Abstract

Response gene to complement 32 (Rgc32) has recently been suggested to be expressed in the ovary and regulated by RUNX1, a transcription factor in periovulatory follicles. In the present study, we determined the expression profile of the Rgc32 gene in the rodent ovary throughout the reproductive cycle and the regulatory mechanism(s) involved in Rgc32 expression during the periovulatory period. Northern blot and in situ hybridization analyses revealed the up-regulation of Rgc32 expression in periovulatory follicles. Rgc32 mRNA was also localized to newly forming corpora lutea (CL) and CL from previous estrous cycles. Further studies using hormonally induced luteal and luteolysis models revealed a transient increase in levels of Rgc32 mRNA at the time of functional regression of the CL. Next, the regulation of Rgc32 expression was investigated in vitro using rat preovulatory granulosa cells. The effect of human chorionic gonadotropin on Rgc32 expression was mimicked by forskolin, but not phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, and was mediated by the activation of progesterone receptors and the epidermal growth factor-signaling pathway. The mechanism by which RUNX1 regulates Rgc32 expression was investigated using chromatin immunoprecipitation and Rgc32 promoter-luciferase reporter assays. Data from these assays revealed direct binding of RUNX1 in the Rgc32 promoter region in vivo as well as the involvement of RUNX binding sites in the transactivation of the Rgc32 promoter in vitro. In summary, the present study demonstrated the spatial/temporal-specific expression of Rgc32 in the ovary, and provided evidence of LH-initiated and RUNX1-mediated expression of Rgc32 gene in luteinizing granulosa cells.

IN RESPONSE TO the LH/FSH surge, a preovulatory follicle embarks on a terminal differentiation pathway (luteinization) that transforms granulosa and theca cells of a preovulatory follicle into luteal cells to form a corpus luteum. Luteinizing follicular cells undergo specific morphological changes (e.g. compact, nuclear-dominant cells to become loosely connected hypertrophic cells) as well as physiological alterations in their transition to luteal cells. These changes include withdrawal from the cell cycle in proliferating granulosa cells and a rapid shift in steroidogenesis from estradiol/androstenedione to progesterone (reviewed in Refs. 1,2,3). These changes are mediated by coordinate regulation of the genes encoding various cell cycle modulators (e.g. Ccnd2, Cdkn1a, and Cdkn1b) and steroidogenic factors (e.g. Star and Cyp11a1) in periovulatory follicular cells. Recently, we detected the up-regulation of response gene to complement 32 (Rgc32) expression in rat granulosa cells treated with human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) in vitro (4). Furthermore, knockdown of hCG-induced RUNX1 by small interfering RNA reduced levels of Rgc32 mRNA. The transcription factor RUNX1 is known to play an important role in ensuring the coordinate transition from proliferation to differentiation in a wide variety of cells (reviewed in Ref. 5). Previous studies from our laboratory and others demonstrated the dramatic up-regulation of this transcription factor in periovulatory follicles after the LH/FSH surge (4,6). Rgc32 was initially identified as a gene induced in oligodendrocytes in response to sublytic complement activation (7) and has since been implicated as a cell cycle regulatory molecule (8,9). A recent study by Li et al. (10) demonstrated that Rgc32 expression was important for vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation. Together, these findings suggest that Rgc32 expression may be regulated by RUNX1, and RGC32 may be involved in the luteinization process, perhaps by acting as a cell cycle modulator. However, nothing is known about in vivo expression of Rgc32 as well as the regulation of Rgc32 expression by RUNX1 or other LH-induced mediators in the ovary.

Given that ovarian follicular cells undergo dynamic changes in the cell cycle during follicular development and luteinization, it is conceivable that RGC32 is expressed in follicular and/or luteal cells, and its expression is regulated during this critical period in a manner to impact the cell cycle transition. Therefore, in the present study, we determined the expression pattern of Rgc32 throughout the reproductive cycle using ovaries from pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (PMSG)/hCG-primed immature mice and rats, as well as ovaries from cycling rats. After characterization of the Rgc32 expression pattern, we investigated the cellular/molecular mechanism(s) by which Rgc32 expression is regulated in the ovary using both in vivo and in vitro experimental models.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Unless otherwise noted, all chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Molecular biological enzymes, molecular size markers, oligonucleotide primers, pCRII-TOPO Vector, culture media, and TRIzol were purchased from Invitrogen Life Technologies, Inc. (Carlsbad, CA).

Animals

All animal procedures were approved by the University of Kentucky Animal Care and Use Committee. In the present study, gonadotropin-treated immature female rats and mice, as well as sexually mature adult female rats exhibiting regular 4-d estrous cycles were used. Sprague Dawley rats and C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Harlan, Inc. (Indianapolis, IN), and provided with water and chow ad libitum.

For the gonadotropin-induced preovulatory model, animals were maintained on a 12-h light, 12-h dark cycle. The animals (22 or 23 d old) were injected with PMSG (10 IU to rats and 5 IU to mice) sc to stimulate follicular development. Forty-eight hours later, the rats and mice were injected with hCG (10 IU to rats and 5 IU to mice) sc to induce ovulation and subsequent formation of corpora lutea (CL). In this model (11), ovulation occurs approximately 12–16 h after hCG administration. Animals were killed at 0 h (at hCG administration) and defined times after hCG administration (n = 3–4 animals per time point). Ovaries were collected and stored at −70 C for later extraction of total RNA, or placed in optimum cutting temperature compound (VWR Scientific, Atlanta, GA), snap frozen, and stored at −70 C until sectioned and processed for in situ hybridization analyses.

Adult female Sprague Dawley rats (150–180 g body weight, 2 months old) were purchased from Harlan, Inc., and housed as described previously. Stages of the estrous cycle were determined by daily examination of vaginal cytology, and only animals showing at least 2 consecutive 4-d cycles were used for the experiment. Rats were killed at 1600 and 2000 h on proestrus, and 0400 h on estrus. In this colony of rats, the LH surge occurred at 1600 h on proestrus. Ovaries were collected, placed in optimum cutting temperature compound, and stored at −70 C until sectioned and processed for in situ hybridization analyses.

To assess the expression pattern of Rgc32 during the luteal period, we used the models of gonadotropin-induced pseudopregnancy (PSP) (12,13), as well as the induced-functional and subsequent structural luteolysis based on the ablation or replacement of the prolactin (PRL) method (14,15). Ovulation and PSP were induced in immature (21 d old) rats by injection of PMSG (10 IU), followed 48 h later with hCG (10 IU). For the gonadotropin-induced PSP model, ovaries were collected on 1, 4, 8, 12, 18, 21, or 23 d after hCG injection. In this model the ovulated follicles transformed into CL that remained functional for 9 ± 1 d and then regressed (12). For the induced-functional and subsequent structural luteolysis model, starting on d-4 PSP (PSP4) through d-10 PSP (PSP10), rats were injected twice daily (0900 and 1900 h) with 2-bromo-α-ergocryptine (bromocriptine) to block endogenous PRL release and induce functional luteolysis (0.5 mg sc in saline with 0.3% tartaric acid and 10% ethanol). Control animals (n = 4) received vehicle. To induce structural luteolysis, PRL (10 IU) was injected concomitantly with bromocriptine treatment from d-7 PSP (PSP7) (1900 h) to PSP10 (1900 h); control animals received bromocriptine and PRL vehicle (saline). Five experimental groups (n = 5) were thus defined: group 1, animals with functional CL collected on the morning of PSP4; groups 2 and 3, animals exposed to vehicle or bromocriptine from PSP4 (0900 h) to PSP7 (1900 h) and collected at PSP7 (functional or functionally regressed CL, respectively); and groups 4 and 5, animals injected with bromocriptine from PSP4 (0900 h) to PSP10 (1900 h) and PRL or vehicle (saline) from PSP7 (0900 h) to PSP10 (1900 h), and collected at PSP10 (functionally and structurally regressed CL or functionally regressed, structurally normal CL, respectively). Ovaries and blood samples were collected and stored at −70 C for later assays.

Concentrations of progesterone in serum collected from rats were measured using an Immulite kit (Diagnostic Products Corp., Los Angeles, CA). Assay sensitivity was 0.02 ng/ml. The intraassay and interassay coefficients of variation were 9.6 and 10%, respectively.

Isolation and culture of rat granulosa cells

To isolate granulosa cells, ovaries were collected from immature rats 48 h after PMSG administration and processed as described previously (16). Briefly, granulosa cells were isolated by the method of follicular puncture. The cells were pooled, filtered, pelleted by centrifugation at 200 × g for 5 min, and resuspended in defined medium consisting of DMEM-Ham’s F-12 medium supplemented with 1% BSA, 0.01% pyruvic acid, 0.22% bicarbonate, 0.05 mg/ml gentamycin, and 1× insulin, transferrin, and selenium. The cells were cultured in the absence or presence of various reagents for 0, 3, 6, 12, or 24 h at 37 C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. When reagents were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) or ethyl alcohol (EtOH), the same concentrations of DMSO or EtOH were added to the medium for the control cells. The final concentration of DMSO or EtOH in cultures was less than 0.1%. At the end of each culture period, cells were collected and snap frozen for later isolation of total RNA.

Isolation of rat cumulus oocyte complexes (COCs)

To obtain COCs from rats, ovaries were collected from PMSG-primed immature rats at 0 h (48 h after PMSG), 6, 12, or 18 h after hCG injection, punctured using 26-gauge needles, and gently pressed to release COCs from preovulatory follicles in DMEM-Ham’s F-12 medium. COCs of appropriate conditions (e.g. nonexpanded with multiple layers of cumulus granulosa cells attached COCs at 0 h, semi-expanded COCs at 6 h, and fully expanded COCs at 12 h after hCG) were collected using a 20-μl pipette, pooled, and stored at −80 C for later isolation of total RNA. To obtain ovulated and fully expanded COCs, the oviducts of gonadotropin-stimulated immature rats were removed 18 h after hCG injection. The COCs were released by gently teasing apart the ampulla of oviducts and collected using a 200-μl pipette. The COCs were pooled from 10 animals per time point to obtain enough total RNA for the gene expression experiment, and the collections were repeated three times (n = 3 experiments per time points).

Collection of granulosa cells from women

Human granulosa cells were obtained from women undergoing in vitro fertilization. Briefly, patients (30–42 yr old, n = 4) were treated with a GnRH agonist (Lupron; TAP Pharmaceutical Products, Inc., Lake Forest, IL) beginning during the luteal phase of the preceding cycle for pituitary desensitization. After menses occurred, patients were then given recombinant FSH (Gonal-f; Serono, Inc., Rockland, MA) for 7–11 d in individualized doses to induce appropriate follicular growth, as determined by frequent ultrasound examinations and serum estradiol monitoring. When the two largest follicles reached an average diameter of more than or equal to 18 mm, hCG (250 μg, Ovidrel; Serono, Inc.) was administrated sc, and ultrasound-guided follicular aspiration was performed 36 h later. COCs were removed from the aspirates, and the remaining fluid containing the granulosa cells was collected and snap frozen for later isolation of total RNA. All patients gave informed consent before the procedure. This study was approved by the Medical Institutional Review Board of the University of Kentucky.

Culture and treatment of ovarian cell lines

Three ovarian cancer cell lines, CaOV-3, SK-OV-3, and OVCAR-3, were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and cultured in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2, 95% air at 37 C. Briefly, CaOV-3 cells were maintained in defined medium consisting of DMEM with 4 mm l-glutamine adjusted to contain 1.5 g/liter sodium bicarbonate and 4.5 g/liter glucose, and supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). SK-OV-3 cells were maintained in defined medium consisting of McCoy’s 5A medium with 1.5 mm l-glutamine adjusted to contain 2.2 g/liter sodium bicarbonate and supplemented with 10% FBS. OVCAR-3 cells were maintained in defined medium consisting of RPMI 1640 with 2 mm l-glutamine adjusted to contain 1.5 g/liter sodium bicarbonate, 4.5 g/liter glucose, 10 mm HEPES, 1.0 mm sodium pyruvate, and supplemented with 20% FBS. All media and supplements were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. The cells were passaged with 0.06% trypsin/0.13 mm EDTA in Mg2+/Ca2+-free Hanks’ balanced salt solution at confluence. To investigate the levels of Rgc32 and p53 mRNA, the cells were plated on six-well plates after reaching 70–80% confluency and cultured for a further 24 h. At the end of culture period, the cells were harvested and stored at −70 C for later isolation of total RNA. The experiments were repeated at least three times.

Quantification of Rgc32 mRNA

Total RNA was isolated from whole ovaries collected during the periovulatory period and the luteal period, as well as from cultured granulosa cells and COCs using TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol and quantified by spectrophotometry. To measure the levels of Rgc32 mRNA in whole ovaries or granulosa cells, Northern blot analyses were performed as described previously (4). Plasmids containing rat cDNAs for Rgc32 (4) and mouse cDNA for ribosomal protein L32 (kindly provided by Dr. O. K. Park-Sarge, University of Kentucky) were linearized with EcoRV and EcoRI, respectively. Antisense riboprobes were transcribed using [α-32P]uridine 5′-triphosphate (10 mCi/ml; New England Nuclear Life Science Products brand from PerkinElmer, Boston, MA) and SP6 or T7 RNA polymerase (Ambion, Inc. Austin, TX), as appropriate. Northern membranes were hybridized with 32P-labeled antisense riboprobes in Ultrahyb hybridization buffer (Ambion) at 68 C for at least 16 h. Excess probe was removed by washing with a stringent buffer (0.1× standard saline citrate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate) twice at 68 C for 60 min. The membrane was exposed to a phosphorimaging plate and quantified with a phosphorimager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). The relative levels of Rgc32 mRNA were normalized to L32 mRNA levels via dividing the band intensity of Rgc32 mRNA by the band intensity of L32 mRNA in each lane.

To measure levels of Rgc32 mRNA in COCs, human luteinizing granulosa cells, and ovarian cancer cell lines, we used real-time PCR, therefore, overcoming the limitation of the small quantity of total RNA isolated from these samples. Briefly, total RNA was treated with 0.2U DNase I to eliminate possible contamination with genomic DNA. Synthesis of first-strand cDNA was performed by RT of 0.5 μg total RNA using superScript III with Olido(dT)20 primer according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen Life Technologies). Oligonucleotide primers corresponding to cDNA for rat L32 (accession no. BC061562, forward 5′-GAA GCC CAA GAT CGT CAA AA-3′, reverse 5′-AGG ATC TGG CCC TGG CCC TTG AAT CT-3′), human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (forward 5′-ATG GAA ATC CCA TCA CCA TCT T-3′, reverse 5′-CGC CCC ACT TGA TTT TGG-3′), and Rgc32 (accession no. AF036548, forward 5′-TGA ATT CTC CGA CGG ACT CCA C-3′, reverse 5′-ATC AGC GAT GAA GTC TTC GAG C-3′ for rats; accession no. NM014059, forward 5′-AGT TCT GGG TCC TTT CAT CA-3′, reverse 5′-TGG CCT GGT AGA AGG TTG AG-3′ for human) were designed using PRIMER3 software, and the specificity for each primer set was confirmed by both running the PCR products on a 2.0% agarose gel and analyzing the melting (dissociation) curve using the MxPro Real-time PCR analysis program (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) after each real-time PCR. The real-time PCRs contained 10% RT reaction product, 0.4 μm forward and reverse primers, 0.3 μl 1:10 diluted ROX reference dye (provided with SYBR Green ER qPCR SuperMix Universal kit; Invitrogen Life Technologies), and SYBR Green SuperMix. PCRs were performed on the Mx3000P QPCR System (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The thermal cycling steps include 2 min at 50 C to permit optimal AmpErase uracil-N-glycosylase activity, 10 min at 95 C for initial denaturation, and then each cycle was 15 sec at 95 C, 30 sec at 58 C, and 30 sec at 72 C for 40 cycles, followed by 1 min at 95 C, 30 sec at 58 C, and then 30 sec at 95 C for ramp dissociation. The relative amount of transcripts was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method (17) and normalized to the endogenous reference gene L32.

In situ hybridization of Rgc32 mRNA

Ovaries collected from naturally cycling adult rats were sectioned at 10 μm and mounted on Probe On Plus slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). In situ hybridization was performed as described previously (18). Briefly, plasmids containing cDNA for rat Rgc32 were linearized with BamHI and EcoRV to generate sense and antisense riboprobes, respectively. Linearized plasmids were labeled with [α-35S]uridine 5′-triphosphate (10 mCi/ml; MP Biomedicals, Inc., Costa Mesa, CA), and T7 and SP6 RNA polymerases, as appropriate. One ovary from each of three animals was used for in situ hybridization. At least four sections per ovary were analyzed for each antisense probe, making a total of at least 12 tissue sections analyzed for each time point. A sense riboprobe, used as a control for nonspecific binding, was included for each ovary and each time point.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis

ChIP assay was performed on RUNX1 binding sites in the Rgc32 promoter region using a ChIP-IT kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA) and a ChIP kit (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc., Lake Placid, NY) according to the manufacturer’s protocol with minor modifications. A nonspecific normal rabbit IgG was used in ChIP reactions as a negative control to show the binding specificity of RUNX1 proteins to the Rgc32 promoter region. Briefly, granulosa cells were treated with 1% formaldehyde in PBS for 10 min to cross-link the protein-protein and protein-DNA in the cells. Cross-linking was stopped by adding glycine stop solution (provided with the ChIP-IT kit). Cells were pelleted by centrifugation and lysed in 1 ml ice-cold lysis buffer plus 5 μl proteinase inhibitor cocktail and 5 μl phenyl methyl sulfonyl fluoride (100 mm, supplied with the kit). The mixture was incubated for 30 min and gently homogenized on ice to release nuclei from the cells. The nuclei were sonicated in 1 ml shearing buffer at a 2.5 power level for 20 min with 20-sec sonication and 30-sec intervals with a Fisher Sonic Dismembrator Model 550 to obtain DNA fragments of an average length of approximately 100–500 bp. Chromatin was immunoprecipitated overnight at 4 C with anti-RUNX1 (5 μg/reaction; Calbiochem, Novabiochem Corp., La Jolla, CA) or normal rabbit IgG (5 μg/reaction; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA). The immunoprecipitated chromatin and 1:10 dilution of input chromatin were analyzed by PCR using the primers designed to amplify fragments of the RUNX motif in the Rgc32 promoter [see Fig. 8, RUNX−1136 (forward 5′-CAA ACT CAG GGC TTA CCC ATT-3′, reverse 5′-AAA CTG GAA GGA CAC CCA TT-3′), RUNX−560 (forward 5′-TGA TGC CCA CAA AGA CAC T-3′, reverse 5′-CCG AGT AAG TCC CAG ACG AT-3′), and RUNX−195 (forward 5′-ACG GTA GCC CTC AAA TCT CC-3′, reverse 5′-GAT GGT GCG TGG ACA GAG TA-3′)]. After 25- to 30-cycle amplification, PCR products were run on a 2% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized under UV light.

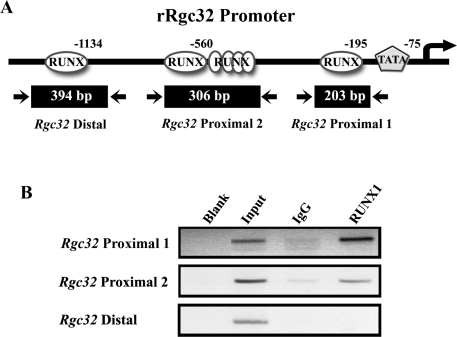

Figure 8.

Evidence of RUNX1 binding in the Rgc32 promoter region in vivo. A, Schematic map of the rat Rgc32 promoter region. The locations of primers used to amplify DNA fragments spanning RUNX transcription binding sites were designated in the rat Rgc32 promoter region. B, ChIP detection of RUNX1 transcription factor binding to the rat Rgc32 promoter region in luteinizing granulosa cells. ChIP assays were performed using DNA extracted from granulosa cells obtained at 10 h after hCG injection. One tenth of the chromatin was kept as input DNA control (Input) before immunoprecipitation. Immunoprecipitations were performed with RUNX1 antibody, or normal rabbit IgG served as a negative control. DNAs were analyzed by PCR using primers indicated previously. RUNX−195 (203 bp) and RUNX−560 (304 bp) DNA fragments containing RUNX1 transcription factor binding sites were enriched in chromatin samples immunoprecipitated with RUNX1 antibody as well as input DNA. Experiments were repeated at least five times, each with different granulosa cell samples.

Cloning of the rat Rgc32 promoter and generation of Rgc32 promoter-reporter plasmid constructs

Rat genomic DNA was isolated from tail samples of rats using an Easy-DNA kit (Invitrogen Life Technologies). A 1317-bp (−1226/+91) fragment and 871-bp (−780/+91) fragment of the Rgc32 gene (GenBank accession no. NW_001084709) were amplified using the primers attached with restriction enzyme sites (MluI and NcoI) and cloned into the pCRII-TOPO Vector (Invitrogen Life Technologies) as described previously (19). Cloned fragments were digested with MluI and NcoI enzyme, and subcloned into a multiple cloning site of the pGL3 basic vector (Promega, Madison, WI). Site-directed deletion mutations of the Rgc32 promoter were generated using a QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Stratagene). The sequences of the oligonucleotide primers used to generate respective Rgc32 promoters and desired deletions or mutations in the Rgc32 promoter are listed in supplemental Table 1, which is published as supplemental data on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://endo.endojournals.org. All constructs cloned into the expression vector were sequenced commercially to verify their authenticity (MWG Biotech, Inc., High Point, NC).

Transient transfection and luciferase reporter assay

Granulosa cells were isolated from immature rats (48 h after PMSG) as described previously. The cells were plated on 12-well plates at approximately 3–5 × 105 cells per well in Opti-MEM (Life Technologies, Inc.) media. Three hours after plating, the cells were transfected with respective firefly luciferase reporter plasmids (pGL3-basic vector or pGL3-Rgc32 promoter constructs, 1 μg/well) and Renilla luciferase vector (pRL-TK vector, 0.1 μg/well) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen Life Technologies). Fresh medium (Opti-MEM + 1× insulin, transferrin, and selenium + 1% gentamycin + 0.01% sodium pyruvate) was added 4 h after transfection. On the next day, cells were washed with fresh media and cultured in the absence or presence of forskolin (FSK) (10 μm), phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (20 nm), or FSK plus PMA. The cells were harvested 12 h after the treatment by adding 250 μl lysis buffer (Promega) directly to the plate. Firefly and Renilla luciferase activity in the extracts was measured using a Dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega), and each reaction was monitored for 10 sec by a sequential auto-injection luminometer (Berthold Technologies, Bad Wildbad, Germany). Firefly luciferase activities were normalized by Renilla luciferase activities, and each experiment was performed in triplicate at least three times.

Statistical analyses

Results were expressed as mean ± sem. All data were analyzed by ANOVA (one-way ANOVA or two-way ANOVA for luciferase activity assays) to determine the significant difference among groups. If ANOVA revealed significant effects of time of tissue collection, time of culture, or treatment, the means were compared by Tukey test, with P < 0.05 considered significant.

Results

Rgc32 expression during the periovulatory period

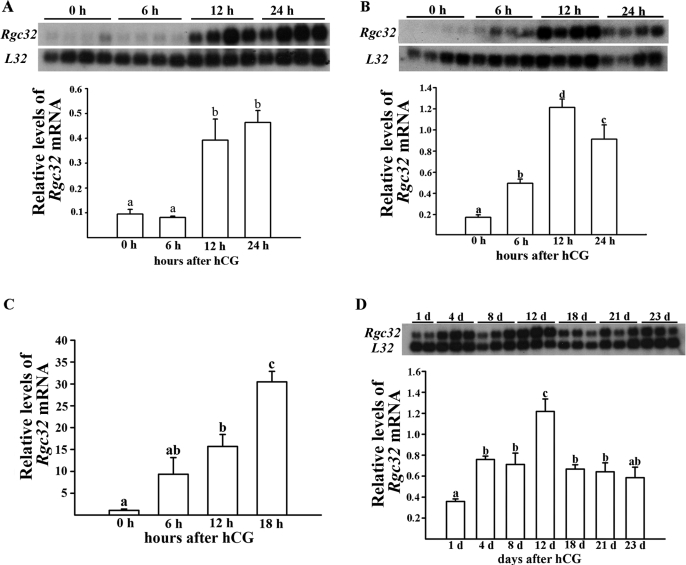

In the present study, we sought to first determine whether Rgc32 mRNA was expressed in a spatial/temporal-specific manner in the ovary. Northern blot analyses revealed a single transcript (∼1 kb) of the Rgc32 gene in total RNA isolated from ovaries of gonadotropin-stimulated immature rats obtained at selected time points after hCG injection during the periovulatory period (Fig. 1A) and the luteal period (Fig. 1D). During the hCG-induced periovulatory period, Rgc32 mRNA levels were significantly increased around the time of ovulation (12 h after hCG, 4-fold higher than levels at 0 h after hCG) and persisted through postovulatory luteinization (Fig. 1A). We also examined the expression pattern of Rgc32 mRNA in mouse ovaries during the same periovulatory period. Northern blot analyses demonstrated the up-regulation of Rgc32 mRNA after hCG injection, and the level was highest at 12 h after hCG (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Profile of Rgc32 expression in gonadotropin-stimulated rodent ovaries during the periovulatory and luteal period. Induction of Rgc32 expression during the hCG-induced periovulatory period in rat ovaries (A), mouse ovaries (B), rat COCs (C), and during the hCG-induced luteal period in rat ovaries (D). A, B, and D, Autoradiograph of a representative Northern blot analysis shows Rgc32 mRNA and ribosomal protein L32 mRNA in gonadotropin-stimulated rodent ovaries collected before or at selected hours and days after hCG injection. Relative levels of Rgc32 mRNA were normalized to the L32 band in each sample (mean ± sem; n = 3–4 independent animals). C, The levels of Rgc32 mRNA in COCs were measured using a real-time PCR as described in Materials and Methods. Bars with no common superscripts are significantly different (P < 0.05).

Next, we determined the expression profile of Rgc32 gene in COCs during the periovulatory period. The increase in levels of Rgc32 mRNA was detected at 12 and 18 h after hCG (15- and 30-fold, respectively) compared with that of 0 h (Fig. 1C).

Rgc32 expression during the luteal period

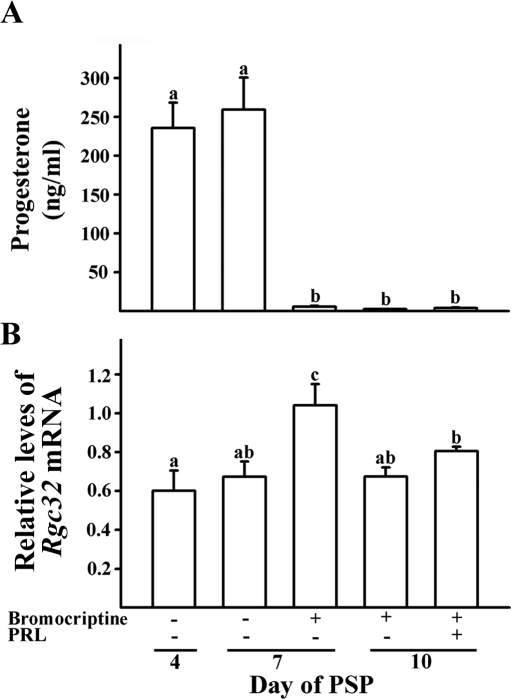

In ovaries obtained from gonadotropin-induced pseudopregnant rats, Rgc32 mRNA was readily detectable throughout the luteal period (Fig. 1D). Interestingly, a transient increase in levels of Rgc32 mRNA was detected at d 12 after hCG. This time point roughly coincides with the rapid decline of serum progesterone levels in this animal model (12). To determine further whether functional regression of the CL is related to the transient increase in Rgc32 mRNA levels observed in pseudopregnant rats, we used the induced-functional and subsequent structural luteolysis rat model. Functional regression and structural luteolysis by PRL ablation-replacement treatment were confirmed by depletion of serum progesterone (Fig. 2A) and a decrease in ovarian weights in treated animals (data not shown). The decrease in these parameters were comparable to those previously reported (21). In vehicle-treated animals (PSP4 and 7), levels of Rgc32 mRNA were not statistically different from ovaries of gonadotropin-induced pseudopregnant rats. However, Rgc32 mRNA levels were transiently increased (∼1.8-fold; P < 0.01) in ovaries exposed to bromocriptine, which blocked the endogenous PRL release, thus inducing functional regression as evidenced by a sharp decline of serum progesterone levels (Fig. 2, A and B).

Figure 2.

Serum progesterone (A) and Rgc32 mRNA levels (B) in the PRL ablation-replacement model of induced luteal regression. Group treatments are indicated across the abscissa; ovaries collected on PSP4 were fully functional, ovaries collected on PSP7 were functionally normal or functionally regressed (without or with bromocriptine treatment, respectively), and ovaries collected on PSP10 were functionally regressed (bromocriptine without PRL replacement) or functionally and structurally regressed (bromocriptine with PRL replacement). The levels of progesterone concentrations were measured in serum obtained from each animal (mean ± sem; n = 5 animals per time point). Relative levels of mRNA for Rgc32 were normalized to the L32 band in each sample (mean ± sem; n = 5 independent animals). Bars with no common superscripts are significantly different (P < 0.05).

Rgc32 expression in naturally cycling rats during the periovulatory period

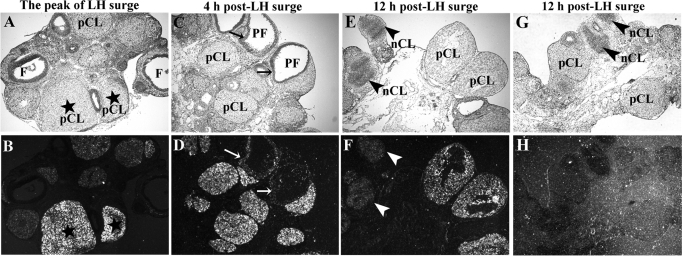

To confirm further that the up-regulation of Rgc32 mRNA levels observed in periovulatory ovaries of gonadotropin-stimulated immature rats also occurs during the natural periovulatory period, we evaluated the expression of Rgc32 in ovaries collected during the period of the endogenous gonadotropin surge and ovulation in normally cycling adult rats. Results of in situ hybridization analysis demonstrated corresponding expression patterns of Rgc32 between gonadotropin-stimulated immature and naturally cycling adult rat models. For instance, in ovaries obtained at the peak of the LH surge, hybridization signals for Rgc32 mRNA were barely detectable in growing and preovulatory follicles, yet the expression of Rgc32 mRNA was apparent in the majority of CL from previous estrous cycles (Fig. 3, A and B). After the LH surge, periovulatory follicles began to express Rgc32 mRNA in both granulosa and theca cell layers (Fig. 3, C and D), and Rgc32 mRNA continued to localize to newly forming CL (Fig. 3, E and F). Newly forming CL were easily distinguished from aging CL due to the presence of luteinizing granulosa cells inside the forming CL structure. Interestingly, the intensity of the hybridization signal in the newly forming CL was lower compared with the adjacent CL that was formed during previous estrous cycles.

Figure 3.

In situ hybridization analysis of Rgc32 mRNA during the periovulatory period in ovaries obtained from naturally cycling rats. Representative bright-field (A, C, E, and G) and corresponding dark-field (B, D, F, and H) photomicrographs are depicted. Ovaries were collected at 0 (at the peak of the LH surge), 4, and 12 h after the LH surge. Panels G and H were hybridized with sense probes (negative control). Arrows in D indicate periovulatory follicles (F) expressing Rgc32 mRNA. Arrowheads in F indicate newly forming CL (nCL). Asterisks in B indicate CL generated during previous estrous cycles. Original magnification of all slides is ×40. pCL, Corpus luteum from previous cycles; PF, preovulatory follicle.

Effects of hCG on the expression of Rgc32 in granulosa cell cultures

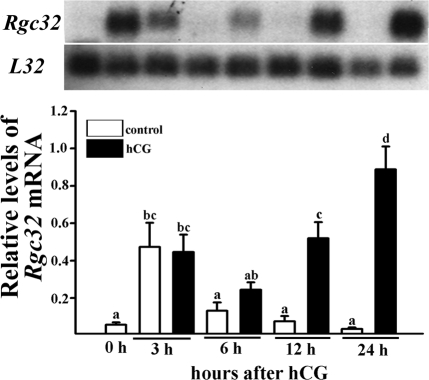

The finding that Rgc32 expression was induced in preovulatory follicles after the LH surge prompted us to investigate the regulatory mechanism(s) involved in the expression of Rgc32 using an in vitro model. At first, the regulation of Rgc32 mRNA by LH was assessed via culturing granulosa cells in the absence and presence of hCG (1 IU/ml) for selected time periods. As expected, Rgc32 mRNA was barely detectable in granulosa cells isolated at 48 h after PMSG (0 h; Fig. 4). However, hCG treatment stimulated Rgc32 expression in granulosa cell cultures. The levels of Rgc32 mRNA were highest at 24 h after culture, similar to our findings in intact ovaries (Fig. 1A).

Figure 4.

Stimulation of Rgc32 expression by hCG in rat granulosa cells in vitro. Autoradiograph of a representative Northern blot analysis shows Rgc32 mRNA and ribosomal protein L32 mRNA in granulosa cells obtained from rat preovulatory ovaries (48 h after PMSG) and cultured in medium alone (control), or with hCG (1 IU/ml) for 0, 3, 6, 12, or 24 h. Relative levels of Rgc32 mRNA were normalized to the L32 band in each sample (mean ± sem; n = 4 independent culture experiments). Bars with no common superscripts are significantly different (P < 0.05).

Interestingly, an acute, yet transient elevation of Rgc32 mRNA levels was observed in the cells cultured for 3 h. Because this elevation of Rgc32 mRNA was observed both in control (defined medium alone) and hCG-treated cells at the same degree, it did not appear to be related to the hormonal treatment. Furthermore, in control cells the elevated levels of Rgc32 mRNA declined to the basal level by 6 h in culture, whereas the cells treated with hCG further accumulated Rgc32 mRNA over the culture period (Fig. 4). We also measured the levels of Rgc32 mRNA in ovaries of PMSG-primed immature rats obtained at 3 h after hCG injection using real-time PCR and found no significant difference compared with that of 0-h hCG (data not shown). These preliminary data suggested that the acute, transient increase in levels of Rgc32 mRNA in vitro might be the cell’s response to the stress associated with their removal from in vivo conditions.

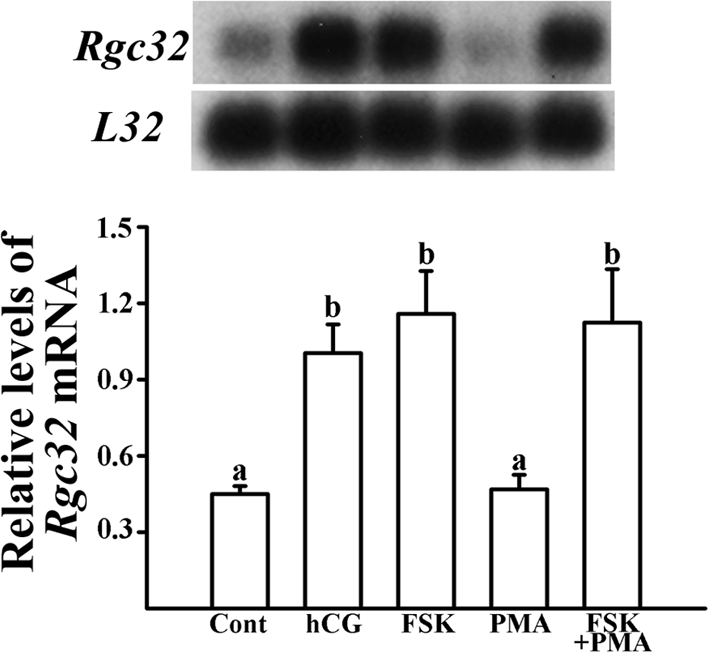

Next, to determine which signaling pathway(s) is involved in the up-regulation of Rgc32 mRNA in response to hCG stimulation, granulosa cells were cultured with an activator of adenylate cyclase, FSK, or an activator of protein kinase C (PKC, PMA, for 24 h. The LH surge is known to activate both protein kinase A (PKA) and PKC signaling pathways in preovulatory granulosa cells (22). Treatment with FSK, not PMA, stimulated Rgc32 expression (P < 0.01) at the level that mimicked the stimulatory effect by hCG (Fig. 5). This result demonstrated that the up-regulation of Rgc32 mRNA by hCG is mediated through the activation of the PKA signaling pathway.

Figure 5.

Regulation of Rgc32 expression by activators of intracellular signaling pathways in granulosa cells in vitro. Autoradiograph of a representative Northern blot analysis shows Rgc32 mRNA and ribosomal protein L32 in granulosa cells from rat preovulatory ovaries (48 h after PMSG) cultured in medium alone (Cont), or with hCG (1 IU/ml), FSK (10 μm), PMA (20 nm), or FSK plus PMA for 24 h. Relative levels of Rgc32 mRNA were normalized to the L32 band in each sample (mean ± sem; n = 4 independent culture experiments). Bars with no common superscripts are significantly different (P < 0.05).

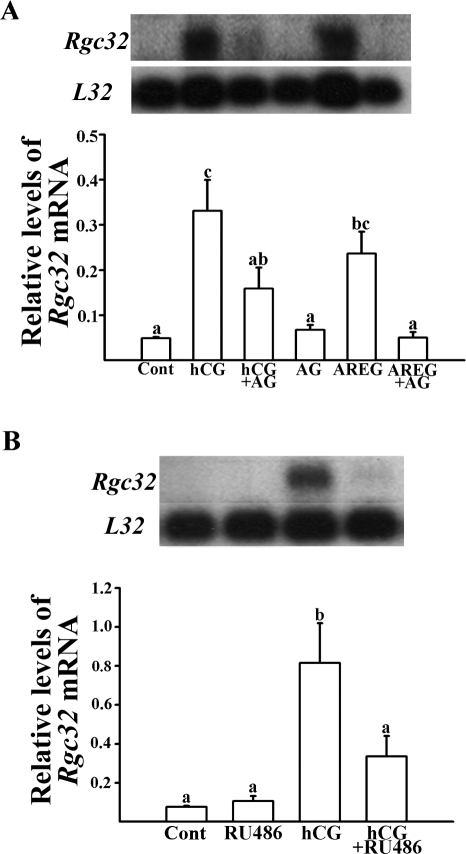

Hormonal regulation of Rgc32 mRNA expression in cultured granulosa cells

Next, we tested whether the up-regulation of Rgc32 mRNA is mediated by the LH-induced activation of progesterone receptor (PGR) and/or epidermal growth factor (EGF) signaling pathways. As shown in Fig. 6A, the stimulatory effect of hCG on Rgc32 mRNA accumulation is reduced by cotreating cells with AG1478 (AG), a specific inhibitor of EGF-receptor tyrosine kinase. In contrast, amphiregulin (AREG), one of the EGF-related peptides produced by periovulatory granulosa cells in response to the LH surge, increased the levels of Rgc32 mRNA in the culture. This AREG-induced accumulation of Rgc32 mRNA was completely blocked by AG, confirming that the effect of AREG on Rgc32 mRNA is mediated through the activation of EGF receptors (Fig. 6A). Next, to determine the regulation of Rgc32 mRNA by the activation of PGR, we treated granulosa cells with RU486, an antagonist for PGR. We found that the hCG-induced Rgc32 mRNA is abolished by RU486, indicating that the activation of LH-induced PGR is involved in Rgc32 mRNA expression. Preliminary experiments with ZK98299 (n = 2), a specific PGR antagonist, in the place of RU486, showed similar results (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Hormonal regulation of hCG-induced Rgc32 expression in cultured rat granulosa cells. A, Inhibition of Rgc32 expression by AG (EGF receptor tyrosine kinase-selective inhibitor, 1 μm). The cells were cultured in medium alone (Cont), hCG (1 IU/ml), AG, AREG (EGF-related peptide, 100 nm/ml), hCG plus AG, or AREG plus AG for 24 h. B, Inhibition of Rgc32 expression by RU486. Granulosa cells were cultured in medium alone (Cont), hCG (1 IU/ml), RU486 (PGR antagonist, 10 μm), or hCG plus RU486 for 24 h. Autoradiograph of a representative Northern blot analysis shows Rgc32 mRNA and ribosomal protein L32 mRNA in granulosa cells from rat preovulatory ovaries (48 h after PMSG). Relative levels of Rgc32 mRNA were normalized to the L32 band in each sample (mean ± sem; n = 6 independent culture experiments). Bars with no common superscripts are significantly different (P < 0.05).

Regulation of Rgc32 expression by RUNX1 in cultured granulosa cells

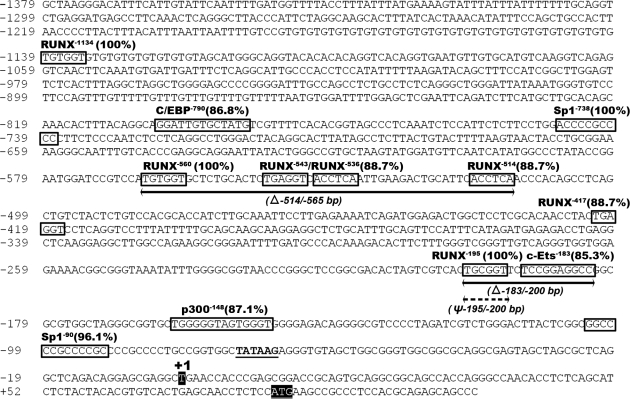

To determine whether RUNX1 directly regulates Rgc32 expression, we first analyzed the putative promoter region [∼1.5-kb upstream of transcription start site (TSS)] of the rat Rgc32 gene using a web-based transcription factor prediction program (TFSEARCH version 1.3 using TRNASFAC database, with a threshold cutoff of 0.85; http://www.cbrc.jp/research/db/TFSEARCH.html). The analysis revealed the presence of several putative RUNX binding sites, with three consensus binding sites (Fig. 7), as well as binding sites for coregulatory proteins that are known to interact with RUNX, such as p300, Ets, CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein, and specificity protein (SP) 1. These findings implicate the possibility of transcriptional regulation on the Rgc32 gene by RUNX1 in periovulatory granulosa cells. To examine whether RUNX1 specifically binds to these candidate sites in the Rgc32 promoter in vivo, ChIP assays were performed using periovulatory granulosa cells isolated from gonadotropin-treated immature rats (10 h after hCG), a time period of maximal RUNX1 protein (4) and high expression of Rgc32 gene (Fig. 1A). PCR fragments [306 bp (−780/−475) and 203 bp (−307/−105)] containing the RUNX binding sequence [RUNX−195 (TGTGGT) and RUNX−560 (TGCGGT), respectively] in the proximal promoter region were enriched in chromatin samples treated with RUNX1 antibody compared with normal rabbit IgG, demonstrating the in vivo binding of RUNX1 on the proximal Rgc32 promoter (RUNX−195 and RUNX−560; Fig. 8B), whereas no PCR fragment was amplified in the further upstream region (RUNX−1134; Fig. 8, A and B).

Figure 7.

Nucleotide sequences of rat Rgc32 promoter regions. The rat Rgc32 promoter sequence was analyzed using a genomic library. Nucleotide sequences are numbered from TSS at +1. Putative transcription factor binding sites (boxed sequence) are predicted by TFSEARCH. TATA box is underlined. Translation initiation site is the black shaded box (ATG).

Next, to determine the molecular mechanism(s) by which the ovulatory LH stimulates the transcriptional activation of the Rgc32 gene, two rat Rgc32 promoter fragments (−1226/+91 and −780/ +91 bp) were cloned upstream of a firefly luciferase reporter gene and transfected to preovulatory granulosa cells isolated from ovaries obtained at 48 h after PMSG injection (Fig. 9A). The cells were cultured overnight before stimulating with FSK (10 μm), PMA (20 nm), or FSK plus PMA, two signaling activators that have been used to mimic the action of an ovulatory dose of LH on preovulatory granulosa cells (23). FSK treatment increased the luciferase activities of −1226/+91 and −780/+91 bp reporter constructs (2.6-fold for both constructs) compared with that of control cultures (Fig. 9A), whereas PMA had no significant effect. However, when FSK and PMA were cotreated, the luciferase activity increased 5- to 6-fold, respectively, over the control, demonstrating an additive effect of PMA on the FSK-induced Rgc32 promoter activity. Of note, the transcriptional activity of the −780/+91 bp construct containing the proximal promoter region was higher than that of the longer construct (−1226/+91), suggesting that the upstream region of 446 bp (−1226/−781) inhibited the activity of the Rgc32 promoter. To determine further whether the Rgc32 promoter activity is affected by RUNX binding sites in the promoter sequence, we generated the Rgc32 promoter (−780/+91 bp) constructs containing deletions in RUNX binding sites (Δ−514/−565 bp and Δ−514/-565 bp + Δ−183/−200 bp) and mutation in the proximal RUNX binding site (ψ−195/−200 bp). The FSK and FSK plus PMA-stimulated transactivation of the Rgc32 promoter was reduced in a mutant construct (Δ514/−565 bp) containing a deletion of four RUNX binding sites (one consensus sequence and three potential binding sites with 89% homology) (Fig. 9B). Mutation in the RUNX binding site at ψ−195/−200 bp also reduced the Rgc32 promoter activity stimulated by agonists. However, the deletion of both regions of RUNX binding sites (Δ−514/−565 bp + Δ−183/−200 bp) had no additive effect on the FSK as well as FSK plus PMA-induced activation of the Rgc32 promoter construct.

Figure 9.

Regulation of the Rgc32 promoter in luteinizing granulosa cells. A, Stimulation of Rgc32 promoter activity by FSK and FSK plus PMA. Rat granulosa cells isolated from gonadotropin-primed immature rats (48 h after PMSG) were transiently transfected with empty, −1226/+91 bp, or −780/+91 bp Rgc32-luciferase reporter constructs, stimulated with FSK, PMA, or FSK plus PMA and cultured for 12 h. B, RUNX binding sites contribute to the transactivation of the Rgc32 promoter. The granulosa cells were transiently transfected with the Rgc32 promoter (−780/+91 bp) constructs containing deletions in RUNX binding sites (Δ−514/−565 bp and Δ−514/−565 bp + Δ−183/−200 bp) or mutation in the RUNX binding site (ψ−195/−200 bp). Black boxes represent the consensus RUNX binding site. Shadowed boxes represent the putative RUNX binding site (89% match). Firefly luciferase activities were normalized by Renilla luciferase activities, and each experiment was performed in triplicate at least three times. A significant effect of interaction between treatments and constructs was observed. Bars with no common superscripts in each panel and among vector constructs are significantly different (P < 0.05).

Discussion

During follicular growth a precise balance between proliferation and differentiation of follicular cells is maintained by coordinated actions of multiple hormones, such as estradiol, FSH, LH, and growth factors (24,25). However, after the LH/FSH surge, this balance is tilted toward differentiation, which is a prerequisite step for a periovulatory follicle to transform into a CL (reviewed in Refs. 1 and 3). This shift in the balance has been recognized as a result of the rapid switch in the expression profile of genes, including cell cycle modulators (2,3,26,27,28). In the present study, we documented the induction of Rgc32 expression by the LH surge in periovulatory follicles and in the CL. In previous functional studies, RGC32 has played a role in regulating the cell cycle either as an activator or repressor in a cell type-specific manner (8,9). Given that luteinizing granulosa cells and luteal cells cease to proliferate and arrest in the cell cycle, we speculated that RGC32 might function as a suppressor of the cell cycle in ovarian cells. In addition, a recent study showed that RGC32 regulated transcription of genes during smooth muscle cell differentiation (10). Therefore, whether RGC32 plays a role in the cell cycle or gene regulation in luteinizing granulosa /luteal cells needs to be determined further.

Using the primary granulosa cell culture system, we demonstrated that an ovulatory LH stimulus is an initial trigger of Rgc32 expression. This LH-induced up-regulation of Rgc32 mRNA in preovulatory granulosa cells was mediated through activation of the PKA signaling pathway, but not the PKC pathway. This result is also in agreement with the data from the Rgc32 promoter assay showing that FSK stimulated the activity of Rgc32 promoter-luciferase reporter constructs, yet PMA had no effect. Interestingly, we observed an additive effect of PMA treatment on FSK in the promoter-reporter activity, but not in endogenous Rgc32 expression. One possibility is that endogenous Rgc32 expression was mediated by the collective activity of the full-length promoter, whereas the promoter-reporter activity was limited by the partial promoter region tested.

The present study demonstrated that activation of both PGR and EGF signaling pathways, two key mediators of ovulatory LH action, are involved in the up-regulation of Rgc32 expression in luteinizing granulosa cells. Interestingly, the induction of Runx1 expression by LH was also dependent on the activation of PGR as well as EGF signaling in periovulatory granulosa cells (4). Considering that Rgc32 mRNA levels were reduced by Runx1 knockdown (4), it is conceivable that the involvement of PGR and EGF signaling pathways on Rgc32 expression is mediated, at least in part, through RUNX1. However, it is also possible that the expression of Rgc32 is directly regulated by PGR, although no consensus PGR response element was found in the Rgc32 promoter analyzed. For instance, it was shown that PGR regulated the target gene expression by interacting with SP1 transcription factor (29,30). In addition, Doyle et al. (23) showed that PGRA expression in luteinizing rat granulosa cells enhanced Adamts1 promoter activity via SP1/SP3 binding sites and C/EBPβ. Our analysis of the Rgc32 promoter also revealed two SP1/SP3 binding sites and a C/EBPβ binding site within 1.5-kb upstream of the TSS, suggesting the potential regulation of this gene by PGR through these transcription factors.

In an attempt to identify intracellular mediators that regulate the expression of the Rgc32 gene, we first examined the putative promoter region of the Rgc32 gene. Of note was the region that contains many possible transcription factor binding sites, including SP1/SP3, C/EBPβ, p300, and activator protein 1. In particular, three consensus and four possible binding sites (89% identity each) for RUNX transcription factors were identified within 1.5-kb upstream of the TSS. Further comparison between mouse and rat promoter regions revealed high similarity in RUNX binding sites (data not shown), suggesting the conserved regulatory mechanism of Rgc32 expression by RUNX transcription factors between these two species. The expression of Runx1 was induced in both mouse and rat periovulatory ovaries (4,31) in a temporal and spatial-specific manner similar to our present findings of the Rgc32 expression pattern, supporting the hypothesis that RUNX1 may be involved in Rgc32 expression during the periovulatory period. These observations prompted us to investigate potential interactions between RUNX1 and the Rgc32 promoter in luteinizing granulosa cells of periovulatory follicles. Indeed, data from ChIP analyses demonstrated that RUNX1 interacted with two different Rgc32 promoter regions. Furthermore, we found that the deletion or mutation of putative RUNX binding sites in the promoter region decreased the agonist-induced luciferase activity. Together, these findings suggest that the Rgc32 gene may be a direct transcriptional target of RUNX1 in periovulatory granulosa cells.

One of the important findings was the high expression of Rgc32 in luteal cells. We also observed noticeable differences in the signal intensity of Rgc32 mRNA between the newly forming CL and CL generated from previous estrous cycles. Studies using the induced-functional and subsequent structural luteolysis model, as well as the gonadotropin-induced pseudopregnant model, indicated that the transient accumulation of Rgc32 mRNA during functional regression might account for this difference in the signal intensity. Whether there is any causal relationship between the inducers of functional regression, such as prostaglandin F2α and LH (reviewed in Ref. 3), and the transient up-regulation of Rgc32 expression needs to be determined further. As for transcriptional regulators of Rgc32 in luteal cells, the involvement of RUNX1 is unlikely because RUNX1 expression is decreased after ovulation (4). However, other members of the RUNX transcription factor family may play a role in the luteal expression of Rgc32 because these transcription factors recognize the same binding site in the promoter. For example, in situ hybridization and real-time PCR data (32) showed high expression of RUNX2 transcription factor in the CL of rat ovaries. In fact, the expression pattern of Runx2 was similar to that of Rgc32 in LH-stimulated luteinized cells (results are in the supplemental data and Fig. 5), suggesting the possible regulation of Rgc32 expression by RUNX2. Besides RUNX2, another potential regulator of Rgc32 is the tumor suppressor TP53, which was identified as a direct transcriptional regulator of the Rgc32 gene in glioma cells (9). When we compared the levels of Rgc32 mRNA and TP53 mRNA among three different ovarian cancer cell lines and human granulosa cells (the comparisons are shown in the supplemental data), the expression pattern of these two genes was remarkably similar. In contrast, the potential regulation of Rgc32 by TP53 is doubtful in rat luteal cells. For example, Trott et al. (20) documented the constitutive expression of TP53 in CL from d 8–14 gonadotropin-induced pseudopregnant rat ovaries, whereas the levels of TP53 protein gradually decreased in the CL isolated from d 8–12 and became undetectable on d 14. We also found constitutive expression of TP53 in the induced functional and subsequent structural luteolysis model (real-time PCR data, data not shown), indicating the lack of correlation between TP53 and RGC32 expression in luteal cells of the rat ovary. These observations may reflect the species- and cell type-specific regulation of Rgc32 expression by TP53.

In summary, this study is the first report characterizing the temporally regulated and spatial-specific expression pattern of the Rgc32 gene in the ovary. The LH-induced expression of Rgc32 was mediated through the activation of PGR and EGF signaling pathways. The present study also identified RUNX1 as one of the transcriptional regulators involved in Rgc32 expression. Further studies will be needed to identify the function of RGC32 in ovarian cells, and, therefore, to determine the physiological importance of Rgc32 expression in periovulatory granulosa cells and luteal cells in the ovary.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Michael Kilgore for helpful consultation on luciferase-reporter constructs, Dr. Feixue Li for technical help with ovarian cancer cell lines, and Drs. Phillip Bridges, Carolyn Komar, Feixue Li, and Rajagopal Sriperumbudur for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants NCRR P20 RR 15592 (to T.E.C. and M.J.) and RO3 HD051727-01 (to M.J.).

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online February 28, 2008

Abbreviations: AG, AG1478; AREG, amphiregulin; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; CL, corpora lutea; COC, cumulus oocyte complex; DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide; EGF, epidermal growth factor; EtOH, ethyl alcohol; FBS, fetal bovine serum; FSK, forskolin; hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; PGR, progesterone receptor; PKA, protein kinase A; PKC, protein kinase C; PMA, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate; PMSG, pregnant mare serum gonadotropin; PRL, prolactin; PSP, pseudopregnancy; PSP4, d-4 pseudopregnancy; PSP7, d-7 pseudopregnancy; PSP10, d-10 pseudopregnancy; Rgc32, response gene to complement 32; SP, specificity protein; TSS, transcription start site.

References

- Murphy BD 2000 Models of luteinization. Biol Reprod 63:2–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robker RL, Richards JS 1998 Hormonal control of the cell cycle in ovarian cells: proliferation versus differentiation. Biol Reprod 59:476–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocco C, Telleria C, Gibori G 2007 The molecular control of corpus luteum formation, function, and regression. Endocr Rev 28:117–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo M, Curry Jr TE 2006 Luteinizing hormone-induced RUNX1 regulates the expression of genes in granulosa cells of rat periovulatory follicles. Mol Endocrinol 20:2156–2172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffman JA 2003 Runx transcription factors and the developmental balance between cell proliferation and differentiation. Cell Biol Int 27:315–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada M, Hernandez-Gonzalez I, Gonzalez-Robayna I, Richards JS 2006 Paracrine and autocrine regulation of epidermal growth factor-like factors in cumulus oocyte complexes and granulosa cells: key roles for prostaglandin synthase 2 and progesterone receptor. Mol Endocrinol 20:1352–1365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badea TC, Niculescu FI, Soane L, Shin ML, Rus H 1998 Molecular cloning and characterization of RGC-32, a novel gene induced by complement activation in oligodendrocytes. J Biol Chem 273:26977–26981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badea T, Niculescu F, Soane L, Fosbrink M, Sorana H, Rus V, Shin ML, Rus H 2002 RGC-32 increases p34CDC2 kinase activity and entry of aortic smooth muscle cells into S-phase. J Biol Chem 277:502–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saigusa K, Imoto I, Tanikawa C, Aoyagi M, Ohno K, Nakamura Y, Inazawa J 2007 RGC32, a novel p53-inducible gene, is located on centrosomes during mitosis and results in G2/M arrest. Oncogene 26:1110–1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Luo Z, Huang W, Lu Q, Wilcox CS, Jose PA, Chen S 2007 Response gene to complement 32, a novel regulator for transforming growth factor-β-induced smooth muscle differentiation of neural crest cells. J Biol Chem 282:10133–10137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying SY, Meyer RK 1972 Ovulation induced by PMS and HCG in hypophysectomized immature rats. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 139:1231–1233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahav M, Davis JS, Rennert H 1989 Mechanism of the luteolytic action of prostaglandin F-2 α in the rat. J Reprod Fertil Suppl 37:233–240 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nothnick WB, Keeble SC, Curry Jr TE 1996 Collagenase, gelatinase, and proteoglycanase messenger ribonucleic acid expression and activity during luteal development, maintenance, and regression in the pseudopregnant rat ovary. Biol Reprod 54:616–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo T, Aten RF, Wang F, Behrman HR 1993 Coordinate induction and activation of metalloproteinase and ascorbate depletion in structural luteolysis. Endocrinology 133:690–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurusu S, Sakaguchi S, Kawaminami M, Hashimoto I 2001 Sustained activity of luteal cytosolic phospholipase A2 during luteolysis in pseudopregnant rats: its possible implication in tissue involution. Endocrine 14:337–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann JS, Kindy MS, Edwards DR, Curry Jr TE 1991 Hormonal regulation of matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors in rat granulosa cells and ovaries. Endocrinology 128:1825–1832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD 2001 Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Δ Δ C(T)) method. Methods 25:402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry Jr TE, Song L, Wheeler SE 2001 Cellular localization of gelatinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases during follicular growth, ovulation, and early luteal formation in the rat. Biol Reprod 65:855–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo M, Gieske MC, Payne CE, Wheeler-Price SE, Gieske JB, Ignatius IV, Curry Jr TE, Ko C 2004 Development and application of a rat ovarian gene expression database. Endocrinology [Erratum (2006) 147:256] 145:5384–5396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trott EA, Plouffe Jr L, Hansen K, McDonough PG, George P, Khan I 1997 The role of p53 tumor suppressor gene and bcl-2 protooncogene in rat corpus luteum death. Am J Obstet Gynecol 177:327–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedts AM, Curry Jr TE 2005 Expression of basigin, an inducer of matrix metalloproteinases, in the rat ovary. Biol Reprod 73:80–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JK, Richards JS 1995 Luteinizing hormone induces prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase-2 and luteinization in vitro by A-kinase and C-kinase pathways. Endocrinology 136:1549–1558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle KM, Russell DL, Sriraman V, Richards JS 2004 Coordinate transcription of the ADAMTS-1 gene by luteinizing hormone and progesterone receptor. Mol Endocrinol 18:2463–2478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monniaux D, Pisselet C 1992 Control of proliferation and differentiation of ovine granulosa cells by insulin-like growth factor-I and follicle-stimulating hormone in vitro. Biol Reprod 46:109–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillier SG 2001 Gonadotropic control of ovarian follicular growth and development. Mol Cell Endocrinol 179:39–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robker RL, Richards JS 1998 Hormone-induced proliferation and differentiation of granulosa cells: a coordinated balance of the cell cycle regulators cyclin D2 and p27Kip1. Mol Endocrinol 12:924–940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirk SM, Cowan RG, Harman RM 2004 Progesterone receptor and the cell cycle modulate apoptosis in granulosa cells. Endocrinology 145:5033–5043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon JD, Cherian-Shaw M, Chaffin CL 2005 Proliferation of rat granulosa cells during the periovulatory interval. Endocrinology 146:414–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang M, Mazella J, Gao J, Tseng L 2002 Progesterone receptor activates its promoter activity in human endometrial stromal cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol 192:45–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen GI, Richer JK, Tung L, Takimoto G, Horwitz KB 1998 Progesterone regulates transcription of the p21(WAF1) cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor gene through Sp1 and CBP/p300. J Biol Chem 273:10696–10701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Gonzalez I, Gonzalez-Robayna I, Shimada M, Wayne CM, Ochsner SA, White L, Richards JS 2006 Gene expression profiles of cumulus cell oocyte complexes during ovulation reveal cumulus cells express neuronal and immune-related genes: does this expand their role in the ovulation process? Mol Endocrinol 20:1300–1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S, Park E, Jo M 2007 The expression pattern of core binding factor (CBF) in the rodent ovary. Biol Reprod special issue no. 95:97 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.