Abstract

Structurally diverse ligands were studied in A3 adenosine receptor (AR)-mediated β-arrestin translocation in engineered CHO cells. The agonist potency and efficacy were similar, although not identical, to their G protein signaling. However, differences have also been found. MRS542, MRS1760, and other adenosine derivatives, A3AR antagonists in cyclic AMP assays, were partial agonists in β-arrestin translocation, indicating possible biased agonism. The xanthine 7-riboside DBXRM, a full agonist, was only partially efficacious in β-arrestin translocation. DBXRM was shown to induce a lesser extent of desensitization compared with IB-MECA. In kinetic studies, MRS3558, a potent and selective A3AR agonist, induced β-arrestin translocation significantly faster than IB-MECA and Cl-IB-MECA. Non-nucleoside antagonists showed similar inhibitory potencies as previously reported. PTX pretreatment completely abolished ERK1/2 activation, but not arrestin translocation. Thus, lead candidates for biased agonists at the A3AR have been identified with this arrestin-translocation assay, which promises to be an effective tool for ligand screening.

Keywords: purines, G protein-coupled receptors, arrestin, adenosine, agonists, antagonists

1. INTRODUCTION

Arrestins are a family of four cytoplasmic scaffolding proteins primarily responsible for dual roles in inactivating the signaling ability of a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) following the binding of an agonist and in modulating intracellular signaling [1,2]. There are four isoforms of arrestins. Arrestin1 and arrestin4 are only expressed in the visual transduction system. Arrestin2 (β-arrestin1) and arrestin3 (β-arrestin2) are expressed ubiquitously in the body. Arrestins translocate and bind to an activated GPCR that has been phosphorylated by a G protein-coupled receptor kinase (GRK). It has been suggested that arrestins bind to phosphorylated sites on an intracellular loop of the GPCR to prevent its association with the Gα subunit [3]. Consequently, the G protein-dependent signaling is terminated. Additionally, arrestins act as scaffold proteins linking the GPCR to internalization proteins such as clathrin. The GPCRs are either recycled to the cell surface or degraded in the lyzosomes after moving to the clathrin pits for endocytosis. Recent evidence has shown that arrestins can also function to activate signaling cascades independently of G protein activation [1]. The ubiquitination of β-arrestin has been shown to be dispensable for the cytosol-to-membrane transition, but essential for the formation of a tight complex with the GPCR [2]. The ability of arrestin to modulate ERK activation, an important signal in cellular survival and proliferation, has been linked to this ubiquitination.

The A3 adenosine receptor (AR) is an important target for a number of inflammatory, neoplastic, and neurodegenerative conditions [4–7]. Both agonists and antagonists [8] are of potential clinical application. The selective A3AR agonists IB-MECA and Cl-IB-MECA are currently in clinical trials for the autoimmune inflammatory disease rheumatoid arthritis and cancer, respectively [5,6]. We have previously studied G protein-mediated signaling after agonist binding to the A3AR. It was found that some adenosine derivatives, previously assumed to be full AR agonists, are partial agonists or antagonists at the A3 subtype [9]. It is important to know how these agonists and antagonists behave in A3AR-mediated pathways that are independent of G proteins, such as arrestin. The A3AR has been reported to be a rapidly desensitizing receptor [10,11], and receptor regulation appears to be important in the clinical actions of A3AR agonists [12]. GRKs have been suggested to be involved in the desensitization and internalization process. However, it has been reported that the arrestin-translocation was not observed following the activation of the rat A3AR endogenously expressed in the RBL-2H3 cells [13]. Previously, it was not clear if the human A3AR couples to arrestins.

In order to test whether the human A3AR can induce arrestin translocation and how the known A3AR agonists and antagonists behave, a PathHunter™ cell line engineered for human β-arrestin translocation in response to A3AR activation was utilized [14]. The focus of this paper is both to demonstrate the utility in drug screening of a cell line engineered for detecting arrestin translocation and to identify ligands that show biased agonism. The response was initially measured in a 96-well, and later a 384-well plate format with detection through a luminescent reaction based on enzyme fragment complementation [15]. A bioactive chemical library [16] was selected for this purpose. This study takes into consideration that a given agonist may have differential functional effects on multiple signaling pathways downstream of the A3AR. Since multiple pathways may be involved in the clinically relevant action of A3 agonists, it would be important to identify biased agonists that favor one pathway over another for use as pharmacological tools and potential leads for therapeutic agents.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Materials

NECA (adenosine-5′-N-ethyluronamide), CCPA (2-chloro-N6-cyclopentyladenosine), Cl-IB-MECA (2-chloro-N6-(3-iodobenzyl)adenosine-5′-N-methyluronamide), adenosine and inosine were from Sigma (MO, USA). LUF6000 (N-(3,4-dichloro-phenyl)-2-cyclohexyl-1H-imidazo[4,5-c]quinolin-4-amine) was synthesized as described at Leiden/Amsterdam Center for Drug Research (Leiden, The Netherlands) [17]. Compound 20 [18] was synthesized by Liesbet Cosyn and Prof. Serge Van Calenbergh at Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium. MRS 541 (N6-(3-iodobenzyl)adenosine), MRS 542 (2-chloro-N6-(3-iodobenzyl)adenosine), and (N)-methanocarba derivatives of adenosine [9,19] were synthesized at NIDDK, National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD, USA). Other receptor ligands were contained in a previously assembled chemical library at the same location [16]. Calcium and membrane potential assay kits were from Molecular Devices (Sunnyvale, CA, USA). [3H]cyclic AMP (40 Ci/mmol) was from Amersham (Buckinghamshire, UK). The PathHunter™ reagent detection kit was from DiscoveRx (Fremont, CA).

2.2. β-Arrestin translocation assay

The β-Arrestin translocation assay was performed using a PathHunter™ β-arrestin assay kit from DiscoveRx (Fremont, CA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cells were manufactured to express the human A3AR and were used as a pool (CHO-ADORA3). Briefly, PathHunter CHO cells expressing the A3AR and arrestin were grown in 96- or 384-well plates for 24 h in Hank’s F-12 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 Units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 2 μmol/ml glutamine. Cells were treated with agonists for 60 min. For the test of antagonists, cells were treated with one of these agents for 20 min before the addition of the agonist and then incubated for an additional 60 min. Cells were then treated with detection reagents (mixture of 1 part Galacton Star substrate with 5 parts Emerald II TM Solution, and 19 parts of PathHunter Cell Assay Buffer) and incubated at room temperature for an additional 60 min before luminescence was measured. Luminescence was quantified in a 384-well plate format using a LJL Analyst plate reader (LJL Biosystems, Sunnyvale, CA). When applicable, pertussis toxin (PTX, 200 ng/ml) was incubated with cells for 24 h before the measurement. For the kinetic study, the agonists were added at various time points, and the reaction was terminated by the addition of the mixture of detection reagents.

2.3 ERK1/2 activation assay

The pERK1/2 was quantitively determined using pERK1/2 TiterZyme® enzyme immunometric assay (EIA) kit (Assay Designs, Inc., Ann Arbor, MI). In brief, CHO-ADORA3 Pathhunter cells in 24-well tissue culture plates were treated with an A3AR agonist MRS3558 (1 μM) for 2–60 min followed by washing with ice-cold PBS and lysis in 0.2 ml RIPA cell lysis buffer. The cell lysates were diluted 1:10 with the assay buffer and 0.1 ml of the diluted lysates were applied to the 96-well plate coated with monoclonal antibody to phosphorylated ERK1/2 and incubated at room temperature for 60 min with shaking. The plate was washed four times with wash buffer and incubated with a rabbit polyclonal antibody to pERK (which binds to the captured antibody to pERK in the plate) at room temperature for 60 min. After incubation and shaking for 60 min, the excessive antibody was washed out, the plate was incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (binding to the rabbit polyclonal antibody) for 30 min. After washing, 0.1 ml of substrate solution containing 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine and hydrogen peroxide were added to each well, and the plate was incubated for another 30 min. The reaction was stoped by 1 N HCl, and the OD values were measured at 450 nm. The OD values were converted to actual pERK concentrations (pg/ml) based on the standard curve of the recombinant pERK standards provided in the kit. For the desensitization studies [20,21], cells were incubated with agonists at 37°C for 24 h. The medium was then replaced with agonist-free medium and cells were treated with an A3AR agonist MRS3558 at various time points.

2.4. Cyclic AMP accumulation assay

CHO cells expressing the recombinant human A3AR [22] were cultured in DMEM and F12 (1:1) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 Units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 2 μmol/ml glutamine. Intracellular cyclic AMP levels were measured with a competitive protein binding method. CHO cells that expressed the recombinant human A3AR were plated in 24-well plates in 0.5 ml medium. After 24 hr, the medium was removed and cells were washed three times with 1 ml DMEM, containing 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4. Cells were treated with agonists and were then incubated for 30 min in the presence of rolipram (10 μM) and adenosine deaminase (3 Units/ml). Forskolin (10 μM) was then added to the medium, and incubation was continued for an additional 15 min. The reaction was terminated upon removal of the supernatant, and the cells were lysed upon the addition of 200 μl of 0.1 M ice-cold HCl. The cell lysate was resuspended and stored at −20°C. For determination of cyclic AMP production [23], protein kinase A (PKA) was incubated with [3H]cyclic AMP (2 nM) in K2HPO4/EDTA buffer (K2HPO4, 150 mM; EDTA, 10 mM), 20 μl of the cell lysate, and 30 μL 0.1 M HCl or 50 μl of cyclic AMP solution (0–16 pmol/200 μl for the standard curve). Bound radioactivity was separated by rapid filtration through Whatman GF/C filters and washed once with cold buffer. Bound radioactivity was measured by liquid scintillation spectrometry.

2.5. Intracellular calcium mobilization assay

CHO cells stably expressing the human A3AR were grown overnight in 100 μl of media in 96-well flat bottom plates at 37°C at 5% CO2 or until approx. 90% confluency. The calcium or membrane potential assay kit (Molecular Devices) was used as directed without washing cells, and with probenecid added to the loading dye at a final concentration of 2.5 mM to increase dye retention. Cells were incubated with 50 μl dye/probenecid for 60 min at room temperature. The compound plate was prepared using dilutions of various compounds in Hanks Buffer. Samples were run in duplicate using a Flexstation (Molecular Devices) at room temperature. Cell fluorescence (Excitation = 485 nm; Emission = 525 nm) was monitored following exposure to the compound. Increases in intracellular calcium are reported as the maximum fluorescence value after exposure minus the basal fluorescence value before exposure.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Functional parameters were calculated using Prism 4.0 software (GraphPAD, San Diego, CA, USA). Data were expressed as mean ± SD. A Schild analysis of the antagonist data was carried out as described [24]. Statistical significance was determined by ANOVA or t-test (p<0.05 was considered statistically significant).

3. RESULTS

The assay method for arrestin translocation consists of an engineered PathHunter cell system. The chemiluminescent signal is dependent on the proximity of two fragments of beta-galactosidase, one of which (termed the enzyme acceptor) is fused to the human β-arrestin2 protein and the other (termed the ProLink tag) is fused to the C-terminus of the GPCR. When arrestin translocates to its natural binding site on the GPCR, the two inactive fragments form an active complex that converts an exogenously delivered substrate to a detectable signal. The cell line we used was engineered to express the human A3AR fusion protein, and the resulting luminescent-responsive cell pool was used in our studies. Signal can only be generated from the exogenously expressed ProLink tagged receptor.

We first tested the robustness and reproducibility of the response in this engineered cell line. We examined the potency and efficacy (intrinsic activity) in arrestin translocation of several AR agonists widely used as pharmacological probes, NECA 1 (nonselective), CPA 2 (A1 selective), CGS21680 3 (human A2A and A3 selective), and Cl-IB-MECA 4(A3 selective). It was demonstrated that all four agonists are fully efficacious at the A3AR as indicated by the translocation of human β-arrestin (Figure 1). The rank order of their potencies at the A3AR was Cl-IB-MECA > NECA > CGS21680 ≥ CPA, which is similar to that obtained in binding and cyclic AMP functional assays [25,26].

Figure 1.

Concentration-response curves in the β-arrestin translocation assay for known synthetic AR pharmalogical probes (CPA 2, CGS21680 3, NECA 1, and Cl-IB-MECA 4) and the native nucleotide ligands (ADP 5, ATP 6) of various P2Y receptor subtypes. Results are expressed mean ± SEM from three separate experiments performed in duplicate.

We next tested the specificity of the engineered CHO cell line designed for β-arrestin signaling in response to A3AR activation. It is known that CHO cells endogenously express P2Y1, P2Y2, P2Y4 and P2Y6 receptors, which can be stimulated by agonists ADP 5(P2Y1), ATP 6 (P2Y2), UDP 7 (P2Y6) and UTP 8 (P2Y2 and P2Y4) [27]. However, ADP, ATP, UDP and UTP did not induce arrestin translocation in this cell line (Figure 1). In an additional control experiment, CHO cells were transfected with the human A3AR ProLink tag fusion protein but not the fusion protein containing the arrestin beta-galactosidase fragment (enzyme acceptor) that is an essential link in the luminescent reaction. AR agonists did not induce a detectable response in this cell preparation. Therefore, the response measured is dependent on arrestin translocation that is specifically mediated by the A3AR activation.

We then studied the efficacy within a bioactive chemical library assembled from a wide range of structurally diverse nucleoside and nonnucleoside derivatives shown previously to interact with the human A3AR [16]. Selected structures included in this chemical library are shown in Figure 2. Most of these compounds are highly potent at the A3AR; their affinity in binding assays at the A3AR has been reported previously [4,9,16,18,19,26,28–32]. The percent relative response can be used as an estimation of the Emax in this assay, an approach used successfully as a first approximation in the cyclic AMP assay [9,28]. Selected compounds were later studied in full concentration-response experiments (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Selected structures of ligands that were tested in the β-arrestin translocation assay using the CHO-ADORA3 Pathhunter cell line. A. Adenosine derivatives containing the natural riboside-like 5′-CH2OH group. B. NECA-like 5′-CONH-alkyl derivatives and ring-constrained (N)-methanocarba derivatives. C. Diverse structures that were shown previously to interact with the human A3AR.

Table 1.

Potency and relative effect (percent of the effect of a full agonist at 10 μM) of various AR ligands in inducing A3AR-mediated β-arrestin translocation.

| Compound | Arrestina | Cyclic AMPa | Bindinga | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potency pEC50 | Relative effect (%) | Potency pEC50 | Relative effect (%) | Affinity pKi | |

| Nucleoside A3AR agonists | |||||

| 1 NECA | 7.32 ± 0.13 | 100 ± 8 | 7.58 | 103 ± 6 | 7.46 |

| 2 CPA | 6.42 ± 0.16 | 88.6 ± 7.6 | 6.91 | 97 ± 4 | 7.14 |

| 3 CGS21680 | 6.67 ± 0.14 | 98.3 ± 11.0 | 6.62 | 98 ± 5 | 6.94 |

| 4 Cl-IB-MECA | 7.97 ± 0.14 | 102 ± 13 | 8.55 | 100 | 8.85 |

| 11 N6-MeAdo | ND | 80 ± 10 | ND | 96 ± 3 | 8.03 |

| 21 IB-MECA | 7.85 ± 0.16 | 100 ± 7 | 8.44 | 99 ± 6 | 8.74 |

| 26 MRS3558 | 8.26 ± 0.18 | 102 ± 4 | 9.42 | 103 ± 7 | 9.54 |

| 27 DBXRM | 6.33 ± 0.19 | 65.7 ± 13.4 | 6.08 | 96 ± 4 | 6.09 |

| Nucleoside A3AR partial agonists and antagonists | |||||

| 12 N6-Bn-Ado | ND | 33.4 ± 8.6 | ND | 55 ± 3 | 7.38 |

| 13 MRS541 | 7.73 ± 0.16 | 30.8 ± 1.6 | 7.07 | 46 ± 5 | 8.24 |

| 14 DPMA | ND | 24.3 ± 5.3 | NA | −1.7 ± 2.4 | 6.97 |

| 15 CCPA | 7.03 ± 0.29 | 47.4 ± 13.5 | NA | 0 | 7.42 |

| 16 MRS542 | 7.76 ± 0.10 | 31.2 ± 2.5 | NA | 0 | 8.74 |

| 17 | NA | 5.8 ± 4.4 | ND | 32.2 ± 3.5 | 6.44 |

| 18 | NA | 3 ± 5 | NA | 0 | 7.28 |

| 19 | NA | 1 ± 3 | ND | 12.7 ± 1.5 | 6.98 |

| 20 | ND | 8 ± 3 | ND | 41 ± 6 | 7.98 |

| 22 MRS3771 | NA | −1.7 ± 2.4 | NA | 0.5 ± 1.8 | 7.53 |

| 23 | ND | 17 ± 6 | 6.10 | 41 ± 5 | 6.45 |

| 24 MRS1743 | 6.48 ± 0.29 | 31.8 ± 6.6 | NA | 13 ± 1 | 8.04 |

| 25 MRS1760 | 6.02 ± 0.36 | 30.2 ± 7.4 | NA | 3 ± 2 | 8.72 |

| Endogenous nucleosides and nucleotides | |||||

| 5 ADP | NA | 5.6 ± 3.5 | NA | NA | NA |

| 6 ATP | NA | −5.8 ± 4.9 | NA | NA | NA |

| 7 UDP | NA | 1.9 ± 2.8 | NA | NA | NA |

| 8 UTP | NA | μ 2.6 ± 3.7 | NA | NA | NA |

| 9 Adenosine | 6.11 ± 0.13 | 95.9 ± 5.4 | 6.54b | 100 | 5.74c |

| 10 Inosine | ND | 32.5 ± 14.6 | ND | 15.9 ± 0.8 | < 5.0 |

| Nonnucleoside A3AR antagonists | |||||

| 28 MRS1191 | NA | 3 ± 2 | NA | NA | 7.50 |

| 29 MRS1220 | NA | 5.2 ± 4.3 | NA | NA | 9.22 |

| 30 MRS1523 | NA | −6 ± 5 | NA | NA | 7.72 |

| Atypical A3AR modulators | |||||

| 31 LUF5833 | 6.63 ± 0.23 | 46.1 ± 8.7 | ND | 84 ± 1d | 6.77d |

| 32 LUF6000 | NA | 5.2 ± 2.1 | NA | 1.7 ± 2.4 | < 5.0 |

For the arrestin assay (n = 3), the maximal effect of 10 μM NECA was expressed as 100%. For the adenylate cyclase assay (n = 3), the effect of 10 μM Cl-IB-MECA was expressed as 100%. Both NECA and Cl-IB-MECA are fully efficacious in these two assays. Binding affinity and cyclic AMP data are from references 9 and 28, unless otherwise noted. Values represent mean ± SEM.

ref. 40;

ref. 41;

ref. 26.

NA, not significantly active at 10 μM.

ND, not determined.

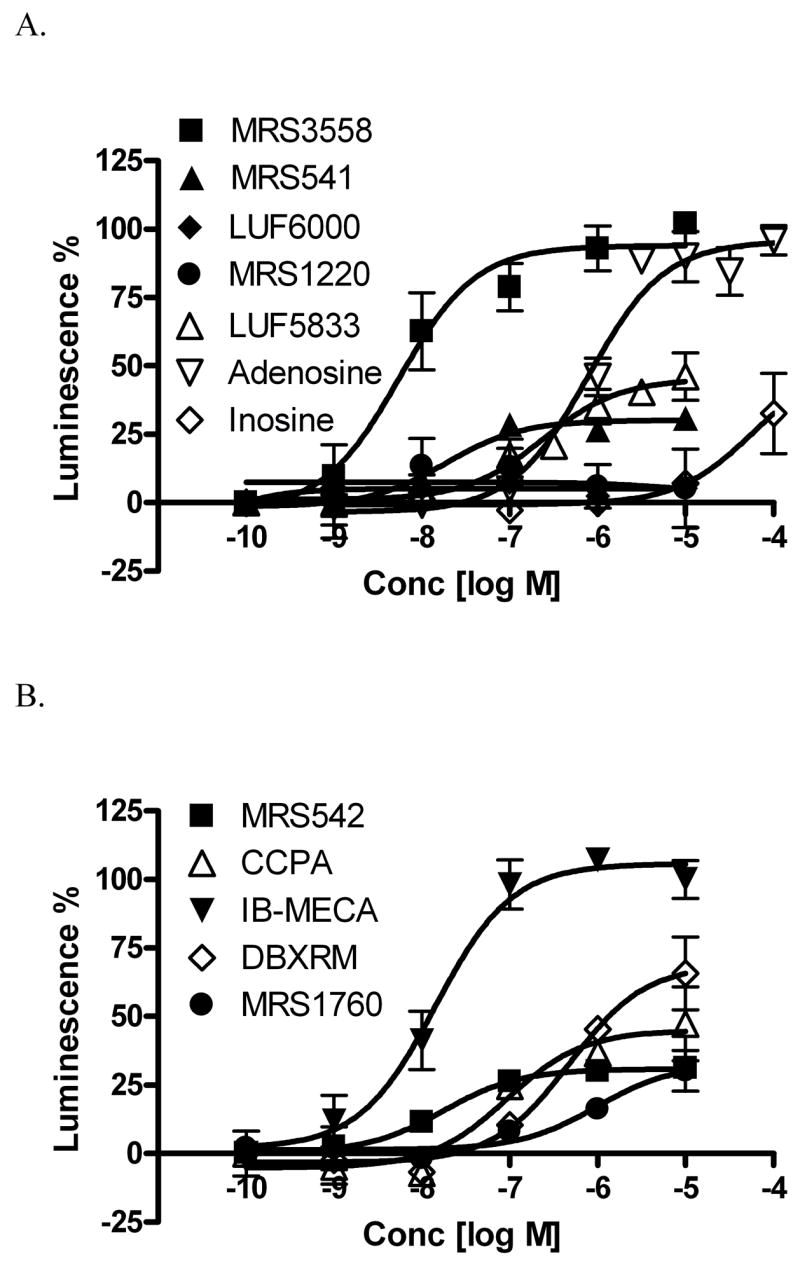

Concentration-response curves for selected structurally diverse A3AR modulators in the β-arrestin translocation assay are shown in Figure 3. It was found that both potency and efficacy values obtained in the arrestin translocation assay were often consistent with those determined in the cyclic AMP assay (Table 1, 15Figure 3A). However, differences were also found (Figure 3B). For example, CCPA , MRS542 16, and MRS1760 25, which have been reported as full antagonists in the cyclic AMP assay, were found to be partial agonists in the assay of arrestin translocation. DBXRM 27, previously shown to be a full agonist, was found to be only partially efficacious in the arrestin assay.

Figure 3.

Concentration-response curves for structurally diverse A3AR modulators in the β-arrestin translocation assay in the CHO-ADORA3 Pathhunter cell line. Results are expressed mean ± SEM from three separate experiments performed in duplicate.

The closely related N6 substituted derivatives of adenosine 12 (N6-benzyl) and 13 (N6-3-iodobenzyl) remained partial agonists in both assays. Compound 14 (DPMA), substituted at the N6 position with a sterically bulky group, and the doubly (N6/C2) substituted derivatives 15 (CCPA) and 16 (MRS542), were partial agonists with respect to arrestin. Compounds 14 – 16 all behaved as antagonists in the adenylate cyclase assay [9]. 2-Ether derivatives 17 – 19 [29] and the 2-triazolo derivative 20 [18] were weak or inactive in the arrestin assay, although several of these nucleosides were partial agonists with respect to adenylate cyclase. The native agonist adenosine 9 was a full agonist by both criteria, but its weakly binding metabolite inosine 10 displayed partial agonist activity, which was evident in both assays. The nucleoside derivative 22, an antagonist in the adenylate cyclase assay by virtue of the dimethylamide group [31], and nonnucleoside antagonists of the A3AR 28 – 30 [9] remained antagonists in the arrestin assay.

It has been reported that the A3AR is rapidly desensitized after exposure to agonists [33], and arrestin is responsible for desensitization of a large number of GPCRs. We then tested the kinetics of arrestin translocation caused by several prototypical AR agonists, NECA 1 and the A3AR-selective agonists IB-MECA 21, Cl-IB-MECA 4, and MRS3558 26 (Figure 4). All of these agonists are 5′-CONH-alkyl derivatives of adenosine, a modification that tends to preserve efficacy at both adenylate cyclase and arrestin pathways. One agonist (NECA) is unsubstituted at the N6 position and the others bear halo-substituted N6-benzyl groups. It was found that the rates of translocation of β-arrestin induced by NECA and the (N)-methanocarba derivative MRS3558 were significantly faster than those of IB-MECA and Cl-IB-MECA. The t1/2 values (calculated by One Phase Exponential Association built-in Prism) of the effects on arrestin translocation of IB-MECA (8.53 ± 2.26 min) or Cl-IB-MECA (7.62 ± 1.84 min) were significantly different from those of MRS3558 (1.80 ± 0.48 min) (p<0.05, ANOVA builtin Prism). Thus, differences between agonists that were not apparent in concentration-response curves were detectable by kinetic analysis.

Figure 4.

Kinetic analysis of four A3AR agonists in the β-arrestin translocation assay in the CHO-ADORA3 Pathhunter cell line. Results are expressed mean ± SEM from three separate experiments performed in duplicate.

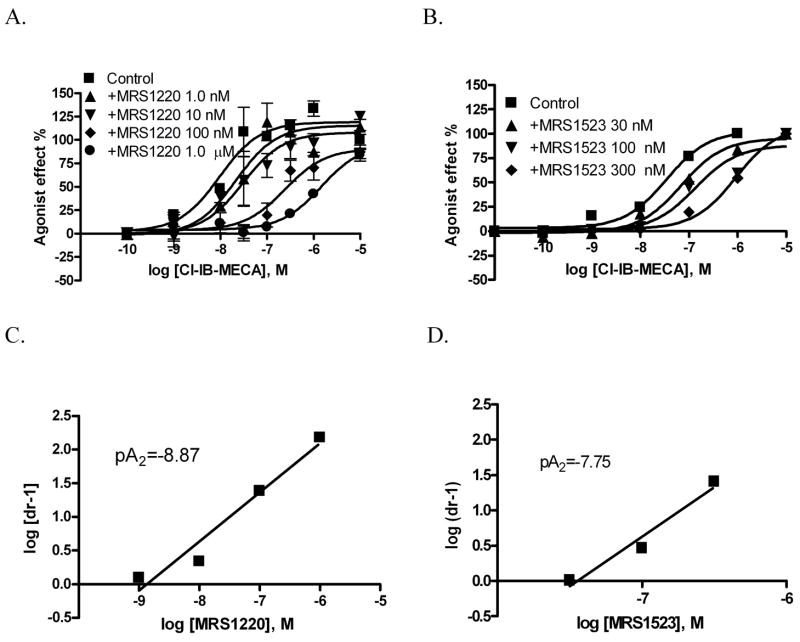

Two known nonnucleoside A3AR antagonists (Figure 5) were also characterized pharmacologically in the β-arrestin translocation assay. As described above, Cl-IB-MECA 4 induced the luminescence change indicative of arrestin translocation in a concentration-dependent manner. At fixed concentrations, two nonnucleoside A3AR antagonists, the triazoloquinazoline derivative MRS1220 29 and the pyridine derivative MRS1523 30, produced right shifts of the agonist response curves in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 5). A Schild analysis of the antagonism [24] provided pA2 values of 8.87 (29) and 7.75 (30), which are highly consistent with the human A3AR antagonism of these agent that was previously characterized in the adenylate cyclase system.

Figure 5.

Two nonnucleoside A3AR antagonists, the triazoloquinazoline derivative MRS1220 114 (A,C) and the pyridine derivative MRS1523 108 (B,D), characterized pharmacologically in the β-arrestin translocation assay in the CHO-ADORA3 Pathhunter cell line. Concentration response curves for the agonist Cl-IB-MECA 4 (A,B) and Schild analysis [19] of the antagonism was carried out (C,D). The Schild slopes were calculated to be 0.73 and 1.40 for C and D, respectively.

The A3AR is a Gi-coupled receptor, mediating inhibition of adenylyl cyclase, which is sensitive to pertussis toxin (PTX). Here we further tested the PTX-sensitivity of A3AR-mediated arrestin translocation. The arrestin concentration response curve for IB-MECA (10−10 to 10−5 M) was not affected by 24 h pretreatment with 200 ng/ml PTX (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Effect of PTX pretreatment (200 ng/ml) on β-arrestin translocation induced by IB-MECA. PTX was incubated with cells for 24 h before the measurement. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM from three experiments.

ERK1/2 activation induced by several GPCRs has been reported to be both G protein-dependent and –independent [34,35]. Here we explored if the A3AR-mediated ERK1/2 activation in the current assay system is G protein-dependent or arrestin-dependent. The high affinity A3AR agonist MRS3558 (1 μM) produced a marked increase in the activation of ERK1/2 (Figure 7A). Maximal activation was observed after approximately 5 min and then the activity slowly declined to basal levels. Pre-treatment with pertussis toxin (200 ng/ml) for 24 h completely abolished MRS3558-induced ERK1/2 activation.

Figure 7.

Studies of A3AR-mediated phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in the CHO-ADORA3 Pathhunter cell line. (A) Effects of pertussis toxin (PTX) pretreatment (24 h) on MRS3558 (1 μM)-induced activation of ERK1/2, and (B) pretreatment (24 h) with nucleosides IB-MECA and DBXRM desensitize the activation of ERK1/2. In each experiment, the maximal level of ERK1/2 activation was set to 100% and that observed in unstimulated to 0%. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n=3).

Although both DBXRM and IB-MECA are full agonists in an assay of cyclic AMP, DBXRM was shown to be a partial agonist in the arrestin translocation assay. We then tested if DBXRM and IB-MECA behave differently or not in inducing A3AR desensitization. Figure 7B shows that pretreatment of cells with both DBXRM and IB-MECA attenuated the maximal effect of MRS3558, but DBXRM shows a much lesser effect. The maximal agonist effects in the presence of IB-MECA (1 μM) and DBXRM (10 μM) were 21.0 ± 7.5% and 52.1 ± 7.9%, respectively, which are significantly different (p<0.05, Student’s test). Similarly, full agonists such as Cl-IB-MECA 4 were reported to be more efficacious than DBXRM inducing desensitization of rat A3AR with respect to its G protein-dependent pathway [20].

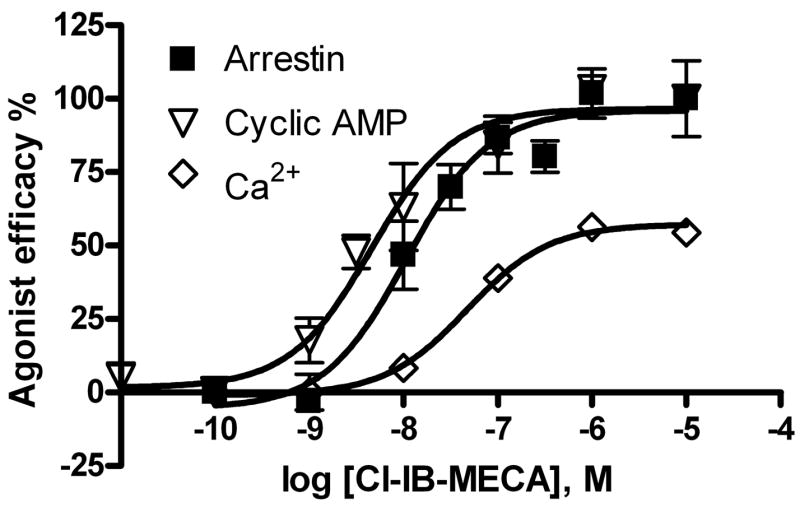

Finally, the potency and efficacy of one of the commonly used A3AR agonists, Cl-IB-MECA, at the arrestin signaling pathway was compared with those in other G protein-mediated signaling pathways (Figure 8). In various studies, A3AR activation has been noted to produce a rise in intracellular calcium [35]. Cl-IB-MECA, a full agonist in arrestin translocation and cAMP assays, was a partial agonist for calcium accumulation in the PathHunter™ cell line. In all cases the reference ligand against which the efficacy of Cl-IB-MECA was referenced is NECA.

Figure 8.

Comparison of the potency and efficacy of Cl-IB-MECA 4 at various A3AR-mediated signaling pathways. NECA was used a full agonist in all assays. The efficacy of NECA in each assay was expressed as 100%. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM of 3–5 separate experiments performed in duplicate or triplicate. The potency and Emax values from arrestin and cyclic AMP assays were listed in Table 1. The EC50 (nM) and Emax (compared with NECA) values of Cl-IB-MECA in the calcium assay are 47 ± 9 nM and 57± 6%, respectively.

4. DISCUSSION

The present study clearly demonstrates for the first time that the human A3AR mediates an arrestin translocation. Despite the artificial nature of in an engineered cell line used, this study suggests that different agonists of a given GPCR can selectively trigger certain effector pathways. The system allowed us to study agonist efficacy of a variety of nucleoside derivatives that have been previously shown to be A3AR agonists or antagonists. Comparison of different A3AR-mediated signaling pathways suggests that preferences exist in which pathway is activated by a given compound. Thus, this study provides the first evidence of possible biased agonism for this receptor subtype.

It should be noted that both the receptor and β-arrestin are likely to be over-expressed in the PathHunter cell line. The artificial nature of the system might affect A3AR-mediated arrestin translocation, and the findings may not translate when working with endogenously expressed receptors. Therefore, it would be worthwhile to examine arrestin translocation in cells endogenously expressing the A3AR and to confirm that the patterns of biased agonism observed in this study are maintained consistently. We have no explanation for the failure to detect arrestin translocation in RBL-2H3 cells, which are rat cells expressing an endogenous A3AR [13].

Differences in both maximal efficacy and kinetics were found in a comparison of responses in the arrestin and cyclic AMP assays. In some cases, a given compound is more efficacious in the adenylate cyclase system than in arrestin translocation (e.g. 17, 20, 23, and 31), and in other cases the preference is reversed (e.g. 14 – 16 and 25). Nucleosides previously determined to be antagonists of the human A3AR in a cyclic AMP assay were shown to activate the arrestin translocation. The (N)-methanocarba nucleoside derivative MRS3558, previously characterized as a potent and selective A3AR agonist, was found to induce the translocation of β-arrestin significantly faster than IB-MECA and Cl-IB-MECA. This could have relevance for the clinical use of A3AR agonists. If an arrestin-linked action of the receptor, for example ERK phosphorylation, is the desired mechanism of a given clinical activity, then there might be a preference for use of an agonist such as MRS3558 that appears to favor the arrestin pathway kinetically. As a practical application of this concept, the cytoprotective effects of MRS3558 in a traumatic injury model in the cat lung have been ascribed to ERK activation [36]. The agonist MRS3558 was more potent in protection in this model than was the agonist IB-MECA. Other differences between the cyclic AMP system and the arrestin system were found for xanthine-7-riboside derivatives, such as DBXRM. DBXRM was previously found to be a full agonist in a cyclic AMP functional assay [9], but was shown to be only partially efficacious in the arrestin-translocation assay. Interestingly, a further desensitization study suggested that DBXRM desensitizes the human A3AR to a lesser extent compared with IB-MECA, indicating that arrestin is likely involved in agonist-induced A3AR desensitization.

Among N6 substituted adenine 9-riboside (5′-CH2OH) derivatives that are potent A3AR ligands, the Emax observed in arrestin translocation is typically less than the Emax in the G protein-dependent pathway. Substitution of both 9-ribosides and (N)-methanocarba derivatives with a 5′-N-methyluronamide group provides full efficacy for a variety of analogues, in both arrestin and G protein-dependent pathways. However, 5′-N,N-dimethyluronamide derivatives, such as MRS3771 22, do not activate either pathway. An atypical agonist LUF5833 31 was reduced in efficacy in the arrestin pathway. Strikingly, nucleosides previously found to be antagonists in the adenylate cyclase system (in correlation with certain substitution of the N6 and C2 positions), such as the 9-ribosides MRS542 and CCPA and the (N)-methanocarba derivatives MRS1743 and 1760, were partial agonists in arrestin translocation. 9-Riboside derivatives substituted at the 2 position with sterically bulky groups, such as 17 and 20, tended to be more efficacious in the adenylate cyclase assay than in arrestin translocation. Xanthine derivatives and other nonnucleoside antagonists remained antagonists in arrestin translocation. It is intriguing to explore in future studies if MRS542 and other nucleoside antagonists can induce receptor internalization.

The concept of collateral efficacy implies that different agonists of a given GPCR can selectively induce certain effector pathways to different degrees, and thus, efficacy can be separated [37]. More specifically, the concept of β-arrestin-biased ligands has been described with examples for the β-adrenergic receptor [38]. The present findings with the A3AR are highly consistent with this concept. Cl-IB-MECA was shown to be a full agonist in causing both arrestin translocation and inhibition of cyclic AMP accumulation, whereas it is only partially efficacious in inducing calcium mobilization in this cell system.

It is interesting to note that although the A3AR-mediated Gi signaling pathway is PTX-sensitive, arrestin translocation was not removed by PTX treatment, suggesting a distinct signaling mechanism. It has been reported that ERK1/2 activation induced by several GPCRs can be both G protein-dependent and independent [34,39]. However, in this study the A3AR-mediated ERK1/2 activation seems to be PTX-sensitive and arrestin-independent.

In conclusion, we have the first indication of biased agonists for the A3AR using the PathHunter cell system as a screening tool. This system, although a genetically engineered cell line, was shown to be a robust, convenient, and reproducible technique for measuring the arrestin response to activation of the A3AR using a microplate luminescence reader. This method allows comparison of structure activity relationships with other second messenger assays to identify candidate compounds for possible biased agonism.

Our observation that there are differences in the G protein-dependent and independent processes associated with particular structural components of the ligands suggest a broad range of subsequent studies. In principle, if validated in tissues endogenously expressing the A3AR, these patterns of functional selectivity could be further accentuated through the rational design and synthesis of novel GPCR agonists. It will be useful now to try to reconcile the diverse physiological actions of A3AR ligands with particular signaling pathways. This effort will perhaps lead to the design of new agonists of the A3AR that display clearly delineated signaling preference. Our current medicinal chemical effort relating to the important clinical target of the A3AR is guided by these insights.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIDDK Intramural Research Program, National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD, USA). We thank Justin Mika, Dr. Vashti Lacaille, and Dr. Keith R. Olson of DiscoveRx Corp. (Fremont, CA) for helpful discussions. We thank Prof. Lak Shin Jeong (EWHA Womens Univ., Seoul, Korea), Liesbet Cosyn and Prof. Serge Van Calenbergh (Ghent Univ., Ghent, Belgium), Prof. Ad P. IJzerman (Leiden Univ., Leiden, The Netherlands), Prof. Christa Müller (Univ. of Bonn, Bonn, Germany), Prof. Ray A. Olsson (Univ. of South Florida), and John W. Daly, Susanna Tchilibon, Hayamitsu Adachi, and Bhalchandra V. Joshi (all NIDDK) for helpful discussions and supplying compounds.

Abbreviations

- ADA

adenosine deaminase

- CHAPS

3-[(3-cholamidopropyl) dimethylammonio] propanesulfonate

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- Cl-IB-MECA

1-[2-chloro-6[[(3-iodophenyl)methyl]amino]-9H-purin-9-yl]-1-deoxy-N-methyl-β-D-ribofuranuronamide

- CCPA

2-chloro-N6-cyclopentyladenosine

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- CPA

N6-cyclopentyladenosine

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium

- DMSO

dimethylsulfoxide

- ERK

extracellular receptor-activated kinase

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- GRK

G protein-coupled receptor kinase

- HEPES

N-(2-hydroxyethyl)-piperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid

- LJ1251

(2R,3R,4S)-2-(2-chloro-6-(3-iodobenzylamino)-9H-purin-9-yl)tetrahydrothiophene-3,4-diol

- IB-MECA

1-[6-[[(3-iodophenyl)methyl]amino]-9H-purin-9-yl]-1-deoxy-N-methyl-β-D-ribofuranuronamide

- LUF6000

N-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-2-cyclohexyl-1H-imidazo[4,5-c]quinolin-4-amine

- MRS541

N6-(3-iodobenzyl)-adenosine

- MRS542

2-chloro-N6-(3-iodobenzyl)-adenosine

- MRS1523

3-propyl-6-ethyl-5-[(ethylthio)carbonyl]-2-phenyl-4-propyl-3-pyridine carboxylate

- MRS 1220

N-[9-chloro-2-(2-furanyl)[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-c]quinazolin-5-yl]benzeneacetamide

- MRS3558

(1′R,2′R,3′S,4′R,5′S)-4-{2-chloro-6-[(3-chlorophenylmethyl)amino]purin-9-yl}-1-(methylaminocarbonyl)bicyclo[3.1.0]hexane-2,3-diol

- CGS21680

2-[p-(2-carboxyethyl)phenyl-ethylamino]-5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine

- NECA

adenosine-5β-N-ethyluronamide

- PTX

pertussis toxin

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.DeWire SM, Ahn S, Lefkowitz RJ, Shenoy SK. Beta-arrestins and cell signaling. Annu Rev Physiol. 2007;69:483–510. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.022405.154749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shenoy SK, Barak LS, Xiao K, Ahn S, Berthouze M, Shukla AK, Luttrell LM, Lefkowitz RJ. Ubiquitination of beta -arrestin links 7-transmembrane receptor endocytosis and ERK activation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29549–29562. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700852200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gurevich VV, Gurevich EV. The structural basis of arrestin-mediated regulation of G-protein-coupled receptors. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;110:465–502. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobson KA, Gao ZG. Adenosine receptors as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:247–264. doi: 10.1038/nrd1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Madi L, Cohen S, Ochayin A, Bar-Yehuda S, Barer F, Fishman P. Overexpression of A3 adenosine receptor in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in rheumatoid arthritis: involvement of nuclear factor-kappaB in mediating receptor level. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:20–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Madi L, Ochaion A, Rath-Wolfson L, Bar-Yehuda S, Erlanger A, Ohana G, Harish A, Merimski O, Barer F, Fishman P. The A3 adenosine receptor is highly expressed in tumor versus normal cells: potential target for tumor growth inhibition. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:4472–4479. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen GJ, Harvey BK, Shen H, Chou J, Victor A, Wang Y. Activation of adenosine A3 receptors reduces ischemic brain injury in rodents. J Neurosci Res. 2006;84:1848–1855. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang H, Avila MY, Peterson-Yantorno K, Coca-Prados M, Stone RA, Jacobson KA, Civan MM. The cross-species A3 adenosine-receptor antagonist MRS 1292 inhibits adenosine-triggered human nonpigmented ciliary epithelial cell fluid release and reduces mouse intraocular pressure. Current Eye Res. 2005;30:747–754. doi: 10.1080/02713680590953147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao ZG, Kim SK, Biadatti T, Chen W, Lee K, Barak D, Kim SG, Johnson CR, Jacobson KA. Structural determinants of A3 adenosine receptor activation: Nucleoside ligands at the agonist/antagonist boundary. J Med Chem. 2002;45:4471–4484. doi: 10.1021/jm020211+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferguson G, Watterson KR, Palmer TM. Subtype-specific kinetics of inhibitory adenosine receptor internalization are determined by sensitivity to phosphorylation by G protein-coupled receptor kinases. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;57:546–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trincavelli ML, Tuscano D, Marroni M, Falleni A, Gremigni V, Ceruti S, Abbracchio MP, Jacobson KA, Cattabeni F, Martini C. A3 adenosine receptors in human astrocytoma cells: agonist-mediated desensitization, internalization, and down-regulation. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:1373–1384. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.6.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bar-Yehuda S, Silverman MH, Kerns WD, Ochaion A, Cohen S, Fishman P. The anti-inflammatory effect of A3 adenosine receptor agonists: a novel targeted therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Expert Opin Invest Drugs. 2007;16:1601–1613. doi: 10.1517/13543784.16.10.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santini F, Penn RB, Gagnon AW, Benovic JL, Keen JH. Selective recruitment of arrestin-3 to clathrin coated pits upon stimulation of G protein-coupled receptors. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:2463–2470. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.13.2463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yan YX, Boldt-Houle DM, Tillotson BP, Gee MA, D’Eon BJ, Chang XJ, Olesen CE, Palmer MA. Cell-based high-throughput screening assay system for monitoring G protein-coupled receptor activation using beta-galactosidase enzyme complementation technology. J Biomol Screen. 2002;7:451–459. doi: 10.1177/108705702237677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olson KR, Eglen RM. Beta galactosidase complementation: a cell-based luminescent assay platform for drug discovery. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2007;5:137–144. doi: 10.1089/adt.2006.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim SK, Jacobson KA. Three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship of nucleosides acting at the A3 adenosine receptor: Analysis of binding and relative efficacy. J Chem Inf Model. 2007;47:1225–1233. doi: 10.1021/ci600501z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Göblyös A, Gao ZG, Brussee J, Connestari R, Neves Santiago S, Ye K, IJzerman AP, Jacobson KA. Structure activity relationships of 1H-imidazo[4,5-c]quinolin-4-amine derivatives new as allosteric enhancers of the A3 adenosine receptor. J Med Chem. 2006;49:3354–3361. doi: 10.1021/jm060086s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cosyn L, Palaniappan KK, Kim SK, Duong HT, Gao ZG, Jacobson KA, Van Calenbergh S. 2-Triazole-substituted adenosines: A new class of selective A3 adenosine receptor agonists, partial agonists, and antagonists. J Med Chem. 2006;49:7373–7383. doi: 10.1021/jm0608208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tchilibon S, Joshi BV, Kim SK, Duong HT, Gao ZG, Jacobson KA. (N)-Methanocarba 2,N6-disubstituted adenine nucleosides as highly potent and selective A3 adenosine receptor agonists. J Med Chem. 2005;48:1745–1758. doi: 10.1021/jm049580r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park KS, Hoffmann C, Kim HO, Padgett WL, Daly JW, Brambilla R, Motta C, Abbracchio MP, Jacobson KA. Activation and desensitization of rat A3-adenosine receptors by selective adenosine derivatives and xanthine-7-ribosides. Drug Devel Res. 1998;44:97–105. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2299(199806/07)44:2/3<97::AID-DDR7>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trincavelli ML, Tuscano D, Cecchetti P, Falleni A, Benzi L, Klotz KN, Gremigni V, Cattabeni F, Lucacchini A, Martini C. Agonist-induced internalization and recycling of the human A3 adenosine receptors: role in receptor desensitization and resensitization. J Neurochem. 2000;75:1493–1501. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salvatore CA, Jacobson MA, Taylor HE, Linden J, Johnson RG. Molecular cloning and characterization of the human A3 adenosine receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:10365–10369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nordstedt C, Fredholm BB. A modification of a protein-binding method for rapid quantification of cAMP in cell-culture supernatants and body fluid. Anal Biochem. 1990;189:231–234. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(90)90113-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arunlakshana O, Schild HO. Some quantitative uses of drug antagonists. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1959;14:48–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1959.tb00928.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klotz K-N, Hessling J, Hegler J, Owman C, Kull B, Fredholm BB, Lohse MJ. Comparative pharmacology of human adenosine receptor subtypes -characterization of stably transfected receptors in CHO cells. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol. 1998;357:1–9. doi: 10.1007/pl00005131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beukers MW, Chang LC, von Frijtag Drabbe Künzel JK, Mulder-Krieger T, Spanjersberg RF, Brussee J, IJzerman AP. New, non-adenosine, high-potency agonists for the human adenosine A2B receptor with an improved selectivity profile compared to the reference agonist N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine. J Med Chem. 2004;47:3707–3709. doi: 10.1021/jm049947s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosethorne EM, Juliet R, Leighton-Davies JR, Beer D, Charlton SJ. ATP priming of macrophage-derived chemokine responses in CHO cells expressing the CCR4 receptor. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol. 2004;370:64–70. doi: 10.1007/s00210-004-0932-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gao ZG, Blaustein J, Gross AS, Melman N, Jacobson KA. N6-Substituted adenosine derivatives: Selectivity, efficacy, and species differences at A3 adenosine receptors. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;65:1675–1684. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00153-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao ZG, Mamedova L, Chen P, Jacobson KA. 2-Substituted adenosine derivatives: Affinity and efficacy at four subtypes of human adenosine receptors. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;8:1985–1993. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jeong LS, Choe SA, Gunaga P, Kim HO, Lee HW, Lee SK, Tosh D, Patel A, Palaniappan KK, Gao ZG, Jacobson KA, Moon HR. Discovery of a new nucleoside template for human A3 adenosine receptor ligands: D-4′-thioadenosine derivatives without 4′-hydroxymethyl group as highly potent and selective antagonists. J Med Chem. 2007;50:3159–3162. doi: 10.1021/jm070259t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao ZG, Joshi BV, Klutz A, Kim SK, Lee HW, Kim HO, Jeong LS, Jacobson KA. Conversion of A3 adenosine receptor agonists into selective antagonists by modification of the 5′-ribofuran-uronamide moiety. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16:596–601. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.10.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Rompaey P, Jacobson KA, Gross AS, Gao ZG, Van Calenbergh S. Exploring human adenosine A3 receptor complementarity and activity for adenosine analogues modified in the ribose and purine moiety. Bioorg Med Chem. 2005;13:973–983. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.11.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klaasse EA, IJzerman AP, de Grip WJ, Beukers MW. Internalization and desensitization of adenosine receptors. Purinergic Signalling. doi: 10.1007/s11302-007-9086-7. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shenoy SK, Lefkowitz RJ. Angiotensin II-stimulated signaling through G proteins and beta-arrestin. Sci STKE 2005. 2005 Nov 22;:311. doi: 10.1126/stke.3112005cm14. cm14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamano K, Mori K, Nakano R, Kusunoki M, Inoue M, Satoh M. Identification of the functional expression of adenosine A3 receptor in pancreas using transgenic mice expressing jellyfish apoaequorin. Transgenic Res. 2007;16:429–435. doi: 10.1007/s11248-007-9084-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matot I, Weininger CF, Zeira E, Galun E, Joshi BV, Jacobson KA. A3 Adenosine receptors and mitogen activated protein kinases in lung injury following in-vivo reperfusion. Critical Care. 2006;10:R65. doi: 10.1186/cc4893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kenakin T. New concepts in drug discovery: collateral efficacy and permissive antagonism. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:919–927. doi: 10.1038/nrd1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Violin JD, Lefkowitz RJ. beta-Arrestin-biased ligands at seven-transmembrane receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:416–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shenoy SK, Drake MT, Nelson CD, Houtz DA, Xiao K, Madabushi S, Reiter E, Premont RT, Lichtarge O, Lefkowitz RJ. beta-arrestin-dependent, G protein-independent ERK1/2 activation by the beta2 adrenergic receptor. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:1261–1273. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506576200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fredholm BB, Irenius E, Kull B, Schulte G. Comparison of the potency of adenosine as an agonist at human adenosine receptors expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2001;61:443–448. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00570-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gao ZG, Duong HT, Sonina T, Kim SK, Van Rompaey P, Van Calenbergh S, Mamedova L, Kim HO, Kim MJ, Kim AY, Liang BT, Jeong LS, Jacobson KA. Orthogonal activation of the reengineered A3 adenosine receptor (neoceptor) using tailored nucleoside agonists. J Med Chem. 2006;49:2689–2702. doi: 10.1021/jm050968b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]