Abstract

Magnetic resonance electrical impedance tomography (MREIT) has the potential to provide conductivity and current density images with high spatial resolution and accuracy. Recent experimental studies at a field strength of 3 T showed that the spatial resolution of conductivity and current density images may be similar to that of conventional MR images as long as enough current is injected, at least 20 mA when the object being imaged has a size similar to the human head. To apply the MREIT technique to image small conductivity changes using less injection current, we performed MREIT studies at 11 T field strength, where noise levels in measured magnetic flux density data are significantly lower. In this paper we present the experimental results of imaging biological tissues with different conductivity values using MREIT at 11 T. We describe technical difficulties encountered in using high-field MREIT systems and possible solutions. High-field MREIT is suggested as a research tool for obtaining accurate conductivity data from tissue samples and animal subjects.

Keywords: MREIT, conductivity, high magnetic field

1. Introduction

Magnetic resonance electrical impedance tomography (MREIT) is a potentially high-resolution conductivity imaging method (Zhang 1992, Woo et al 1994, 2005, Ider and Birgul 1998, Joy 2004). It proceeds from MRI measurements of internal magnetic flux densities caused by externally applied currents (Scott et al 1991, 1992). Experimental MREIT studies at 3 T field strength showed that the spatial resolution of both conductivity and current density images is comparable to that of MR magnitude images created from the same data set if enough current is injected. For example, an object having the size of the human head can be imaged at MRI resolution if a current of 20–40 mA is applied (Oh et al 2003, 2004, 2005).

When injecting current into tissue through pairs of surface electrodes, local conductivity changes caused by, for example, neural activity or pathological changes in the tissue will distort the original internal current density distributions (Holder 2005). When current flows, a magnetic flux density distribution is formed following the Biot–Savart law. These conductivity changes will alter the magnetic flux density distribution (Lee et al 2003a). In order to detect small conductivity changes from measured magnetic flux density data, it is essential to minimize noise in the measured data.

In this paper, we present results of MREIT studies performed at a field strength of 11 T. Our primary reason for using such a high-field MRI scanner was to reduce noise levels in measured magnetic flux density data. The benefits in terms of conductivity imaging include higher accuracy and sensitivity to small conductivity changes. It is also possible to reduce the injection current magnitude at this field level, allowing consideration of high resolution imaging of conductivity changes in living tissue. In developing experimental MREIT techniques at high-field strength, we intend to establish the feasibility of MREIT as a research tool to quantify physiological and pathological conductivity changes as well as the static conductivities of tissues and organs. For example, we may use this technique to image small conductivity changes produced by neural stimulation in neural tissue phantoms and small animals. Postmortem animal imaging may provide accurate conductivity values that could be used to improve solution quality in biomedical research areas such as EEG/MEG and ECG/MCG source imaging (Gao et al 2005).

As the first step toward these goals, Sadleir et al (2005a) examined noise levels in measured magnetic flux density using two MREIT systems at 3 and 11 T field strengths. They found that typical noise levels were about 0.25 and 0.05 nT at 3 and 11 T, respectively, at a voxel size of 3 × 3 × 3 mm3. These results suggested that conductivity images from an 11 T MREIT system should have better sensitivity and accuracy than at 3 T.

Using a homogeneous conductivity phantom and the 11 T MRI scanner, Sadleir et al (2005b) reconstructed the first 11 T MREIT images, demonstrating superior image quality compared with images at 3 T. However, they only showed homogeneous conductivity images since performing MREIT imaging experiments at 11 T involves particular technical challenges, and more carefully designed experimental methods were indicated to successfully image tissues. In this paper we explain how we addressed some of these problems to successfully set up the 11 T MREIT system. We present 11 T MREIT images of biological tissue phantoms and suggest further use of high-field MREIT studies as a valuable research tool for obtaining high-resolution conductivity and current density images.

2. Methods

2.1. Conductivity image reconstruction in MREIT

To successfully reconstruct isotropic MREIT conductivity images, we sequentially inject currents into an object through at least two pairs of surface electrodes. Each injection current produces voltage, current density and magnetic flux density distributions inside the object. These are determined by the unknown conductivity distribution as well as the known electrode configuration and shape of the object. Using an MRI scanner, we measure one component Bz of the induced internal magnetic flux density B = (Bx, By, Bz). The image reconstruction problem in MREIT is to find the conductivity distribution from measured Bz data subject to these multiple injection currents (Seo et al 2003, 2004, Oh et al 2003, Park et al 2004a, 2004b, Ider and Onart 2004, Woo et al 2005). In this paper, we used the harmonic Bz algorithm developed by Seo et al (2003) and experimentally validated by Oh et al (2003, 2004, 2005).

2.2. 11 T MREIT setup and conductivity phantoms

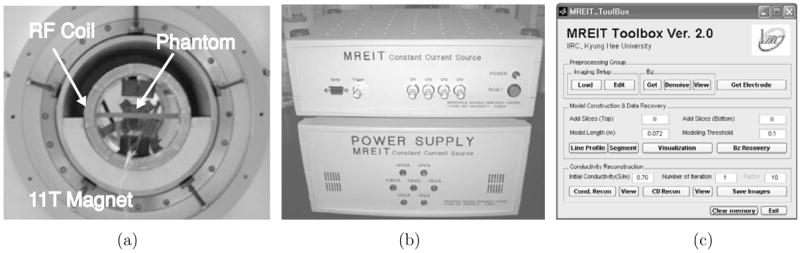

We used the 11 T MRI scanner (Bruker Biospin, MA, USA) in the McKnight Brain Institute at the University of Florida, USA. It has a 400 mm bore suitable for tissue preparations and small animals. Figure 1(a) shows a view of the 11 T super-conducting magnet with an RF coil and a phantom placed inside the bore. We used the custom-designed MREIT current source shown in figure 1(b) to apply currents to the phantom. The data processing and conductivity image reconstructions were performed using the Matlab-based MREIT Toolbox software, a screenshot from which is shown in figure 1(c) (Kim et al 2005).

Figure 1.

11 T MREIT system setup: (a) 11 T super-conducting magnet with an RF coil and a phantom, (b) current source and (c) data processing and image reconstruction software.

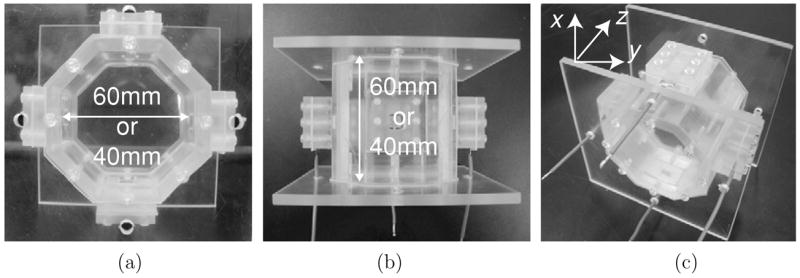

We prepared imaging phantoms constructed of acrylic plastic. They typically contained saline, agar or animal hide gelatine with incorporated biological tissues. Figure 2 shows a conductivity phantom having both diameter and height of either 60 mm or 40 mm. In this paper, we refer to these phantoms as either the ‘60 mm phantom’ or ‘40 mm phantom’. Recessed electrode assemblies, through which current was injected into the phantom, were attached on four sides of the octagonal column. By using recessed electrodes we avoided RF shielding problems and consequent Bz artifacts caused by having metal electrodes directly in contact with the object surface (Lee et al 2003b, Oh et al 2003). The sizes of each recessed electrode assembly were 7.55 × 7.55 × 10 and 6 × 6 × 10 mm3 for the ‘60 mm phantom’ and ‘40 mm phantom’, respectively. The copper electrodes each had a size of 5 × 7.55 or 5 × 6 mm2, respectively.

Figure 2.

Phantom design: (a) front view, (b) top view and (c) oblique view. The z-direction denotes the orientation of the main magnetic field B0.

2.3. MREIT experiments

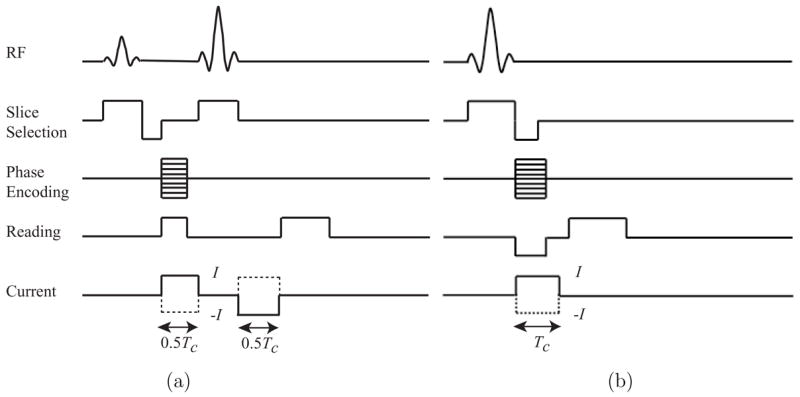

After one of the phantoms was placed inside the 11 T machine, we injected a current I1 between an opposing pair of electrodes, synchronous with the MRI pulse sequence. The pulse sequences shown in figure 3 were used with either of two multi-slice imaging techniques (Scott et al 1991): the spin echo (SE) pulse sequence shown in figure 3(a) or the gradient echo (GE) pulse sequences shown in figure 3(b). The injection current magnitude I was chosen at levels between 5 and 20 mA, with a pulse width Tc between 9 and 18 ms depending on the chosen echo time (TE). The slice thicknesses used were 1 or 2 mm, with no slice gap. Data from eight axial slices were gathered in each scan, therefore the total region imaged spanned a region with thickness between 8 and 16 mm, centered on the electrode plane. After acquiring eight slices for I1, denoted as , another current I2, with the same magnitude as I1, was injected through the other pair of electrodes to obtain the image set. The image matrix size used in each case was 128 × 128. The field-of-view (FOV) was between 80 × 80 and 128 × 128 mm2, therefore the pixel size was between 0.625 × 0.625 and 1 × 1 mm2.

Figure 3.

MREIT pulse sequences: (a) spin echo (SE) and (b) gradient echo (GE) pulse sequences with synchronized injection current pulses (Scott et al 1991). The positive and negative current pulses with an amplitude of I and width of Tc are shown as the solid and dotted lines, respectively.

3. Results

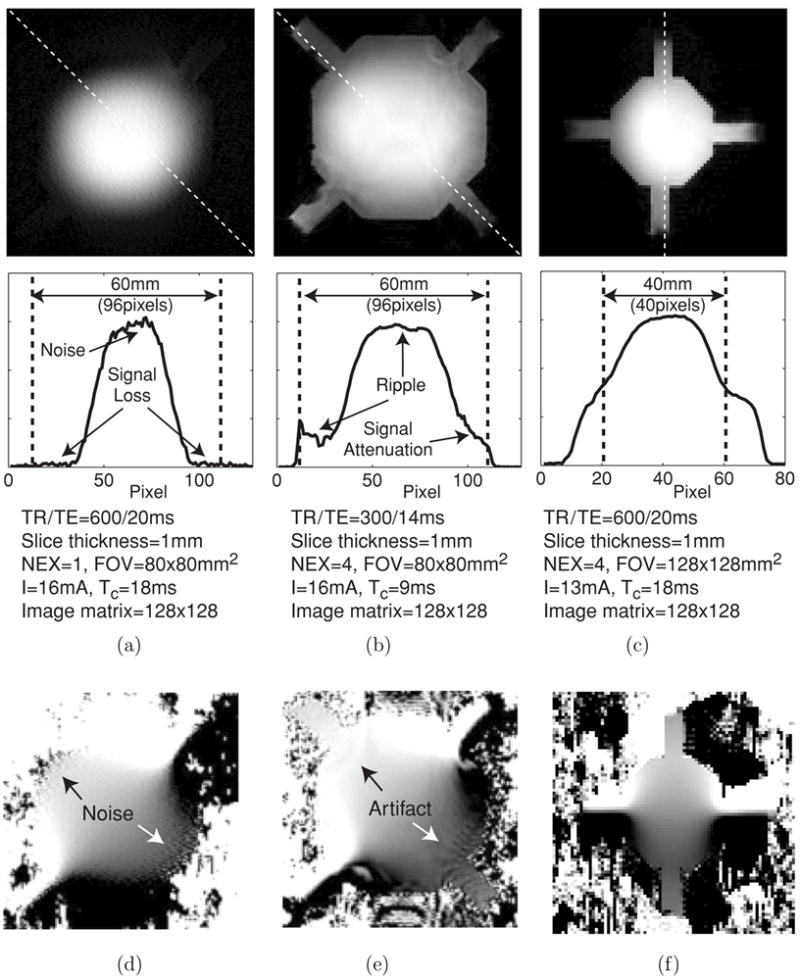

Figure 4 shows experimental results using phantoms filled with homogeneous saline. Figures 4(a) and (b) are MR magnitude images and the one-dimensional profiles of the 60 mm phantom using SE and GE pulse sequences, respectively. Figure 4(c) is the magnitude image and profile of the 40 mm phantom using the SE pulse sequence. For better comparison, we normalized the images in figures 4(a), (b) and (c) so that the maximal pixel value in each image becomes 1. The signal-to-noise ratios (SNR) were estimated as 76, 151 and 182 in the central region of figures 4(a), (b) and (c), respectively. Figures 4(d), (e) and (f) show magnetic flux density ( ) images corresponding to magnitude images in (a), (b) and (c), respectively.

Figure 4.

Effects of different pulse sequences using homogeneous saline phantoms. Normalized magnitude images and their profiles in the 60 mm phantom using (a) SE and (b) GE pulse sequence. For (a) and (b), pixel size was 0.625 × 0.625 mm2. (c) Normalized magnitude image and its profile in the 40 mm phantom using the SE pulse sequence with 1 × 1 mm2 pixel size. One-dimensional profiles are shown below corresponding to the dotted lines in magnitude images. (d) and (e) images of the 60 mm phantom corresponding to (a) and (b), respectively. (f) image of the 40 mm phantom corresponding to (c).

The images in figure 4 illustrate possible technical problems that may be encountered in high-field MREIT experiments. In figure 4(a), we observed the signal intensity gradually decreasing towards the outer boundary of the phantom. This corresponded with a gradually increasing noise level in the image, as shown in figure 4(d). Standing wave effects at the short RF wavelength of 11 T (450 MHz) are believed to cause this characteristic (Beck et al 2004). In the GE data shown in figure 4(b), we observed ripple artifacts as well as signal attenuation in the magnitude data related to the main magnetic field inhomogeneity. These appeared as similar artifacts in the corresponding image shown in figure 4(e). In order to avoid these artifacts, it was essential to shim the magnet as well as possible. It was necessary to keep the object size small, and to pay close attention to tuning imaging parameters including RF gain and bandwidth, as well as considering the appropriate settings of TR/TE and number of averages (NEX). Figures 4(c) and (f) show images of the homogeneous 40 mm phantom with much smaller noise and artifact after careful parameter adjustment.

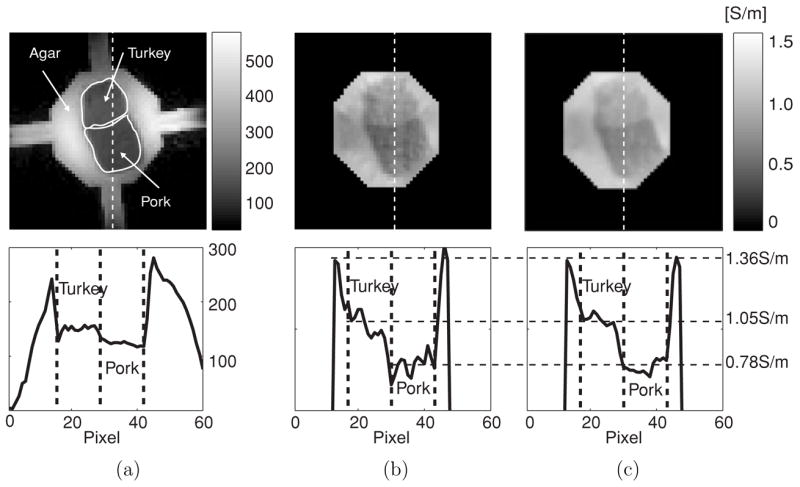

Figure 5(a) shows the MR magnitude image of a 40 mm tissue phantom. The background material was an agar gel with a conductivity of 1.4 S m−1. Inside the phantom, we placed two different muscle samples (porcine muscle and turkey breast) packed closely together. The average SNR in the magnitude image were 380, 140 and 107 inside the agar, turkey and pork, respectively. Figures 5(b) and (c) show the reconstructed conductivity images using 10 and 20 mA injection currents, respectively, with a SE pulse sequence. Average conductivity values for the pork and turkey tissues were found to be 0.78 and 1.05 S m−1, respectively. Note that the two different tissues can be distinguished in the conductivity images better than in the magnitude image.

Figure 5.

(a) MR magnitude image of a 40 mm tissue phantom containing samples of preserved porcine muscle and turkey breast. (b) and (c) are conductivity images using 10 and 20 mA injection current, respectively. We used the same scale bar for both (b) and (c). Note that the image in (b) has more noise. A SE pulse sequence was used with TR/TE = 800/20 ms and Tc = 18 ms. Number of slices (NS) was eight, NEX was 8, slice thickness was 1 mm, FOV was 128 × 128 mm2, image matrix size was 128 × 128 and pixel size was 1 × 1 mm2.

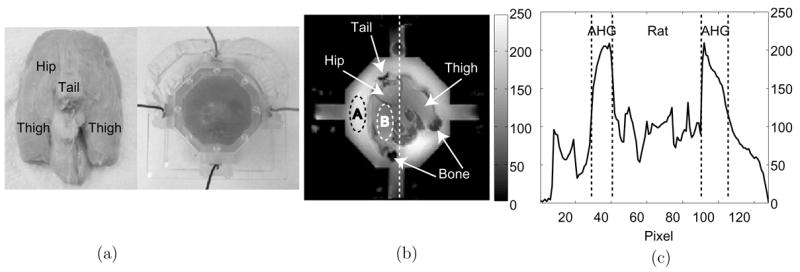

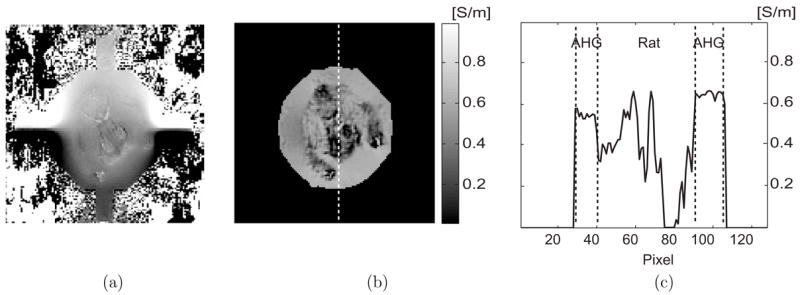

Figure 6(a) shows a 60 mm phantom containing the lower body of a rat. The phantom background was filled with an animal hide gelatine (AHG) with a conductivity of 0.6 S m−1. We used a multi-slice SE imaging method with fat suppression. Figures 6(b) and (c) are the magnitude image at the middle imaging slice and its one-dimensional profile along the dotted line, respectively. Inside the regions marked as ‘A’ and ‘B’ in figure 6(b), average SNRs were 232 and 114, respectively. Figure 7(a) is the measured magnetic flux density image of at the same imaging slice using 18 mA injection current. Figures 7(b) and (c) are the reconstructed conductivity image and its profile along the same dotted line marked in figure 6(b), respectively.

Figure 6.

(a) 60 mm phantom containing the lower body of a rat. The background was filled with an animal hide gelatine (AHG) at 0.6 S m−1, (b) MR magnitude image and (c) its profile along the dotted line. A SE pulse sequence was used with TR/TE = 700/10 ms, I = 18 mA and Tc = 9 ms. Eight slices were imaged with 2 mm slice thickness, NEX was 16, FOV was 100 × 100 mm2, image matrix size was 128 × 128 and pixel size was 0.78 × 0.78 mm2.

Figure 7.

(a) Measured magnetic flux density images, of the 60 mm phantom shown in figure 6. (b) and (c) are reconstructed conductivity image and its profile along the dotted line, respectively.

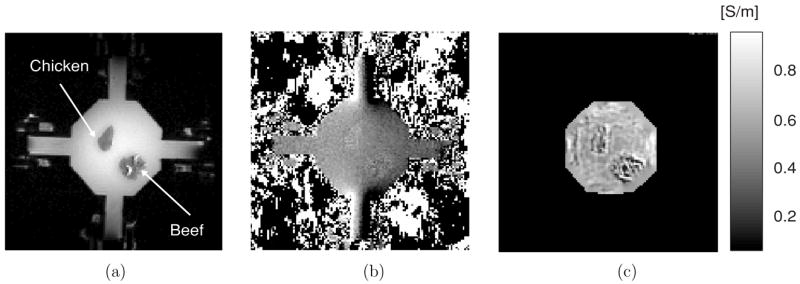

Figure 8(a) shows the MR magnitude image of a 40 mm phantom with a background conductivity of gelatin at 0.6 S m−1. Inside the phantom, we placed two small pieces of different muscle tissues (chicken breast and bovine muscle). Figures 8(b) and (c) are one magnetic flux density and the reconstructed conductivity image, respectively, using a 5 mA injection current. These images qualitatively show the effect of reducing injection current.

Figure 8.

MREIT experiment at 5 mA injection current. (a) MR magnitude image of a 40 mm tissue phantom containing pieces of chicken breast and bovine muscle. (b) Magnetic flux density image. (c) Reconstructed conductivity image. A SE pulse sequence was used with TR/TE = 600/10 ms, I = 5 mA and Tc = 9 ms. Eight slices were imaged with 1 mm slice thickness, NEX was 16, FOV was 80 × 80 mm2, image matrix size was 128 × 128 and pixel size was 0.625 × 0.625 mm2.

4. Discussion

Since MREIT relies on MR phase signals, it requires a high degree of main magnetic field homogeneity and gradient linearity. Even though the large main magnetic field of 11 T enables us to reduce intrinsic phase noise levels, we may fail to take advantage of such a high field without properly adapting low-field MREIT experiments. As illustrated in figure 4, many problems such as signal loss or attenuation and artifacts can be amended by better shimming of the magnet and tuning of imaging parameters. For most experiments described in this paper, SE pulse sequences were used as we found that SE usually produces better results with fewer artifacts compared with GE.

When imaging biological tissues, we recommend longer TR times to obtain more signal strength, at the expense of prolonged scan times. The current injection pulse width Tc should be chosen so that it is slightly shorter than TE. Thus, increasing TE allows us to choose a wider Tc to reduce noise level in magnetic flux density signals. However, using a longer TE decreases MR signal strength and leads to lower magnitude image SNR. Therefore, before commencing MREIT scanning, we recommend trying at least two different TR/TE values to evaluate noise levels and SNRs using the method described in Scott et al (1991 and 1992) and Sadleir et al (2005) to find proper values of TR/TE for a given sample configuration.

Any chosen RF coil must be tuned carefully for each subject or phantom. At high fields of 11 T and above, the long metal wires connected to electrodes have a large effect on RF coil tuning characteristics. Use of carbon fiber wires has been found to improve image quality (Sadleir et al 2005c) as long as the current source has enough voltage compliance to overcome the increased load resistance.

We found that the 11 T system produced images with much larger geometrical distortion than at 3 T, especially in the outer regions of larger objects. This distortion is believed to be due to inhomogeneity in the main magnetic field and gradient field nonlinearity. The distortion is significantly worse without correct shimming (Sadleir et al 2005b). At 11 T, standing wave effects also limit the size of imaged objects (Beck et al 2004). For these reasons, we found that even though the 11 T MRI scanner has a 400 mm bore, the useful MREIT imaging area was less than 100 mm about its central axis.

The images and profiles shown in figure 5 illustrate that MREIT images can distinguish tissues better than conventional MR images when there exist enough conductivity differences among tissues and not much contrast in conventional MR images. Compared with experimental results using 3 T published in Oh et al (2005), high-field MREIT shows a similar ability to distinguish different tissues with small conductivity contrasts, but using significantly smaller injected currents. In both figures 5(b) and (c), reconstructed conductivity images show a slightly darker area to the left of the tissue samples. We speculate that this could have been caused by artifacts along the phase encoding direction, unless the agar gel was actually inhomogeneous due to improper mixing. Further studies are needed to investigate artifacts and noise effects in reconstructed conductivity images.

When the imaged object contains a complex mixture of many different tissues, as in figure 6, it seems to be difficult to quantitatively measure or visualize the internal conductivity distribution in its absolute values using other methods such as electrical impedance tomography (EIT) (Holder 2005) or diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) (Tuch et al 2001). The image in figure 7(b) illustrates the capability of MREIT to measure the spatially varying conductivity distribution of a mixture of tissues in its absolute values. In future studies, we plan MREIT imaging of animals by attaching electrodes directly to their skin. It would also be very interesting to compare reconstructed conductivity images obtained by using different techniques including MREIT, EIT and DTI.

Figure 8 shows the first MREIT image using injection currents as low as 5 mA. Even though the image quality is low compared with the results at 10 or 20 mA, we can observe the conductivity contrast both in the magnetic flux density and reconstructed conductivity images. This shows the benefit of the high-field system compared to the 3 T results described in Oh et al (2003, 2004, 2005). One of the reasons for the noisy conductivity image inside the tissues shown in figure 8(c) could be the relatively short TR. Improvements in image quality and further reduction in injection current amplitude are being pursued in studies planned for the near future, incorporating improved pulse sequences and RF coils, better (probably hybrid) algorithms and efficient denoising techniques (Lee et al 2005). Theoretical analysis and further experimental work are also needed to find a more concrete relationship between image quality and noise level.

5. Conclusion

We present results of MREIT experiments performed at 11 T field strength. Although noise levels in the measured magnetic flux density data are smaller using the 11 T system, we found we had to resolve problems related to systematic artifacts. Amongst many factors, proper shimming of the magnet is most important. We found that the object size must be selected with reference to the system’s field uniformity and gradient linearity, and not just by the bore size.

These 11 T MREIT experiments suggest that we may reduce the injection current to 5 mA in future studies. We plan to further improve our experimental MREIT techniques at 11 T and higher field strengths. Our primary goal is to image small conductivity changes associated with physiological and pathological changes. We will undertake high-field MREIT experimental studies using neural tissue preparations and small animals in the near future.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Advanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Spectroscopy (AMRIS) facility at the McKnight Brain Institute, University of Florida, USA and grants R11-2002-103/M60501000035-05A0100-03510 from the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation (KOSEF) in Korea.

References

- Beck BL, Jenkins K, Caserta J, Padgett K, Fitzsimmons J, Blackband SJ. Observation of significant signal voids in images of large biological samples at 11.1 T. Magn Reson Med. 2004;51:1103–7. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G, Zhu SA, He B. Estimation of electrical conductivity distribution within the human head from magnetic flux density measurement. Phys Med Biol. 2005;50:2675–87. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/50/11/016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holder D, editor. Electrical Impedance Tomography: Methods, History and Applications. Bristol: Institute of Physics Publishing; 2005 . [Google Scholar]

- Ider YZ, Birgul O. Use of the magnetic field generated by the internal distribution of injected currents for electrical impedance tomography (MR-EIT) Elektrik. 1998;6:215–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ider YZ, Onart S. Algebraic reconstruction for 3D MR-EIT using one component of magnetic flux density. Physiol Meas. 2004;25:281–94. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/25/1/032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joy ML. MR current density and conductivity imaging: the state of the art. Proc. 26th Ann. Int. Conf. IEEE EMBS; San Francisco CA, USA. 2004. pp. 5315–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TS, Lee BI, Park C, Lee SH, Tak SH, Seo JK, Kwon O, Woo EJ. A Matlab toolbox for magnetic resonance electrical impedance tomography (MREIT): MREIT toolbox. Int J Bioelectromagn. 2005;7:352–5. [Google Scholar]

- Lee BI, Oh SH, Woo EJ, Lee SY, Cho MH, Kwon O, Seo JK, Lee JY, Baek WS. Three-dimensional forward solver and its performance analysis in magnetic resonance electrical impedance tomography (MREIT) using recessed electrodes. Phys Med Biol. 2003a;48:1971–86. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/48/13/309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BI, Oh SH, Woo EJ, Lee SY, Cho MH, Kwon O, Seo JK, Baek WS. Static resistivity image of a cubic saline phantom in magnetic resonance electrical impedance tomography (MREIT) Physiol Meas. 2003b;24:579–89. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/24/2/367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BI, Lee SH, Kim TS, Kwon O, Woo EJ, Seo JK. Harmonic decomposition in PDE-based denoising technique for magnetic resonance electrical impedance tomography. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2005;52:1912–20. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2005.856258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh SH, Lee BI, Woo EJ, Lee SY, Cho MH, Kwon O, Seo JK. Conductivity and current density image reconstruction using harmonic Bz algorithm in magnetic resonance electrical impedance tomography. Phys Med Biol. 2003;48:3101–16. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/48/19/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh SH, Lee BI, Park TS, Lee SY, Woo EJ, Cho MH, Kwon O, Seo JK. Magnetic resonance electrical impedance tomography at 3 tesla field strength. Mag Reson Med. 2004;51:1292–6. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh SH, Lee BI, Woo EJ, Lee SY, Kim TS, Kwon O, Seo JK. Electrical conductivity images of biological tissue phantoms in MREIT. Physiol Meas. 2005;26:S279–88. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/26/2/026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C, Park EJ, Woo EJ, Kwon O, Seo JK. Static conductivity imaging using variational gradient Bz algorithm in magnetic resonance electrical impedance tomography. Physiol Meas. 2004a;25:257–69. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/25/1/030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C, Kwon O, Woo EJ, Seo JK. Electrical conductivity imaging using gradient Bz decomposition algorithm in magnetic resonance electrical impedance tomography (MREIT) IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2004b;23:388–94. doi: 10.1109/tmi.2004.824228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadleir R, et al. Noise analysis in MREIT at 3 and 11 tesla field strength. Physiol Meas. 2005a;26:875–84. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/26/5/023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadleir RJ, Grant S, Silver X, Zhang SU, Woo EJ, Lee SY, Kim TS, Oh SH, Lee BI, Seo JK. Magnetic resonance electrical impedance tomography (MREIT) at 11 tesla field strength: preliminary experimental study. Int J Bioelectromagn. 2005b;7:340–3. [Google Scholar]

- Sadleir RJ, Grant S, DeMarse TB, Woo EJ, Lee SY, Kim TS, Oh SH, Lee BI, Seo JK. MRI/MEA compatibility at 17.6 tesla. Int J Bioelectromagn. 2005c;7:278–81. [Google Scholar]

- Scott GC, Joy MLG, Armstrong RL, Henkelman RM. Measurement of nonuniform current density by magnetic resonance. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1991;10:362–74. doi: 10.1109/42.97586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott GC, Joy MLG, Armstrong RL, Hankelman RM. Sensitivity of magnetic resonance current density imaging. J Magn Reson. 1992;97:235–54. [Google Scholar]

- Seo JK, Yoon JR, Woo EJ, Kwon O. Reconstruction of conductivity and current density images using only one component of magnetic field measurements. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2003;50:1121–4. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2003.816080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo JK, Pyo HC, Park CJ, Kwon O, Woo EJ. Image reconstruction of anisotropic conductivity tensor distribution in MREIT: computer simulation study. Phys Med Biol. 2004;49:4371–82. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/49/18/012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuch DS, Wedeen VJ, Dale AM, George JS, Belliveau JW. Conductivity tensor mapping of the human brain using diffusion tensor MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98:11697–701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171473898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo EJ, Lee SY, Mun CW. Impedance tomography using internal current density distribution measured by nuclear magnetic resonance. Proc SPIE Ann Conf. 1994;2299:377–85. [Google Scholar]

- Woo EJ, Seo JK, Lee SY. Magnetic resonance electrical impedance tomography (MREIT) In: Holder D, editor. Electrical Impedance Tomography: Methods, History and Applications. Bristol: Institute of Physics Publishing; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N. MS Thesis. Department of Elec. Eng., University of Toronto; Toronto, Canada: 1992. Electrical impedance tomography based on current density imaging. [Google Scholar]