Abstract

Personality traits and risk perceptions were examined as predictors of changes in smoking behavior. Participants (N = 697) were part of a randomized controlled trial of interventions to reduce exposure to the combined hazard of radon and cigarette smoke. Participants with higher perceived risk at baseline for the combination of smoking and radon were more likely to have a more restrictive household smoking ban in place at 12 months follow-up (p <. 05). Risk perceptions also predicted reductions in the total number of cigarettes smoked in the home for participants in the video intervention who had high or moderate levels of Extraversion (p <.001). Greater perceived risk predicted quitting for highly or moderately conscientious women (p <.05). The moderating effects of personality traits should be considered when evaluating risk-reduction interventions.

Keywords: smoking, Big Five, perceived risk, health behavior, radon

Radon is a naturally occurring, radioactive gas that seeps out of rocks and soil and can accumulate in houses depending on the underlying geology and way the home is built. The inhalation of radioactive atoms formed by the break down of radon in the air has been identified as the second leading cause of lung cancer in the USA after cigarette smoking (Environmental Protection Agency, 1992). Furthermore, it is conservatively estimated that exposure to average levels of home radon in combination with smoking increases the smoker’s risk of lung cancer at least ten-fold (Committee on Health Risks of Exposure to Radon, 1999; Reif & Heeran, 1999). In an earlier study, we evaluated interventions that used the health threat from low levels of radon in combination with smoking to change smoking in the home (Lichtenstein, Andrews, Lee, Glasgow, & Hampson, 2000). We also examined the effects of the perceived risk of the combination of radon and smoking, and the personality trait of Conscientiousness, on changes in smoking behavior (Hampson, Andrews, Barckley, Lichtenstein, & Lee, 2000). Here, we extend this earlier work in the context of a further intervention study by investigating the influences of three of the broad personality traits in the five-factor (Big Five) model, and the perceived risk of radon and smoking, on changes in smoking behaviors. We investigate whether these individual differences moderate the effects of the interventions developed for this new study. Identifying personality moderators should lead to more powerful interventions by targeting based on personality assessment and tailoring of materials to individual differences (e.g., Williams-Piehota, Pizarro, Schneider, Mowad, & Salovey, 2005).

In the earlier study, both interventions (brief telephone counseling and/or written information about the health risks of radon and smoking) led to more household bans on smoking (Lichtenstein et al., 2000). The effects of these interventions were not moderated by the level of perceived risk of radon combined with smoking, or Conscientiousness. However, across interventions, more conscientious individuals were more likely to adopt more restrictive household smoking rules. Furthermore, the effect of perceived risk of the combination of radon and smoking on a reduction in cigarettes smoked in the home was moderated by Conscientiousness: perceived risk predicted a reduction only for those who were highly conscientious individuals. Neither perceived risk nor Conscientiousness predicted quitting smoking (Hampson et al., 2000). The present study extended the earlier one by (1) developing a potentially more powerful video intervention, (2) examining the influence of Extraversion and Emotional Stability as well as Conscientiousness as moderators of intervention condition and risk perceptions, and (3) using a more sensitive measure of perceived risk.

The study was conducted as part of a randomized controlled trial of households in Western Oregon with at least one smoker and average to low levels of radon. Each household was represented by one participant, who may or may not have been a smoker. Participants initially received the same brief information about the health risks of radon and smoking. They engaged in home radon testing, and were sent their results along with written materials about radon and smoking. Participants were randomly assigned to the video condition, or telephone counseling, both components, or neither. The 15-minute video used graphics to show the way smoking increases the effects of radon on the lungs, and depicted a family reviewing the results of their radon test and discussing what to do. The family agreed to a new ban on smoking in the house, the father reduced the number of cigarettes he smoked, and the mother quit smoking. The telephone counseling consisted of one or two brief calls clarifying the risks of radon exposure and smoking, and encouraging quitting or not smoking indoors.

A separate report on the effects of these interventions on various smoking outcomes is currently underway (Lichtenstein, Lee, Boles, Hampson, & Glasgow, in preparation). The present report examines the relation of participants’ personality traits and their perceived risk of the combination of smoking and radon to two household-level outcomes (more restrictive smoking bans in the home, and reduction in the number of cigarettes smoked by anyone in the home), and one individual-level variable (smoking cessation among smoking respondents only), evaluated at 12 months follow-up. Three traits from the five-factor model of personality were investigated (Digman, 1990; Goldberg, 1993; John & Srivistava, 1999): Extraversion (e.g., dominant, sociable vs. submissive, shy), Conscientiousness (e.g., organized, planful vs. impulsive, unreliable), and Emotional Stability (e.g., calm, stable vs. anxious, moody). Personality traits and risk perceptions were expected to moderate the effects of the interventions on household- and individual-level smoking outcomes. The interventions were designed to motivate risk-reduction behaviors, and individuals with higher levels of the traits, or higher levels of perceived risk, were expected to be particularly responsive to the intervention messages, and thus to report larger intervention effects on both household-level and individual-level outcomes.

For the household-level outcomes, more highly extraverted respondents may be more successful at changing household smoking in response to the interventions because Extraversion includes interpersonal and leadership skills, and is associated with more use of a wider range of social-influence strategies (Buss, 1992; Caldwell & Burger, 1997). Highly conscientious individuals are dutiful, persevering and planful, and use the social-influence strategy of reasoning with others (Buss, 1992). These qualities should help such individuals to carry out the household-level changes suggested in the intervention materials. It was also possible that highly emotionally stable respondents would respond calmly and without undue negative affect to the health threat conveyed by the intervention messages, and thus would be more likely to achieve beneficial changes on household outcomes.

Predictions for the moderating effects of personality traits on the effects of the interventions on the individual-level outcome of smoking cessation were guided by past research on the personality traits of smokers and successful quitters. It was expected that the intervention message to quit smoking as a way of reducing the threat from radon and smoking would be less effective for individuals with personality traits associated with continued smoking. Extraversion is associated with smoking (although the strength of this association appears to have decreased in more recent years, Gilbert, 1995), so more extraverted respondents were expected to be less responsive to the interventions and hence less likely to quit than those who were more introverted (Helgason, Fredikson, Dyba, & Steineck, 1995). More conscientious individuals engage in more health-enhancing and fewer health-damaging behaviors, including less tobacco use (Bogg & Roberts, 2004), and conscientious individuals tend to live longer (Friedman et al., 1995). Therefore, more conscientious individuals were expected to be more likely to quit in response to the interventions. Emotional Stability has been negatively associated with smoking in numerous studies (Gilbert, 1995) and smoking appears to help with mood regulation for more neurotic individuals (Joseph, Manaki, Iakovaki, & Cooper, 2003; McChargue, Cohen, & Cook, 2004), so less emotionally stable (i.e., more neurotic) smoker responders were predicted to be less likely to quit in response to the interventions.

Consistent with the precaution adoption process model (Weinstein & Sandman, 1992) and other social cognition models of health behavior (Conner & Norman, 1996), individuals with higher levels of perceived risk of the combination of smoking and radon should be more likely to take the actions advocated by the interventions to reduce the risk from radon and smoking. However, risk perceptions may only influence smoking outcomes for individuals with higher levels of Extraversion, Conscientiousness, and Emotional Stability if these personality characteristics are necessary for the perception of the health risk to bring about behavior change. Therefore, the interactions of each personality trait with risk perceptions were examined. Because of their previous associations with smoking and risk perceptions, we also controlled for the effects of education, and examined the interactive effects of age and gender (Hampson et al., 2000; Ockene et al., 2000; Slovic, 1992).

Method

Participants and Recruitment

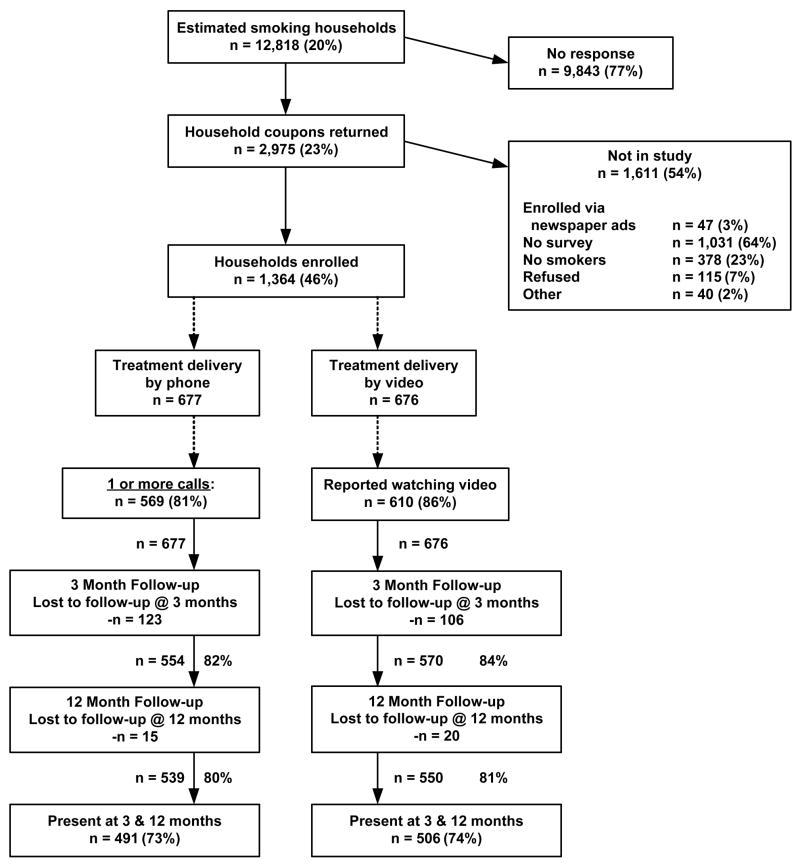

A coupon offering a free radon test kit to households with at least one smoker was included in the bills mailed by several utilities in Western Oregon (for details, see Glasgow, Boles, Lichtenstein, Lee, & Foster, 2004). The 2,975 households returning the coupon were sent a radon kit along with a baseline survey. The 1,364 eligible households were then randomized to condition (see Figure 1). Each household was represented by one participant who reported on the smoking behavior of everyone in the household. Follow-up surveys were sent to the same named individual who had requested the radon test kit but may have been completed by another member of the household. Therefore, for this report, the sample was restricted to households for which the same respondent completed the baseline, 3 and 12 month surveys, and also to those who had not tested their home for radon before the study, and who did test for radon between the baseline and 3-month follow-up assessments1. In addition, we excluded data from 73 respondents who did not appear to understand the risk perception rating scale (see below). This reduced eligible respondents to 697. At baseline, there were no differences between these 697 and the remaining households in terms of age of the respondent, smoking status of the respondent, proportion of households with smoking bans or rules regarding smoking in the home, and average number of cigarettes smoked in the home. However, this subsample included a significantly higher proportion of women (56.3%) than the remaining households (50.5%), Chi Square (1, n = 1341) = 4.61, p <.05.

Figure 1.

CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) flow diagram summarizing participant progress through the phases of the randomized trial.

Measures

All measures were administered by mailed surveys at baseline, 3 and 12 months follow-up, except for the personality assessment, which was conducted once only at the 3 months follow-up.

Personality traits

Respondents completed a personality measure using items from the BFI-44, a comprehensive measure of the five-factor model of personality (John, Donahue, & Kentle, 1991). The mean ratings (5-point scale) for each of the three traits were calculated. Internal consistencies (coefficient alpha) were: Extraversion = .74, Conscientiousness = .76, and Emotional Stability = .72. The personality scales were modestly intercorrelated (Extraversion and Conscientiousness, r = .14; Extraversion and Emotional Stability, r = .19; Conscientious and Emotional Stability, r = .28).

Risk perceptions

Respondents rated the health risk of each hazard (radon, smoking, and the combination of radon and smoking) on a scale that, when used correctly, has been shown to be more sensitive to the increased combined risk than a traditional Likert scale (Hampson, Andrews, Barckley, Lee, & Lichtenstein, 2003). Health risk was rated relative to the risk from drinking 5 alcoholic drinks per day, which defined the mid-point of the scale. Steps above and below the mid-point were labeled to reflect multiplicative increases or decreases in risk to health (1 = “Many times less risky,” 2 = “About half as risky,” 3 = “Somewhat less risky,” 4 = “About as risky as 5 drinks per day,” 5 = “Somewhat more risky,” 6 = “About twice as risky,” and 7 = “Many times more risky”). To check that respondents were using this scale correctly, they were asked to rate the risk of 1–2 alcoholic drinks per day, which should be rated below the midpoint. The 73 respondents who rated this item at or above the mid-point were excluded. The perceived risk of the combination of radon and smoking at baseline was used in the analyses2.

Smoking outcomes

Household smoking rules were assessed by a single item asking respondents to select the statement that best described the current smoking rules in their home: No rules, partial ban (i.e., no smoking when certain people are present or smoking restricted to certain areas in the house), or a complete ban on smoking in the house. Responses at baseline and 12 months follow-up were compared to determine whether or not the household had adopted a more restrictive rule to create a dichotomous outcome variable. For each household resident, including themselves, the respondents indicated whether they currently smoked cigarettes even occasionally and, if so, how many they smoked in the house on a typical day. From this information, the total number of cigarettes smoked daily in the house was calculated and smoking cessation at 12 months by responders who smoked at baseline was determined.

Overview of Analyses

We used multiple logistic regression to predict change to a more restrictive household rule and the respondents’ quitting at the 12-month follow-up, and hierarchical multiple linear regression to predict total number of cigarettes smoked in the house at 12 months, controlling for total number of cigarettes smoked in the home at baseline. Of the 697 eligible participants, 14.5% failed to complete the personality and/or the risk- perception measures. These scores were not imputed because they may have been missing for personality-based reasons. For analyses predicting change to a more restrictive household rule, the sample was limited to those who had no ban or only a partial ban at baseline (n = 380); for analyses predicting reduction in cigarettes smoked in the home, n = 517; and for analyses predicting quit, the sample was limited to those respondents who smoked at baseline (n = 367).

Potential predictors included each intervention condition (video vs. no-video; telephone counseling vs. no counseling), the three personality variables, perceived risk of smoking and radon at baseline, gender, and age, as well as their interactions. Education was included as a control variable only. Because of the large number of potential interactions, preliminary analyses were conducted to reduce the number of interactions evaluated in the final model. We also did not test any four-way interactions. In these preliminary analyses, we explored the two-way interactions of age and gender with personality variables and risk and found all two-way interactions with age to be non-significant and therefore included age as a main effect only. In addition, the effect of the two-way interaction between the two intervention conditions on each outcome was found to be non-significant so was not tested further. Next, in separate analyses, we evaluated the relation between each outcome and the three-way interaction between each personality variable, gender and risk perceptions, the three-way interaction between each personality variable, perceived risk and the intervention condition, the three-way interaction between each intervention condition, each personality variable and gender, and the three-way interaction between each intervention condition, perceived risk and gender. Lower order interactions were included in each analysis, and if the three-way interaction was not significant, these were then evaluated for significance.

To arrive at a final model, all main effects and significant interactions identified in the preliminary analyses were entered into a combined model and non-significant interactions were removed from the combined model using backward elimination, starting with the higher-order interactions (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003). All non-significant main effects were removed except for age, education, and gender and those main effects that were a part of a significant interaction. Significant interactions were examined using procedures recommended by Aiken and West (1991). To examine simple slopes, variables were centered at the mean (moderate), one standard deviation above the mean (high), and one standard deviation below the mean (low).

Results

Respondent Characteristics

The mean age of participants was 53.5 years (SD = 13.1), 56.3% were women, and the mean number of smokers in the household was 1.3. At baseline, respondents perceived the combined risk of radon and smoking as between “Somewhat more” and “Twice as risky” as drinking five alcoholic beverages in one day (M = 3.26, SD = 1.79, on a 7-point scale). Women rated themselves significantly lower than men on Emotionally Stability, t(593) = 3.62, p <.001, which is a typical finding (Costa, Terracciana, & McCrae, 2001; Feingold, 1994). Women rated themselves significantly higher than men on Conscientiousness, t(589) = 2.13, p <.05. When gender differences are observed on Conscientiousness, they are typically small and in this direction (Costa et al., 2001). There were no gender differences on Extraversion, or on perceptions of the combined risk of radon and smoking. Comparisons of the means (and standard deviations) of each trait for this sample with those obtained on the same measures for an equivalent Oregon community sample (N = 693) indicated that the present sample was less extraverted, 3.1 (.84) versus 3.3 (.82), t(1289) = 3.68, p < .001, and less emotionally stable, 3.3 (.81) versus 3.5 (.81), t(1291) = 4.16, p < .001, and was equivalent on Conscientiousness, 4.0 (.56) versus 4.0 (.61), t(1287) = 0.30, ns.

Among the sample of 380 respondents reporting no complete ban on household smoking at baseline, 134 households had no rules about smoking in the home, and 246 had a partial ban. At 12 months follow-up, 96 had no rules, 197 had a partial ban, and 87 had a complete ban, Chi square = 136.98, df = 2, p <.001. The number of cigarettes reported to be smoked in the home reduced from baseline (M = 11.10, SD = 12.64) to follow-up (M = 7.90, SD = 11.69), t(516) = 7.94, p < .001. Of the 367 smoker responders at baseline, 52 reported having quit at 12 months follow-up (14%).

Prediction of More Restrictive Household Smoking Rules

No personality traits predicted the adoption of more restrictive household smoking rules. Respondents with higher perceived risk (b = .18, OR = 1.20, 95% CI = 1.04, 1.38, p <.05), were more likely to report a more restrictive household rule at 12-months follow-up. There were no other significant effects.

Prediction of a Reduction in Cigarettes Smoked in the House

As shown in Table 1, controlling for number of cigarettes smoked at baseline, the three-way interaction of Extraversion with perceived risk and the video condition significantly predicted the number of cigarettes smoked in the home at 12 months. Further analysis of this interaction showed that perceived risk was significant for respondents in the video condition with high (b = −1.65, t(516) = −3.77, p <.001) and moderate levels of Extraversion (b = −.62, t(516) = −1.99, p <.05) but not for those with low levels (b = .41, t(516) = 0.96, ns). Also, as shown in Table 1, respondents in the telephone counseling condition were more likely to report a decrease in the number of cigarettes smoked in the house than those in the no counseling condition.

Table 1.

Predicting a Reduction in the Number of Cigarettes Smoked Inside the Home from Perceived Risk and Personality Traits

| Prediction variable | b | t |

|---|---|---|

| Cigarettes smoked inside at baseline | .67 | 23.69*** |

| Age | .01 | .38 |

| Gender | − .09 | − .12 |

| Education | .14 | .40 |

| Telephone counseling intervention | −2.13 | −3.02* |

| Video intervention | −.80 | −1.13 |

| Perceived risk | −.62 | −1.99* |

| Extraversion | −.42 | −.72 |

| Perceived risk × Extraversion | −1.21 | −3.43*** |

| Perceived risk × Video intervention | −.03 | − .06 |

| Video intervention × Extraversion | 1.14 | 1.35 |

| Video intervention × Extraversion × Perceived risk | 1.41 | 2.66** |

Note. For purposes of interpreting the interaction, the video intervention was coded video = 0 and no video = 1, and Extraversion and Perceived risk were centered at the mean.

p <.05,

p <.01,

p<.001.

Prediction of Quitting

Table 2 summarizes the final model. As shown, the three-way interaction of gender, with perceived risk and Conscientiousness significantly predicted quitting. Further analysis of this interaction showed that for women who were high (b = .46, OR = 1.59, 95% CI = 1.06, 2.39, p <.05) or moderate (b = .31, OR = 1.37, 95% CI = 1.01, 1.85, p <.05) on Conscientiousness, perceived risk predicted quitting, but perceived risk did not predict quitting for women low on Conscientiousness (b = .16, OR = 1.18, 95% CI = .73, 1.90, ns). However, for men, perceived risk did not predict quitting for those with high (b = −.19, OR = .82, 95% CI = .83, 1.78, ns) or moderate (b = .15, OR = 1.16, 95% CI = .84, 1.61, ns) levels of Conscientiousness, but did predict for men with low levels of Conscientiousness, (b = .50, OR = 1.64, 95% CI = 1.02, 2.64, p < .05).

Table 2.

Predicting Quitting Smoking from Perceived Risk and Personality Traits

| Prediction variable | b | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −.00 | .99 | .97, 1.03 |

| Gender | − .03 | .97 | .50, 2.10 |

| Education | .12 | 1.12 | .83, 1.51 |

| Perceived risk | .15 | 1.16 | .84, 1.61 |

| Conscientiousness | .34 | 1.41 | .58, 3.40 |

| Gender by Conscientiousness | .07 | 1.07 | .31, 3.68 |

| Perceived risk by Conscientiousness | −.59* | .55 | 1.10, 2.96 |

| Gender by Perceived risk | .16 | 1 .17 | .76, 1.82 |

| Gender by Perceived risk by Conscientiousness | .85* | 2.35 | 1.11, 4.96 |

Note. For purposes of interpreting the interaction, gender was coded male = 0, female = 1, and Conscientiousness and Perceived risk were centered at the mean. OR = Odds Ratio, CI = Confidence Interval.

p<.05,

p<.01.

Discussion

This study evaluated the influence of individuals’ personality traits and risk perceptions on the effect of interventions on both household and individual smoking outcomes. The main findings were that the traits of Extraversion and Conscientiousness had moderating effects on changes in smoking behaviors, and risk perceptions were involved in the prediction of all three outcomes. Higher perceived risk predicted change on smoking behaviors, either as a main effect (more restrictive household rules) or when moderated by other factors (reduction in cigarettes smoked indoors and quitting), which is consistent with models of risk reduction (e.g., Connor & Norman, 1996; Weinstein & Sandman, 1992).

For those in the video condition with high and moderate levels of Extraversion, perceived risk predicted a reduction in cigarettes smoked in the home. The video intervention provided role models for successful social influence by depicting a family discussing the results of their radon test, and deciding to ban smoking in their home and encouraging the smokers to quit or to smoke outside. Individuals who were more extraverted appear to have benefited from the modeling of social influence strategies. A moderating effect of Extraversion was not observed on household smoking rules, perhaps because it is easier to persuade one or more individuals to reduce their indoor smoking than to get everyone to agree to a more restrictive smoking ban. Moreover, those with higher risk perceptions were more likely to report more restrictive household smoking rules, and this effect was not moderated by personality traits, suggesting that for this outcome there was no additional benefit for those with higher levels on the traits measured in this study.

In our previous study, Conscientiousness was unrelated to quitting but did predict household-level smoking outcomes (Hampson et al., 2000). In the present study, Conscientiousness did not predict household level outcomes (smoking rules or number of cigarettes smoked in the house) but it did exert a moderating effect on predictors of quitting. Consistent with hypothesized effects for Conscientiousness, greater perceived risk predicted quitting for more conscientious women. However, for men, greater perceived risk predicted quitting only for those relatively low in Conscientiousness. This finding for men is not readily interpretable but may provide further indication that there are gender differences in the biological and social processes underlying the maintenance of smoking (e.g., Bohadana, Nilsson, Rasmussen, & Martinet, 2003; Perkins, 2001).

In the present study, contrary to hypothesis, Conscientiousness did not moderate the effectiveness of the interventions. For the subsamples analyzed here, there was a main effect of telephone counseling on reduction of cigarettes smoked indoors that was not moderated by other factors. The video condition predicted a reduction in number of cigarettes smoked indoors when moderated by perceived risk and Extraversion. It is possible that interventions that make greater demands on participants’ conscientiousness traits than receiving one or two phone calls or watching a short video would reveal a moderating effect of this personality dimension. Consistent with this hypothesis, Conscientiousness was significantly correlated with reports of how much of the video was watched (r = .14, p <.05), whereas Extraversion (r = .08) and Emotional Stability (r = .08) were not.

This study had a number of limitations. Only three of the broad traits in the five-factor model were investigated. This was regrettable because hostility (low Agreeableness) has a well-established association with smoking (e.g., Gilbert, 1995), and Openness subsumes some features of sensation seeking (Roberti, 2004), and therefore may also be associated with smoking. Furthermore, the brief measure of the five-factor personality model did not assess the specific traits subsumed by each of the broad traits. The broad traits only assess the variance common to these more narrow traits so the influence of their specific variance was not explored. In future studies, a more extensive measure of personality is recommended. Smoking outcomes were assessed by the respondents’ reports on their own behavior and on members of their household using a measure of household smoking that had been were previously biochemically validated in a dosimeter study (Glasgow et al., 1998). However, concurrent biochemical validation may be warranted in future studies of changes in household smoking patterns.

In sum, despite the absence of a number of expected findings, several illuminating influences of personality traits and risk perceptions were observed. In particular, these findings demonstrated that personality traits moderated other influences (i.e., intervention condition and perceived risk) on changes on two smoking-related outcomes. These findings add to research suggesting that more effective interventions may be achieved by tailoring content or targeting certain groups based on individual differences.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Cancer Institute Grant R01-CA68186. We thank Shawn Boles and Marta Makarushka for assistance with data analysis, and Elizabeth Mondulick for help with manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

96% of households had test results under 4 pCi/L, the action level advocated by EPA but even these low levels of radon, in combination with smoking, constitute a health threat.

In preliminary analyses, the stability of risk perceptions over the three assessments was investigated with mixed model analyses of variance using the perceived risk of the combined versus single hazards and time as within factors and the two intervention conditions as between factors. In the first analysis, the perceived risk of radon was compared to the perceive risk of the combination of radon and smoking, and in the second analysis the perceived risk of smoking was compared to the combined risk. These analyses showed no significant changes in risk perceptions over time and no effect of either intervention condition on either the perceived combined risk or the perceived single risk. The combined risk was rated significantly higher than the risk of each the separate hazards at each of the assessments: combined risk vs. radon, F(1, 575) = 1697.1, p <.001; combined risk vs. smoking, F(1,618) = 204.62, p <.001. Accordingly, the combined risk at baseline was the measure of risk perceptions used in the subsequent analyses.

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at http://www.apa.org/journals/hea/

Contributor Information

Sarah E. Hampson, Department of Psychology, University of Surrey and Oregon Research Institute

Judy A. Andrews, Oregon Research Institute

Maureen Barckley, Oregon Research Institute.

Edward Lichtenstein, Oregon Research Institute.

Michael E. Lee, Oregon Research Institute

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bogg T, Roberts BW. Conscientiousness and health-related behaviors: A meta-analysis of the leading behavioral contributors to mortality. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130:887–919. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.6.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohadana A, Nilsson F, Rasmussen T, Martinet Y. Gender differences in quit rates following smoking cessation with combination nicotine therapy: Influence of baseline smoking behavior. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2003;5:111–116. doi: 10.1080/1462220021000060482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss DM. Manipulation in close relationships: Five personality factors in interactional context. Journal of Personality. 1992;60:477–499. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell DF, Burger JM. Personality and social influence strategies in the workplace. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1997;23:1003–1012. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation for the behavioral sciences. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Conner M, Norman P, editors. Predicting health behavior: Research and practice with social cognition models. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Health Risks of Exposure to Radon. Health effects of exposure to radon: BIER IV. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr, Terracciana A, McCrae RR. Gender differences in personality traits across cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;81:322–331. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.81.2.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Digman JM. Personality structure: Emergence of the five-factor model. In: Porter LW, Rosenzweig MR, editors. Annual Review of Psychology. Vol. 41. 1990. pp. 417–440. [Google Scholar]

- Environmental Protection Agency. Technical support document for the 1992 Citizen’s Guide to Radon (EPA publication No. 400-R-92-011) Washington, DC: Author; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Feingold A. Gender differences in personality. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:429–456. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman HS, Tucker JS, Schwartz JE, Martin LR, Tomlinson-Keasy C, Wingard DL, Criqui MH. Childhood conscientiousness and longevity: Health behaviors and cause of death. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;68:696–703. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.68.4.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DG. Smoking: Individual differences, psychopathology, and emotion. Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE, Boles SM, Lichtenstein E, Lee ME, Foster L. Adoption, reach, and implementation of a novel smoking control program: Analysis of a public utility-research organization partnership. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2004;6:269–274. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001676404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE, Foster LS, Lee ME, Hammond SK, Lichtenstein E, Andrews JA. Developing a brief measure of smoking in the home: description and preliminary evaluation. Addictive Behaviors. 1998;23:567–571. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR. The structure of phenotypic personality traits. American Psychologist. 1993;48:26–34. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA. A critique of Eysenck’s theory of personality. In: Eysenck HJ, editor. A model for personality. New York: Springer; 1981. pp. 246–276. [Google Scholar]

- Hampson SE, Andrews JA, Barckely M, Lee ME, Lichtenstein E. Assessing perceptions of synergistic health risk: A comparison of two scales. Risk Analysis. 2003;23:1021–1029. doi: 10.1111/1539-6924.00378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson SE, Andrews JA, Barckely M, Lichtenstein E, Lee ME. Conscientiousness, perceived risk, and risk-reduction behaviors: A preliminary study. Health Psychology. 2000;19:496–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgason AR, Fredrikson M, Dyba T, Steineck G. Introverts give up smoking more often than extraverts. Personality and Individual Differences. 1995;18:559–560. [Google Scholar]

- John OP, Srivastava S. The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In: Pervin LA, John OP, editors. Handbook of personality theory and research. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 139–153. [Google Scholar]

- John OP, Donahue EM, Kentle RL. The “Big Five” Inventory--Versions 41 and 5a. University of California, Berkeley: Institute of Personality and Social Research; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph S, Manafi E, Iakovaki AM, Cooper R. Personality, smoking motivation, and self-efficacy to quit. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003;34:749–758. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein E, Andrews JA, Lee ME, Glasgow RE, Hampson SE. Using radon risk to motivate smoking reduction: evaluation of written materials and brief telephone counseling. Tobacco Control. 2000;9:320–326. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.3.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein E, Lee ME, Boles SM, Hampson SE, Glasgow RE. Using radon risk to motivate smoking reduction II: Evaluation of brief telephone counseling and a targeted video. doi: 10.1093/her/cym016. Manuscript in preparation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McChargue DE, Cohen LM, Cook JW. The influence of personality and affect on nicotine dependence among male college students. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2004;6:287–294. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001676323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ockene JK, Emmons KM, Mermelstein RJ, Perkins KA, Bonollo DS, Voorhees CC, Hollis JF. Relapse and maintenance issues for smoking cessation. Health Psychology. 2000;19(1 Suppl):17–31. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.suppl1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA. Smoking cessation in women: Special considerations. CNS Drugs. 2001;15:391–411. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200115050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reif A, Heeran T. Consensus on synergism between cigarette smoke and other environmental carcinogens in the causation of lung cancer. Advances in Cancer Research. 1999;76:161–186. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60776-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberti JW. A review of behavioral and biological correlates of sensation seeking. Journal of Research in Personality. 2004;38:256–279. [Google Scholar]

- Slovic P. Perceptions of risk: Reflections on the psychometric paradigm. In: Krimsky S, Golding D, editors. Social theories of risk. Westport, CT: Praeger; 1992. pp. 117–152. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein ND, Sandman PM. A model of the precaution adoption process: evidence from home radon testing. Health Psychology. 1992;11:170–180. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.11.3.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams-Piehota P, Pizarro J, Schneider TR, Mowad L, Salovey P. Matching health messages to monitor-blunter coping styles to motivate screening mammography. Health Psychology. 24:58–67. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]