Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To identify factors associated with satisfaction with care for healthcare proxies (HCPs) of nursing home (NH) residents with advanced dementia.

DESIGN

Cross-sectional study.

SETTING

Thirteen NHs in Boston.

PARTICIPANTS

One hundred forty-eight NH residents aged 65 and older with advanced dementia and their formally designated HCPs.

MASUREMENTS

The dependent variable was HCPs’ score on the Satisfaction With Care at the End of Life in Dementia (SWC-EOLD) scale (range 10-40; higher scores indicate greater satisfaction). Resident characteristics analyzed as independent variables were demographic information, functional and cognitive status, comfort, tube feeding, and advance care planning. HCP characteristics were demographic information, health status, mood, advance care planning, and communication. Multivariate stepwise linear regression was used to identify factors independently associated with higher SWC-EOLD score.

RESULTS

The mean ages ± standard deviation of the 148 residents and HCPs were 85.0 ± 8.1 and 59.1 ± 11.7, respectively. The mean SWC-EOLD score was 31.0 ± 4.2. After multivariate adjustment, variables independently associated with greater satisfaction were more than 15 minutes discussing advance directives with a care provider at the time of NH admission (parameter estimate=2.39, 95% confidence interval (CI)=1.16-3.61, P<.001), greater resident comfort (parameter estimate=0.10, 95% CI=0.02-0.17, P=.01), care in a specialized dementia unit (parameter estimate=1.48, 95% CI=0.25-2.71, P=.02), and no feeding tube (parameter estimate=2.87, 95% CI=0.46-5.25, P 5.02).

CONCLUSION

Better communication, greater resident comfort, no tube feeding, and care in a specialized dementia unit are modifiable factors that may improve satisfaction with care in advanced dementia.

Keywords: dementia, palliative care, nursing home

The increasing prevalence of dementia in older Americans has led to efforts aimed at improving end-of-life care for this population. According to estimates from the 2000 U.S. Census, 4.5 million Americans have Alzheimer’s disease.1 Approximately 70% of persons with dementia will die in nursing homes (NHs).2 Thus, the provision of high-quality palliative care in the NH setting is essential.3-7

Although many caregivers feel that palliation is the appropriate goal of care in advanced dementia,8 earlier work has shown that the terminal care provided to persons with this condition is not adequate.3,9 For example, NH residents dying with dementia are less likely to have advance directives and more likely to undergo aggressive interventions near the end of life than those with terminal cancer.4 Furthermore, it has been suggested that promoting advance care planning may improve the comfort of the NH resident.4

A core aim of palliative care is to assure not only the well-being of the patient, but also that of the family.10,11 Emerging data suggest that the emotional distress of families does not decline when patients with dementia are institutionalized.12 Although the reason for this observation is not known, it is possible that dissatisfaction with NH care contributes to families’ stress. The specific determinants of family satisfaction with end-of-life dementia care in the NH setting have not been well studied. A better understanding of these determinants may enable nursing facilities to improve the quality of care provided to residents dying with dementia and their families.13

To address this gap in our knowledge, the purpose of this study was to identify factors associated with the satisfaction of family members with the care provided to persons with advanced dementia in the NH setting. To conduct this research, baseline data were used from an ongoing, prospective study of advanced dementia in the NH, the Choices, Attitudes, and Strategies for Care of Advanced Dementia at the End of Life (CASCADE) study.

The institutional review board at Hebrew Senior Life approved conduct of the study.

METHODS

Study Population

Subjects examined in this study consisted of dyads: NH residents with advanced dementia living in 13 Boston-area facilities and their formally designated healthcare proxies (HCPs). Subjects were recruited between February 2003 and April 2005 as part of the longitudinal CASCADE Study. Data used in this report were derived from the baseline assessments of the first 148 dyads recruited into the study. Participant facilities were required to have at least 60 beds and be located within a 60-mile radius of Boston.

To recruit a cohort with advanced dementia, the facilities’ Minimum Data Set (MDS) database was used to identify residents with a Cognitive Performance Score (CPS) of5 or 6 on their most recent MDS assessments, indicating severe to very severe cognitive impairment.14 A CPS score of 5 corresponds to a Mini-Mental State Examination score of 5.1 ± 5.3.14 Once identified, the charts of residents with a CPS of 5 or 6 were screened for full eligibility, which consisted of aged 60 and older, length of stay longer than 30 days, cognitive impairment due to dementia, Global Deterioration Scale (GDS) score of 7,15 and an appointed HCP who could communicate in English. If the diagnosis of dementia was ambiguous in the chart, the resident’s physician was contacted for clarification. Stage 7 of the GDS is characterized by very severe cognitive decline with minimal to no verbal communication, assistance needed to eat and toilet, incontinence of urine and stool, and loss of basic psychomotor skills (e.g., may have lost the ability to walk).15 Exclusion criteria included care in a subacute or short-term rehabilitative unit; cognitive impairment due to stroke, traumatic brain injury, tumor, or chronic psychiatric condition; and coma.

Data Collection and Variables

Resident data were obtained from review of their medical records, interview with their primary care nurses, and a brief clinical examination. All HCP data were obtained by self-report during 10-minute telephone interviews conducted by trained research assistants.

The dependent variable was the HCPs’ satisfaction with care as measured using the Satisfaction With Care at the End of Life in Dementia (SWC-EOLD) scale.16 The SWC-EOLD is a validated scale that quantifies satisfaction with care in advanced dementia during the prior 90 days. The SWC-EOLD has 10 items, each measured on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 4 as follows: strongly disagree, disagree, agree, and strongly agree. These items assess the HCP’s satisfaction with decision-making, medical and nursing care, and their understanding of the resident’s condition. The total SWC-EOLD score represents a summation of all 10 items (range 10-40), with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction.

Independent variables thought to possibly influence HCP satisfaction were selected for analysis from the resident assessments and HCP interviews a priori based on the literature and clinical experience.5-7,10,11,13,16-20 These factors included processes of care that could potentially affect HCP satisfaction (i.e., the outcome). Factors considered redundant with components of the SWC-EOLD were not considered as independent variables. Resident characteristics included variables in the following areas: demographic information, functional and cognitive status, comfort, tube feeding, and advance care planning. Demographic data obtained from the medical record included age, sex, race/ethnicity (white vs other), length of NH stay, and whether the resident was cared for in a specialized dementia unit. The resident’s primary care nurse provided functional status using the Bedford Alzheimer’s Nursing Severity Subscale (range 7-28, higher scores indicating greater functional disability).20 Nurses also quantified residents’ comfort using the Symptom Management at End of Life in Dementia (SM-EOLD) scale (range 0-45, higher scores indicating greater comfort).16 Cognitive disability was obtained from direct clinical examination of the resident using the Test for Severe Impairment (TSI) (range 0-24, lower scores indicating greater cognitive impairment).17 Whether the resident had a feeding tube was also ascertained. In terms of advance care planning, the presence in the record of a do-not-resus-citate (DNR) order, do-not-hospitalize (DNH) order, and living will was determined.

HCP independent variables in the following categories were examined: sociodemographic information, health status, mood, and advance care planning. HCP sociodemographics included age, sex, race (white vs other), relationship to the resident, current work status (full time vs other), years designated as HCP, level of education (>high school education vs other), primary language (English vs other), marital status (married/living with partner vs other), and time spent visiting resident (>7hours per week vs other).

HCP health status was assessed using the Medical Outcomes Study 12-item Short Form survey (SF-12) (physical and mental components, range 10-70, higher scores indicating better health).21 Mood was assessed using the K6, a validated and reliable 6-item instrument assessing depressive symptoms (range 0-24, higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms).22 With respect to advance care planning, HCPs were asked to rate the extent to which they agreed that comfort was the primary goal of care (strongly agree, agree, disagree, and strongly disagree). The responses to this question were dichotomized as strongly agree or agree versus other in the analyses. HCPs were asked to estimate how long they expected the resident to live (<6 months vs other). HCPs were also asked the following question: “Around the time of NH admission, how much time did a healthcare provider from the facility spend with you discussing advance care planning for directives such as DNR, DNH, use of intravenous fluids, etc.” The response categories were none, 1 to 5 minutes, 6 to 15 minutes, or longer than 15 minutes. All HCPs who did not respond “none” to this question were then asked, in an open-ended fashion, which provider discussed these issues with them. These providers were categorized as follows: physician, nurse providing direct care, social worker, nurse administrator (i.e., director of nursing, nurse manager), other administrator (i.e., director of admissions), or other (asked to specify). Finally, HCPs were asked whether a physician had counseled them about the resident’s prognosis.

Statistical Analysis

The outcome for all analyses was the SWC-EOLD scale, analyzed as a continuous variable. Descriptive statistics were conducted for all variables using frequencies for categorical variables and means for continuous variables. The statistical software SAS, version 8.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) was used for all analyses.

Bivariate analyses were conducted to examine the associations between each independent variable and the outcome (SWC-EOLD) using unadjusted linear regression. All variables associated with SWC-EOLD at a significance level of Po.10 in the bivariate analyses were entered into a multivariate model using stepwise linear regression to determine factors independently associated with SWC-EOLD.

RESULTS

Subject Characteristics

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the 148 residents and HCPs. Residents had a mean age of 85.0 ± 8.1, 87.8% werefemale, and 92.6% were white (data not shown). The mean length of stay in the NH was 1,402.3 ± 1,294.1 days, and 52.7% of residents lived in a special care dementia unit. The mean Bedford Alzheimer’s Nursing Severity Subscale score was 20.8 ± 2.7, indicating advanced functional disability. The mean SM-EOLD score was 36.1 ± 8.1. The residents had profound cognitive impairment, as demonstrated by a mean TSI score of 0.4 ± 1.3, with 21.0% of residents having a score TSI greater than 0. Ten residents (6.8%) had feeding tubes, 73 (49.3%) had a DNH order, and 19 (12.8%) had a living will. Because 96.6% had DNR orders, this variable was not included in the analysis.

Table 1. Characteristics of Nursing Home Residents with Advanced Dementia and Their Healthcare Proxies and Bivariate Associations with Greater Satisfaction with End-of-Life Care (N = 148).

| Characteristic | Value | P-value | Parameter Estimate (95% Confidence Interval) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resident | |||

| Demographic | |||

| Age, mean ± SD (range) | 85.0 ± 8.1 (60.0-103.0) | .25 | -0.05 (-0.13-0.037) |

| Female, % | 87.8 | .09 | 1.75 (-0.28-3.72) |

| Length of stay, days, mean ± SD (range) | 1,402.3 ± 1,294.1 (54.0-5,537.0) | .01 | 0.0006 (0.0001-0.001) |

| Lives in special care dementia unit, % | 52.7 | .005 | 1.91 (0.56-3.20) |

| Health status | |||

| Bedford Alzheimer’s Nursing Severity Subscale score, mean ± SD (range)* | 20.8 ± 2.7 (11.0-27.0) | .94 | -0.01 (-0.25-0.24) |

| Symptom Management at the End of Life in Dementia score, mean ± SD (range)† | 36.1 ± 8.1 (10.0-45.0) | .007 | 0.11 (0.03-0.19) |

| Test for Severe Impairment score >0, %‡ | 21.0 | .56 | 0.49 (-1.20-2.08) |

| Tube fed, % | 6.8 | .003 | -4.00 (-6.61-1.37) |

| Advance care planning | |||

| Do not hospitalize, % | 49.3 | .001 | 2.18 (0.87-3.48) |

| Living will, % | 12.8 | .09 | -1.71 (-3.72-0.28) |

| Healthcare proxy | |||

| Sociodemographic | |||

| Age, mean ± SD (range) | 59.1 ± 11.7 (32.0-92.0) | .18 | -0.04 (-0.10-0.02) |

| Female, % | 61.5 | .25 | -0.80 (-2.16-0.60) |

| White, % | 92.6 | .17 | 1.80 (-0.77-4.36) |

| Married/living with partner, % | 71.6 | .27 | 0.85 (-0.66-2.32) |

| Education >high school, % | 77.7 | .29 | 0.86 (-0.73-2.51) |

| English is primary language, % | 96.6 | .43 | 1.48 (-2.26-5.22) |

| Child of resident, % | 73.0 | .94 | -0.03 (-1.54-1.48) |

| Working full time, % | 46.0 | .41 | 0.56 (-0.77-1.92) |

| Years designated as proxy, mean ± SD (range) | 7.1 ± 5.4 (0.50-40.0) | .04 | 0.13 (0.01-0.26) |

| Visits resident >7 hours per week, % | 20.3 | .69 | -0.34 (-2.05-1.31) |

| Health status, mean ± SD (range) | |||

| Medical Outcomes Survey 12-Item Short Form§ | |||

| Physical component | 51.7 ± 9.2 (21.0-65.0) | .25 | 0.05 (-0.03-0.12) |

| Mental component | 51.4 ± 9.9 (10.3-67.1) | .06 | -0.06 (-0.01-0.13) |

| K6∥ | 2.5 ± 3.4 (10.0-45.0) | .53 | -0.07 (-0.27-0.12) |

| Advance care planning, % | |||

| Primary goal of care is comfort | 95.2 | .01 | 3.96 (0.83-7.08) |

| Feels resident has <6 months to live | 8.7 | .47 | 0.97 (-1.69-3.66) |

| Spent >15 minutes discussing advance directives with a care provider | 55.3 | <.001 | 2.35 (1.04-3.63) |

| Physician counseled about prognosis | 35.8 | .10 | 1.18 (-0.24-2.56) |

Possible score 7-28; higher scores indicate greater functional disability.

Possible score 0-45; higher scores indicate greater comfort.

Possible score 0-24; lower scores indicate greater cognitive impairment.

Possible score 10-70; higher scores indicate greater physical and mental health.

Depressive symptom scale, possible score 0-24; higher scores indicate more depressive symptoms.

SD = standard deviation.

The mean age ± standard deviation of HCPs was 59.1 ± 1.7; 61.5% were female. The majority of HCPs were white (92.6%), were married or living with a partner (71.6%), had more than a high school education (77.7%), and spoke English as their primary language (96.9%). The distribution of the HCP’s relationship to the resident was as follows: child 108, 73.0%; spouse 15, 10.1%; niece or nephew 12, 8.1%; sibling 5, 3.4%; grandchild 2, 1.4%; and others 6, 4.0%. Slightly fewer than half of the HCPs worked full time (46.0%). The mean time designated as HCP was 7.1 ± 5.4 years, and only 20.3% visited the resident for more than 7 hours per week. HCPs had a mean score of 51.7 ± 9.2 on the SF-12 physical component, indicating good physical health; 51.4 ± 9.9 on the SF-12 mental component, indicating good psychological health; and 2.5 ± 3.4 on the K6, indicating a low prevalence of depressive symptoms.

Most HCPs felt that the primary goal of care was to provide comfort to the dementia patient (95.2%). Only 8.7% of HCPs felt that the resident had less than 6 months to live. Twenty-two HCPs (14.9%) did not discuss advance directives with a care provider at the time of NH admission, 22 (14.9%) spent 1 to 5 minutes, 26 (17.5%) spent 6 to 15 minutes, and 78 (52.7%) spent longer than 15 minutes discussing these directives. Of the 126 HCPs who discussed these issues, many did so with more than one provider, distributed as follows: physician, 23 (18.2%); nurse providing direct care, 45 (35.7%); social worker, 95 (75.4%); nurse administrator, 21 (16.7%); other administrator, six (4.2%); and other, two (1.6%) (physical therapist and ombudsman). Provider type was not associated with whether advance directives were discussed for more than 15 minutes. Physicians had counseled 35.8% of HCPs about residents’ prognoses.

Factors Associated with Satisfaction with End-of-Life Care

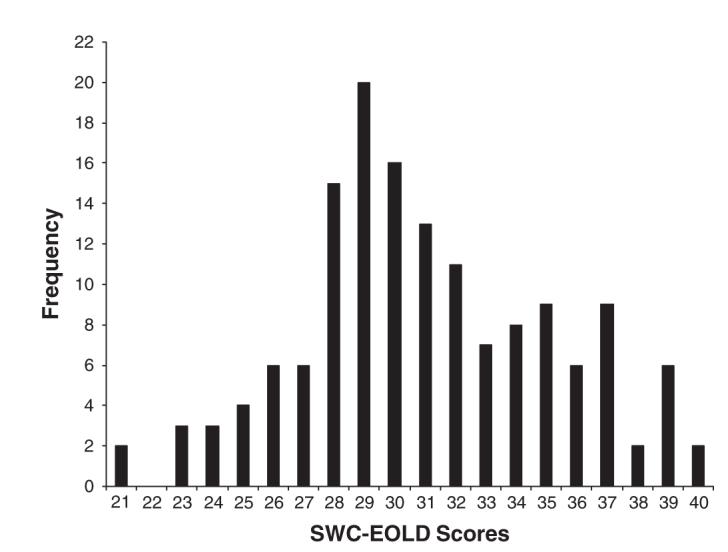

The mean score on the SWC-EOLD scale was 31.0 ± 4.2, which approximated a normal distribution (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of healthcare proxies’ satisfaction with end-of-life care (SWC-EOLD) scores (N=148).

Resident variables associated with a higher SWC-EOLD score (i.e., greater satisfaction) at a level of P<.10 in the bivariate analysis were (Table 1) female, longer length of stay, residing in a special-care dementia unit, higher SM-EOLD score (i.e., greater physical comfort), and the presence of a DNH order. Tube feeding was negatively correlated with higher satisfaction with care.

HCP variables associated with a higher SWC-EOLD score at P<.10 in the bivariate analysis were more years as designated HCP, having comfort as a primary goal of care, longer than 15 minutes discussing advance directives with a NH care provider, and having been counseled about prognosis. Items associated with lower SWC-EOLD scores (i.e., less satisfaction) included higher scores on the SF-12 mental component (i.e., better mental health) and having prolongation of life as a primary care goal.

In the final multivariate linear regression model, the variable most strongly associated with higher SWC-EOLD scores (greater satisfaction with care) (Table 2) was longer than 15 minutes discussing advance directives with a healthcare provider at the time of NH admission (parameter estimate=2.39, 95% confidence interval (CI)=1.16-3.61, P<.001). Other variables independently associated with greater satisfaction with care were higher SM-EOLD scores (i.e., greater resident comfort) (parameter estimate=0.10, 95% CI=0.02-0.17, P=.01), care in a specialized dementia unit (parameter estimate=1.48, 95% CI=0.25-2.71, P=.02), and the absence of a feeding tube (parameter estimate=2.87, 95% CI=0.46-5.25, P=.02). For each of these variables, the parameter estimates in Table 2 represent the unit change in the SWC-EOLD for every unit change of the independent variable being analyzed. For example, for each unit increase in resident comfort analyzed using the SM-EOLD, HCP satisfaction increased by 0.10 points on the SWC-EOLD scale.

Table 2. Multivariate Analysis of Resident and Healthcare Proxy Characteristics with Greater Satisfaction with End-of-Life Care (N = 148).

| Characteristic | P-value | Parameter Estimate (95% Confidence Interval) |

|---|---|---|

| Proxy spent >15 minutes with physician planning advance care | <.001 | 2.39 (1.16-3.61) |

| Symptom management at the end of life in dementia* | .01 | 0.10 (0.02-0.17) |

| Lives in special care dementia unit | .02 | 1.48 (0.25-2.71) |

| Resident is not tube fed | .02 | 2.87 (0.46-5.25) |

Possible range 0-45; higher scores indicate greater comfort.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that satisfaction with end-of-life care among HCPs of NH residents with advanced dementia varies and is associated with factors related to communication, health services, and residents’ comfort and medical interventions. Time spent by a care provider discussing advance directives with the HCP at the time of NH admission was the strongest determinant of satisfaction. Greater HCP satisfaction with care was also more likely for residents who experienced less discomfort, resided in a special care dementia unit, and were not tube fed. These findings suggest that there are potentially modifiab2le factors that could be targeted to improve end-of-life care for people with advanced dementia in the NH setting.

The finding that more time spent discussing advance directives with a healthcare provider increased HCP satisfaction with care supports previous research indicating that advance care planning is of primary importance for families of terminally ill patients.6,10 It is possible that the amount of time spent discussing specific directives may be a marker for overall better communication and shared decision-making between HCPs and healthcare professionals. Moreover, greater attention to eliciting care preferences may reduce HCP distress related to entrusting the care of their loved one to NH providers, particularly at the difficult transition point of NH admission.

A second finding, related to healthcare delivery, indicates greater satisfaction of HCPs of residents with advanced dementia who were residing in a special care unit. Although earlier research supports this finding,7,13 the specific component of a unit specializing in dementia care that promotes greater satisfaction is not well understood. Special care units employ professionals with specific training in advanced dementia, who presumably have a focused interest in managing persons with this condition and their families. Thus, it follows that HCPs who perceive that their loved one is receiving services individualized to their specific needs would report a greater satisfaction with care.

Two resident characteristics were related to HCP satisfaction in the current study: physical comfort and tube feeding. Current literature points to adequate and effective pain management at the end of life as a high priority for patients with terminal illnesses and their families,6,11,23 but to the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is first the study to demonstrate a direct relationship between greater comfort of persons with advanced dementia (as ascertained by a nurse) and higher HCP satisfaction with care. It is reasonable to assume that HCPs would be less satisfied with care if their loved ones with advanced dementia were experiencing greater suffering.

Research has shown that feeding tubes have no demonstrable benefits for patients with end-stage dementia, yet the use of this intervention is still common in U.S. NHs.24-28 A prior study showed that, in hindsight, the majority of proxies of tube-fed NH residents with advanced dementia regret their decision to initiate tube feeding.29 Therefore, no prior research has examined the influence of tube feeding on families’ satisfaction with overall care. The current study suggests that the HCPs of tube-fed residents with advanced dementia are less satisfied than HCPs of those without feeding tubes. Further study is needed to determine whether this observation relates to the occurrence of adverse sequelae of tube feeding or inherent characteristics of the HCPs of tube-fed residents that lead to greater dissatisfaction.

This study has limitations that deserve comment. First, the study participants were almost all white. Prior work has shown that racial and ethnic factors are important determinants of end-of-life care in dementia.26 Thus, these findings may not be generalizable to other racial or ethnic backgrounds. Second, detailed information was not available about the advance care planning process or tube feeding decisions. Thus, the specific reasons why less time spent discussing advance directives and tube feeding use were associated with less satisfaction cannot be completely elucidated. Third, HCPs may not have precisely remembered how long they spent discussing advance directives with care providers at the time of NH admission, although the association (i.e., parameter estimate) between the duration of these discussions and satisfaction with care did not change when length of stay was added to the model. Moreover, recall bias is likely to be nondifferential with respect to satisfaction with care. Finally, it was not possible to determine the precise component of a special care dementia unit that confers greater HCP satisfaction.

Because NHs are a major site of palliative care for patients with advanced dementia,5 addressing family satisfaction is crucial to providing high-quality end-of-life care. The current study suggests that more time spent discussing advance directives, improving patient comfort, less use of feeding tubes, and management in special care dementia units are potential areas to target future interventions to improve satisfaction with end-of-life care in advanced dementia.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial Disclosure: Supported by American Federation for Aging Research/Hartford Foundation Medical Student Scholarship (SEE), National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant T32 AG023480 (SEE), NIH-National Institute on Aging (NIA) Grant R01 AG024091 (SLM), and NIH-NIA Grant P50 AG05134 Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center Grant (SLM).

Footnotes

Sponsor’s Role: The funding sources for this study played no role in the design or conduct of the study;collection, analysis, interpretation or preparation of thedata; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Bienias JL, et al. Alzheimer's disease in the U.S. pop- ulation: Prevalence estimates using the 2000 census. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1119–1122. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.8.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Miller SC, et al. A national study of the location of death for older persons with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:299–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shega JW, Levin A, Hougham GW, et al. Palliative Excellence in Alzheimer Care Efforts (PEACE): A program description. J Palliat Med. 2003;6:315–320. doi: 10.1089/109662103764978641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Hamel MB. Dying with advanced dementia in the nursing home. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:321–326. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell SL, Morris JN, Park PS, et al. Terminal care for persons with advanced dementia in the nursing home and home care settings. J Palliat Med. 2004;7:808–816. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2004.7.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, et al. Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. JAMA. 2004;291:88–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tornatore JB, Grant LA. Burden among family caregivers of persons with Alzheimer's disease in nursing homes. Gerontologist. 2002;42:497–506. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.4.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luchins DJ, Hanrahan P. What is appropriate health care for end-stage de- mentia? J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41:25–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb05943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sachs GA, Shega JW, Cox-Hayley D. Barriers to excellent end-of-life care for patients with dementia. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:1057–1063. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30329.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albinsson L, Strang P. Differences in supporting families of dementia patients and cancer patients: A palliative perspective. Palliat Med. 2003;17:359–367. doi: 10.1191/0269216303pm669oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teno JM, Casey VA, Welch LC, et al. Patient-focused, family-centered end-of- life medical care: Views of the guidelines and bereaved family members. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22:738–751. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00335-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schulz R, Belle SH, Czaja SJ, et al. Long-term care placement of dementia patients and caregiver health and well-being. JAMA. 2004;292:961–967. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.8.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tornatore JB, Grant LA. Family caregiver satisfaction with the nursing home after placement of a relative with dementia. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2004;59B:S80–S88. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.2.s80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morris JN, Fries BE, Mehr DR, et al. MDS cognitive performance scale. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1994;49A:M174–M182. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.4.m174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reisberg B, Ferris SH, De Leon MJ, et al. The global deterioration scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139:1136–1139. doi: 10.1176/ajp.139.9.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Volicer L, Hurley AC, Blasi ZV. Scales for evaluation of end-of-life care in dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2001;15:194–200. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200110000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albert M, Cohen C. The test for severe impairment. An instrument for the assessment of patients with severe cognitive dysfunction. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:449–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb02009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martire LM, Stephens MAP, Atienza AA. The interplay of work and caregiv- ing: Relationships between role satisfaction, role involvement, and caregivers' well-being. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1997;52B:S279–S289. doi: 10.1093/geronb/52b.5.s279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teno JM, Landrum K, Lynn J. Defining and measuring outcomes in end-stage dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1997;11:25–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Volicer L, Hurley AC, Lathi DC, et al. Measurement of severity in advanced alzheimer's disease. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M223–M226. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.5.m223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller S. A 12-item short form health survey: Construc- tion of scales and preliminary test of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psy- chol Med. 2002;32:959–976. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larson JS, Larson KK. Evaluating end-of-life care from the perspective of the patient's family. Eval Health Prof. 2002;25:143–151. doi: 10.1177/01678702025002001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finucane TE, Christmas C, Travis K. Tube feeding in patients with advanced dementia: A review of the evidence. JAMA. 1999;282:1365–1370. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.14.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gillick M. Rethinking the role of tube feeding in patients with advanced de- mentia. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:206–210. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001203420312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitchell SL, Buchanan JL, Littlehale S, et al. Tube-feeding versus hand-feeding nursing home residents with advanced dementia: A cost comparison. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2003;4:27–33. doi: 10.1097/01.JAM.0000043421.46230.0E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Roy J, et al. Clinical and organizational factors asso- ciated with feeding tube use among nursing home residents with advanced cognitive impairment. JAMA. 2003;290:73–80. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shega JW, Hougham GW, Stocking CB, et al. Barriers to limiting the practice of feeding tube placement in advanced dementia. J Palliat Med. 2003;6:885–893. doi: 10.1089/109662103322654767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitchell SL, Lawson FME, Berkowitz RA, et al. A cross national survey of decision for long-term tube-feeding in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:391–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]