Abstract

Heterotrimeric G proteins are signaling molecules ubiquitous among all eukaryotes. The Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) genome contains one Gα (GPA1), one Gβ (AGB1), and two Gγ subunit (AGG1 and AGG2) genes. The Gβ requirement of a functional Gγ subunit for active signaling predicts that a mutant lacking both AGG1 and AGG2 proteins should phenotypically resemble mutants lacking AGB1 in all respects. We previously reported that Gβ- and Gγ-deficient mutants coincide during plant pathogen interaction, lateral root development, gravitropic response, and some aspects of seed germination. Here, we report a number of phenotypic discrepancies between Gβ- and Gγ-deficient mutants, including the double mutant lacking both Gγ subunits. While Gβ-deficient mutants are hypersensitive to abscisic acid inhibition of seed germination and are hyposensitive to abscisic acid inhibition of stomatal opening and guard cell inward K+ currents, none of the available Gγ-deficient mutants shows any deviation from the wild type in these responses, nor do they show the hypocotyl elongation and hook development defects that are characteristic of Gβ-deficient mutants. In addition, striking discrepancies were observed in the aerial organs of Gβ- versus Gγ-deficient mutants. In fact, none of the distinctive traits observed in Gβ-deficient mutants (such as reduced size of cotyledons, leaves, flowers, and siliques) is present in any of the Gγ single and double mutants. Despite the considerable amount of phenotypic overlap between Gβ- and Gγ-deficient mutants, confirming the tight relationship between Gβ and Gγ subunits in plants, considering the significant differences reported here, we hypothesize the existence of new and as yet unknown elements in the heterotrimeric G protein signaling complex.

Heterotrimeric G proteins contain Gα, Gβ, and Gγ subunits and transduce signals from activated plasma membrane receptors to intracellular effectors (Gilman, 1987). Upon activation of the receptor, GDP bound to inactive Gα is exchanged for GTP, causing a conformational change that leads to activation with or without physical dissociation of the Gα subunit from the Gβγ complex (Rebois et al., 1997; Klein et al., 2000; Bunemann et al., 2003; Adjobo-Hermans et al., 2006; Digby et al., 2006). The activated subunits then transmit the signal to their specific effector molecules until intrinsic GTPase activity of the Gα subunit hydrolyzes the GTP molecule, thus returning Gα to its inactive state and sequestering Gβγ back to the inactive heterotrimer. Gβ and Gγ subunits form tightly bound dimers that work as functional units and can only be dissociated under strong denaturing conditions (Schmidt et al., 1992; Clapham and Neer, 1993; Gautam et al., 1998; McCudden et al., 2005).

In animal systems, G proteins mediate the signaling of over 800 receptors (G protein-coupled receptors; Pierce et al., 2002; Fredriksson et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2006). Multiple family members exist for each of the three subunits, and different combinatorial possibilities provide the required specificity for multitudinous G protein-based signaling pathways (Gautam et al., 1998; Balcueva et al., 2000; Wettschureck and Offermanns, 2005; Marrari et al., 2007). In open contrast, plants only contain one or two genes for each of the subunits (Ma et al., 1990; Poulsen et al., 1994; Weiss et al., 1994; Gotor et al., 1996; Iwasaki et al., 1997; Seo et al., 1997; Marsh and Kaufmann, 1999; Ando et al., 2000; Mason and Botella, 2000, 2001; Perroud et al., 2000; Kang et al., 2002; Hossain et al., 2003a, 2003b; Kato et al., 2004; Misra et al., 2007). In Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), a single Gα (Ma et al., 1990; Ma, 1994), a single Gβ (Weiss et al., 1994), and two Gγ (Mason and Botella, 2000, 2001) subunit genes have been identified.

Despite the fact that only two combinatorial possibilities are feasible for the heterotrimers in Arabidopsis, G proteins are involved in multiple processes (Assmann, 2004; Jones and Assmann, 2004; Perfus-Barbeoch et al., 2004). Recent genetic studies using Gα- and Gβ-deficient or -overproducing mutants have demonstrated the involvement of G proteins in abscisic acid (ABA) and brassinosteroid sensitivity during seed germination and early plant development (Ullah et al., 2002; Lapik and Kaufman, 2003; Chen et al., 2004, 2006; Pandey et al., 2006; Warpeha et al., 2006), stomatal regulation (Wang et al., 2001), d-Glc signaling (Huang et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2006), light perception (Okamoto et al., 2001; Warpeha et al., 2006, 2007), rosette leaf, flower, and silique development (Lease et al., 2001; Ullah et al., 2003), plant defense against necrotrophic fungi (Llorente et al., 2005; Trusov et al., 2006), and auxin signaling in roots (Ullah et al., 2003; Trusov et al., 2007). Similar functional multiplicity has been observed in rice (Oryza sativa; Ashikari et al., 1999; Fujisawa et al., 1999; Ueguchi-Tanaka et al., 2000; Suharsono et al., 2002; Komatsu et al., 2004; Oki et al., 2005).

In animals and fungi, the existence of a functional Gγ subunit is a compulsory prerequisite for the functioning of the entire heterotrimer, and lack of Gγ subunits results in the obliteration of both Gβγ- and Gα-mediated pathways (Gilman, 1987; Kisselev et al., 1994; Manahan et al., 2000; Krystofova and Borkovich, 2005; Myung et al., 2006). There is one notable exception to this rule: the human neurospecific Gβ5 subunit forms functional dimers with some members of the regulator of G protein signaling (RGS) subfamily C proteins instead of with conventional Gγ subunits (Snow et al., 1998; Sondek and Siderovski, 2001). Plant G proteins appear to behave similarly to their animal counterparts, and tight physical interaction between Gβ and each of the Gγ subunits has been demonstrated in vitro (Mason and Botella, 2000, 2001) and in vivo (Kato et al., 2004; Adjobo-Hermans et al., 2006). Moreover, it has been shown that Arabidopsis Gβ subunit localization on the plasma membrane requires a Gγ subunit (Obrdlik et al., 2000; Adjobo-Hermans et al., 2006). Evidence for functional interaction of the subunits was recently provided using overexpression of a truncated Gγ1 subunit lacking the isoprenylation motif (which is responsible for anchoring the βγ dimer to the membrane) and mutants lacking each of or both Gγ subunits (Chakravorty and Botella, 2007; Trusov et al., 2007). It has also been shown that different Gγ subunits confer specificity to the Gβγ dimer, with the Gβγ1 dimer mediating signal transduction events during plant defense against necrotrophic fungi, acropetal auxin signaling in roots, and osmotic stress regulation of seed germination, while Gβγ2 is involved in basipetal auxin signaling in roots and d-Glc sensing during germination (Trusov et al., 2007).

However, despite the above-mentioned similarities between plant and animal G proteins, a number of unusual properties observed in the plant subunits have led to suggestions that, in some cases, the animal paradigm may not necessarily hold true in plants. For instance, it was established that unlike animal subunits, Arabidopsis Gα and Gβγ are capable of tethering to the plasma membrane independently and do not rely on each other (Adjobo-Hermans et al., 2006; Zeng et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2008). It was also shown that the GTPase activity of the Arabidopsis Gα subunit is very low, leading to the hypothesis by some authors that Gα might be in the activated state by default (Willard and Siderovski, 2004; Johnston et al., 2007a; Temple and Jones, 2007). In addition, the interaction between Gα and the Gβγ dimer in rice has been reported to be relatively weak compared with that in animal systems (Kato et al., 2004), although formation of the heterotrimer in vivo has been demonstrated (Kato et al., 2004; Adjobo-Hermans et al., 2006). Recently, it was shown that in Arabidopsis both Gα and Gβ are associated with large macromolecular complexes of approximately 700 kD (Wang et al., 2008). Finally, Arabidopsis Gγ subunits are capable of being targeted to the plasma membrane in mutants lacking functional Gα and Gβ subunits (Zeng et al., 2007).

Here, we present data conflicting with the established heterotrimeric G protein model. We found that a number of phenotypic alterations observed in Gα- or Gβ-deficient mutants cannot be detected in mutants lacking Gγ1, Gγ2, or both Gγ subunits. Our results raise the possibility that Gγ subunits are not required for some Gα- and Gβ-mediated processes in Arabidopsis or that additional nonconventional Gγ subunits exist in this species.

RESULTS

The Expression Profiles of AGG1 and AGG2 in Reproductive Organs Do Not Match the AGB1 Expression Pattern

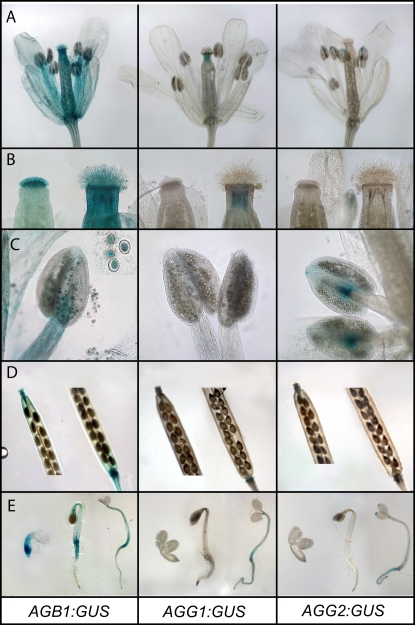

We previously reported that GUS staining patterns in transgenic Arabidopsis ecotype Columbia (Col-0) plants carrying promoter fusions of each of the AGG1 and AGG2 genes with the GUS reporter gene were tissue specific and that together they overlap AGB1 expression patterns in most plant tissues and developmental stages (Anderson and Botella, 2007; Trusov et al., 2007). Nevertheless, a number of small but important differences can also be observed, especially in reproductive tissues. Analysis of GUS expression in flowers and siliques revealed that AGB1 is moderately expressed in sepals and stamen filaments (Fig. 1A), with high expression found in stigma and pollen (Fig. 1, B and C). In siliques, GUS staining was observed at both ends, gradually disappearing toward the center (Fig. 1D). In AGG1:GUS plants, GUS expression was only detected in the stigma of mature flowers (Fig. 1, B and C), possibly correlating with pollination, while in siliques only the abscission zone showed staining (Fig. 1D). In AGG2:GUS transformants, GUS expression was evident in the apex of stamen filaments at a very early developmental stage and disappeared before the flower opened (Fig. 1C). No GUS staining was detected in siliques of AGG2:GUS plants. Discrepancies were also observed in germinating seeds, where distinct GUS staining in AGB1:GUS plants was observed much earlier (24 and 48 h after imbibition) than in AGG1:GUS or AGG2:GUS plants. However, expression in AGG1:GUS or AGG2:GUS increased to detectable levels and overlapped with AGB1 expression in 4-d-old seedlings (Fig. 1E), in agreement with a previous report (Trusov et al., 2007).

Figure 1.

AGB1, AGG1, and AGG2 expression patterns in flowers. Histochemical analysis of GUS expression in transgenic Arabidopsis plants carrying AGB1:GUS, AGG1:GUS, or AGG2:GUS fusions. A, Fully opened flowers. B, Stigma of young (unopened bud) and mature flowers. C, Anther, stamen filaments, and pollen. D, Green-stage siliques. E, Germinating seedlings at 24, 48, and 96 h after imbibition.

ABA Sensitivity of Gγ1- and Gγ2-Deficient Mutants in Germination

Heterotrimeric G protein involvement in different aspects of seed germination has been established by a number of studies (Ullah et al., 2002; Lapik and Kaufman, 2003; Chen et al., 2004, 2006; Pandey et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2007; Warpeha et al., 2007). Involvement of the heterotrimeric G protein signaling components GPA1, AGB1, GCR1, and RGS1 in ABA inhibition of seed germination is well documented (Ullah et al., 2002; Chen et al., 2004, 2006; Pandey et al., 2006). It was recently proposed that a second putative G protein-coupled receptor (GCR2) is a plasma membrane receptor for ABA (Liu et al., 2007); however, these results have been challenged (Gao et al., 2007; Johnston et al., 2007b; Illingworth et al., 2008).

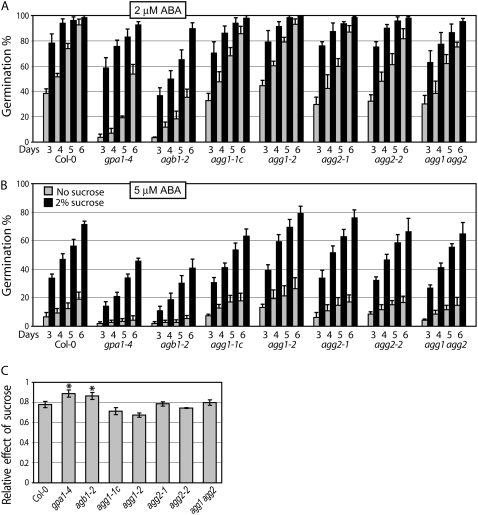

Roles for the Arabidopsis Gγ subunits, AGG1 and AGG2, in d-Glc and osmotic sensing during germination were recently reported (Trusov et al., 2007), but no data are available at present on their involvement in ABA sensing. Therefore, we compared the responses of Gα-, Gβ-, and Gγ-deficient mutants to ABA-mediated inhibition of germination (Fig. 2). We analyzed germination rates for seven different seed lots for each genotype (stored in an identical environment for approximately 1 month after harvest) under a number of experimental conditions. Each lot was tested at least twice. In all tests, all genotypes showed 100% germination on control medium (no ABA added) by day 3 after light exposure (data not shown). In accordance with previous reports showing hypersensitivity of Gα- and Gβ-deficient mutants to ABA during germination (Pandey et al., 2006), gpa1-4 and agb1-2 mutants showed enhanced ABA-mediated inhibition of germination compared with the wild type (Fig. 2, A and B). In contrast, four independent single Gγ-deficient mutants, agg1-1c, agg1-2, agg2-1, and agg2-2, as well as the double agg1 agg2 mutant showed levels of ABA sensitivity similar to wild-type plants and in one case (agg1-2 in 5 μm ABA) even showed hyposensitivity (P < 0.05; Fig. 2, A and B). In some isolated experiments, Gγ1- or Gγ2-deficient mutants showed either decreased or slightly increased ABA sensitivity compared with the wild type, but the responses never reached the hypersensitivity levels displayed by Gβ-deficient mutants. Figure 2, A and B, shows germination rates for the wild type and all mutants in a representative experiment. The differences in ABA sensitivity between gpa1-4 and agb1-2 mutants and all of the other genotypes analyzed (the wild type and Gγ-deficient mutants) were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Sensitivity to ABA-induced inhibition of seed germination in G protein complex mutants. A and B, Seeds from matched seed lots were surface sterilized and plated on 0.5× Murashige and Skoog medium plates in the presence of 2 μm (A) or 5 μm (B) ABA. Plates were transferred to 100 μmol m−2 s−1 light and 23°C. Germination was recorded at 3, 4, 5, and 6 d after transfer of the plates under light and expressed as a percentage of total number of seeds. The experiment was repeated three times, and data were averaged (n > 100 for each experiment). The error bars represent se. C, Rescue effect of Suc on germination inhibited by 5 μm ABA. Error bars indicate se values obtained from four measurements. Asterisks indicate values statistically significantly different from the wild type (P < 0.05).

It is known that high sugar concentration inhibits germination, while low amounts of Suc or Glc can rescue ABA-mediated inhibition of germination (Garciarrubio et al., 1997; Price et al., 2003). We analyzed germination rates on ABA-containing medium in the presence or absence of 2% Suc. Suc increased the germination of all genotypes at the two ABA concentrations assayed (Fig. 2, A and B), although, due to the complexity of the figure, it is difficult to visualize and compare the effects of Suc in the different genotypes. One useful way to visualize differences in behavior is to plot the relative effect of Suc on germination inhibition by ABA (Fig. 2C). Of the two ABA concentrations studied, only one (5 μm ABA) is amenable to this type of analysis, since in these specific experimental conditions, the percentage of germinated seeds showed a linear increase during the studied period (3–6 d after induction). In contrast, using 2 μm ABA, almost 100% germination was observed on days 5 to 6 for most genotypes. This allowed us to calculate the “rescue” effect of Suc as the relative increase in germination [e = (s − n)/s, where s is the percentage of germinated seeds on Suc-containing plates and n is the percentage of germinated seeds on plates without Suc] and average it for the four time points. Both gpa1-4 and agb1-2 mutants showed statistically significantly higher values than the remaining genotypes (P < 0.05), although absolute germination levels remained significantly (P < 0.05) lower for these genotypes than for all others.

Gγ-Deficient Mutants Do Not Display the agb1-2 Deetiolated Phenotype in Darkness

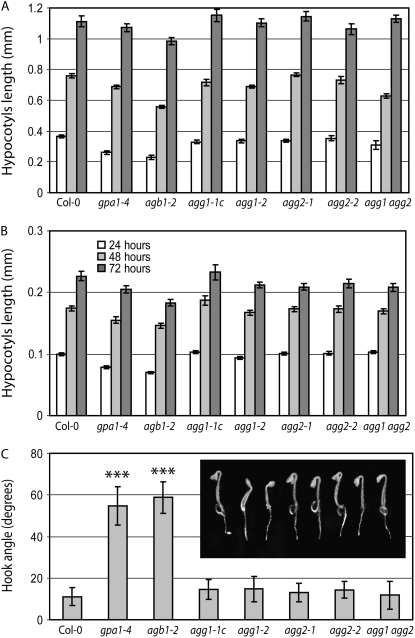

Partially deetiolated seedlings of Gα- and Gβ-deficient mutants have short hypocotyls with visibly increased girth and a characteristic open hook (Ullah et al., 2001, 2003; Wang et al., 2006). We analyzed hypocotyl elongation rate and hook development in darkness as well as light inhibition of hypocotyl elongation in gpa1-4, agb1-2, agg1-1c, agg1-2, agg2-1, agg2-2, and agg1 agg2 mutants as well as in the wild type. To ensure synchronized germination, all seeds were stratified for 5 d and induced to germinate under 150 μmol m−2 s−1 continuous light during 24 h. Afterward, plates with seeds were placed vertically either in a dark cabinet or under continuous light (90 μmol m−2 s−1) for 24, 48, and 72 h.

Figure 3, A and B, shows hypocotyl elongation dynamics of all mutant genotypes and the wild type grown in darkness and light, respectively. In agreement with previous reports (Ullah et al., 2001, 2003), hypocotyl elongation rates for Gα- and Gβ-deficient mutants (gpa1-4 and agb1-2) in darkness were lower compared with those for the wild type, with statistically significant differences after 24 and 48 h (P < 0.01 and P < 0.05, respectively). Under light, gpa1-4 and agb1-2 hypocotyls were significantly shorter than wild-type hypocotyls at all three time points (at least P < 0.05). In open contrast to the behavior of gpa1-4 and agb1-2 mutants, hypocotyl elongation in either dark or light conditions in each of the individual Gγ1- or Gγ2-deficient mutants or the double agg1 agg2 mutant was not statistically different from that in the wild type.

Figure 3.

Seedling development of G protein complex mutants grown in darkness or under light. A and B, Hypocotyl elongation rates of the wild type and the mutants at 24, 48, and 72 h after germination in darkness (A) or under 90 μmol m−2 s−1 light (B). Error bars indicate se. At least 20 seedlings were measured. C, Degree of hook opening in dark-grown wild-type and mutant seedlings measured approximately 24 h after germination. se values indicated by error bars are based on a minimum of 20 seedlings. Closed hooks were treated as having zero degree of opening. Triple asterisks indicate values statistically significantly different from the wild type (P < 0.001). The inset shows representative seedlings in order from left to right: Col-0, gpa1-4, agb1-2, agg1-1c, agg1-2, agg2-1, agg2-2, and agg1 agg2.

When the hook angle was measured after 24 h of dark incubation, gpa1-4 and agb1-2 mutants showed the typical “open-hook” phenotype described previously (Ullah et al., 2003; Fig. 2C). In contrast, all of the single Gγ-deficient mutants as well as the double agg1 agg2 mutant showed a wild-type phenotype clearly different from those of gpa1-4 and agb1-2.

None of the Morphological Alterations of Aerial Organs Observed in Gα- and Gβ-Deficient Mutants Is Present in Gγ-Deficient Mutants

Phenotypic analyses of Gα- and Gβ-deficient mutants have revealed a number of developmental and morphological abnormalities (Ullah et al., 2003). In order to determine whether Gγ-deficient mutants showed similar traits, we compared the wild type, gpa1-4, agb1-2, agg1-1c, agg1-2, agg2-1, agg-2-2, and agg1 agg2 grown under “standard” conditions as specified in “Materials and Methods.” Quantitative analysis of a number of morphological characteristics was carried out at defined growth stages (Boyes et al., 2001) during development (Table I; Fig. 4). Mean values of these traits in the mutant lines were analyzed for significant deviation from the corresponding values in the wild type by pair-wise, two-sample Student's t test. Unless stated otherwise, the mean values were derived from analysis of at least 30 plants grown in a checkerboard pattern.

Table I.

Morphological characterization of wild-type and mutant plants with altered heterotrimeric G proteins

*, P < 0.05. **, P < 0.01. ***, P < 0.001.

| Characteristic | Stage | Col-0 | gpa1-4 | agb1-2 | agg1-1c | agg1-2 | agg2-1 | agg2-2 | agg1 agg2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cotyledons (mm) | 1.0 | 6.7 ± 0.1 | 7.5 ± 0.1*** | 5.5 ± 0.1*** | 6.9 ± 0.2 | 6.5 ± 0.1 | 6.9 ± 0.1 | 6.6 ± 0.1 | 6.9 ± 0.2 |

| Rosette/leaf | |||||||||

| Length-width ratio | 3.90 | 1.8 ± 0.07 | 1.3 ± 0.05*** | 1.2 ± 0.04*** | 1.9 ± 0.07 | 1.8 ± 0.06 | 1.8 ± 0.08 | 1.8 ± 0.09 | 1.7 ± 0.12 |

| Petiole length (mm) | 3.90 | 9.6 ± 0.4 | 10.8 ± 0.3** | 6.7 ± 0.3*** | 9.3 ± 0.3 | 9.4 ± 0.4 | 8.9 ± 0.5 | 9.7 ± 0.3 | 8.8 ± 0.4 |

| Crinkly surface | 3.90 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Rosette diameter (mm) | 3.90 | 41.3 ± 1.1 | 43.0 ± 1.3 | 29.2 ± 1.2*** | 44.5 ± 1.0 | 41.4 ± 1.2 | 43.6 ± 1.0 | 43.9 ± 1.3 | 40.8 ± 1.8 |

| Inflorescence/flowers | |||||||||

| Buds are visible (day) | 5.10 | 22.7 ± 1.1 | 23.1 ± 1.3 | 24.9 ± 0.9* | 18.3 ± 1.5* | 19.3 ± 0.8* | 22.4 ± 1.1 | 21.9 ± 1.3 | 19.8 ± 0.7* |

| Length (cm) | 6.90 | 33.6 ± 0.6 | 30.1 ± 1.6 | 26.6 ± 1.3** | 32.2 ± 1.4 | 31.2 ± 1.2 | 32.3 ± 0.8 | 31.2 ± 1.1 | 32.3 ± 1.8 |

| No. of branches | 6.90 | 3.4 ± 0.4 | 3.5 ± 0.6 | 2.4 ± 0.5* | 3.1 ± 0.5 | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 3.5 ± 0.6 | 3.4 ± 0.5 | 3.1 ± 0.5 |

| No. of open flowers | 6.50 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 3.4 ± 0.3 | 6.4 ± 1.6** | 3.2 ± 0.6 | 2.9 ± 0.4 | 2.9 ± 0.6 | 3.1 ± 0.3 | 3.5 ± 0.4 |

| Flower diameter (mm) | 6.50 | 4.0 ± 0.3 | 3.5 ± 0.1* | 3.3 ± 0.2* | 4.1 ± 0.1 | 4.2 ± 0.1 | 4.4 ± 0.2 | 4.3 ± 0.2 | 4.0 ± 0.1 |

| Silique | |||||||||

| Length (mm) | 6.90 | 13.8 ± 0.3 | 12.7 ± 0.3* | 10.6 ± 0.2*** | 13.9 ± 0.4 | 13.7 ± 0.4 | 14.1 ± 0.5 | 13.8 ± 0.3 | 13.2 ± 0.3 |

| Width (mm) | 6.90 | 0.73 ± 0.02 | 0.82 ± 0.03** | 0.93 ± 0.03*** | 0.72 ± 0.02 | 0.70 ± 0.02 | 0.72 ± 0.02 | 0.71 ± 0.02 | 0.72 ± 0.02 |

| Blunt tip | 6.90 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Peduncle length (mm) | 6.90 | 7.8 ± 0.3 | 13.2 ± 0.5*** | 9.9 ± 0.3* | 7.7 ± 0.3 | 8.2 ± 0.4 | 8.1 ± 0.3 | 7.9 ± 0.3 | 8.1 ± 0.3 |

| No. of seeds | 8.00 | 51.6 ± 1.3 | 44.0 ± 1.2** | 39.6 ± 0.9*** | 55.3 ± 1.0 | 51.0 ± 1.1 | 50.0 ± 2.5 | 53.3 ± 1.5 | 49.3 ± 1.8 |

| No. of siliques (per cm) | 9.70 | 0.88 ± 0.02 | 0.93 ± 0.03 | 1.13 ± 0.02*** | 0.95 ± 0.02 | 0.81 ± 0.02 | 0.81 ± 0.01 | 0.93 ± 0.02 | 0.94 ± 0.04 |

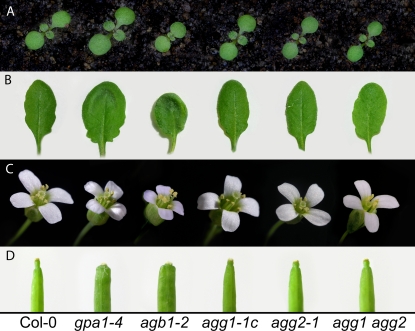

Figure 4.

Comparison of characteristic morphological traits in the wild type and gpa1-4, agb1-2, and Gγ mutants. A, Seven-day-old soil-grown seedlings. B, Average rosette leaves from a 30-d-old plant. C, Fully open mature flowers. D, Fully expanded siliques. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

Differences between agb1-2 and wild-type plants become apparent from a very early stage of development. Smaller and rounder cotyledons of agb1-2 mutants are apparent as early as 7 d after germination (Fig. 4A). The shape of the gpa1-4 cotyledons is very similar to that of wild-type cotyledons at this stage, although they are larger (Fig. 4A). In contrast, all of the single agg1-1c, agg1-2, agg2-1, and agg2-2 mutants as well as the double agg1 agg2 mutant are indistinguishable from the wild type at this developmental stage (Fig. 4A). Measurements of at least 50 seedlings of each genotype revealed that these visible differences between agb1-2 or gpa1-4 and the wild type are statistically significant (P < 0.001), while all Gγ-deficient mutants were indeed similar to the wild type (Table I). Rosette diameter measured at the inflorescence emergence stage was smaller in agb1-2 mutants (P < 0.001), partly due to the shorter size of the petioles (P < 0.001; Table I). The shorter petiole can be observed very early in Gβ-deficient mutants, giving a distinctive appearance caused by the cotyledons being very close to the hypocotyl (Fig. 4A). The rosette leaves of gpa1-4 and agb1-2 mutants have a characteristic crinkled surface and rounder appearance compared with those of the wild type (Fig. 4B). The ratios between leaf length and width in Gα- and Gβ-deficient mutants were significantly lower than in the wild type (P < 0.001; Table I). In contrast, neither the individual Gγ-deficient mutants nor the double agg1 agg2 mutant showed any statistically significant differences from the wild type for any of the above-mentioned traits: rosette diameter, leaf appearance, petiole size, and leaf length-width ratio.

Inflorescence emergence, defined by the appearance of flower buds, occurs approximately 2 d earlier in agg1-1c, agg1-2, and double agg1 agg2 mutants than in the wild type and gpa1-4, agg2-1, and agg2-2 mutants. The agb1-2 mutants showed delayed flowering, with inflorescence emergence occurring 2 d later than in the wild type (Table I). Despite the delay in inflorescence emergence (P < 0.05), the first agb1-2 flower opened at the same time as for the wild type, gpa1-4, and Gγ2-deficient mutants (data not shown). The final inflorescence height was noticeably lower in agb1-2 (P < 0.01), while all other mutants were similar in height to the wild type. Apical dominance is known to be regulated by basipetal auxin flow from the apical meristem (Jones, 1998; Dun et al., 2006; Leyser, 2006). Attenuation of auxin signaling by Gβ and both Gγ subunits has been established previously in roots (Ullah et al., 2003; Trusov et al., 2007). In the floral stem, our data showed increased apical dominance in agb1 mutants, as evidenced by a decreased number of branches, which is consistent with previous reports (Ullah et al., 2003). In contrast, all of the Gγ-deficient mutants showed a wild-type floral stem branching pattern. Contrary to a previous report (Ullah et al., 2003), we found that the number of open flowers at the midflowering stage was higher in agb1-2 plants (P < 0.01) compared with all other genotypes analyzed (Table I). Flowers were significantly smaller in agb1-2 and gpa1-4 mutants, while all Gγ-deficient mutants had flowers of similar size compared with the wild type (Table I; Fig. 4C). Even though we measured only the diameter of the fully open flower, sepal size was also affected in agb1-2 and gpa1-4 mutants, as can be seen in Figure 4C.

Alteration of the silique shape was first described for the agb1-1 mutant (Lease et al., 2001), and similar observations were made for agb1-2 (Ullah et al., 2003). Our measurements of agb1-2 concur with previous reports showing shorter and wider siliques (P < 0.001), with the characteristic blunt (flat) tips (Table I; Fig. 4D). Similarly to agb1-2, the gpa1-4 mutants produced shorter (although to a lesser extent) and wider siliques, with the characteristic blunt tip. Curiously, these results differ from those reported by Ullah et al. (2003), who analyzed two different Gα-deficient mutants, gpa1-1 and gpa1-2, and found their siliques to be slightly longer than wild-type siliques and having a wild-type tip shape. It is noteworthy that gpa1-1 and gpa1-2 mutants were obtained in the Wassilewskija (Ws) ecotype, while gpa1-4 (as well as another Gα-deficient mutant, gpa1-3) is in the Col-0 background. To analyze the effects of growth conditions or ecotype in silique development, we simultaneously grew gpa1-1, gpa1-2, gpa1-3, and gpa1-4 mutants and corresponding wild-type plants. Interestingly, siliques of gpa1-1 and gpa1-2 were indeed slightly longer than those of the Ws wild type, with “normal” acute tips, as described by Ullah et al. (2003), while both gpa1-3 and gpa1-4 siliques were shorter than those in the Col-0 wild type, and both had blunt tips (Table II). This observation is quite important, as it demonstrates that some effects of GPA1 deficiency are dependent on the genetic background and are not necessarily universal, even within the same species. Siliques in all Gγ-deficient mutants showed wild-type characteristics.

Table II.

Silique morphology of gpa1 mutants and corresponding wild-type control plants

*, P < 0.05. ***, P < 0.001.

| Characteristic | Col-0 | gpa1-3 | gpa1-4 | Ws | gpa1-1 | gpa1-2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length (mm) | 13.8 ± 0.3 | 12.4 ± 0.4* | 12.7 ± 0.3* | 13.1 ± 0.4 | 13.9 ± 0.4 | 14.1 ± 0.5* |

| Blunt tip | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Peduncle length (mm) | 7.8 ± 0.3 | 13.0 ± 0.5*** | 13.2 ± 0.3*** | 8.3 ± 0.4 | 16.2 ± 0.7*** | 15.4 ± 0.5*** |

In contrast to all other aerial organs, in which the knockout of AGB1 results in a reduced size, the silique peduncle was longer in agb1-2 mutants (Table I), and this trait was even more pronounced in gpa1-4 plants (P < 0.001). As has been the case with most of the morphological traits studied here, all Gγ-deficient mutants showed wild-type peduncle length (Table I). It is worth mentioning that, even though Gα-deficient mutants showed ecotype-dependent behavior for silique length and tip shape, the peduncles of gpa1-1, gpa1-2, gpa1-3, and gpa1-4 were almost twice as long as those of the relevant Ws or Col-0 wild-type control plants (P < 0.001; Table II). Importantly, peduncle length values presented here were obtained from the first two to three (lowest) siliques per plant, as peduncle length decreases gradually in size toward the top of the inflorescence. Nevertheless, the described trends were conserved along the entire inflorescence (data not shown). The number of seeds per silique was calculated using three siliques per plant and averaged for 10 plants per genotype. Siliques of agb1-2 and gpa1-4 mutants contained fewer seeds than wild-type controls (P < 0.001 and P < 0.01, respectively), while none of the Gγ-deficient mutants showed statistically significant difference from the wild type. The shorter inflorescence and higher number of siliques present in agb1-2 mutant plants resulted in a highly statistically significant difference in the density of siliques (number of siliques per centimeter of inflorescence), while Gα- and all Gγ-deficient mutants were similar to the wild type (Table I).

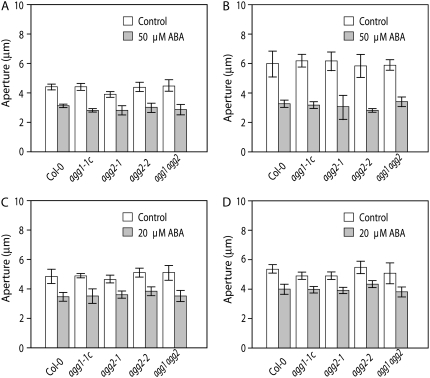

Guard Cells of Gγ-Deficient Mutants Show Wild-Type Responses to ABA

ABA is a well-studied phytohormone in guard cell signaling and is an important component of many stress responses in plants. In Arabidopsis, Gα-deficient mutants show alterations in a number of guard cell responses, such as hyposensitivity to ABA inhibition of stomatal opening and reduced ABA responsiveness of guard cell inward K+ channels (Wang et al., 2001; Coursol et al., 2003; Mishra et al., 2006). Our recent studies (L.M. Fan, unpublished data) show that Gβ-deficient mutants show the same alterations in guard cell ABA responses as observed for Gα-deficient mutants. Therefore, we assessed both ABA inhibition of light-induced stomatal opening and the ABA promotion of stomatal closure in Gγ-deficient plants. In agg1-1c, agg2-1, and agg2-2 single mutants, stomatal responses to 50 μm ABA were not statistically different from those of the wild type. A wild-type ABA response was also observed in the double agg1 agg2 mutant (Fig. 5, A and B). To ensure that a subtle alteration in ABA sensitivity was not overlooked in these experiments, the assays were repeated with a lower concentration of ABA (20 μm). As shown in Figure 5, C and D, stomatal aperture responses of the Gγ-deficient single and double mutants at this lower ABA concentration still remained indistinguishable from those of wild-type plants.

Figure 5.

ABA regulates stomatal movements similarly in Col and agg1-1c, agg2-1, agg2-2, and agg1 agg2. A, ABA (50 μm) inhibition of light-induced stomatal opening in Col, agg1-1c, agg2-1, agg2-2, and agg1 agg2. Data shown are means ± se from three replicates with n > 150 stomata for each experiment. B, ABA (50 μm) induction of stomatal closure in Col, agg1-1c, agg2-1, agg2-2, and agg1 agg2. Data shown are means ± se from three replicates with n > 150 stomata for each experiment. C, ABA (20 μm) inhibition of light-induced stomatal opening in Col, agg1-1c, agg2-1, agg2-2, and agg1 agg2. Data shown are means ± se from three replicates with n > 150 stomata for each experiment. D, ABA (20 μm) induction of stomatal closure in Col, agg1-1c, agg2-1, agg2-2, and agg1 agg2. Data shown are means ± se from three replicates with n > 150 stomata for each experiment.

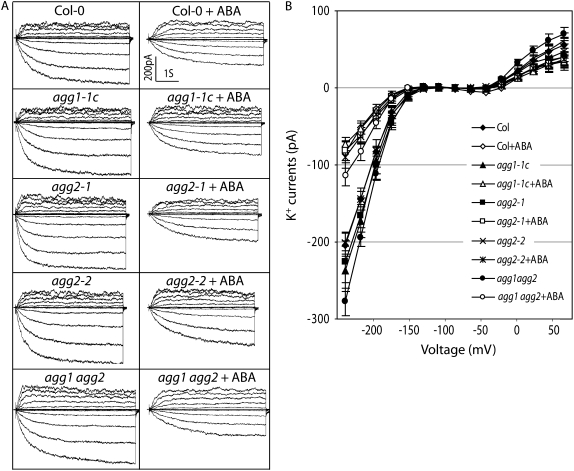

Many intracellular events contribute to the final outcome of an alteration in stomatal aperture. One well-defined aspect of the ABA inhibition of stomatal opening is inhibition of the K+ channels that mediate K+ uptake. To assess a more restricted ABA signaling pathway in guard cells, we used the electrophysiological technique of patch clamping to evaluate the ABA responsiveness of inward K+ currents. Gα- and Gβ-deficient mutants lack ABA inhibition of inward K+ currents (Wang et al., 2001; Coursol et al., 2003; L.M. Fan, unpublished data). By contrast, as shown in Figure 6, ABA inhibited the inward K+ currents of all of the Gγ-deficient single and double mutants to the same extent as was observed for wild-type guard cells. As has been reported previously (Wang et al., 2001; Becker et al., 2003), no ABA regulation of the outward K+ channels that mediate K+ efflux during stomatal closure was observed in wild-type Arabidopsis plants, and the same absence of an ABA effect was observed in Gα- and Gβ-deficient mutants (Wang et al., 2001; Coursol et al., 2003; L.M. Fan, unpublished data) as well as in all of the Gγ-deficient mutants (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

ABA regulates K+ currents similarly in guard cells of Col, agg1-1c, agg2-1, agg2-2, and agg1 agg2. A, Typical whole cell recordings of guard cell K+ currents with or without 50 μm ABA. Time and voltage scales shown in the top right panel apply to all panels. B, Current/voltage relationship (mean ± se) of time-activated whole cell K+ currents as illustrated in A. Number of guard cells was as follows: Col (11), Col + ABA (13), agg1-1c (10), agg1-1c + ABA (10), agg2-1 (eight), agg2-1 + ABA (16), agg2-2 (six), agg2-2 + ABA (seven), agg1 agg2 double mutant (16), and agg1 agg2 double mutant + ABA (17).

DISCUSSION

In the “canonical” model of heterotrimeric G protein signal transduction, activity of the Gβ subunit relies heavily on its binding to the Gγ subunit and subsequent membrane localization (Casey, 1995; Marrari et al., 2007). In plants, as in animals and fungi, the Gβ subunit of the heterotrimeric G protein requires interaction with a Gγ subunit for plasma membrane localization (Adjobo-Hermans et al., 2006; Zeng et al., 2007). In fact, both canonical Arabidopsis Gγ subunits were shown to be prenylated and localized to the plasma membrane (Adjobo-Hermans et al., 2006; Zeng et al., 2007). Also similar to animals, plant Gβ subunits are tightly bound to Gγ subunits, as shown in vitro (Mason and Botella, 2000, 2001) and in vivo (Kato et al., 2004; Adjobo-Hermans et al., 2006). Moreover, overexpression of a mutated AGG1 lacking the isoprenylation motif resulted in a phenotype that resembles that of Gβ-deficient mutants (Chakravorty and Botella, 2007). These facts compel us to hypothesize that in plants, as in animals, the βγ subunits act as a functional monomer. Therefore, Arabidopsis plants lacking either or both of the two known Gγ subunits (AGG1 or AGG2) should display phenotypes that totally or partially overlap those observed in mutants lacking AGB1. Furthermore, a double AGG1 AGG2 knockout is expected to be identical to the AGB1-deficient mutants in all respects. Indeed, this is the case in many instances, and we previously reported that lateral root formation, resistance to necrotrophic pathogens, and germination on 6% Glc are similarly altered in Gβ- and Gγ-deficient mutants (Trusov et al., 2007). Additionally, the expression patterns of AGG1 and AGG2 resembled AGB1 expression in most plant tissues (Trusov et al., 2007). On the other hand, the unique ability of the plant Gγ subunits to localize to the plasma membrane independently of Gβ (Adjobo-Hermans et al., 2006; Zeng et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2008) raises the possibility that in Arabidopsis Gβ-lacking mutants, free Gγ subunits could be involved in abnormal interactions. However, in many cases, this remote possibility could be ruled out by comparing Gβ-deficient mutants with Gα-deficient mutants possessing Gβγ dimers and not free Gγ subunits.

Here, we show that there are considerable discrepancies between the behavior of Gβ- and Gγ-deficient mutants, including the double agg1 agg2 mutant. AGB1 gene expression patterns in reproductive organs do not match AGG1, AGG2, or their combination. Hypocotyl elongation, both in darkness and under light, as well as hook development are altered in the Gβ-deficient mutant but not in any of the single Gγ-deficient mutants or in the double agg1 agg2 mutant. Furthermore, agb1-2 was hypersensitive to ABA during germination, while all Gγ-deficient mutants displayed wild-type sensitivity. Striking discrepancies were observed in the morphological and developmental phenotypic characterization of the mutants. It is remarkable that none of the aerial morphological traits for which the Gβ-deficient mutants show statistically significant differences from the wild type can be observed in the different Gγ-deficient mutants. The only instance in which Gγ1-deficient mutants, and the double agg1 agg2 mutant, show statistically significant differences from the wild-type controls is in flowering time; however, this effect was opposite to that observed in the Gβ-deficient mutant (Table I). Finally, in gpa1 (Wang et al., 2001; Coursol et al., 2003; Mishra et al., 2006) and agb1 (L.M. Fan, unpublished data), stomatal opening (but not stomatal closure) exhibits hyposensitivity to inhibition by ABA. In contrast, no ABA hyposensitivity of either ABA inhibition of stomatal opening or ABA promotion of stomatal closure was observed in any of the single Gγ-deficient mutants or the double agg1 agg2 mutant. Stomatal aperture responses result from a complex web of cellular signaling events that regulate multiple effectors (Li et al., 2006). Therefore, we also assessed one particularly well-defined subcellular event: ABA inhibition of inward K+ channels in guard cells (Blatt, 1990; Schwartz et al., 1994). In Gα- and Gβ-deficient lines, the response of inward K+ currents to ABA is abrogated (Wang et al., 2001; Coursol et al., 2003; L.M. Fan, unpublished data). However, in all of the Gγ-deficient mutants, guard cell K+ channel regulation by ABA was present at the same magnitude as in the wild type. Taken as a whole, our results demonstrate that the absence of the Gγ subunits does not completely phenocopy the lack of the Gβ subunit.

To explain the observed discrepancies, two not necessarily exclusive hypotheses could be proposed. The first is that additional Gγ subunits exist in Arabidopsis, which could possibly be expressed in reproductive organs to explain the expression discrepancies observed between AGB1 and the two known Gγ subunit genes, AGG1 and AGG2. Although exhaustive search of the fully sequenced Arabidopsis genome did not reveal any additional canonical Gγ subunits, these subunits display poor sequence conservation; therefore, the presence of atypical subunits cannot be discarded. This hypothesis allows retention of the heterotrimeric G protein dogma, developed mainly for mammalian systems, which states that all subunits are interdependent and required for proper signaling of the heterotrimer (Gilman, 1987).

A second hypothesis predicts some functional autonomy of the G protein subunits in plants, consistent with several recent observations. In animals, interdependence of Gα subunits and the corresponding Gβγ dimers for correct subcellular localization has been established (Takida and Wedegaertner, 2003), while in plants, the subunits do not depend on each other for plasma membrane targeting to the same extent (Adjobo-Hermans et al., 2006; Zeng et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2008). Moreover, both Arabidopsis Gγ subunits localized to the plasma membrane in Gα- and Gβ-deficient mutants (Zeng et al., 2007). Other unusual properties of the plant G protein complex recently led Temple and Jones (2007) to suggest that the plant heterotrimer is lagging behind in evolutionary terms from its animal counterparts. This antiquity could allow some functional autonomy for the individual subunits, since it is logical to propose that the heterotrimer most probably originated from three initially independent proteins. It is possible, therefore, that in some processes, plant Gα and Gβ subunits might act independently from each other and from Gγ subunits. Notably, some Gγ-dependent traits, such as susceptibility to necrotrophic fungi, methyl jasmonate sensitivity during root elongation and seed germination, and lateral root number, were altered in an opposite way in gpa1-4 compared with agb1-2 (Trusov et al., 2006, 2007). At the same time, many traits reported here, including ABA sensitivity in seed germination and stomatal regulation, floral organ shape, and hypocotyl elongation in darkness, which were similarly altered in gpa1-4 and agb1-2 mutants, were not altered in Gγ mutants. This could imply that Gα and Gβ, but not always Gγ, are part of an as yet uncharacterized complex, which governs those traits. Interestingly, in rice, all individual heterotrimeric G protein subunits were found as a part of 400-kD multiprotein complexes, but a fraction of the Gβγ dimers were also found not to be associated with those complexes (Kato et al., 2004). In Arabidopsis, membrane-associated 400-kD protein complexes were reported for the ERECTA receptor-like kinase (Shpak et al., 2003), and knockouts of ERECTA and ERECTA-like genes display similar phenotypes to Gα- and/or Gβ-deficient mutants in a number of traits (Lease et al., 2001; Shpak et al., 2004) as well as increased susceptibility to necrotrophic pathogens (Llorente et al., 2005), suggesting that G proteins could be an integral part of those complexes. Moreover, during the preparation of this article, it was reported that in Arabidopsis roughly 30% of the native Gα and all of the overexpressed cyan fluorescent protein (CFP)-Gβ are associated with large (approximately 700 kD) multiprotein complexes found in the plasma membrane fraction (Wang et al., 2008). Unfortunately, no information on Gγ-containing complexes was provided for either of the Gγ subunits (Wang et al., 2008).

The question arises whether plant Gβ can act independently of Gγ, as has already been described for Gβ5 in animal systems. The mammalian Gβ5 subunit can form functional dimers with a number of RGS proteins that contain a “Gγ-like motif” known as the GGL domain, precluding formation of the canonical dimer Gβ5γ (Snow et al., 1998; Witherow et al., 2000; Sondek and Siderovski, 2001; Witherow and Slepak, 2003; Willars, 2006). There are no known GGL domain-containing plant proteins; reports about plant GGL domain proteins, however, are currently available. In addition, the WD40 propeller structure of the Gβ subunit allows interaction with multiple proteins, hence providing a scaffold for large protein assemblies. In Arabidopsis and tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum), the Gβ subunit was identified in plasma membrane Triton X-100-insoluble microdomains along with other signaling components, including kinases and small GTP-binding proteins (Peskan and Oelmuller, 2000; Peskan et al., 2000; Shahollari et al., 2004). Thus, it is not unlikely that Gβ could function independently from Gγ as an integral part of multiprotein complexes to mediate some processes while functioning as a Gβγ dimer in others. In this scenario, knockout of AGB1 would destroy both the Gβγ dimers and the hypothetical Gβ-containing complexes, while the absence of Gγ subunits would only obliterate signaling that was directly dependent on Gβγ dimers.

In both hypotheses, it is necessary to explain how Gβ can be targeted to the plasma membrane in the absence of both Gγ subunits. A hybrid CFP-AGB1 fusion protein showed diffuse localization in the cytoplasm unless coexpressed with either AGG1 or AGG2 subunits (Adjobo-Hermans et al., 2006). This study demonstrated sufficiency of the Gγ subunits for the plasma membrane localization of Gβ. However, since this study was based on high ectopic expression of the AGB1, AGG1, and AGG2 genes, it is possible that other proteins, or complexes, can also anchor Gβ to the plasma membrane under normal circumstances. In this respect, it will be interesting to determine whether AGB1 is membrane localized in the agg1 agg2 double mutant. Just as for all other known Gγ subunits, the ability of AGG1 and AGG2 to be targeted to the plasma membrane crucially relies on prenylation of the C-terminal CAAX motif (Zeng et al., 2007). In Arabidopsis, two prenylation enzymes, geranylgeranyltransferase I (PGGT-I) and farnesyltransferase (PFT), have been identified (Caldelari et al., 2001; Running et al., 2004). Interestingly, knockout of PFT results in ABA hypersensitivity and phenotype alterations similar to those observed in Gα- and Gβ-deficient mutants, while knockout of PGGT-I, which has been shown to prenylate both AGG1 and AGG2 subunits (Zeng et al., 2007), leads to wild-type phenotype and wild-type ABA sensitivity in seed germination (Johnson et al., 2005; Zeng et al., 2007). Taken together with the fact that knockout of both Gγ subunits does not completely phenocopy Gβ-deficient mutant phenotypes, these observations suggest that there are additional, probably farnesylated, proteins interacting with AGB1 in Arabidopsis. It is possible, therefore, that currently unknown Gγ subunits, GGL-containing RGSs, or some components of the multiprotein complexes described by Wang et al. (2008) can be prenylated by PFT and are able to target AGB1 to the plasma membrane. It is interesting that in rice, the Gγ subunit RGG2 lacks the C-terminal prenylation motif but nevertheless is detected in the plasma membrane fraction associated with Gβ (Kato et al., 2004).

CONCLUSION

Additional studies will prove or disprove the feasibility of the hypotheses described above. Nevertheless, whatever the result of those studies, our data unambiguously reveal that the variety of heterotrimeric G proteins in plants is not limited to the two canonical heterotrimers Gαβγ1 and Gαβγ2 found so far. This adds an additional level of complexity to the molecular mechanisms used by G proteins in plants and provides a new degree of functional selectivity to that reported previously for the two known heterotrimers (Trusov et al., 2007).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material

The Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) agg1-1c mutant allele of AGG1 (At3g63420), the agg2-1 mutant allele of AGG2 (At3g22942), the double mutant agg1 agg2, and the agb1-2 mutant were described previously (Ullah et al., 2003; Trusov et al., 2007). New alleles agg1-2 and agg2-2 (both in the Col-0 background) were produced as T-DNA mutants by GαBI-Kat (Rosso et al., 2003). agg1-2 seeds were obtained from GαBI-Kat (accession no. 736A08), while agg2-2 lines were obtained from the Nottingham Arabidopsis Science Centre (accession no. N375172). For each new line, homozygous plants were selected using a three-primer PCR approach. The exact position of the T-DNA insertion was determined by amplifying and sequencing a genomic DNA fragment between the T-DNA end and the 3′ end of the gene in the chromosome. Absence of full-length AGG2 mRNA for agg2-2 was confirmed by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR (data not shown). In agg1-2, the insert is located in the promoter region, and full-size AGG1 mRNA was detected in the mutant. However, northern analysis revealed significant down-regulation in AGG1 mRNA levels in mutant plants (roughly 30% of the wild-type level; Supplemental Fig. S1).

Mutant Characterization

Mature plants were grown under a long-day (16 h of light/8 h of dark) and 23°C regimen for 6 weeks, and an additional 2 weeks were allowed for seed maturation. Morphological characteristics were measured at defined developmental stages as described elsewhere (Boyes et al., 2001). For destructive analysis (flower, silique, and leaf shape traits), plants were removed from the rest of the population randomly, dissected, and photographed if necessary.

Seed and Seedling Assays

All plates contained 0.5× Murashige and Skoog basal salts (PhytoTechnology Laboratories) and 0.8% agar. Stock solutions of ABA at the designated concentrations were added to autoclaved medium cooled to approximately 55°C. Since germination is extremely sensitive to the growth conditions experienced by the parental plant and to postharvest storage, all seed lots for seed and seedling assays were collected at the same time from plants grown simultaneously under the same conditions. The seeds were stored at 4°C in the dark. Seeds were dry sterilized by 3 h of incubation in a chamber filled with chlorine gas. Approximately 150 sterilized seeds of all tested lines were planted on the same petri dish with a designated treatment. After sowing, all seeds were stratified for at least 48 h at 4°C in darkness. Germination was defined as an obvious protrusion of the radicle.

For hypocotyl elongation assays, seeds were induced under continuous light (150 μmol m−2 s−1) for 24 h, then seedlings were grown on vertical plates for 1 to 3 d in a dark cabinet. The plates were photographed and hypocotyl length was measured.

Isolation of RNA and Transcript Analysis

Total RNA for northern analysis and RT-PCR was extracted as described previously (Trusov and Botella, 2006; Purnell and Botella, 2007). Probes for northern blots were labeled using a Rediprime II P32 radiolabeling kit (Amersham). Membranes were hybridized overnight in Church buffer (Church and Gilbert, 1984) at 65°C, washed twice in 0.1% SSC and 0.1% SDS solution as described (Petsch et al., 2005), and exposed to PhosphorImager plates for analysis (Molecular Dynamics). For RT-PCR, reverse transcriptions were carried out using the SuperScript III RT kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen) as described previously (Moyle et al., 2005). PCR amplifications were performed using GoTaq Green Master mix (Promega) in 35 cycles with the following parameters: 94°C for 30 s, 54°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min. The primers used for the AGG1 and AGG2 genes were described previously (Trusov et al., 2007).

Stomatal Aperture Experiments and Guard Cell Electrophysiology

Arabidopsis plants were grown in soil mix (Potting Mix; Miracle-Gro) in growth chambers with 8-/16-h light/dark and 22°C/20°C cycles. Fully expanded young leaves from 4-week-old plants were used for both stomatal aperture assays and guard cell protoplast isolation. All of the protocols for stomatal aperture assays and whole cell K+ current recordings from guard cells with and without ABA treatment were as described for previous analyses of Gα-deficient mutant plants (Wang et al., 2001; Coursol et al., 2003). For whole cell K+ current analysis, recordings obtained at 10 min after formation of the whole cell configuration were used and were analyzed as described (Coursol et al., 2003). Whole cell capacitances were used to normalize current amplitude (pA/pF) to avoid the influence of cell size. Data were compared with Student's t test, and results with P < 0.01 were considered significantly different.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Down-regulation of AGG1 gene expression in agg1-2 T-DNA mutants.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Mike Mason and Dr. David Chakravorty for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Australian Research Council (Discovery Grant nos. DP0344924 and DP0772145), the U.S. Department of Agriculture (grant no. 2006–35100–17254), and the National Science Foundation (grant no. MCB–0209694).

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantphysiol.org) is: José Ramón Botella (j.botella@uq.edu.au).

Some figures in this article are displayed in color online but in black and white in the print edition.

The online version of this article contains Web-only data.

Open Access articles can be viewed online without a subscription.

References

- Adjobo-Hermans MJW, Goedhart J, Gadella TWJ Jr (2006) Plant G protein heterotrimers require dual lipidation motifs of Gα and Gγ and do not dissociate upon activation. J Cell Sci 119 5087–5097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DJ, Botella JR (2007) Expression analysis and subcellular localization of the Arabidopsis thaliana G-protein β-subunit AGB1. Plant Cell Rep 26 1469–1480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando S, Takumi S, Ueda Y, Ueda T, Mori N, Nakamura C (2000) Nitcotiana tabacum cDNAs encoding α and β subunits of a heterotrimeric GTP-binding protein isolated from hairy root tissues. Genes Genet Syst 75 211–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashikari M, Wu JZ, Yano M, Sasaki T, Yoshimura A (1999) Rice gibberellin-insensitive dwarf mutant gene Dwarf 1 encodes the α-subunit of GTP-binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96 10284–10289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assmann SM (2004) Plant G proteins, phytohormones, and plasticity: three questions and a speculation. Sci STKE 2004 re20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balcueva EA, Wang Q, Hughes H, Kunsch C, Yu ZH, Robishaw JD (2000) Human G protein γ(11) and γ(14) subtypes define a new functional subclass. Exp Cell Res 257 310–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker D, Hoth S, Ache P, Wenkel S, Roelfsema MRG, Meyerhoff O, Hartung W, Hedrich R (2003) Regulation of the ABA-sensitive Arabidopsis potassium channel gene GORK in response to water stress. FEBS Lett 554 119–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatt MR (1990) Cellular signaling and volume control in stomatal movements in plants. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 16 221–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyes DC, Zayed AM, Ascenzi R, McCaskill AJ, Hoffman NE, Davis KR, Gorlach J (2001) Growth stage-based phenotypic analysis of Arabidopsis: a model for high throughput functional genomics in plants. Plant Cell 13 1499–1510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunemann M, Frank M, Lohse MJ (2003) Gi protein activation in intact cells involves subunit rearrangement rather than dissociation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100 16077–16082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldelari D, Sternberg H, Rodriguez-Concepcion M, Gruissem W, Yalovsky S (2001) Efficient prenylation by a plant geranylgeranyltransferase-I requires a functional CaaL box motif and a proximal polybasic domain. Plant Physiol 126 1416–1429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey PJ (1995) Protein lipidation in cell signaling. Science 268 221–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravorty D, Botella JR (2007) Over-expression of a truncated Arabidopsis thaliana heterotrimeric G protein γ subunit results in a phenotype similar to α and β subunit knockouts. Gene 393 163–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JG, Pandey S, Huang JR, Alonso JM, Ecker JR, Assmann SM, Jones AM (2004) GCR1 can act independently of heterotrimeric G-protein in response to brassinosteroids and gibberellins in Arabidopsis seed germination. Plant Physiol 135 907–915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Ji F, Xie H, Liang J, Zhang J (2006) The regulator of G-protein signaling proteins involved in sugar and abscisic acid signaling in Arabidopsis seed germination. Plant Physiol 140 302–310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church GM, Gilbert W (1984) Genomic sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 81 1991–1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapham D, Neer E (1993) New roles for G-protein βγ-dimers in transmembrane signalling. Nature 365 403–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coursol S, Fan LM, Stunff HL, Speigel S, Gilroy S, Assmann SM (2003) Sphignolipid signalling in Arabidopsis guard cells involves heterotrimeric G proteins. Nature 423 651–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Digby GJ, Lober RM, Sethi PR, Lambert NA (2006) Some G protein heterotrimers physically dissociate in living cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103 17789–17794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dun EA, Ferguson BJ, Beveridge CA (2006) Apical dominance and shoot branching: divergent opinions or divergent mechanisms? Plant Physiol 142 812–819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksson R, Lagerstrom MC, Lundin LG, Schioth HB (2003) The G-protein-coupled receptors in the human genome form five main families: phylogenetic analysis, paralogous groups, and fingerprints. Mol Pharmacol 63 1256–1272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisawa Y, Kato T, Ohki S, Ishikawa A, Kitano H, Sasaki T, Asahi T, Iwasaki Y (1999) Suppression of the heterotrimeric G protein causes abnormal morphology, including dwarfism, in rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96 7575–7580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao YJ, Zeng QN, Guo JJ, Cheng J, Ellis BE, Chen JG (2007) Genetic characterization reveals no role for the reported ABA receptor, GCR2, in ABA control of seed germination and early seedling development in Arabidopsis. Plant J 52 1001–1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garciarrubio A, Legaria JP, Covarrubias AA (1997) Abscisic acid inhibits germination of mature Arabidopsis seeds by limiting the availability of energy and nutrients. Planta 203 182–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam N, Downes GB, Yan K, Kisselev O (1998) The G-protein βγ complex. Cell Signal 10 447–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman AG (1987) G-proteins: transducers of receptor-generated signals. Annu Rev Biochem 56 615–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotor C, Lam E, Cejudo FJ, Romero LC (1996) Isolation and analysis of the soybean SGA2 gene (cDNA), encoding a new member of the plant G-protein family of signal transducers. Plant Mol Biol 32 1227–1234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain MS, Koba T, Harada K (2003. a) Cloning and characterization of a cDNA (TaGB1) encoding β subunit of heterotrimeric G-protein from common wheat cv. S615. Plant Biotechnol 20 153–158 [Google Scholar]

- Hossain MS, Koba T, Harada K (2003. b) Cloning and characterization of two full-length cDNAs, TaGA1 and TaGA2, encoding G-protein α subunits expressed differentially in wheat genome. Genes Genet Syst 78 127–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Taylor JP, Chen JG, Uhrig JF, Schnell DJ, Nakagawa T, Korth KL, Jones AM (2006) The plastid protein THYLAKOID FORMATION1 and the plasma membrane G-protein GPA1 interact in a novel sugar-signaling mechanism in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 18 1226–1238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illingworth CJR, Parkes KE, Snell CR, Mullineaux PM, Reynolds CA (2008) Criteria for confirming sequence periodicity identified by Fourier transform analysis: application to GCR2, a candidate plant GPCR. Biophys Chem 133 28–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki Y, Kato T, Kaidoh T, Ishikawa A, Asahi T (1997) Characterization of the putative α subunit of a heterotrimeric G protein in rice. Plant Mol Biol 34 563–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CD, Chary SN, Chernoff EA, Zeng Q, Running MP, Crowell DN (2005) Protein geranylgeranyltransferase I is involved in specific aspects of abscisic acid and auxin signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 139 722–733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston CA, Taylor JP, Gao Y, Kimple AJ, Grigston JC, Chen JG, Siderovski DP, Jones AM, Willard FS (2007. a) GTPase acceleration as the rate-limiting step in Arabidopsis G protein-coupled sugar signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104 17317–17322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston CA, Temple BR, Chen JG, Gao YJ, Moriyama EN, Jones AM, Siderovski DP, Willard FS (2007. b) Comment on “A G protein-coupled receptor is a plasma membrane receptor for the plant hormone abscisic acid”. Science 318 914c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AM (1998) Auxin transport: down and out and up again. Science 282 2201–2202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AM, Assmann SM (2004) Plants: the latest model system for G-protein research. EMBO Rep 5 572–578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang SG, Lee HJ, Park EH, Suh SG (2002) Molecular cloning and characterization of cDNAs encoding heterotrimeric G protein α and β subunits from potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Mol Cells 13 99–106 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato C, Mizutani T, Tamaki H, Kumagai H, Kamiya T, Hirobe A, Fujisawa Y, Kato H, Iwasaki Y (2004) Characterisation of heterotrimeric G protein complexes in rice plasma membrane. Plant J 38 320–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisselev OG, Ermolaeva MV, Gautam N (1994) A farnesylated domain in the G-protein γ-subunit is a specific determinant of receptor coupling. J Biol Chem 269 21399–21402 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein S, Reuveni H, Levitzki A (2000) Signal transduction by a nondissociable heterotrimeric yeast G protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97 3219–3223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu S, Yang G, Hayashi N, Kaku H, Umemura K, Iwasaki Y (2004) Alterations by a defect in a rice G protein α subunit in probenazole and pathogen-induced responses. Plant Cell Environ 27 947–957 [Google Scholar]

- Krystofova S, Borkovich KA (2005) The heterotrimeric G-protein subunits GNG-1 and GNB-1 form a Gβγ dimer required for normal female fertility, asexual development, and Gα protein levels in Neurospora crassa. Eukaryot Cell 4 365–378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapik YR, Kaufman LS (2003) The Arabidopsis cupin domain protein AtPirin1 interacts with the G protein α-subunit GPA1 and regulates seed germination and early seedling development. Plant Cell 15 1578–1590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lease KA, Wen J, Li J, Doke JT, Liscum E, Walker JC (2001) A mutant Arabidopsis heterotrimeric G-protein β subunit affects leaf, flower, and fruit development. Plant Cell 13 2631–2641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyser O (2006) Dynamic integration of auxin transport and signalling. Curr Biol 16 R424–R433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Assmann SM, Albert R (2006) Predicting essential components of signal transduction networks: a dynamic model of guard cell abscisic acid signaling. PLoS Biol 4 1732–1748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XG, Yue YL, Li B, Nie YL, Li W, Wu WH, Ma LG (2007) A G protein-coupled receptor is a plasma membrane receptor for the plant hormone abscisic acid. Science 315 1712–1716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorente F, Alonso-Blanco C, Sanchez-Rodriguez C, Jorda L, Molina A (2005) ERECTA receptor-like kinase and heterotrimeric G protein from Arabidopsis are required for resistance to the necrotrophic fungus Plectosphaerella cucumerina. Plant J 43 165–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H (1994) GTP-binding proteins in plants: new members of an old family. Plant Mol Biol 26 1611–1636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H, Yanofsky MF, Meyerowitz EM (1990) Molecular cloning and characterization of GPA1, a G protein α subunit gene from Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87 3821–3825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manahan CL, Patnana M, Blumer KJ, Linder ME (2000) Dual lipid modification motifs in Gα and Gγ subunits are required for full activity of the pheromone response pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell 11 957–968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrari Y, Crouthamel M, Irannejad R, Wedegaertner PB (2007) Assembly and trafficking of heterotrimeric G proteins. Biochemistry 46 7665–7677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh JF, Kaufmann LS (1999) Cloning and characterisation of PGA1 and PGA2: two G protein α-subunits from pea that promote growth in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Plant J 19 237–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason MG, Botella JR (2000) Completing the heterotrimer: isolation and characterization of an Arabidopsis thaliana G protein γ-subunit cDNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97 14784–14788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason MG, Botella JR (2001) Isolation of a novel G-protein γ-subunit from Arabidopsis thaliana and its interaction with Gβ. Biochim Biophys Acta 1520 147–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCudden CR, Hains MD, Kimple RJ, Siderovski DP, Willard FS (2005) G-protein signaling: back to the future. Cell Mol Life Sci 62 551–577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra G, Zhang WH, Deng F, Zhao J, Wang XM (2006) A bifurcating pathway directs abscisic acid effects on stomatal closure and opening in Arabidopsis. Science 312 264–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra S, Wu Y, Venkataraman G, Sopory SK, Tuteja N (2007) Heterotrimeric G-protein complex and G-protein-coupled receptor from a legume (Pisum sativum): role in salinity and heat stress and cross-talk with phospholipase C. Plant J 51 656–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyle R, Fairbairn DJ, Ripi J, Crowe M, Botella JR (2005) Developing pineapple fruit has a small transcriptome dominated by metallothionein. J Exp Bot 56 101–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myung CS, Lim WK, DeFilippo JM, Yasuda H, Neubig RR, Garrison JC (2006) Regions in the G protein γ subunit important for interaction with receptors and effectors. Mol Pharmacol 69 877–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obrdlik P, Neuhaus G, Merkle T (2000) Plant heterotrimeric G protein β subunit is associated with membranes via protein interactions involving coiled-coil formation. FEBS Lett 476 208–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto H, Matsui M, Deng XW (2001) Overexpression of the heterotrimeric G-protein α-subunit enhances phytochrome-mediated inhibition of hypocotyl elongation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 13 1639–1652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oki K, Fujisawa Y, Kato H, Iwasaki Y (2005) Study of the constitutively active form of the α subunit of rice heterotrimeric G proteins. Plant Cell Physiol 46 381–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey S, Chen J-G, Jones AM, Assmann SM (2006) G-protein complex mutants are hypersensitive to abscisic acid regulation of germination and postgermination development. Plant Physiol 141 243–256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Perfus-Barbeoch L, Jones AM, Assmann SM (2004) Plant heterotrimeric G protein function: insights from Arabidopsis and rice mutants. Curr Opin Plant Biol 7 719–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perroud PF, Diogon T, Crevecoeur M, Greppin H (2000) Molecular cloning, spatial and temporal characterization of spinach SOGA1 cDNA, encoding an α subunit of G protein. Gene 248 191–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peskan T, Oelmuller R (2000) Heterotrimeric G-protein β-subunit is localized in the plasma membrane and nuclei of tobacco leaves. Plant Mol Biol 42 915–922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peskan T, Westermann M, Oelmuller R (2000) Identification of low-density Triton X-100-insoluble plasma membrane microdomains in higher plants. Eur J Biochem 267 6989–6995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petsch KA, Mylne J, Botella JR (2005) Cosuppression of eukaryotic release factor 1-1 in Arabidopsis affects cell elongation and radial cell division. Plant Physiol 139 115–126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce KL, Premont RT, Lefkowitz RJ (2002) Seven-transmembrane receptors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 3 639–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulsen C, Mai XM, Borg S (1994) Lotus japonicus cDNA encoding an α-subunit of a heterotrimeric G protein. Plant Physiol 105 1453–1454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price J, Li TC, Kang SG, Na JK, Jang JC (2003) Mechanisms of glucose signaling during germination of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 132 1424–1438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purnell MP, Botella JR (2007) Tobacco isoenzyme 1 of NAD(H)-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase catabolizes glutamate in vivo. Plant Physiol 143 530–539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebois RV, Warner DR, Basi NS (1997) Does subunit dissociation necessarily accompany the activation of all heterotrimeric G proteins? Cell Signal 9 141–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosso MG, Li Y, Strizhov N, Reiss B, Dekker K, Weisshaar B (2003) An Arabidopsis thaliana T-DNA mutagenized population (GABI-Kat) for flanking sequence tag-based reverse genetics. Plant Mol Biol 53 247–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Running MP, Lavy M, Sternberg H, Galichet A, Gruissem W, Hake S, Ori N, Yalovsky S (2004) Enlarged meristems and delayed growth in plp mutants result from lack of CaaX prenyltransferases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101 7815–7820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt CJ, Thomas TC, Levine MA, Neer EJ (1992) Specificity of G protein β subunit and γ subunit interactions. J Biol Chem 267 13807–13810 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz A, Wu WH, Tucker EB, Assmann SM (1994) Inhibition of inward K+ channels and stomatal response by abscisic acid: an intracellular locus of phytohormone action. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91 4019–4023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo HS, Choi CH, Lee SY, Cho MJ, Bahk JD (1997) Biochemical characteristics of a rice (Oryza sativa L, IR36) G-protein α-subunit expressed in Escherichia coli. Biochem J 324 273–281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahollari B, Peskan-Berghofer T, Oelmuller R (2004) Receptor kinases with leucine-rich repeats are enriched in Triton X-100 insoluble plasma membrane microdomains from plants. Physiol Plant 122 397–403 [Google Scholar]

- Shpak ED, Berthiaume CT, Hill EJ, Torii KU (2004) Synergistic interaction of three ERECTA-family receptor-like kinases controls Arabidopsis organ growth and flower development by promoting cell proliferation. Development 131 1491–1501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shpak ED, Lakeman MB, Torii KU (2003) Dominant-negative receptor uncovers redundancy in the Arabidopsis ERECTA leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinase signaling pathway that regulates organ shape. Plant Cell 15 1095–1110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow BE, Krumins AM, Brothers GM, Lee SF, Wall MA, Chung S, Mangion J, Arya S, Gilman AG, Siderovski DP (1998) A G protein γ subunit-like domain shared between RGS11 and other RGS proteins specifies binding to Gβ5 subunits. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95 13307–13312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sondek J, Siderovski DP (2001) G γ-like (CGL) domains: new frontiers in G-protein signaling and β-propeller scaffolding. Biochem Pharmacol 61 1329–1337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suharsono U, Fujisawa Y, Kawasaki T, Iwasaki Y, Satoh H, Shimamoto K (2002) The heterotrimeric G protein α subunit acts upstream of the small GTPase Rac in disease resistance of rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99 13307–13312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takida S, Wedegaertner PB (2003) Heterotrimer formation, together with isoprenylation, is required for plasma membrane targeting of G βγ. J Biol Chem 278 17284–17290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple BRS, Jones AM (2007) The plant heterotrimeric G-protein complex. Annu Rev Plant Biol 58 249–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trusov Y, Botella JR (2006) Silencing of the ACC synthase gene ACACS2 causes delayed flowering in pineapple Ananas comosus (L.) Merr. J Exp Bot 57 3953–3960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trusov Y, Rookes JE, Chakravorty D, Armour D, Schenk PM, Botella JR (2006) Heterotrimeric G-proteins facilitate Arabidopsis resistance to necrotrophic pathogens and are involved in jasmonate signaling. Plant Physiol 140 210–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trusov Y, Rookes JE, Tilbrook K, Chakravorty D, Mason MG, Anderson D, Chen JG, Jones AM, Botella JR (2007) Heterotrimeric G protein γ subunits provide functional selectivity in Gβγ dimer signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19 1235–1250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueguchi-Tanaka M, Fujisawa Y, Kobayashi M, Ashikari M, Iwasaki Y, Kitano H, Matsuoka M (2000) Rice dwarf mutant d1, which is defective in the α subunit of the heterotrimeric G protein, affects gibberellin signal transduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97 11638–11643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullah H, Chen J-G, Temple B, Boyes DC, Alonso JM, Davis KR, Ecker JR, Jones AM (2003) The β-subunit of the Arabidopsis G protein negatively regulates auxin-induced cell division and affects multiple developmental processes. Plant Cell 15 393–409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullah H, Chen J-G, Wang S, Jones AM (2002) Role of a heterotrimeric G protein in regulation of Arabidopsis seed germination. Plant Physiol 129 897–907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullah H, Chen JG, Young JC, Im KH, Sussman MR, Jones AM (2001) Modulation of cell proliferation by heterotrimeric G protein in Arabidopsis. Science 292 2066–2069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HX, Weerasinghe RR, Perdue TD, Cakmakci NG, Taylor JP, Marzluff WF, Jones AM (2006) A Golgi-localized hexose transporter is involved in heterotrimeric G protein-mediated early development in Arabidopsis. Mol Biol Cell 17 4257–4269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Assmann SM, Fedoroff NV (2008) Characterization of the Arabidopsis heterotrimeric G protein. J Biol Chem (in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wang XQ, Ullah H, Jones AM, Assmann SM (2001) G protein regulation of ion channels and abscisic acid signaling in Arabidopsis guard cells. Science 292 2070–2072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warpeha KM, Lateef SS, Lapik Y, Anderson M, Lee BS, Kaufman LS (2006) G-protein-coupled receptor 1, G-protein G α-subunit 1, and prephenate dehydratase 1 are required for blue light-induced production of phenylalanine in etiolated Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 140 844–855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warpeha KM, Upadhyay S, Yeh J, Adamiak J, Hawkins SI, Lapik YR, Anderson MB, Kaufman LS (2007) The GCR1, GPA1, PRN1, NF-Y signal chain mediates both blue light and abscisic acid responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 143 1590–1600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss C, Garnaat C, Mukai K, Hu Y, Ma H (1994) Isolation of cDNAs encoding guanine nucleotide-binding protein β-subunit homologues from maize (ZGB1) and Arabidopsis (AGB1). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91 9554–9558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wettschureck N, Offermanns S (2005) Mammalian G proteins and their cell type specific functions. Physiol Rev 85 1159–1204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willard FS, Siderovski DP (2004) Purification and in vitro functional analysis of the Arabidopsis thaliana regulator of G-protein signaling-1. Methods Enzymol 389 320–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willars GB (2006) Mammalian RGS proteins: multifunctional regulators of cellular signalling. Semin Cell Dev Biol 17 363–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witherow DS, Slepak VZ (2003) A novel kind of G protein heterodimer: the G β5-RGS complex. Receptors Channels 9 205–212 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witherow DS, Wang Q, Levay K, Cabrera JL, Chen J, Willars GB, Slepak VZ (2000) Complexes of the G protein subunit G β5 with the regulators of G protein signaling RGS7 and RGS9. J Biol Chem 275 24872–24880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Q, Wang XJ, Running MP (2007) Dual lipid modification of Arabidopsis Gγ-subunits is required for efficient plasma membrane targeting. Plant Physiol 143 1119–1131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, DeVries ME, Skolnick J (2006) Structure modeling of all identified G protein-coupled receptors in the human genome. PLoS Comput Biol 2 88–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.