Abstract

Treatment of human cervical epithelial CaSki cells with ATP or with the diacylglyceride sn-1,2-dioctanoyl diglyceride (diC8) induced a staurosporine-sensitive transient increase, followed by a late decrease, in tight-junctional resistance (RTJ). CaSki cells express two immunoreactive forms of occludin, 65 and 50 kDa. Treatments with ATP and diC8 decreased the density of the 65-kDa form and increased the density of the 50-kDa form. ATP also decreased threonine phosphorylation of the 65-kDa form and increased threonine phosphorylation of the 50-kDa form and tyrosine phosphorylation of the 65- and 50-kDa forms. Staurosporine decreased acutely threonine and tyrosine phosphorylation of the two isoforms and in cells pretreated with staurosporine ATP increased acutely the density of the 65-kDa form and threonine phosphorylation of the 65-kDa form. Treatment with N-acetyl-leucinyl-leucinyl-norleucinal increased the densities of the 65- and 50-kDa forms. Pretreatment with N-acetyl-leucinyl-leucinyl-norleucinal attenuated the late decreases in RTJ induced by ATP and diC8 and the decrease in the 65-kDa and increase in the 50-kDa forms induced by ATP. Correlation analyses showed that high levels of RTJ correlated with the 65-kDa form, whereas low levels of RTJ correlated negatively with the 65-kDa form and positively with the 50-kDa form. The results suggest that in CaSki cells 1) occludin determines gating of the tight junctions, 2) changes in occludin phosphorylation status and composition regulate the RTJ, 3) protein kinase-C-mediated, threonine dephosphorylation of the 65-kDa occludin form increases the resistance of assembled tight junctions, 4) the early stage of tight junction disassembly involves calpain-mediated breakdown of occludin 65-kDa form to the 50-kDa form, and 5) increased levels of the 50-kDa form interfere with occludin gating of the tight junctions.

The main function of epithelia that line the female lower genital tract is to control secretion of mucus. The cervical-vaginal mucus is important for women’s health and human reproduction, and abnormal secretion of mucus can lead to disease states and cause infertility (1). The major component of the cervical-vaginal mucus is plasma-derived fluid that is generated from the blood and is secreted into the lumen by transudation through the paracellular space (2). Secretion of the fluid is controlled predominantly by the epithelial cells, and movement of water and solutes through the epithelial paracellular space is restricted by the tight junctions (3).

Gating of the paracellular space is controlled by transmembrane junctional proteins, such as junctional-associated molecules (4), claudins (5–8), and occludin (9, 10). Of the three groups of transmembrane junctional proteins, human cervical epithelial cells express claudin-4 and occludin (11). In cervical cells, occludin is present as two main immunoreactive forms, 65 and 50 kDa (11), and cellular levels of occludin, but not claudin-4, can be modulated by estrogen treatment. It was previously shown that estrogen decreases expression of the 65-kDa form and increases expression of the 50-kDa form in a dose- and time-related manner (11). Moreover, changes in occludin correlated with decreases in tight junctional resistance (RTJ) (11–13). In contrast, treatment with estrogen had no significant effect on claudin-4 (11), suggesting that in cervical cells occludin plays an important role in gating the tight junctional space and controlling the RTJ.

Previous studies that looked into regulation of the RTJ used the paradigm that tight junctions are rigid structures, built like a fence, and changes in RTJ were viewed in terms of assembly/disassembly of the tight-junctional complex (reviewed in Ref. 14). Recent studies in human cervical epithelial cells have shown acute and reversible modulation of RTJ that is not the result of assembly/disassembly of tight junctions but possibly the result of conformational changes of assembled tight junctions (15). One of the objectives of the present study was to understand the role that occludin could have in the modulation of assembled tight junctions. Another objective was to understand the source and biological significance of the occludin 50-kDa form. Most previous studies described occludin as a 65-kDa form, and expression of higher molecular mass forms depended on phosphorylation status of the protein (16). Two studies described occludin splice variants, termed occludin 1B (a longer form of occludin with a unique N-terminal sequence of 56 amino acids) (17), and occludin TM4− (lacking the fourth transmembrane domain) (Ref. 18), but both were larger in size than the 50-kDa form described in cervical cells (11). One study showed that occludin obtained from the Triton X-100-insoluble fraction of MDCK cells migrated as two bands of 65 and 50 kDa (19), but the authors did not elaborate on their finding.

In the present study, we tested the possibility that the 50-kDa form is a product of posttranslational modification of the native occludin 65-kDa form. The results suggest that in cervical cells occludin determines the gating of the tight junctions, and changes in occludin phosphorylation status and composition regulate the RTJ. Protein kinase C-mediated threonine dephosphorylation of the 65-kDa occludin form can increase acutely the resistance of assembled tight junctions. In contrast, the early stages of tight junction disassembly involve augmented calpain-mediated breakdown of the occludin 65-kDa form to a 50-kDa form. Our results further suggest that increased levels of the 50-kDa form interfere with gating of the tight junctions by the 65-kDa occludin form.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture techniques

The experiments used CaSki cells, which are a stable line of transformed cervical epithelial cells previously characterized (20). CaSki cells were grown and subcultured in culture dishes in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 8% fetal calf serum, 0.2% NaHCO3, nonessential amino acids, L-glutamine (2 mM), penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 mg/ml), and gentamycin (50 μg/ml) at 37 C in a 95% O2/5% CO2 humidified incubator and routinely tested for mycoplasma (20). Electrophysiological experiments were done on cells plated on Anocell (Anocell-10) filters (Oxon, UK, obtained through Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO), which are ceramic-base filters with a pore size of 0.02 μm width and 50 μm depth. Filters were coated on their upper (luminal) surface with 3–5 μg/cm2 collagen type IV as previously described (11, 20). Cells were plated on the upper surface of the filter at 3–5 × 105 cells/cm2, and within 12–24 h after plating, cultures usually become confluent and cells form intercellular connections, including tight junctions (2). Electrophysiological experiments used d 3–4 cultures as described (2). All treatments involved adding drugs to both the luminal and subluminal solutions.

Measurements of transepithelial electrical resistance (RTE)

Changes in transepithelial resistance were determined according to the Ussing-Zerahn model of fluid transepithelial transport (21, 22). This model predicts that the overall permeability properties of secretory epithelia are determined by the intercellular (paracellular) route and that the paracellular permeability is determined by the resistance of the intercellular tight junctions (RTJ) and by the resistance of the lateral intercellular space (RLIS) in series. The tight junctions confer high resistance to the movement of water and solutes, because of the occlusion of the intercellular space by the tight junctional complexes. In contrast, RLIS is considered a low-resistive element, and it is determined by the proximity of the plasma membranes of neighboring cells and by the length of the intercellular space from the tight junctions to the basal lamina. Hence, the transepithelial resistance can be described in terms of the net RTJ and RLIS as follows: transepithelial resistance ≈ paracellular resistance (RTE) = RTJ + RLIS. Recent studies validated that statement in vaginal-cervical epithelia (21, 22).

Determinations of RTE were carried out using cultures of CaSki cells attached to filters according to a method previously described (2). Before experiments, filters containing cells were washed three times and pre-incubated for 15 min at 37 C in a modified Ringer buffer composed of (in mM) NaCl (120), KCl (5), NaHCO3 (10, before saturating with 95% O2/5% CO2), CaCl2 (1.2), MgSO4 (1), glucose (5), HEPES (10) (pH 7.4), and 0.1% BSA in volumes of 4.7–5.2 ml in the luminal and subluminal compartments. Changes in paracellular permeability were determined in terms of changes in RTE across filters mounted vertically in a modified Ussing chamber, from successive measurements of the transepithelial potential difference (ΔPD, lumen negative) and the transepithelial electrical current (ΔI, obtained by measuring the current necessary to clamp the offset potential to zero, and normalized to the 0.6-cm2 surface area of the filter) as RTE = ΔPD/ΔI (15). The experimental design of the electrophysiological measurements, including calibrations and controls, the significance of the ΔPD and ΔI, and the conditions for optimal determinations of RTE across low-resistance epithelia, e.g. CaSki, were described and discussed (15).

Determinations of changes in RTJ

To assess more directly changes in RTJ, changes in the dilution potential (Vdil) and the epithelial ionic permeabilities of Cl− and Na+ were determined (15). Vdil was determined by measuring the effect of lowering NaCl in the luminal solution on changes in voltage generated across the epithelial culture. This was done by replacing the Ringer’s buffer in the luminal compartment (130 mM NaCl) with low (10 mM) NaCl solution. The latter buffer was similar to the Ringer’s solution except that it lacked the 120 mM NaCl and was supplemented with 240 mM sucrose to compensate for osmolarity. The methods of electrophysiological data evaluation were described (15, 20). Vdil was the measured potential difference (voltageSL – voltageL) after lowering NaCl in the luminal solution, corrected for the potential electrodes asymmetry, where the subscripts SL and L are the subluminal and luminal solutions. The Henderson diffusion equation for monocations and monoanions was used to interpret the transepithelial Vdil in terms of the ionic permeabilities of Cl− and Na+ as UCl/UNa. With the assumption that Na+ and Cl− are the major permeant ionic species, the relative mobilities of Na+ and Cl− in the intercellular space UCl and UNa can be determined as UCl/UNa = (K + |Vdil|)/(K − |Vdil|), where K ~ (R × T/F) × ln(NaSL/NaL) = 68.5 mV at the given [Na+SL] = 130 mM, and [Na+L] = 10 mM (21, 22).

RT-PCR

The method was described (23). Total RNA from cultured CaSki cells was isolated with the QIAGEN kit (QIAGEN Inc., Chatsworth, CA), using lysis buffer plus β-mercaptoethanol at 350 μl per 107 cells. The final total RNA pellets were resuspended in 50 μl diethylpyrocarbonate-water and quantitated by measuring OD260. The following PCR conditions were applied: for occludin, 25 cycles of 3 min denaturation at 94 C, 45 sec of annealing step at 60 C, and 75 sec of extension step at 72 C; for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), 30 cycles of 1 min at 93 C, 1 min at 60 C, and 1 min at 72 C. The following oligonucleotide primers were used: human occludin (GenBank accession number U49184), forward (sense) 5′-CGG GAT GTC ATC GAG GCC TTT TGA GAG TCC ACC T-3′ and reverse (antisense) 5′-GTC GAC CTA TGT TTT CTG TCT ATC ATA GTC TCC-3′; human GAPDH (24), forward (sense) 5′-TGA AGG TCG GAC TCA ACG GAT TTG GT-3′ and reverse (antisense) 5′-GTG GTG GAC CTC ATG GCC CAC ATG-3′. Assays yielded transcripts of 670 bp (occludin) and 932 bp (GAPDH).

Occludin antisense oligonucleotides assays

Occludin-specific antisense oligonucleotides (ASO) and random control oligonucleotides (CLO) were designed from the published sequence of human occludin (GenBank accession number U49184) by using HYB-simulator (Advanced Gene Computing Technologies, Irvine, CA) and choosing the melting temperature of the oligonucleotides as 34 C. Possible sequences that would have the given melting temperature were identified from the target mRNA, and the cross-hybridization against the whole sequence in the GenBank database of each oligonucleotide was calculated. A 19-mer ASO that would hybridize to the coding region of the occludin mRNA was selected as TTG ATC GTT ACA TAC TCT G. The control was a 19-mer CLO TAG AAC GTT ACT TAC ACT G in which the antisense sequence was randomly replaced with adenine and thymine residues so that the oligonucleotides had the same length (19-mer) and GC content (32%) as the antisense oligonucleotides. The CLO was designed such that no cross-hybridization against the occludin gene would occur. To assess the effects of the ASO and CLO on occludin mRNA expression, CaSki cells on filters were treated with or without ASO or CLO at concentrations of 10 μM. RT-PCR assays were carried out after 2 d, and protein and RTE determinations after 3–4 d.

Semiquantitative analysis of ASO and CLO effects on occludin was done in reference to effects on RNA levels of the housekeeping gene GAPDH (23). To ascertain that the RT-PCR technique is sensitive in measuring changes in the expression of occludin and GAPDH mRNA, experiments were done using different amounts of cDNA for the PCR amplification. Results (not shown) indicated that the quantity of the amplified products of occludin and GAPDH were dependent on the amount of cDNA used for the amplification. To ascertain that the RT-PCR technique can yield interpretable semiquantitative results, the effect of number of PCR cycles on the expression of occludin and GAPDH mRNA was determined. Results (not shown) indicated that the quantities of the amplified products of both occludin and GAPDH were dependent on the number of PCR cycles and that the conditions used provided amplification conditions for log-phase – synthesis.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting assays

After treatments, cells collected from 100-mm culture dishes were lysed at 4 C for 30 min in lysis buffer, composed of 1% Triton X-100, 0.2% SDS, proteinase inhibitors (Halt protease inhibitor cocktail kit; Pierce, Rockford, IL), 10 μM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 250 mM NaF, 200 mM β-glycerol phosphate, 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.3), and 25 mM EDTA. Samples were normalized by adjusting total protein level in each sample to 500 μg. The mixture was spun at 10,000 × g for 5 min; the supernatant was precleared with protein G agarose beads and incubated overnight at 4 C with rabbit antioccludin antibody. Protein-A agarose beads were added to pull down the immune complexes by incubating for 2 h at 4 C, and the beads were washed with PBS and eluted with 2× lysis buffer. The immunoprecipitated proteins were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to Immobilon membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA). The membranes were blocked with 1% BSA in PBS overnight at 4 C and incubated with mouse antioccludin antibody, or antiphosphothreonine, antiphosphoserine or antiphosphotyrosine antibodies for 2 h at room temperature. Secondary antibodies were peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse or antirabbit IgG (H+L). The reaction was visualized by ECL kit from Pierce (Rockford, IL).

Immunostaining

Cells cultured on filters were fixed with methanol, blocked with blocking buffer, and incubated with antioccludin antibody as described (11). Occludin immunostaining was visualized with donkey antirabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 488 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR).

Antibodies

Rabbit antioccludin antibody (catalog no. 71-1500) and mouse antioccludin antibody (catalog no. 33-1500) were from Zymed Laboratory Inc. (San Jose, CA). Both antibodies are directed against a stretch of 150 amino acids at the occludin C terminal, and were used for occludin immunoprecipitation and occludin Western blots, respectively. Antitubulin antibody was from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank at the University of Iowa (Iowa City, IA) and was diluted 1:500 for Western blots. Antiphosphothreonine, antiphosphotyrosine PY20 and P99, and antiphosphoserine antibodies were from Zymed. Mouse mono-clonal antirabbit GAPDH antibody was from HyTest (Turku, Finland). Donkey antirabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 488 was from Molecular Probes.

Densitometry

Densitometry was done using AGFA Arcus II scanner (AGFA, New York, NY) and version 5.1 of Un-Scan-It gel automated digital software (Silk Scientific, Orem, OR).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means (± SD), and significance of differences among means was estimated by Student’s t test. Trends were analyzed by ANOVA.

Chemicals and supplies

All chemicals, unless specified otherwise, were obtained from Sigma. The sn-1,2-dioctanoyl diglyceride (diC8) and N-acetyl-leucinyl-leucinyl-norleucinal (ALLN) were initially dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide and then in saline for a final 1000× stock.

Results

ATP effects on paracellular permeability

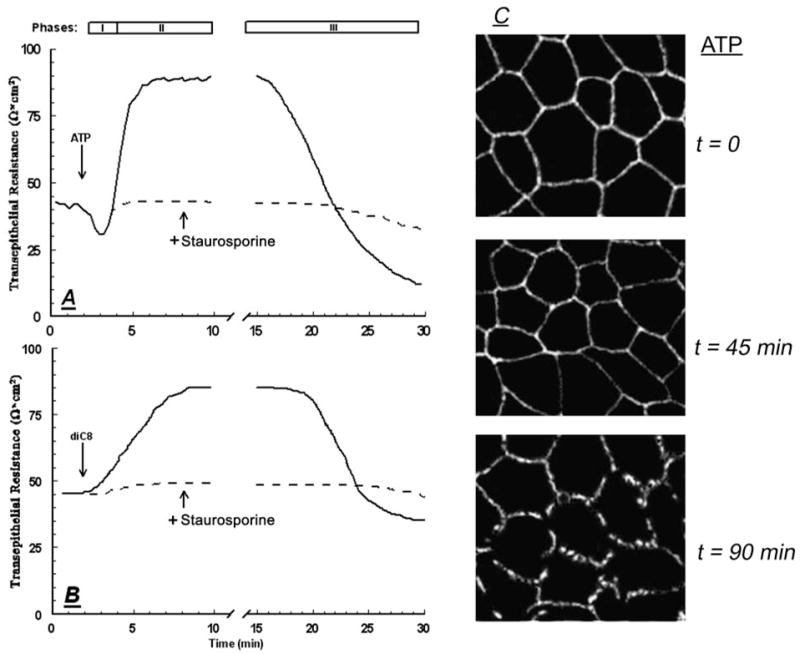

Treatment with 10 μM ATP induced a triphasic change in RTE: an immediate transient decrease in resistance, phase-I response (lasting about 2 min); followed by a longer transient increase in resistance, phase-II response (lasting 10–15 min); and a late decrease in RTE, phase-III response, that began about 15 min after adding the ATP and continued past the 30 min of the experiment (Fig. 1A). ATP phase-I and phase-II responses were previously described and characterized (25–27). However, until recently, less was known about the phase-III response, and one of our objectives was to better understand the mechanisms that mediate the ATP-induced late decrease in RTE.

FIG. 1.

CaSki cells on filters were treated with 10 μM ATP (A) or with 10 μM diC8 (B), added to both the luminal and subluminal solutions, in the absence (solid lines) or presence of 10 μM staurosporine (broken lines). Changes in transepithelial permeability were determined in terms of RTE. The effects of ATP include an immediate decrease in RTE (phase-I), followed by a transient increase in RTE (phase-II), and a late decrease in RTE (phase-III). Experiments were repeated four to seven times with similar trends, and data are summarized in Table 2. C, Effects of ATP on occludin expression. CaSki cells on filters were treated with 10 μM ATP for 45 min, and cells attached on filters were fixated and immunostained with rabbit antioccludin antibody (×20).

Similar to the reported phase-I and phase-II responses (25–27), the threshold of ATP for the phase-III response was 10 nM, and the effect reached saturation at 25 μM (not shown). The phase-I and phase-II effects were reversible, and removal of the ATP by replacing the bathing solutions with fresh medium restored RTE to baseline levels. In contrast, the phase-III effect was reversible only if ATP was removed within 30 min after treatment (not shown). Treatments with ATP for 45 min did not cause significant cell death (28), indicating that phase-I and phase-II responses, as well as early stages of the phase-III response, are not the result of toxic effect or cell death.

The phase-I response involves a decrease in RLIS, whereas the phase-II effect is the result of increased RTJ (25–27). To determine whether the phase-III response involves changes in RTJ, effects of ATP on the Vdil and the relative mobilities of Cl− and Na+ (UCl/UNa) in the intercellular space were determined (21, 22). As is shown in Table 1, UCl/UNa did not change during the phase-I response, but it decreased during the phase-II response, confirming that phase-II is the result of increased RTJ. UCl/UNa increased during phase-III (Table 1), indicating that the phase-III decrease in resistance is the result of decreased RTJ.

TABLE 1.

Modulation of transepithelial permeability by occludin antisense oligonucleotides

| Treatments | RTE (Omega;-cm2) | UCl/UNa |

|---|---|---|

| V | 39 ± 4 | 1.29 ± 0.02 |

| CLO | 42 ± 5 | 1.30 ± 0.01 |

| ASO | 24 ± 3a | 1.35 ± 0.01a |

Means (± SD) of three experiments in each point. Experiments are described in the text. Changes in transepithelial permeability were determined in terms of RTE, and changes in RTJ were determined in terms of UCl/UNa.

P < 0.02 (ANOVA).

Modulation of changes in RTJ by H7 and staurosporine

Pretreatment with 1-(5-isoquinolinylsulfonyl)-2-methyl piperazine (H7, 25 μM) or with staurosporine (10 nM) had no effect on baseline RTE or on ATP phase-I response (Table 1). In contrast, the drugs inhibited ATP phase-II and phase-III responses (Fig. 1A and Table 1). Treatment with 10 μM of the stable cell-permeable diacylglyceride diC8 mimicked phase-II (Fig. 1B) (15) and phase-III responses (Fig. 1B). The effects induced by diC8 were also blocked with H7 and staurosporine (Fig. 1B and Table 1). These data suggest that phase-II and phase-III responses are mediated by protein kinase C.

Effects of ATP and diC8 on the expression and cellular content of occludin

Immunostaining of CaSki cells with antioccludin antibody revealed immunoreaction localized to the plasma membrane (Fig. 1C). Treatment with ATP for less than 45 min had no significant effect on the occludin immunostaining (not shown). However, already 45 min after treatment with ATP the staining became granular, and 90 min after the treatment it became disrupted (Fig. 1C), suggesting disassembly of the tight junctions (Fig. 1C).

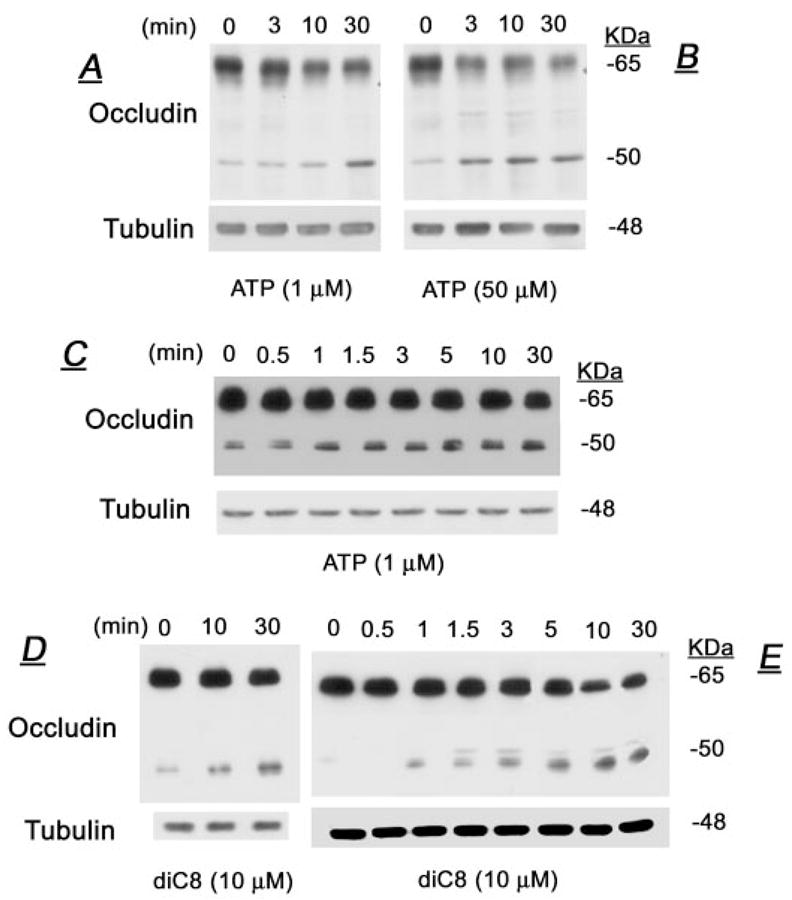

In lysates of CaSki cells, antioccludin antibodies immunoreacted with 65- and 50-kDa forms (e.g. Fig. 2A). The 65-kDa form is most likely the native functional occludin isoform (9, 10, 14). In contrast, until recently, less was known about the origin and function of the 50-kDa form, and the main objective of the present study was to understand those characteristics. In most experiments, the occludin 50-kDa form was detected as a single band (see, e.g. Figs. 2, 4, and 7) (11). In some experiments (see, e.g. Fig. 9A), a cluster of 48–50 kDa was detected. By using immunoprecipitation/immunoblotting with rabbit and mouse antioccludin antibodies, respectively, it was possible to better assess the relative densities of occludin 65- and 50-kDa forms. In cells treated with ATP (1 μM, Fig. 2A, or 50 μM, Fig. 2B), the density of the 65-kDa form decreased and the density of the 50-kDa form increased in a time-related manner (Fig. 2, A and B). In contrast, ATP had no effect on the expression of tubulin (Fig. 2, A–C). A more detailed analysis is shown in Fig. 2C and summarized in Fig. 3A. The figures show that significant decreases in the 65-kDa form and increases in the 50-kDa form began less than 10 min after treatment with ATP and tended to stabilize thereafter. Treatment with 10 μM diC8 induced similar effects on the densities of the 65- and 50-kDa forms (Figs. 2, D and E, and 3B), without affecting tubulin (Fig. 2, D and E).

FIG. 2.

Effects of ATP (A–C) and diC8 (D and E) on the cellular densities of occludin. At designated times after treatments, cells were lysed and total homogenates were immunoprecipitated and immunoblotted with antioccludin antibodies as described in the text. Shown are data of changes in occludin 65- and 50-kDa forms. Membranes were deprobed and immunoblotted with antitubulin antibody. Experiments were repeated two to four times with similar trends.

FIG. 4.

Effects of ATP (50 μM) (A and B) and diC8 (10 μM) (C and D) on the phosphorylation of occludin 65- and 50-kDa forms at threonine (PT) (A and C) and tyrosine (PY) (B and D) residues. At designated times after treatments, cells were lysed and total homogenates were immunoprecipitated with antioccludin antibody and immunoblotted with either antiphosphothreonine or antiphosphotyrosine antibodies. Experiments were repeated twice with similar trends.

FIG. 7.

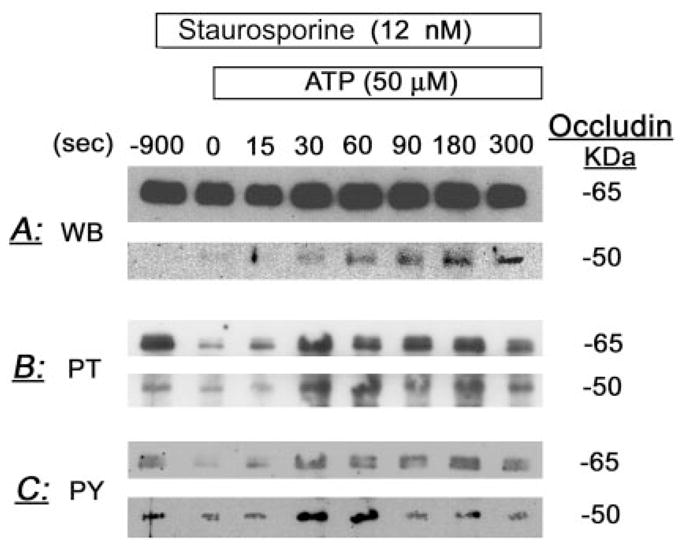

Staurosporine modulation of ATP changes in the densities and phosphorylation of occludin 65- and 50-kDa forms. Cells were pretreated for 15 min with 12 nM staurosporine, followed by 50 μM ATP. At times 0–5 min after treatments, cells were lysed and total homogenates were immunoprecipitated with antioccludin antibody. Immunoblots used either antioccludin antibody (WB, Western blots) (A), or antiphosphothreonine (PT) (B) or antiphosphotyrosine antibodies (PY) (C).

FIG. 9.

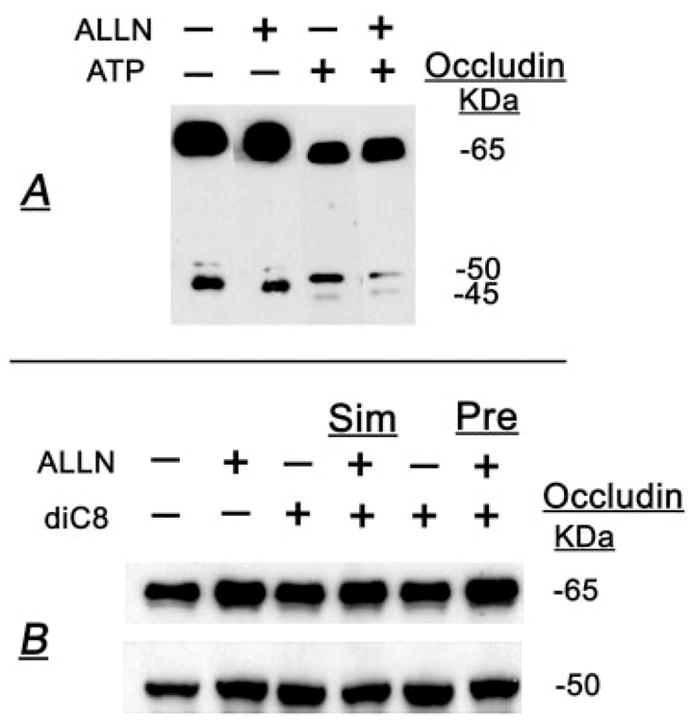

ALLN modulation of ATP (A) and diC8 (B) effects on the densities of occludin 65- and 50-kDa forms. A, Cells were treated for 30 min with 50 μM ALLN or the vehicle and then cotreated with 50 μM ATP (or the vehicle) for an additional 30 min. B, Treatments were as follows: vehicles (lane 1), 50 μM ALLN (lane 2), and 10 μM diC8 for 30 min (lanes 3 and 5); 50 μM ALLN plus 10 μM diC8 for 30 min (lane 4) (Sim, simultaneous); and 50 μM ALLN for 30 min followed by 10 μM diC8 for an additional 30 min (lane 6). At the completion of treatments, cells were lysed, and total homogenates were immunoprecipitated and immunoblotted with antioccludin antibody.

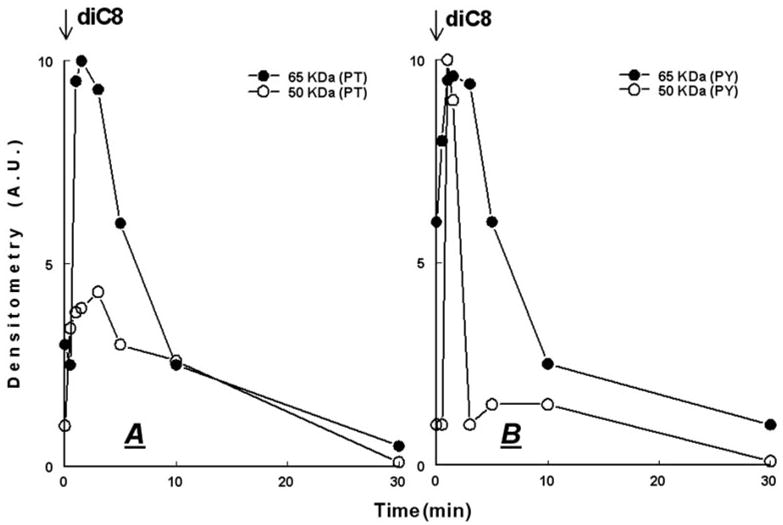

FIG. 3.

Effects of ATP (A) and diC8 (B) on the cellular densities of occludin 65- and 50-kDa forms: densitometry analysis of the data shown in Fig. 2, C and E. A.U., Arbitrary units.

Effects of ATP and diC8 on occludin phosphorylation

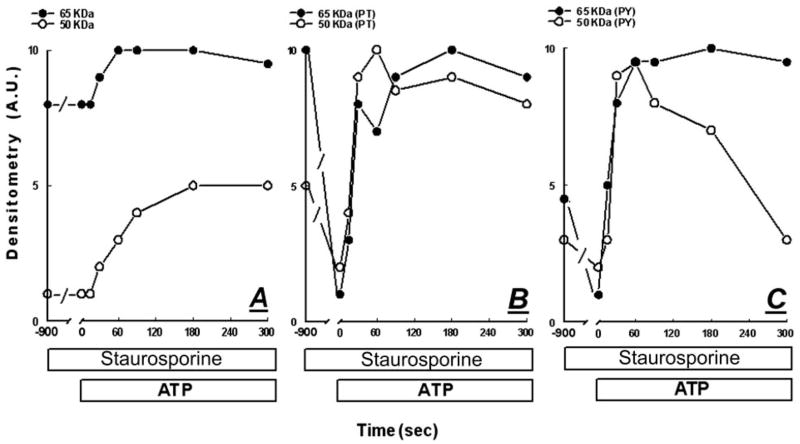

To determine the effects of ATP and diC8 on occludin phosphorylation, CaSki cells were treated with 50 μM ATP (Fig. 4, A and B) or with 10 μM diC8 (Fig. 4, C and D). At 0–30 min after treatments, cells were homogenized and lysates were immunoprecipitated with rabbit antioccludin antibody and immunoblotted with antiphosphothreonine, antiphosphotyrosine PY20 and P99, or antiphosphoserine antibodies. At baseline, both the 65-kDa form (Figs. 4, A and C, and 7B) and the 50-kDa form (Figs. 4, B and D, and 7B) were phosphorylated on threonine residues. Treatment with ATP decreased acutely and transiently threonine phosphorylation of the 65-kDa form and induced a parallel reciprocal transient increase in threonine phosphorylation of the 50-kDa form (Fig. 4A). Densitometry analysis of the data showed that the decrease in threonine phosphorylation of the 65-kDa form began within 1 min of treatment, followed by gradual recovery after 10 min. However, threonine phosphorylation failed to reach baseline levels even after 30 min of treatment (Figs. 4A and 5A). The increases in threonine phosphorylation of the 50-kDa form paralleled reciprocally the decreases in threonine phosphorylation of the 65-kDa form (Figs. 4A and 5A).

FIG. 5.

Densitometry analysis of the effects of ATP on the phosphorylation of occludin 65- and 50-kDa forms at threonine (PT, B) and tyrosine (PY, C) residues. Data are from Fig. 4, and results are normalized to the densities of total occludin 65- and 50-kDa isoforms (A).

At baseline, the 65- and 50-kDa forms were phosphorylated also on tyrosine residues (Figs. 4, B and D, and 7C). Treatment with ATP increased acutely and transiently tyrosine phosphorylation of both the 65- and 50-kDa forms (Figs. 4B and 5B). Tyrosine phosphorylation of the 65-kDa form remained above baseline even 30 min after adding the ATP, whereas that of the 50-kDa form decreased at 30 min to sub-baseline levels (Figs. 4B and 5B).

Treatment with diC8 increased threonine (Figs. 4C and 6A) and tyrosine phosphorylation (Figs. 4D and 6B) of both the 65- and 50-kDa forms. Increases in phosphorylation began within 1 min of treatment, were transient, and returned to baseline levels of phosphorylation 10–30 min after treatment.

FIG. 6.

Densitometry analysis of the effects of diC8 on the phosphorylation of occludin 65- and 50-kDa forms at threonine (PT) (A) and tyrosine (PY) (B) residues. Data are from Fig. 4, and results are normalized to the densities of total occludin 65- and 50-kDa isoforms.

At baseline, the 65- and 50-kDa forms were phosphorylated also on serine residues, but neither ATP nor diC8 had any appreciable effect on the serine phosphorylation (not shown).

Controls for the occludin phosphorylation experiments included coincubations with phosphothreonine, phosphoserine, or phosphotyrosine. In all cases, the immunoreactivities detected with the antiphosphothreonine, antiphosphoserine, or antiphosphotyrosine antibodies were blocked by coincubations with the respective phosphoproteins (not shown).

Collectively, the results in Figs. 4–6 indicate that ATP and diC8 modulate threonine and tyrosine phosphorylation of occludin 65- and 50-kDa forms within seconds or minutes. The effect of ATP differed from that of diC8 because ATP decreased transiently threonine phosphorylation of the 65-kDa form, whereas diC8 increased transiently the threonine phosphorylation. However, in both cases, the acute increases in RTJ correlated in time with the acute decreases in threonine phosphorylation (Fig. 1, A and B, vs. Figs. 5A and 6A).

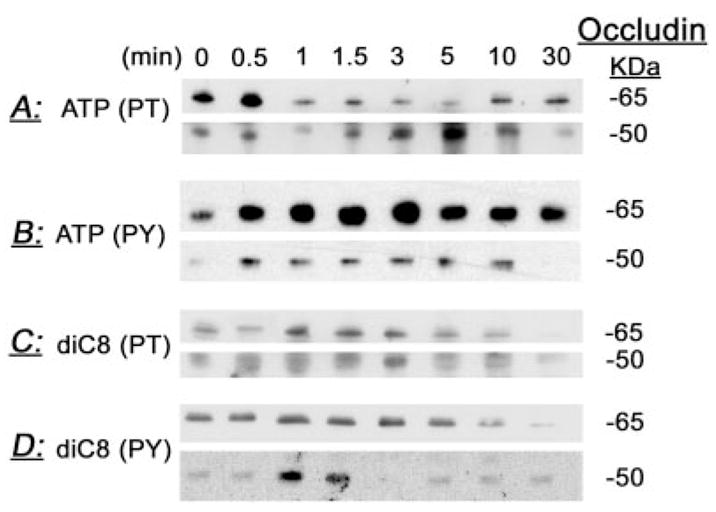

Effects of staurosporine on occludin content and phosphorylation

To determine the degree to which staurosporine modulates ATP changes in occludin content and phosphorylation status, cells were treated with 12 nM staurosporine 15 min before treatments. The experiments focused on changes of occludin within the first 5 min of ATP treatment because the major changes in occludin phosphorylation occurred during this period of time (Figs. 4, A and B, and 5, A and B).

Treatment with staurosporine had little effect on baseline content of occludin 65- and 50-kDa forms (Figs. 7A and 8A). However, in cells pretreated with staurosporine, ATP increased acutely the 65-kDa form (Figs. 7A and 8A), in contrast to a mild decrease in cells treated with ATP alone (Figs. 2, A–C, and 3A). Staurosporine did not affect the ATP increase of the 50-kDa form (Figs. 7A and 8A; compare with Figs. 2, A–C, and 3A).

FIG. 8.

Densitometry analysis of staurosporine modulation of ATP changes in the densities of occludin 65- and 50-kDa forms (A) and occludin phosphorylation at threonine ((PT) (B) and tyrosine (PY) (C) residues. Data are from Fig. 7, and results are normalized to the densities of total occludin 65- and 50-kDa isoforms.

Treatment with staurosporine decreased baseline threonine and tyrosine phosphorylation of both the 65- and 50-kDa occludin forms (Figs. 7B and 8B). Pretreatment with staurosporine did not affect significantly ATP modulation of threonine phosphorylation of the 50-kDa form or tyrosine phosphorylation of the 65- and 50-kDa forms (Figs. 7, B and C, and 8, B and C, vs. Figs. 4, A and B, and 5, A and B). However, pretreatment with staurosporine reversed the ATP effect on threonine phosphorylation of the 65-kDa form; in cells pretreated with staurosporine, ATP induced an acute increase in the phosphorylation of the 65-kDa form (Figs. 7B and 8B vs. Figs. 4A and 5A).

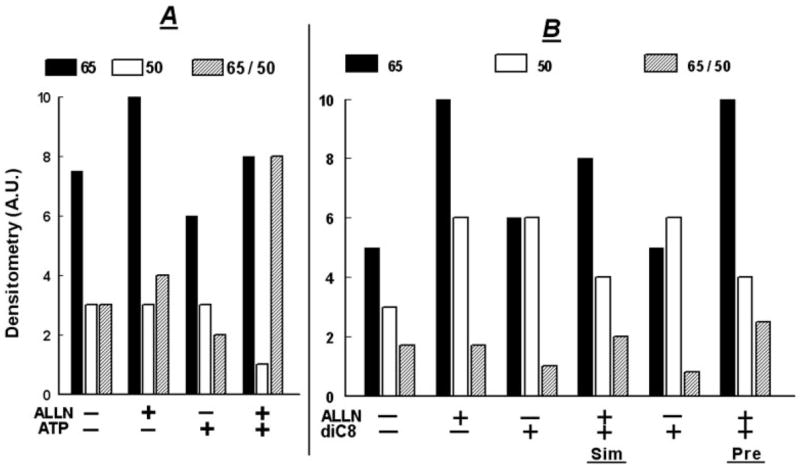

ALLN modulation of RTJ and occludin content

ATP phase-III response (Fig. 1A) correlated in time with decreases in the 65-kDa form and with increases in the 50-kDa form (Figs. 2, A–C, and 3A). To test the degree to which the ATP-induced changes in occludin are protease dependent, cells were treated for 30 min with 50 μM ALLN, inhibitor of calpains, a family of Ca2+ -activated neutral cysteine proteases. Endpoints were changes in RTE and the ratio UCl/UNa and cellular content of occludin 65- and 50-kDa forms.

Treatment with ALLN had no significant effect on baseline RTE and on the ratio UCl/UNa or on ATP-induced changes in RTE and UCl/UNa during phase-II response (Table 1). In contrast, pretreatment with ALLN attenuated the decreases in RTE and the increases in UCl/UNa induced by ATP at the phase-III response and the decreases in RTE and increases in UCl/UNa induced by diC8 (Table 1).

Treatment with ALLN increased the density of the 65-kDa form (Figs. 9, A and B, and 10, A and B), and either it had no effect (Fig. 9A) or it also increased the density of the 50-kDa form (Fig. 9B). Pretreatment with ALLN attenuated the ATP-induced decrease in the 65-kDa form, and the ATP-induced increase in the 50-kDa form (Figs. 9A and 10A). To better assess the changes, the correlation analysis used the ratio of 65-kDa/50-kDa as an added parameter of occludin modulation, because the 65- and 50-kDa forms are the major iso-forms of occludin in CaSki cells (11). When expressed in terms of the ratio of densities of the 65-kDa/50-kDa forms, ATP alone decreased the ratio to about 1:3, but in cells pre-treated with ALLN, ATP more than doubled the ratio (Figs. 9A and 10A). ALLN produced similar effects in cells treated with diC8, regardless of whether ALLN was added together with the diC8 or 30 min before diC8 (Figs. 9B and 10B).

FIG. 10.

ALLN modulation of ATP (A) and diC8 (B) effects on the densities of occludin 65- and 50-kDa forms: densitometry analysis of the data shown in Fig. 9. In A, lanes 1 and 2, densitometry assessed the 48-kDa forms and in lanes 3 and 4 the 50-kDa forms.

These results suggest that the ATP- and diC8-induced decreases in the density of the 65-kDa form and the increases in the density of the 50-kDa form are mediated by calpain-dependent proteolysis of the 65-kDa form to a smaller byproduct of 50 kDa.

Down-regulation of occludin

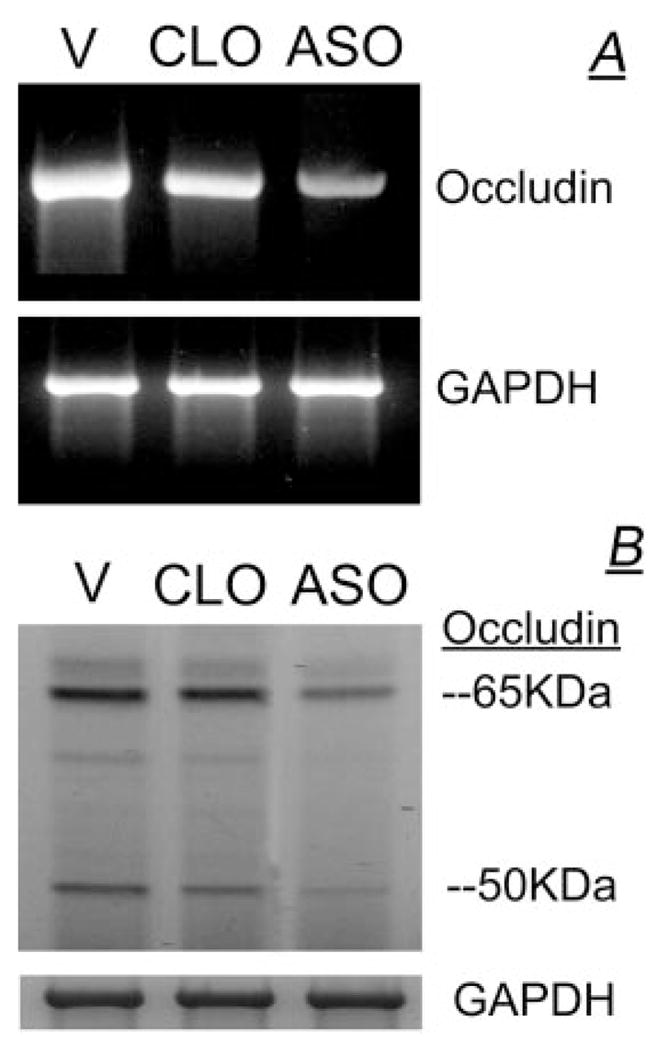

To determine to what degree down-regulation of occludin RNA could modulate expression of occludin 65- and 50-kDa isoforms, CaSki cells were treated with ASO, and effects on steady-state occludin mRNA and on occludin 65- and 50-kDa isoforms were determined relative to effects in cells treated with the empty vector (V) or cells treated with CLO.

Compared with cells that were transfected with V, a significant reduction in occludin mRNA was observed after ASO treatment, whereas no inhibitory effect on mRNA expression was detected after CLO treatment (Fig. 11A). In parallel experiments, treatments with the ASO or CLO had no effect on GAPDH mRNA (Fig. 11A). Densitometry revealed a reduction by 70% of the ratio of occludin RNA/GAPDH RNA in ASO-treated cells vs. V- or CLO-treated cells.

FIG. 11.

CaSki cells were treated with the V, with CLO, or with ASO. A, RNA data; B, cell lysates were immunoblotted with the antihuman occludin antibody, and membranes were reprobed with anti-GAPDH antibody.

To understand the effect of the ASO on occludin protein expression, lysates of cells treated with V or of cells treated with the ASO or CLO were immunoblotted with the anti-human occludin antibody. As is shown in Fig. 11B, a significant reduction in occludin 65- and 50-kDa isoforms was observed after ASO treatment compared with V- or CLO-treated cells. Treatments with ASO or CLO had no significant effect on GAPDH (Fig. 11B). Densitometry revealed decreases of 60 and 70% in ASO-treated cells compared with V-or CLO-treated cells in the ratios of occludin 65-kDa/GAPDH and occludin 50-kDa/GAPDH, respectively. Collectively, these results indicate that treatment with ASO down-regulated occludin mRNA and decreased expression of both occludin 65- and 50-kDa isoforms.

In parallel experiments, effects of treatments with ASO and CLO on RTE were also determined. As is shown in Table 1, treatment with ASO resulted in a significant decrease in RTE and an increase in the ratio of UCl/UNa, indicating a decrease in RTJ.

Correlation between changes in RTJ and occludin content

Figure 12 shows correlation analyses of changes in RTE and cellular densities of occludin 65- and 50-kDa forms. Included in the analysis were resistance levels determined during phase-II and phase-III responses, and the correlation analysis therefore pertains to changes in RTJ. At low levels of resistance of 10–50 Ω-cm2, RTE correlated positively with the 65-kDa form and with the ratio 65-kDa/50-kDa (Fig. 12, A and C) and negatively with the 50-kDa form (Fig. 12B). At high levels of resistance, 70–90 Ω-cm2 (determined during ATP phase-II or 5–15 min after adding diC8), the densities of the 65- and 50-kDa forms were high, and no correlation with RTE was found (Fig. 12, A and B); however, at high levels of resistance, the ratio 65-kDa/50-kDa correlated negatively with RTE (Fig. 12C). The most likely explanation for the latter result is that the densities of the 50-kDa form were relatively higher than the corresponding densities of the 65-kDa (Fig. 12, B vs. A). Collectively, the results in Fig. 12 indicate that high RTJ levels correlate predominantly with the 65-kDa form and are not influenced significantly by the 50-kDa form. In contrast, low levels of RTJ correlate negatively with the 65- kDa form and positively with the 50-kDa form.

FIG. 12.

Correlation between RTE and the densities of occludin 65-kDa form (A), occludin 50-kDa form (B), and the ratio of 65-kDa/50-kDa (C). Densitometry data of occludin were obtained from the experiments described in Figs. 2 and 9 and was correlated with data of RTE obtained in Fig. 1 and Table 2. In A–C, correlations for RTE levels of 10–50 Ω-cm2 were significant (P < 0.05–0.03). In C, the correlation for RTE levels of 70–90 Ω-cm2 was significant (P < 0.02).

Discussion

Treatment of CaSki cells with ATP induced an acute and transient increase in RTJ that could be reversed by removing the ATP and is possibly the result of modulation of assembled tight junctions. Treatment with ATP also induced a slower decrease in resistance (phase-III response) that could be reversed only if the drug was removed within 30 min of treatment. Treatment for longer periods of time caused an irreversible decrease in RTJ and morphological evidence of tight junction breakdown, suggesting that the phase-III decrease in RTJ is the early stage of tight junctions disassembly.

The RTJ effects of ATP were associated with changes in the expression and phosphorylation of occludin, but not claudin-4, suggesting that in human cervical epithelia, occludin plays a role in the ATP regulation of resistance. Occludin is a phosphoprotein, and studies in other types of cells have shown that phosphorylation of occludin (14) by protein kinase C (14, 29–31), RhoA-p160ROCK (32), or the ERK1/2 (33) can modulate the RTJ. In CaSki cells under steady-state conditions, the occludin 65-kDa form was phosphorylated on threonine, tyrosine, and serine residues. Treatment with staurosporine decreased threonine and tyrosine phosphorylation of occludin 65-kDa form, suggesting that occludin is being constitutively phosphorylated at threonine and tyrosine residues by a staurosporine-sensitive mechanism. One possible explanation is that protein kinase C stimulates phosphorylation of occludin constitutively, and treatment with ATP modulates the effect by increasing tyrosine phosphorylation and by stimulating threonine dephosphorylation (present results). An alternative explanation is the involvement of other pathways, because indolocarbazole compounds such as H7 and staurosporine can also inhibit cyclin-dependent kinases and topoisomerase-I (34, 35). The possibility that a cyclin-dependent kinase constitutively phosphorylates occludin is intriguing because increased phosphorylation of occludin at threonine residues predicts decreased gating of assembled tight junctions (see below). In addition, increased phosphorylation of occludin at tyrosine residues was associated with disassembly of tight junctions (present results). Thus, it is possible that decreased gating of assembled tight junctions and disassembly of tight junctions are required for cell cycle progression.

Neither ATP nor diC8 had an appreciable effect on serine phosphorylation (not shown), which is in contrast to MDCK cells where occludin Ser338 is a phosphorylation site of protein kinase C (19).

One of the objectives of the present study was to better understand the signaling and mechanism of ATP phase-II increase in RTJ. The proximal steps of the phase-II signaling cascade were previously studied; the results suggest involvement of activation of pertussis toxin-sensitive, G protein-coupled, dihydropyridine-sensitive voltage-dependent P2X4 receptor-operated calcium channels (25–27). Enhanced calcium influx stimulates activation of phospholipase-D and the release of diacylglycerol (25). Based on the present diC8 results, possible downstream signaling cascades could be chimaerins, RasGRPs, MUNC13s, protein kinase-D, and diacylglycerol kinases β and γ (36). A more likely target of the diacylglycerol could be protein kinase C, because the phase-II increase in RTJ was mimicked by treatment with the diacylglyceride diC8 and blocked with the protein kinase C inhibitors H7 and staurosporine (present results). Moreover, in other types of cells, prolonged activation of protein kinase C leads to disassembly of tight junctions (14). Pretreatment with staurosporine also blocked the diC8-induced increase in RTJ, suggesting that the ATP phase-II and the diC8-induced acute increases in RTJ are mediated by protein kinase C.

Treatment with ATP also induced an acute and transient decrease in threonine phosphorylation of the occludin 65-kDa form. Pretreatment with staurosporine reversed the effect, so that in staurosporine-treated cells, ATP induced an acute and transient increase in threonine phosphorylation. These findings suggest that the phase-II acute increase in RTJ is mediated by staurosporine-sensitive threonine dephosphorylation of the 65-kDa form. The effect is possibly mediated by protein kinase C because diC8 also induced a transient increase in RTJ, and the diC8-associated decrease in threonine phosphorylation of occludin preceded and correlated in time with the increase in resistance. However, it is also possible that the effect requires tyrosine phosphorylation of occludin, because staurosporine alone had no effect on RTJ. Staurosporine alone decreased threonine phosphorylation of the 65-kDa form, but in addition, it also decreased tyrosine phosphorylation. Treatment with ATP, on the other hand, decreased threonine phosphorylation and increased tyrosine phosphorylation of occludin.

The molecular mechanism by which threonine dephosphorylation of occludin increases gating of the tight junctions is at present unknown, and it could be associated with conformational changes of occludin that increase gating of the intercellular space.

Another objective of the study was to understand the events that lead to disassembly of the tight junctions. Studies in other types of cells suggested that protein kinase C (14) as well as tyrosine phosphorylation of occludin mediate the effect. An example of the latter is the bovine aortic endothelium, where shear-stress-induced phosphorylation of occludin as well as the disassembly of tight junctions are mediated by tyrosine kinase (37). In addition, in Caco-2 cells, acetaldehyde-induced disruption of epithelial tight junctions involves tyrosine phosphorylation of junctional proteins by inhibition of tyrosine phosphatase (38). In vitro, tyrosine phosphorylation of occludin decreases occludin interaction with zonula occludens (ZO) proteins (39). In CaSki cells, treatments with ATP and diC8 increased acutely and transiently tyrosine phosphorylation of the occludin 65-kDa form, suggesting involvement of protein kinase C in the tyrosine phosphorylation of occludin. However, pretreatment with H7 or with staurosporine inhibited only in part the phase-III and diC8 decreases in RTJ, and pretreatment with staurosporine did not affect tyrosine phosphorylation of occludin. Therefore, protein kinase C is probably not the main effector of tyrosine phosphorylation of occludin, and the phase-III response is possibly mediated by signaling cascades other than tyrosine phosphorylation of occludin.

The present results suggest a novel cellular mechanism for the early stage of tight junction disassembly, namely the breakdown of the occludin 65-kDa form to the lesser functional 50-kDa form. The relevant experimental data can be summarized as follows: 1) the 50-kDa form is not the result of genomic mutation of occludin, and it is not a translational product of occludin splice variant (Gorodeski, G. I., unpublished results); 2) treatment with antisense oligonucleotides decreased occludin baseline mRNA and expression of both occludin 65- and 50-kDa isoforms and abrogated the RTJ; 3) treatments with estrogen (11) or with ATP and diC8 (present results) decreased the density of the 65-kDa form and increased the density of the 50-kDa form; 4) the decreases in the 65-kDa form correlated inversely with the increases in the 50-kDa form, and both effects correlated in time with decreases in RTJ (Ref. 11 and present results); 5) cotreatment with tamoxifen (estrogen antagonist in cervical cells) (40) blocked the estrogen-induced increase in the 50-kDa form and the decrease in RTJ (11); 6) [35S]methionine-labeling pulse-chase assays showed that treatment with estrogen up-regulates occludin 65-kDa synthesis and modulation of occludin into a 50-kDa form (11); and 7) pretreatment with the calpain inhibitor ALLN attenuated the ATP- and diC8-induced increases in the cellular density of the 50-kDa form relative to the 65-kDa form (present results). Collectively, these findings suggest that the 50-kDa isoform is regulated posttranslationally and that the ATP phase-III and diC8-induced decreases in RTJ involve calpain-dependent proteolysis of occludin 65-kDa to a 50-kDa form.

The third objective of the study was to better understand the biological role of the 50-kDa form. We found that treatments with ATP and diC8 modulated levels of threonine and tyrosine phosphorylation of the 50-kDa form. The 50-kDa form is possibly a fragment cleaved at the second extracellular loop of occludin (41–43), thereby containing the C terminus, fourth transmembrane stretch, and part of the second extracellular loop of occludin (11). The ability of the 50-kDa form to undergo tyrosine and threonine phosphorylation is explained by the fact that most of the tyrosine and threonine residues are in the C terminus of the molecule. The C terminus, which possibly remains intact in the 50-kDa form (11), contains 11 of the 14 potential tyrosine phosphorylation sites and all four potential threonine phosphorylation sites of the occludin molecule (9). Because the antioccludin antibodies used in the present study recognize the occludin C terminus, it was possible to detect the changes in the tyrosine and threonine phosphorylation.

Treatments with ATP and diC8 increased levels of tyrosine phosphorylation of the 50-kDa form, similar to the effect of the 65-kDa form. However, the pattern of threonine phosphorylation was different; ATP increased levels of threonine phosphorylation of the 50-kDa form but induced a decrease in threonine phosphorylation of the 65-kDa form. These findings suggest that modulation of phosphorylation of the 50-kDa form had occurred either during or after the 65- to 50-kDa conversion.

The findings suggesting that the 50-kDa form can undergo tyrosine and threonine phosphorylation raise the possibility that it remains a responsive isoform at the tight junctional complex. However, the finding that levels of threonine phosphorylation of the 50-kDa form did not decrease suggests that it cannot participate effectively in gating of the tight junctions. By comparing changes in the RTJ with changes in the densities of the 65- and 50-kDa forms it was found that RTJ correlated predominantly with the 65-kDa form; high levels of RTJ were associated with high cellular densities of the 65-kDa form and were unrelated to the density of the 50-kDa form. In contrast, low levels of resistance correlated with the 65-kDa form and inversely with the 50-kDa form (Fig. 12). Therefore, it is suggested that the 50-kDa form plays a secondary role in the modulation of RTJ by competing with the functional occludin 65-kDa form in the tight junctional complex.

In summary, the present novel data suggest that in cervical cells occludin determines gating of the tight junctions and that changes in occludin phosphorylation status and composition regulate the RTJ. The functional occludin 65-kDa form is constitutively phosphorylated on threonine and tyrosine residues and constitutively undergoes calpain-mediated transformation to a nonfunctional 50-kDa form. Because both processes predict occludin breakdown and abrogation of the RTJ, occludin must be continuously produced and transported to the tight junctional complex to maintain a steady-state level of junctional occlusion. The resistance of the assembled tight junctional complex can be increased acutely by protein kinase C-mediated threonine dephosphorylation of the 65-kDa form, whereas early stages of tight junction disassembly involve calpain-mediated breakdown of occludin 65-kDa form to the 50-kDa form. Moreover, increased levels of the 50-kDa form interfere with the occludin 65-kDa form gating of the tight junctions.

The present results could be relevant to our understanding of RTJ regulation in vivo, because the experimental conditions employed in the present study are similar to those that prevail in the cervix and vagina in vivo, where cervical-vaginal cells are exposed to varying levels of extracellular ATP at concentrations that suffice to activate the P2X4 receptor (28).

Supplementary Material

TABLE 2.

Modulation of transepithelial permeability by ATP and diC8

| Condition | RTE (Ω-cm2) | UCl/UNa |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 41 ± 3 | 1.29 ± 0.02 |

| ATP 1 min (phase-I) | 28 ± 4a | 1.30 ± 0.01 |

| ATP 6 min (phase-II) | 79 ± 5a | 1.23 ± 0.02a |

| ATP 30 min (phase-III) | 15 ± 3a | 1.37 ± 0.02a |

| diC8 10 min | 83 ± 7a | 1.23 ± 0.02a |

| diC8 30 min | 14 ± 4a | 1.37 ± 0.02a |

| Staurosporine 30 min | 38 ± 8 | 1.31 ± 0.02 |

| Staurosporine 30 min/ATP 6 min | 39 ± 5 | 1.29 ± 0.02 |

| Staurosporine 30 min/ATP 30 min | 28 ± 6a | 1.31 ± 0.02 |

| Staurosporine 30 min/diC8 30 min | 23 ± 2a | 1.31 ± 0.02 |

| H7 30 min | 44 ± 7 | 1.28 ± 0.03 |

| H7 30 min/ATP 6 min | 39 ± 8 | 1.31 ± 0.03 |

| H7 30 min/ATP 30 min | 27 ± 8a | 1.30 ± 0.03 |

| H7 30 min/diC8 30 min | 27 ± 5a | 1.33 ± 0.03a |

| ALLN 60 min | 45 ± 5 | 1.29 ± 0.02 |

| ALLN 60 min/ATP 6 min | 82 ± 2a,b | 1.23 ± 0.02b |

| ALLN 60 min/ATP 30 min | 25 ± 2a,b | 1.33 ± 0.02b |

| ALLN 60 min/diC8 30 min | 34 ± 4a,c | 1.31 ± 0.02b |

Means (± SD) of three to nine experiments in each point. Experiments are described in the text. CaSki cells were cultured on filters, and agents were added to both the luminal and subluminal solutions as follows: staurosporine, 10 nM; H7, 25 μM; ALLN, 50 μM; ATP, 1–50 μM; and diC8, 10 μM. For combined treatments, ATP or diC8 were added together with staurosporine or 30 min after pretreatment with ALLN. Changes in transepithelial permeability were determined in terms of RTE, and changes in RTJ were determined in terms of UCl/UNa.

P < 0.03–0.01 compared with baseline (paired t test).

P < 0.04 compared with ATP 30 min (ANOVA).

P < 0.01 compared with diC8 30 min (ANOVA).

Acknowledgments

The technical support of Kimberley Frieden, Brian De-Santis, and Dipika Pal is acknowledged.

The study was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants HD29924 and AG15955 (to G.I.G.).

Abbreviations

- ALLN

N-Acetyl-leucinyl-leucinyl-norleucinal

- ASO

occludin-specific antisense oligonucleotides

- CLO

random control oligonucleotides

- diC8

sn-1,2-dioctanoyl diglyceride

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- I

transepithelial electrical current

- PD

transepithelial potential difference

- RLIS

resistance of the lateral intercellular space

- RTE

transepithelial electrical resistance

- RTJ

resistance of the intercellular tight junctions

- UCl

ionic permeability of Cl−

- UNa

ionic permeability of Na+

- V

empty vector

- Vdil

dilution potential

- ZO

zonula occludens

References

- 1.Gorodeski GI. The cervical cycle. In: Adashi EY, Rock JA, Rosenwaks Z, editors. Reproductive endocrinology, surgery, and technology. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 301–324. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorodeski GI. The cultured human cervical epithelium: a new model for studying transepithelial paracellular transport. J Soc Gynecol Invest. 1996;3:267–280. doi: 10.1016/s1071-5576(96)00028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gorodeski GI, Merlin D, De Santis BJ, Frieden KA, Hopfer U, Eckert RL, Romero MF. Characterization of paracellular permeability in cultured human cervical epithelium: regulation by extracellular ATP. J Soc Gynecol Invest. 1994;1:225–233. doi: 10.1177/107155769400100309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin-Padura I, Lostaglio S, Schneemann M, Williams L, Romano M, Fruscella P, Panzeri C, Stoppacciaro A, Ruco L, Villa A, Simmons D, Dejana E. Junctional adhesion molecule, a novel member of the immunoglobulin superfamily that distributes at intercellular junctions and modulates monocyte transmigration. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:117–127. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.1.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furuse M, Sasaki H, Fujimoto K, Tsukita S. A single gene product, claudin-1 or -2, reconstitutes tight junction strands and recruits occludin in fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:391–401. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.2.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heiskal M, Peterson PA, Yang Y. The roles of claudin superfamily proteins in paracellular transport. Traffic. 2000;2:92–98. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2001.020203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morita K, Furuse M, Fujimoto K, Tsukita S. Claudin multigene family encoding four-transmembrane domain protein components of tight junction strands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:511–516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsukita S, Furuse M. Pores in the wall: claudins constitute tight junction strands containing aqueous pores. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:13–16. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ando-Akatsuka Y, Saitou M, Hirase T, Kishi M, Sakakibara A, Itoh M, Yonemura S, Furuse M, Tsukita S. Interspecies diversity of the occludin sequence: cDNA cloning of human, mouse, dog and rat kangaroo homologues. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:43–47. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Furuse M, Hirase T, Itoh M, Nagafuchi A, Yonemura S, Tsukita S, Tsukita S. Occludin: a novel integral membrane protein localizing at tight junctions. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:1777–1788. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.6.1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeng R, Li X, Gorodeski GI. Estrogen abrogates transcervical tight junctional resistance by acceleration of occludin modulation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:5145–5155. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorodeski GI. Estrogen biphasic regulation of paracellular permeability of cultured human vaginal-cervical epithelia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:4233–4243. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.9.7817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gorodeski GI. Aging and estrogen effects on transcervical-transvaginal epithelial permeability. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:345–351. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clarke H, Marano CW, Soler AP, Mullin JM. Modification of tight junction function by protein kinase-C isoforms. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2000;41:283–301. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gorodeski GI, Peterson D, De Santis BJ, Hopfer U. Nucleotide-receptor mediated decrease of tight-junctional permeability in cultured human cervical epithelium. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:C1715–C1725. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.270.6.C1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong V. Phosphorylation of occludin correlates with occludin localization and function at the tight junction. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:C1859–C1867. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.6.C1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muresan Z, Paul DL, Goodenough DA. Occludin 1B, a variant of the tight junction protein occludin. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:627–634. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.2.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghassemifar MR, Sheth B, Papenbrock T, Leese HJ, Houghton FD, Fleming TP. Occludin TM4−: an isoform of the tight junction protein present in primates lacking the fourth transmembrane domain. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:3171–3180. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.15.3171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andreeva AY, Krause E, Muller EC, Blasig IE, Utepbergenov DI. Protein kinase-C regulates the phosphorylation and cellular localization of occludin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38480–38486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104923200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gorodeski GI, Romero MF, Hopfer U, Rorke E, Utian WH, Eckert RL. Human uterine cervical epithelial cells grown on permeable support: a new model for the study of differentiation and transepithelial transport. Differentiation. 1994;56:107–118. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.1994.56120107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schultz SG. Diffusion potentials. In: Schultz SG, editor. Basic principles of membrane transport. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1980. pp. 42–56. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reuss L. Tight junction permeability to ions and water. In: Cereijido M, editor. Tight-junctions. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1991. pp. 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gorodeski GI. Role of nitric oxide and cGMP in the estrogen regulation of cervical epithelial permeability. Endocrinology. 2000;141:1658–1666. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.5.7473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gorodeski GI, Burfeind F, Uin GS, Pal D, Abdul-Karim F. Regulation by retinoids of P2Y2 nucleotide receptor mRNA in human uterine cervical cells. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:C758–C765. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.3.C758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gorodeski GI, Hopfer U, Wenwu J. Purinergic receptor induced changes in paracellular resistance across cultures of human cervical cells are mediated by two distinct cytosolic calcium related mechanisms. Cell Biochem Biophys. 1998;29:281–306. doi: 10.1007/BF02737899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gorodeski GI. Regulation of transcervical permeability by two distinct P2-purinergic receptor mechanisms. Am J Physiol. 2002;282:C75–C83. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2002.282.1.C75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gorodeski GI. Expression regulation and function of P2X4 receptor in human cervical epithelial cells. Am J Physiol. 2002;282:C84–C93. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2002.282.1.C84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Q, Wang L, Feng YH, Li X, Zeng R, Gorodeski GI. P2X7-receptor mediated apoptosis of human cervical epithelial cells. Am J Physiol. 2004;287:C1349–C1358. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00256.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Banan A, Zhang LJ, Shaikh M, Fields JZ, Farhadi A, Keshavarzian A. θ-Isoform of PKC is required for alterations in cytoskeletal dynamics and barrier permeability in intestinal epithelium: a novel function for PKC-θ. Am J Physiol. 2004;287:C218–C234. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00575.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohtake K, Maeno T, Ueda H, Ogihara M, Natsume H, Morimoto Y. Poly-L-arginine enhances paracellular permeability via serine/threonine phosphorylation of ZO-1 and tyrosine dephosphorylation of occludin in rabbit nasal epithelium. Pharm Res. 2003;20:1838–1845. doi: 10.1023/b:pham.0000003383.86238.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoo J, Nichols A, Mammen J, Calvo I, Song JC, Worrell RT, Matlin K, Matthews JB. Bryostatin-1 enhances barrier function in T84 epithelia through PKC-dependent regulation of tight junction proteins. Am J Physiol. 2003;285:C300–C309. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00267.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hirase T, Kawashima S, Wong EYM, Ueyama T, Rikitake Y, Tsukitai S, Yokoyama M, Staddon JM. Regulation of tight junction permeability and occludin phosphorylation by RhoA-p160ROCK-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:10423–10431. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007136200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Y, Zhang J, Yi XJ, Yu FSX. Activation of ERK1/2 MAP kinase pathway induces tight junction disruption in human corneal epithelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 2004;78:125–136. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson LN, De Moliner E, Brown NR, Song H, Barford D, Endicott JA, Noble ME. Structural studies with inhibitors of the cell cycle regulatory kinase cyclin-dependent protein kinase 2. Pharmacol Ther. 2002;93:113–124. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(02)00181-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Senderowicz AM. Novel direct and indirect cyclin-dependent kinase modulators for the prevention and treatment of human neoplasms. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2003;52:S61–S73. doi: 10.1007/s00280-003-0624-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang C, Kazanietz MG. Divergence and complexities in DAG signaling: looking beyond PKC. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2003;24:602–608. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DeMaio L, Chang YS, Gardner TW, Tarbell JM, Antonetti DA. Shear stress regulates occludin content and phosphorylation. Am J Physiol. 2001;281:H105–H113. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.1.H105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Atkinson KJ, Rao RK. Role of protein tyrosine phosphorylation in acetaldehyde-induced disruption of epithelial tight junctions. Am J Physiol. 2001;280:G1280–G1288. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.280.6.G1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kale G, Naren AP, Sheth P, Rao RK. Tyrosine phosphorylation of occludin attenuates its interactions with ZO-1, ZO-2, and ZO-3. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;302:324–329. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00167-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gorodeski GI, Pal D. Involvement of estrogen receptors α and β in the regulation of cervical permeability. Am J Physiol. 2000;278:C689–C696. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.4.C689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Medina R, Rahner C, Mitic LL, Anderson JM, Van Itallie CM. Occludin localization at the tight junction requires the second extracellular loop. J Membr Biol. 2000;178:235–247. doi: 10.1007/s002320010031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsukita S, Furuse M, Itoh M. Multifunctional strands in tight junctions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:285–293. doi: 10.1038/35067088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wong V, Gumbiner BM. A synthetic peptide corresponding to the extracellular domain of occludin perturbs the tight junction permeability barrier. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:399–409. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.2.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.