Abstract

Knowledge of the pattern of human craniofacial development in the fetal period is important for understanding the mechanisms underlying the emergence of variations in human craniofacial morphology. However, the precise character of the prenatal ontogenetic development of the human cranium has yet to be fully established. This study investigates ontogenetic changes in cranial shape in the fetal period, as exhibited in Japanese fetal specimens housed at Kyoto University. A total of 31 human fetal specimens aged from approximately 8 to 42 weeks of gestation underwent helical computed tomographic scanning, and 68 landmarks were digitized on the internal and external surfaces of the extracted crania. Ontogenetic shape change was then analyzed cross-sectionally and three-dimensionally using a geometric morphometric technique. The results of the present study are generally consistent with previously reported findings. It was found that during the prenatal ontogenetic process, the growth rate of the length of the cranium is greater than that of the width and height, and the growth rate of the length of the posterior cranial base is smaller than that of the anterior cranial base. Furthermore, it was observed that the change in shape of the human viscerocranium is smaller than that of the neurocranium during the fetal period, and that concurrently the basicranium extends by approximately 8° due to the relative elevation of the basilar and lateral parts of occipital bone. These specific growth-related changes are the opposite of those reported for the postnatal period. Our findings therefore indicate that the allometric pattern of the human cranium is not a simple continuous transformation, but changes drastically from before to after birth.

Keywords: cranial base angle, development, fetus, ontogeny, three-dimensional morphometrics

Introduction

Interspecific variations between the craniofacial morphology of humans and non-human primates are thought to have emerged from modifications of the ontogenetic processes during the course of evolutionary history (Enlow, 1966; Krogman, 1974). For example, brain expansion in human evolutionary history and the strong cranial sexual dimorphism found in some primates are both attributed to biological variability in ontogeny. Accordingly, numerous studies in the field of physical anthropology have been conducted to trace the development of cranial shape in humans, specifically changes in shape of the cranial vault and the angulation of the cranial base (e.g. Lieberman & McCarthy, 1999; Ponce de León & Zollikofer, 2001; Williams et al. 2001; Vioarsdottir et al. 2002; Zollikofer & Ponce de León, 2002; Vioarsdottir & Cobb, 2004). The majority of studies have focused on postnatal ontogenetic patterns, but an understanding of the ontogenetic pattern during the prenatal period is of particular importance because distinctive morphogenetic divergence is more concentrated at this stage (Ponce de León & Zollikofer, 2001; Ackermann & Krovitz, 2002; Vioarsdottir et al. 2002; Cobb & O’Higgins, 2004). However, quantitative analyses of the developmental process of the human cranium in the fetal period are relatively rare, due to the limited availability of fetal specimens.

In this study, we carried out a cross-sectional investigation of ontogenetic changes in human cranial shape in the fetal period, using Japanese fetal specimens housed at Kyoto University, Japan. There have been various investigations of human fetal craniofacial growth and development based on sagittally sectioned fetal heads (e.g. Ford, 1956; Birch, 1968; Burdi, 1969; Johnston, 1974) and planar radiographs (e.g. Mestre, 1959; Levihn, 1967; Houpt, 1970; Lavelle, 1974; Trenouth, 1981). However, the ontogenetic changes in cranial shape are actually a complex three-dimensional transformation (Johnston, 1974; Trenouth, 1984; Plavcan & German, 1995), with each element constituting the cranium spatially changing its shape, position and orientation throughout the process. Therefore, for this study, we took observations of the three-dimensional (3D) morphology of the fetal specimens using a helical X-ray CT scanner. The collected data were used to describe quantitatively the changes in size and three-dimensional shape the human cranium undergoes during the whole fetal period using a 3D geometric morphometric technique based on landmark coordinates digitized on the surface of the cranium. We also examined whether sexual dimorphism in cranial shape is already apparent in the fetal period. Based on studies on postnatal ontogeny (e.g. O’Higgins & Collard, 2002; Vioarsdottir et al. 2002), it has been suggested that sexual dimorphism is not present in the prenatal period; therefore, this study directly investigates whether males and females share the same ontogenetic trajectory in the prenatal period. Furthermore, we examine how cranial base angle (CBA) changes prenatally, as it is closely related to the development of cranial capacity and facial morphology, and hence is of great interest to many anatomists and anthropologists (e.g. Lieberman & McCarthy, 1999; Jeffery & Spoor, 2002, 2004; Jeffery, 2003). As some studies have suggested that basicranial flexion is associated with the increase in brain size (Ross & Ravosa, 1993; Ross & Henneberg, 1995; Spoor, 1997), we tested whether the CBA flexes (decreases) in the fetal period. Our results provide a basis for a comparative understanding of the morphogenetic mechanisms underlying the formation of the craniofacial variations specific to humans.

Three-dimensional morphometric techniques of this kind have recently been applied in quantitative analyses of craniofacial ontogenetic patterns both in human and in non-human primates (e.g. Richtsmeier et al. 1993; O’Higgins & Jones, 1998; Ponce de León & Zollikofer, 2001; Vioarsdottir et al. 2002; Zollikofer & Ponce de León, 2002; Bookstein et al. 2003; Cobb & O’Higgins, 2004; Mitteroecker et al. 2004; Leigh, 2006; Cobb & O’Higgins, 2007; Lieberman et al. 2007), and have demonstrated their efficacy. Only Zumpano & Richtsmeier (2003), who studied 3D shape changes in human fetuses aged 22 weeks and over, have used this technique for the prenatal period, and 3D shape change in the early prenatal period has not previously been investigated.

Materials and methods

Human fetal specimens were obtained from the Congenital Anomaly Research Center of Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan. The specimens were preserved in 10% formalin solution after abortion or premature birth between 1967 and 2005 at various hospitals in Japan. Only specimens that were diagnosed free of pathologies and observable postmortem deformation and shrinkage were selected for analysis. The sample contained 13 males and 18 females. Medical histories were not always available, so age was estimated by constructing a regression formula relating biparietal diameter to age. The range of age at death of the specimens used was estimated to be approximately 8–42 weeks of gestation. This should be acceptable in that ossification of the chondrocranium generally begins after 8 weeks of gestation (Scheuer & Black, 2004).

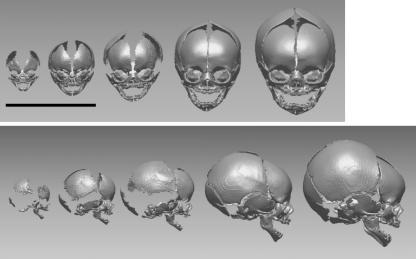

Each fetal specimen was scanned with a helical CT scanner (TSX-002A/4I, Toshiba Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan) at the Laboratory of Physical Anthropology, Kyoto University. Tube voltage, current, and slice thickness were set at 120 kV, 50 or 100 mA, and 1.0 mm, respectively. Cross-sectional images were reconstructed at 0.2-mm intervals, using an FC30 kernel function. The pixel size was 0.35 or 0.20 mm, depending on the size of the specimen. The cross-sectional images were then transferred to commercial software (Analyze 6.0, Mayo Clinic, Minnesota, USA) and the 3D surface of the cranium was reconstructed using a triangular mesh model (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Three-dimensional surface models of human fetal crania representing different gestational ages. Scale bar = 10 cm. The leftmost cranium corresponds to an approximately 8-week-old fetus, and the rightmost corresponds to an approximately 42-week-old fetus.

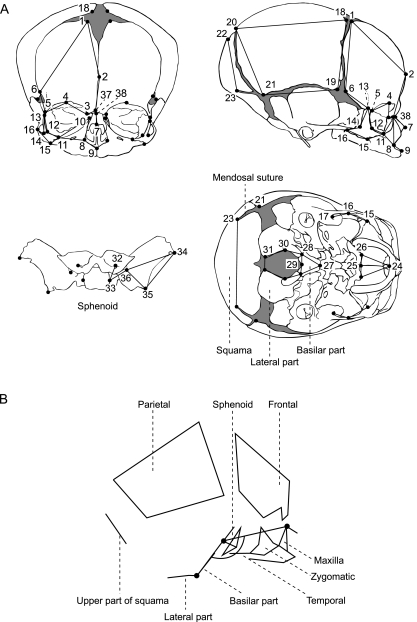

A total of 68 landmarks (Fig. 2, Table 1) were digitized on the surface of each skull using commercial software (Rapidform 2004, INUS Technology, Seoul, Korea). Developmentally homologous points that can be obtained throughout the growth period were chosen as the landmarks. Although a skull is basically symmetrical with respect to the midsagittal plane, the digitized positions of bilateral landmarks are not exactly bisymmetrical. Because we are not concerned with the shape variance due to asymmetry in this study, the positions of all landmarks were symmetrized using the protocol proposed by Zollikofer & Ponce de León (2002).

Fig. 2.

Landmarks and wireframe used in the study. (A) Landmarks. (B) Wireframe approximately defining bone boundaries and three midsagittal points used for calculating the CBA (corresponding to the nasion, sella and basion). See Table 1 for the landmark definitions and text for the calculation of the coordinates of the points. Crania redrawn from Gray (1995).

Table 1.

Landmark definition

| Number | Definition | Type |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Most supero-medial point on the parietal angle of the right (left) half of frontal bones contacting with anterior fontanelle | B |

| 2 | Most pronounced anterior point on the medial margin of the right (left) half of frontal bone in the lateral view | B |

| 3 | Most infero-medial point on the superior orbital rim of frontal bone | B |

| 4 | Most superior point on the superior orbital rim of frontal bone | B |

| 5 | Most infero-lateral point on the superior orbital rim of frontal bone | B |

| 6 | Most posterior point on the infero-lateral angle of the the right (left) half of frontal bones contacting with sphenoidal fontanelle | B |

| 7 | Midline point on the inferior-most margin of nasal bone | M |

| 8 | Alare | B |

| 9 | Midpoint between the superior-most points of the inferior nasal aperture margin | M |

| 10 | Most superior point on the frontal process of maxilla | B |

| 11 | Most medial point on the maxillary process on the inferior orbital rim of zygomatic bone | B |

| 12 | The point on the inferior orbital rim of zygomatic bone in the depth of the notch between frontal and maxillary processes | B |

| 13 | Most superior point on the frontal process of zygomatic bone | B |

| 14 | Jugale | B |

| 15 | Zygomaxillare | B |

| 16 | Most posterior point on the temporal process of zygomatic bone | B |

| 17 | The point in the depth of the notch between the zygomatic process and the squama of temporal bone | B |

| 18 | Most supero-anterior point on the frontal angle of the right (left) half of parietal bones contacting with anterior fontanelle | B |

| 19 | Most anterior point on the sphenoidal angle of the right (left) half of parietal bones contacting with sphenoidal fontanelle | B |

| 20 | Most posterior point on the occipital angle of the right (left) half of parietal bones contacting with posterior fontanelle | B |

| 21 | Most posterior point on the mastoid angle of the right (left) half of parietal bones contacting with mastoid fontanelle | B |

| 22 | The point on the closing end of the superior median fissure of the squama of occipital bone | M |

| 23 | The point on the closing end of the sutura mendosa of the squama of occipital bone | B |

| 24 | Most antero-medial point on the palatine process of maxilla | M |

| 25 | Most postero-medial point on the horizontal plate of palatine bone | M |

| 26 | Most anterior point on the posterior curvature of horizontal plate of the right (left) half of palatine bone | B |

| 27 | Central point on the surface for sphenoid bone of the basilar part of occipital bone | M |

| 28 | The most prominent point on the junction between surfaces for condylar and jugular limbs of the basilar part of occipital bone | B |

| 29 | Basion | M |

| 30 | Most lateral point on the lateral margin of the foramen magnum | B |

| 31 | Most prominent point on the angle formed between surfaces for foramen magnum and supra-occipital of the lateral part of occipital bone | B |

| 32 | Most lateral point on the optic canal of lesser wing of sphenoid bone | B |

| 33 | Middle point on the lateral side of the superior surface of the postsphenoid part of body of sphenoid bone | B |

| 34 | Most antero-lateral point on the greater wing of sphenoid bone | B |

| 35 | Most infero-lateral point on the greater wing of sphenoid bone | B |

| 36 | Most inferior point on the foramen rotundum of sphenoid bone | B |

| 37 | Most medial point on the infero-medial angle of the right (left) half of frontal bone | B |

| 38 | Midline point on the superior margin of nasal bone | M |

M = midsagittal, B = bilateral.

To describe the growth-related shape changes in the cranium, the 3D coordinates of the landmarks were analyzed using the geometric morphometric software Morphologika, version 2.3.1 (O’Higgins & Jones, 2006). The landmark coordinates of each specimen were normalized by centroid size (CS) and registered using the Generalized Procrustes method (Rohlf & Slice, 1990). The principal components (PCs) of the shape variations among the specimens, that is, the Procrustes residuals, were then calculated, and the shape changes along the principal axes were visualized using the software, as above. Statistical analyses were carried out in a linear tangent space (see O’Higgins & Jones (1998) for more details of the calculation method).

The midsagittal angle of the cranial base was calculated using the midpoints of three bilateral landmark pairs, #38, #33 and #29, which approximately correspond to the nasion, the center of the sella turcica (sella) and the basion, respectively. In a precise sense, landmark #38, located on the nasal bone, is not part of the cranial base, but this is the most stable landmark that can feasibly be digitized for defining the anterior cranial base. Slight differences in the definition of the CBA result in large differences in the absolute values of the CBA, but the ontogenetic trends of the angle have been shown to be quite consistent (George, 1978; Lieberman & McCarthy, 1999).

Results

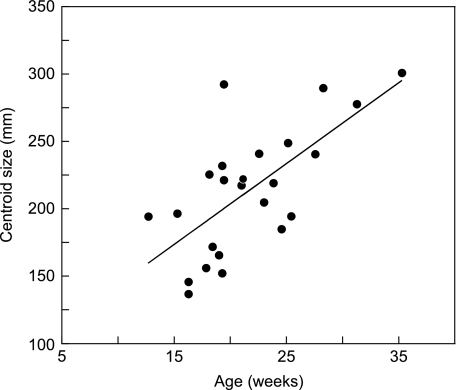

The CS of all fetal specimens is plotted against age at death in Fig. 3. CS increases linearly with age in the period investigated and there is a significant correlation between the two (r = 0.68, P < 0.01).

Fig. 3.

Relationship between gestational age and CS. Seven fetal specimens whose medical histories were not available are not included. Age and CS are significantly correlated.

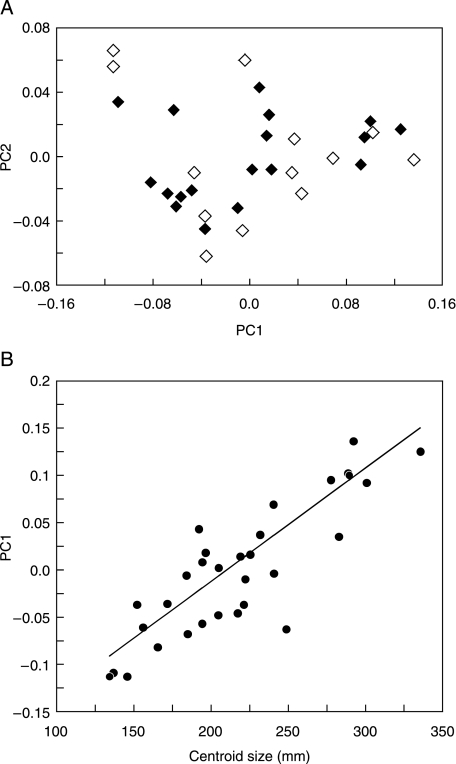

The results of the principal components analysis (PCA) are shown in Fig. 4 as the plot of PC1 (the first principal component) vs. PC2. The origin in each plot represents the mean shape, and the plotted points represent the shape of each specimen. PC1 accounts for 48% of the total variance, PC2 for 10%, and the first five PCs for 75%. To examine the relationship between size and shape, we plotted the PC scores against CS, as shown in Fig. 4. Each of the PCs is statistically independent. Thus each PC can be examined for significant correlations with external variables. Only PC1 exhibits a significant linear relationship with CS (r = 0.86, P < 0.01; Fig. 4B), whereas the other higher PCs do not, indicating that size-related shape variation is largely if not completely represented by PC1, the other PCs representing shape variation independent of growth. Males and females do not fall into two groups in this plot and in the higher dimensional space, indicating that there are no significant differences in either cranial shape or ontogenetic trajectory in the prenatal period.

Fig. 4.

Principal components analysis of the fetal crania. (A) Plots of the PC1 vs. PC2 scores. Black diamond = female, white diamond = male. (B) The relationship between CS and PC1. These variables are significantly correlated.

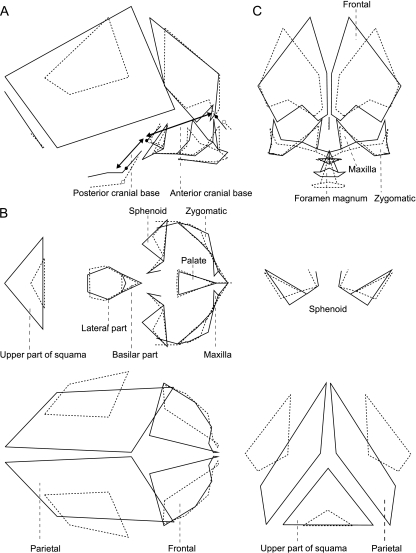

In Fig. 5, the aspects of 3D shape variation represented by PC1 are visualized by deforming cranial shape along PC1 (other PCs = 0). PC1 scores increase with the CS as illustrated in Fig. 4. The dotted wireframe, with PC1 = – 0.12, indicates cranial shape in the early stages of pregnancy (approximately 8 weeks of gestation), whereas the solid wireframe, with PC1 = 0.16, represents shape in late pregnancy (approximately 42 weeks). The figure clearly illustrates that the cranium shows relative contraction in the medio-lateral and supero-inferior directions, but expansion in the antero-posterior direction. This means that antero-posterior length increases faster than height and width during fetal development. It was also observed that the length of the posterior cranial base relatively contracts due to the elevation of the basilar part of the occipital bone relative to other cranial structures, whereas that of the anterior cranial base remains relatively constant. As a whole, the shape change in the neurocranium is relatively larger than that in the viscerocranium. The shapes and the relative positions of the facial bones, such as the maxillae and zygomatics, change little during the prenatal period, but a considerable posterior elongation of the occipital region (the supratentorial part) with respect to the position of the foramen magnum is observed. In the facial region, the orbital area becomes more posteriorly placed relative to the rest of the face. In the coronal plane, it is observed that the width of the posterior part of the cranium becomes relatively contracted, whereas that of the anterior part remains relatively constant. In addition, the distance between the optic canals becomes relatively narrower during fetal development.

Fig. 5.

Shape change of the fetal cranium. (A) Sagittal view. (B) Horizontal view. (C) Coronal view. Wireframes drawn by dashed and solid lines correspond to an 8-week-old and a 42-week-old fetus, respectively.

To describe the composite allometric trajectory, we also performed a multivariate regression analysis using the first 29 PCs, which account for over 99% of variance, as the dependent variables and ln (CS) as the independent variable. The results of the present multivariate regression analysis were found to be very consistent with the results presented in Fig. 5.

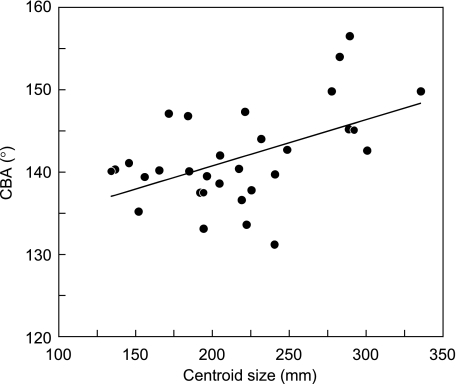

The CBA was calculated on two virtual crania corresponding to an approximately 8-week-old (PC1 = –0.12) and a 42-week-old (PC1 = 0.16) fetus. The calculated CBAs were 138.6° and 146.6°, respectively, indicating an increase of approximately 8° during the fetal period. The CBA of all specimens is plotted against CS in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Relationship between CS and CBA. These variables are significantly correlated (r = 0.51, P < 0.01).

Discussion

This study successfully illustrates the existence of comprehensive 3D shape changes in the human cranium in the prenatal period, using computed tomography and geometric morphometric analysis. Early hypotheses held that craniofacial shape is more or less invariant during fetal life (Burdi, 1969; Johnston, 1974; Lavelle, 1974), but later studies have suggested, and the present study confirms, that craniofacial development of the human fetus is a complex non-linear morphological transformation.

The results of the present study are generally consistent with previously reported findings. It was found that, during the prenatal ontogenetic process, 1) the growth rate of the length of the cranium is greater than that of the width and height, as has been suggested previously (Houpt, 1970; Trenouth, 1984; Zumpano & Richtsmeier, 2003); 2) the growth rate of the length of the posterior cranial base is smaller than that of the anterior cranial base (Mestre, 1959; Levihn, 1967; Birch, 1968; Johnston, 1974); and 3) the cranial base retroflexes, in accordance with most accounts in previous literature (Ford, 1956; Mestre, 1959; Dimitriadis et al. 1995; Jeffery & Spoor, 2004).

However, our results contradict Zumpano & Richtsmeier's (2003) CT-based morphometric study of craniofacial form change in several respects. They reported that the width of the fetal cranium increases disproportionately and the CBA decreases (flexes) during the fetal period. Although the former discrepancy could be attributed to the use of different set of anatomical landmarks in their analyses and to the fact that shape rather than form (size plus shape) is examined in the present analysis, the source of the latter discrepancy is obscure and we can offer no explanation at present.

In this study, the three above-mentioned characteristics are mutually related. During the fetal period, the shape of the cranium primarily elongates (i.e. antero-posterior dimensions increase at a greater rate than medio-lateral or supero-inferior). Thus relative cranial height and length of the posterior cranial base are reduced, and the relative position of the basion is shifted upward, with the consequence that the cranial base flattens. Therefore, this study suggests that the retroflexion of the cranial base is closely linked to the relative antero-posterior enlargement of the neurocranial region with respect to the viscerocranial region. Although it has been suggested that basicranial flexion is related to increase in brain size (Ross & Ravosa, 1993; Ross & Henneberg, 1995; Spoor, 1997), this study suggests that basicranial retroflexion in prenatal ontogeny is primarily linked to brain expansion. Indeed, the finding that the basicranium retroflexes with increased brain size in the fetal ontogeny of macaque and howler monkey (Jeffery, 2003) suggests that this process might be common to primates during the fetal period. A recent study of tarsier by Jeffery et al. (2007) suggests that such a common trend of fetal retroflexion is confined with brain expansion. As a future issue, it would be a highly interesting challenge to directly describe the three-dimensional form change of human brain during prenatal ontogeny and analyze mutual morphological interrelationships between the hard and soft tissues.

The present study also confirmed that there are no major differences in either cranial shape or ontogenetic trajectory between males and females in the prenatal period as suggested previously by Houpt (1970). Sexual dimorphism in human cranial shape becomes clearly visible by the time of puberty and adolescence (Ursi et al. 1993; Rosas & Bastir, 2002; Bulygina et al. 2006). This study suggests that such cranial dimorphism emerges due to the divergence of ontogenetic trajectories after birth, probably in early postnatal development (Vioarsdottir et al. 2002).

It should be noted that our observed cranial ontogenetic patterns in prenatal ontogeny are the reverse of those in postnatal ontogeny. Equivalent data on postnatal craniofacial shape changes indicate that the CBA decreases (flexes) until about 2 years of age (George, 1978; Lieberman & McCarthy, 1999), and that the neurocranium undergoes relative contraction, whereas the viscerocranial region expands from 3 years old to adulthood (Zollikofer & Ponce de León, 2002). Thus, the ontogeny of the human cranium is not a simple continuous transformation, but changes drastically from before to after birth. The functional significance of this inversion of the craniofacial ontogenetic pattern remains to be elucidated, but it could be related to the developmental constraints imposed on the fetal cranium for safe passage through the birth canal during childbirth. Obtaining postnatal specimens for the period from birth to 2 years of age is difficult, but comparing allometric patterns or tracing ontogenetic trajectory for the pre- and postnatal periods together using the same method would be an interesting area for future studies.

The 3D prenatal ontogenetic shape changes in the human cranium described here can serve as a basis for a comparative understanding of developmental mechanisms involved in producing craniofacial variability among various primate taxa, including humans. Interspecific comparisons of the ontogenetic trajectory of this sample with those of other primates will help clarify the limits of the universality and specificity in primate craniofacial morphogenesis demonstrated by Zumpano & Richtsmeier (2003). However, some methodological limitations certainly exist. For example, as younger specimens are more cartilaginous, they are more easily distorted due to shrinkage. Therefore, although we attempted to avoid distorted materials, the results of the present shape analysis might contain some shrink-related shape artifacts. In addition, as only ossified bones were visualized using CT, the extracted growth-related shape change only partly reflects gradual ossification of shape-invariant cartilaginous precursors rather than actual morphological changes. It should also be borne in mind that the present analysis extracts the changes in craniofacial geometry as a linear, monotonic process over time, whereas in fact the rate of growth changes over time and differs from region to region of the human skull. To capture the non-linear heterochronic processes involved in the development of craniofacial morphology, time-variable ontogenetic trajectories (that is, changes in the spatial position of the landmarks employed over time) must be identified to create a spatiotemporal growth model (e.g. Zollikofer & Ponce de León, 2004). We intend to proceed in this direction hereafter.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the members of the Laboratory of Physical Anthropology and the Congenital Anomaly Research Center, Kyoto University, especially Hidemi Ishida, Masato Nakatsukasa and Chikako Uwabe, for their continuous guidance and support throughout the course of the present study. We also sincerely thank Christoph Zollikofer and Marcia Ponce de León of the Anthropological Institute, University of Zurich, and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive and thoughtful comments. This study was supported in part by a JSPS Grant in Aid for Scientific Research (#19370101) to NO.

References

- Ackermann RR, Krovitz GE. Common patterns of facial ontogeny in the hominid lineage. Anat Rec. 2002;269:142–147. doi: 10.1002/ar.10119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch RH. Foetal retrognathia and the cranial base. Angle Orthod. 1968;38:231–235. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1968)038<0231:FRATCB>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookstein FL, Gunz P, Mitteroecker P, Prossinger H, Schaefer K, Seidler H. Cranial integration in Homo: singular warps analysis of the midsagittal plane in ontogeny and evolution. J Hum Evol. 2003;44:167–187. doi: 10.1016/s0047-2484(02)00201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulygina E, Mitteroecker P, Aiello L. Ontogeny of facial dimorphism and patterns of individual development within one human population. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2006;131:432–443. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdi AR. Cephalometric growth analyses of the human upper face region during the last two trimesters of gestation. Am J Anat. 1969;125:113–122. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001250106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb SN, O’Higgins P. Hominins do not share a common postnatal facial ontogenetic shape trajectory. J Exp Zoolog B Mol Dev Evol. 2004;302:302–321. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.21005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb SN, O’Higgins P. The ontogeny of sexual dimorphism in the facial skeleton of the African apes. J Hum Evol. 2007;53:176–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitriadis AS, Haritanti-Kouridou A, Antoniadis K, Ekonomou L. The human skull base angle during the second trimester of gestation. Neuroradiology. 1995;37:68–71. doi: 10.1007/BF00588524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enlow DH. A comparative study of facial growth in Homo and Macaca. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1966;24:293–308. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330240303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford EH. The growth of the foetal skull. J Anat. 1956;90:63–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George SL. A longitudinal and cross-sectional analysis of the growth of the postnatal cranial base angle. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1978;49:171–178. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330490204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray H. Gray's Anatomy. 38. Oxford: Churchill Livingstone; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Houpt MI. Growth of the craniofacial complex of the human fetus. Am J Orthod. 1970;58:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(70)90108-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery N. Brain expansion and comparative prenatal ontogeny of the non-hominoid primate cranial base. J Hum Evol. 2003;45:263–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery N, Spoor F. Brain size and the human cranial base: a prenatal perspective. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2002;118:324–340. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.10040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery N, Spoor F. Ossification and midline shape changes of the human fetal cranial base. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2004;123:78–90. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.10292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery N, Davies K, Kockenberger W, Williams S. Craniofacial growth in fetal Tarsius bancanus: brains, eyes and nasal septa. J Anat. 2007;210:703–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2007.00725.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LE. A cephalometric investigation of the sagittal growth of the second-trimester fetal face. Anat Rec. 1974;178:623–630. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091780309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogman WM. Craniofacial growth and development: an appraisal. Yearb Phys Anthropol. 1974;18:31–64. [Google Scholar]

- Lavelle CL. An analysis of foetal craniofacial growth. Ann Hum Biol. 1974;1:269–287. doi: 10.1080/03014467400000311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh SR. Cranial ontogeny of Papio baboons (Papio hamadryas) Am J Phys Anthropol. 2006;130:71–84. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levihn WC. A cephalometric roentgenographic cross-sectional study of the craniofacial complex in fetuses from 12 weeks to birth. Am J Orthod. 1967;53:822–848. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(67)90089-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman DE, McCarthy RC. The ontogeny of cranial base angulation in humans and chimpanzees and its implications for reconstructing pharyngeal dimensions. J Hum Evol. 1999;36:487–517. doi: 10.1006/jhev.1998.0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman DE, Carlo J, Ponce de León M, Zollikofer CP. A geometric morphometric analysis of heterochrony in the cranium of chimpanzees and bonobos. J Hum Evol. 2007;52:647–662. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mestre JC. A cephalometric appraisal of cranial and facial relationships at various stages of human fetal development. Am J Orthod. 1959;45:473. [Google Scholar]

- Mitteroecker P, Gunz P, Bernhard M, Schaefer K, Bookstein FL. Comparison of cranial ontogenetic trajectories among great apes and humans. J Hum Evol. 2004;46:679–697. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Higgins P, Collard M. Sexual dimorphism and facial growth in papionin monkeys. J Zool. 2002;257:255–272. [Google Scholar]

- O’Higgins P, Jones N. Facial growth in Cercocebus torquatus: an application of three-dimensional geometric morphometric techniques to the study of morphological variation. J Anat. 1998;193(Pt 2):251–272. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.1998.19320251.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Higgins P, Jones N. Tools for statistical shape analysis. 2006. Hull York Medical School, http://www.york.ac.uk/res/fme/resources/software.htm.

- Plavcan JM, German RZ. Quantitative evaluation of craniofacial growth in the third trimester human. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1995;32:394–404. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569_1995_032_0394_qeocgi_2.3.co_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponce de León MS, Zollikofer CP. Neanderthal cranial ontogeny and its implications for late hominid diversity. Nature. 2001;412:534–538. doi: 10.1038/35087573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richtsmeier JT, Corner BD, Grausz HM, Cheverud JM, Danahey SE. The role of postnatal growth pattern in the production of facial morphology. Syst Biol. 1993;42:307–330. [Google Scholar]

- Rohlf FJ, Slice D. Extensions of the Procrustes method for the optimal superimposition of landmarks. Syst Zool. 1990;39:40–59. [Google Scholar]

- Rosas A, Bastir M. Thin-plate spline analysis of allometry and sexual dimorphism in the human craniofacial complex. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2002;117:236–245. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.10023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross C, Henneberg M. Basicranial flexion, relative brain size, and facial kyphosis in Homo sapiens and some fossil hominids. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1995;98:575–593. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330980413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CF, Ravosa MJ. Basicranial flexion, relative brain size, and facial kyphosis in nonhuman primates. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1993;91:305–324. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330910306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuer L, Black S. Developmental Juvenile Osteology. London: Academic Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Spoor F. Basicranial architecture and relative brain size of Sts 5 (Australopithecus africanus) and other Plio-Pleistocene hominids. S Afr J Sci. 1997;93:182–187. [Google Scholar]

- Trenouth MJ. Angular changes in cephalometric and centroid planes during foetal growth. Br J Orthod. 1981;8:77–81. doi: 10.1179/bjo.8.2.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trenouth MJ. Shape changes during human fetal craniofacial growth. J Anat. 1984;139(Pt 4):639–651. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ursi WJ, Trotman CA, McNamara JA, Jr, Behrents RG. Sexual dimorphism in normal craniofacial growth. Angle Orthod. 1993;63:47–56. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1993)063<0047:SDINCG>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vioarsdottir US, Cobb S. Inter- and intra-specific variation in the ontogeny of the hominoid facial skeleton: testing assumptions of ontogenetic variability. Ann Anat. 2004;186:423–428. doi: 10.1016/s0940-9602(04)80076-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vioarsdottir US, O’Higgins P, Stringer C. A geometric morphometric study of regional differences in the ontogeny of the modern human facial skeleton. J Anat. 2002;201:211–229. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00092.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams FL, Godfrey LR, Sutherland MR. Heterochrony and the evolution of Neanderthal and modern human craniofacial form. In: Minugh-Purvis N, McNamara K, editors. Human Evolution through Developmental Change. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2001. pp. 405–441. [Google Scholar]

- Zollikofer CP, Ponce De León MS. Visualizing patterns of craniofacial shape variation in Homo sapiens. Proc Biol Sci. 2002;269:801–807. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zollikofer CP, Ponce de León MS. Kinematics of cranial ontogeny: heterotopy, heterochrony, and geometric morphometric analysis of growth models. J Exp Zoolog B Mol Dev Evol. 2004;302:322–340. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.21006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zumpano MP, Richtsmeier JT. Growth-related shape changes in the fetal craniofacial complex of humans (Homo sapiens) and pigtailed macaques (Macaca nemestrina): a 3D-CT comparative analysis. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2003;120:339–351. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.10125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]