Abstract

Lactoferrin is an 80-KDa iron-binding protein present at high concentrations in milk and in the granules of neutrophils. It possesses multiple activities, including anti-bacterial, anti-viral, anti-fungal, and even anti-tumor effects. Most of its antimicrobial effects are due to direct interaction with pathogens, but a few reports show that it has direct interactions with cells of the immune system. Here we show the ability of recombinant human lactoferrin (Talactoferrin-alpha, TLF) to chemoattract monocytes. What is more, addition of TLF to human peripheral blood or monocyte-derived dendritic cell cultures resulted in cell maturation, as evidenced by upregulated expression of CD80, CD83, and CD86, production of proinflammatory cytokines, and increased capacity to stimulate the proliferation of allogeneic lymphocytes. When injected into mouse peritoneal cavity, lactoferrin also caused a marked recruitment of neutrophils and macrophages. Immunization of mice with ovalbumin in the presence of TLF promoted Th1-polarized antigen-specific immune responses. These results suggest that lactoferrin contributes to the activation of both the innate and adaptive immune responses by promoting the recruitment of leukocytes and activation of dendritic cells.

Keywords: Chemotaxis, dendritic cells, cell activation, tumor immunity

Introduction

Lactoferrin is a 80 KDa protein that belongs to the transferrin superfamily, which binds Fe cations with high affinity (1, 2). It is secreted in an iron-free form from many epithelial cells into most exocrine fluids, particularly milk. In humans, its concentration varies from about 1 to 7 mg/ml in milk and in colostrum, respectively (3). Lactoferrin is a major component of the secondary granules of neutrophils, which, like many granule components, is released through degranulation upon neutrophil activation (4, 5). During inflammation, lactoferrin levels of the biologic fluids increase dramatically. This is particularly noticeable in blood, where lactoferrin concentration can be as low as 0.5∼1 μg/ml under normal conditions, but increases to 200 μg/ml with systemic bacterial infection (6, 7). Recent reports indicate that lactoferrin expression in both neutrophils and epithelial cells can be induced (8, 9).

Lactoferrin is multifunctional and has a widely accepted antimicrobial effect against bacteria, viruses, fungi, and some parasites (10). One mechanism by which lactoferrin exerts it antimicrobial effect depends on its iron-binding property that enables lactoferrin to sequester iron required for bacterial growth (10, 11). Lactoferrin is also capable of binding to glycosaminoglycans (in particular to heparan sulphate) of mucosal epithelial cells, resulting in the inhibition of microbial adhesion, colonization, and subsequent development of infection at mucosal surfaces (10, 12). Furthermore, lactoferrin has direct microbicidal activity that is independent of its iron-binding property (10, 12-14).

In addition to its antimicrobial effect, it has also been reported that lactoferrin has a variety of effects on host immune system, ranging from inhibition of inflammation to promotion of both innate and adaptive immune responses (10, 15). Interestingly, recombinant human lactoferrin (talactoferrin, TLF) has recently been used as a therapeutic agent against several cancers with positive results (16, 17), including in clinical trials (18). While the anti-inflammatory activity of lactoferrin is largely due to binding and neutralization of proinflammatory molecules such as bacterial endotoxin and soluble CD14, its capacity to promote innate immune responses is often explained by the ability of lactoferrin to promote activation of neutrophils and macrophages (10, 15, 19). We hypothesized that lactoferrin might also have direct receptor-dependent activating effect on antigen- presenting cells (APCs) including dendritic cells (DCs), thereby mobilizing and alerting the adaptive immune system.

Here we show for the first time the ability of recombinant human GMP-quality lactoferrin to recruit and activate APCs, and to enhance antigen-specific immune responses. These functional characteristics of lactoferrin are also shared by alarmins, a group of endogenous mediators of the immune system that link innate and adaptive immunity by promoting the recruitment and activation of APCs (20). Therefore, lactoferrin may act as an alarmin and rapidly mount responses to danger signals.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Antibodies

FITC-conjugated anti-human CD4, CD18, CD80, CD83, CD86, PE-conjugated anti-human CD3, CD11b, CD14, CD19, CD29, CD56, Cy5.5-conjugated anti-human CD54 and PerCP-Cy5.5-conjugated anti-human HLA-DR were purchased from BD Pharmingen (Palo Alto, CA). FITC-conjugated anti-human BDCA-2 and CD1c were purchased from Miltenyi Biotech (Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). FITC -conjugated anti-mouse CD11b, LY6G (anti-Gr-1), PE-CD11c, and PerCP-B220 were purchased from BD Pharmingen. Anti-mouse F4/80 PE-Cy5 was from eBiosciences (San Diego, CA).

Human recombinant lactoferrin (Talactoferrin alfa, TLF) was a gift from Agennix Inc (Houston, TX). In brief, TLF is recombinantly produced in Aspergillus niger var. awamori (nontoxigenic and nonpathogenic)(21), purified by ion-exchange chromatography, yielding a 95-99% purity, with a 3-dimensional structure to be essentially identical to that of human lactoferrin (hLF) isolated from human milk (22). TLF is pharmaceutical-grade, manufactured using a GMP process, free of contaminating host-cell DNA, host-cell proteins or mycotoxins. Human MCP-1/CCL2, SLC/CCL21 and SDF-1α/CXCL12 were from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ).

Cell culture

Human peripheral blood enriched in mononuclear cells was obtained from healthy donors by leukapheresis (Transfusion Medicine Department, Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, with an approved human subjects agreement). The blood was centrifuged through Ficoll-Hypaque (Sigma), and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) collected at the interface were washed with PBS and centrifuged through isoosmotic Percoll (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) gradient. The enriched monocyte populations were obtained at the very top of the gradient (top fraction). For some experiments monocytes were further purified by magnet sorting (monocyte purification kit, Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA). To obtain monocyte-derived dendritic cells, monocytes were cultured as described previously (23). Briefly, cells were resuspended in RPMI containing 10% FCS (GIBCO-Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at 1×106 cells/ml in the presence of IL-4 and GM-CSF (Pepro Tech, both at 50 ng/ml) every two days. After six days, they were used as immature DCs (iDCs). To induce maturation, iDCs were cultured in the presence of LPS (E. coli; 055:B5 strain, 200 or 500ng/ml, Sigma) or distinct concentrations of TLF. CD1c+ PBDCs were purified with the CD1c+ purification kit (Miltenyi) following the vendor’s instructions. For mixed lymphocyte reaction experiments (MLR) 105 Percoll-enriched lymphocytes (105/well) were cocultured with DCs at different ratios in 96-well round-bottomed plates (COSTAR) for 5 days, with the addition of 1μCi of [3H]-TdR to each well. (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) 16 h before the end of the experiment. Cells were then harvested onto filter membranes using an Inotech harvester (Inotech Biosystems, Rockville, MD), and the amount of incorporated [3H]-TdR was measured with a Wallac Microbeta counter (PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Boston, MA).

For regulatory T lymphocytes (Treg) studies, PBMCs were cultured at 106 cell/ml in RPMI 1640 10%FBS for 48h with or without IL-2 (100 U/ml), TNF-α (50 ng/ml) or various concentrations of TLF as specified. Subsequently, cultured PBMCs were recovered, counted and stained either with the AnnexinV/PI kit to detect cell viability or with CD3, CD4 and FoxP3 (APC-anti-human FoxP3 Staining Set, eBiosciences) for Treg determination.

Analysis of cell viability

Cells were recovered after the desired period of time from the plate and the wells rinsed with cold PBS/EDTA 5mM. Adherent cells were recovered by gently scraping the wells. After mixing well the recovered volumes, a fraction of the recovered cells were used for counting and the rest were stained with the Annexin V/PI staining set (from eBiosciences) to assess early and late apoptosis by flow cytometry. Cells that didn’t stained for Annexin V and PI were considered alive; cells that only stained for Annexin V (early apoptosis) were considered “dying”; cells that were double positive (DP) or were missing after counting the recovered cells were included in the “dead” category.

Migration assays

Migration assays were performed using two different approaches to double check the effect of lactoferrin: 1) 48-well micro-chemotaxis chambers (NeuroProbe, Inc.) and 2) 6.5 mm transwell polycarbonate inserts (Corning) as described previously. Membranes of 5μm pore diameter were used in both systems. Cells were washed in PBS and re-suspended in RPMI 1640 (GIBCO) supplemented with 1% BSA (Sigma). When pertussis toxin from B. pertussis (PTx; List Biological Laboratories Inc.) was used, cells were preincubated at 37°C for 1 h in the presence of the toxin at concentration of 100-200 ng/ml before migration experiments. Cells then were loaded in the chambers and allowed to migrate for 2 h at 37°C. In the 48-well chemotaxis assay, experiments were run in triplicates and migrated cells were fixed, stained and counted using Bioquant Life Science (Bioquant Image Analysis Corp, Nashville, TN) software. Transwell migration assays were performed as previously described (24) with a slight modification: experiments were run in duplicates, and migrated cells were recovered. An aliquot of the migrated cells was used for counting while the remaining cells were used to phenotype peripheral blood dendritic cells (PBDCs) within the PBMCs as previously described (25): HLA-DR+/Lin (CD3, CD11b, CD14, CD19 and CD56)neg and either BDCA-2+ or CD1c+ using a FACScan cytometer (BD). The results of migration experiments were shown as migration index, which was calculated as [number of cells migrated in the presence of a chemotactic factor]/[number of cells migrated in the absence of a chemotactic factor].

Cytokine production

Supernatants from monocytes or DCs were collected after 48h-treatment with or without TLF or LPS. Samples were read using a multiplex plate for IL-12p70, IL-6, TNF-α and IL-10 (Pierce Biotech, Woburn, MA) or a 10-plex cytokine plate (Meso Scale Discovery, Gaithersburg, MD)

Leukocyte recruitment

Female wild type C57BL/6NCr mice (8-10 weeks old) were provided by Animal Production Area of the NCI (Frederick, MD). NCI-Frederick is accredited by AAALAC International and follows the Public Health service Policy for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Animal care was provided in accordance with the procedures outlined in the “Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” (National research council; 1996; National Academy Press, Washington D.C.). Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1.0 ml of PBS containing various amounts of TLF or LPS. After 4 h or 24 h hours, mice were sacrificed and cells were harvested by peritoneal lavage using 5 mL of ice-cold PBS with EDTA 5 mM. Cells were counted, phenotyped for Gr-1/F4-80 and CD11b/CD11c/B220 and analyzed using a FACScan flow cytometer (BD).

Immunization procedure and detection of antigen-specific splenocyte proliferation and cytokine production

Eight-week old C57BL/6 mice (3∼5 mice/group) were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) on day 1 with 0.2 ml of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing 50 μg of OVA (ovalbumin, Sigma) in the presence or absence of alum (Sigma) or TLF. On Day 14, all mice were booster immunized by i.p. injection of 0.2 ml of PBS containing 50 μg of OVA. On day 21, immunized mice were euthanized to remove spleens. Spleens of each group of mice were collected and pooled to make single splenocyte suspension. OVA-specific splenocyte proliferation and/or cytokine production were measured as previously described with minor modifications (26). Briefly, splenocytes (5×105/well) were seeded in triplicate in wells of round-bottomed 96-well plates in complete RPMI1640 medium (0.2 ml/well) and incubated in the presence or absence of indicated concentration of OVA at 37°C in a CO2 incubator for 60 h. The cells were pulsed with 3H-TdR (1 μCi/well) for the last 18 h to assess splenocyte proliferation. Alternatively, pooled splenocytes of each group were cultured in complete RPMI1640 in 24-well plates (5×106/1 ml/well) with indicated concentrations of OVA for 48 h before the culture supernatants were harvested to determine their cytokine content (Pierce SearchLight multiplex ELISA).

Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed using paired two-tailed Student’s t-test comparing untreated samples with lactoferrin-treated or LPS-treated samples, using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc)

Results

Lactoferrin induces migration of human peripheral blood monocytes

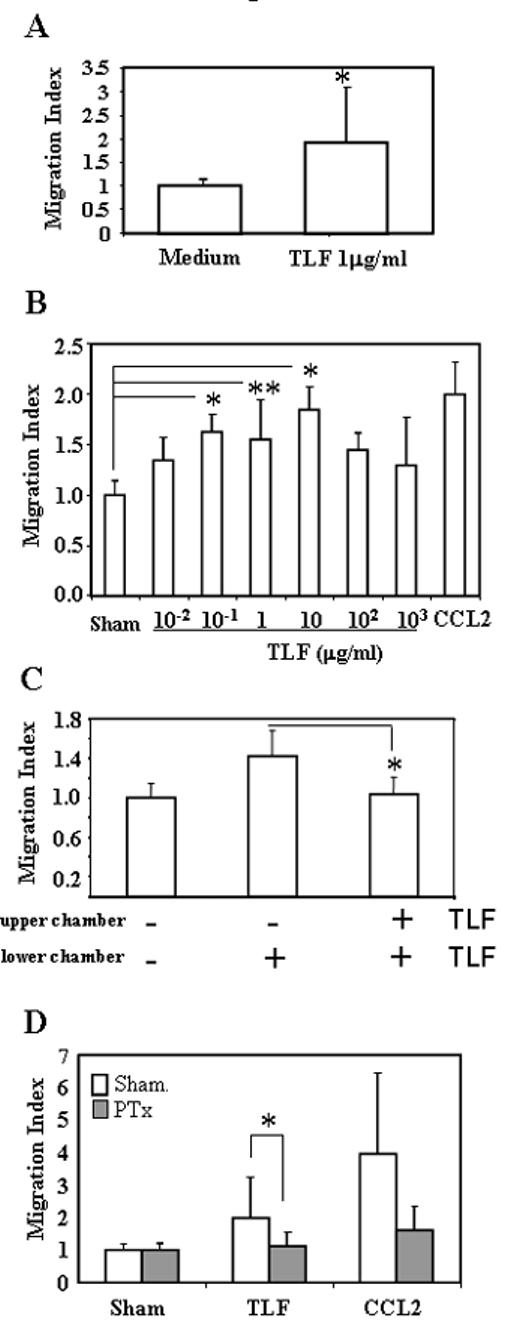

The chemotactic effect of recombinant human Lactoferrin (TLF) was tested in vitro with peripheral blood mononuclear cells in transwell migration assays. Monocytes consistently responded, but with low efficacy, whereas lymphocytes and peripheral blood dendritic cells did not migrate at all in response to lactoferrin (data not shown). Percoll-enriched neutrophils also failed to respond to TLF (not shown). The capacity of TLF to attract monocytes was confirmed using 48-well micro-chemotaxis chamber assays and monocytes purified by Percoll gradient centrifugation (Fig 1A; p<0.01). When dose-response experiments were performed, TLF ranging from 100 ng/ml to 10 μg/ml resulted in monocyte migration (Fig 1B). Lactoferrin-induced migration was inhibited when identical concentration of the protein was added to both the upper and lower chambers in a simple checkerboard experiment (Fig 1C) indicating that TLF-induced monocyte migration was chemotactic rather than chemokinetic. To investigate if lactoferrin-induced migration was mediated by a Giα protein-coupled receptor, monocytes were pre-treated with pertussis toxin (PTx). This toxin prevents Giα proteins association with membrane receptors, blocking the signaling cascade coming from those receptors. Pretreatment of monocytes for 1 h. with PTx inhibited the migration induced by lactoferrin, indicating that the chemotactic effect of TLF was based on an interaction with Giα -coupled receptor(s) (Fig 1D). Preliminary results suggested that lactoferrin could use CCR2 receptor. However, the chemotactic effect of TLF on monocytes couldn’t be blocked when the cells were loaded into the chamber in the presence of MCP-1/CCL2, and conversely, the chemotaxis of monocytes towards MCP-1 couldn’t be blocked by TLF at various concentrations, ruling out the possibility that the migration of monocytes to TLF was through CCR2 (not shown). Similarly, SDF-1alpha and IL-8 failed to desensitize TLF (not shown). Consequently, the chemotactic Gi-coupled receptor utilized by TLF remains unknown.

Fig. 1. TLF induces monocyte migration.

A) Monocyte migration was assayed using 48-well micro-chemotaxis chambers with the addition of monocytes (106/ml) and TLF in the upper and lower chambers, respectively. After 2 h of incubation, the membrane was scraped, fixed, and stained. Migrated monocytes were counted using Bioquant Life Science software. Results shown are the average +SD of seven experiments. *=p<0.01. B) Dose-response of monocyte migration to TLF. One experiment out of three is shown. C) Checkerboard analysis. Monocytes were allowed to migrate in the presence (+) of 1 μg/ml of TLF in the lower chamber or in both the upper and lower chambers. The results shown are the average (mean+SD) of three experiments. D) Effect of pertussis toxin (PTx). Monocytes were pretreated with 100 ng/ml PTx for 1 h at 37°C prior to utilization in the migration assay. 100ng/ml of CCL2 was used as a positive control for monocyte migration and to confirm the effect of PTx. The data show the average (mean+SD) of 4 experiments. *p<0.01; **p<0.05.

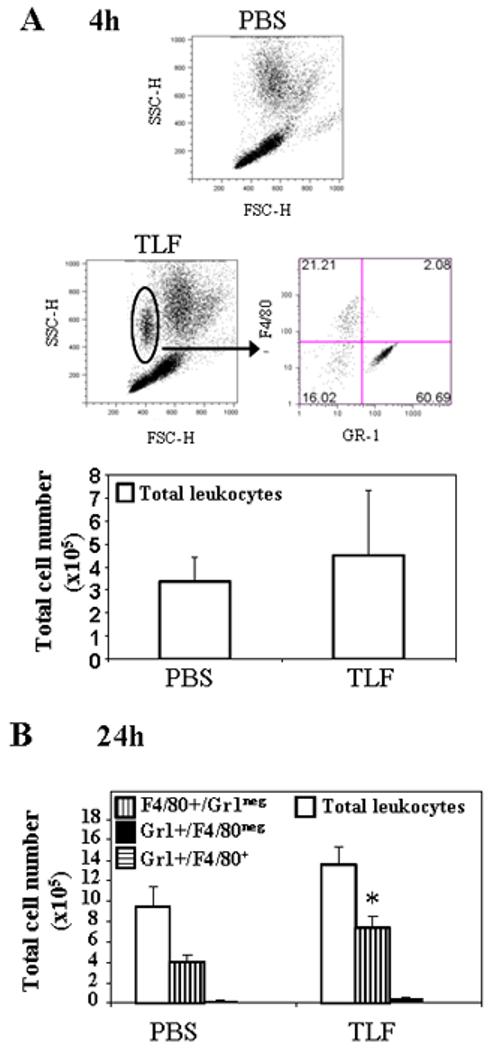

Lactoferrin causes recruitment of neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages in vivo

Next, we examined the in vivo chemotactic effects of Lactoferrin. TLF was injected into the peritoneal cavity of C57BL/6NCr mice to determine if it could induce in vivo infiltration of inflammatory cells at two different time points: After 4h, there was a clear recruitment of a subpopulation consisting mainly in Gr-1+/F4/80neg neutrophils (Fig 2A). After 24 h, that particular cell type had disappeared, but the numbers of infiltrating F4/80+/Gr-1neg monocytes/macrophages numbers were increased (p<0.01) (Fig 2B).

Fig. 2. Lactoferrin recruitment of neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages in vivo.

1 μg/ml of TLF or PBS was i.p. injected into C57BL/6 mice (n=3). After 4h (A) or 24h (B) mice were sacrificed and the peritoneal cavity was rinsed with 5 ml of cold PBS containing 5 mM EDTA to recover peritoneal leukocytes. The recovered cells were counted and stained to analyze the phenotype by flow cytometry. The result of one representative experiment out of three is shown. *=p<0.01.

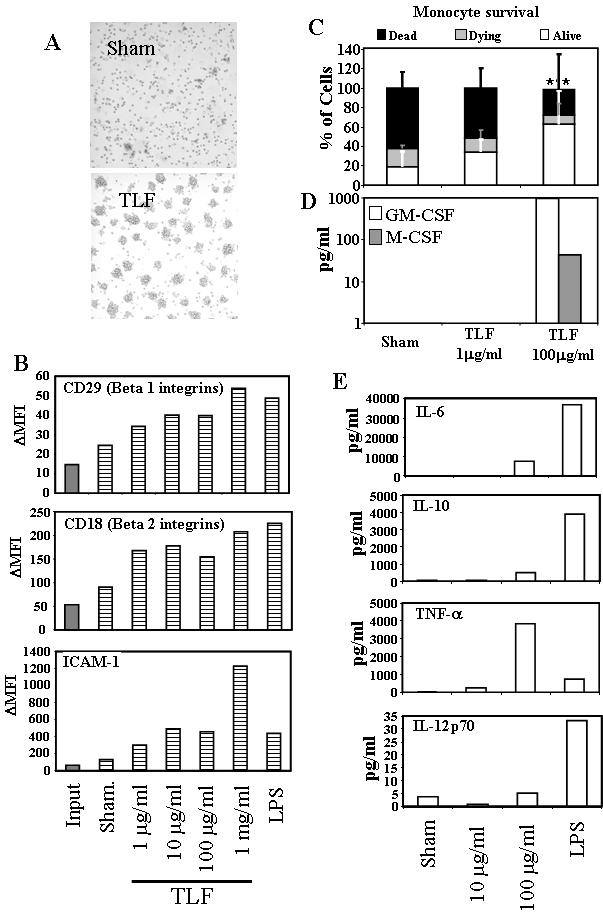

Lactoferrin promotes activation and survival of monocytes

In the course of treating monocytes with TLF, it was observed that the cells started to form clusters within 24 h (Fig. 3A). This process was presumed to be based on the activation of adhesion molecules (27). To confirm this, the surface expression levels of β1, β2 integrins and ICAM-1 in these monocytes was analyzed by flow cytometry. Concentrations of 1 μg/ml or higher of lactoferrin were able to induce a clear increase in the expression of both integrin types and ICAM-1 molecules (Fig. 3B) in the whole monocyte population. We also observed that the number of monocytes present in TLF-treated cultures was higher compared to the untreated samples. To determine if cell survival was affected after 48 h, cells were recovered, counted, compared with the number of cells plated at day 0 and analyzed for Annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) staining. TLF treatment dose-dependently rescued cultured monocytes from spontaneous apoptosis (Fig. 3C). While monocytes cultured in medium alone had a percentage of survival of 18.9±15.9, monocytes cultured in the presence of 100 μg/ml of TLF increased the survival to 63.0±33.6 (p<0.01). Analysis of GM-CSF and M-CSF levels in these supernatants showed that 100 μg/ml of TLF induced considerable production of these cytokines, which may explain the increase in cell survival of monocytes when in the presence of high concentrations of lactoferrin (fig 3D). We also determined whether TLF could induce other cytokine production by human monocytes. As shown by Fig. 3E, TLF at 100 μg/ml stimulated production of considerable IL-6 and TNF-α (>1000-fold increase compared to sham-treated cells). IL-10 levels were only doubled in response to TLF, whereas LPS induced a 1000-fold increase. There was no effect on IL-12p70 production.

Fig. 3. Lactoferrin activation of monocytes.

Monocytes were cultured at 106/ml in the presence or absence of TLF at different concentrations or LPS at 200 ng/ml for 48h. A) Microscopic images (20× magnification) showing cell distribution in monocyte cultures. TLF concentration = 10 μg/ml. B) Analysis by FACS of the expression of adhesion molecules in monocytes at day 0 (Input) and after 48 h (dashed bars) culture without or with lactoferrin or LPS. Mean fluorescence intensity increment (ΔMFI) was obtained by subtracting the MFI of the isotype control from the experimental MFI. The results of one representative experiment out of two is shown. (C) Monocytes were treated for 24 h under conditions specified and counted by flow cytometry and stained with FITC-conjugated annexin V and PI. Double-negative (DN) and annexin V+ events are plotted. Data is presented as % of cells relative to the initial population plated (100%) The results are the average (mean+SD) of four individual experiments. DN populations were compared to analyze statistical significance. **=p<0.05. (D and E) Supernatants of 48h-cultured monocytes were measured for cytokine concentrations. The results of one experiment representative of three and one out of two, respectively, are shown.

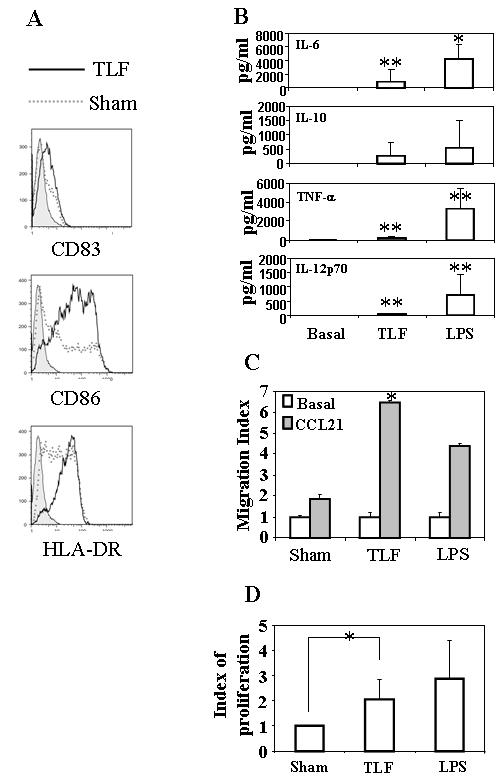

Lactoferrin induces DC maturation

DCs play an important role in inducing T cell responses, being the most potent antigen-presenting cell for initiating primary immune responses. The capacity of DCs to present antigens is dependent on their activation and maturation status (28). When TLF was added into human monocyte-derived dendritic cell (moDC) cultures, upregulation of co-stimulatory molecules such as CD80, CD83 and HLA-DR was observed (Fig. 4A). The increase in phenotypic maturation markers on moDCs was accompanied by an increase in the production of IL-6, TNF-α, and, IL-12p70 (Fig. 4B, p<0.05). In addition, moDCs upon treatment with TLF acquired the capacity to migrate to SLC/CCL21, suggesting induction of a functional CCR7 (Fig. 4C). To determine whether TLF-treated DCs were functionally mature, the capacity of TLF-treated DCs to induce allogeneic T cell proliferation in a mixed leukocyte reaction (MLR) was assayed. DCs treated with TLF stimulated greater proliferation of allogeneic lymphocytes than sham-treated DCs, indicating that DCs treated with TLF were functionally mature (Fig. 4D). These results indicate that Lactoferrin has the capacity to induce both phenotypic and functional maturation of moDCs.

Fig. 4. Lactoferrin induction of moDC activation.

(A). Monocyte-derived DCs (moDCs) were cultured in the absence (sham) or presence of TLF at 10 μg/ml. After 48 h, the expression of CD83, CD86 and HLA-DR was analyzed by flow cytometry. Shown is the overlay histograms of isotope-control (filled), sham (dashed lines), and TLF treatment (bold lines) of one experiment representative of seven. (B) Supernatants of moDCs cultured for 48 h in the absence (sham) or presence of TLF (10 μg/ml) or LPS (200 ng/ml) were measured for cytokines by ELISA. The results shown are the average (mean+SD) of five separate experiments (C) The migration of moDCs incubated in the absence (sham) or presence of TLF (10 μg/ml) or LPS (500 ng/ml) for 48 h in response to SLC/CCL21 were measured by 48-well microchemotaxis chamber assay. The results of one experiment representative of two are shown. (D) moDCs cultured without or with TLF (10 μg/ml) or LPS (1 μg/ml) for 48 h were mixed with allogeneic peripheral blood lymphocytes (105/well) at a ratio of 1:100 and cultured (in triplicate) for 4∼5 days. The cultures were pulsed with 3H-TdR (1 μCr/well) for the last 16 h before harvested for the measurement of 3H-TdR incorporation. Lymphocyte proliferation was shown as proliferation index, which was calculated as [CPM of the well with TLF- or LPS-treated DCs]/[CPM of the well with sham-treated DCs]. Data represent the average (mean+SD) of seven separate experiments. *=p<0.01; **=p<0.05.

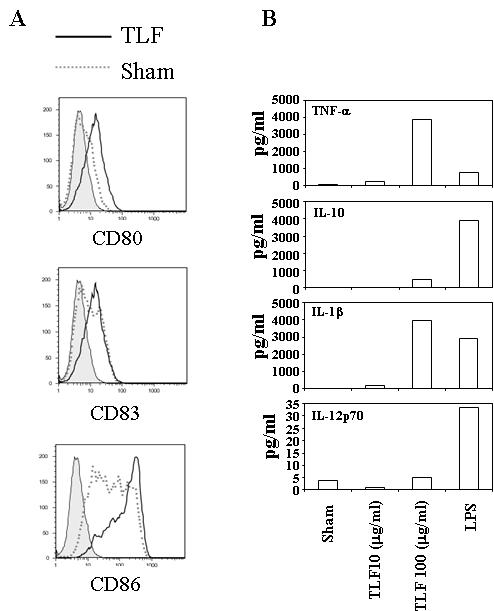

We also studied the effect of Lactoferrin on freshly-isolated CD1c+ peripheral blood dendritic cells (PBDCs). Although PBDCs undergo spontaneous maturation during in vitro cultures as reported previously (29), addition of TLF further enhanced the expression of CD80, CD83, and CD86 (Fig. 5A). In addition, PBDCs treated with TLF produced high amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and TNF-α (Fig. 5B). Therefore, TLF can induce the maturation of not only moDCs, but also PBDCs.

Fig. 5. Lactoferrin enhancement of the maturation of peripheral blood dendritic cells (PBDCs).

(A) PBMCs were cultured for 40 h in RPMI 1640 containing 5% FCS with or without TLF (100 μg/ml) or LPS (200 ng/ml). The cells were subsequently stained to analyze by flow cytometry CD80, CD83, and CD86 expression by gating on CD1c+ PBDCs subset. Data shown are the results of one experiment representative of four. B) Purified CD1c+ PBDCs were cultured (105/well) in RPMI-5%FCS for 48 h in the presence of TLF (10 μg/ml) or LPS (500 ng/ml). The supernatants were collected for the measurement of cytokine production. The results of one experiment representative of two are shown.

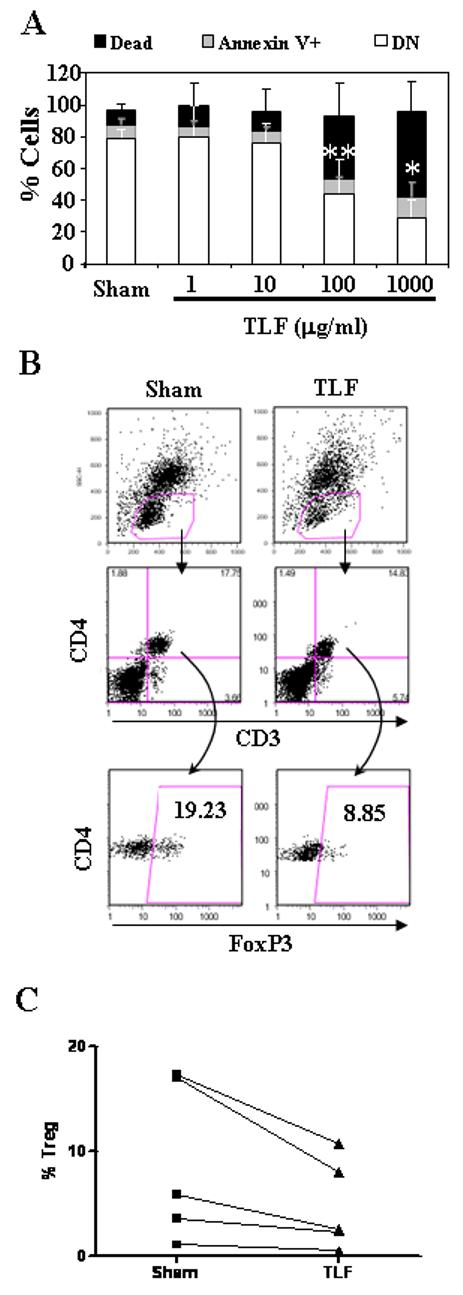

Lactoferrin reduces Treg in cultured PBMCs

Regulatory T lymphocytes (Treg) consist of a subset of CD4+ T cells that express the transcriptional factor FoxP3 and plays a critical role in downregulating immune activation (30). Because bovine lactoferrin has been shown to inhibit the proliferation of T cells (31), we determined whether TLF could also affect Tregs by incubating PBMCs in the absence or presence of TLF followed by analysis of Treg content. In contrast to promoting monocyte survival (Fig. 3C), TLF at high concentrations reduced the number of viable lymphocytes after 48 h culture (Fig. 6A). To look at the effect on Treg, PBMCs were cultured in medium containing low concentration of IL-2 (100 U/ml) and TNF-α (50 ng/ml) to prevent Treg from spontaneous apoptosis as reported previously (32). Interestingly, addition of TLF at 100 μg/ml in this culture system decreased the proportion of Treg (defined as CD3+/CD4+/FoxP3+) in comparison with sham-treated cultures (Fig. 6B and 6C), indicating that Tregs are more sensitive to TLF than other lymphocytes. TLF at 1μg/ml didn’t affect the Treg numbers (data not shown).

Fig. 6. Lactoferrin reduction of lymphocyte and Treg numbers in vitro cultured PBMCs.

A) PBMCs cultured at 1×106/ml in the absence (sham) or presence of TLF (1∼1000 μg/ml) for 48 h were stained with FITC-conjugated annexin V and PI and analyzed by flow cytometry. Lymphocytes were gated based on forward scatter and side scatter characteristics. Data is presented as % of cells respect to the initial population plated (100%); DN populations were compared to analyze statistical significance. B) and C) PBMCs were cultured in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS, 100 U/ml of IL-2, and 50 ng/ml of TNFα in the absence (sham) or presence of 100 μg/ml of TLF for 48 h. B) Subsequently, the cultured cells were stained for CD3, CD4, and FoxP3, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Dot plots show the phenotype of one representative experiment out of five and the numbers within each gate correspond to the percentage of gated events. C) The percentageof Treg (CD3+/CD4+/FoxP3+) within total CD3+ T lymphocyte population of five individual experiments are plotted.*=p<0.01; **=p<0.05.

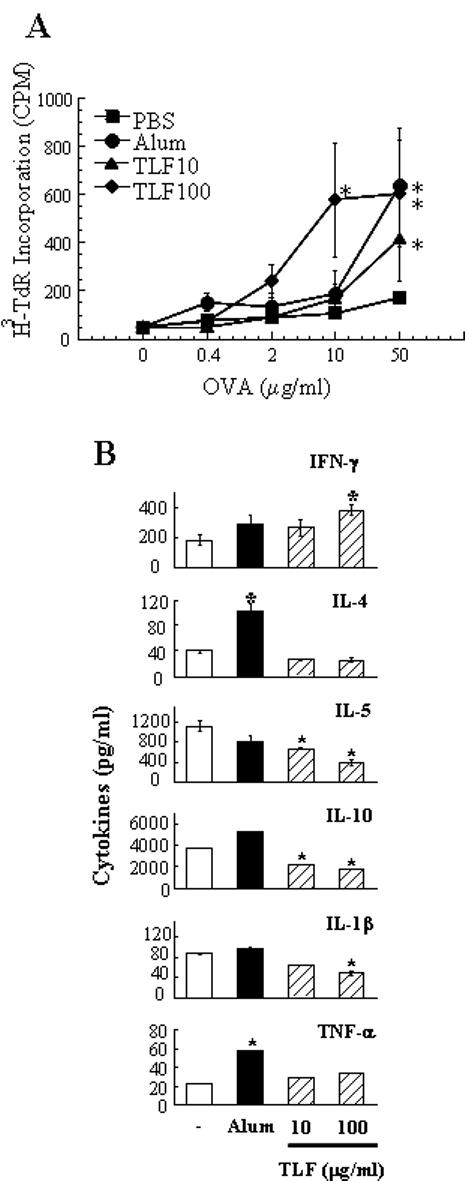

Lactoferrin enhances antigen-specific immune response

The capacity of TLF to activate APCs including monocytes and DCs suggested that it might act as an adjuvant to promote antigen-specific immune response. To validate this possibility, C57BL/6 mice were immunized with OVA in the absence or presence of TLF or alum (as a positive control) on day 0, boosted with OVA alone on day 14, and their spleens were removed on day 21 for the determination of OVA-specific proliferation and cytokine production. As expected, splenocytes from mice immunized with OVA in the presence of alum incorporated significantly more 3H-TdR than cells of mice immunized with OVA alone, particularly when the concentration of OVA used for in vitro stimulation reached 50 μg/ml (Fig. 7A). Importantly, splenocytes of mice immunized with OVA in the presence of TLF also showed enhanced proliferation upon in vitro stimulation with OVA (Fig. 7A), suggesting that TLF enhanced mouse anti-OVA immune response. Compared to splenocytes of negative control mice, splenocytes of mice immunized with antigen plus TLF, upon in vitro OVA stimulation, produced predominantly IFNγ with a simultaneous reduction in IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-1β, demonstrating the capacity of TLF to promote Th1 type T cell response (Fig. 7B). Alum, as expected, enhanced predominantly Th2 responses as evidenced by upregulation of IL-4, rather than IFN-γ (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7. Lactoferrin enhancement of antigen-specific immune response.

C56BL/6 mice (n=4) were i.p. immunized with OVA (50 μg/mouse) in the absence or presence of TLF or alum (as a positive control) on day 1, boosted i.p. with OVA alone on day 14, and euthanized on day 21 for the removal of spleens and preparation of single splenocyte suspension. (A) OVA-specific proliferation of splenocytes. Splenocytes were cultured in triplicate in a 96-well plate at 5×105/well in the presence of various concentrations of OVA for 60 h and pulsed with 0.5 μCi/well of 3H-TdR for the last 18 h. The proliferation of splenocytes was measured as 3H-TdR incorporation and shown as the average (mean±SD) of four mice. (B) Pooled splenocytes of each group were cultured in duplicate in a 24-well plate at 5×106/1 ml/well in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS and 50 μg/ml of OVA for 48 h before harvesting the supernatants for cytokine measurement. Shown are the average (mean±SD) cytokine concentration of duplicate wells. Similar results were obtained in two independent experiments *p<0.01 compared with the group immunized with OVA alone.

Discussion

Ever since its discovery almost 50 years ago, lactoferrin has been widely studied as an antimicrobial as well as a modulator of inflammation and immune defense (2, 10, 11, 15). More recently, TLF, a recombinant human lactoferrin has been shown to suppress the growth of implanted tumors in mouse models (16, 33) and to exhibit anti-tumor activity in phase I clinical trials (18). In this study, we have shown that TLF is able to: 1) chemoattract human monocytes in vitro and induce the recruitment of mouse phagocytes including neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages in vivo, 2) activate human APCs including monocytes/macrophages and DCs, 3) reduce human Treg content in cultured PBMCs, and 4) enhance antigen-specific mouse Th1 immune responses upon co-administration with the antigen. By using an FDA-approved, GMP level recombinant human lactoferrin generated in eukaryotic cells, this study avoids potential endotoxin contamination problem associated with the use of lactoferrins purified from bovine milk or generated in E. coli. Furthermore, human lactoferrin shares only 68% sequence with its bovine counterpart (21, 34-36). Therefore our results may have more relevance for understanding the effect(s) of lactoferrin on human immune cells and immunity than those studies in which the bovine lactoferrin was used (37-40).

Based on the inhibition of TLF-induced monocyte migration by pertussis toxin, it is clear that the capacity of TLF to chemoattract monocytes is direct and mediated by a Giα protein-coupled receptor(s), although the precise identity of the receptor(s) remains to be determined. In contrast to a previous report showing neutrophil mobility enhanced by lactoferrin (41), we did not detect any effect of TLF on the migration of human neutrophils nor on mouse neutrophils or monocytes in vitro (not shown) within a wide range of doses (0.1∼1000 μg/ml). However, intraperitoneal injection of TLF in mice did cause the recruitment of neutrophils to the peritoneal cavity within 4 h, illustrating an in vivo neutrophil-mobilizing capacity for TLF. This may be due to an indirect effect of lactoferrin inducing production of chemoattractants by cells present in the peritoneal cavity (macrophages or epithelial cells). Since monocytes may differentiate into DCs upon recruitment into tissues (42), lactoferrin’s capacity to induce the recruitment of monocytes/macrophages potentially promotes the accumulation of DCs at inflammatory sites where neutrophil infiltration and degranulation often occur. Lactoferrin can thus potentially enhance both innate and adaptive immunity.

Another critical finding of this study is the capacity of lactoferrin to activate APCs including monocytes/macrophages and DCs. TLF induced monocyte clustering due to an increase in the expression of adhesion molecules. TLF also rescued monocytes from the spontaneous in vitro apoptosis (43, 44). This is likely to be due to an induction in GM-CSF and M-CSF production by monocytes, which may help these precursor APCs to exert their surveillance function in the tissues for a longer period. TLF stimulated production of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α by monocytes at similar concentrations as reported for the promotion of monocyte cytotoxicity by purified bovine lactoferrin (45). While certain aspects of lactoferrin’s monocyte-activating effect has previously been sporadically reported (41, 45), the effect of lactoferrin on DC maturation remains to be determined. Here we have demonstrated for the first time the capacity of lactoferrin to induce the maturation of both moDCs and CD1c+ PBDCs. Coculture of moDCs with TLF resulted in upregulation of expression co-stimulatory and MHC molecules, induction of DC proinflammatory cytokines including IL-12p70, and DC acquisition of the capacity to migrate to lymphoid-homing chemokine SLC/CCL21 (Fig. 4). TLF also induced the maturation of CD1c+ PBDCs as evidenced by upregulation of costimulatory molecules (CD80, CD83, and CD86) and induction of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β (Fig. 5). Furthermore, DCs treated with TLF induced a greater lymphocyte proliferation compared to untreated cells in allogeneic cell cultures (Fig. 4D). Similar results were obtained by M. Giovarelli’s et al. when TLF was used to induce maturation of moDCs (personal communication). These activation effects indicate that lactoferrin can enable DCs to mature and develop the capacity to induce adaptive immune responses. Thus, only in danger conditions, when neutrophils are induced to release the content of their secondary granules, does lactoferrin become available to the recruited APCs at concentrations that favors their activation and maturation. We consider that doses around 100μg/ml might have relevant clinical importance, because of its critical effect on the survival and activation of antigen presenting cells, and this should be taken into consideration for future vaccines or treatments. As lactoferrin levels in milk, and especially in colostrum, are also very high, it is possible that lactoferrin also promotes development of the newborn immune system by activating APCs positioned along the GI tract, in addition to its antimicrobial capacities and the effect exerted on the intestinal epithelium (46).

It has been previously reported that lactoferrin can inhibit lymphocyte proliferation and cytokine production (31, 47). Our data showing the induction of lymphocyte death in cultured PBMCs by high doses (>100 μg/ml) of TLF may account for the reported inhibitory effect. Of substantial interest is our data showing that TLF caused a greater reduction of Treg (CD4+/FoxP3+) in cultured PBMCs (Fig. 6). Although how TLF suppresses Treg more than other lymphocytes in this culture system is unclear, this preferential reduction of Treg by TLD would definitively favor induction of immune responses.

Given the critical roles of APCs in the induction of immunity, the effects of TLF on APC migration, recruitment, activation/maturation, and Treg reduction suggest that lactoferrin may enhance antigen-specific immune response. Indeed, co-administration of TLF with an antigen (OVA) enhanced specific immune response in mice (Fig. 7). Many endogenous antimicrobial peptides and proteins have been documented to exhibit adjuvant effects, such as α-defensins, β-defensins, and cathelicidins (26, 48, 49). However, α-defensins and cathelicidin promote both Th1 and Th2 immune responses (26, 48) whereas β-defensin 2 preferentially enhances Th1 response (49). The TLF-enhanced anti-OVA immune response is predominantly of a Th1 type as evidenced by the upregulation of antigen-specific IFNγ production and a concomitant downregulation of IL-4 and IL-10. The capacity of bovine lactoferrin to enhance delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction (39) can easily be explained by lactoferrin’s Th1-polarizing effect demonstrated in our study. Therefore, lactoferrin is a promising adjuvant for use in cancer vaccines, because Th1 immune response is required for tumor rejection. In this regard, TLF has been shown to increase IFNγ production and cytotoxic capacity of T lymphocytes in tumor-implanted mice (33).

Lactoferrin concentrations in normal human secretions are reported to be 35 μg/ml in bronchial mucus, 46 μg/ml in synovial fluid, up to 2.2 mg/ml in lacrimal fluid, and 5∼7 mg/ml in colostrums (3, 15). During inflammation, lactoferrin levels in biologic fluids can increase more than 200-fold (6, 7). The effective concentrations of lactoferrin on monocyte migration, leukocyte recruitment, APC activation, and Treg reduction range from 1 to 1000 μg/ml, which is apparently achievable in vivo. While TLF-induced APC migration and recruitment occurs at low μg/ml levels, its effect on APC activation and Treg reduction become more obvious at ≥ 100 μg/ml. This may be relevant in the context of inflammatory and immune reactions: In the initial phase of inflammation, low concentration of lactoferrin may facilitate APC recruitment, while with the progression of inflammation, lactoferrin accumulates, due to additional neutrophil degranulation and induced production, to reach higher concentrations, which would promote DC maturation and reduce Treg, thereby promoting the induction of adaptive immune responses. As neutrophil infiltration is transient (50), and lactoferrin can be rapidly cleared by the liver (51), by the time antigen-specific effector lymphocytes traffic into sites of inflammation, it is likely that lowered lactoferrin levels would no longer be lymphotoxic.

Alarmins are defined as endogenous mediators rapidly released by cells of the host innate immune system in response to infection and/or tissue injury, which possess the dual activities of recruiting and activating APCs, and consequently are capable of enhancing antigen-specific adaptive immune responses (20, 52). Lactoferrin is an endogenous mediator rapidly released from neutrophils and many epithelial cells. The results of the present study demonstrate that lactoferrin is capable of inducing the recruitment and activation of APCs, thus enhancing antigen-specific immune response in vivo. Therefore, lactoferrin can be considered a bona fide alarmin that favors a Th1-type immune response.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. J. Roayaei, from Computer & Statistical Services, NCI-Frederick, for helpful data analysis suggestions.

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organization imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. This publication has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research National Cancer Institute and under Contract No. N01-CO-12400.

Abbreviations used in this article

- DC

dendritic cells

- moDC

monocyte-derived DC

- iDC

immature DC

- PBDC

Peripheral blood DC

- TLF

Talactoferrin-alpha

- Treg

Regulatory T lymphocyte

Footnotes

Disclosure: Dr. Varadhachary is an employee of Agennix Inc., developer of the talactoferrin alfa.

REFERENCES

- 1.Johanson B. Isolation of an iron-containing red protein from human milk. Acta Chem. Scand. 1960:510–512. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Montreuil J, Tonnelat J, Mullet S. [Preparation and properties of lactosiderophilin (lactotransferrin) of human milk.] Biochim Biophys Acta. 1960;45:413–421. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(60)91478-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Houghton MR, Gracey M, Burke V, Bottrell C, Spargo RM. Breast milk lactoferrin levels in relation to maternal nutritional status. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1985;4:230–233. doi: 10.1097/00005176-198504000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Masson PL, Heremans JF, Schonne E. Lactoferrin, an iron-binding protein in neutrophilic leukocytes. J Exp Med. 1969;130:643–658. doi: 10.1084/jem.130.3.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baggiolini M, De Duve C, Masson PL, Heremans JF. Association of lactoferrin with specific granules in rabbit heterophil leukocytes. J Exp Med. 1970;131:559–570. doi: 10.1084/jem.131.3.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bennett RM, Kokocinski T. Lactoferrin content of peripheral blood cells. Br J Haematol. 1978;39:509–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1978.tb03620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maaks S. Development and evaluation of luminescence based sandwich assay for plasma lactoferrin as a marker for sepsis and bacterial infections in pediatric medicine. J. Biolumines. Chemilumines. 1989;3:221–226. Y. H. Z. a. W. W. G. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fradin C, Mavor AL, Weindl G, Schaller M, Hanke K, Kaufmann SH, Mollenkopf H, Hube B. The early transcriptional response of human granulocytes to infection with Candida albicans is not essential for killing but reflects cellular communications. Infect Immun. 2007;75:1493–1501. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01651-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flach CF, Qadri F, Bhuiyan TR, Alam NH, Jennische E, Lonnroth I, Holmgren J. Broad up-regulation of innate defense factors during acute cholera. Infect Immun. 2007;75:2343–2350. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01900-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valenti P, Antonini G. Lactoferrin: an important host defence against microbial and viral attack. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:2576–2587. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5372-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bullen JJ, Rogers HJ, Leigh L. Iron-binding proteins in milk and resistance to Escherichia coli infection in infants. Br Med J. 1972;1:69–75. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5792.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Biase AM, Tinari A, Pietrantoni A, Antonini G, Valenti P, Conte MP, Superti F. Effect of bovine lactoferricin on enteropathogenic Yersinia adhesion and invasion in HEp-2 cells. J Med Microbiol. 2004;53:407–412. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.05410-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bellamy W, Takase M, Wakabayashi H, Kawase K, Tomita M. Antibacterial spectrum of lactoferricin B, a potent bactericidal peptide derived from the N-terminal region of bovine lactoferrin. J Appl Bacteriol. 1992;73:472–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1992.tb05007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamauchi K, Tomita M, Giehl TJ, Ellison RT., 3rd Antibacterial activity of lactoferrin and a pepsin-derived lactoferrin peptide fragment. Infect Immun. 1993;61:719–728. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.2.719-728.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Legrand D, Elass E, Carpentier M, Mazurier J. Lactoferrin: a modulator of immune and inflammatory responses. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:2549–2559. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5370-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Varadhachary A, Wolf JS, Petrak K, O’Malley BW, Jr., Spadaro M, Curcio C, Forni G, Pericle F. Oral lactoferrin inhibits growth of established tumors and potentiates conventional chemotherapy. Int J Cancer. 2004;111:398–403. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolf JS, Li G, Varadhachary A, Petrak K, Schneyer M, Li D, Ongkasuwan J, Zhang X, Taylor RJ, Strome SE, O’Malley BW., Jr. Oral lactoferrin results in T cell-dependent tumor inhibition of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1601–1610. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayes TG, Falchook GF, Varadhachary GR, Smith DP, Davis LD, Dhingra HM, Hayes BP, Varadhachary A. Phase I trial of oral talactoferrin alfa in refractory solid tumors. Invest New Drugs. 2006;24:233–240. doi: 10.1007/s10637-005-3690-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baveye S, Elass E, Fernig DG, Blanquart C, Mazurier J, Legrand D. Human lactoferrin interacts with soluble CD14 and inhibits expression of endothelial adhesion molecules, E-selectin and ICAM-1, induced by the CD14- lipopolysaccharide complex. Infect Immun. 2000;68:6519–6525. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.12.6519-6525.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oppenheim JJ, Yang D. Alarmins: chemotactic activators of immune responses. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17:359–365. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ward PP, Piddington CS, Cunningham GA, Zhou X, Wyatt RD, Conneely OM. A system for production of commercial quantities of human lactoferrin: a broad spectrum natural antibiotic. Biotechnology (N Y) 1995;13:498–503. doi: 10.1038/nbt0595-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson BF, Baker HM, Norris GE, Rice DW, Baker EN. Structure of human lactoferrin: crystallographic structure analysis and refinement at 2.8 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 1989;209:711–734. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90602-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jarrossay D, Napolitani G, Colonna M, Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A. Specialization and complementarity in microbial molecule recognition by human myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:3388–3393. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200111)31:11<3388::aid-immu3388>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de la Rosa G, Longo N, Rodriguez-Fernandez JL, Puig-Kroger A, Pineda A, Corbi AL, Sanchez-Mateos P. Migration of human blood dendritic cells across endothelial cell monolayers: adhesion molecules and chemokines involved in subset-specific transmigration. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;73:639–649. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1002516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacDonald KP, Munster DJ, Clark GJ, Dzionek A, Schmitz J, Hart DN. Characterization of human blood dendritic cell subsets. Blood. 2002;100:4512–4520. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-11-0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurosaka K, Chen Q, Yarovinsky F, Oppenheim JJ, Yang D. Mouse cathelin-related antimicrobial peptide chemoattracts leukocytes using formyl peptide receptor-like 1/mouse formyl peptide receptor-like 2 as the receptor and acts as an immune adjuvant. J Immunol. 2005;174:6257–6265. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Springer TA. Adhesion receptors of the immune system. Nature. 1990;346:425–434. doi: 10.1038/346425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steinman RM. The dendritic cell system and its role in immunogenicity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:271–296. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.001415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dieu MC, Vanbervliet B, Vicari A, Bridon JM, Oldham E, Ait-Yahia S, Briere F, Zlotnik A, Lebecque S, Caux C. Selective recruitment of immature and mature dendritic cells by distinct chemokines expressed in different anatomic sites. J Exp Med. 1998;188:373–386. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakaguchi S. Naturally arising Foxp3-expressing CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells in immunological tolerance to self and non-self. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:345–352. doi: 10.1038/ni1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moed H, Stoof TJ, Boorsma DM, von Blomberg BM, Gibbs S, Bruynzeel DP, Scheper RJ, Rustemeyer T. Identification of anti-inflammatory drugs according to their capacity to suppress type-1 and type-2 T cell profiles. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:1868–1875. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.02124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taams LS, Smith J, Rustin MH, Salmon M, Poulter LW, Akbar AN. Human anergic/suppressive CD4(+)CD25(+) T cells: a highly differentiated and apoptosis-prone population. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:1122–1131. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200104)31:4<1122::aid-immu1122>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spadaro M, Curcio C, Varadhachary A, Cavallo F, Engelmayer J, Blezinger P, Pericle F, Forni G. Requirement for IFN-gamma, CD8+ T lymphocytes, and NKT cells in talactoferrin-induced inhibition of neu+ tumors. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6425–6432. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baker EN, Baker HM. Molecular structure, binding properties and dynamics of lactoferrin. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:2531–2539. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5368-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crichton RR. Proteins of iron storage and transport. Adv Protein Chem. 1990;40:281–363. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60288-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nuijens JH, van Berkel PH, Schanbacher FL. Structure and biological actions of lactoferrin. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 1996;1:285–295. doi: 10.1007/BF02018081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cumberbatch M, Dearman RJ, Uribe-Luna S, Headon DR, Ward PP, Conneely OM, Kimber I. Regulation of epidermal Langerhans cell migration by lactoferrin. Immunology. 2000;100:21–28. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00014.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li KJ, Lu MC, Hsieh SC, Wu CH, Yu HS, Tsai CY, Yu CL. Release of surface-expressed lactoferrin from polymorphonuclear neutrophils after contact with CD4+ T cells and its modulation on Th1/Th2 cytokine production. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:350–358. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1105668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kocieba M, Zimecki M, Kruzel M, Actor J. The adjuvant activity of lactoferrin in the generation of DTH to ovalbumin can be inhibited by bovine serum albumin bearing alpha-D-mannopyranosyl residues. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2002;7:1131–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Curran CS, Demick KP, Mansfield JM. Lactoferrin activates macrophages via TLR4-dependent and -independent signaling pathways. Cell Immunol. 2006;242:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gahr M, Speer CP, Damerau B, Sawatzki G. Influence of lactoferrin on the function of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes and monocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 1991;49:427–433. doi: 10.1002/jlb.49.5.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Randolph GJ, Beaulieu S, Lebecque S, Steinman RM, Muller WA. Differentiation of monocytes into dendritic cells in a model of transendothelial trafficking. Science. 1998;282:480–483. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5388.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mangan DF, Wahl SM. Differential regulation of human monocyte programmed cell death (apoptosis) by chemotactic factors and pro-inflammatory cytokines. J Immunol. 1991;147:3408–3412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mangan DF, Welch GR, Wahl SM. Lipopolysaccharide, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and IL-1 beta prevent programmed cell death (apoptosis) in human peripheral blood monocytes. J Immunol. 1991;146:1541–1546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Horwitz DA, Bakke AC, Abo W, Nishiya K. Monocyte and NK cell cytotoxic activity in human adherent cell preparations: discriminating effects of interferon and lactoferrin. J Immunol. 1984;132:2370–2374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kuhara T, Yamauchi K, Tamura Y, Okamura H. Oral administration of lactoferrin increases NK cell activity in mice via increased production of IL-18 and type I IFN in the small intestine. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2006;26:489–499. doi: 10.1089/jir.2006.26.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Slater K, Fletcher J. Lactoferrin derived from neutrophils inhibits the mixed lymphocyte reaction. Blood. 1987;69:1328–1333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tani K, Murphy WJ, Chertov O, Salcedo R, Koh CY, Utsunomiya I, Funakoshi S, Asai O, Herrmann SH, Wang JM, Kwak LW, Oppenheim JJ. Defensins act as potent adjuvants that promote cellular and humoral immune responses in mice to a lymphoma idiotype and carrier antigens. Int Immunol. 2000;12:691–700. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.5.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Biragyn A, Surenhu M, Yang D, Ruffini PA, Haines BA, Klyushnenkova E, Oppenheim JJ, Kwak LW. Mediators of innate immunity that target immature, but not mature, dendritic cells induce antitumor immunity when genetically fused with nonimmunogenic tumor antigens. J Immunol. 2001;167:6644–6653. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Serhan CN, Savill J. Resolution of inflammation: the beginning programs the end. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1191–1197. doi: 10.1038/ni1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Debanne MT, Regoeczi E, Sweeney GD, Krestynski F. Interaction of human lactoferrin with the rat liver. Am J Physiol. 1985;248:G463–469. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1985.248.4.G463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang D, Oppenheim JJ. Antimicrobial proteins act as “alarmins” in joint immune defense. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:3401–3403. doi: 10.1002/art.20604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]