Abstract

This study reports findings on a combined family and school-based competency-training intervention from an in-school assessment 2.5 years past baseline, as a follow-up to an earlier study of substance initiation. Increased rates of observed alcohol use and an additional wave of data allowed evaluation of regular alcohol use and weekly drunkenness, with both point-in-time and growth curve analyses. Thirty-six rural schools were randomly assigned to (a) a combined family and school intervention condition, (b) a school-only condition, or (c) a control condition. The earlier significant outcome on a substance initiation index was replicated, and positive point-in-time results for weekly drunkenness were observed, but there were no statistically significant outcomes for regular alcohol use. Discussion focuses on factors relevant to the mix of significant longitudinal results within a consistent general pattern of positive intervention–control differences.

Keywords: universal prevention, family, school, substance use

Results of recent national surveys of lifetime alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use among young and older adolescents reveal high prevalence rates, despite trends toward reduced rates in recent years (Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration, 2002). For example, lifetime prevalence rates of alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use among 12th graders in 2003 were 77%, 54%, and 46%, respectively (Monitoring the Future, n.d.). Of considerable concern are the rates of more problematic types of use. In 2003, for instance, 31% of 12th graders surveyed reported that they had been drunk in the past 30 days. Among 10th graders, 18% reported the same (Monitoring the Future, n.d.).

Research on consequences of adolescent substance use clarifies the reasons that the magnitude of alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use is critically important to address. Additional research on causes of use suggest what might be done to reduce the levels of use. As concerns consequences, initiation and use of alcohol and other substances predict substance-related problems in later adolescence and adulthood (Kandel & Yamaguchi, 1993; Robins & Przybeck, 1985). In addition, early initiation and use have been associated with a range of other problems, including risky sexual practices and impaired mental health functioning (e.g., Duncan, Strycker, & Duncan, 1999; Windle & Windle, 2001). They also have been associated with compromised educational and occupational attainment (e.g., Kaestner, 1991) and generally lower levels of competent adult behavior (e.g., Ackerman, Zuroff, & Moskowitz, 2000). A very noteworthy aspect of alcohol-related problems among adults is the societal cost of the problems, including lost productivity, increased crime, and health care expenditures (Harwood, Fountain, & Livermore, 1998; Spoth, Guyll, & Day, 2002).

Etiological research on factors associated with young adolescent substance use highlights the important role of the family and school socializing environments. An array of risk and protective factors originating in these environments can exert considerable influence on patterns of young adolescent use (Hawkins, Catalano, & Miller, 1992; Resnick et al., 1997). Universal interventions with designs that are carefully guided by sound etiological research and developmentally well timed can positively influence these family and school socializing environments to delay initiation and regular use of substances (Mrazek & Haggerty, 1994; Spoth & Greenberg, 2005; Spoth, Redmond, & Shin, 2001). It is important to note that diffusion of evidence-based universal family and school preventive interventions—particularly those combined to enhance overall effects—could potentially contribute to the reduction of costly public health and social problems associated with youth substance use (Biglan & Metzler, 1999; Jamieson & Romer, 2002).

This study extends an earlier report on the effects of a multi-component, universal intervention combining family and school programs (Spoth, Redmond, Trudeau, & Shin, 2002). The earlier report presented in-school assessment results of a randomized, controlled study of two theory-based interventions showing positive outcomes in earlier prevention trials. The two interventions were the Iowa Strengthening Families Program (Spoth et al., 2001; Spoth, Redmond, Shin, & Azevedo, 2004), since revised and called the Strengthening Families Program: For Parents and Youth 10–14 (SFP 10–14), and Life Skills Training (LST; Botvin, Baker, Dusenbury, Botvin, & Diaz, 1995). The earlier report noted that the two evidence-based interventions address a broad range of empirically supported etiological factors (family-, peer-, and school-related) and that their universal design offers significant advantages in potentially encompassing a greater proportion of individuals likely to become disordered as adults than would interventions with clinical subpopulations (also see Jamieson & Romer, 2002). Related to this point, recent epidemiological research suggests that there is a developmental window of opportunity to intervene with general population adolescents after initial substance exposure that, if appropriately used, could accrue substantial public health benefits (Anthony, 2003).

Results from the earlier study showed significant effects in reduced substance initiation for both a combined LST + SFP 10–14 condition and an LST-only condition at a 1- year follow-up, as measured by an index of lifetime use of alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana from an in-school assessment. Relative reduction of alcohol initiation was 30% for the combined intervention (Spoth, Redmond, et al., 2002). The present study extends the earlier work in a number of important ways. First, an additional wave of data collection 2.5 years following baseline allows for the evaluation of intervention effects on substance use trajectories, via multilevel growth curve analyses.

A second extension of earlier work is made possible by increases from baseline in observed rates of usual or regular use (at least once a month) and more problematic types of alcohol use (e.g., drunkenness). This study replicates the in-school substance initiation assessment of the earlier study at a subsequent follow-up, with a focus on alcohol use, adding measures of more regular and problematic use. Because delay of substance initiation is a primary objective of the universal interventions evaluated through the program of research of which this study is a part, it has been the primary focus of a number of reports. Also, earlier reports of preventive intervention outcomes with adolescents in the same grade as those in this study have prominently featured alcohol-related outcomes, for two reasons. First, it is well established that alcohol is the drug of choice among youth. Second, because the young adolescent rates of alcohol use are the highest among the substances reported and because they progress more rapidly across the adolescent years, assessment of more problematic levels and types of use are possible as early as the age of the students in this study (see Botvin, Griffin, Diaz, & Ifill-Williams, 2001, for discussion of the developmental progression of initiation to more regular or problematic types of use).

The prospect of examining more problematic types of alcohol use prompted a review of the literature on the measurement of these types of use and guided decisions about the measurement foci of the present report. Many researchers are currently raising issues about the measurement of more problematic types of use (Carey, 2001; Lange & Voas, 2001; Thombs, Olds, & Snyder, 2003). Instead of applying the typical binge drinking measure (five drinks or more per occasion), a number of these researchers have suggested frequency of drunkenness as an alternative measure of more problematic alcohol use. For this reason, we considered it important to assess problematic alcohol use, as measured by self-report of weekly drunkenness (also see Bailey, 1999; Midanik, 1999), in addition to implementing a commonly applied measure of regular use.

On the basis of a review of the literature and outcomes from the first follow-up assessment, we hypothesized that (a) the combined universal family and school preventive intervention, consisting of LST + SPF 10–14, would result in lower levels of long-term initiation of substance use, regular alcohol use, and problematic drinking relative to a control condition; (b) the LST-only intervention also would result in lower levels of use compared with the control condition; and (c) the multicomponent intervention (LST + SPF 10–14) would show stronger effects than the LST-only condition.

Method

Recruited Schools and Individual Participants

Participants in the study were seventh graders enrolled in 36 rural schools in 22 contiguous counties in a midwestern state. The 36 schools were recruited from a pool of 43 randomly selected schools in the region. Criteria for selection of the initial pool of schools were as follows: eligibility for the free and reduced-cost school lunch program (approximately 20% or more of households in the school districts within 185% of the federal poverty level), school district enrollment under 1,200, and all middle school grades (Grades 6–8) taught at only one location. Schools did not know the experimental condition to which they had been assigned at the time they were recruited into the study.

A randomized block design guided the assignment of the 36 schools to the three experimental conditions. Schools were randomly assigned to the classroom-based LST + SFP 10–14, delivered to families of seventh graders on weekday evenings; the LST only; or a minimal contact control condition entailing mailed leaflets on teen development. The 36 schools were first split into 12 matched sets of 3 schools prior to assignment. Variables considered in the matching procedure (in order of priority) were as follows: family socioeconomic status, family risk, school grade structure (whether seventh graders were located in the same school as high school students), and the distance (in miles) of the community in which the school was located to the nearest city of 50,000 people or more. Data used to match schools were collected through public records and a prospective telephone survey of randomly selected parents of children projected to be eligible for the study (data were then aggregated to the school level). The 3 schools within each matched set were generally homogeneous with respect to family socioeconomic status and family risk; they were randomly assigned to each of the three experimental conditions.

Four leaflets mailed to families in the control condition were titled “Living With Your Teenager.” Each leaflet was two pages long and summarized developmental research in lay language. The leaflets addressed the topics of understanding teens' emotional changes, the changing parent–child relationship, teen-related changes in thinking, and physical changes in teens. Following school matching and random assignment, schools were contacted and informed of the experimental condition to which they had been assigned.

Through the process of implementing consent procedures, all seventh grade students in participating schools and their parents were informed about the assessment procedures, and both parents and students were provided opportunities to decline the students' participation. A total of 1,650 of 1,831 eligible1 students in the 36 schools completed pretesting in the fall semester (541 LST + SFP 10–14 group students, 618 LST group students, and 491 control group students). Most of the students who did not complete the pretest assessments were absent from school when the assessments were conducted. The LST and SFP 10–14 intervention programs were both delivered during spring semester. Following delivery of the two interventions, posttest assessments were conducted with 1,5512 students (94% of those pretested), including 510 LST + SFP 10–14 students, 580 LST students, and 461 control group students. Follow-up assessments were conducted in the spring semesters of the eighth and ninth grades. At the eighth grade follow-up, approximately 1 year following the posttest and 1.5 years past baseline, 1,361 students were assessed (82% of those pretested), including 447 LST + SFP 10–14 students, 500 LST students, and 414 control group students. At the ninth grade follow-up, 1,198 students (73% of those pretested) participated in the assessment, including 399 LST + SFP 10–14 students, 430 LST students, and 369 control group students. On average, 46 students in each school completed the pretest. Slightly over half of the students were male (53%), and most participants were Caucasian (96%).

After pretesting, families of intervention group seventh graders in the LST + SFP 10–14 schools were invited to participate in the SFP 10–14 program. Intervention group families participating in in-depth, in-home family interviews3 were actively recruited for the SFP 10–14 program. Intervention group families who were not selected for or who declined the in-home interview were invited to enroll in the SFP 10–14 intervention (general announcements were made at schools) but were not actively recruited by project staff.4 Of the 228 families participating in the in-home interview in the LST + SFP 10–14 condition, 129 (61%) attended at least one SFP 10–14 program session, and 115 (88%) of these families attended four or more sessions. Ninety (69%) of the families attending at least one session also attended at least one booster session held during the spring semester of the eighth grade, and 80 (62%) attended all four booster sessions. As concerns the LST program, all the seventh graders with parental permission in the intervention schools (62 children did not obtain parental permission) were exposed to the program.

Procedures

The in-school data collection was conducted in classrooms. Approximately 40–45 min were required to complete the questionnaires. Typically, there were three to four project interviewers in each classroom to coordinate data collection. Students were assured that their responses to the questionnaires would be kept confidential. Two forms of the questionnaires were administered in each classroom to enhance the privacy of the respondents. Identical questions were asked in each form; only the order of questions was varied. In addition, each student exhaled into a balloon, which was then connected to a carbon monoxide meter to provide a carbon monoxide reading. The primary purpose of this procedure was to serve as a bogus pipeline, to encourage honesty in answering the smoking-related question. The same data collection procedures were used across all data collection points.

Multicomponent Intervention

The two empirically supported preventive interventions that were combined to form the multicomponent intervention were both designed to enhance research-based protective factors and to reduce risk factors. These programs are described below.

SFP 10–14

The SFP 10–14 (Molgaard, Kumpfer, & Fleming, 1997) is based on the biopsychosocial model (DeMarsh & Kumpfer, 1986) and other empirically based family risk and protective factor models (Kumpfer, Molgaard, & Spoth, 1996; Molgaard, Spoth, & Redmond, 2000). The seven SFP 10–14 program sessions were conducted once each week for 7 consecutive weeks when the youth were in the second semester of seventh grade. Each session included a separate, concurrent 1-hr parent and youth skills-building curriculum, followed by a 1-hr conjoint family curriculum, during which parents and youth practiced skills learned in their separate sessions. SFP 10–14 program sessions were offered in the participating schools during the evening.

Youth, parent, and family sessions used discussions, skill-building activities, videotapes that modeled positive behavior, and games designed to build skills and strengthen positive interactions among family members. In particular, the individual youth sessions focused on strengthening future goals, dealing with stress and strong emotions, increasing the desire to be responsible, and building skills to appropriately respond to peer pressure. The majority of each youth session was spent in facilitated group discussions, skill practice, and social bonding activities. Two of the youth sessions used videotapes to support the acquisition of peer pressure resistance skills and to teach specific steps in resistance.

Topics covered in parent sessions included discussing social influences on youth, understanding developmental characteristics of youth, providing nurturant support, dealing effectively with youth in everyday interactions, setting appropriate limits and following through with reasonable and respectful consequences, and communicating beliefs and expectations regarding substance use.

During the conjoint family sessions, parents and youth practiced skills learned in the separate sessions. For example, parents and youth practiced respectful listening and communicating. Emphasis was placed on the use of family meetings to teach responsibility, solve problems, and plan fun family activities. Activities included communication exercises and poster-making activities in which family members gave visual expression to program concepts. Teaching games were used to assist parents and youth in empathizing with each other and in learning skills for problem solving. Two of the family sessions made use of instructional videotapes demonstrating how to effect positive family change and maintain program benefits by holding regular family meetings.

A total of 129 families attended the SFP 10–14 in 22 groups in the 12 schools assigned to the condition. Typically, sessions were held in school buildings in the evenings. Of the 129 families in attendance, 88% attended at least four of the seven sessions, and 63% attended at least six sessions. The group sizes ranged from 3 to 15 families, with an average group size of 8 families and an average of 20 individuals per session. One hundred nineteen families represented were two-parent households, and, of those households, 83% had both parents in attendance at one or more of the sessions.

We observed each team of facilitators two or three times to assess their adherence to the intervention protocol. These observations evaluated adherence to all of the key program content and activities. Coverage of the component tasks or activities described in the group leaders' manual showed an average coverage of 98% in the family sessions, 92% in the parent sessions, and 94% in the youth sessions. We conducted reliability checks on approximately 40% of the family session observations, 21% of the parent session observations, and 14% of the youth session observations. There was a high level of interobserver agreement; observers' assessment of coverage of detailed group activities only varied by an average of 2.4% across the three types of program sessions.

Families were invited to participate in four booster sessions while the youth were in the eighth grade. As in the first set of sessions, the emphasis of the booster sessions was on enhancing protective factors for substance use and other problem behaviors and on the reduction of risk factors. The booster sessions were held approximately 1 year after the initial SFP 10–14 sessions were completed. Observer-based adherence assessments indicated that coverage of the component tasks and activities averaged 98% for the family sessions, 92% for the parent sessions, and 94% for the youth sessions. Reliability checks were conducted on 40% of the family sessions, 28% of the parent sessions, and 15% of the youth sessions. Observers' assessments varied by an average of 3% across the three types of sessions.

LST

LST (Botvin, 1996, 2000) is a universal preventive intervention program based on social learning theory (Bandura, 1977) and problem behavior theory (Jessor & Jessor, 1977). The primary goals of LST are to promote skills development (e.g., social resistance, self-management, and general social skills) and to provide a knowledge base concerning the avoidance of substance use. Students are trained in the various LST skills through the use of interactive teaching techniques, including coaching, facilitating, role modeling, feedback, and reinforcement, plus homework exercises and out-of-class behavioral rehearsal.

The teaching and skill development are accomplished through five curriculum components (Botvin, Baker, Renick, Filazzola, & Botvin, 1984). The cognitive component is designed to present information concerning the immediate and longer term consequences of substance use, current adolescent and adult prevalence rates of substance use, social acceptability of substance use, the process of becoming a user, development of substance use addiction, and media influences on behavior. Specific content is contained in four sessions on substance use information and one session on media influences.

The self-improvement component, contained in one session, includes a discussion of the formation of self-image and how self-image affects behavior as well as a self-improvement project. The two sessions on the topic of decision making contain material concerning everyday decision making, a general strategy for decision making, social pressures influencing decision making, and how to recognize persuasive strategies. The two sessions on coping with anxiety contain material designed to teach students to recognize anxiety-inducing situations that can occur in everyday life and to demonstrate and rehearse strategies to cope with anxiety. Finally, the social skills training component includes material on both verbal and nonverbal communication, strategies to prevent misunderstandings, the importance of asking questions, how to get over being shy, compliments, boy–girl relationships, verbal and nonverbal assertive skills, and resistance of peer pressure to use substances. The component includes one session on communication, two sessions on social skills, and two sessions on assertiveness.

The 15-session program was conducted during 40- to 45-min classroom periods when students were in seventh grade. Depending on individual classroom schedules, sessions were offered through a variety of scheduling formats, ranging from once per week for 15 consecutive weeks to 5 days per week for 3 consecutive weeks.

A member of the project staff observed each classroom teacher on two or three occasions while the LST program was being taught. A total of 78 single LST teacher observations and 20 double LST teacher observations were completed. Double observations were used to assess observer interrater reliability. The observers agreed in their rating of 78% of all of the individual content items covered in the curriculum. The mean observer rating for all single teacher classroom observations was 85% adherence to the instructional content.

Students also participated in five LST booster sessions when they were in eighth grade. As in the 1st year, the overall thrust of the booster sessions was to promote skills development, primarily in social resistance skills, self-management skills, and generic social skills. The booster sessions were held approximately 1 year after the seventh grade LST program was completed. Each classroom teacher was observed on one or two occasions while the LST booster program was being taught. Fifty-three single observations of implementation fidelity were completed; eight double observations were completed. The observers agreed in their ratings of 71% of the curriculum items. The mean observer rating of all LST teacher observations was 82% adherence.

Measures

Self-reported use of substances was obtained from the classroom-administered questionnaire described in the procedures section.

Substance initiation

As an extension of the earlier study when the students were in the eighth grade, the current investigation uses the substance initiation index from the earlier study's in-school assessment.

The SII (Spoth, Redmond, et al., 2002) consists of three items: (a) “Have you ever had a drink of alcohol?” (b) “Have you ever smoked a cigarette?” and (c) “Have you ever smoked marijuana (grass, pot) or hashish (hash)?” All three items were answered according to a yes–no format and coded as 1 for yes and 0 for no.

Inconsistent reports in lifetime substance use were corrected. In cases where a student reported a lifetime use behavior at one data collection point but reported no such use at a later collection point, the later report was corrected to reflect the previously reported initiation of that behavior. The three lifetime use items were summed to form the SII. Reliability (Kuder–Richardson 20) for the SII at the follow-up assessment 2.5 years past baseline was .58, and the average test–retest reliability across four measurement periods was .75.5 Prior studies have reported the use of similar substance use indices (Spoth, Redmond, & Lepper, 1999; Trudeau, Spoth, Lillehoj, Redmond, & Wickrama, 2003) and are based on the validity of such measures (e.g., Botvin et al., 1995; Elliott, Ageton, Huizinga, Knowles, & Canter, 1983; Williams et al., 1995).

Regular alcohol use

The Regular Alcohol Use (RAU) measure was a single questionnaire item asking, “About how often (if ever) do you drink beer, wine, wine coolers, or liquor (more than just a few sips)?” The item was dichotomized so that 1 indicated use of alcohol one or more times a month and 0 indicated less frequent or no use.

Weekly drunkenness

Weekly drunkenness was obtained from a single item asking, “About how often (if ever) do you drink until you get drunk?” The item was dichotomized so that 1 indicated drunkenness one or more times per week and 0 indicated a frequency of drunkenness lower than once a week.

Analyses

Individual scores on the SII were examined via a multilevel analysis of covariance (hierarchical linear modeling via SAS PROC MIXED, with restricted maximum likelihood estimation), with school included as a random factor (students were nested within schools). Because assignment to the intervention conditions was by block at the school level, analyses were conducted on the basis of a randomized block design. Pretest scores and the pretest proportion of dual biological parent families (aggregated to the school level) were included as covariates in all outcome analyses.6 To test measures with reasonably normal distributions, we aggregated the dichotomous outcome measures (RAU, weekly drunkenness) to the school level prior to analysis. We conducted repeated measures growth curve analyses for all study variables to test for slope differences among study conditions across time. Because positive intervention effects were hypothesized, on the basis of earlier outcome studies, all tests of significance were one-tailed.

Results

Pretest Equivalence

Pretest equivalence of the sample on sociodemographic and outcome measures was assessed. No significant condition differences were found for any of the outcome measures. Despite the school matching procedures and the confirmation of the homogeneity of the blocks from which schools were assigned, there was evidence of inequivalence on one of the sociodemographic factors, namely, the proportion of dual biological parents. The control group appeared to be at a lower level of risk (i.e., it showed a greater proportion of dual-parent families than the two intervention groups) at the time the study was initiated. As described above, this variable was included as a control variable in the subsequent outcome analyses.

Differential Attrition

We conducted analyses to rule out differential attrition by examining Condition × Dropout Status interactions with the outcome variables at the posttest and at the two follow-up assessments. No significant Dropout × Condition interactions were found. In general, however, those who remained in the study tended to score lower on the outcome measures than those who had dropped out.

Effects on Long-Term Substance Initiation, Regular Alcohol Use, and Drunkenness

Growth curve analyses tested for slope differences among the conditions over time and provided for planned contrasts of the adjusted mean scores among the conditions at the follow-up 2.5 years past baseline. These results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Substance Initiation Index (SII), Regular Alcohol Use (RAU), and Weekly Drunkenness (WD): Adjusted Means at Follow-Up and Tests of Growth Trajectories

| Adjusted means |

Tests of differences (t values) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 |

T2 |

C |

Point in time |

Growth trajectories |

|||||||

| Outcome | M | SE | M | SE | M | SE | T1 vs. C | T2 vs. C | T1 vs. C | T2 vs. C | T1 vs. T2 |

| SII | 1.445 | 0.043 | 1.426 | 0.043 | 1.524 | 0.047 | 1.24 | 1.57† | 1.09 | 2.67** | 1.68* (T2) |

| RAU | 0.229 | 0.025 | 0.198 | 0.025 | 0.240 | 0.026 | 0.30 | 1.16 | 0.37 | 1.35† | 0.95 |

| WD | 0.038 | 0.011 | 0.034 | 0.010 | 0.056 | 0.011 | 1.44† | 1.87* | 1.51† | 1.38† | 0.06 |

Note. Adjusted means are from the analysis of covariance. Follow-up took place 2.5 years past baseline. T1 = Life Skills Training only; T2 = Life Skills Training plus Strengthening Families Program: For Parents and Youth 10–14; C = minimal contact control.

p ≤ .10.

p ≤ .05.

p < .01. All tests are one-tailed.

Substance initiation

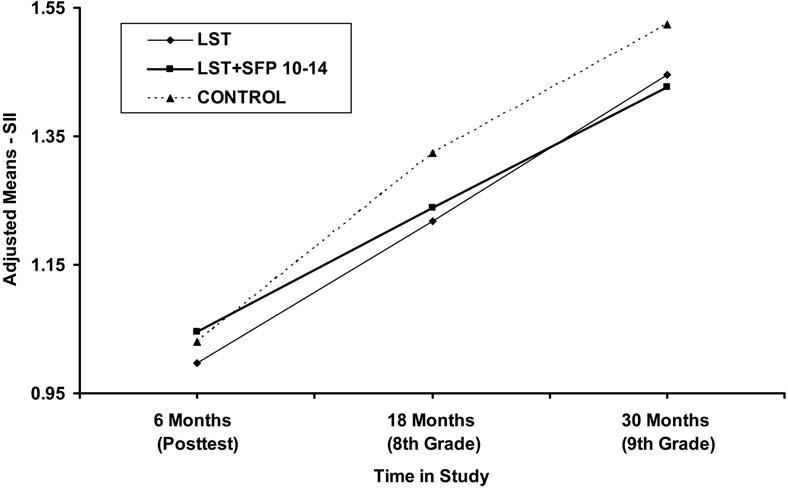

Growth of the SII for the LST + SFP 10–14 condition was significantly slower than that for both the control group, t(1, 4049) = 2.67, p < .01, and the LST-only group, t(1, 4049) = 1.68, p < .05. In addition, at the 2.5 years past baseline data collection point, the difference in the adjusted mean SII score between the LST + SFP 10–14 and control groups approached significance, t(1, 4049) = 1.57, p = .06. A significant difference in rate between the LST-only condition and the control group was not found for this variable.7 The adjusted means for the SII across waves of data collection are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Adjusted means for the Substance Initiation Index (SII) across waves of data collection by experimental condition. LST = Life Skills Training; SFP 10–14 = Strengthening Families Program: For Parents and Youth 10–14.

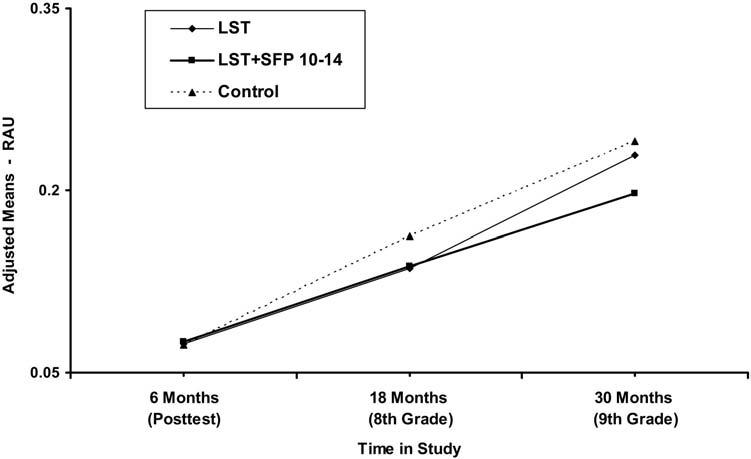

Regular alcohol use

There were no statistically significant intervention effects found for regular alcohol use. The LST + SFP 10–14 group increased at a slower rate than the control group on the RAU measure; this difference only approached statistical significance, t(1, 65) = 1.35, p < .10. Adjusted means for the RAU measure across waves of data collection are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Adjusted means for the Regular Alcohol Use (RAU) measure across waves of data collection by experimental condition. LST = Life Skills Training; SFP 10–14 = Strengthening Families Program: For Parents and Youth 10–14.

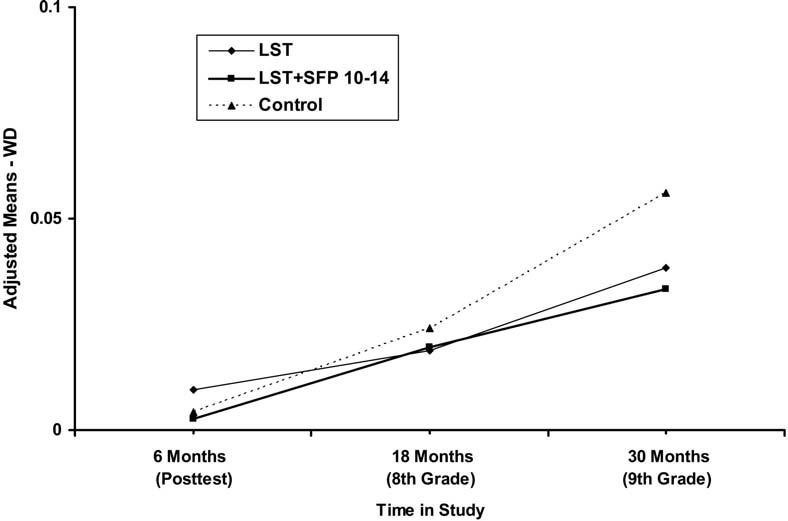

Weekly drunkenness

Adjusted means scores on weekly drunkenness for the LST + SFP 10–14 condition were found to be significantly different from the control condition at the follow-up assessment 2.5 years past baseline, t(1, 65) = 1.87, p = .03. The LST-only adjusted mean also was lower than that for controls, but the difference was only marginally significant, t(1, 65) = 1.44, p = .08. The observed rates of growth of weekly drunkenness for both intervention conditions were found to be lower than that of the control condition but, again, only approached statistical significance: t(1, 65) = 1.51, p = .07, for the LST-only condition, and t(1, 65) = 1.38, p = .09, for LST + SFP 10–14. The adjusted means for the weekly drunkenness measure across waves of data collection are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Adjusted means for weekly drunkenness (WD) across waves of data collection by experimental condition. LST = Life Skills Training; SFP 10–14 = Strengthening Families Program: For Parents and Youth 10–14.

Discussion

Overall, the pattern of findings from the present study is consistent with a developmental progression of positive outcomes. That is, there were slower rates of growth in substance use among those in the intervention conditions. Also, the most problematic type of use measured, weekly drunkenness, showed a point-in-time difference for the combined intervention at the last wave of data collection, plus growth that was relatively slower but that was not in the statistically significant range.

The practical implications of these findings can be conveyed through a description of comparative percentages of use in the intervention and control conditions associated with the reported differences between conditions. For example, although weekly drunkenness is sufficiently extreme for students that it is observed fairly infrequently, a relative reduction rate of 39% for weekly drunkenness in the LST + SFP 10–14 condition means that the rate of weekly drunkenness in the LST + SFP 10–14 group was 39% lower than that in the control group at the 2.5-year assessment. Such a relative reduction rate suggests that for every 100 normal or general population adolescents reporting drunkenness on a weekly basis, only 61 intervention group adolescents will likely do so over the same period.

The strongest growth-related effect for the multicomponent intervention (LST + SFP 10–14) was evident on the SII, following a typical pattern of longitudinal results. That is, longitudinal studies of preventive interventions are expected to first show and sustain an impact on initiation, with impact on more problematic types of use emerging through the junior high school years. This is the case because typical developmental progression of substance use in young adolescence begins with initiation and progresses to more frequent or more problematic use (Botvin et al., 2001; Spoth et al., 1999). Such a developmental progression corresponds to observed increases in student population prevalence rates of substance use in the early high school years, with initiation increasing to very high prevalence rates by the time students reach the 12th grade. In the case of alcohol, appreciable rates of regular and more problematic types of use typically emerge in middle school or junior high school (Botvin et al., 2001).

The multilevel growth analyses showing that students in the multicomponent intervention condition (LST + SFP 10–14) demonstrated slower rates of growth in substance initiation approximately 2.5 years after the pretest are worthy of further note. Positive findings at the earlier follow-up on the SII (Spoth, Redmond, et al., 2002), when considered with the current findings, suggest a continuance of the earlier pattern of results. That is, as expected, the multicomponent intervention generally showed stronger results in intervention–control comparisons than did the control comparisons with LST only. When they were compared directly, the multicomponent intervention condition demonstrated a significantly slower rate of increase in initiation than the LST-only condition, as indicated in Table 1. Although the LST-only versus control comparison indicated that the LST-only condition showed slower growth than did the control condition, it did not attain a conventional level of statistical significance. In the prior study of an earlier version of the SFP 10–14 intervention, an increasing effect of the intervention was observed over time, with widening intervention–control differences over a period of 4 years and a pattern of delayed progression over a 6-year period (Spoth et al., 2004). Taken together, earlier and current findings suggest that the combination of SFP 10–14 with LST likely contributes meaningfully to long-term effects observed on substance initiation.

The positive results on weekly drunkenness are especially noteworthy. That is, the LST + SFP 10–14 group showed significantly lower levels of weekly drunkenness at the assessment 2.5 years past baseline than did the control group. The LST + SFP 10–14 versus control comparison on growth in weekly drunkenness approached significance. The LST-only point-in-time and growth comparisons with the control condition also showed favorable intervention differences, although without attaining statistical significance at the .05 level, following a pattern similar to other outcomes. Again, the relatively weaker LST effect may well be attributable to the enhanced benefits of adding the family-focused intervention component.

The mixed findings evident within a pattern of statistically significant outcomes and generally positive trends in the results warrant careful consideration. Most notable is that there were no positive outcomes for the multicomponent intervention on the measure of regular alcohol use. Also, although effects at the .10 level were observed for each of the outcomes and most consistently for the combined LST + SFP 10–14 intervention, the number of intervention–control comparisons showing lower magnitude effects highlights the need to attend to a number of factors in the interpretation of the mixed findings.

Our earlier studies (Spoth et al., 2001; Spoth et al., 2004) of family-focused interventions have generally shown more consistently positive, higher magnitude results following posttest evaluations. In combination, two major differences between the earlier and present studies likely contributed to relatively more mixed and lower magnitude results in the current study. The first is that the family-focused intervention typically has been implemented when students are in the sixth grade rather than in the seventh grade, as it was in this study. Indeed, in a number of earlier reports, we have emphasized the importance of the developmental timing of family-focused interventions. The timing appears to be best when students are in the early stage of exposure to and experimentation with substance use; in this rural midwestern sample of students, this typically occurs in the sixth grade. This is a point at which use by only a small percentage of students is associated with lower levels of peer influence toward use on average, as discussed in more detail below.

The reason for the later implementation in the present case is that the family-focused intervention was offered in combination with the LST school-based intervention, which is typically implemented in seventh grade. In retrospect, it appears that it would have been better either to implement the school-based LST component earlier, rather than implement the family-focused component later, or to offer the interventions sequentially. This latter approach was the tactic chosen in a new study now underway. The second major dissimilarity between the present and earlier studies concerns differences between the intervention and control conditions at baseline that might have favored a slower rate of growth in substance use in the control group, thus rendering it more difficult to detect intervention–control differences. The higher proportion of families with two biological parents in the control group was noted earlier; we subsequently discuss possible substance use growth effects of the lower baseline rates of substance use in the control group.

Data from another study of the earlier version of the SFP 10–14 (Spoth et al., 2001) suggested a positive diffusion effect of well-timed preventive interventions. Such an effect concerns the compounding of small intervention-generated changes in early substance use initiation rates. In particular, to the extent that a preventive intervention is successful in delaying substance onset among a small number of early initiators, the resulting decreases in peer influences will accumulate, slowing group-level growth in initiation for a substantial period of time following intervention. In the case of a controlled study conducted with stable, intact groups as the unit of assignment, this effect would result in intervention–control differences that would be expected to increase over a number of years following intervention before intervention effects would begin to decay (Redmond, Shin, & Spoth, 2003). That postulated effect mechanism may help to explain the pattern of initiation findings in the current study, particularly when considered in conjunction with the literature on the developmental progression and epidemiology of substance use.

Another salient feature of the hypothesized positive diffusion effect mechanism is its sensitivity to early rates of substance use (Redmond et al., 2003). Small and statistically nonsignificant increases in early-stage use rates can produce long-term compounding increases in those rates over time. This effect may help explain the effects of the interventions on regular alcohol use and the drunkenness initiation measure; for example, at posttesting, unadjusted control group rates for regular alcohol use and initiation of drunkenness were 4% for both measures, whereas corresponding rates for the LST-only group were 8% and 10%. For the LST + SFP 10–14 group, they were 8% and 12%, respectively, at that point in time. The effects of these differences would tend to increase the subsequent rates of growth in the intervention groups relative to the control group, making it more difficult to detect intervention effects.

The reader should remain cognizant of the limitations of this study. In particular, this study was conducted in small communities in a rural midwestern state. Characteristic of the study region, the sample population was predominantly White. It is noteworthy, however, that earlier research has addressed this generalizability issue. The school-based intervention, LST, has been proven effective in reducing serious drinking among minority (primarily African American and Hispanic), inner city middle-school students over time (Botvin et al., 2001). Concerning the family-focused SFP 10–14, researchers have suggested that when intervention program content, delivery, and implementation are culturally adapted, positive outcomes can be expected to be somewhat similar to those in majority populations (Kumpfer, Alvarado, Smith, & Bellamy, 2002). Indeed, a recent study with a randomly selected subsample of African American families used an adaptation of the family-based SFP 10–14 and focused primarily on modifying the presentation of the intervention. It showed high levels of participation and attendance (Spoth, Guyll, Chao, & Molgaard, 2003). Pilot outcome evaluation in this pilot study showed mixed results. Nonetheless, applications of pilot study findings to a randomized, controlled study of an intervention adaptation with more culturally specific content are demonstrating positive outcomes at posttesting (Brody et al., 2004).

In closing, it is worth noting the potential public health benefits of preventive interventions that address the high prevalence of substance use among adolescents. Especially noteworthy are the possible benefits of reductions in costly disorders and problematic use of substances among young adults. Such benefits have been shown to be associated with delayed initiation and progression of substance use (e.g., Grant & Dawson, 1997; Spoth, Guyll, & Day, 2002; Spoth et al., 2001). The positive trends and point-in-time outcomes on weekly drunkenness should be highlighted in that context; recent findings support the conclusion that frequent drunkenness is a relatively stronger indicator of the type of problem drinking that has clear adverse health and social consequences (Bailey, 1999; Midanik, 1999, 2003). Public health benefits can be realized if large numbers of the general population are engaged in brief interventions that are readily implemented via existing intervention delivery systems (Spoth et al., 2004). This study provides positive results of a theory-based, multicomponent, universal intervention on the initiation of substance use and suggestive results on the progression of alcohol use, in the form of problematic weekly drunkenness. Nonetheless, it is important to follow up with the current sample to show more clearly demonstrated, longer term positive effects, ones that should be in evidence if the currently observed positive outcome trends continue.

Footnotes

Work on this article was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse Research Grant DA 010815.

In fact, a total of 1,677 students completed the pretest assessment. Initially, 4 cases were lost because they lacked identification numbers. Subsequently, some students moved from a school in one condition to a school in another condition, resulting in a loss of 9 cases (as reported earlier). Inspection of the data, including the wave collected 2.5 years past baseline, found additional inconsistencies in reporting (e.g., a student's family identification number indicated that the student was in one experimental condition and the same student's school identification number indicated that the student was in a different condition), resulting in a loss of 14 cases. Because these students could not be assigned to one of the experimental conditions, their data are not counted in this sample summary, resulting in a count of 1,650 students assessed at pretest.

Posttest assessments were completed by a total of 1,690 seventh graders, eighth grade follow-up assessments were completed by at total of 1,633 students, and ninth grade follow-up assessments were completed by a total of 1,624 students. Analyses were limited to those who were among the 1,650 pretested students whose experimental condition was consistent across all waves of data provided.

In-home family pretest interviews were conducted with 691 randomly selected families of the seventh graders in the 36 study communities (most seventh graders participating in the in-home interviews also participated in the in-school survey). These interviews included written questionnaires completed by parents and the seventh grade child as well as videotaped family interactions. Follow-up interviews were repeated in the spring of the seventh, eighth, and ninth grades. Although the primary purpose of the in-home interviews was to assess family characteristics and dynamics, the child questionnaires also included items addressing substance use. These items included items similar to—though not generally identical to—the items from the in-school survey used in the current study. An examination of nonidentical but parallel items from the in-home and in-school questionnaires conducted by Azevedo, Redmond, Lillehoj, and Spoth (2003) suggests that students may tend to underreport levels of substance use during interviews conducted in their home (despite the presence of an interviewer to protect confidentiality); it was not unusual for reporting level differences at pretesting to be more than 50% lower for data collected in the home (reporting differences tended to decline over time but remained substantial at the ninth grade assessment). These findings, in conjunction with the smaller in-home sample size, led us to focus on the data collected through the in-school surveys for this study. In the context of addressing setting effects on self-reports (Azevedo et al., 2003), we conducted analyses parallel to those reported in the current study using measures constructed from the in-home data. The overall pattern of findings was similar to findings from analysis of the in-school data (comparisons favored the intervention groups) but weaker, likely owing to smaller condition differences associated with lower use rates that were possibly a product of underreporting; statistically significant findings were found for the Substance Initiation Index (SII) only. Work continues toward definitive conclusions about setting effects, though that goal is rendered more difficult by nonidentical measures and confounds.

A prospective survey of families in participating school districts provided data demonstrating that the 228 families in the in-home interview were representative (Spoth, Redmond, & Shin, 2000). Thus, recruitment from that subsample was not expected to introduce bias to a greater degree than would be the case if all 541 families of the seventh grade students had been more actively recruited. For this reason, the savings accrued from (a) more focused and active recruitment limited to families participating in the pretest in-home assessment and (b) collection of data from an in-home interview sample that was smaller—but included outcome data from a higher proportion of families exposed to the intervention—was considered to be the better option.

The predictive validity of the SII measure has been assessed with data from a separate longitudinal study on a similar population of adolescents. In that study, the SII measure was demonstrated to be significantly and positively associated with past-month cigarette smoking, past-month alcohol use, past-month marijuana use, and aggressive– hostile behaviors assessed across the 7th to 10th grades.

With four data collection points, the primary emphasis of our study is the test of differences (intervention vs. control) in the linear rates of change in substance use outcomes over time. Thus, pretest is used as a covariate. For consistency in reporting results, we show the adjusted means and point-in-time comparisons using both pretest and the presence of dual biological parents (the proportion of such families in the school) as covariates. All analyses either are multilevel, adjusting for the nature of the nested data (students in schools), or were conducted with variables aggregated to the school level.

Because of the present study's focus on alcohol as the drug of choice among the students in the study, we conducted supplemental analyses to assess outcomes on two alcohol-related initiation measures at the single-item level: namely, alcohol initiation and the initiation of drunkenness. There were no significant differences in the adjusted mean scores on either of the two item-level alcohol initiation measures at the .05 level, for either intervention condition. However, we observed differences at the .10 level for the item-level drunkenness initiation measure. That is, there was a difference between the LST-only and control conditions, for both the point-in-time test, t(1, 65) = 1.44, p = .07, and the growth trajectory, t(1, 65) = 1.56, p = .06.

References

- Ackerman S, Zuroff DC, Moskowitz DS. Generativity in midlife and young adults: Links to agency, communion, and subjective well-being. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2000;50:17–41. doi: 10.2190/9F51-LR6T-JHRJ-2QW6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony J. Selected issued pertinent to epidemiology of adolescent drug use and dependence; Paper presented at the meeting of the Annenberg Commission on Adolescent Substance Abuse; Philadelphia. Aug, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo K, Redmond C, Lillehoj C, Spoth RL. Contradictions across in-school and in-home reports of adolescent substance use initiation; Poster presented at the meeting of the Society for Prevention Research; Washington, DC. Jun, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey SL. The measurement of problem drinking in young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60:234–244. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social learning theory. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A, Metzler C. A public health perspective for research on family-focused interventions. In: Ashery R, Robertson E, Kumpfer K, editors. NIDA research monograph on drug abuse prevention through family interventions. National Institute on Drug Abuse; Rockville, MD: 1999. pp. 430–458. [Google Scholar]

- Botvin GJ. Life skills training: Promoting heath and personal development. Princeton Health Press; Princeton, NJ: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Botvin GJ. Life skills training. Princeton Health Press; Princeton, NJ: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Botvin GJ, Baker E, Dusenbury L, Botvin EM, Diaz T. Long-term follow-up results of a randomized drug abuse prevention trial in a White middle-class population. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1995;273:1106–1112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvin GJ, Baker E, Renick NL, Filazzola AD, Botvin EM. A cognitive-behavioral approach to substance abuse prevention. Addictive Behaviors. 1984;9:137–147. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(84)90051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvin GJ, Griffin KW, Diaz T, Ifill-Williams M. Preventing binge drinking during early adolescence: One- and two-year follow-up of a school-based preventive intervention. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:360–365. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.15.4.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Murry VM, Gerrard M, Gibbons R, Molgaard V, McNair L, et al. The Strong African American Families Program: Translating research into prevention programming. Child Development. 2004;75:900–917. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB. Understanding binge drinking: Introduction to the special issue. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:283–286. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.15.4.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMarsh J, Kumpfer KL. Family-oriented interventions for the prevention of chemical dependency in children and adolescents. Prevention. 1986;18:117–151. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan SC, Strycker LA, Duncan TE. Exploring associations in developmental trends of adolescent substance use and risky sexual behavior in a high-risk population. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1999;22(1):21–34. doi: 10.1023/a:1018795417956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, Ageton SS, Huizinga D, Knowles BA, Canter RJ. The prevalence and incidence of delinquent behavior: 1976–1980. Behavioral Research Institute; Boulder, CO: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM–IV alcohol abuse and dependence: Results from the national longitudinal alcohol epidemiologic survey. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1997;9:103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood HJ, Fountain D, Livermore G. Economic costs of alcohol abuse and alcoholism. In: Galanter M, editor. Recent developments in alcoholism: Vol. 14. The consequences of alcoholism: Medical, neuropsychiatric, economic, cross-cultural. Plenum Press; New York: 1998. pp. 307–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:64–105. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson KH, Romer D. Findings and future directions. In: Romer D, editor. Reducing adolescent risk: Toward an integrated approach. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. pp. 374–378. [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Jessor SL. Problem behavior and psychosocial development: A longitudinal study of youth. Academic Press; New York: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Kaestner R. The effect of illicit drug use on the wages of young adults. Journal of Labor Economics. 1991;9:381–412. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Yamaguchi K. From beer to crack: Developmental patterns of drug involvement. American Journal of Public Health. 1993;83:851–855. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.6.851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumpfer KL, Alvarado R, Smith P, Bellamy N. Cultural sensitivity and adaptation in family-based prevention interventions. Prevention Science. 2002;3:241–246. doi: 10.1023/a:1019902902119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumpfer KL, Molgaard V, Spoth R. The Strengthening Families Program for the prevention of delinquency and drug use. In: Peters RD, McMahon RJ, editors. Preventing childhood disorders, substance abuse, and delinquency. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1996. pp. 241–267. [Google Scholar]

- Lange JE, Voas RB. Defining binge drinking quantities through resulting blood alcohol concentrations. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:310–316. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.15.4.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midanik LT. Drunkenness, feeling the effects and 5+ measures. Addiction. 1999;94:887–897. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94688711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midanik LT. Definitions of drunkenness. Substance Use & Misuse. 2003;38:1285–1303. doi: 10.1081/ja-120018485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molgaard V, Kumpfer K, Fleming B. The Strengthening Families Program: For Parents and Youth 10–14. Iowa State University Extension; Ames: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Molgaard VM, Spoth R, Redmond C. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; Washington, DC: 2000. Competency training: The Strengthening Families Program for Parents and Youth 10–14. OJJDP Juvenile Justice Bulletin NCJ 182208. [Google Scholar]

- Monitoring the Future (n.d.) http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/data/03data.html#2003data-drugs. Drug and alcohol press release and tables. Retrieved March 5, 2004, from.

- Mrazek PJ, Haggerty RJ, editors. Reducing risks for mental disorders: Frontiers for preventive intervention research. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redmond C, Shin C, Spoth RL. A diffusion model of substance initiation: Preventive intervention and public health implications; Poster presented at the meeting of the Society for Prevention Research; Washington, DC. Jun, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, Bauman KE, Harris KM, Jones J, et al. Protecting adolescents from harm: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;278:823–832. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Przybeck TR. Age of onset of drug use as a factor in drug and other disorders. In: Jones CL, Battjes RJ, editors. Etiology of drug abuse: Implications for prevention. National Institute on Drug Abuse; Rockville, MD: 1985. pp. 178–192. (NIDA Research Monograph No. 56). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth RL, Greenberg MT. Toward a comprehensive strategy for effective practitioner-scientist partnerships and larger-scale community benefits. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2005;35:107–126. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-3388-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Guyll M, Chao W, Molgaard V. Exploratory study of a preventive intervention with general population African American families. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2003;23:435–468. [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Guyll M, Day SX. Universal family-focused interventions in alcohol-use disorder prevention: Cost-effectiveness and cost-benefit analyses of two interventions. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:219–228. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Redmond C, Lepper H. Alcohol initiation outcomes of universal family-focused preventive interventions: One- and two-year follow-ups of a controlled study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;(Suppl 13):103–111. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1999.s13.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Redmond C, Shin C. Modeling factors influencing enrollment in family-focused preventive intervention research. Prevention Science. 2000;1:213–225. doi: 10.1023/a:1026551229118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Redmond C, Shin C. Randomized trial of brief family interventions for general populations: Adolescent substance use outcomes four years following baseline. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:627–642. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.4.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Redmond C, Shin C, Azevedo K. Brief family intervention effects on adolescent substance initiation: School-level curvilinear growth curve analyses six years following baseline. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:535–542. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Redmond C, Trudeau L, Shin C. Longitudinal substance initiation outcomes for a universal preventive intervention combining family and school programs. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2002;16:129–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Results from the 2001 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Volume I. Summary of national findings. Office of Applied Studies; Rockville, MD: 2002. (DHHS Publication No. SMA 02–3758, NHSDA Series H-17). Available on the Web at. [Google Scholar]

- Thombs DL, Olds RS, Snyder BM. Field assessment of BAC data to study late-night college drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:322–330. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trudeau L, Spoth R, Lillehoj CJ, Redmond, Wickrama KAS. Effects of a preventive intervention on adolescent substance initiation, expectancies, and refusal intention. Prevention Science. 2003;4:109–122. doi: 10.1023/a:1022926332514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams CL, Perry CL, Dudovitz B, Veblen-Mortenson S, Anstine PS, Komro KA, Toomey TL. A home-based prevention program for sixth-grade alcohol use: Results from Project Northland. Journal of Primary Prevention. 1995;16:125–147. doi: 10.1007/BF02407336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle M, Windle RC. Depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking among middle adolescents: Prospective associations and intrapersonal and interpersonal influences. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:215–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]