Abstract

The rate-limiting step of transcriptional activation in eukaryotes, and thus the critical point for gene regulation, is unknown. Using the inducible PHO5 gene of yeast as a model, we show that essential features of the transcriptional activation process can be described by a small number of simple assumptions about the chemical nature of the process. Our analysis elucidates the functional link between the dynamics of chromatin structure and gene regulation. It suggests a model for the underlying mechanism of promoter chromatin remodeling, which stochastically removes nucleosomes but appears to conserve a single nucleosome at all times when the promoter is bounded with respect to nucleosome sliding. All current experimental data are consistent with the hypothesis that promoter nucleosome disassembly is rate limiting for PHO5 expression.

Introduction

The nucleosome serves as a general transcriptional repressor in eukaryotes; its repression is relieved by “chromatin remodeling”, which exposes promoter DNA for interaction with the transcription machinery (Workman and Kingston, 1998). The PHO5 promoter of yeast has served as an important model to address the relation between chromatin structure and gene regulation. Early work, based on nuclease digestion, suggested the complete removal of histones from the transcriptionally active PHO5 promoter (Almer et al., 1986). Later it was found by chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis (ChIP) that histones are still present at transcriptionally active promoters but in a posttranslationally modified state. The exposure of promoter DNA was reconciled with the retention of histones by the hypothesis of an altered nucleosome, whose modified structure would be conducive to transcription (Paranjape et al., 1994). Biochemical analysis of chromatin remodeling complexes lent support to this hypothesis (Cote et al., 1998; Schnitzler et al., 1998). Upon reexamination of the PHO5 promoter by a number of quantitative methods, we have come to a different conclusion: histones are neither completely removed nor fully retained on the activated promoter, and those that are retained are in the form of unaltered nucleosomes, indistinguishable from nucleosomes in the repressed state (Boeger et al., 2003; Boeger et al., 2004).

The repressed PHO5 promoter contains nucleosomes in defined locations. Nucleosomes N-1 and N-2 encompass the TATA box and upstream activation sequence UASp2, respectively. A second regulatory sequence, UASp1, is exposed in the linker between nucleosomes N-2 and N-3 (Almer et al., 1986). Activation of the PHO signaling pathway leads to dephosphorylation of the transcriptional activator Pho4p, which, in its dephosphorylated form, enters the nucleus and binds at both upstream activator sequences (Kaffman et al., 1994; Kaffman et al., 1998; Venter et al., 1994). The subsequent remodeling of chromatin structure as well as transcriptional activation depend on Pho4p and both upstream activation sequences (Svaren and Horz, 1997).

Our previous quantitative measurements, by topology and limit nuclease digestion analyses, revealed an average of 1.1 nucleosomes remaining in the transcriptionally activated state (Boeger et al., 2003). These nucleosomes are apparently unaltered in structure and are distributed among the three original locations, with 0.6 occupying the transcription start site (N-1) and about 0.2 and 0.3 occupying the locations N-2 and N-3, respectively (Boeger et al., 2003). The fractional occupancies contrast with the presumed capacity of all cells to remove nucleosomes from all three promoter positions. The contradiction is resolved by the proposal that promoter nucleosomes are continually removed and reformed in the activated state (Boeger et al., 2003). Thus, activation may be viewed as a transformation of promoter chromatin from a static to a dynamic state. On this basis, a population of activated promoters will be heterogeneous, and may best be described in statistical terms. The same conclusion has been reached by single cell expression analysis of promoter function (Raser and O’Shea, 2004), and by accessibility analysis of single promoter templates in vivo (Jessen et al., 2006).

The retention of 1.1 nucleosomes in the stationary activated state may be attributed entirely to a dynamic equilibrium of nucleosome disassembly and reassembly (“dynamic retention”). Alternatively, the remodeling mechanism may conserve one promoter nucleosome at all times (“stable retention”), which is slid between different nucleosome positions, but never removed from the promoter. The possibility of stable nucleosome retention is suggested by recent biochemical and structural studies of the RSC chromatin remodeling complex. RSC was seen to partially envelop a nucleosome, binding the histones and contacting the DNA through its Sth1p subunit near the dyad axis of the nucleosome (Chaban et al., submitted). Sth1p was shown to serve as an ATP-dependent translocase, drawing DNA into the nucleosome from the linker region on one side and ejecting it on the other thus sliding the nucleosome along the DNA (Saha et al., 2002; Saha et al., 2005). In the process, DNA becomes accessible to restriction enzymes only in the linker region, and not, as widely assumed, on the surface of the histone octamer (Saha et al., 2005). Thus RSC and its close relative SWI/SNF expose the DNA of mononucleosomes, most likely due only to their ability to slide the histone octamer off the end of the DNA by about 50 base pairs (Flaus and Owen-Hughes, 2003; Kassabov et al., 2003; Saha et al., 2005), as previously suggested (Jaskelioff et al., 2000).

In the chromatin fiber, translocation of the nucleosome may continue past the end of the linker, unspooling the DNA from the neighboring nucleosome (Cairns, 2007). We will refer to this mechanism as “sliding-mediated nucleosome disassembly” (Fig. 1A). Such unspooling was previously shown to occur during passage through a nucleosome by processive enzymes, such as nucleases and polymerases (Lorch et al., 1987; Prunell and Kornberg, 1978). The ability to slide a nucleosome partially off the end of the DNA indicates that RSC slides nucleosomes without the requirement for making contact with the linker DNA ahead of the nucleosome. The same ability may enable the RSC-nucleosome complex to invade a neighboring nucleosome during sliding. The chromatin remodeling machine thus utilizes the nucleosome it binds, to remove another nucleosome. All promoter nucleosomes susceptible to disassembly may be removed, except for the one bound to the remodeling complex.

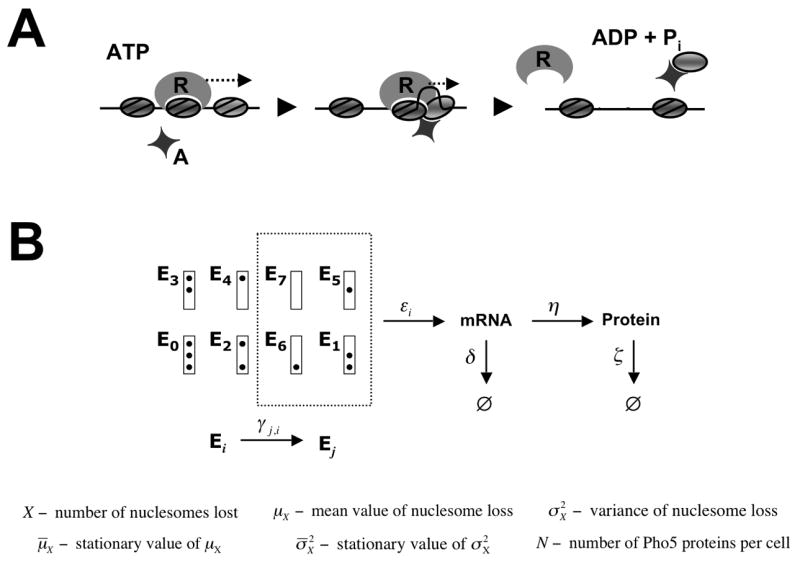

Figure 1.

(A) Sliding mediated nucleosome disassembly. Not the nucleosome bound by the remodeler R, but an adjacent nucleosome is disassembled as a consequence of nucleosome sliding catalyzed by R. Histone acceptors, A, may be required for complete unwrapping of the DNA from the histone octamer. Nucleosomes are represented by grey ovals. (B) Promoter nucleosome configurations E 0, …,E 7. The box represents the promoter, and dots indicate occupied nucleosome positions, with nucleosome positions N-1 (the core promoter), N-2, and N-3 at the top, middle, and bottom, respectively. Under repressing conditions the promoter is found in nucleosome configuration E 0 with probability 1, but randomly jumps between configurations Ei under activating conditions. Only configurations Ei that lack a nucleosome in position N-1, i.e. i ∊ {1,5,6,7}, are transcriptionally competent.

Here we present a model for the transcriptional activation of PHO5. The model demonstrates that the retention of promoter nucleosome in the activated state affords a key to understanding the mechanism and regulatory significance of promoter chromatin remodeling. Our analysis bears out the expectation of a random process of nucleosome disassembly and reassembly that gradually tends towards equilibrium. It suggests that that removal of promoter nucleosomes is rate-limiting for PHO5 expression, and that nucleosomes are retained at the induced promoter by to two distinct mechanisms, illuminating the underlying mechanism of chromatin remodeling.

Results

We describe the transcriptional activation of PHO5 as a random process, extending previous work of others (Peccoud and Ycart, 1995; Raser and O’Shea, 2004). The abstract notion of switching between a transcriptionally competent and a non-competent state (Peccoud and Ycart, 1995) is replaced by a model for the promoter chromatin transition, which reflects our current understanding of chromatin remodeling at PHO5. We specify the activation process by making the following

Premises and Definitions

Premise 1

The promoter assumes either one of the eight nucleosome configurations E0, …,E7 defined in Figure 1B.

The cellular state with respect to PHO5 expression is represented by a triple x = (i,m,n), where i refers to the nucleosome configuration Ei, and m and n refer to the number of PHO5 mRNA and protein molecules, respectively.

For our analysis two random variables will be of interest: X, the number of nucleosomes lost, with mean value μX and variance , and N, the number of Pho5 proteins, with mean value μN, and variance (Figure 1). We designate stationary values of these functions, reached at the end of the activation process (Methods), as μ̄X, , μ̄N, and , respectively (Figure 1).

Premise 2

The activation process evolves according to a time-homogenous Markov chain. Thus, the probability P(xj, t + h| xi, t) of finding the cell in state xj at time t + h, given that the cell was in state xi at time t, is given by

| (1) |

for all h small enough such that the occurrence of more than one transition xi → xj between t and t + h is of negligible probability.

It can be shown that the inverse of the ‘propensity function’ ξj,i for the transition xi → xj (Gillespie, 2007) gives the average time that the cell dwells in state xi before the transition (which is presumed to be rapid). For simplicity, we will refer to ξj,i as the ‘rate’ of reaction xi → xj.

The activation process encompasses the following reactions: Transitions from nucleosome configuration Ei into configuration Ej, which occur with rate γj,i , where γj,i is a constant; transitions from (i, m, n)-states into (i, m − n) -states, and into (i,m + 1,n)-states, which occur with rates mδ and εi, respectively, where δ, εi are constants ; and transitions from (i,m,n)-states into (i,m,n − 1)-states, and into (i,m,n + 1)-states, which occur with rates nζ and mη, respectively, where ζ, η are constants .

Equation (1) implies that the transition probability only depends on the current state xi and the final state xj and is the same for all time intervals h of equal length. - The transition probability does not depend, therefore, on time itself or the sequence of transitions leading up to xi. A time-homogenous Markov chain is thus endowed with complete lack of memory. It can be proved that a process specified by (1) is the only process with this property (Feller, 1957).

Premise 3

Nucleosome disassembly reactions are reversible under activating conditions.

Premise 3 is a consequence of experimental measurements suggesting that μ̄X is non-integral (Boeger et al., 2003), and that mutations in the Pho4p activation domain appear to gradually shift μ̄X toward smaller values (McAndrew et al., 1998). If premise 3 were incorrect, μ̄X could assume only two values, 0 or an integer > 0.

Premise 4

Removal of the core promoter nucleosome N-1 is required for transcriptional activation. Thus, εi = 0 for i = 0, 2, 3, 4, where i refers to the nucleosome configuration Ei (Fig. 1).

Consistent with Premise 4, nucleosomes at the start site of transcription inhibit the initiation of transcription in vitro (Lorch et al., 1987), and transcriptional activation coincides with the removal of the core promoter nucleosome N-1 at PHO5 in vivo (Boeger et al., 2003; Reinke and Horz, 2003).

Dynamic and stable nucleosome retention

We begin our analysis by examining the effect of dynamic and stable nucleosome retention (E7 disallowed) on the structural heterogeneity of promoter populations. The time-evolution of the chromatin transition is given by a finite system of coupled ordinary differential equations derived from (1) and the laws of probability (Methods, equation (7)). We calculated μX and from the solutions of these equations for stable and dynamic nucleosome retention, making the following simplifying assumptions that do not affect the conclusions of our analysis: First, all promoters are in configuration E0 at t = 0. Second, disassembly and reassembly reactions remove and add nucleosomes one-by-one. Third, all nucleosome disassembly reactions occur with equal rate γd, and all reassembly reactions occur with equal rate γr. The ratio γd/γr is chosen so that μ̄X = 1.9 (Boeger et al., 2003).

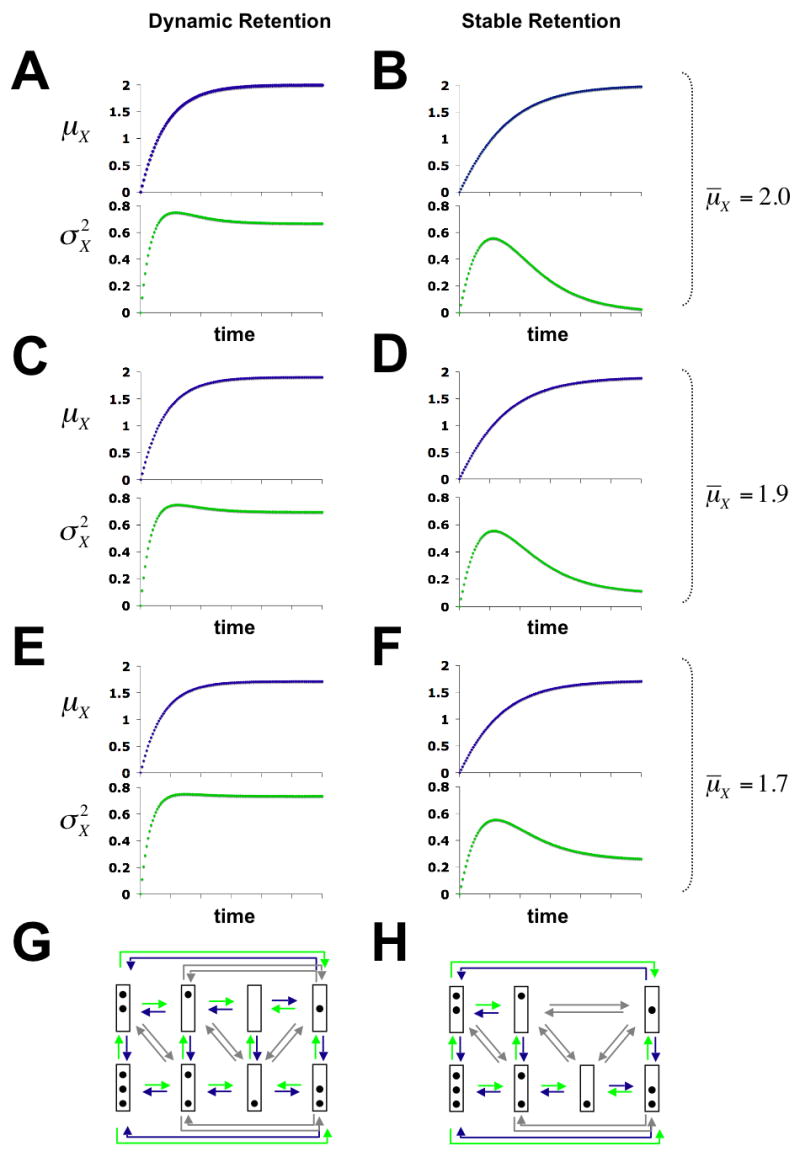

As expected for a random process of nucleosome disassembly and reassembly, promoter populations become heterogeneous in X upon induction (Figure 2). In the case of dynamic nucleosome retention (Figure 2G), is almost as high as the maximal value of attained early in the activation process (Figure 2C). In the case of stable nucleosome retention (Figure 2H), however, the promoter population becomes mostly, but not entirely, uniform in X at the end of the activation process (Figure 2D). The remaining heterogeneity in the stationary state results from the dynamic retention of 0.1 nucleosomes due to Premise 3. Only in the absence of nucleosome reassembly does the promoter population become entirely uniform (Figure 2B). The predicted variance profile for stable nucleosome retention approaches the profile for dynamic retention as μ̄X approaches 0. However, the two models predict distinct variance profiles over a range of values for μ̄X ≤ 2 (Figure 2). (For μ̄X > 2, the stable retention model is invalid. Only for μ̄X close to 3, and thus for values much larger than the observed value of 1.9, does the variance profile for dynamic retention resemble the variance profile for stable retention at μ̄X = 1.9). The models imply different values for the ratio γd/γr (Figure 2, legend), which determines the stability of the stationary distribution of X with respect to perturbations in γd and γr, and which is therefore a critical parameter of the chain.

Figure 2.

Predicted time-evolution of μX, the mean number of nucleosome loss (blue graphs), and , the variance of nucleosome loss (green graphs) for dynamic (A, C, E, G), and stable (B, D, F, H) retention of nucleosomes at different values of μ̄X. Panels at the bottom show the chromatin transition topologies for both models of nucleosome retention. Nucleosome disassembly, reassembly and sliding transitions are indicated by green, blue, and grey arrows, respectively. Time-evolutions were calculated from solutions to the system of differential equations (7) (Methods). For A, C, …, E the ratios γd/γr are 2, 10, 1.74, 3.17, and 1.33, respectively. For B the ratio is not defined, since γr = 0.

Measuring the heterogeneity of promoter chromatin structure

Distinguishing between the models of dynamic and stable nucleosome retention requires measuring the heterogeneity in X for different promoter populations of the activation process. Such measurements have not been attempted previously. We therefore propose an experimental approach to address this problem and demonstrate its feasibility.

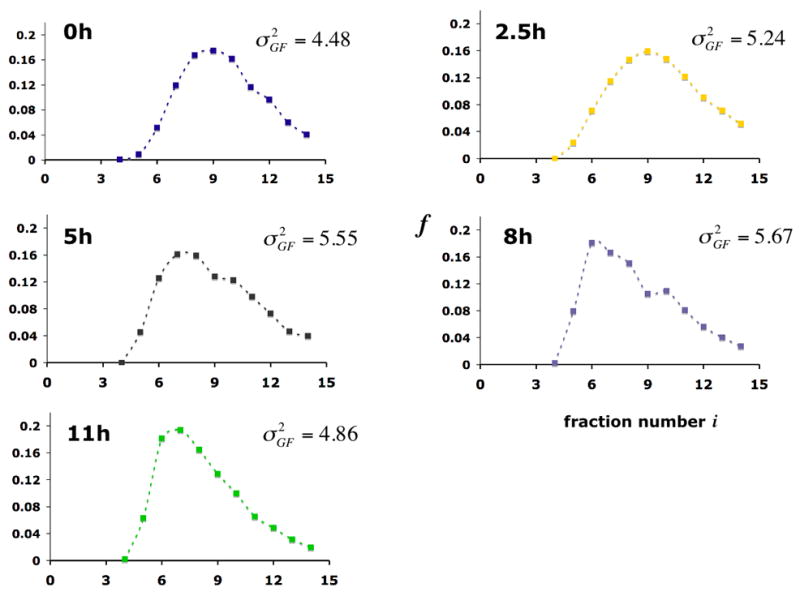

To investigate PHO5 promoter chromatin heterogeneity and the approach to equilibrium, we employed a yeast strain whose PHO5 promoter was flanked by the recognition element of the site-specific R recombinase, and that expresses R under control of the inducible GAL1 promoter. We formed promoter chromatin circles bearing three nucleosomes in cells grown under repressing conditions by activating the GAL1 promoter, and then induced PHO5 expression by transfer of the cells into phosphate-free medium (Boeger et al., 2004). Circles were extracted at various times and fractionated by gel filtration, according to the number of nucleosomes they carry. The center of the gel filtration profile shifted towards earlier eluting fractions, over the course of PHO5 activation (Fig. 3), as expected because circles with the fewest nucleosomes and so, presumably, the largest contour length, should be the first to elute from the column (Griesenbeck et al., 2003). The gel filtration profile was narrowest before induction, indicating that the initial circle population was the most uniform. The profile increased in width early in the course of activation and then became narrower towards the end, as shown by calculation of the variance of the profile, (Fig. 3). The changes in suggest a changing heterogeneity in the number of circle nucleosomes over the course of PHO5 activation.

Figure 3.

Gel filtration profiles of promoter chromatin circles at various times after induction of PHO5 expression. Promoter circles were fractionated on a Sephadex TSK 4000 SW column, and the fraction fi of all circles in column fraction i was determined by southern blotting with a radioactively labeled circle DNA probe. The variance of the gel filtration profile , where (mass center of the profile), is indicated at the right.

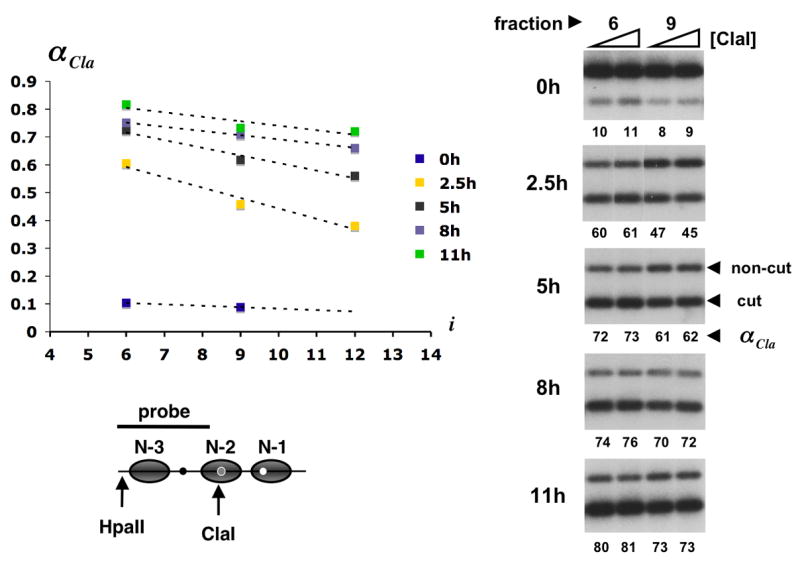

Actual nucleosome loss from the circles was assessed by an increase in accessibility to digestion by restriction endonuclease Cla I, which cuts near the center of nucleosome N-2 (Fig. 4). Cla I accessibility was measured for three fractions from each gel filtration profile and the gradient of accessibility over the entire profile was then determined by linear regression. Accessibility to Cla I (αCla) was uniformly low (near zero slope, aGF, of the accessibility plot in Fig. 4) at time 0, before activation, as expected for a uniform population of circles, all bearing three promoter nucleosomes. At intermediate times, there was a gradient (steep slope, large negative value of aGF) from higher accessibility in early eluting fractions to lower accessibility in later fractions, indicative of circles with fewer nucleosomes in earlier fractions and more nucleosomes in later fractions (Griesenbeck et al., 2003). At late times, the Cla I accessibility was nearly uniform again (smaller, though still non-zero, value of aGF).

Figure 4.

Cla I accessibility across gel filtration profiles from Fig. 1. About 20 attomol of promoter circles from column fractions 6 and 9 (0 h after induction) or fractions 6, 9, and 12 (2.5, 5, 8, and 11 h after induction) were digested in 300 μl with 20 and 60 u of Cla I for 30 min at 37°C. Circle DNA was extracted, digested to completion with Hpa II, separated in a 2% agarose gel, blotted and hybridized with the radioactively labeled DNA probe indicated in the promoter diagram at the bottom of the figure (gray ovals represent nucleosome core particles; black, grey, and white dots represent UASp1, UASp2, and the TATA box, respectively). Primary data for fractions 6 and 9 are shown on the right. The lower and upper bands represent circles cut and not cut by Cla I. The fraction of circles cut, αCla, is indicated as a percentage beneath each lane. The mean of αCla at 20 and 60 u of Cla I was plotted against the column fraction number i = 4,…,14 (upper left). Cla I accessibility gradients were determined by linear regression.

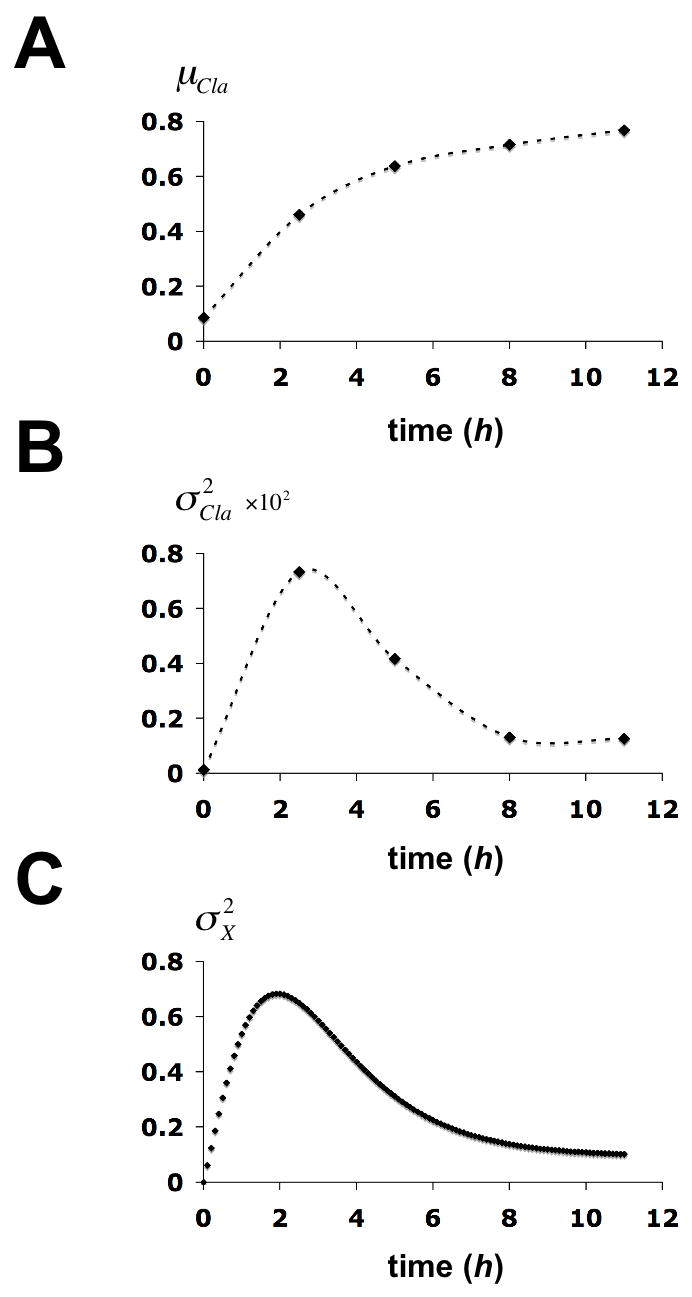

As a measure for the heterogeneity in X we calculated the variance, , of the accessibility for each gel filtration profile from the relation , where αi is the value from the accessibility plot of αCla for the ith column fraction, fi is the fraction of all circles in the entire gel filtration profile in the ith column fraction, and is the mean value of accessibility. The variance of Cla I accessibility is related to aGF and through the relation . The time-evolution of μα (Fig. 5A) shows a monotonic rise and asymptotic approach to a limiting value of approximately 0.8, as expected from our previous evidence for about 0.2 nucleosomes remaining at N-2 in the fully active state (Boeger et al., 2003). The time-evolution of (Fig. 5B), is noteworthy in three respects. First, the marked rise in at intermediate times indicates the development of a heterogeneous circle population, as expected for a random process of nucleosome removal. Second, the remodeling process approaches a stable limit as PHO5 activity reaches a maximum after about 8 hours of induction (Barbaric et al., 2003). Third, the time-evolution of heterogeneity in X conforms with the expectation of stable rather than dynamic nucleosome retention. The structure of promoter chromatin in the stationary activated state is therefore heterogeneous in one respect but uniform in another: nucleosomes are distributed in a statistical manner among the locations N-1, N-2, and N-3, but every promoter possesses almost exactly one nucleosome. The alternative that active promoters contain varying numbers of nucleosomes, ranging from zero to three, with an average of one, as implied by the model of dynamic nucleosome retention, is excluded. Additional proof of this conclusion will have to await further progress in the isolation of defined chromatin domains for their analysis by electron microscopy (Griesenbeck et al., 2004).

Figure 5.

Time evolution of statistical parameters for the chromatin structure transition at the PHO5 promoter. (A) The mean of Cla I accessibility of the gel filtration profile at time t after induction, μα(t), is plotted against the time. (B) The variance of Cla I accessibility of the gel filtration profile at time t, , is plotted against the time. (C) The variance in X at time t, , was calculated from the solution to equation (7) (Methods) and plotted against time. Calculations were based on the chromatin transition topology of Fig. 2B with γj, 0 = 0.2 h−1 for j ∈ {1,2,3}, γj, i = 2 · γj,0 for all (j, i) with i ∈ {1,2,3} and j ∈ {4,5,6},γ0,i = 0.1 · γj,0 for i ∈ {1,2,3},γj,i = 0.2 · γj,0 for all (j, i) with i ∈{4,5,6} and j ∈{1,2,3}, and γj,i = 2 · γj,0 for all sliding transitions.

Fitting the time-evolution of to the observed time-evolution of heterogeneity in X allowed us to derive an estimate for γd. The rate for nucleosome reassembly is then determined by the stationary mean value of nucleosome loss μ̄X = 1.9. The fit can be further improved by assuming that removal of the first nucleosome stimulates removal of the second nucleosome (Fig. 5C), which might be because an additional activator binding site, UASp2, becomes available for activator binding upon removal of nucleosome N-2 (Figure 4), and because of the processivity of the disassembly mechanism. We note that γd < 1h−1. The half life of the PHO5 transcript, t0.5, is about 5 min (Vogelauer et al., 2000). Assuming a steady state level of 12 mRNA molecules per cell in a transcriptionally competent promoter state, the rate of transcription is given by ε = (ln(2)/t0.5) · 12 = 100 h−1, thus γd ≪ ε. This conclusion suggests that nucleosome disassembly is rate-limiting for PHO5 expression.

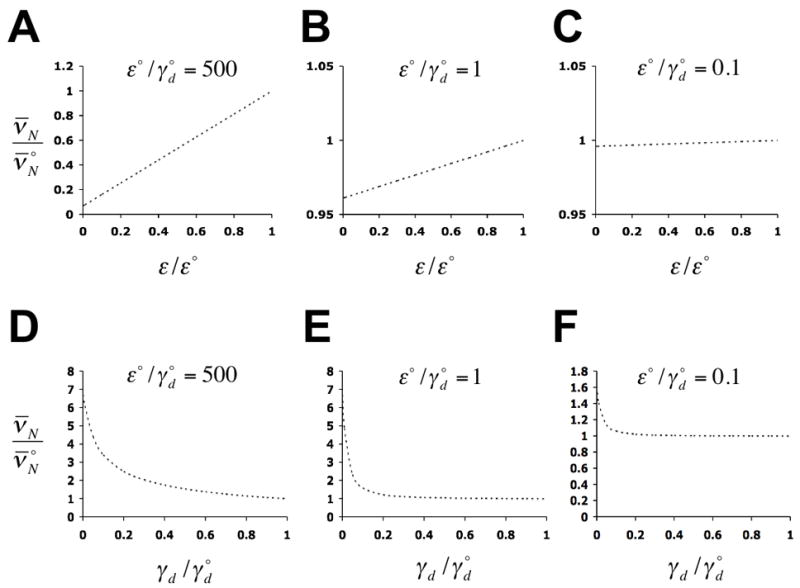

The noise of expression and the rate-limiting step of transcriptional activation

The PHO signaling pathway, which regulates PHO5 expression, must affect the rate-limiting transition of the activation process. We therefore calculated the effect of decreasing rates γd and εi on the stationary (intrinsic) noise strength of expression, , which has previously been measured at different activity levels of the PHO signaling pathway. The stationary noise strength was seen to increase about four fold with decreasing PHO signaling activity (Raser and O’Shea, 2004). For simplicity, we assumed that εi = ε for i = 1, 5, 6. Figure 6 shows that ν̄N increases with decreasing γd, but not with decreasing ε. This suggests that the PHO signaling pathway regulates the rate of nucleosome disassembly rather than the rate of transcription and, therefore, that nucleosome disassembly is rate-limiting for PHO5 expression (γd ≪ ε), consistent with the analysis of the chromatin transition. The noise strength profile of Figure 6D, which closely resembles the experimental results (Raser and O’Shea, 2004), is a function of the random switching of the promoter between transcriptionally competent and non-competent states, and thus of the dynamics of nucleosome removal and reformation. This contrasts with previous suggestions of complete (irreversible) removal of promoter nucleosomes upon transcriptional activation of PHO5 (Almer et al., 1986; Reinke and Horz, 2003).

Figure 6.

Predicted dependence of the stationary intrinsic noise strength of expression, ν̄N, on the rate of transcription (A – C), and on the rate of nucleosome disassembly (D – F), with all other rate constants held constant. The maximum rates of transcription and nucleosome disassembly are designated as ε° and , respectively, where refers to ν̄N at ε = ε° and . Predictions were calculated from solutions to equations (15) (Methods), with δ = 10 h−1, ζ = 0.7 h−1, η = 20 h−1, ε° = 100 h−1, εi ≡ ε for i ∈ {1,5,6}, εi = 0 for i ∈{2,3,4}, and γj,0 ≡ γd for i ∈ {1,2,3}, all other γj,i are then given by the relations of Fig. 5C.

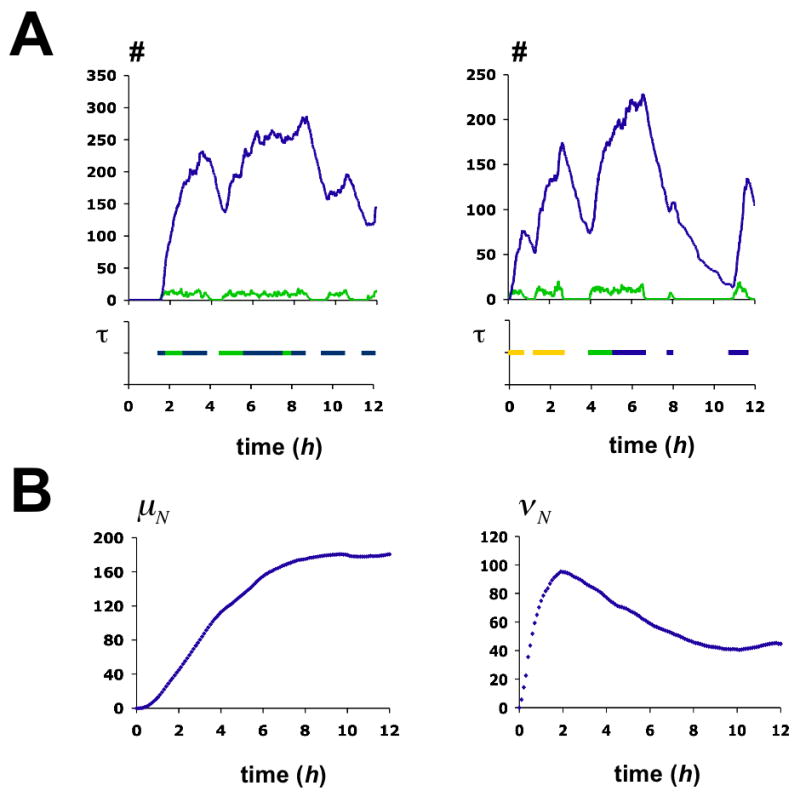

We used stochastic simulations to predict, on the basis of our model, the kinetics of Pho5p production, employing the rates of nucleosome disassembly and reassembly derived from our analysis of the promoter chromatin transition (Figure 7C). We note that the result closely agrees with previous experimental measurements (Barbaric et al., 2003). The kinetics of the chromatin transition determines the kinetics of gene expression.

Figure 7.

Stochastic simulation of the activation process. (A) Two examples of single simulation runs over 12 hours. Graphs in the upper panels show the time-evolution of protein (blue) and mRNA (green). The pertaining chromatin transitions are indicated in the panels below. The function τ equals 1 if the promoter is in either one of the three transcriptionally competent nucleosome configurations E1 (yellow), E 5 (blue), E 6 (green), and is 0 otherwise. Monte Carlo simulations were performed using Gillespie’s algorithm (Gillespie, 1976). (B) Time-evolution of the mean number of Pho5p molecules, μN, and the intrinsic noise strength of Pho5p expression, νN. Statistics were derived from 1000 simulations. Chromatin transition rates γj,i are given in the legend to Fig. 5C. All other rates are as indicated in the legend to Fig. 6.

Discussion

The gene expression model presented here links transcriptional behavior to the dynamics of promoter chromatin structure. The model is characterized by the following assumptions: The transcriptional activation process evolves as a time-homogenous Markov chain tending towards equilibrium. The slow chromatin transition reflects low transition probabilities between nucleosome configurations Ei (Fig. 1) rather than the slow unfolding of nucleosomes, consistent with the apparent lack of stable intermediates of the disassembly reaction (Boeger et al., 2003). Nucleosome disassembly is the rate-limiting step of the activation process. Therefore, histone modifications that play a critical gene regulatory role at PHO5 must ultimately control nucleosome stability (see below). Nucleosomes are retained by reassembly, and as a consequence of stable nucleosome retention, consistent with a mechanism of sliding-mediated nucleosome disassembly (Cairns, 2007).

We showed that the model correctly predicted experimentally testable properties of the process, such as the time-evolution of structural promoter heterogeneity, the intrinsic stationary noise strength of expression as a function of PHO signaling activity, and the kinetics of protein production. The behavior of the activation process is essentially recaptured by a small number of simple assumptions about the chemical nature of the process.

At least some of our assumptions are simplifying assumptions that can only be approximately correct. Thus, we assumed that the activation process is homogenous in time (Premise 2), which means that concentrations and activities of the factors that govern the process, like Pho4p and the remodeling factors it may recruit, remain constant. This does not take into account that Pho4p becomes fully active only after depletion of intracellular phosphate stores (Thomas and O’Shea, 2005). However, Pho4p is concentrated in the nucleus shortly after transfer of cells into phosphate-free medium (Thomas and O’Shea, 2005), and cells that lack the ability to store phosphate still require 8 hours or more in phosphate-free medium to fully express PHO5 (Thomas and O’Shea, 2005), suggesting that the kinetics of chromatin remodeling are mostly determined by rate constants pertaining to the remodeling process, rather than to the signaling pathway that precedes it.

It may be asked whether the structural heterogeneity observed at the chromatin level reflects the amplification of stochastic events due to positive or negative feedback at the level of the PHO signaling pathway (Wykoff et al., 2007). The different kinetics of PHO signaling and chromatin remodeling argue against this possibility; and the use of phosphate-free medium to induce nucleosome disassembly (see above), rendered the positive and negative feedback loops of the PHO signaling pathway inoperative due to the cell’s inability to import phosphate (Wykoff et al., 2007). Likewise, the uniformity in X reached at the end of the activation process cannot be attributed to properties of the signaling pathway either, since promoter circles isolated from pho80Δ cells that express PHO5 in the absence of PHO signaling are also uniform in X, as indicated by a near zero value for aGF (Griesenbeck et al., 2003). Nonetheless, an important test of the model presented here will be to measure the noise of expression and the variance of nucleosome loss in PHO4 mutants in the absence of PHO signaling.

Sliding-mediated nucleosome disassembly is supported by our findings due only to its heuristic qualities. The idea resolves the conundrum of how to mechanistically account for the stable retention of one promoter nucleosome while nucleosome removal occurs at all promoter positions. The proposed mechanism may be directly tested by single molecule analysis. Previous experiments using optical tweezers have addressed the effect of RSC activity on the length of chromatin templates at very low nucleosome densities to exclude nucleosome interactions (Zhang et al., 2006). Such interactions, however, would be likely at physiological nucleosome densities, and in this case sudden increases in the length of the stretched template are expected with every nucleosome that RSC removes from the template. By pulling at the DNA with forces strong enough to unwrap DNA from the histone octamer, the optical tweezer allows for counting the remaining nucleosomes at the end of the remodeling process. In the case of sliding-mediated nucleosome disassembly one nucleosome would always remain. RSC has been found to catalyze the removal of nucleosomes from linear DNA in the presence of the histone binding protein Nap1p (Lorch et al., 2006). As removal may have involved sliding of the nucleosome beyond the end of the DNA, the experiments should be repeated on circular DNA bearing one nucleosome only.

Since nucleosome sliding is a processive reaction, the notion of nucleosome disassembly by sliding raises in particular the question of how the cell limits the extent of remodeling processes. At the chromosomal PHO5 locus nucleosome removal is restricted to four promoter nucleosomes (including the three incorporated in the circles studied here, and a fourth, N-4, upstream of N-3) (Almer et al., 1986). Nucleosomes within the promoter region must somehow be rendered susceptible to disassembly, whereas nucleosomes at the boundaries of the promoter are not. Indeed, nucleosomes at promoters and DNase I ‘hypersensitive’ sites are generally enriched for acetylated histones and the histone variant H2A.Z (Birney et al., 2007; Kurdistani and Grunstein, 2003; Zhang et al., 2005), and genetic and biochemical evidence suggests a functional connection between histone marks and chromatin remodeling complexes (Chandy et al., 2006; Corona et al., 2002; Ferreira et al., 2007; Hassan et al., 2001; Pollard and Peterson, 1998). Certain histone marks and histone variants may poise nucleosomes for disassembly, or may be recognized by acceptor proteins that are required for complete unspooling of nucleosomal DNA and release of the histone octamer (Fig. 1A). A possible requirement for auxiliary factors in nucleosome disassembly is consistent with the observation that SWI/SNF alone is insufficient to remove nucleosomes from circular DNA molecules (Jaskelioff et al., 2000). Nucleosomes containing histone H2A.Z are less stable (Jin and Felsenfeld, 2007; Zhang et al., 2005), and it has been reported that the histone binding protein Asf1p is required for nucleosome removal from the PHO5 promoter (Adkins et al., 2004). Histones H3 and H4 associated with Asf1p are preferentially acetylated at some residues (Tyler et al., 1999), and histone acetylation appears to play a role in chromatin remodeling at the PHO5 promoter. The sequence-specific transcription factor Pho2p recruits the histone acetyltransferase Esa1p to the PHO5 promoter. Absence of Esa1p function causes loss of histone H4 acetylation marks from PHO5 promoter nucleosomes and results in PHO5 activation defects (Nourani et al., 2004). The histone acetyltransferase Gcn5p acetylates PHO5 promoter nucleosomes (Vogelauer et al., 2000), and in pho80Δ cells, in which PHO5 is constitutively expressed, the gene is inactive in the absence of Gcn5p (Gregory et al., 1998). The inactive promoter retains all its nucleosomes, but they are randomly positioned (Boeger et al., 2004; Gregory et al., 1998), which may be explained by the recruitment of a remodeling complex in the pho80Δ context and consequent sliding of nucleosomes, but a failure to release the histones for lack of acetylation.

Since sliding-mediated nucleosome disassembly is directional, nucleosomes at the boundaries of the remodeled region would only be removed in one direction, whereas those in the middle would be removed by sliding both ways, which would increase the level of nucleosomes at the boundaries relative to the middle. This may explain the symmetrical distribution of promoter nucleosomes in the stationary activated state, with higher levels of nucleosomes at the ends (positions N-1 and N-4) than in the middle (Almer et al., 1986). This discussion shows that conservation of one nucleosome at all times is not necessarily limited to the topologically closed promoter circle, but may equally apply to chromosomal domains. Indeed, promoter circles when formed from the activated chromosomal locus in the stationary state are again nearly uniform in X (Griesenbeck et al., 2003), suggesting that the chromosomal promoter, like the promoter circle, is closed with respect to nucleosome sliding.

Similar to PHO5, other promoters may randomly switch between a transcriptionally competent and non-competent states (Bar-Even et al., 2006), resulting in burst-like transcription (Raj et al., 2006). The molecular basis of this behavior, however, is unknown. The coexistence of nucleosomal and nucleosome-free states of the core promoter within a population of cells has been directly demonstrated for PHO5 (Boeger et al., 2003). It will have to be seen whether the statistical interpretation of chromatin remodeling enforced by the structural analysis of the PHO5 chromatin transition holds for other promoters, and whether the dynamics of nucleosome removal and reformation are slow in comparison with the rate of transcription. Dion et al. have estimated rates for histone exchange genome-wide based on a Markovian model. Although this model did not take into account the possibility of a nucleosome-free state, thus confounding rates of nucleosome disassembly and reassembly, and although the rates may have been affected by nonspecific association of histones with chromatin, due to overexpression of the histones in G1 (Rufiange et al., 2007), the analysis indicated that the average rate for exchange of histone H3 at promoters may be smaller than 1 h−1 (Dion et al., 2007). This suggests that the chromatin dynamics at other promoters, but not necessarily all of them, entail, similar to PHO5, the random and reversible disassembly of nucleosomes with rates much smaller than the expected rates of transcription. The frequent initiation of transcription at promoters stronger than PHO5 may entirely prevent the reformation of nucleosomes, either by sliding or reassembly. In this case, the noise of gene expression due to nucleosome dynamics eventually disappears.

Methods

Biochemical manipulations

Five liters of 2xSCR medium lacking leucine were inoculated with a preculture of yM3.2 cells (Boeger et al., 2004) transformed with the recombinase plasmid pB3.1 (Griesenbeck et al., 2003), and cultivated overnight at 30°C to a density of 4 · 107 cells/ml. Expression of R recombinase was induced by adding 500 ml of 20% D-galactose to the culture, followed by an additional 90 minutes of incubation at 30°C. Cells from 1 liter of culture were pelleted, washed with water and frozen in liquid nitrogen as previously described (Griesenbeck et al., 2004). The remaining cells were pelleted, washed in water, and resuspended in 12 liters of SCD medium lacking orthophosphate. Three liters of cells were removed after 2.5, 5, 8, and 11 hours of incubation at 30°C in a 13 l fermenter with regulated oxygen supply, washed in water and frozen in liquid nitrogen. The frozen cells were ground with dry ice in liquid nitrogen using a Warring blender (Griesenbeck et al., 2004). Ground cells were resuspended in 4 ml/g of buffer EX (25 mM HEPES·KOH pH7.4, 200 mM potassium acetate, 2 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 0.125 mM spermidine, 0.05 mM spermine, 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 330 mg/l benzamidine. 170 mg/l phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1.37 mg/l pepstatin A, 0.284 mg/l leupeptin) and centrifuged for 1h at 4 °C in a Ti45 rotor at 25,000 rpm. The supernatant was centrifuged for 3 h at 4°C in a Ti70 rotor at 60,000 rpm. Pellets were rinsed three times with 1 ml of EX buffer, and resuspended in RSP buffer (as buffer EX, however containing 100 mM potassium acetate, and 1 mM EDTA) to one tenth of the original volume. Of this resuspension, 500 μl were fractionated by gel filtration on a TSK4000SW column (TosoH Bioscience), which was equilibrated, prior to the fractionation, with buffer GF (25 mM HEPES·KOH pH7.1, 100 mM potassium acetate, 2 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, 0.125 mM spermidine, 0.05 mM spermine, 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol). We collected 500 μl fractions at a flow rate of 0.4 ml/min using buffer GF. Circle DNA was extracted from 100 μl of each fraction, digested with NcoI, and 0.66 volumes of the digested DNA were used for agarose gel electrophoresis. After electrophoresis, the DNA was blotted onto a nylon membrane and hybridized with a promoter-specific 32P-labeled DNA probe. For accessibility assays, we digested 20 attomol of chromatin circle in 150 μl of buffer GF plus 150 μl of buffer CA (20 mM HEPES · KOH pH7.5, 23 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol), with 20 and 60 units of ClaI for 30 minutes at 37°C. Digests were stopped by addition of 2μl 2M TrispH7.5 and 8μl 0.5 M EDTA, treated with RNase A, proteinase K, extracted with phenol and chloroform, and precipitated by adding glycogen, NaCl, and ethanol. The isolated circle DNA was digested with HpaII, fractionated by agarose gel electrophoresis, blotted and hybridized with a circle-specific DNA probe (Figure 2).

Calculations

The probability of finding the cell in state (i,m,n) at time t is given by Pi,m,n (t). The time evolution of Pi,m,n (t) follows from the time-homogenous Markov assumption (1) and the laws of probability:

| (2) |

with Pi,k,l(t) ≡ 0 if k < 0, or l < 0.

This infinite set of coupled differential equations (the “master equation”) can be reduced to a finite system of equations by defining the set of functions Gi, i ∊ S ≡{0,…,7}:

| (3) |

From (2) follows

| (4) |

Inserting equation (2) into (4) gives

| (5) |

We set G(y,z,t) ≡ (G1(y, z, t),…,G7 (y, z, t))T, Γ ≡ (γi, j), and E = (εi, j) with εi,i ≡ εi and εi,j ≡ 0 for all i ≠ j ∈ S. We can now express (5) in vector notation:

| (6) |

Note that Gi (1,1, t) ≡ pi (t) is the probability of finding the promoter in state Ei at time t. We set p(t) ≡ (p0(t), …, p7 (t))T. Obviously ||p(t)||1 = 1 for all t, where is the 1-norm of p(t). The time-evolution of the chromatin transition is determined by Γ; from (6) follows

| (7) |

We assume p(0) = (1,0, …0). We define the generating function G:[0,1]2×R≥0 → R,

| (8) |

The mean values and variances of mRNA and protein molecules can be derived from G according to

| (9) |

(Feller, 1957), where μM(t) is the mean value of mRNA molecules, μN (t) is the mean number of protein molecules, is the variance of mRNA molecules, and is the variance of protein molecules at time t.

The stationary case

As the master equation, the system of equations (5) determines the model completely. However this system, although finite, is not easily solvable (if at all). In this case, predictions can be made using Gillespie’s stochastic simulation algorithm (Gillespie, 1976). On the other hand, the problem of finding mean values and variances for the stationary distribution (Pi,m,n (t) = πi,m,n ∈ [0,1] for all t, i, m, n) can be reduced to a problem in linear algebra (Thattai and van Oudenaarden, 2001), as shown below. By partial differentiation of (6), we obtain two additional equations:

| (10) |

| (11) |

If there is a stationary distribution (πi,m,n), it is uniquely determined and for all i, m, n (Grimmett and Stirzaker, 2001). Thus , , and exist, and by taking the limit for t → ∞, we obtain from (7), (10) and (11) the set of linear equations

| (12) |

where Id is the identity matrix. The stationary mean values μ̄M and μ̄N for mRNA and protein, respectively, can be derived from the solution to (12), since ||v||1 = μ̄M, and ||w||1 = μ̄N, according to (9).

Further partial differentiation of (10) and (11) with respect to y and z, and taking the limit for t → ∞ gives

| (13) |

with , , and . The last two equations of (13) can be combined to eliminate u, which gives

From (9) follows

| (14) |

Thus the stationary probabilities of nucleosome configurations Ei, and the stationary mean values and variances of the gene products can be deduced by solving

| (15) |

Equation systems (7) and (15) were solved numerically using Mathematica. Solutions were transferred into Excel for graphical representation. Monte Carlo simulations were performed in Mathematica (Wolfram Research) using Gillespie’s algorithm (Gillespie, 1976).

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Widom, J. Field, and C. Kaplan for valuable suggestions, J. Z. Sexton and K. Roskin for help with Mathematica, G. Hartzog, A. Gamburd, and E. Robinson for critical comments on the manuscript. H.B. is supported by a Pew Scholars Award. This work was supported by NIH grants GM36659 and GM078111-01 to R.D.K and H.B, respectively, and a travel grant to A.G. and H.B. from the state of Bavaria.

Footnotes

Author Information

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adkins MW, Howar SR, Tyler JK. Chromatin disassembly mediated by the histone chaperone Asf1 is essential for transcriptional activation of the yeast PHO5 and PHO8 genes. Mol Cell. 2004;14:657–666. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almer A, Rudolph H, Hinnen A, Horz W. Removal of positioned nucleosomes from the yeast PHO5 promoter upon PHO5 induction releases additional upstream activating DNA elements. Embo J. 1986;5:2689–2696. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04552.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Even A, Paulsson J, Maheshri N, Carmi M, O’Shea E, Pilpel Y, Barkai N. Noise in protein expression scales with natural protein abundance. Nat Genet. 2006;38:636–643. doi: 10.1038/ng1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbaric S, Reinke H, Horz W. Multiple mechanistically distinct functions of SAGA at the PHO5 promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:3468–3476. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.10.3468-3476.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birney E, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Dutta A, Guigo R, Gingeras TR, Margulies EH, Weng Z, Snyder M, Dermitzakis ET, Thurman RE, et al. Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project. Nature. 2007;447:799–816. doi: 10.1038/nature05874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeger H, Griesenbeck J, Strattan JS, Kornberg RD. Nucleosomes unfold completely at a transcriptionally active promoter. Mol Cell. 2003;11:1587–1598. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00231-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeger H, Griesenbeck J, Strattan JS, Kornberg RD. Removal of promoter nucleosomes by disassembly rather than sliding in vivo. Mol Cell. 2004;14:667–673. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns BR. Chromatin remodeling: insights and intrigue from single-molecule studies. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:989–996. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandy M, Gutierrez JL, Prochasson P, Workman JL. SWI/SNF displaces SAGA-acetylated nucleosomes. Eukaryot Cell. 2006;5:1738–1747. doi: 10.1128/EC.00165-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corona DF, Clapier CR, Becker PB, Tamkun JW. Modulation of ISWI function by site-specific histone acetylation. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:242–247. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote J, Peterson CL, Workman JL. Perturbation of nucleosome core structure by the SWI/SNF complex persists after its detachment, enhancing subsequent transcription factor binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:4947–4952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.4947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dion MF, Kaplan T, Kim M, Buratowski S, Friedman N, Rando OJ. Dynamics of replication-independent histone turnover in budding yeast. Science. 2007;315:1405–1408. doi: 10.1126/science.1134053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feller W. An Introduction to Probability Theory and Its Applications. Vol. 1. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira H, Flaus A, Owen-Hughes T. Histone modifications influence the action of Snf2 family remodelling enzymes by different mechanisms. J Mol Biol. 2007;374:563–579. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.09.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaus A, Owen-Hughes T. Dynamic properties of nucleosomes during thermal and ATP-driven mobilization. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:7767–7779. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.21.7767-7779.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie DT. A general method for numerically simulating the stochastic time evolution of coupled chemical reactions. J Comput Phys. 1976;22:403–434. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie DT. Stochastic simulation of chemical kinetics. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2007;58:35–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.58.032806.104637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory PD, Schmid A, Zavari M, Lui L, Berger SL, Horz W. Absence of Gcn5 HAT activity defines a novel state in the opening of chromatin at the PHO5 promoter in yeast. Mol Cell. 1998;1:495–505. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griesenbeck J, Boeger H, Strattan JS, Kornberg RD. Affinity purification of specific chromatin segments from chromosomal loci in yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:9275–9282. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.24.9275-9282.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griesenbeck J, Boeger H, Strattan JS, Kornberg RD. Purification of defined chromosomal domains. Methods Enzymol. 2004;375:170–178. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(03)75011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimmett G, Stirzaker D. Probability and Random Processes. Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan AH, Neely KE, Workman JL. Histone acetyltransferase complexes stabilize swi/snf binding to promoter nucleosomes. Cell. 2001;104:817–827. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00279-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaskelioff M, Gavin IM, Peterson CL, Logie C. SWI-SNF-mediated nucleosome remodeling: role of histone octamer mobility in the persistence of the remodeled state. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:3058–3068. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.9.3058-3068.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen WJ, Hoose SA, Kilgore JA, Kladde MP. Active PHO5 chromatin encompasses variable numbers of nucleosomes at individual promoters. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:256–263. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin C, Felsenfeld G. Nucleosome stability mediated by histone variants H3.3 and H2A. Z. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1519–1529. doi: 10.1101/gad.1547707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaffman A, Herskowitz I, Tjian R, O’Shea EK. Phosphorylation of the transcription factor PHO4 by a cyclin-CDK complex, PHO80-PHO85. Science. 1994;263:1153–1156. doi: 10.1126/science.8108735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaffman A, Rank NM, O’Shea EK. Phosphorylation regulates association of the transcription factor Pho4 with its import receptor Pse1/Kap121. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2673–2683. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.17.2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassabov SR, Zhang B, Persinger J, Bartholomew B. SWI/SNF unwraps, slides, and rewraps the nucleosome. Mol Cell. 2003;11:391–403. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdistani SK, Grunstein M. Histone acetylation and deacetylation in yeast. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:276–284. doi: 10.1038/nrm1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorch Y, LaPointe JW, Kornberg RD. Nucleosomes inhibit the initiation of transcription but allow chain elongation with the displacement of histones. Cell. 1987;49:203–210. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90561-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorch Y, Maier-Davis B, Kornberg RD. Chromatin remodeling by nucleosome disassembly in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3090–3093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511050103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAndrew PC, Svaren J, Martin SR, Horz W, Goding CR. Requirements for chromatin modulation and transcription activation by the Pho4 acidic activation domain. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5818–5827. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.10.5818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nourani A, Utley RT, Allard S, Cote J. Recruitment of the NuA4 complex poises the PHO5 promoter for chromatin remodeling and activation. Embo J. 2004;23:2597–2607. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paranjape SM, Kamakaka RT, Kadonaga JT. Role of chromatin structure in the regulation of transcription by RNA polymerase II. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:265–297. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.001405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peccoud J, Ycart B. Markovian modelling of gene product synthesis. Theor Popul Biol. 1995;48:222–234. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard KJ, Peterson CL. Chromatin remodeling: a marriage between two families? Bioessays. 1998;20:771–780. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199809)20:9<771::AID-BIES10>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prunell A, Kornberg RD. Relation of nucleosomes to DNA sequences. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1978;42(Pt 1):103–108. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1978.042.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj A, Peskin CS, Tranchina D, Vargas DY, Tyagi S. Stochastic mRNA Synthesis in Mammalian Cells. PLoS Biol. 2006;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raser JM, O’Shea EK. Control of stochasticity in eukaryotic gene expression. Science. 2004;304:1811–1814. doi: 10.1126/science.1098641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinke H, Horz W. Histones are first hyperacetylated and then lose contact with the activated PHO5 promoter. Mol Cell. 2003;11:1599–1607. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00186-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rufiange A, Jacques PE, Bhat W, Robert F, Nourani A. Genome-wide replication-independent histone H3 exchange occurs predominantly at promoters and implicates H3 K56 acetylation and Asf1. Mol Cell. 2007;27:393–405. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha A, Wittmeyer J, Cairns BR. Chromatin remodeling by RSC involves ATP-dependent DNA translocation. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2120–2134. doi: 10.1101/gad.995002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha A, Wittmeyer J, Cairns BR. Chromatin remodeling through directional DNA translocation from an internal nucleosomal site. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:747–755. doi: 10.1038/nsmb973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnitzler G, Sif S, Kingston RE. Human SWI/SNF interconverts a nucleosome between its base state and a stable remodeled state. Cell. 1998;94:17–27. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81217-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svaren J, Horz W. Transcription factors vs nucleosomes: regulation of the PHO5 promoter in yeast. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:93–97. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thattai M, van Oudenaarden A. Intrinsic noise in gene regulatory networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:8614–8619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151588598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas MR, O’Shea EK. An intracellular phosphate buffer filters transient fluctuations in extracellular phosphate levels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9565–9570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501122102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler JK, Adams CR, Chen SR, Kobayashi R, Kamakaka RT, Kadonaga JT. The RCAF complex mediates chromatin assembly during DNA replication and repair. Nature. 1999;402:555–560. doi: 10.1038/990147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venter U, Svaren J, Schmitz J, Schmid A, Horz W. A nucleosome precludes binding of the transcription factor Pho4 in vivo to a critical target site in the PHO5 promoter. Embo J. 1994;13:4848–4855. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06811.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelauer M, Wu J, Suka N, Grunstein M. Global histone acetylation and deacetylation in yeast. Nature. 2000;408:495–498. doi: 10.1038/35044127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workman JL, Kingston RE. Alteration of nucleosome structure as a mechanism of transcriptional regulation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:545–579. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wykoff DD, Rizvi AH, Raser JM, Margolin B, O’Shea EK. Positive feedback regulates switching of phosphate transporters in S. cerevisiae. Mol Cell. 2007;27:1005–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Roberts DN, Cairns BR. Genome-wide dynamics of Htz1, a histone H2A variant that poises repressed/basal promoters for activation through histone loss. Cell. 2005;123:219–231. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Smith CL, Saha A, Grill SW, Mihardja S, Smith SB, Cairns BR, Peterson CL, Bustamante C. DNA translocation and loop formation mechanism of chromatin remodeling by SWI/SNF and RSC. Mol Cell. 2006;24:559–568. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]