Abstract

PURPOSE:

To evaluate the effect of vascular occlusion on the size of radiofrequency (RF) ablation lesions and to evaluate embolization as an occlusion method.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

The kidneys of six swine were surgically exposed. Fifteen RF ablation lesions were created in nine kidneys by using a 2-cm-tip single-needle ablation probe in varying conditions: Seven lesions were created with normal blood flow and eight were created with blood flow obstructed by means of vascular clamping (n = 5) or renal artery embolization (n = 3). The temperature, applied voltage, current, and impedance were recorded during RF ablation. Tissue-cooling curves acquired for 2 minutes immediately after the ablation were compared by using regression analysis. Lesions were bisected, and their maximum diameters were measured and compared by using analysis of variance.

RESULTS:

The mean diameter of ablation lesions created when blood flow was obstructed was 60% greater than that of lesions created when blood flow was normal (1.38 cm ± 0.05 [standard error of mean] vs 0.86 cm ± 0.07, P < .001). The two methods of flow obstruction yielded lesions of similar mean sizes: 1.40 cm ± 0.06 with vascular clamping and 1.33 cm ± 0.07 with embolization. The temperature at the probe tip when lesions were ablated with normal blood flow decreased more rapidly than did the temperature when lesions were ablated after flow obstruction (P < .001), but no significant differences in tissue-cooling curves between the two flow obstruction methods were observed.

CONCLUSION:

Obstruction of renal blood flow before and during RF ablation resulted in larger thermal lesions with potentially less variation in size compared with the lesions created with normal nonobstructed blood flow. Selective arterial embolization of the kidney vessels may be a useful adjunct to RF ablation of kidney tumors.

Keywords: Animals; Experimental study; Kidney, interventional procedures, 81.1264, 81.1267, 81.1269; Kidney, perfusion; Radiofrequency (RF) ablation, 81.1269

Renal cell carcinoma is the most common primary malignancy of the kidney parenchyma, accounting for approximately 2% of all new cancers identified annually in the United States (1), and renal cell carcinomas greater than 3 cm in diameter are associated with an increased frequency of metastases (2,3). The treatment of renal cell carcinoma has greatly improved owing to advances in imaging modalities and surgical techniques (4,5), with the present reference-standard technique for treatment of renal tumors being radical nephrectomy. However, small localized renal tumors have also been successfully treated with partial nephrectomy (6-12). A minimally invasive treatment capable of causing the selective destruction of large tumors while preserving kidney function might have a positive effect on the outcomes of quality of life and dialysis-free survival.

Radiofrequency (RF) ablation is a relatively new minimally invasive image-guided tumor treatment. Although RF ablation has been used principally for the treatment of nonresectable liver tumors, in selected clinical settings it may represent an alternative to parenchyma-sparing surgery for the treatment of small renal malignancies with diameters of less than or equal to 3 cm (13-17).

The combination of selective renal artery embolization and RF ablation may increase the volume of the thermal lesion and thus could be useful in the treatment of tumors larger than 3 cm in diameter. Selective embolization results in decreased blood flow, which leads to a reduced amount of convective cooling and thus an increased extent of tissue heating. By performing selective arterial embolization, one may also decrease the possibility of hemorrhagic complications after RF ablation, which may be a greater risk with larger tumors.

We are aware of only one study of the effect of transcatheter vascular occlusion on RF ablation lesion size in the kidney. In that study, which was performed by Aschoff et al (18), the temporary balloon obstruction of renal blood flow in swine resulted in larger RF ablation lesions. Corwin et al (19) studied laparoscopic RF ablation of the kidneys with and without direct hilar occlusion in a swine model. They found that the lesions created with hilar occlusion in animals sacrificed 24 hours after the injury were larger than those created with normal blood flow. Thus, the purposes of our study were to evaluate the effect of vascular occlusion on the size of RF ablation lesions and to evaluate embolization as an occlusion method.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Six 250–300-pound (114–136 kg) crossbred swine (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Beltsville Area Research Center, Beltsville, Md) were used in this study. All animal care and use procedures were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Center for Veterinary Medicine. Up to two lesions were created in the kidneys of six swine, for a total of 15 lesions. Seven lesions were created without and eight were created with blood flow obstruction. Of the eight lesions created after vascular occlusion, five were created after vascular clamping and three were created after renal artery embolization.

Procedures and Data Collection

The surgical protocol followed in this study was designed to enable access to the liver and kidneys, with the animal first placed in a left lateral decubitus position. Therefore, lesions were generated in the right kidney before the animal was turned to allow surgical exposure of the left kidney. In all cases in which multiple lesions were created in a kidney, the lesions created with blood flow were produced before vascular clamping or embolization was performed. When more than one lesion was generated in a kidney, both lesions created with normal blood flow (ie, flow lesions) and those created after blood flow obstruction (ie, no-flow lesions) were produced, with the exception of one lesion in a left kidney in which embolization was performed.

Before the ablation procedure, anesthesia was induced with an intramuscularly injected mixture of tiletamine hydrochloride and zolazapam hydrochloride (Telazol; Fort Dodge, Overland Park, Kan) plus xylazine (Phoenix Pharmaceutical, St Joseph, Mo), followed by an intravenous injection of an anesthetic combination of tiletamine hydrochloride and zolazapam hydrochloride, xylazine, atropine sulfate (AmVet, Lexington, Ky), ketamine (Phoenix Pharmaceutical), and butorphanol tartrate (Torbugesic; Wyeth, Madison, NJ); this anesthetic regimen was described by Wray-Cahen et al (20). After the animals were placed in the supine position on the table, they were intubated and mechanically ventilated. General anesthesia was maintained with 2.5%–4.0% isoflurane (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, Ill). An author (D.W.C.) made longitudinal incisions to expose the kidneys.

A commercially available 200-W RF generator (CC1 Cosman Coagulator System; Radionics, Burlington, Mass) and a single- needle ablation probe with a 2-cm noninsulated tip (Radionics) were used without saline perfusion to create each lesion. The power was adjusted manually to maintain a temperature of 98°C at the tip of the probe for 10 minutes. To create each lesion, authors (I.M., W.F.P.) inserted the RF ablation probe through the margin of the kidney to a depth of 2 cm in either the upper, middle, or lower portion of the organ.

Blood flow was obstructed by using either vascular clamping or selective embolization. For blood flow obstruction with vascular clamping, the renal vasculature was exposed by means of blunt dissection and a loop of umbilical tape was placed around the renal pedicle. The loop was tightened by sliding a surgical suction tube over the umbilical tape to compress the vasculature and fixing the tube in place with a clamp to maintain occlusion for the duration of the RF ablation procedure and the subsequent cooling measurements (I.M., D.W.C.). For blood flow obstruction with embolization, arterial access was obtained via the femoral artery and the target renal artery was selectively catheterized with fluoroscopic guidance. The renal artery was embolized with 500–1,200-μm Embosphere particles (Biosphere Medical, Rockland, Mass) (W.F.P.). The end point of embolization was the absence of blood flow at angiography. The cessation of blood flow with both obstruction methods was confirmed at Doppler ultrasonography.

The applied voltage, power, current, and calculated root-mean-square impedance were recorded during each ablation session. In addition, the temperature measured with the thermistor at the probe tip was recorded during the RF ablation and for approximately 2 minutes afterward.

The animals were euthanized by means of exsanguination immediately after the final RF ablation procedure was performed in each animal. The kidneys were removed, and the ablation lesions were bisected for gross examination. To identify the lesion margin, selected lesions were immediately placed in a 1% 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (red) solution for 20 minutes to stain the tissue that contained active dehydrogenase, an indicator of cell viability (21). The maximum width (perpendicular to the long axis of the RF ablation probe) and the depth of the macroscopically pale ablated area were measured by authors (D.W.C., I.M., W.F.P.).

Statistical Analyses

Analysis of variance of the lesion dimensions, RF ablation parameters, and measured temperatures was performed by using the following two comparisons: flow versus no-flow lesions and clamping- versus embolization-induced flow obstruction (ie, the two no-flow methods were compared). The applied voltage, power, current, and calculated root-mean-square impedance during the ablation, as well as the temperature measured at the probe tip during and after the ablation, also were compared. All lesions were assumed to be independent in the statistical analysis. Since the renal vasculature bifurcates early, each ablated region has an independent blood supply and should not be affected by prior ablations within the kidney. To ensure the independence of lesions in the cases in which multiple lesions were created in the same kidney, the first ablation was performed with normal flow and the second ablation was performed without blood flow.

Nonlinear regression was used to analyze the tissue-cooling curves, which indicate the temperatures measured at the RF ablation probe tip during the cooling period after ablation. A two-phase exponential decay equation was used to fit the data, and 95% CIs were constructed for each curve and its parameters. In addition, linear regressions of the first 5 seconds of each cooling curve were used to determine the initial rate of decrease in temperature at the lesion site, and the slopes of these curves were compared. All statistical comparisons were performed by using computer software (GraphPad Prism, version 3.00 for Windows; Graph-Pad Software, San Diego, Calif). P < .05 indicated statistically significant differences between groups. All values are reported as means ± standard errors of the means.

RESULTS

Lesion Size

The mean maximum diameters of the RF ablation lesions created with obstructed blood flow (by means of vascular clamping or selective arterial embolization) were 60% greater than the mean maximum diameters of the lesions created with normal blood flow (1.38 cm ± 0.05 vs 0.86 cm ± 0.07, P < .001). The method of occlusion did not significantly affect lesion diameters (1.40 cm ± 0.06 with vascular clamping vs 1.33 cm ± 0.07 with embolization). The variation in diameter of the flow lesions was numerically greater than that of the no-flow lesions (variance, 0.033 vs 0.016 cm2; P = .19). The depth of the ablated region was not significantly influenced by the presence or absence of blood flow or the method of obstruction in the no-flow cases. The mean depths were 2.03 cm ± 0.11 for the ablated regions created with normal blood flow, 2.08 cm ± 0.04 for the regions created with vascular clamping, and 2.27 cm ± 0.15 for the regions created with embolization. Individual lesion size data are presented in Table 1. Representative examples of lesions created in normal flow conditions and with each method of blood flow obstruction are shown in Figures 1 and 2.

TABLE 1.

Widths and Depths of Renal Ablation Lesions Created with and without Blood Flow Obstruction

| Lesion Width (cm) |

Lesion Depth (cm) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Lesion Location* | Normal Flow† |

No Flow‡ |

Normal Flow† |

No Flow‡ |

||

| Clamp | Emb | Clamp | Emb | ||||

| Animal | |||||||

| 1 | L, lower region | 1.0 | 2.1 | ||||

| 1 | L, middle region | 1.5 | 2.1 | ||||

| 1 | R, lower region | 1.5 | 2.1 | ||||

| 1 | R, upper region | 1.0 | 2.1 | ||||

| 2 | R, lower region | 1.0 | 2.1 | ||||

| 2 | R, upper region | 1.5 | 2.0 | ||||

| 3 | R, lower region | 1.3 | 2.2 | ||||

| 3 | R, upper region | 1.0 | 2.1 | ||||

| 4 | L, middle region | 0.7 | ND§ | ||||

| 4 | R, lower region | 0.7 | 1.5 | ||||

| 4 | R, upper region | 1.4 | 2.5 | ||||

| 5 | L, lower region | 1.2 | 2.0 | ||||

| 5 | L, middle region | 1.4 | 2.3 | ||||

| 5 | R, lower region | 0.6 | 2.3 | ||||

| 6 | L, middle region | 1.2 | 2.0 | ||||

| Mean value | NA | 0.86 | 1.40 | 1.33 | 2.03 | 2.08 | 2.27 |

| SEM | NA | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.15 |

| Number of animals | NA | 7 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 3 |

Note.—Comparison results: RF ablation had a significant effect on the widths of the ablation lesions (P < .001) but a nonsignificant effect on the depths of the ablation lesions. The difference in the effect of RF ablation on lesion width between the lesions created with and those created without blood flow obstruction was significant (P < .001), but the difference in this effect on lesion depth between the two lesion groups was not. There was no significant difference in the effect of treatment on the widths or depths of the ablation lesions between the lesions created with blood flow obstruction by means of clamping and those created with blood flow obstruction by means of embolization.

L = left, NA = not applicable, R = right.

Blood flow to the kidney was not obstructed.

Blood flow to the kidney was obstructed by means of manual clamping (Clamp) or selective embolization (Emb). For all eight lesions created with blood flow obstruction (No Flow), the overall mean lesion width was 1.38 cm, with a standard error of the mean (SEM) of 0.05; and the overall mean lesion depth was 2.10 cm, with an SEM of 0.03.

ND = not determined.

Figure 1.

Ablation lesions (arrows) created with renal vasculature clamping (left) and normal blood flow (right) in one swine by using a steady-state temperature of 98°C for 10 minutes. The lesion specimens were incubated for 10 minutes with 1% 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (red) solution, which stains viable tissue red, and then fixed in formalin. The dimensions (maximum width × depth) of the lesions were 1.5 × 2.0 cm with vasculature clamping and 1.0 × 2.1 cm with normal blood flow.

Figure 2.

Ablation lesions (arrows) created (a) following selective embolization of the renal vasculature to angiographic stasis and (b) with normal blood flow in one swine by using a steady-state temperature of 98°C for 10 minutes. The lesion specimens shown were fixed in formalin and not stained. The dimensions (maximum width × depth) of the lesions were 1.4 × 2.3 cm following embolization and 0.6 × 2.3 cm with normal blood flow.

RF Ablation Parameters

The blood flow conditions in the kidneys did not affect any operating parameters of the RF generator (ie, power, current, applied voltage, and impedance) that were measured in this study (Table 2). There were no significant differences in temperatures measured at the probe tip during ablation among the compared groups.

TABLE 2.

Physical Parameter Values Achieved with RF Energy and a Steady-State Temperature of 98°C

| Temperature (°C) |

Impedance (Ω) |

Power (W) |

Voltage (V) |

Current (mA) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM |

| Normal flow* | 97.82 | 0.15 | 56.81 | 2.98 | 10.59 | 2.18 | 24.21 | 2.11 | 459 | 49 |

| No flow | ||||||||||

| Clamp† | 97.59 | 0.11 | 59.20 | 2.87 | 7.52 | 0.91 | 21.08 | 0.84 | 383 | 30 |

| Emb‡ | 97.34 | 0.52 | 59.57 | 0.50 | 6.95 | 0.25 | 20.65 | 0.44 | 365 | 5 |

Note.—Data are mean values averaged during the last 6–7 minutes of a 10-minute RF ablation session and standard error of the mean (SEM) values. There were no significant differences in any of the listed parameter values between either the normal flow and no-flow lesion groups or the clamp obstruction and embolization obstruction (Emb) groups (P > .05).

Blood flow to the kidney was not obstructed in the creation of seven lesions.

Blood flow to the kidney was obstructed by means of manual clamping in the creation of five lesions.

Blood flow to the kidney was obstructed by means of selective embolization in the creation of three lesions.

Cooling Temperatures

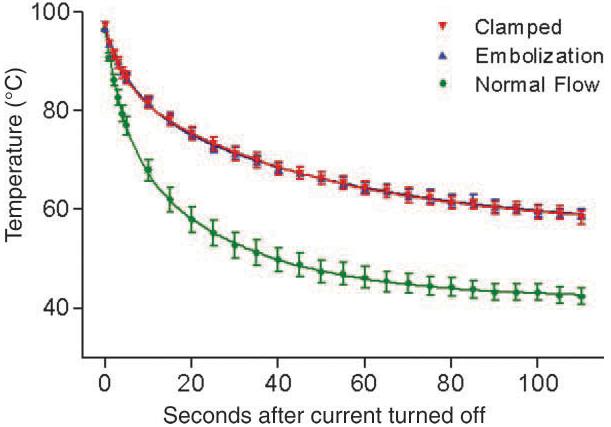

During the cooling period following ablation, the tissue-cooling curves for the two different methods of blood flow obstruction were similar (Fig 3). In contrast, the tissue-cooling curves for the lesions with a normal blood supply rapidly diverged from the curves for the lesions created with blood flow obstruction. At the end of the postablation temperature-recording period (110 seconds), the temperature recorded at the ablation probe tip was 38% higher in the lesions created with blood flow obstruction. All curves were well defined by using a two-phase exponential decay equation (R2 = 0.98).

Figure 3.

Tissue-cooling curves with normal flow, vascular clamping, and embolization during the first 110 seconds after the completion of RF energy deposition. Symbols represent the mean values for each treatment at each time point. Error bars represent standard errors of the mean for each treatment at each time point. The lines represent the two-phase exponential decay curves for each treatment, calculated by using nonlinear regression. The tissue-cooling curves for the two blood flow obstruction methods were similar. There was more rapid cooling of the lesions created with normal blood flow; the tissue-cooling curve for this treatment rapidly diverged from the curves for blood flow obstruction.

The initial decrease in temperature at the ablation probe tip was much more rapid for the lesions with normal flow; the slope was 90% greater than that observed with obstructed blood flow (−3.85°C/sec ± 0.31 vs −2.02°C/sec ± 0.13, P < .001). The linear regression parameters for the first 5 seconds of cooling were similar between the two flow obstruction methods. The mean slopes for the initial decrease in temperature for lesions created after clamping or embolization were −2.09°C/sec ± 0.23 and −1.96°C/sec ± 0.13, respectively. The y intercepts for all of the regression lines were very similar, reflecting the similar starting temperatures with all treatments (Table 2). For all linear regression lines, R2 was 0.84 or greater.

DISCUSSION

Proposed indications for RF ablation of kidney tumors include hereditary renal tumors, contraindications to surgery, solitary kidney, and renal insufficiency (13,15-17,22-24). However, tissue perfusion and blood flow through vessels near the target ablation site may affect the size and contour of the ablation lesion. In the liver, decreasing preprocedural blood flow leads to an increased ablation volume and allows ablation of tumor tissues adjacent to vessels (25-32). In addition, the combination therapy of embolization and RF ablation has been used successfully to treat solid renal tumors without any indication of toxicity (13,22).

In the present study, the obstruction of blood flow to the ablation site resulted in mean ablation lesion diameters that were 60% greater than the diameters of lesions created in normal blood flow conditions, and there was no overlap in the ranges of lesion diameters for the two groups. These results are consistent with the results of Aschoff et al (18); in that study, perfusion was reduced by means of balloon occlusion of the renal artery. The mean sizes of lesions produced with and of those produced without vascular occlusion in the Aschoff et al study, 1.42 cm ± 0.22 and 0.80 cm ± 0.26, respectively, were comparable to the results in the current study, in which the mean lesion diameters were 1.38 cm ± 0.05 and 0.86 cm ± 0.07, respectively. These results support the application of the described blood flow obstruction techniques as a means of enhancing the RF ablation of renal lesions.

The described results may be better understood by examining the bioheat transfer equation, as originally described by Pennes in 1948 (33,34) and modified here to account for RF heating. The bioheat equation balances the accumulation of heat in tissue,

with the sum of the terms describing heat loss and heat sources—specifically, conductive heat loss (∇[k∇T]), convective heat loss due to perfusion (ρbcbωb[Ta − T]), RF heating, and metabolic heating:

| (1) |

where ρ is the tissue density (in kilograms per cubic meter); c, the heat capacity of the tissue (in joules per kilogram-degrees Celsius); k, the thermal conductivity of the tissue (in watts per kelvin-meter); T, the temperature (in degrees Celsius); t, the = time; ∇, the gradient operator; ρb, the density of blood (in kilograms per cubic meter); cb, the heat capacity of blood (in joules per kilogram-degrees Celsius); ωb, the volumetric perfusion rate, expressed as the volume of blood per unit volume of tissue per unit time; Ta, the ambient temperature of the kidney (in degrees Celsius); qRF, the rate of heat generation by means of deposition of RF energy; and qm, the rate of heat generation by means of tissue metabolism.

When blood flow is obstructed,, the tissue perfusion, or ωb, is zero, and, therefore, heat loss at the ablation site occurs only by means of thermal conduction, as follows:

| (2) |

As the ablation proceeds, the metabolic heat source, or qm, also becomes zero in the area of coagulation necrosis.

The size of the ablation lesion in the absence of blood flow was not influenced by the method of blood flow obstruction (ie, vascular clamping or intraarterial embolization). Although the small sample size may have masked potential differences between the obstruction methods, the mean values were numerically similar and are comparable to those calculated by Aschoff et al (18). There is unlikely to be a difference in the size of the ablation lesion based on the method of blood flow obstruction. In this study, the entire kidney was embolized until no blood flow was apparent at angiography; however, subselective arterial embolization may result in the ischemia being limited to the target area while retaining the advantages of minimally invasive interventions.

The rate of cooling at the probe tip correlated with the presence or absence of renal blood flow: There was a 90% faster rate of temperature decrease with normal perfusion as compared with the temperature decrease with blood flow obstruction. When the application of RF energy is terminated, the rate of heat generation by means of RF energy deposition, or qRF, becomes zero. If blood flow is present, the bioheat equation can be simplified as follows:

| (3) |

Although the perfusion, or ωb, within the ablation lesion may be zero due to tissue coagulation, the perfusion of the adjacent tissues will contribute to the dissipation of heat and thus result in a higher rate of cooling, as observed in this study. Although the metabolic source value, or qm, also is expected to be zero within the ablation lesion, it still contributes to heat generation in the nonablated tissue. With the obstruction of blood flow, the bioheat equation during cooling can be further simplified as follows:

| (4) |

with heat dissipation or cooling occurring only by means of thermal conduction.

The observed tissue-cooling curves for vascular clamping and embolization were nearly identical. This finding implies that the method used to achieve blood flow obstruction does not affect the manner in which heat is dissipated and that both flow-obstructing methods are equally effective at stopping blood flow to the lesion. The similar slopes of the initial decreases in temperature at linear regression analysis are further evidence of the similarity in cooling mechanism between the two methods of occlusion and of the slower cooling with obstruction as compared with the rate of cooling with normal blood flow conditions.

In addition to a larger lesion size, another advantage of blood flow obstruction may be the production of a more predictable lesion size. The no-flow lesion group tended to have less variation in mean diameter than did the lesions created with normal blood flow (P = .19). Further work is required to confirm this observation.

Practical applications

Obstruction of renal blood flow before and during RF ablation resulted in larger ablation lesions and potentially less variation in lesion size compared with the lesions created with normal nonobstructed blood flow. The results seen following occlusion with selective arterial embolization of the kidney vessels were similar to those seen following occlusion with renal vessel clamping. These results indicate that selective arterial embolization of tumor vasculature may be a useful adjunct to RF ablation of renal lesions. This is especially true for tumors that are large, hypervascular, or adjacent to large blood vessels. The combination of embolization and RF ablation may result in larger lesions with a potentially more predictable size, but it could also introduce new risks. Balloon occlusion could provide similar benefits with less risk to the normal parenchyma. However, permanent occlusion with embolization may better enhance tumor cell death at the margins of the RF ablation lesion owing to prolonged ischemia. Further studies of the safety and effectiveness of this combined procedure are warranted.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Stephen Hilbert, PhD, MD, for performing pathologic analyses of the renal specimens. We also acknowledge the efforts of Brian B. Beard, PhD, and LT George Borlase for their efforts in interpreting data and editing the manuscript. In addition, we acknowledge the assistance of Kathleen Carmody for animal care and technical support; Richard Cullison, DVM, Samuel Howard, Mark Henderson, and Mark McDonald for animal care support; and Gary Kamer, MS, in the statistical analyses described in this article.

Abbreviation

- RF

radiofrequency

Footnotes

Sponsored by the Department of Diagnostic Radiology, National Institutes of Health, Warren Grant Magnuson Clinical Center.

The mention of commercial products, their sources, or their use in connection with material reported herein is not to be construed as either an actual or implied endorsement of such products by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the Public Health Service.

References

- 1.Landis SH, Murray T, Bolden S, Wingo PA. Cancer statistics, 1999. CA Cancer J Clin. 1999;49:8–31. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.49.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frank W, Guinan P, Stuhldreher D, Saffrin R, Ray P, Rubenstein M. Renal cell carcinoma: the size variable. J Surg Oncol. 1993;54:163–166. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930540307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walther MM, Choyke PL, Glenn G, et al. Renal cancer in families with hereditary renal cancer: prospective analysis of a tumor size threshold for renal parenchymal sparing surgery. J Urol. 1999;161:1475–1479. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)68930-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith SJ, Bosniak MA, Megibow AJ, Hulnick DH, Horii SC, Raghavendra BN. Renal cell carcinoma: earlier discovery and increased detection. Radiology. 1989;170:699–703. doi: 10.1148/radiology.170.3.2644658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bosniak MA, Rofsky NM. Problems in the detection and characterization of small renal masses. Radiology. 1996;200:286–287. doi: 10.1148/radiology.200.1.286-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Provet J, Tessler A, Brown J, Golimbu M, Bosniak M, Morales P. Partial nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma: indications, results and implications. J Urol. 1991;145:472–476. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38371-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Selli C, Lapini A, Carini M. Conservative surgery of kidney tumors. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1991;370:9–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Novick AC, Streem S, Montie JE, et al. Conservative surgery for renal cell carcinoma: a single-center experience with 100 patients. J Urol. 1989;141:835–839. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)41026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Licht MR, Novick AC. Nephron sparing surgery for renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 1993;149:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35982-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morgan WR, Zincke H. Progression and survival after renal-conserving surgery for renal cell carcinoma: experience in 104 patients and extended followup. J Urol. 1990;144:852–857. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)39608-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee CT, Katz J, Shi W, Thaler HT, Reuter VE, Russo P. Surgical management of renal tumors 4 cm or less in a contemporary cohort. J Urol. 2000;163:730–736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fergany AF, Hafez KS, Novick AC. Long-term results of nephron sparing surgery for localized renal cell carcinoma: 10-year followup. J Urol. 2000;163:442–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall WH, McGahan JP, Link DP, deVere White RW. Combined embolization and percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of a solid renal tumor. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:1592–1594. doi: 10.2214/ajr.174.6.1741592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rendon RA, Gertner MR, Sherar MD, et al. Development of a radiofrequency based thermal therapy technique in an in vivo porcine model for the treatment of small renal masses. J Urol. 2001;166:292–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zlotta AR, Wildschutz T, Raviv G, et al. Radiofrequency interstitial tumor ablation (RITA) is a possible new modality for treatment of renal cancer: ex vivo and in vivo experience. J Endourol. 1997;11:251–258. doi: 10.1089/end.1997.11.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGovern FJ, Wood BJ, Goldberg SN, Mueller PR. Radio frequency ablation of renal cell carcinoma via image guided needle electrodes. J Urol. 1999;161:599–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gervais DA, McGovern FJ, Wood BJ, Goldberg SN, McDougal WS, Mueller PR. Radio-frequency ablation of renal cell carcinoma: early clinical experience. Radiology. 2000;217:665–672. doi: 10.1148/radiology.217.3.r00dc39665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aschoff AJ, Sulman A, Martinez M, et al. Perfusion-modulated MR imaging-guided radiofrequency ablation of the kidney in a porcine model. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177:151–158. doi: 10.2214/ajr.177.1.1770151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corwin TS, Lindberg G, Traxer O, et al. Laparoscopic radiofrequency thermal ablation of renal tissue with and without hilar occlusion. J Urol. 2001;166:281–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wray-Cahen D, Vossoughi J, Karanian JW. Large animal models in pre-clinical trials. In: Vossoughi J, Kipshidze N, Karanian JW, editors. Stent graft update. Medical and Engineering Publications; Washington, DC: 2000. pp. 201–214. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kloner RA, Darsee JR, DeBoer LWV, Carlson N. Early pathologic detection of acute myocardial infarction. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1981;105:403–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tacke J, Mahnken A, Bucker A, Rohde D, Gunther RW. Nephron-sparing percutaneous ablation of a 5 cm renal cell carcinoma by superselective embolization and percutaneous RF-ablation. Rofo Fortschr Geb Rontgenstr Neuen Bildgeb Verfahr. 2001;173:980–983. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-18309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yohannes P, Pinto P, Rotariu P, Smith AD, Lee BR. Retroperitoneoscopic radiofrequency ablation of a solid renal mass. J Endourol. 2001;15:845–849. doi: 10.1089/089277901753205870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pautler SE, Pavlovich CP, Mikityansky I, et al. Retroperitoneoscopic-guided radiofrequency ablation of renal tumors. Can J Urol. 2001;8:1330–1333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patterson EJ, Scudamore CH, Owen DA, Nagy AG, Buczkowski AK. Radiofrequency ablation of porcine liver in vivo: effects of blood flow and treatment time on lesion size. Ann Surg. 1998;227:559–565. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199804000-00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rossi S, Garbagnati F, De Francesco I, et al. Relationship between the shape and size of radiofrequency induced thermal lesions and hepatic vascularization. Tumori. 1999;85:128–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aschoff AJ, Merkle EM, Wong V, et al. How does alteration of hepatic blood flow affect liver perfusion and radiofrequency-induced thermal lesion size in rabbit liver? J Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;13:57–63. doi: 10.1002/1522-2586(200101)13:1<57::aid-jmri1009>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Denys AL, De Baere T, Mahe C, Sabourin JC, Cunha AS, Germain S. Radio-frequency ablation of the liver: effects of vascular occlusion on lesion diameter and biliary and portal damages in a pig model. Eur Radiol. 2001;11:2102–2108. doi: 10.1007/s003300100973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chinn SB, Lee FT, Jr, Kennedy GD, et al. Effect of vascular occlusion on radiofrequency ablation of the liver: results in a porcine model. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:789–795. doi: 10.2214/ajr.176.3.1760789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu DS, Raman SS, Vodopich DJ, Wang M, Sayre J, Lassman C. Effect of vessel size on creation of hepatic radiofrequency lesions in pigs: assessment of the “heat sink” effect. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178:47–51. doi: 10.2214/ajr.178.1.1780047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rossi S, Garbagnati F, Lencioni R, et al. Percutaneous radio-frequency thermal ablation of nonresectable hepatocellular carcinoma after occlusion of tumor blood supply. Radiology. 2000;217:119–126. doi: 10.1148/radiology.217.1.r00se02119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Baere T, Bessoud B, Dromain C, et al. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of hepatic tumors during temporary venous occlusion. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178:53–59. doi: 10.2214/ajr.178.1.1780053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pennes HH. Analysis of tissue and arterial blood temperatures in the resting human forearm. J Appl Physiol. 1948;1:93–122. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1948.1.2.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements . I. Criteria based on thermal mechanisms. National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements; Bethesda, Md: 1992. Exposure criteria for medical diagnostic ultrasound. report no. 113. [Google Scholar]