The evolution of olefin metathesis into a reaction routinely used to form new carbon–carbon double bonds has been enabled by the development of well-defined transition-metal catalysts.[1,2] Many metathesis catalysts based on the [L2X2Ru=CHR] scaffold have been synthesized in an effort to increase catalyst stability, activity, and substrate scope.[3–10] A significant gain in these areas was achieved after exchanging a single PCy3 ligand of 1 with H2IMes (H2IMes = 1,3-dimesityl-4,5-dihydroimidazol-2-ylidene),an N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC), to produce catalyst 2 (Figure 1).[5] These results are attributed to the increased σ-donor ability of H2IMes over PCy3, which increases the affinity for π-acidic olefins relative to σ-donating phosphines.[11] Additionally, exchange of the remaining PCy3 ligand with a chelating ether moiety provides a more stable complex, catalyst 3.[6]

Figure 1.

Commonly utilized ruthenium olefin metathesis catalysts. Cy = cyclohexyl.

Recently, the synthesis of cyclic (alkyl)(amino)carbenes (CAACs), in which one amino group from an NHC has been replaced by an alkyl group, was reported.[12] The greater σ-donor ability of carbon versus nitrogen results in more electron-donating ligands, as indicated by the vCO absorption of cis-[Rh(Cl)(CO)2L] complexes (L = H2IMes, , 2081 cm−1; L = 5b, , 2077 cm−1).[13] The exchange of an sp2-hybridized nitrogen atom for an sp3-hybridized carbon atom also changes the steric environment relative to NHCs. Although most NHCs are C2v-symmetric, the CAACs reported to date are Cs- or C1-symmetric, which may have implications for the microscopic reversibility of the olefin-binding and cycloreversion steps in the metathesis catalytic cycle.[14,15] The unique properties of CAACs led us to explore the utility of this new class of stable carbenes as ligands in olefin metathesis catalysts.

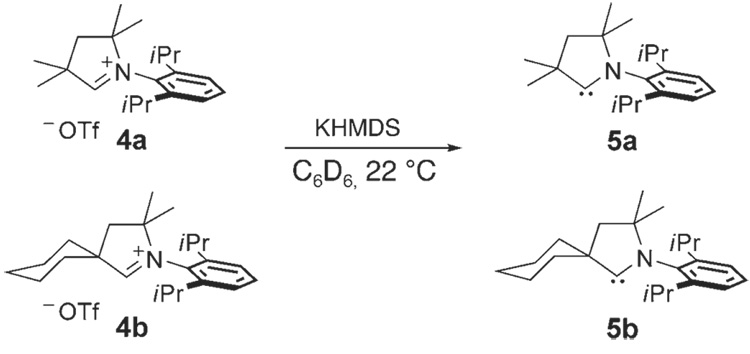

We first chose to investigate carbenes 5a,b, which can be prepared from their respective salts 4a,b (Scheme 1).[12, 16] These ligands each contain an N-DIPP (DIPP = 2,6-diisopro-pylphenyl) group and vary the steric bulk at the quaternary carbon adjacent to the carbene center, with either two Me groups (5a) or a spiro-fused cyclohexyl group (5b). Upon addition of potassium hexamethyldisilazide (KHMDS) to salts 4a,b at 22°C in benzene, the corresponding carbenes 5a,b are obtained in good conversion as observed by 1H NMR spectroscopy.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of carbenes 5a,b.

Ruthenium olefin metathesis catalysts bearing a pyridine ligand typically undergo facile ligand exchange with stronger donors such as phosphines or NHCs.[17] Thus, upon addition of pyridine complex 6[18] to an NHC, the resulting ruthenium complex is typically coordinated by a carbene ligand and a phosphine ligand (e.g. 2), rather than a pyridine ligand. However, upon treatment of pyridine complex 6 with carbenes 5a,b (generated in situ), no evidence for the expected phosphine complexes was obtained by 1H or 31P NMR spectroscopy [Eq. (1)]. Instead, air-sensitive pyridine adducts 7a,b were isolated in modest yields.

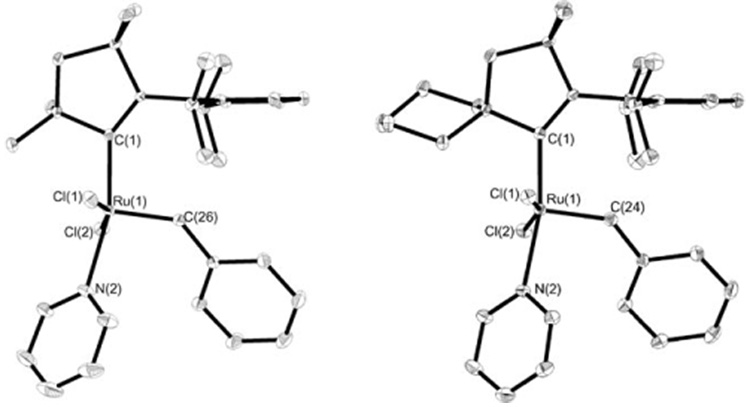

X-ray crystallographic analysis of compounds 7a,b was conducted. These complexes exhibit a distorted square-pyramidal geometry with the benzylidene ligand in the apical position (Figure 2). The bond lengths and angles of the pyridine catalysts 7a,b are similar to those of [(H2IMes)(py)2(Cl)2Ru=CHPh] (8) (see the Supporting Information).[17] The Ru–Ccarbene distance is ≈ 0.05 Å shorter than in 8 which is consistent with the increased σ-donating ability of CAACs relative to H2IMes. In addition, the Ru–Cbenzylidene bond length is ≈ 0.03 Å shorter in 7a,b than in 8, possibly a result of the trans influence of the additional pyridine ligand in 8.

Figure 2.

X-ray crystal structures of 7a (left) and 7b (right). Thermal ellipsoids are drawn at 50% probability and hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity.

The efficiency of catalysts 7a,b was examined in the ring-closing metathesis of diethyl diallylmalonate (9) [Eq. (2)].  Maximum conversions to cyclopentene 10 observed by 1H NMR spectroscopy were less than 50% after 24 h at 22°C or 60°C, which is attributed to catalyst decomposition. These results are consistent with those obtained previously with pyridine-containing catalysts.[19] For comparison, complexes 2 and 3 can achieve 95% conversion to 10 in 30 and 20 min, respectively, at 30°C and 1 mol % catalyst loading.[19]

Maximum conversions to cyclopentene 10 observed by 1H NMR spectroscopy were less than 50% after 24 h at 22°C or 60°C, which is attributed to catalyst decomposition. These results are consistent with those obtained previously with pyridine-containing catalysts.[19] For comparison, complexes 2 and 3 can achieve 95% conversion to 10 in 30 and 20 min, respectively, at 30°C and 1 mol % catalyst loading.[19]

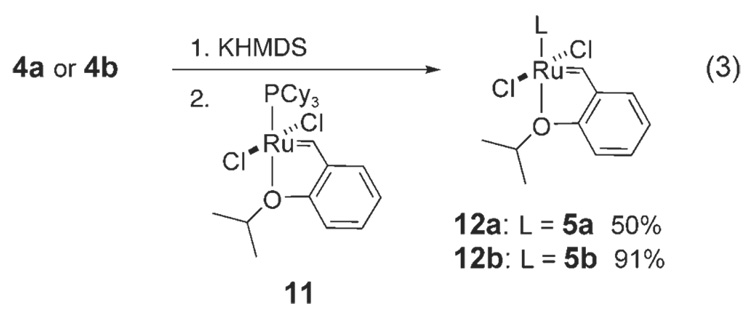

To obtain more stable complexes, we targeted complexes 12a,b. After addition of 5 a,b (prepared in situ) to ruthenium precursor 11,[8] catalysts 12a,b were isolated and purified in good yields by column chromatography [Eq. (3)]. Chelating ether complexes 12a,b are air- and moisture-stable compounds.

Similar to complexes 7a,b, the solid-state structures of 12a,b show a distorted square-pyramidal structure with the benzylidene moiety at the apical position (Figure 3). Comparing complexes 12 a,b with the H2IMes-containing analogue 3, the Ru–Ccarbene distances are ≈ 0.04–0.05 Å shorter and the Ru–O distances are 0.04–0.09 Å longer than in complex 3 (see the Supporting Information).[6] These observations are consistent with the increased σ-donating properties of ligands 5 a,b over their NHC counterparts.

Figure 3.

X-ray crystal structures of 12a (left) and 12b (right). Thermal ellipsoids are drawn at 50% probability and hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity.

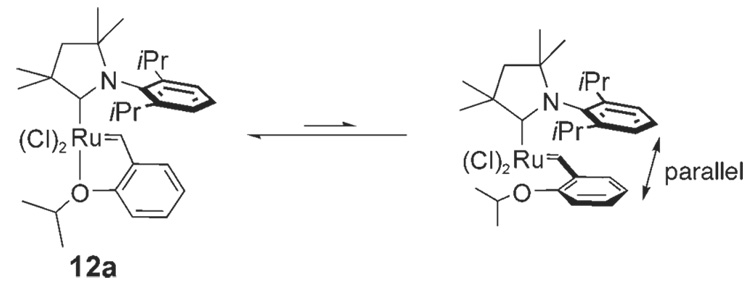

In all solid-state structures obtained, the CAAC exhibits the same orientation relative to the benzylidene group (Figure 4). The N-aryl ring is located above the benzylidene moiety, while the quaternary carbon adjacent to the carbene center is positioned over an empty coordination site. In the case of pyridine complexes 7a,b, this observed preference may be due to π–π stacking between the N-aryl ring and the benzylidene ring. For chelating ether complexes 12a,b this structural preference may be a result of negative steric interactions between the Me groups on the quaternary carbon adjacent to the carbene carbon and the benzylidene proton (Figure 4). From this side view, it is apparent that the benzylidene proton would be in close contact with one Me group on the quaternary carbon center if the ligand were rotated 180° relative to the remainder of the molecule.

Figure 4.

View of complex 12a looking down the Ru=CHR bond. It can be observed that rotating the carbene 180° would place the protons on the benzylidene and Me group on the quaternary carbon center in close proximity.

1H NMR spectroscopy data suggest that the solid-state conformation of 12a,b is maintained in solution. 2D-ROESY experiments performed on complexes 12 a,b in C6D6 at 22 °C demonstrate Overhauser effects between the benzylidene resonance and the aryl protons on the N-DIPP moiety, the equivalent methine resonances of the aryl isopropyl groups, and the enantiotopic Me groups facing the benzylidene proton (Figure 4b). Overhauser effects are not observed between the benzylidene proton and the gem-dimethyl(ene) groups adjacent to the carbene center. This interaction might be expected if there is fast exchange between two orientations of the carbene ligand relative to the ruthenium benzylidene.

The efficiency of catalysts 12a,b was examined in the ring-closing metathesis of 9, 13a, and 13b [Eq. (4)]. At a catalyst  loading of 1 mol% catalyst loading, chelating ether catalysts 12a,b achieved 97% and 95% conversion of diethyl diallyl-malonate (9) after heating at 60 °C for 3.3 h and 10 h, respectively. Uninitiated catalyst is observed for both catalysts even at high conversions, indicating that only a fraction of added catalyst is engaged in the reaction. Catalyst 12a converts 13a to 95% of trisubstituted olefin 14a in 20 h at 60°C, whereas catalyst 12b achieves 96% conversion after 48 h at 60°C. However, catalysts 12a,b showed no reactivity in the conversion of 13b to tetrasubstituted olefin 14b.

loading of 1 mol% catalyst loading, chelating ether catalysts 12a,b achieved 97% and 95% conversion of diethyl diallyl-malonate (9) after heating at 60 °C for 3.3 h and 10 h, respectively. Uninitiated catalyst is observed for both catalysts even at high conversions, indicating that only a fraction of added catalyst is engaged in the reaction. Catalyst 12a converts 13a to 95% of trisubstituted olefin 14a in 20 h at 60°C, whereas catalyst 12b achieves 96% conversion after 48 h at 60°C. However, catalysts 12a,b showed no reactivity in the conversion of 13b to tetrasubstituted olefin 14b.

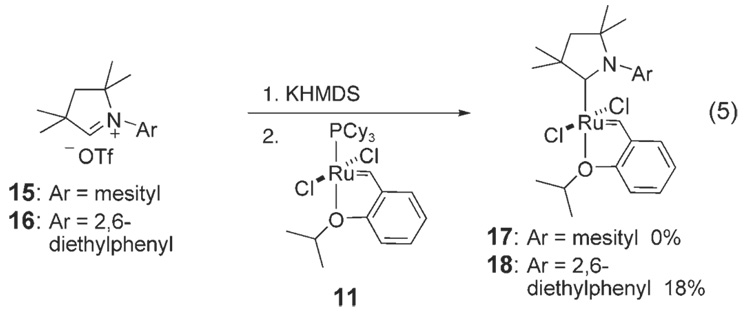

We hypothesized that sterics could be responsible for the lower activity of catalysts 12a,b relative to 2 and 3. CAACs without the quaternary carbon center adjacent to the carbene carbon are not synthetically accessible; thus, decreasing the steric bulk of the N-aryl ring was targeted. Both the N-mesityl- and N-DEP (DEP=2,6-diethylphenyl)-substituted salts, 15 and 16, respectively, were synthesized; deprotonation of 15 and 16 under a variety of conditions did not afford the desired free carbenes [Eq. (5)]. In situ deprotonations of 15 and 16 with KHMDS at −78 °C in THF in the presence of ruthenium precursor 11 were also attempted. Although 17 was not observed by NMR spectroscopy, complex 18 could be  observed and isolated. Similar to 12a,b, complex 18 is an air-and moisture-stable solid. X-ray diffraction studies of catalyst 18 show similar bond lengths and angles to those in 12 12a,b (Figure 5).

observed and isolated. Similar to 12a,b, complex 18 is an air-and moisture-stable solid. X-ray diffraction studies of catalyst 18 show similar bond lengths and angles to those in 12 12a,b (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

X-ray crystal structure of 18. Thermal ellipsoids are drawn at 50% probability and hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity.

Catalyst 18, which differs from 12a only by replacement of N-DIPP with N-DEP, demonstrates significantly increased activity in the formation of di- and trisubstituted olefins. In the presence of 1 mol% 18, 95% conversion of 9 to substituted cyclopentene 10 is observed in 15 min at 30 °C, as compared to 3 h at 60°C required for catalyst 12a (Table 1). Catalyst 18 achieves 95% conversion of 13a to trisubstituted cyclopentene 14a at 30 °C in 1 h, which is comparable to the performance of catalysts 2 and 3. However, catalyst 18 showed no reactivity in the conversion of 13b to 14b.

Table 1.

Comparison of the activities of catalysts 12a, 12b, 18, 2, and 3.

| Catalyst | Conversion (9→10) | Conversion (9→14b) |

|---|---|---|

| 12a | 97% (3.3 h at 60 °C) | 95% (20 h at 60 °C) |

| 12b | 95% (10 h at 60 °C) | 96% (48 h at 60 °C) |

| 18 | 95% (15 min at 30 °C) | 95% (1 h at 30 °C) |

| 2 | 95% (30 min at 30 °C) | 95% (45 min at 30 °C) |

| 3 | 95% (20 min at 30 °C) | 95% (45 min at 30 °C) |

The dramatic increase in activity observed after slightly decreasing the steric bulk of the N-aryl group is attributed to catalyst initiation. We postulate that catalyst initiation requires dissociation of the ether moiety and rotation of the benzylidene ring into a plane parallel to the N-aryl group to open a coordination site for incoming olefin. [20] For complexes 12a,b this process may be sterically unfavorable, thus resulting in poor initiation (Figure 6). The steric bulk of the ortho-aryl substituents may have a significant effect on initiation for two reasons. First, the Ru–Ccarbene bond length is slightly shorter than in NHC analogues, thus bringing the aryl ring in closer proximity to the ruthenium center. Second, the quaternary carbon adjacent to the N-aryl group restricts rotation around the N-aryl bond and the Caryl–CiPr bond, as indicated by NMR spectroscopy experiments discussed earlier.

Figure 6.

Proposed rotation required for catalyst initiation.

Interestingly, replacement of the N-mesityl groups in complex 3 with N-DIPP groups,[21] results in a catalyst with increased activity for the ring-closing metathesis of 9 (97% conversion in 13 min vs. 20 min).[20] However, this bulkier catalyst differs from the CAAC complexes owing to the absence of substitution at the carbon adjacent to the nitrogen atom.

Our investigation of the use of CAACs as ligands for olefin metathesis catalysts has shown promising results. By tuning the steric bulk of the N-aryl group, the results of ring-closing metathesis for the formation of di- and trisubstituted olefins are comparable to those achieved with standard catalysts 2 and 3.

Footnotes

Lawrence M. Henling and Dr. Michael Day are acknowledged for X-ray crystallographic analysis. D.R.A. acknowledges NSF and NDSEG predoctoral fellowships. D.J.O. thanks the Mellon Foundation for financial support. R.H.G. and G.B. were supported by the NSF (CHE-0410425) and the NIH (R01 GM 68825).

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.

References

- 1.Grubbs RH. Handbook of Metathesis. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ivin KJ, Mol JC. Olefin Metathesis and Metathesis Polymerization. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwab P, Grubbs RH, Ziller JW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:100–110. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nguyen ST, Grubbs RH, Ziller JW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:9858–9859. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scholl M, Ding S, Lee CW, Grubbs RH. Org. Lett. 1999;1:953–956. doi: 10.1021/ol990909q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garber SB, Kingsbury JS, Gray BL, Hoveyda AH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:8168–8179. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yun J, Marinez ER, Grubbs RH. Organometallics. 2004;23:4172–4173. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Despagnet-Ayoub E, Grubbs RH. Organometallics. 2005;24:338–340. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berlin JM, Campbell K, Ritter T, Funk TW, Chlenov A, Grubbs RH. Org. Lett. 2007;9:1339–1342. doi: 10.1021/ol070194o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stewart IC, Ung T, Pletnev AA, Berlin JM, Grubbs RH, Schrodi Y. Org. Lett. 2007;9:1589–1592. doi: 10.1021/ol0705144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanford MS, Love JA, Grubbs RH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:6543–6554. doi: 10.1021/ja010624k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lavallo V, Canac Y, Prasang C, Donnadieu B, Bertrand G. Angew. Chem. 2005;117:5851–5855. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:5705–5709. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lavallo V, Canac Y, DeHope A, Donnadieu B, Bertrand G. Angew. Chem. 2005;117:7402–7405. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:7236–7239. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cavallo L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:8965–8973. doi: 10.1021/ja016772s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romero PE, Piers WE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:1698–1704. doi: 10.1021/ja0675245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jazzar R, Rian D, Bourg J-B, Donnadieu B, Canac Y, Bertrand G. Angew. Chem. 2007;119:2957–2960. doi: 10.1002/anie.200605083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:2899–2902. doi: 10.1002/anie.200605083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanford MS, Love JA, Grubbs RH. Organometallics. 2001;20:5314–5318. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dias EL. PhD Thesis. Pasadena CA (USA): California Institute of Technology; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ritter T, Hejl A, Wenzel AG, Funk TW, Grubbs RH. Organometallics. 2006;25:5740–5745. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hejl AH. PhD Thesis. Pasadena, CA (USA): California Institute of Technology; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Courchay FC, Sworen JC, Wagener KB. Macromolecules. 2003;36:8231–8239. [Google Scholar]