiO2 ≤ 1%) on the expression of TGFβ isoforms (upper panel), or specifically on TGFβ1 and CTGF (lower panel) in the first 24-h PHT culture (*, P < 0.05, Mann-Whitney U test; n = 3).

Finally, we sought to determine whether CTGF influences the expression of mediators of fibrosis or hypoxia-related transcripts within PHT cells. The addition of recombinant full-length CTGF (0.125–0.25 μg/kg) or the 98 aa C-terminal domain of CTGF (1–4 μg/kg) (39) to cultured term PHT cells, in the absence or presence of serum for 24–48 h, had no effect on cell morphology or on the expression of mRNA for VEGF, N-Myc down-regulated gene 1, erythropoietin, transferring receptor, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) MMP2 and MMP3, and their tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases 1–4, yet CTGF increased the level of transcripts for MMP3 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 2 in the IMR-90 fibroblast line, used as a control (data not shown).

Discussion

We analyzed the expression of CTGF in human third trimester villous tissue, and found that CTGF protein was expressed primarily in trophoblasts, villous endothelial cells, and, to a lesser degree, in some of the adjacent connective tissue cells within the villous core. The uniform expression pattern of CTGF protein throughout the culture period in conditions that either support or hinder trophoblast differentiation (12) bolsters the finding that CTGF is expressed in both differentiated syncytiotrophoblasts and undifferentiated cytotrophoblasts. Importantly, whereas CTGF mRNA levels decrease as trophoblasts differentiate in culture, hypoxia reverses the decline in CTGF, resulting in a higher level of CTGF mRNA in cells cultured in FiO2 less than or equal to 1%, compared with cells cultured in FiO2 of either 20 or 8%. Interestingly, Higgins et al. (33) found that primary renal tubular epithelial cells exhibited an increase in CTGF mRNA in response to hypoxia, without an initial decline as we observed in human trophoplasts. This difference in the influence of hypoxia on CTGF may reflect the different cell types used in these studies and a difference in the experimental time course between the two cell systems.

CTGF is secreted after processing in the Golgi (40,41). We found that although the level of intracellular CTGF protein remained stable in hypoxic trophoblasts, medium levels of CTGF were increased by hypoxia. This increase was attenuated in a concentration-dependent manner by monensin, which inhibits protein transport at the trans-Golgi (32,42). These findings suggest that in addition to its effect on increasing CTGF mRNA, hypoxia enhances the secretion of CTGF from trophoblasts. However, monensin does not completely block the increase in protein secretion, implying that other mechanisms contribute to the increase in extracellular CTGF protein levels.

Several observations also support a role for HIF1α in hypoxia-dependent stimulation of CTGF expression and secretion: 1) HIF1α expression is enhanced concomitantly with CTGF transcript in PHT cells; 2) the hypoxia-mimetics CoCl2 and DMOG, which diminish HIF1α degradation, recapitulate the effect of hypoxia on CTGF mRNA expression and CTGF protein secretion; and 3) 2meE2, which degrades HIF1α protein, attenuates the hypoxia-induced increase in CTGF expression. Whereas hypoxia alters the secretion of CTGF from several cell types (33,43,44,45,46), this is the first description of CTGF protein expression and secretion from human trophoblasts in response to hypoxia. CTGF is regulated by hypoxia via at least two distinct mechanisms: 1) binding of HIF1α to two hypoxia responsive elements (−3745/3741 and −1558/1554 sites) in the 5′-sequences of the murine CTGF gene and enhancing promoter activity in murine primary tubular epithelial cells (33); and 2) regulation of CTGF mRNA via the cis-acting element of structure-anchored repression, located within the 3′untranslated region of CTGF gene (44). Interestingly, CTGF has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of hyperoxia-induced lung fibrosis in a rat model (47), as well as fibrosis in other, nonplacental tissues. Several modulators of fibrosis (e.g. fibronectin, MMPs) are known targets for CTGF (48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56). The exact cellular and molecular targets for CTGF action within the placenta, and the potential role of CTGF in placental fibrosis, remain unknown. Moreover, the lack of effect of CTGF on extracellular matrix-related transcripts within trophoblasts suggests that CTGF, secreted from injured trophoblasts, may influence other villous cell types. Alternatively, CTGF may function as an adaptor molecule that modulates the action of other ligands, such as TGFβ, epidermal growth factor, and VEGF, on membrane receptors (19,57,58,59).

Our data regarding the effect of TGFβ on the expression of CTGF is consistent with previous observations, which demonstrated that TGFβ is a potent stimulus of CTGF expression and regulates CTGF in a cell-dependent manner (56,58,60,61). Consistent with these data, silencing of CTGF attenuates some of the pro-fibrosis effects of TGFβ (62). Because CTGF mimics many of the actions of TGFβ, and TGFβ signaling commonly transduces the impact of hypoxia to cells, including trophoblasts, it is tempting to assume that TGFβ mediates the influence of hypoxia on CTGF (37,38). In contrast, up-regulation of CTGF during adaptation to injury, including hypoxia, may be independent of TGFβ or small mothers against decapentaplegic (SMAD) protein signaling (33,63). It remains to be established if TGFβ, hypoxia, and other signaling pathways cooperatively regulate CTGF when trophoblasts are exposed to cellular injury.

Acknowledgments

We thank Elena Sadovsky for technical assistance and Lori Rideout for assistance during preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Grants R01-HD29190 (to D.M.N.) and R01-HD45675 (to Y.S.) from the National Institute of Health, and R01ES011597 (to Y.S.) from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

Results from this work were presented in part at the 53rd Annual Meeting of the Society for Gynecologic Investigation, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2006.

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online February 21, 2008

Abbreviations: CCN, CTGF, Cyr61, and Nov; CoCl2, Cobalt chloride; CTGF, connective tissue growth factor; DMOG, dimethyloxaloylglycine; FBS, fetal bovine serum; FGR, fetal growth restriction; HIF, hypoxia-inducible factor; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; 2meE2, 2-methoxy-estradiol; PHT, primary human trophoblast; RT-qPCR, quantitative RT-PCR; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

References

- Kingdom JCP, Jauniaux ERM, O'Brien PMS 2000 The placenta: basic science and clinical practice. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Press [Google Scholar]

- Rinkenberger J, Werb Z 2000 The labyrinthine placenta. Nat Genet 25:248–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnik R 2002 Intrauterine growth restriction. Obstet Gynecol 99:490–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardi G, Marconi AM, Cetin I 2002 Placental-fetal interrelationship in IUGR fetuses—a review. Placenta 23(Suppl A):S136–S141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valsamakis G, Kanaka-Gantenbein C, Malamitsi-Puchner A, Mastorakos G 2006 Causes of intrauterine growth restriction and the postnatal development of the metabolic syndrome. Ann NY Acad Sci 1092:138–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saenger P, Czernichow P, Hughes I, Reiter EO 2007 Small for gestational age: short stature and beyond. Endocr Rev 28:219–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodesch F, Simon P, Donner C, Jauniaux E 1992 Oxygen measurements in endometrial and trophoblastic tissues during early pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 80:283–285 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genbacev O, Joslin R, Damsky CH, Polliotti BM, Fisher SJ 1996 Hypoxia alters early gestation human cytotrophoblast differentiation/invasion in vitro and models the placental defects that occur in preeclampsia. J Clin Invest 97:540–550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genbacev O, Zhou Y, Ludlow JW, Fisher SJ 1997 Regulation of human placental development by oxygen tension. Science 277:1669–1672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jauniaux E, Watson A, Burton G 2001 Evaluation of respiratory gases and acid-base gradients in human fetal fluids and uteroplacental tissue between 7 and 16 weeks’ gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol 184:998–1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benyo DF, Miles TM, Conrad KP 1997 Hypoxia stimulates cytokine production by villous explants from the human placenta. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82:1582–1588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DM, Johnson RD, Smith SD, Anteby EY, Sadovsky Y 1999 Hypoxia limits differentiation and up-regulates expression and activity of prostaglandin H synthase 2 in cultured trophoblast from term human placenta. Am J Obstet Gynecol 180:896–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy R, Smith SD, Chandler K, Sadovsky Y, Nelson DM 2000 Apoptosis in human cultured trophoblasts is enhanced by hypoxia and diminished by epidermal growth factor. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 278:C982–C988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Nelson DM, Sadovsky Y 2006 N-Myc downregulated gene 1 (Ndrg1) modulates the response of term human trophoblasts to hypoxic injury. J Biol Chem 281:2764–2772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingdom J 1998 Placental pathology in obstetrics: adaptation or failure of the villous tree? Placenta 19:347–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benirschke K, Kaufmann P2000 Pathology of the human placenta. 4th ed. New York: Springer [Google Scholar]

- Budhraja V, Spitznagel E, Schaiff WT, Sadovsky Y 2003 Incorporation of gene-specific variability improves expression analysis using high-density DNA microarrays. BMC Biol 1:1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roh CR, Budhraja V, Kim HS, Nelson DM, Sadovsky Y 2005 Microarray-based identification of differentially expressed genes in hypoxic term human trophoblasts and in placental villi of pregnancies with growth restricted fetuses. Placenta 26:319–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leask A, Abraham DJ 2006 All in the CCN family: essential matricellular signaling modulators emerge from the bunker. J Cell Sci 119:4803–4810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perbal BV, Takigawa M2005 CCN proteins: a new family of cell growth and differentiation regulators. London: World Scientific Publishers [Google Scholar]

- Brigstock DR 2003 The CCN family: a new stimulus package. J Endocrinol 178:169–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surveyor GA, Wilson AK, Brigstock DR 1998 Localization of connective tissue growth factor during the period of embryo implantation in the mouse. Biol Reprod 59:1207–1213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kireeva ML, Latinkic BV, Kolesnikova TV, Chen CC, Yang GP, Abler AS, Lau LF 1997 Cyr61 and Fisp12 are both ECM-associated signaling molecules: activities, metabolism, and localization during development. Exp Cell Res 233:63–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivkovic S, Yoon BS, Popoff SN, Safadi FF, Libuda DE, Stephenson RC, Daluiski A, Lyons KM 2003 Connective tissue growth factor coordinates chondrogenesis and angiogenesis during skeletal development. Development 130:2779–2791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi T, Yamaai T, Asano M, Nawachi K, Suzuki M, Sugimoto T, Takigawa M 2001 Overexpression of connective tissue growth factor/hypertrophic chondrocyte-specific gene product 24 decreases bone density in adult mice and induces dwarfism. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 281:678–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo FE, Muntean AG, Chen CC, Stolz DB, Watkins SC, Lau LF 2002 CYR61 (CCN1) is essential for placental development and vascular integrity. Mol Cell Biol 22:8709–8720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliman HJ, Nestler JE, Sermasi E, Sanger JM, Strauss 3rd JF 1986 Purification, characterization, and in vitro differentiation of cytotrophoblasts from human term placentae. Endocrinology 118:1567–1582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaiff WT, Bildirici I, Cheong M, Chern PL, Nelson DM, Sadovsky Y 2005 Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ and retinoid X receptor signaling regulate fatty acid uptake by primary human placental trophoblasts. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:4267–4275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meller M, Vadachkoria S, Luthy DA, Williams MA 2005 Evaluation of housekeeping genes in placental comparative expression studies. Placenta 26:601–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD 2001 Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25:402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas GC, King BF 1990 Differentiation of human trophoblast cells in vitro as revealed by immunocytochemical staining of desmoplakin and nuclei. J Cell Sci 96:131–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollenhauer HH, Morre DJ, Rowe LD 1990 Alteration of intracellular traffic by monensin; mechanism, specificity and relationship to toxicity. Biochim Biophys Acta 1031:225–246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins DF, Biju MP, Akai Y, Wutz A, Johnson RS, Haase VH 2004 Hypoxic induction of Ctgf is directly mediated by Hif-1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287:F1223–F1232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooberry SL 2003 Mechanism of action of 2-methoxyestradiol: new developments. Drug Resist Updat 6:355–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel B, Khaliq A, Jarvis-Evans J, McLeod D, Mackness M, Boulton M 1994 Oxygen regulation of TGF-β1 mRNA in human hepatoma (Hep G2) cells. Biochem Mol Biol Int 34:639–644 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi QJ, Lei ZM, Rao CV, Lin J 1993 Novel role of human chorionic gonadotropin in differentiation of human cytotrophoblasts. Endocrinology 132:1387–1395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caniggia I, Mostachfi H, Winter J, Gassmann M, Lye SJ, Kuliszewski M, Post M 2000 Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 mediates the biological effects of oxygen on human trophoblast differentiation through TGFβ(3). J Clin Invest 105:577–587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Akman HO, Smith EL, Zhao J, Murphy-Ullrich JE, Batuman OA 2003 Cellular response to hypoxia involves signaling via Smad proteins. Blood 101:2253–2260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao R, Brigstock DR 2004 Connective tissue growth factor (CCN2) induces adhesion of rat activated hepatic stellate cells by binding of its C-terminal domain to integrin α(v) β(3) and heparan sulfate proteoglycan. J Biol Chem 279:8848–8855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Segarini P, Raoufi F, Bradham D, Leask A 2001 Connective tissue growth factor is secreted through the Golgi and is degraded in the endosome. Exp Cell Res 271:109–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicha I, Garlichs CD, Daniel WG, Goppelt-Struebe M 2004 Activated human platelets release connective tissue growth factor. Thromb Haemost 91:755–760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flieger O, Engling A, Bucala R, Lue H, Nickel W, Bernhagen J 2003 Regulated secretion of macrophage migration inhibitory factor is mediated by a non-classical pathway involving an ABC transporter. FEBS Lett 551:78–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo S, Kubota S, Shimo T, Nishida T, Yosimichi G, Eguchi T, Sugahara T, Takigawa M 2002 Connective tissue growth factor increased by hypoxia may initiate angiogenesis in collaboration with matrix metalloproteinases. Carcinogenesis 23:769–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo S, Kubota S, Mukudai Y, Moritani N, Nishida T, Matsushita H, Matsumoto S, Sugahara T, Takigawa M 2006 Hypoxic regulation of stability of connective tissue growth factor/CCN2 mRNA by 3′-untranslated region interacting with a cellular protein in human chondrosarcoma cells. Oncogene 25:1099–1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong KH, Yoo SA, Kang SS, Choi JJ, Kim WU, Cho CS 2006 Hypoxia induces expression of connective tissue growth factor in scleroderma skin fibroblasts. Clin Exp Immunol 146:362–370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olbryt M, Jarzab M, Jazowiecka-Rakus J, Simek K, Szala S, Sochanik A 2006 Gene expression profile of B 16(F10) murine melanoma cells exposed to hypoxic conditions in vitro. Gene Expr 13:191–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CM, Wang LF, Chou HC, Lang YD, Lai YP 2007 Up-regulation of connective tissue growth factor in hyperoxia-induced lung fibrosis. Pediatr Res 62:128–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- di Mola FF, Friess H, Martignoni ME, Di Sebastiano P, Zimmermann A, Innocenti P, Graber H, Gold LI, Korc M, Buchler MW 1999 Connective tissue growth factor is a regulator for fibrosis in human chronic pancreatitis. Ann Surg 230:63–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y, Aten J, Bende RJ, Oemar BS, Rabelink TJ, Weening JJ, Goldschmeding R 1998 Expression of connective tissue growth factor in human renal fibrosis. Kidney Int 53:853–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoi H, Mukoyama M, Sugawara A, Mori K, Nagae T, Makino H, Suganami T, Yahata K, Fujinaga Y, Tanaka I, Nakao K 2002 Role of connective tissue growth factor in fibronectin expression and tubulointerstitial fibrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 282:F933–F942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CC, Chen N, Lau LF 2001 The angiogenic factors Cyr61 and connective tissue growth factor induce adhesive signaling in primary human skin fibroblasts. J Biol Chem 276:10443–10452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman JT, Clark IM, Garcia PL 2000 Hypoxia promotes fibrogenesis in human renal fibroblasts. Kidney Int 58:2351–2366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahab NA, Yevdokimova N, Weston BS, Roberts T, Li XJ, Brinkman H, Mason RM 2001 Role of connective tissue growth factor in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. Biochem J 359(Pt 1):77–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonniaud P, Martin G, Margetts PJ, Ask K, Robertson J, Gauldie J, Kolb M 2004 Connective tissue growth factor is crucial to inducing a profibrotic environment in “fibrosis-resistant” BALB/c mouse lungs. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 31:510–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaney Davidson EN, Vitters EL, Mooren FM, Oliver N, Berg WB, van der Kraan PM 2006 Connective tissue growth factor/CCN2 overexpression in mouse synovial lining results in transient fibrosis and cartilage damage. Arthritis Rheum 54:1653–1661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotendorst GR 1997 Connective tissue growth factor: a mediator of TGF-β action on fibroblasts. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 8:171–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abreu JG, Ketpura NI, Reversade B, De Robertis EM 2002 Connective-tissue growth factor (CTGF) modulates cell signalling by BMP and TGF-β. Nat Cell Biol 4:599–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori T, Kawara S, Shinozaki M, Hayashi N, Kakinuma T, Igarashi A, Takigawa M, Nakanishi T, Takehara K 1999 Role and interaction of connective tissue growth factor with transforming growth factor-β in persistent fibrosis: a mouse fibrosis model. J Cell Physiol 181:153–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi-wen X, Stanton LA, Kennedy L, Pala D, Chen Y, Howat SL, Renzoni EA, Carter DE, Bou-Gharios G, Stratton RJ, Pearson JD, Beier F, Lyons KM, Black CM, Abraham DJ, Leask A 2006 CCN2 is necessary for adhesive responses to transforming growth factor-β1 in embryonic fibroblasts. J Biol Chem 281:10715–10726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotendorst GR, Okochi H, Hayashi N 1996 A novel transforming growth factor beta response element controls the expression of the connective tissue growth factor gene. Cell Growth Differ 7:469–480 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leask A, Holmes A, Black CM, Abraham DJ 2003 Connective tissue growth factor gene regulation. Requirements for its induction by transforming growth factor-β2 in fibroblasts. J Biol Chem 278:13008–13015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi W, Chen X, Polhill TS, Sumual S, Twigg S, Gilbert RE, Pollock CA 2006 TGF-β1 induces IL-8 and MCP-1 through a connective tissue growth factor-independent pathway. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290:F703–F709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes A, Abraham DJ, Sa S, Shiwen X, Black CM, Leask A 2001 CTGF and SMADs, maintenance of scleroderma phenotype is independent of SMAD signaling. J Biol Chem 276:10594–105601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]